Summary points

Start with half the usual recommended starting dose because of possibleside effects

Explain that medications exert their full effects in weeks and not days andthat adherence is important in achieving and maintaining positive results

Minimize the use of benzodiazepines as monotherapy; if they are usedjointly with another agent, taper dosage completely after several weeks ortaper to the lowest effective dose

Explain medication treatment using a model that describes the relationshipsbetween the brain, brain chemicals, and the restoration of balance to improvesymptoms

Although evidence of the effectiveness of herbal treatments is scant, allowuse of some forms (eg, teas, soups) during continuation treatment if patientsinsist. Caution them, however, about possible interactions between herbs andmedication

Many recommendations have been made about the drug treatment of medicaloutpatients withdepression.1,2In this article, we do not attempt to repeat this guidance. Instead, we beginwith a focus on the education of Asian patients who require medication and theclinical principles that guide medication management. Then, we discussmedication for mood and anxiety disorders using the selective serotoninreuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and benzodiazepines. Finally, we address importantclinical issues related to the use of antipsychotic medications.

Using medications to treat Asian American patients with mental disorderscan be challenging. Because of the belief that Western medicines may be toostrong for their constitution, patients often experiment withmedications.3 Manyseek immediate symptom relief because of previous exposure to benzodiazepines.The desire by some Asians to use herbal treatments may result in untoward druginteractions.4

Based on our clinical experience in treating Asian American patients, webelieve that adopting a culturally appropriate model for prescribingmedication can help health care professionals manage these concerns and leadsto better treatment for Asian American patients.

PATIENT EDUCATION

Traditionally oriented Asians believe in the concept of maintaining balance(yin and yang, mind and body, hot and cold), and that thisbalance is integral to goodhealth.5 Health careproviders should use this concept of balance to explain how medication canhelp.

Explain that the patient's symptoms indicate an imbalance in brainchemicals that regulate mood, energy, emotion, and bodily sensations

Explain that medications restore the balance but time is needed for them towork because the symptoms have been present for some time and stress hasdepleted the supply of these chemicals

Emphasize the importance of taking medications daily and that you will workwith the patient, starting at a low dose and evaluating its efficacy beforeincreasing the dose

Tell the patient that some side effects are expected but that they are timelimited and generally mild if the proper dosage is used. Consider reframingside effects by saying that they are early indicators that the medicine isattempting to restore balance

Advise patients to avoid using any herbal medications during this acuteperiod of management. You can say that while you respect their views, herbalmedication use should be discussed when an optimal dose of the medicine hasbeen achieved. table 1

Do not call the psychotropic medication a “sleeping pill.”Instead, explain that symptoms will go away gradually. Family members andothers may notice improvement even before the patient does

To avoid the patient feeling abandoned by you, let the patient know thatyou will be available to manage the medications and answer questions duringthe course of treatment, even if you later refer the patient to aspecialist

Table 1.

RecommendedSSRls*

| Generic agent | Minimum effective dose, mg | Dose range, mg | Indications | Contraindications and warnings | Precautions | Special populations | Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram hydrobromide (Celexa) | 20-40 | 20-40 | Depression | Must not be prescribed with MAOIs | Data in the elderly available for depression; no data in children | Category C | |

| Paroxetine hydrochloride (Paxil) | 20, except 40 for panic disorder and OCD | 20-60 | Depression, OCD, panic disorder, SAD, GAD, PTSD | Must not be prescribed with MAOIs or thioridazine | Short elimination half-life leading to withdrawal-type side effects(discontinuation syndrome) | Data in the elderly available for depression, lower doses recommended; no datain children | Category C |

| Fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac) | 20, except 60 for bulimia | 20-80 | Depression, OCD, bulimia | Must not be prescribed with MAOIs or thioridazine; may cause rash more oftenthan other SSRIs (drug should be stopped if it causes a rash) | Long elimination half-life | Efficacy in the elderly for depression established, lower doses recommended;no data in children | Category C |

| Sertraline hydrochloride (Zoloft) | 50 | 50-200 | Depression, PMDD, OCD, panic disorder, PTSD | Must not be prescribed with MAOIs | Data in the elderly available for depression; efficacy in children with OCDand safety data up to 1 year established | Category C |

Note: The proprietary names included (in parentheses) are for informationonly and should not be construed as endorsement of a particular brand by theauthors or wjm editors.

US prescribing information, Physicians Desk Reference 2001. SSRI =selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; OCD = obsessive complusive disorder;PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SAD = social anxiety disorder; GAD =generalized anxiety disorder; MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor; PMDD =premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

ANTIDEPRESSANTS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first line oftreatment of mood and anxiety disorders. They have demonstrated efficacy, arebetter tolerated than tricyclic antidepressants, and are safer in the event ofoverdose. The Table shows the four most commonly prescribed SSRIs in the USmarket. Each of these medications is currently approved for the treatment ofmajor depressive disorder. Several also are approved for use in the treatmentof anxiety disorders such as panic disorder and posttraumatic stressdisorder.

Although these medications are used by some physicians beyond theirapproved indications (off-label prescribing), the comfort level of cliniciansfor this type of prescribing varies by practice specialty. In this briefreview, we restrict our discussion to approved indications, because they showthat the drug's efficacy and safety have been reviewed and approved by the USFood and Drug Administration. Any differences between different SSRIsmentioned in the table are directly referenced from the approved productlabeling and are only mentioned when the drug is different from the group as awhole.6

Choice of SSRI

The prescribing clinician should consider the approved indications,individual patient preferences, response to previous treatment, andanticipated side effects when choosing an SSRI to treat mood or anxietydisorders.7

Efficacy Optimizing treatment with a single antidepressant agent inprimary care is a critical goal. This involves keeping patients on a single-medication regimen for up to 4 to 6 weeks to evaluate response and thenadjusting the doseaccordingly.8

Tolerability Commonly cited side effects of SSRIs include mildanxiety, insomnia, minor gastrointestinal discomfort, and sexual dysfunction.These side effects tend to be time limited and self limited (2 to 4 weeks) andmay be dose related.

Safety SSRIs as a class should not be prescribed for patientsreceiving monoamine oxidase inhibitors (such as phenelzine). Coadministrationwith antidepressant drugs that increase serotonin causes norepinephrine andother sympathetic precursors to accumulate, which can result in serious,sometimes fatal reactions, including hypertensive crises. Metabolism ofpsychotropic medications mostly involves cytochrome P450 enzymes. The beststudied of these drug metabolizing enzymes is CYP450 2D6. Fluoxetinehydrochloride and paroxetine hydrochloride are potent inhibitors of CYP4502D6. Therefore, they are more likely than citalopram hydrobromide orsertraline hydrochloride to cause undesirable drug-drug interactions. Thisdiscussion of drug coadministration may be particularly relevant in Asiansbecause evidence suggests that there are more poor and slow metabolizers ofCYP450 2D6 among Asians than in the general USpopulation.9

Special populations Sertraline hydrochloride has been proven safeand effective for up to 1 year when treating obsessive-compulsive disorder inchildren andadolescents.10 AllSSRIs are safe to administer to elderly patients. Fluoxetine hydrochloride hasproved effective in treating depression in the elderly. All SSRIs arepregnancy category C, meaning that few data on their safety in pregnancy areavailable, and they may have teratogenic effects based on high dosages used inanimals. Therefore, a careful risk-benefit analysis should be undertakenbefore prescribing SSRIs in pregnancy. Consultation with a specialist isrecommended.

Use in Asian patients

To minimize potential adverse effects and to increase patient comfort withthe idea that medication can be beneficial, we prescribe no more than half thecustomary starting dose for Asian patients. Reasons why many Asians developside effects at lower doses compared to other ethnic groups remain unclear butmay involve biologic mechanisms (eg, Asians metabolize drugs in the CYP4502D6 system more slowly than other ethnic groups and they have a lowerbody weight) or environmental factors (eg, diet or patient expectation of sideeffects).9

An assessment of the effects of therapy should be made no later than 2weeks after starting a medication regimen. This assessment can be done byphone or during an office visit. This contact also allows the health careprovider the opportunity to reinforce his or her relationship with thepatient.

Explaining to the patient that the effect will not be immediate willincrease adherence to the therapy plan. About 60% of patients show a responseto the first antidepressant used, and an additional 20% will benefit from analternative agent if the first agent is noteffective.11

Self-adjustment of doses of medication is common in traditionally orientedAsian patients. We recommend explaining up front that decisions about andadjustments to dosage should be made together with the prescribing clinician.Although starting with a lower than standard dose is useful to improveadherence and tolerability, the full dose range of a drug should be used tothe point of intolerable side effects or suboptimal response before switchingto another agent. Although many Asians metabolize psychotropic drugs slowly,some Asian patients are normal or extensive metabolizers at the responsiblemetabolic pathway for the clearance of the drug and so will have near normaldose levels.

Taking a careful medication history and personal inspection of anymedication bottles brought by the patient can be informative. Patients mayalready be using medications that were obtained from friends or localpharmacies. When this situation occurs, referral to a psychiatrist forconsultation is recommended.

We also caution patients about taking herbal or other pharmaceuticals thatexert a psychotropic effect. Immigrant Asian patients may have medicines fromtheir native country that they or others have retained, some of which arepsychotropic agents that have been rebranded and sold as medicines for“nerves” or for restoring vitality. The effects of such agents canconfound the clinical picture, and their use may lead to untoward drug-druginteractions. If the patient insists on continuing their use, we recommendtheir use only after reaching an optimal dosage of the prescribed regimen orin continuation therapy with consultation from theprovider. table 2

Table 2.

| Side effects of conventional antipsychotics |

|---|

|

Because sleep relief is important to patients, a sedating serotonergicagent such as trazodone hydrochloride (25 to 50 mg) or a benzodiazepine (seebelow for special considerations) can be prescribed until the antidepressantmedication is effective.

ANXIOLYTICS AND HYPNOTICS

Adding an anxiolytic or hypnotic agent to the SSRI regimen to treat moodand anxiety disorders can be helpful for patients with insomnia or agitation.Relief of these symptoms using SSRIs alone generally takes 1 to 2 weeks,whereas symptom relief is almost immediate (although short-lived) withbenzodiazepines.

Choice of agent

Commonly used benzodiazepines are diazepam, alprazolam, lorazepam, andclonazepam. When benzodiazepines are used in conjunction with antidepressants,frequent monitoring is recommended to avoid the development of tolerance anddependence that are associated with chronic benzodiazepine use. The dosage ofbenzodiazepines should be tapered when the SSRI starts to have an effect (2 to4 weeks).

Use in Asian patients

For many immigrant patients, benzodiazepines have already been prescribedin their country of origin to treat mood and anxiety disorders. In many cases,more than one benzodiazepine is prescribed and long-term tolerance anddependence may occur. In some Asian countries, benzodiazepines are availablewithout a physician's prescription.

If possible, benzodiazepine use should be avoided by patients with ahistory of or ongoing problem with substance abuse.

When a benzodiazepine must be used to control an acute panic attack,clonazepam (FDA approved) is preferred. Clonazepam has an intermediate onsetand is longer acting, and therefore carries less potential for abuse, thanalprazolam (fast onset and short-acting) and diazepam (fast onset).

“Start low and go slow” is the rule of thumb when startingbenzodiazepine therapy in Asian patients because initial oversedation can beavoided and Asians may have slower metabolism ofbenzodiazepines.12The need for continued benzodiazepine use should be reassessed frequently.

ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATION

The primary care clinician usually does not initiate therapy with anantipsychotic medication except in emergency circumstances. In general,patients with psychotic symptoms should be referred to a psychiatrist forconsultation and evaluation. Primary care practitioners should, however, havea working knowledge of the common first-line antipsychotic agents. Becausemany Asian patients have poor access to mental health specialty treatment,primary care physicians often see patients who are receiving these medicationsand occasionally adjust doses when the patients are receiving routine medicalcare.

Choice of agent

The two main classes of antipsychotic medication are:

Conventional antipsychotics (dopamine receptor antagonists), such aschlorpromazine and haloperidol

Atypical antipsychotics (serotonin-dopamine antagonists), such asclozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone

Although both classes improve the positive symptoms of psychosis(hallucinations and delusions), atypical antipsychotics also improve negativesymptoms (apathy, anhedonia, social withdrawal). The side effects ofconventional antispychotics are shown in the Box. Atypical antipsychotics mayhave significantly fewer side effects, especially extrapyramidal symptoms, andthey are less often associated with tardive dyskinesia (a disabling,disfiguring movement disorder that may occur with long-term exposure toantipsychotic medication). Because of a better side effect profile and theeffect on negative symptoms, we believe that atypical agents are thefirst-line treatment for psychosis.

Use in Asian patients

Similar to their response to antidepressants and benzodiazepines, Asianpatients often respond to lower doses of antipsychotic medication. They mayalso experience side effects at lower doses than are seen in other ethnicgroups.13,14,15,16When initiating treatment in Asian Americans, we prescribe a starting dosethat is approximately one-half the standard recommended dose. Lower finaldosages should not be strictly assumed for every individual Asian patientbecause some may require the full typical doses.

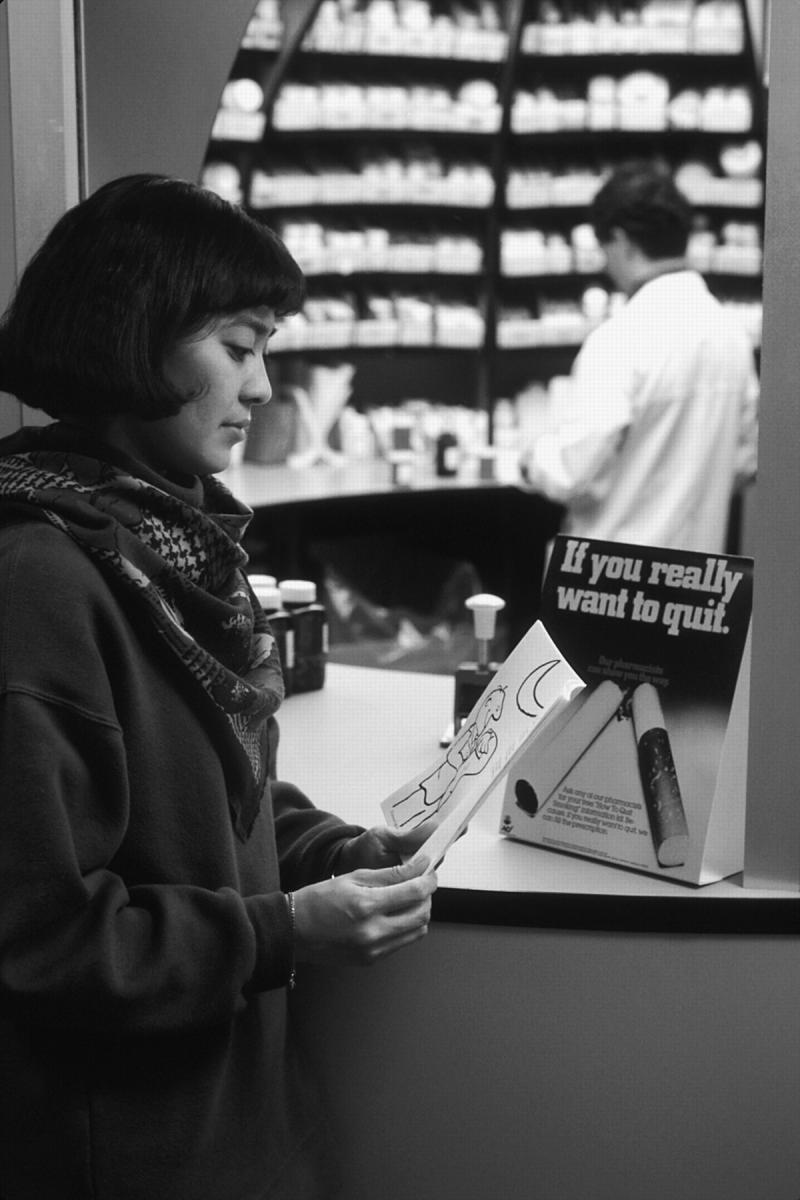

Figure 1.

Bill Branson/NCI

Careful patient education of Asians who require prescription medication formental illness is integral to a positive outcome

Figure 2.

Ask patients to bring in all medications that they are taking and inspectthem closely

Competing interests: J-P Chen and K-M Lin received speakerfees/educational grants and travel assistance, respectively, from Pfizer,Inc.; H Chung is Medical Director, Depression and Anxiety Disease ManagementTeam, Pfizer, Inc.

References

- 1.Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients.N Engl J Med 2000;343:1942-1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr, Chiquette E, et al. Efficacy of newermedications for treating depression in primary care patients. Am JMed 2000;108:54-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin KM, Cheung F. Mental health issues for Asian Americans.Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:774-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith M, Lin KM, Mendoza R. Nonbiological issues affectingpsychopharmacotherapy: cultural considerations. In: Lin KM, Poland R, NakasakiG, eds. Psychopharmacology and Psychobiology ofEthnicity. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press,1993; 37-58.

- 5.Lin KM. Traditional Chinese medical beliefs and their relevance formental illness and psychiatry. In: Kleinman A, Lin TY, eds. Normaland Abnormal Behavior in Chinese Culture. Boston: ReidelPublishing, 1981.

- 6.Prescribing Information, Celexa, Paxil, Prozac, Zoloft.Physicians Desk Reference, 2002 Montvale, NJ: MedicalEconomics, 2002.

- 7.Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical PracticeGuidelines, Number 5. Depression in Primary Care 1: Detection andDiagnosis. Rockville, MD: Dept of Health and Human Services,Agency for Health Policy and Research; AHCPR Publ No. 93-0550:52, 1993.

- 8.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care fordepressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch GenPsychiatry 2001;58:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin KM. Biological differences in depression and anxiety acrossraces and ethnic groups. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62 (Suppl) 13:13-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook EH, Wagner, KD, March JS, et al. Long-term sertralinetreatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:1175-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon GE. Choosing a first-line antidepressant: equal on averagedoes not mean equal for everyone. JAMA 2001;286-3003-3004 [editorial]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin KM, Smith MW. Psychopharmacology in the context of culture andethnicity. In: Ruiz P, ed. Ethnicity andPsychopharmacology. Review of Psychiatry, Vol19, No. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press;2000.

- 13.Lin KM, Finder E. Neuroleptic dosage for Asians. Am JPsychiatry 1983;140:490-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin KM, Poland RE, Nuccio I, et al. A longitudinal assessment ofhaloperidol doses and serum concentrations in Asian and Caucasianschizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1989;146:1307-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin TY. Psychiatry and Chinese culture. West JMed 1983;139:862-867. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binder RL, Levy R. Extrapyramidal reactions in Asians.Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:1243-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]