Summary points

Chinese patients base their decisions about using herbal medicines onfamily traditions, professional and quasi-professional recommendations, andself-medication

Because Chinese medicine does not separate mind and body, no herbs arespecified for use in patients with psychiatric conditions

Practitioners of Chinese medicine do prescribe herbs for physical symptomsthat Western physicians would consider as linked to a psychiatric illness

The main concerns about the use of herbal medicine are adulteration ofherbs with pharmaceuticals, adverse effects of the herbs themselves, andpossible herb-drug interactions

When asking patients about their use of herbs, open-ended inquiry couchedin supportive terms is likely the most helpful approach

In this article, we discuss the history and use of Chinese herbalmedicines, the Chinese medicine framework for understanding mental illness,and some concerns surrounding patients' use of traditional Chinesemedicines.

HISTORY

Since the emperor Shen Nong tasted 100 herbs and taught the Chinese peoplehow to use them in diet and therapy, herbal medicine has been an integral partof Chinese culture and medical practice. Descriptions of herbal therapy occurin the earliest texts that discuss Chinese medical practice. The traditionalChinese materia medica includes minerals and animal parts as well asherbs. Later materia medicae represented expanded inquiries into therange of pharmacologically active substances available to the Chinese.

In the 1977 Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese MedicinalSubstances, 5,767 substances are identified as part of thetraditional materiamedica.1 Thehuge number of substances listed is a result of extensive research into thetraditional folk applications of substances in different parts of rural China.A typical practitioner may routinely use between 200 and 600 substances.

DELIVERY FORMS

Of the various forms in which to deliver herbal medicines, water decoctionis probably used most widely. This process involves adding 1 to 13 medicinalagents, in quantities of 1 to 12 g each, to water and boiling it for about 45minutes. The liquid is separated from the herbs and drunk.

Raw herbs may also be consumed in powdered form. An industrial variant ofthe traditional preparation of raw herbs involves the production ofspray-dried concentrates, prepared in Japan, China, and Taiwan, withwell-documented quality control procedures. Another traditional deliverymethod is the honey pill, which is prepared by combining powdered herbs withconcentrated decoctions and honey to produce a small herbal pill. In someinstances, herbal extracts or powders are prepared using coating andencapsulation methods associated with pharmaceutical agents and supplements.Pills are prevalent and popular as over-the-counter remedies, and many arefound in community herb and grocery stores.

PERCEPTION AND TREATMENT OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN CHINESE MEDICINE

Chinese medicine does not separate mind and body. Instead, the psyche andsoma interact with each other. Psychological and emotional experiences canaffect the body and vice versa. In this sense, spirit is linked both to thehealth of the body and to the health of the mind. Similarly, aspects of humanexperience, such as anger, that are considered psychological in a Westernbiomedical frame of reference are linked in Chinese medicine to specificorgans. Anger is related to the liver, obsessive thought to the spleen, andjoy to the heart.

No specific constellations of “psychotropic” herbs or medicinalagents are prescribed routinely for specific mental conditions. In addition,given the cultural predisposition to somatization, it may be unclear, in someinstances, whether a mental disorder is being treated at all. In Chinesemedicine, clinical presentations that are associated with neurosis (shenjing guan neng zhong) include a wide range of complaints that havedistinct physical effects (see box1).

Box 1.

Clinical presentations associated with mental disorders in Chinesemedicine2

|

Even the term “depression” has a somatic linkage. Depression isunderstood as a disruption of normal emotionalactivity,3 relatedto the stagnation of qi (vital substance) caused by “affectdamage” (the ability of emotional excesses to damage the internalorgans). In Chinese medicine, depression requires differential diagnosis andappropriate treatment. Patterns associated with stagnation of liverqi, heat related to the insufficiency of yin, stomach heat,and the insufficiency of heart and spleen blood may all be variouslyimplicated.

SOURCES OF MEDICINES IN ETHNIC CHINESE POPULATIONS

Patients in Chinese communities base their decisions about using herbalmedicines on family traditions, professional and quasi-professionalrecommendations, and self-medication.

It was once customary for families to have a household repertoire of herbalformulae to treat medical problems and to address life changes (pregnancy,menopause, old age) and the seasons. Some families retain, and especiallyolder patients may continue to follow, these practices.

The professional practice of traditional Chinese medicine is widespreadthroughout the world. Such practice is legalized in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan,Vietnam, Japan, Korea, Europe, and the United States. Practitioners often havea comprehensive grounding in biomedical concepts, including pharmacology.

Quasi-professional recommendations emerge from the traditional herb store,which has been a fixture in China for millennia and is part of any communitywith a substantial Chinese population. These recommendations are typicallybased on a blend of oral tradition, family practice, and quasi-professionalendeavor. The level of expertise ranges widely.

Finally, self-medication typically involves the self-prescription ofprepared medicines available from herb stores, corner groceries, and friends.In these environments, product presentation, labeling, marketing, experience,and recommendations can all influence consumer choice.

CONCERNS ASSOCIATED WITH THE USE OF CHINESE HERBS

Adulteration

Most of the literature on the toxicity of Chinese herbal medicines consistsof case reports describing the effects of using traditional medicinal agentsadulterated with biomedical pharmaceuticals. In the United States, this hassometimes involved pharmaceutical agents that are no longer approved for humanuse. Adulteration with agents such as heavy metals may present the greatestrisk to patients who use Chinese herbs.

Adulteration of prepared medicines imported from China and Taiwan iswidespread. In some instances, these products are legitimate in their countryof origin. In others, an ambitious or unscrupulous manufacturer hasincorporated a pharmaceutical agent to enhance the apparent effects of theprepared herbs. Comparatively harmless examples involve the commonadulteration of the famous herbal remedy for colds Yin Qiao San withacetaminophen. More harmful examples involve herbal medicines adulterated withlarge amounts of cortisone and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs andsold as arthritis remedies. The potential to confuse the consumer is increasedbecause certain stores in American Chinatowns sell biomedical pharmaceuticalsmanufactured in China alongside prepared herbal remedies.

Results of a study of arthritis remedies and analgesics sold in herb storesand Chinese medicine clinics in Taiwan showed that 30% of items sampledcontained drugs,4including acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and phenylbutazone.

In New York, several Chinatown herb stores have sold dangerouslyadulterated substances, including Madam Pearl's Cough Syrup. Thisproduct, which contains codeine, has been an object of regulatory concernsince at least 1988 when it appeared on lists provided by the Department ofHealth Services in California.

Other adulterated preparations found in herb stores, grocery stores, andthrough the mail, include Black Pills, Chui Fong Tou Koo Wan, andCow's Head Tong Sui Pills. Chui Fong Tou Koo Wan is sold for thetreatment of rheumatism and arthritis. It contains, among other ingredients,phenylbutazone, diazepam, and lead.

In 1995, Gertner et al described cases involving five patients fromMinnesota with complications from the use of herbal arthritisremedies.5 In allcases, the pills were found to contain diazepam and mefenamic acid, both ofwhich can have severe side effects.

The public and regulatory agencies, such as the Food and DrugAdministration, are increasingly aware that many illegally imported, butcommonly used, prepared Chinese herbal medicines contain biomedicalpharmaceuticals. Most of these additions are not represented on the productlabel, raising the possibility of overdose or other serious consequences.

Toxicity and adverse effects

Adverse events associated with herbal medicines typically result fromlong-term use at inappropriate dosage levels, the use of certain highly toxicsubstances, and hypersensitivity reactions.

Aconite is probably the most widely used of the highly toxic substanceswithin the Chinese materia medica. The forms of this plant that aresold in herb stores and used in prescriptions are treated with heat, water,and vinegar to degrade the toxic alkaloid and to eliminate any significanttoxicity. Untreated materials are occasionally used, however, and reports oftoxicity have resulted.

Many cases of poisoning with aconite contained in the herbal treatmentschaun wu and cao wu have occurred in China and Hong Kong. Astudy at one Hong Kong hospital between 1989 and 1991 identified eightpatients with signs of poisoning from these substances, including nausea,vomiting, low blood pressure, and ventricularextrasystoles.6

Instances of poisoning are probably underreported, so these cases may bethe tip of the iceberg. The Chinese government was concerned enough to act toimpose controls on prescribing aconite.

The Chinese medicine Jin Bu Huan was implicated in three cases ofoverdose inchildren.7,8The children were hospitalized with life-threatening bradycardia, and centralnervous system and respiratory depression. All recovered after receivingintensive medical care. The product has been formally removed from thecommercial market, although it is still available in New York.Table

Table 2.

Risks and herb-drug interactiosn associated with use of Chinese herbalmedicines

| Medicinal agent | Common name | Plant species | Relevant constituent | Risk/interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma Huang | Ephedra | Ephedra sinica | Ephedrine, pseudoephedrine | Can exacerbate hypertension, palpitations, and dizziness. May interact withmonoamine oxidaseinhibitors,13sympathomimetics, and epinephrine |

| Du Huo | Pubescent angelica | Angelica pubescens | Effect may be associated with furocoumarins | Potentiallyphotosensitizing13 |

| Cao Wu | Aconite | Aconitum carmichaeli, A kuspexoffi | Aconitine | Highly toxic in unprepared form; death can occur as a result of small doses ofunprepared forms |

| Gau Cao | Licorice | Glycrrhiza glabra | Glycyrrhizin, glycrrhetinic acid | Hypokalemia, sodium retention producing hypertension, edema, and headache withprolonged use or a highdose.13 Synergisticeffects with prednisolone,hydrocortisone,12and thiazides. May counteract oralcontraceptives14 |

| Da Huang | Rhubarb | Anthroquinone glycosides, oxalic acid | Irritation of gastrointestinal tract, abdominal cramping, nausea, kidneyirritation; should be avoided in pregnancy | |

| Ren Shen | Ginseng | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Ginseng Abuse Syndrome (controversial syndrome, since may be due toadulterants; syndrome, rarely reported, is considered to include hypertension,anxiety, insomnia); interaction with phenelzine sulfatereported12 |

A well-known case of reported herbal toxicity has come to be known as“Chinese herbs nephropathy.” Seventy women who were patients at aBelgian weight loss clinic from 1991 to 1992 presented with interstitial renalfibrosis and end-stage renalfailure.9,10The Chinese herb Aristolochia was implicated in their renal damage.This species of herb contains aristolochic acid, which is toxic to laboratoryanimals in an extracted and injected form. Debate is ongoing, however, as tothe actual relevance of Aristolochia in nephropathology.

Although Chinese herbal medicines are used commonly, the overall knownincidence of adverse reactions appears relatively low. In an 8-monthprospective study of patients admitted to two general medical wards at onehospital in Hong Kong, only 3 of 1,701 patients (0.2%) were hospitalizedbecause of adverse reactions to Chinese herbalmedicines.11 Thesereactions were life-threatening in two cases (dazao-inducedangioneurotic edema and licorice-induced hypokalemic periodicparalysis).11

Herb-drug interactions

The possibility of herb-drug interactions has beenraised,12 butreports that are directly pertinent to Chinese herbal medicine are scant andoften anecdotal. Instances of well-researched and well-understood interactionsare rare.

The Table provides well-documented examples of commonly used Chinese herbsthat have well-understood side effects or the potential for drug interactions.Given the differences between herbs and single-molecule pharmaceuticalpreparations, dosage level and duration of use are important in assessingrisk. A compound containing licorice, ephedra, or even processed aconitepresents little risk to a patient and is unlikely to interact immediately witha given pharmaceutical. Large quantities, incorrect preparation, or long-termuse of a compound, however, may cause problems to occur.

CARING FOR PATIENTS WHO USE HERBS

Determining whether or not your patient is using Chinese herbal medicinesin raw (decocted) or prepared forms requires sensitivity. Patients may bedisinclined to provide this information even when asked directly. Making anopen-ended inquiry couched in supportive terms is helpful. You may prefaceyour inquiry with an encouraging generalization, such as: “I understandthat in China there are many herbs that can be used to treat diseases. Some ofthem can be very helpful. Are there any herbs that you like to use? Are youtaking any herbs or other medicines now?”

How to advise the patient concerning herb use is a matter of professionaljudgment. In the best case, it will be possible to communicate with theprescribing herbalist and explore any issues of concern. Many, but not all,practitioners of Chinese herbal medicine can address some of these issues. Ifthe patient is using prepared medicines, you may be able to gain access to thepackaging to assess the content, although the information provided is notalways reliable.

Many clinicians choose the simple course and advise the patient todiscontinue or moderate its use. Although this advice may seem to be the bestcourse of action, it may reduce the quality of future communication with thepatient or with other patients. Consequently, attempting to gain moreinformation and informing the patient about the basis for your advice isimportant. Often, patients can help you learn more about why they are usingherbs.

The resources listed in box2 offer a first step in becoming more acquainted with aspects ofChinese herbal medicine.

Box 2.

Resources for health professionals on Chinese herbal medicine

| Text resources |

|

| Internet resources |

|

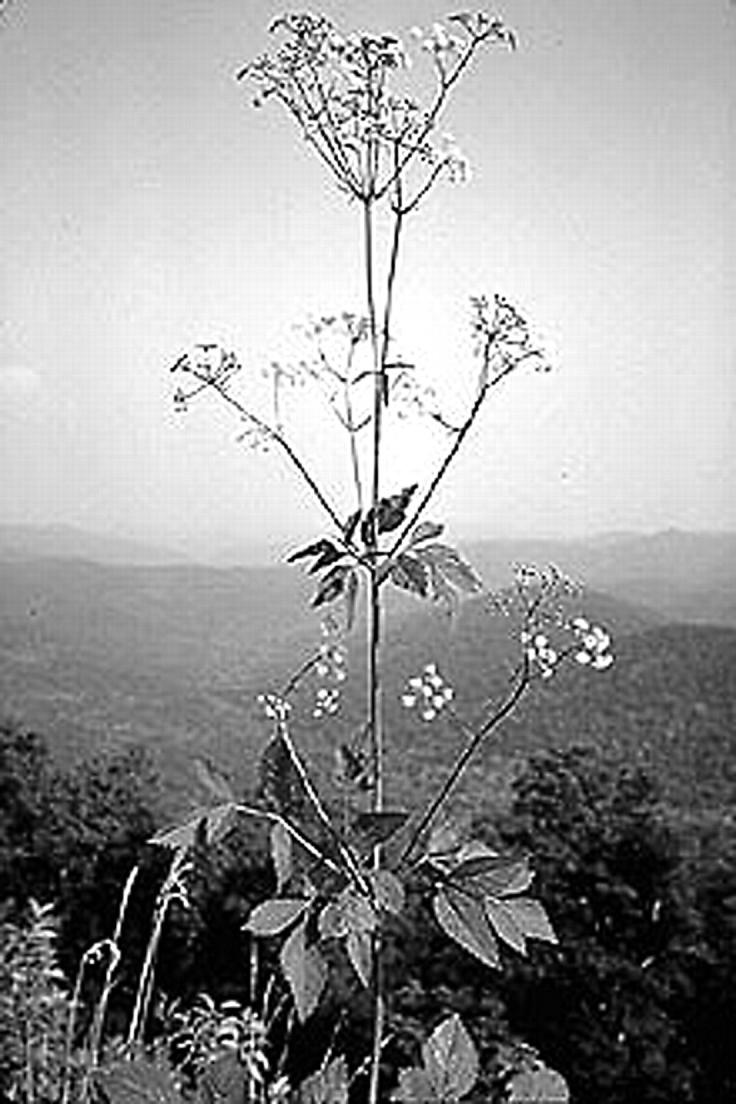

Figure 1.

William S Justice/PLANTS/NRCS/USDA

Licorice or compounds containing licorice have been associated with adverseside effects in some patients

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Bensky D, Gamble A. Chinese Herbal Medicine MateriaMedica. Seattle: Eastland Press; 1993:5.

- 2.Zhang E, Jidong Z, Zhigang L, Clinic of Traditional ChineseMedicine (I), trans. Weixin J, Shushan S, Xiaoyue G. In A PracticalEnglish-Chinese Library of Traditional Chinese Medicine, E Zhang,ed. Shanghai: Publishing House of Shanghai; 1990:212.

- 3.Wiseman N, Ye F. A Practical Dictionary of ChineseMedicine. Brookline, MA: Paradigm; 1998:123.

- 4.Dharmananda S. Tiptoeing Through the Chinese MedicalMine Field. Start Group. Portland: Institute for TraditionalMedicine; 1994.

- 5.Gertner E, Marshall PS, Filandrinos D, Potek AS, Smith TM.Complications resulting from the use of Chinese herbal medications containingundeclared prescription drugs. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:614-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan TY, Tomlinson B, Critchley JA. Aconitine poisoning followingthe ingestion of Chinese herbal medicines: a report of eight cases.Aust N Z J Med 1993;23:268-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin bu huan toxicity in children—Colorado, 1993.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1993;42:633-636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration Center for Food Safety and AppliedNutrition 1993. Illnesses and Injuries Associated With the Use of SelectedDietary Supplements. Available atwww.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/ds-ill.html.Accessed March 22, 2002.

- 9.Depierreux M, Van-Damme B, Vanden-Houte K, Vanherweghem JL.Pathologic aspects of a newly described nephropathy related to the prolongeduse of Chinese herbs. Am J Kidney Dis 1994;24:172-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanherweghem JL, Depierreux M, Tielemans C, et al. Rapidlyprogressive interstitial fibrosis in young women: association with slimmingregimen including Chinese herbs. Lancet 1993;341:387-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan TYK, Chan AYW, Critchley JA. Hospital admissions due toadverse reactions to Chinese herbal medicines. J Trop MedHyg 1992;95:296-298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fugh-Berman A. Herb-drug interactions.Lancet 2000;355:134-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. BotanicalSafety Handbook. Boston: CRC Press;1997.

- 14.Mills S, Bone K. Principles and Practice ofPhytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. New York: ChurchillLivingstone; 2000: 474.