Martel and Biller reported that the socially ideal height for western menis 188 cm (6 ft 2 in) andrising.1 Withadvances in genetic engineering, parents will be able to control the heightsof their children, and these heights are likely to increase with each newgeneration. Indeed, greater height and associated lean body mass are viewedpositively by the medical profession and society. This bias is based on a fewstudies and our cultural values but ignores extensive data that indicate thatshorter stature is healthier. We summarize our findings of more than 25 yearsof personal and literatureresearch.

Table 1.

Age-standardized death rates from all causes, coronary heart disease(CHD), and stroke per 100,000 population (males) for 6 ethnic groups inCalifornia

| Ethnic groups* | Height, cm (in) | Age-standardized death rates/100,000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cause | CHD | Stroke | ||

| African American | 178 (70) | 1,800 | 316 | 102 |

| White | 178 (70) | 1,243 | 302 | 60 |

| Hispanic | 172 (68) | 856 | 175 | 49 |

| Asian Indian† | 170 (67) | 668 | 258 | 33 |

| Chinese | 169 (66) | 773 | 155 | 62 |

| Japanese | 169 (66) | 693 | 146 | 52 |

In order of decreasing height.

Based on height data for upper socioeconomic status in India.

HEIGHT AND HEALTH

In the past 20 years, the “bigger is better” misconception hasbeen promoted by studies that found that taller people—men over 183 cm(6 ft) and women over 165 cm (5 ft 5 in)—have lower death rates fromheart disease and all causes than shorter people (men under 170 cm [5 ft 7 in]and women under 150 cm [4 ft 11 in]). In 1999, we reviewed the findings ofseveral of thesestudies.2 Virtuallyall of these articles have ignored abundant data showing that short height perse does not adversely affect health. For example, the first National Healthand Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) found no relation between heightand heart disease when age and years of education were adjusted for 13,031 menand women tracked for 13years.3 Theinvestigators reported that previous studies on height and health sufferedfrom weaknesses and inconsistencies that compromised their findings. Morerecently, Okasha et al found no association between height and all-causemortality in a study of 10,700 male and female students at Glasgow University,Glasgow, Scotland, observed for 40years.4

The average height before the 20th century was about 10 cm (∼4 in)shorter than today. Yet, coronary heart disease (CHD) before 1900 wasrare.2 Although onlyabout 50% of the population reached 50 years of age, those surviving to 50could expect to live another 15 to 20 years. Thus, CHD was uncommon eventhough there were many elderly people in the early 1900s and earlier. Sincethe 1960s, countries like India and Singapore have seen large increases in theincidence of CHD (including in young adults) with dietary changes andincreased height.

Women average about 13 cm (∼5 in) shorter than men and haveconsiderably lower rates of CHD. Although hormones are assumed to explain thisadvantage, they may play only a partial role. For example, based on 1,700deceased people in Ohio, Miller found that men and women of the same heighthad about the same lifespan.5

FINDINGS SUGGESTING THAT SHORT STATURE IS HEALTHIER

During the second half of the 20th century, the people living the longestincluded the Japanese, Hong Kong Chinese, andGreeks2—allbeing shorter and weighing less than northern Europeans and North Americans.In addition, data from the California Department of Health indicate thatAsians and Hispanics live more than 4 years longer than tallerwhites.6 Wild andassociates found that East Indians, Chinese, Japanese, and Hispanics inCalifornia had lower all-cause and CHD death rates, as shown in theTable.7 Heightsobtained from other sources are shown for each ethnic group and indicate thatshorter ethnic groups had lower death rates.

Compared with northern Europeans, shorter southern Europeans hadsubstantially lower death rates from CHD and allcauses.2 Greeks andItalians in Australia live about 4 years longer than the taller hostpopulation, and shorter Turkish migrants in Germany have an age-adjusted CHDdeath rate half that of taller indigenous Germans. Others have pointed outthat genetics is not the primary factor here because after a few generations,Mexican and Japanese migrants approach the CHD and cancer rates of the hostcountry.2 One of us(H E) led medical teams in studies of eight populations selected for healthyand vigorous people and found that they were also smallpeople.8

A report on a 25-year study of Okinawans indicates that they have thegreatest longevity in the world, including exceeding that of mainlandJapanese.9 Okinawansare vigorous and healthy into advanced ages and continue a high level ofphysical activity into their 90s. They have the lowest rates of cancer andheart disease in the world and also exceed most countries in centenarians at arate of 34 per 100,000 versus 5 to 10 per 100,000 for industrialized nations.Bone fractures were found to be substantially less than in mainland Japan andthe United States. The Okinawans eat a low-calorie, high-fiber diet rich invegetables, grains, and soy. Monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats(especially omega 3) are consumed in preference to saturated fats. Refinedcarbohydrates and animal products, except for fish, are consumed in smallamounts. Tea and small amounts of alcohol are drunk daily. However, saltintake is 7 g, which is higher than the less than 1 g consumed by populationswith lifelong low blood pressure.

The researchers, Willcox etal,9 did notattribute this superior health to genetics because when younger Okinawansmigrate to mainland Japan, Hawaii, or the United States, they soon acquire thechronic diseases of the host population. The Okinawans are shorter and weighless than mainland Japanese, and men aged 87 to 104 years average 145.4 cm (4ft 9 in) and 42.8 kg (94lb).2

Other researchers have found many traditional societies with good healthand little CHD andcancer.10,11,12For example, Walker found that rural blacks in South Africa had virtually noCHD and little diet-relatedcancer.2,10The blacks averaged about 10 cm shorter than whites. Lindeberg etal11 reported thatMelanesians living in Kitava were healthy and that heart disease and strokewere virtually absent in a population ranging in age from 20 to 86 years. Themen averaged 161 cm (5 ft 3 in) and 53 kg (117 lb). A study of Solomon Islandpopulations also found them to be free of CHD and healthy, with male heightsranging from 160 to 163cm.12

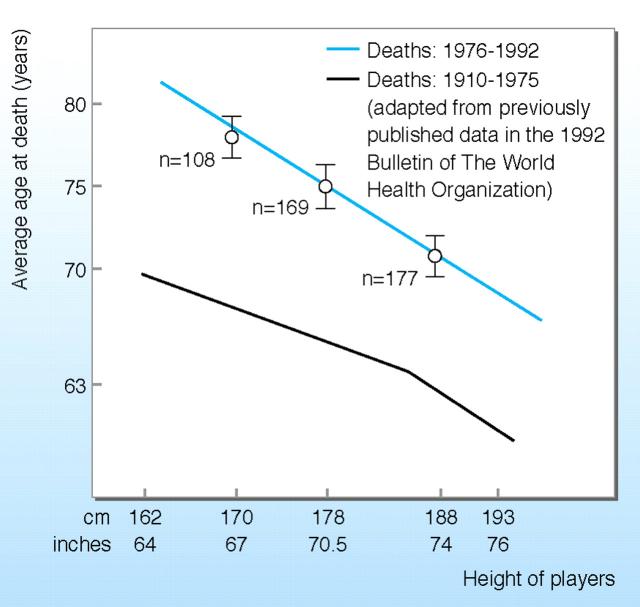

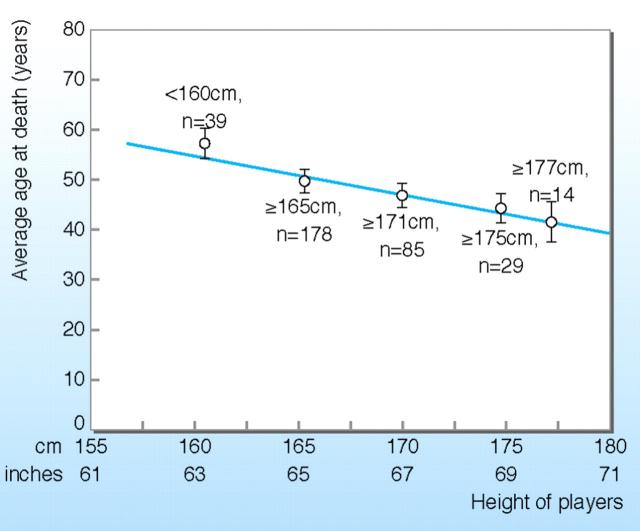

Longevity studies of deceased US veterans found an inverse relation betweenheight andlongevity.13Evaluation of height and longevity of deceased professional base-ball playersand 19th century French men and women also showed an inverse relation, asshown in figures 1 and2.14In a review of literature on height, body size, and longevity, we foundseveral studies that showed a negative correlation between height andlongevity.2

Figure 1.

Reduction of baseball players' average life span with increasing height.(Reproduced with permission of Washington Academy of Sciences, Washington,DC.)

Figure 2.

Average life span in years versus height for 19th century deceased Frenchmen. (Reproduced with permission of Washington Academy of Sciences,Washington, DC.)

Many studies have found a positive correlation between cancer, rapidgrowth, and height.2For example, Albanes reported that rapid growth during adolescence is tied toincreased cancer risk in adulthood, with a 3- to 4-mm increment in leg lengthabove average resulting in an 80% higher risk in nonsmoking-related cancer,based on a 50-yearfollow-up.15 Hebertet al also found that taller US physicians (183 cm [6 ft] or more) had ahigher cancer rate than shorter ones (170 cm [5 ft 7 in] ormore).16

DATA FROM ANIMAL STUDIES

Among different species, larger species usually grow and mature slower andlive longer. However, studies of animals within the same species provideopposite results. Since the 1930s, experimental studies of genetically similaranimals have found that caloric restriction with adequate nutrition producessmaller animals with extendedlongevity.2 Bartkealso conducted studies with genetically small mice and found that small sizewith ad lib nutrition resulted in extendedlongevity.17 Hereported that body size was a major determinant of longevity. Rollo et alfound that genetically large mice had reduced longevity compared withnormal-sizedmice.18 They alsofound that larger animals within the same species have rapid growth, higherreproductive effort, and accelerated aging.

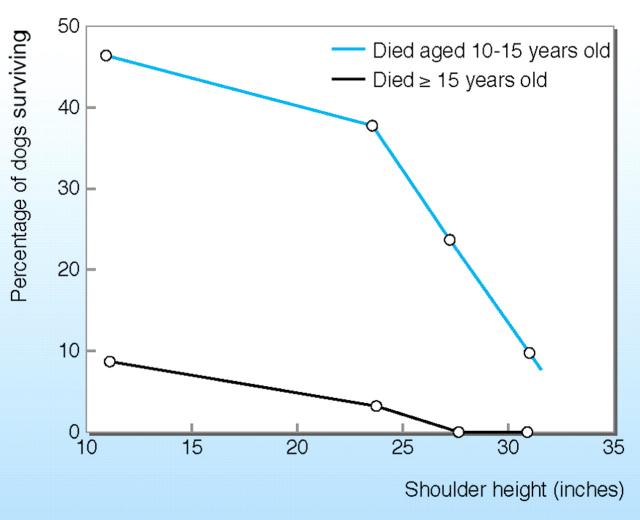

Bartke reported that a negative correlation between body size and longevityapplies to mice, dogs, and probablyhumans.17 Largeamounts of data are available on dogs, and researchers have found that smallerdogs live longer than largerdogs.19Figure3 shows the survival of dogs based on height. Studies of monkeyshave been under way for more than 10 years, and thus far the findings supportthose of longevity studies of smaller calorie-restricted mice and otherspecies.2,17We described human examples of the benefits of caloric restrictionelsewhere.2

Figure 3.

Longevity of dogs for 4 height groups: short, medium, tall, and verytall

BIOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

The biologic reasons for the lower longevity of larger bodies include morecells subject to carcinogens and the using up of cell-doubling potential(∼50 doublings maximum) to achieve larger body size as an adult. Thissubject was discussedpreviously,2 andmore detail is provided in a secondarticle.20

CONCLUSION

Rapid developments in genetic engineering are likely to lead to substantialincreases in the height of future generations. Health and longevity arestrongly affected by socioeconomic status, relative weight, regular exercise,and various health practices. However, animal and human data suggest thatlarger body size independently reduces longevity. Therefore, the promotion ofgreater height and lean body mass in our children needs to be objectivelyevaluated by the medical profession before it becomes the norm.

Competing interests: None declared

- Advances in genetic engineering will promote a continual increase in heightof successive generations

- International and national studies have shown that tallness has health andlongevity risks

- Body size is controllable through dietary practices, especially duringchildhood and adolescence

- Many studies indicate that a near-vegetarian diet with high fiber, lowsalt, and few processed foods promotes health and greater longevity

- Extensive data from animal studies indicate that people with smaller bodieshave delayed onset of chronic diseases and greater longevity

References

- 1.Martel LF, Biller HB. Stature and Stigma.Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1987.

- 2.Samaras TT, Elrick H. Height, body size and longevity.Acta Med Okayama 1999;53:149-169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao Y, McGee DL, Cao G, Cooper RS. Short stature and risk ofmortality and cardiovascular disease: negative findings from the NHANES Iepidemiologic follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:678-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okasha M, McCarron P, McEwen J, Davey Smith G. Height and cancermortality: results from the Glasgow University student cohort.Public Health 2000;114:451-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller DD. Economics of scale. Challenge 1990;33:58-61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan CM, Oreglia A. California Life Expectancy: AbridgedLife Tables for California and Los Angeles County, 1989-1991.Sacramento: Dept of Health Services; 1993.

- 7.Wild SH, Laws A, Fortmann SP, Varady AN, Byrne CD. Mortality fromcoronary heart disease and stroke for six ethnic groups in California 1985 to1990. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:432-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elrick H. The Dual Focus Method of PatientCare. Bonita, CA: Foundation for Optimal Health and Longevity;1991.

- 9.Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, Suzuki M. The OkinawaProgram. New York, NY: Potter Publishers;2001.

- 10.Walker ARP. Survival rate at middle age in developing and westernpopulations. Postgrad Med J 1974;50:29-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindeberg S, Nilsson-Ehle P, Terent A, Vessby B, Schersten B.Cardiovascular risk factors in a Melanesian population apparently free fromstroke and ischaemic heart disease: the Kitava study. J InternMed 1994;236:331-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page LB, Damon A, Moellering RC Jr. Antecedents of cardiovasculardisease in six Solomon Islands societies. Circulation 1974;49:1132-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samaras TT, Storms LH. Impact of height and weight on life span.Bull World Health Organ 1992;70:259-267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samaras TT. How body height and weight affect our performance,longevity, and survival. J Wash Acad Sci 1996;84:131-156. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albanes D. Height, early energy intake and cancer: evidence mountsfor the relation of energy intake to adult malignancies.BMJ 1998;317:1331-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebert PR, Ajani U, Cook NR, Lee IM, Chan KS, Hennekens CH. Adultheight and incidence of cancer in male physicians (United States).Cancer Causes Control 1997;8:591-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartke A. Delayed aging in Ames dwarf mice: relationships toendocrine function and body size. In: Hekimi Z, ed. The MolecularGenetics of Aging: Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation.Vol 29. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer;2000: 181-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rollo CD, Carlson J, Sawada M. Accelerated aging of gianttransgenic mice is associated with elevated free radical processes.Can J Zool 1996;74:606-620. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Deeb B, Pendergrass W, Wolf N. Cellular proliferativecapacity and life span in small and large dogs. J Gerontol A BiolSci Med Sci 1996;51:B403-B408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samaras TT, Storms LL. Secular growth and its harmfulramifications. Med Hypotheses 2002;58:98-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]