Abstract

Although Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels are modulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. In this study, we investigated effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on the Ca2+ channel using a patch-clamp technique in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Externally applied H2O2 (1 mM) increased Ca2+ channel activity in the cell-attached mode. A specific inhibitor of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) KN-93 (10 μM) partially attenuated the H2O2-mediated facilitation of the channel, suggesting both CaMKII-dependent and -independent pathways. However, in the inside-out mode, 1 mM H2O2 increased channel activity in a KN-93-resistant manner. Since H2O2-pretreated calmodulin did not reproduce the H2O2 effect, the target of H2O2 was presumably assigned to the Ca2+ channel itself. A thiol-specific oxidizing agent mimicked and occluded the H2O2 effect. These results suggest that H2O2 facilitates the Ca2+ channel through oxidation of cysteine residue(s) in the channel as well as the CaMKII-dependent pathway.

Keywords: Calcium channel, Reactive oxygen species, H2O2, Calmodulin, Cardiac myocytes

Introduction

An alteration in the cell’s redox state such as increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is associated with pathology [1–3]. In the heart, ROS as highly reactive compounds accumulate in tissues during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion and cause peroxidation of lipids and proteins [4] which play an important role in the pathogenesis of ischemia/reperfusion abnormalities, including myocardial stunning, irreversible injury, and reperfusion arrhythmias [5]. ROS-induced Ca2+ overload is one of the major causes of cardiomyocytes injury during ischemia/reperfusion [6]. Ca2+ overload induced by oxidation is thought to be mediated by increased Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) through the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor 2, RyR2) and decreased Ca2+ uptake by inhibiting Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) activity [7].

L-type (Cav1.2) Ca2+ channels (LTCCs) in the myocardium sarcolemma are the main route for Ca2+ influx into cells. Different from skeletal muscle, in cardiac myocytes, Ca2+ influx through LTCCs triggers Ca2+ release, thus determining the Ca2+ dynamics in the cardiac myocytes. Accumulating evidence shows that basal activity of LTCCs is modulated by cytoplasmic factors including protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation [8, 9], phosphatase-mediated dephosphorylation [8, 9], and the interaction with Ca2+ and Mg2+ [10], lipids [11] and proteins [12, 13]. Recent studies suggest that the function of LTCC is crucially modulated by ROS during ischemia/reperfusion [14, 15]. Exposure of myocytes to high concentration of H2O2 results in alteration of Ca2+ channel activity and cellular Ca2+ homeostasis [16]. However, the effects of oxidation are so far controversial, since both inhibition and facilitation of LTCCs by oxidation have been suggested [17–20]. The mechanism of the ROS effect on LTCCs also remains elusive. For example, H2O2 has been suggested to facilitate LTCCs by activation of Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) through oxidation of methionin residues in CaMKII or increasing Ca2+ release through RyR (20). On the other hand, Tang et al. [19] have reported that H2O2-induced facilitation of LTCCs is mediated by glutathionylation of LTCCs.

To explore the effect of oxidation on cardiac LTCCs and the underlying mechanisms, the inside-out mode of the patch-clamp technique is beneficial since the internal side of LTCC can be well controlled. We have previously found that LTCC activity is maintained with calmodulin (CaM) and ATP without run-down of the channel in the inside-out patches [12, 21–26]. In this study, using this method, we have investigated the effect of H2O2 on the current through LTCCs. H2O2 was found to increase Ca2+ channel activity in both the cell-attached mode and the inside-out mode. The specific CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 partially attenuates the facilitation effect in the cell-attached mode, but had no effect in the inside-out mode. Our results suggest that H2O2 facilitates LTCCs through CaMKII-dependent and -independent pathways.

Materials and methods

Materials

MgATP, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) tablet, and 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DNTB) (cysteine residue oxidation reagent) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), KN-93 (CaMKII inhibitor) and KN-92 (inactive analog of KN-93) were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA), and Bay K8644 (Ca2+ channel agonist) was from Wako (Osaka, Japan).

Preparation of single cardiac myocytes

Single ventricular myocytes were isolated from adult guinea pig hearts by collagenase dissociation as described previously [27]. In brief, a female guinea pig (weight 300–500 g) was anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg, i.p.), and the aorta was cannulated in situ under artificial respiration. The dissected heart was mounted on a Langendorff apparatus and perfused with Tyrode solution for 3 min, then with nominally Ca2+-free Tyrode solution for 5 min, and finally with Ca2+-free Tyrode solution containing collagenase (0.08 mg/ml; Yakult) for 7–15 min. The collagenase was washed away with a high K+, low Ca2+ solution (storage solution). The single ventricular myocytes were dispersed and filtered through a stainless steel mesh (105 μm). Then, 0.05 mg/ml protease (Type XIV, Sigma) and 0.02 mg/ml DNase I (Type IV, Sigma) were incubated with the myocytes to improve the success rate in attaining a gigaohm seal. The enzyme-treated myocytes were then washed twice by centrifugation (800 rpm for 3 min) and stored at 4 °C.

The experiments were carried out under the approval of the Committee of Animal Experimental, Kagoshima University.

Solutions

The tyrode solution contained (in mM) 135 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 1.0 MgCl2, 5.5 glucose, 1.8 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES–NaOH buffer (pH 7.4). The storage solution was composed of (in mM) 70 KOH, 50 glutamic acid, 40 KCl, 20 KH2PO4, 20 taurine, 3 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 0.5 EGTA; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 50 BaCl2, 70 tetraethylammonium chloride, 0.5 EGTA, 0.003 BAY K8644, and 10 HEPES-CsOH buffer (pH 7.4). The basic internal solution consisted of (in mM) 90 potassium aspartate, 30 KCl, 10 KH2PO4, 1 EGTA, 0.5 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES–KOH buffer (pH 7.4; free Ca2+ 80 nM, pCa 7.1). CaM and MgATP were dissolved in basic internal solution in the inside-out patch mode.

Preparation of CaM

The cDNA of human CaM cloned into the pGEX6P-3 vector (GE Healthcare Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden) was expressed as glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified using glutathione–Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). The GST region was cleaved by PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare). The purity of CaM was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and quantified by the Bradford method (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) with bovine serum albumin as the standard and a correction factor of 1.69.

Patch clamp and data analysis

Barium current through LTCCs was recorded in the cell-attached and inside-out mode using the patch-clamp technique. For recording in the cell-attached mode, the myocytes were perfused with the basic internal solution at 31–35 °C using a patch pipette (2–4 MΩ) containing 50 mM Ba2+ and 3 μM Bay K8644. Bay K8644, a Ca2+ channel agonist, was used to prolong the open time of the channel to facilitate the experiments. Barium currents through LTCCs were elicited by depolarizing pulses from −70 to 0 mV for 200 ms duration at a rate of 0.5 Hz. The current were recorded with a patch-clamp amplifier (EPC-7; List, Darmstadt, Germany) and fed to a computer at a sampling rate of 3.3 kHz. The mean current (I) was measured and divided by the unitary current amplitude (i) to yield NPo, based on the equation I = N × Po × i, where N is the number of channels in the patch and Po is the time-averaged open-state probability of the channels. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. Student’s t test or ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was used to estimate statistical significance and values of P < 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

H2O2 facilitated Ca2+ channel in the cell-attached mode via CaMKII-dependent and independent pathways

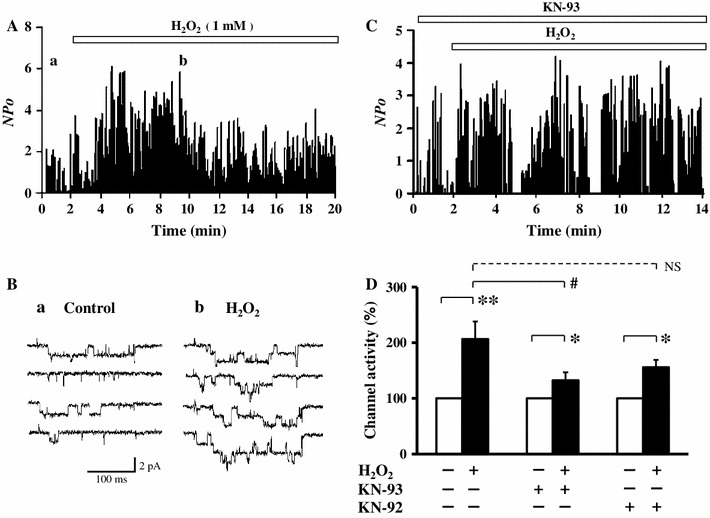

We first examined the effect of H2O2 on the current through LTCCs in the cell-attached mode in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. After recording the current for 2 min as a control, 1 mM H2O2 was applied in the perfusion solution. As shown in Fig. 1a, b, Ca2+ channel activity was rapidly increased without a change in the unitary current amplitude. In an average of six patches, Ca2+ channel activity was increased to 206 ± 32 % of the control (Fig. 1d). This result confirmed the facilitating effect of H2O2 on LTCCs.

Fig. 1.

H2O2 facilitates L-type Ca2+ channel activity in cell-attached mode. a Time course of channel activity (NPo) recorded in the cell-attached mode before and after application of 1 mM H2O2. b Examples of current traces of the Ca2+ channels before (a) and after (b) application of H2O2 taken at the times indicated in (a). c Effect of 1 mM H2O2 on channel activity (NPo) recorded in cell-attached mode in the presence of 10 μM KN-93. d Summary of the normalized activity of the Ca2+ channel treated with H2O2 with no drug (n = 6), and with 10 μM KN-93 (a specific CaMKII inhibitor) (n = 9) or KN-92 (an inactive form of KN-93) (n = 5). Mean channel activity (60 traces) in each patch was normalized to the corresponding control value, averaged in the same group, and shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus control (Student’s t test), and # P < 0.05 and NS not significant versus H2O2 without drug (ANOVA and Tukey HSD test)

Facilitation of LTCCs by glutathionylation [19] or phosphorylation mediated by activated CaMKII [20] during oxidative stress has been proposed. To evaluate the possible CaMKII-dependent effect of H2O2, we incubated the cardiomyocytes with 10 μM KN-93, a specific CaMKII inhibitor, for 10 min before recording the current. Under this condition, it has been reported that the activity of CaMKII is nearly completely inhibited by KN-93 [28, 29]. As shown in Fig. 1c, KN-93 significantly attenuated H2O2-mediated facilitation [132 ± 15 % (n = 9) vs. 206 ± 32 % with no drug, P < 0.05], while KN-92, an inactive analog of KN-93, partially attenuated the facilitation but it was not statistically significant [156 ± 13 % (n = 5) vs. 206 ± 32 % with no drug, P = 0.30). These results suggested that not only CaMKII-dependent but also independent pathways were involved in H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCCs.

H2O2 facilitated Ca2+ channel in the inside-out mode independently of CaMKII

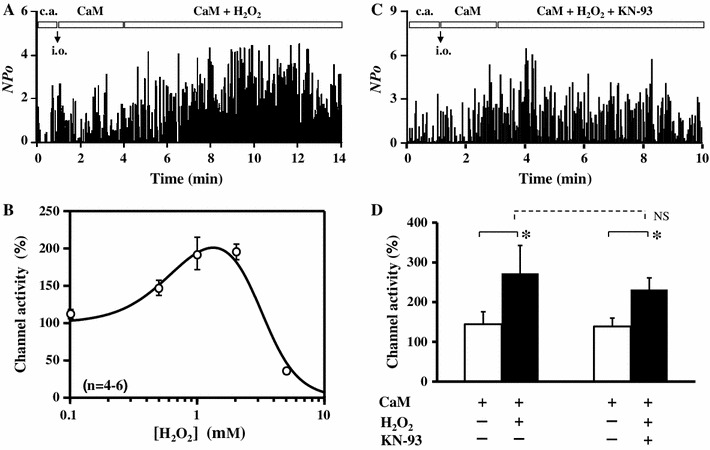

To explore the mechanism of CaMKII-independent facilitation of LTCCs produced by H2O2, we investigated the H2O2 effect on LTCCs in the inside-out patches in which the Ca2+ channel activity was maintained by application of 1 μM CaM together with 3 mM ATP [12, 21–26]. In the inside-out patch mode, LTCCs were disconnected with cytoplasmic factors and perfused with an artificial solution with known composition. This was quite beneficial to examine direct effects of external reagents on LTCC. After the patch was excised and moved to a small inlet in the perfusion chamber, which was connected to a microinjection system, CaM/ATP was immediately applied to induce Ca2+ channel activity, the single channel current was recorded for 3 min as a control current, then 1 mM H2O2 was added to the CaM/ATP solution. As shown in Fig. 2a, H2O2 significantly increased the CaM-induced Ca2+ channel activity in the inside-out mode. This facilitatory effect of H2O2 was concentration-dependent up to 1–2 mM, and higher concentrations of H2O2 conversely inhibited Ca2+ channel activity presumably due to a non-specific deteriorating effect of H2O2 (Fig. 2b). These results suggested that H2O2 (<2 mM) facilitated Ca2+ channel activity in the inside-out patches via a direct modification of LTCC and/or its closely-located proteins such as CaM and CaMKII. To assess the possibility that CaMKII was still located near the channel and modulated channel activity in the excised patches, we examined the effect of KN-93 in the inside-out patches. As shown in Fig. 2c, KN-93 had only a small effect on the H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCCs in the inside-out mode. In summary, channel activity was modulated by H2O2 from 144 ± 32 % (control) to 272 ± 70 % in the absence of KN-93 (n = 5), whereas the change was from 139 ± 21 to 231 ± 29 % in the presence of KN-93 (n = 6). Although KN-93 seemed to slightly attenuate the increasing effect of H2O2 on channel activity, this difference was statistically insignificant. Thus, KN93 did not significantly affect the H2O2-mediated facilitation of the Ca2+ channel in the inside-out mode.

Fig. 2.

H2O2-mediated facilitation of Ca2+ channel activity in inside-out mode. a, c Time course of channel activity (NPo) recorded in the cell-attached (c.a.) mode followed by the inside-out (i.o.) mode, in which channel activity was maintained with 1 μM CaM + 3 mM ATP, and then 1 mM H2O2 without (a) or with (c); 10 μM KN-93 was additionally applied as indicated by the boxes in each graph. ATP was included throughout the experiments in the i.o mode. b Concentration-dependent effect of H2O2. Normalized channel activity was plotted against concentration of H2O2. Data (n = 4–6) were fitted with a combined Hill’s equation as: , where [H2O2] was the concentration of H2O2, A the extent of facilitation, Kdf and Kdi apparent dissociation constants, and n f and n i Hill’s numbers for facilitation and inhibition, respectively. The fitted curve was drawn with A = 147, Kdf = 0.68 mM, n f = 2, Kdi = 3.11 mM, and n i = 3 (r 2 = 0.983). d Summary of the normalized channel activity in the presence of CaM + ATP in i.o. mode before and after addition of H2O2 ± KN-93 (n = 5–6). Data are shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 versus CaM (t test), NS not significant (ANOVA)

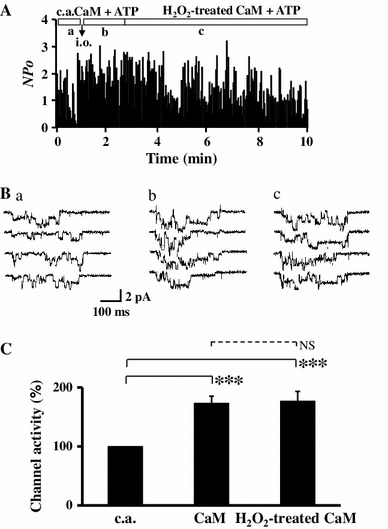

H2O2 may also be able to oxidize CaM and modulate the effect of CaM on Ca2+ channel activity. To assess this possibility, we examined the effect of oxidized CaM pretreated with 1 mM H2O2 at room temperature for 30 min. As shown in Fig. 3a, b, after Ca2+ channel activity was maintained by intact (untreated with H2O2) CaM + ATP in the inside-out patches, we substituted the oxidized CaM for the untreated CaM. Channel activity did not change significantly, suggesting that CaM was not oxidized or that oxidized CaM, if any, had similar potency as the untreated CaM on activity of LTCC (Fig. 3c). This result suggested that oxidation of CaM was not involved in the H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCCs, and thus a direct oxidation of LTCCs might be a possible mechanism for the facilitation in the inside-out mode.

Fig. 3.

Facilitation of Ca2+ channel by H2O2 is not due to oxidation of CaM. CaM was pre-incubated with 1 mM H2O2 for 30 min and then applied to the Ca2+ channels. a Time course of channel activity recorded first in the cell-attached (c.a.) mode followed by the inside-out (i.o.) mode with 1 μM non-treated (intact) CaM + 3 mM ATP, followed by substitution with H2O2-treated CaM (1 μM). b Example of current traces for the control in c.a. mode (a), with CaM + ATP in i.o mode (b), and H2O2-treated CaM + ATP (c), at the time period indicated in (a). c Summary of normalized channel activity induced by CaM + ATP (n = 7) and H2O2-treated CaM + ATP (n = 6). Data are shown as mean ± SE. ***P < 0.001 versus control (c.a.), NS not significant (ANOVA and Tukey HSD test)

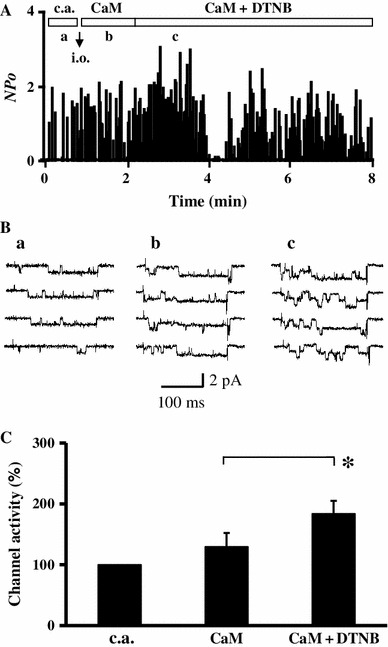

Cysteine residues in Ca2+ channel are involved in H2O2-mediated facilitation

The α1C subunit of LTCC contains 38 cysteine residues and 36 methionine residues in the cytoplasmic chains, which are potentially subject to oxidation modification. To identify the amino acid residue which was oxidized by H2O2 and responsible for the H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCCs, a specific oxidizing agent of cysteine residues 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) was applied in place of H2O2. As shown in Fig. 4, 1 mM DNTB significantly increased Ca2+ channel activity maintained by CaM (from 129 ± 22 up to 184 ± 21 %, n = 5), suggesting that oxidation of cysteine residue(s) was responsible, at least partially, for the H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCCs. Since there is no specific oxidizing agent of methionine residues available, we examined the effects of H2O2 on LTCC after application of DTNB. Application of H2O2 + CaM after DTNB + CaM only slightly increased Ca2+ channel activity and was statistically insignificant (Fig. 5). These results suggested that oxidation of cysteine residue(s) was the major cause of the H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCCs in the inside-out patches.

Fig. 4.

DTNB, a specific oxidant of cysteine residues, facilitates Ca2+ channel activity in inside-out mode. a Time course of channel activity recorded first in the cell-attached (c.a.) mode followed by the inside-out (i.o.) mode. After patch excision, 1 μM CaM + 3 mM ATP was applied to maintain channel activity, and then DTNB (1 mM) was additionally applied. b Example of current traces for control in c.a. mode (a), with CaM + ATP in i.o mode (b), and with CaM + ATP + 1 mM DTNB (c) at the time period indicated in (a). c Summary of normalized channel activity in the presence of CaM + ATP and CaM + ATP + DTNB (n = 5). Data are shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 versus control (t test)

Fig. 5.

a Time course of channel activity recorded first in the cell-attached (c.a.) mode followed by the inside-out (i.o.) mode. After patch excision, 1 μM CaM + 3 mM ATP was applied to maintain channel activity, then DTNB (1 mM) was added, and finally H2O2 (1 mM) was additionally applied. b Summary of channel activity induced by CaM + ATP + DTNB (n = 5) and CaM + ATP + H2O2 (n = 6), normalized to the activity values obtained for conditions of CaM + ATP. Data are shown as mean ± SE. NS not significant (t test)

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effect of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) of cardiac myocytes in the cell-attached and the inside-out mode. We found that H2O2 facilitates cardiac LTCCs through two pathways: (1) direct oxidation of cysteine residue(s) of the channel, and (2) indirect pathways via activation of CaMKII.

Changes of the redox state in the cardiac myocytes play an important role in heart diseases. LTCC as a major regulator of cardiac function is subject to redox modification. Although there is accumulating evidence supporting that ROS modulate the function of LTCCs, the results of these studies are somehow controversial. Oxidizing agents are reported to inhibit the human and rabbit cardiac LTCC expressed in HEK293 cells [17, 18]. In isolated guinea pig ventricular myocytes, oxidation decreased the current through LTCC [30]. On the other hand, a decrease in cellular superoxide and H2O2 is associated with a decrease in the current of native [31, 32] and expressed LTCCs [17, 33], while the thiol-specific oxidizing agent, DNTB, increases the LTCC current [34]. The complicated interactions between LTCC and uncontrolled cytoplasmic factors may be partially responsible for the uncertainty surrounding the effects of oxidation on LTCCs. The present study took advantage of the inside-out mode of patch-clamp technique in which most of the cytoplasmic factors were washed out [12, 21–26]. Our results show that H2O2 facilitates LTCC at concentrations up to 2 mM and inhibits the channel at higher concentrations. This finding may partly account for the diverse results in the previous studies.

The underlying mechanisms of modulation of the Ca2+ channel by H2O2 are so far not completely clear. Song et al. [20] have reported H2O2-mediated facilitation of the Ca2+ channel through activation of CaMKII which can be activated by either Ca2+/CaM or oxidation of methionine residues in CaMKII. Thus, H2O2 is involved in both activation processes: (1) H2O2 enhances Ca2+ release from SR by increasing RYR activity; (2) oxidation of methionine residues (281/282 in mouse) in CaMKII protein sustains the kinase activity independent of Ca2+/CaM [3]. However, Tang et al. [19] suggest that H2O2 facilitates the Ca2+ channel through direct glutathionylation of the channel protein. It is difficult to distinguish the direct effect of H2O2 from an indirect one when examining whole-cells. In the present study, we employed a method to record LTCC current in the inside-out mode, in which channel activity was maintained by CaM/ATP in the internal solution [12, 21–26]. Our results show that the CaMKII-specific inhibitor, KN-93, did not completely attenuate H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCC in the cell-attached mode, suggesting that H2O2-mediated facilitation is mediated not only by a CaMKII-dependent pathway but also by CaMKII-independent pathways. The finding that KN-93 does not inhibit the H2O2 effect in the inside-out mode indicates that the CaMKII-mediated facilitation is absent in the inside-out mode, and hence implies that CaMKII might not be attached to LTCC or, if present, it might not be in a state sensitive to oxidation in our inside-out patches.

Thus, our results indicate that, in addition to the CaMKII-dependent pathway, there is an additional CaMKII-independent pathway for the H2O2-mediated facilitation of LTCC. Since most intracellular proteins are washed out in the inside-out patches, it is likely that direct oxidation of LTCC or its associated proteins by H2O2 might be involved in the facilitation of LTCC. Since H2O2-pretreated CaM does not mimic the facilitatory effect of H2O2, oxidation of CaM does not account for the mechanism of facilitation. This is consistent with the fact that human CaM does not contain any cysteine residues. Thus, it seems most likely that the Ca2+ channel protein itself undergoes direct oxidation by H2O2 as the CaMII-independent pathway of the LTCC facilitation.

Both cysteine and methionine residues are subject to oxidation by H2O2. The pore-forming subunit α1C of cardiac LTCC is rich in cysteine and methionine residues in the cytoplasmic chains [35]. Our findings that the specific cysteine oxidizing agent DTNB mimics the H2O2 effect and that the effect of subsequently applied H2O2 is largely occluded suggest that cysteine residue(s) are involved in the H2O2-mediated facilitation. However, this does not exclude a possible involvement of methionine residue(s). Future work should focus on determining the oxidation sites responsible for the H2O2-mediated modulation of LTCC. In conclusion, LTCC may undergo ROS-mediated modification via the direct oxidation of LTCC as well as the indirect pathways involving CaMKII activation. This would be relevant for the understanding of ROS-mediated regulation of ion channels and Ca2+ overload and arrhythmogenesis during oxidation stress on the heart.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. E. Iwasaki for secretarial work on the manuscript, and the Institute of Laboratory Animal Sciences and Joint Research Laboratory of our Graduate School, Kagoshima University for the use of their facilities. L.Y. thanks Profs. L.Y. Hao and T. Zhu for their continuous encouragement. This work was supported by research grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to M.K. and E.M. and from the Kodama Memorial Foundation to J.J. Xu.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Doerries C, Grote K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Luchtefeld M, Schaefer A, Holland SM, Sorrentino S, Manes C, Schieffer B, Drexler H, Landmesser U. Critical role of the NAD(P)H oxidase subunit p47phox for left ventricular remodeling/dysfunction and survival after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2007;100:894–903. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261657.76299.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinugawa S, Tsutsui H, Hayashidani S, Ide T, Suematsu N, Satoh S, Utsumi H, Takeshita A. Treatment with dimethylthiourea prevents left ventricular remodeling and failure after experimental myocardial infarction in mice: role of oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2000;87:392–398. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.5.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O’Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halliwell B. The role of oxygen radicals in human disease, with particular reference to the vascular system. Haemostasis. 1993;23:118–126. doi: 10.1159/000216921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duan J, Moffat MP. Potential cellular mechanisms of hydrogen peroxide-induced cardiac arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;19:593–601. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199204000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:581–609. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zima AV, Blatter LA. Redox regulation of cardiac calcium channels and transporters. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan X, Gao S, Tang M, Xi J, Gao L, Zhu M, Luo H, Hu X, Zheng Y, Hescheler J, Liang H. Adenylyl cyclase/cAMP-PKA-mediated phosphorylation of basal L-type Ca2+ channels in mouse embryonic ventricular myocytes. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase and L-type calcium channels; a recipe for arrhythmias? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Tashiro M, Berlin JR. Regulation of L-type calcium current by intracellular magnesium in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;555:383–396. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.048538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Bauer CS, Zhen XG, Xie C, Yang J. Dual regulation of voltage-gated calcium channels by PtdIns(4,5)P2 . Nature. 2002;419:947–952. doi: 10.1038/nature01118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu JJ, Hao LY, Kameyama A, Kameyama M. Calmodulin reverses rundown of L-type Ca2+ channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1717–C1724. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00105.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen RX, Liu F, Li Y, Liu GA. Neuromedin S increases L-type Ca2+ channel currents through Giα-protein and phospholipase C-dependent novel protein kinase C delta pathway in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30:618–630. doi: 10.1159/000341443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hool LC. Evidence for the regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in the heart by reactive oxygen species: mechanism for mediating pathology. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:229–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos CX, Anilkumar N, Zhang M, Brewer AC, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac myocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:777–793. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viola HM, Arthur PG, Hool LC. Transient exposure to hydrogen peroxide causes an increase in mitochondria-derived superoxide as a result of sustained alteration in L-type Ca2+ channel function in the absence of apoptosis in ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2007;100:1036–1044. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000263010.19273.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fearon IM, Palmer AC, Balmforth AJ, Ball SG, Varadi G, Peers C. Modulation of recombinant human cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel alpha1C subunits by redox agents and hypoxia. J Physiol. 1999;514:629–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.629ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu H, Chiamvimonvat N, Yamagishi T, Marban E. Direct inhibition of expressed cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels by S-nitrosothiol nitric oxide donors. Circ Res. 1997;81:742–752. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.81.5.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang H, Viola HM, Filipovska A, Hool LC. Cav1.2 calcium channel is glutathionylated during oxidative stress in guinea pig and ischemic human heart. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1501–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song YH, Cho H, Ryu SY, Yoon JY, Park SH, Noh CI, Lee SH, Ho WK. L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation mediated by H2O2-induced activation of CaMKII in rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:773–780. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao LY, Xu JJ, Minobe E, Kameyama A, Kameyama M. Calmodulin kinase II activation is required for the maintenance of basal activity of L-type Ca2+ channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:290–300. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08101FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hao LY, Wang WY, Minobe E, Han DY, Xu JJ, Kameyama A, Kameyama M. The distinct roles of calmodulin and calmodulin kinase II in the reversal of run-down of L-type Ca2+ channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;111:416–425. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09094FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang WY, Hao LY, Minobe E, Saud ZA, Han DY, Kameyama M. CaMKII phosphorylates a threonine residue in the C-terminal tail of Cav1.2 Ca2+ channel and modulates the interaction of the channel with calmodulin. J Physiol Sci. 2009;59:283–290. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0033-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han DY, Minobe E, Wang WY, Guo F, Xu JJ, Hao LY, Kameyama M. Calmodulin and Ca2+-dependent facilitation and inactivation of the Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112:310–319. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09282FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo F, Minobe E, Yazawa K, Asmara H, Bai XY, Han DY, Hao LY, Kameyama M. Both N- and C-lobes of calmodulin are required for Ca2+-dependent regulations of CaV1.2 Ca2+ channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1170–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minobe E, Asmara H, Saud ZA, Kameyama M. Calpastatin domain L is a partial agonist of the calmodulin-binding site for channel activation in Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39013–39022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yazawa K, Kaibara M, Ohara M, Kameyama M. An improved method for isolating cardiac myocytes useful for patch-clamp studies. Jpn J Physiol. 1990;40:157–163. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.40.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrero P, Said M, Sánchez G, Vittone L, Valverde C, Donoso P, Mattiazzi A, Mundiña-Weilenmann C. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II increases ryanodine binding and Ca2+-induced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release kinetics during β-adrenergic stimulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao L, Fan P, Jiang Z, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Wu Y, Kornyeyev D, Hirakawa R, Budas GR, Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Nav1.5-dependent persistent Na+ influx activates CaMKII in rat ventricular myocytes and N1325S mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C577–C586. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00125.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lacampagne A, Duittoz A, Bolaños P, Peineau N, Argibay JA. Effect of sulfhydryl oxidation on ionic and gating currents associated with L-type calcium channels in isolated guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;30:799–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hool LC. Hypoxia increases the sensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ current to beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation via a C2 region-containing protein kinase C isoform. Circ Res. 2000;87:1164–1171. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.12.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hool LC. Hypoxia alters the sensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ channel to alpha-adrenergic receptor stimulation in the presence of beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation. Circ Res. 2001;88:1036–1043. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fearon IM, Palmer AC, Balmforth AJ, Ball SG, Mikala G, Schwartz A, Peers C. Hypoxia inhibits the recombinant alpha 1C subunit of the human cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel. J Physiol. 1997;500:551–556. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaoka K, Yakehiro M, Yuki T, Fujii H, Seyama I. Effect of sulfhydryl reagents on the regulatory system of the L-type Ca2+ channel in frog ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s004249900242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hool LC, Corry B. Redox control of calcium channels: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:409–435. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]