Abstract

Introduction:

Lymphangiomatosis is a rare abnormal proliferation of lymphatic vessels involving multiple organs like the brain, lung, heart, spleen, liver, and bones. Lymphangiomas constitute 5.6% of all benign tumors in infancy and adulthood.

Case presentation:

We report a case of a young lady who presented with constitutional symptoms and progressive dyspnea. Her medical history is significant for muco-cutaneous albinism, diffuse hemangiomas of the bone and viscera, and consumptive coagulopathy status post-splenectomy. After initial investigations, she was found to have right-sided pleural effusion. Pleural fluid analysis indicated chylothorax. She had multiple drainages of the pleural fluid done, and afterward, ligation of the right thoracic duct was performed with a trial of sirolimus, which improved her chylothorax.

Clinical discussion:

Several case reports have reported positive outcomes with sirolimus in the treatment of lymphangiomatosis. However, larger controlled studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusion:

Sirolimus is promising as a medical treatment for diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis.

Keywords: chylothorax, lymphangiomatosis, lymphatic vessels, pleural fluid, sirolimus

Introduction

Highlight

Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis (DPL) is a rare proliferation of the lymphatic vessels.

DPL may present with severe pleural effusion.

Treatment with sirolimus can effectively relieve the DPL-related symptoms.

Diffuse lymphangiomatosis is a very uncommon lymphatic disorder. It develops through the lymphatic system, affecting different parts of the human body that contain lymph nodes. It is considered fatal amongst newborns and children because of its aggressive growing compression of the bone1,2. Lymphangiomas can be localized tumors that affect a single organ or multiple organs. It is caused by lymphatic development abnormalities as it proliferates, anastomoses the lymphatic vessels, and makes the tumor uncontrollable. Lymphangiomas commonly affect the lungs, pleura, brain, thorax, back, and neck. When the lungs are involved, they are classified as diffused pulmonary lymphangiomatosis (DPL) and attributed to the organ system with the most deaths.

The survival rate of DPL is low, especially in children younger than 16 years3. The diagnosis of lymphangiomatosis is challenging owing to the rarity of the disease and the nonspecific presentation, as it is commonly misdiagnosed as different types of respiratory disorders; however, lung function tests can be helpful in determining the diagnosis4. The treatment of lymphangiomatosis is not yet standardized and is usually based on case reports in the literature, the patient’s presenting symptoms, and pathology2,5. Therefore, in this article, we report the case of an 18-year-old female with lymphangiomatosis who was successfully treated with sirolimus. This manuscript was reported according to the CARE criteria6.

Case presentation

An 18-year-old female was presented to the emergency department with a one-day history of fever, vomiting, and progressive shortness of breath. Her past medical history included muco-cutaneous albinism, diffuse hemangioma of the bone and viscera, consumptive coagulopathy status post-splenectomy 10 years ago, and a history of meningitis in the past. She was non-compliant with her penicillin V prophylaxis therapy. On examination, she was vitally stable on room air, and albinism was noted all over the skin. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy and normal audible first and second heart sounds with no added mummers. Chest examination showed decreased chest expansion over the right side with decreased breath sounds, decreased vocal resonance, and dull percussion. Abdomen examination was only remarkable for the splenectomy scar, and nervous system examination was unremarkable. Initial blood results revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 20.31×109/l. Coagulation, renal, and liver profiles were normal.

Her chest X-ray at presentation showed right-sided pleural effusion and multiple lytic lesions with expansion of the ribs and clavicle, as well as the scapula (Fig. 1). Subsequently, the patient underwent ultrasound-guided diagnostic and therapeutic pleural tapping with pigtail insertion for pleural fluid drainage. The results of the pleural fluid analysis can be seen in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray revealing right-sided pleural effusion and multiple lytic lesions of the ribs and clavicle.

Table 1.

Results of the pleural fluid analysis

| Pleural fluid analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Milky | PH | 7.6 |

| White blood cell count | 3250 | Lymphocytes | 57% |

| Red blood cell count | 54 000 | Adenosine deaminase | 6.7 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 136 | Albumin | 22 |

| Proteins | 37 | Triglyceride | >3.6 |

| Glucose | 5.7 | Cholesterol | 1.5 |

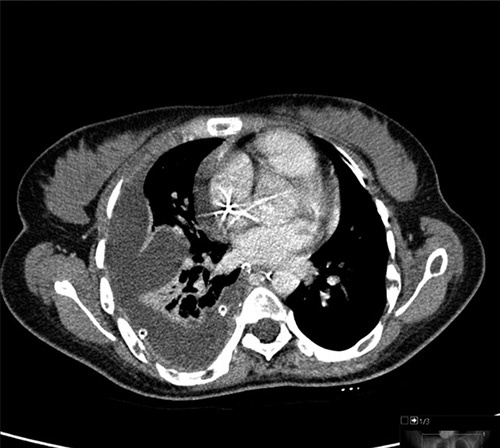

A high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a large right-sided pleural effusion with significant collapse of the right lung (Fig. 2). Mildly enlarged lymph nodes were also seen in the mediastinum and the right axilla. Due to the presence of lymph nodes noted in the CT scan, suspicion of malignancy was raised. A free needle aspiration was performed; however, the results were inconclusive. The patient did not wish to undergo a biopsy of the lesion. Therefore, a positive emission tomography-CT was done and was negative for significant uptake. Pleural fluid was continuously drained from the chest pigtail. The patient was then managed conservatively with octreotide and a low-lipid diet. However, the patient did not improve, and the pigtail was draining between 1000 and 1500 ml of pleural fluid daily.

Figure 2.

Axial computed tomography scan of the chest demonstrating severe right-sided pleural effusion and right lung collapse.

A multidisciplinary team meeting was arranged, and it was decided to conduct a lymphogram study, which confirmed systemic malformation of lymphatic vessels. Accordingly, the patient was started on sirolimus 3 mg orally per day, which was tolerated well, apart from the persistent tachycardia. The patient was also placed on total parenteral nutrition for 4 weeks. The patient had an echocardiogram, demonstrating a large mass in the right atrium attached to the anterolateral wall, measuring 14 mm×11 mm and showing some independent mobility; the mass was suspected to be a potential thrombus. These findings were then confirmed with a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging scan, and the patient was started on enoxaparin. Her tachycardia improved afterward, and a follow-up chest X-ray showed improvement in her pleural effusion; however, persistent small lobulated effusion and shortness of breath were noted.

The patient was seen by the cardiothoracic team, and thoracoscopic evacuation of pleural fluid and thoracic duct clipping was performed to relieve the remainder of the pleural effusion. She then showed almost complete resolution of her pleural effusion and was continued on sirolimus and discharged home with a dermatology follow-up to monitor the treatment.

Discussion

Lymphangiomas are benign, the congenital proliferation of lymphatic vessels that can occur in any area of the body containing lymphatics7. Upon expanding into the thorax, lymphangiomas may cause symptoms via a field effect, as witnessed in DPL. DPL often presents with vague symptoms and nonspecific radiological findings; hence, the diagnosis remains a challenge8. Progressive DPL may lead to chylous effusions and pulmonary damage, as seen in our patient8. CT mainly reveals attenuation of mediastinal fat with thickening of interlobular septa and bronchovascular bundles8. Furthermore, most patients have patchy areas of ground-glass opacities9.

There are no standardized treatment guidelines for DPL, owing to its rarity. However, various pharmacological therapies have been tried, including bevacizumab, sildenafil, thalidomide, propranolol, and sirolimus10. Reports utilizing sirolimus in DPL treatment are extremely limited. In Table 2, we have summarized several case reports that have explored the use of sirolimus in the treatment of DPL, highlighting the study design and primary authors. Dimiene et al.10 described the case of a 26-year-old man with progressive dyspnea, hemoptysis, and night sweats due to underlying DPL. The authors reported successful treatment with sirolimus and propranolol, which was used to control tachycardia and support treatment by reducing vascular endothelial growth factor levels. Similarly, Gurskytė et al.8 reported the case of a 27-year-old man who presented with dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis due to DPL. At 21 months of sirolimus treatment, their patient reported decreased coughing, and a CT scan revealed decreased interstitial thickening.

Table 2.

Summary of case reports on the use of sirolimus in the treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis.

| Number | Title | Authors (et al.) and year of publication | Country | Age and sex of the patient | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with pleural and pericardial involvement. Pediatric case report | Moreno et al.11, June 2021 | Italy | 22-month-old female | Case Report |

| 2 | Diagnosis and treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangioma in children: a case report | Sun et al.12, April 2023 | China | 8-year-old male | Case Report |

| 3 | The successful management of diffuse lymphangiomatosis using sirolimus: a case report | Reinglas et al.13, August 2011 | Canada | 4-month-old male | Case Report |

| 4 | Effective initial treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with sirolimus and propranolol: a case report | Dimiene et al.10, December 2021 | Lithuania | 26-year-old male | Case Report |

| 5 | Successful treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with sirolimus | Gurskytė et al.8, 2020 | Lithuania | 27-year-old male | Case Report |

Note: The search strategy was conducted on PubMed, Google Scholar, and Embase. The search strategy was as follows: (“Lymphangiomatosis” OR “Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis” OR “DPL”) AND (“Sirolimus” OR “Rapamycin”) AND (“Treatment” OR “Therapy”) AND (“Pleural effusion” OR “Chylothorax”) AND (“Case report” OR “Case series”).

The major limitation of the present case is the lack of confirmatory pathological findings. Our diagnosis largely relies on the radiological findings of the patient. Additionally, the diagnosis is supported by the rapid response of the patient to sirolimus. Although the incisions needed for DPL are relatively small, the resulting injury often exacerbates the existing chylothorax14.

Conclusion

In this article, we reported the case of a patient with pleural effusion due to underlying lymphangiomatosis. Treatment of lymphangiomatosis is not yet standardized and is widely based on case reports and personal experience. However, several reports in the literature have demonstrated positive outcomes with sirolimus. In the present study, sirolimus effectively reduced lymphatic proliferation and relieved the patient of her pleural effusion. Larger studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Ethics approval

Patient consent was provided for the publication of this manuscript and accompanying images.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Sources of funding

This study did not receive funding from any source.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the research and/or preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

None.

Guarantor

Dr Muhammad Riazuddin.

Data availability statement

All data analyzed are available in the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 5 October 2023

Contributor Information

Muhammad Riazuddin, Email: mriazuddin@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Noha I. Farouk, Email: noha.ot12@gmail.com.

Saad S. Ali, Email: saaali@alfaisal.edu.

Muhammad I. Butt, Email: mimranbutt@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Tarek Z. Arabi, Email: tarabi@alfaisal.edu;arabi.tarek@gmail.com.

Belal N. Sabbah, Email: bsabbah@alfaisal.edu.

Maha S. Ali, Email: msali@alfaisal.edu.

Khaled Alkattan, Email: kkattan@alfaisal.edu.

References

- 1.Faul JL, Berry GJ, Colby TV, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomas, lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161(3 Pt 1):1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tazelaar HD, Kerr D, Yousem SA, et al. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Hum Pathol 1993;24:1313–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukahori S, Tsuru T, Asagiri K, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomatosis with massive chylothorax after a tumor biopsy and with disseminated intravenous coagulation – lymphoscintigraphy, an alternative minimally invasive imaging technique: report of a case. Surg Today 2011;41:978–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Jin H, Wang Y, et al. A case of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with unilateral lung invasion. Oxf Med Case Reports 2015;2015:346–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hangul M, Kose M, Ozcan A, et al. Propranolol treatment for chylothorax due to diffuse lymphangiomatosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019;66:e27592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. the CARE Group . The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. J Med Case Rep 2013;7:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadakia KC, Patel SM, Yi ES, et al. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Can Respir J 2013;20:52–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurskytė V, Zeleckienė I, Maskoliūnaitė V, et al. Successful treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with sirolimus. Respir Med Case Rep 2020;29:101014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swensen SJ, Hartman TE, Mayo JR, et al. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1995;19:348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimiene I, Bieksiene K, Zaveckiene J, et al. Effective initial treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with sirolimus and propranolol: a case report. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57:1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno RP, Hernández Y, Garrido P, et al. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with pleural and pericardial involvement. Pediatric case report. Arch Argent Pediatr 2021;119:e264–e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun X, Lu C, Huang Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangioma in children: a case report. Exp Ther Med 2023;25:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinglas J, Ramphal R, Bromwich M. The successful management of diffuse lymphangiomatosis using sirolimus: a case report. Laryngoscope 2011;121:1851–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang X, Huang Z, Zeng Y, et al. Lymphangiomatosis involving the pulmonary and extrapulmonary lymph nodes and surrounding soft tissue. Medicine 2017;96:e9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed are available in the manuscript.