Abstract

The β-Oxidation pathway, normally involved in the catabolism of fatty acids, can be functionally made to act as a fermentative, iterative, elongation pathway when driven by the activity of a trans-enoyl-CoA reductase. The terminal acyl-CoA reduction to alcohol can occur on substrates with varied chain lengths, leading to a broad distribution of fermentation products in vivo. Tight control of the average chain length and product profile is desirable as chain length greatly influences molecular properties and commercial value. Lacking a termination enzyme with a narrow chain length preference, we sought alternative factors that could influence the product profile and pathway flux in the iterative pathway. In this study, we reconstituted the reversed β-oxidation (R-βox) pathway in vitro with a purified tri-functional complex (FadBA) responsible for the thiolase, enoyl-CoA hydratase and hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activities, a trans-enoyl-CoA reductase (TER), and an acyl-CoA reductase (ACR). Using this system, we determined the rate limiting step of the elongation cycle and demonstrated that by controlling the ratio of these three enzymes and the ratio of NADH and NADPH, we can influence the average chain length of the alcohol product profile.

Keywords: β-Oxidation pathway, Fatty alcohols, metabolic engineering, Enzyme kinetics, thiolase

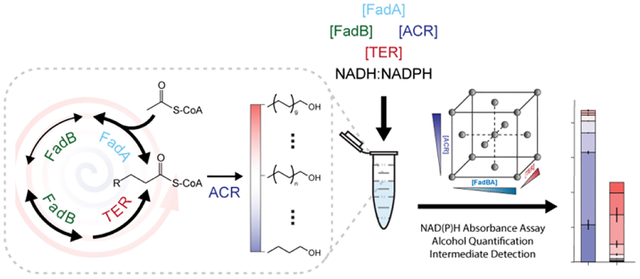

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Cellular metabolism orchestrates catabolic and anabolic processes to deconstruct environmental molecules into a core set of precursor metabolites which are used to synthesize the complex molecular building blocks of a cell. By funneling into and then expanding out from these central metabolites, a wide range of chemistries can be performed with a limited set of enzymes. To form the high molecular weight cellular building blocks from these precursors (e.g., fatty acids, nucleotides, isoprenoids and amino acids), anabolism must form carbon-carbon bonds. Interestingly, several of these molecules are synthesized via iterative elongation cycles that add either one (iterative 2-ketoacid elongation1), two (fatty acid2, polyketide3), or five (isoprenoid4,5) carbons through acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, or prenyl-pyrophosphate building blocks. Enzymes of these pathways have evolved to constrain the end product of this iterative synthesis to products of the required length, but little is known about how the fundamental kinetics of these enzymes contribute to the product size distribution. This knowledge gap is important to metabolic engineers who want to synthesize specific products, often not found produced in nature, using these iterative carbon elongation pathways without depending on the evolutionary process.

In this study, we examined in vitro how kinetic factors influence the fatty alcohol product distribution produced by an iterative, thiolase mediated, +2 carbon elongation pathway. The hallmark of this pathway is the reversible thiolase-mediated non-decarboxylative Claisen condensation of acetyl-CoA with an acyl-CoA thioester molecule6–8. The reverse reaction catalyzed by this enzyme (i.e., cleavage of an acetate unit from β-ketoacyl-CoA) is commonly associated with the β-oxidation of normal fatty acids that produces acetyl-CoA and NADH for energy generation. Natural examples of thiolase-mediated elongation pathways include the production of C4 - C6 acid and alcohol molecules by solventogenic Clostridium species9,10, and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biosynthesis11–13. In addition to engineering efforts focused on these short-chain producing natural pathways14–17, engineering strategies have been developed to functionally reverse the β-oxidation pathway for longer chain-lengths18,19. The combination of enzymes from these different pathways, often collectively referred to as R-βox in the metabolic engineering community, unlocks the potential for the production of a wide range of aliphatic compounds (e.g., fatty acids19–23, alcohols20,24,25, β-hydroxy-carboxylic acids14,23,26) classified as oleochemicals. The inherent properties and commercial value of oleochemicals is dependent on their functional groups and, chain length. It is therefore critical to determine which enzymatic factors are important to controlling the limits of the iterative carbon chain elongation cycle.

Compared to the highly analogous fatty acid biosynthesis pathway, where the extending unit malonyl-CoA is synthesized via an ATP-dependent carboxylation of acetyl-CoA, the R-βox pathway directly uses acetyl-CoA and requires no ATP, resulting in higher theoretical yields27. This ATP efficiency allows this pathway to be utilized in a fermentative manner when producing alcohols as the final product, serving as a balanced electron sink for substrate level phosphorylation in anaerobic growth25. Additionally, because the pathway is orthogonal to cell envelope synthesis, upper limits to the elongation cycle can be implemented without detriment to the cell’s ability to grow. These advantages make R-βox attractive for oleochemical production in microorganisms. Significant progress has been made in demonstrating the potential to expand product classes and incorporate additional functionalization of the carbon chain through α- and ω- substitutions28. The main remaining challenge that must now be overcome in the development of the R-βox pathway is that of achieving highly specific product chain-lengths at high titers. With the exception of pathways limited to a single acyl-CoA condensation (e.g., butanol15, butyrate19, hydroxybutyrate14, and adipic acid29), few examples of iteratively elongating R-βox engineered strains exist that display high degrees of chain-length specificity. Identification or engineering of chain-length specific, CoA active, terminal enzymes severely lags behind efforts surrounding the ACP dependent fatty acid pathway; and unfortunately, thioesterases engineered for use with the fatty acid biosynthesis (FAB) pathway show little activity on CoA substrates23. While notable exceptions exist that achieved > 50% specificity for a single molecule21,23,30, new strategies must be developed or enzymes engineered for controlling chain-length.

We hypothesize that chain-length control might be achievable through precise control of the flux ratio between the elongation cycle and termination. In fact, a recent study by Main et al. on FAB pathway has demonstrated that changes in enzyme concentrations could control the length of fatty acid products31. To explore the impacts that enzyme and cofactor ratios have on the R-βox pathway, we chose to reconstitute an alcohol producing R-βox pathway using enzyme homologs that yielded the highest alcohol titer in previous study by Mehrer et al.25. In this pathway, the core elongation cycle consists of the tri-functional FadBA enzyme complex from Vibrio fischeri (vfFadBA) catalyzing the thiolase condensation of acetyl-CoA and acyl-CoA, β-ketoacyl-CoA reductase, and hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydratase steps, and the trans-enoyl-CoA reductase from Treponema denticola (tdTER). Elongation is terminated by a broadly active, NADPH requiring, acyl-CoA reductase from Marinobacter aquaeoli (maACR) that reduces acyl-CoAs to alcohols through an aldehyde intermediate. An overview of the pathway is shown in Figure 1. Notably, engineered strains expressing these enzymes exhibited a broad product profile, centered around medium chain-lengths, allowing investigation of how product profiles shift in a more continuous manner compared to what might be observable with a pathway restricted to fewer, shorter chain products.

Figure 1.

Reversed β-Oxidation Pathway Overview and in vitro Assay Design.

(Left) Enzymes and metabolites of the reconstituted alcohol producing reversed β-oxidation (R-βox) pathway. The R-βox pathway starts with the condensation of acetyl-CoA and acyl-CoA. The resulting product, β-ketoacyl-CoA, was then reduced, dehydrated, and reduced again to yield an elongated acyl-CoA. The acyl-CoA can either undergo another elongation cycle or terminated via acyl-CoA reductase (ACR) to form fatty alcohols of different chain-lengths. (Right) The R-βox pathway was reconstituted in vitro via enzyme purification to allow direct measurement of NAD(P)H consumption and alcohol production. Reactions were set up as shown with the ordered addition of reaction buffer, NADH, NADPH, vfFadBA, tdTER, and maACR in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and initiated by the addition of acetyl-CoA. Three 100 μL aliquots of each 1 mL reaction were then split into 96-well plate for NAD(P)H absorbance measurement at 30°C. After one hour, the reaction was extracted using ethyl-acetate and quantified via GC-MS. Data obtained from NAD(P)H assays were used to calculate NAD(P)H initial rate and NAD(P)H consumption at 1 hour. Molar fraction of alcohol products and acetyl-CoA equivalents were calculated based on data from GC-MS. Data on the rightmost graph was generated from one reaction condition in the DOE and is used as a representative output form of the study. Abbreviations: vfFadBA, tri-functional enzyme complex from Vibrio fischeri; tdTER, trans-enoyl-CoA reductase from Treponema denticola; maACR, acyl-CoA reductase from Marinobacter aquaeoli.

Results and Discussion

Reconstitution of Fatty Alcohol Producing R-βox Pathway in vitro

All enzymes were purified via N-terminal affinity tag chromatography (see methods for full details) and confirmed for purity via SDS-PAGE (Figure S1). The vfFadBA complex was co-purified, as prior reports indicated a loss of thiolase activity when E. coli FadA was purified individually19,32. In addition to the core enzymes, we also separately purified the vfFadB subunit, which maintains activity outside the complex, a co-purified vfFadBA complex with a point inactivation of thiolase activity (vfFadBA*), and an independent thiolase from Cupriavidus necator (BktB). To prevent possible complexing of the His-tagged vfFadB with non-cognate E. coli FadA, these purified enzymes were produced using a ΔfadBA BL21(DE3) strain. In several previous studies, including kinetic characterization and the strains upon which we have modeled our in vitro pathway, maACR was expressed and characterized with an N-terminal Maltose-Binding Protein fusion25,33. To allow for comparison of our results to these studies, we also left this fusion intact after purification.

With these purified enzymes, we were able to reconstitute the pathway in vitro, producing alcohols of varying chain lengths from acetyl-CoA. Reconstituted pathway reaction progress was monitored via NAD(P)H absorbance at 340 nm, and product alcohols were extracted at one hour for quantification via GC-MS. Absorbance assay data was used to calculate both initial NAD(P)H consumption rates and total NAD(P)H consumption at one hour. Alcohol concentrations were used to determine product profiles, and to calculate the stoichiometric NAD(P)H and acetyl-CoA necessary to produce the quantified alcohols (e.g., one octanol requires eight NAD(P)H and four acetyl-CoA). An overview of the experimental setup and data collection is shown in Figure 1.

Control reactions leaving out one of the three enzyme components confirmed that all enzymes were necessary to produce alcohols (Figure S2). Given the predicted NADH preference of vfFadBA based on cofactor prediction algorithms34, the experimentally determined NADH preference for tdTER35, and the reported strict requirement for NADPH of maACR33, we were surprised to find that mixtures supplemented with only NADH or only NADPH were both able to produce alcohols. That said, the initial rates of reaction, total reaction progress, and alcohol product chain-length distribution were all significantly affected by which cofactor was included (Figure S3).

Factors influencing in vitro flux and product profile

To characterize how the concentration of each enzyme and the NADH:NADPH cofactor ratio affect pathway flux and product profile, we conducted a face-centered central composite experiment. In a series of exploratory fractional factorial experiments, we found that while inclusion of 10 nM of either tdTER or maACR yielded measurable alcohols, when only 50 nM of vfFadBA was included, alcohol production dropped near the limit of detection. Factor levels for the design of experiment (DOE) were therefore chosen as 200 nM to 1,000 nM for vfFadBA, and 10 to 500 nM for both tdTER and maACR. The NADH fraction ranged from 10 to 90% of the total 2.5 mM cofactor concentration – the maximum concentration permitted by the linear range of the spectrophotometer. Each set of reaction conditions were run in quadruplicate, with additional replicates (total n=8) run for the central condition (Figure 2). Trials were run in a randomized order across a total of 8 batches. NAD(P)H absorbance curves for all reactions are shown in Figure S4 and summary results for the full dataset are shown in Figure S5. For ease of comparison, subsets of the results are also presented sorted into paired conditions, such that only the factor of interest is changing (Figures S6–S9). Results were fit to empirical models (given in Tables S3–S7) using JMP Pro 15 (SAS Institute) to determine what factors, or binary factor interactions had significant influence on initial rates of NAD(P)H consumption, total NAD(P)H consumed at one-hour, total acetyl-CoA equivalents (or NAD(P)H equivalents) of alcohol products at one hour, and product chain length profiles.

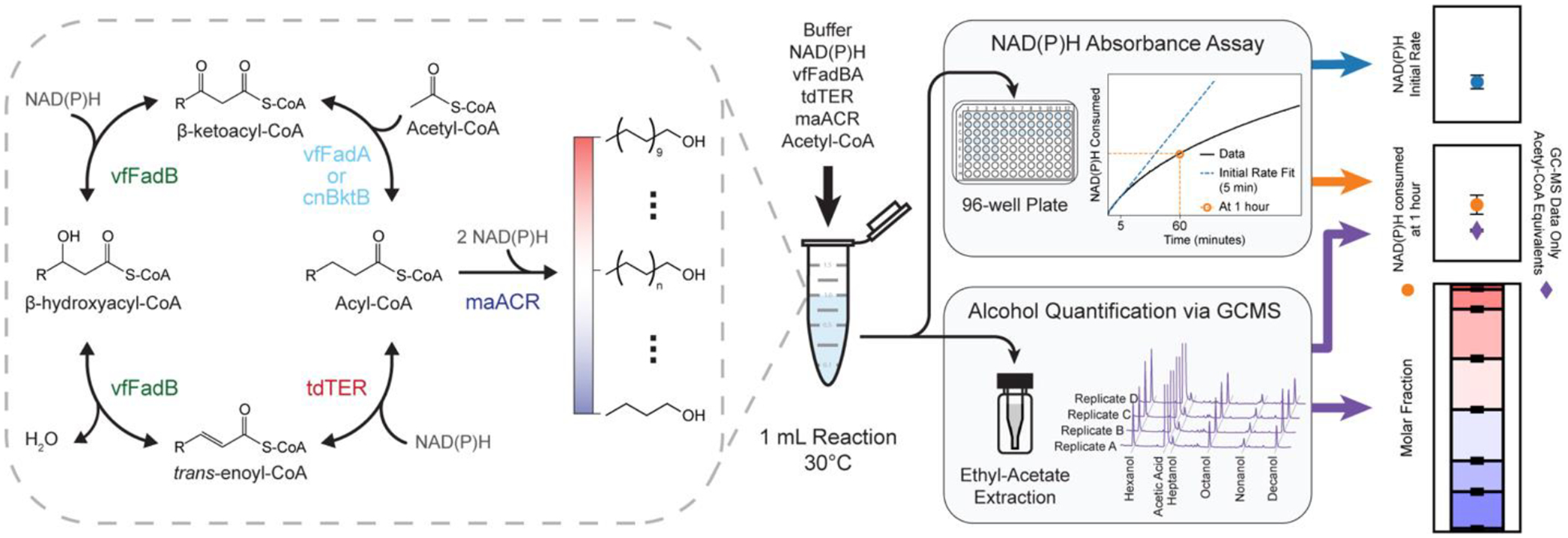

Figure 2.

Overview of Face-Centered Central Composite Experimental Design and Results.

(Left) A representative graphical illustration of a 3-dimensional face centered (a=1) central composite design, with conditions shown as gray spheres. Factor levels used in our 4-dimensional design are shown below. (Top-Right) Initial pathway flux is most heavily impacted by the concentration of vfFadBA. Comparison of the initial NAD(P)H consumption rates, where vfFadBA concentration is the only factor changing in each pair or set (separated by vertical gray lines). (Bottom-Right) maACR concentration heavily influences alcohol profiles. Pairwise comparison of reaction conditions in which maACR concentration is the only factor changing in each pair or set (separated by vertical gray lines). Reactions were carried out in quadruplicate (n=4) with additional replicates (total n=8) run at the central condition. Absorbance assay for each reaction was carried out in technical triplicates (n=3). Values presented for absorbance assay represents the mean and standard deviation calculated from the mean value of each set of technical replicates, adjusted to account for background auto-oxidation of NAD(P)H. Stacked bars represent molar fractions, calculated as the average molar concentrations across all present chain-lengths, corrected for propagated error of the total molar concentration. Statistical significance shown in the top-right plot are the result of a Student’s t-test between paired conditions (* p< 0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001).

Initial Rate of NAD(P)H Consumption

The initial rate of NAD(P)H consumption was most significantly controlled by the concentration of vfFadBA (Table S3, Figure S6). The observed initial rate is not accounted for by only the initial steps carried out by vfFadBA (i.e., the NAD(P)H-consuming reduction of acetoacetyl-CoA). When tdTER is not present, the initial NAD(P)H consumption rate is reduced compared to reactions with both vfFadBA and tdTER (Figure S2). However, increased concentrations of tdTER does not lead to increased initial NAD(P)H consumption rate (Figure S7). This suggests that one of the reactions catalyzed by vfFadBA is rate limiting in the R-βox elongation cycle.

Total NAD(P)H Consumption

Total NAD(P)H consumption at one hour was heavily influenced by the NADH fraction (Table S4, Figure S9). At low NADH fractions, a significant reduction of reaction progress is observed, suggesting that NADH concentration can become severely limiting. Investigation of NAD(P)H consumption in conditions with high vfFadBA concentration and low NADH concentration reveals that NAD(P)H is rapidly consumed until the total consumption reached approximately 0.25 mM, at which point the reaction slows or plateaus entirely (Figure S4). We interpret this as complete consumption of the 10% NADH fraction of the 2.5 mM total cofactor. Consistent with vfFadBA control of initial rates, when NADH is not at limiting concentrations (i.e., reactions with an NADH fraction of 0.5 or 0.9), vfFadBA exhibits influence over the total NAD(P)H consumption. Under these reaction conditions, decreases in vfFadBA concentration results in statistically significant decreases in the total NAD(P)H consumption in all but one case (Figure S6).

Acetyl-CoA Conversion to Alcohols

In contrast to the total NAD(P)H consumption at one hour, maACR shows significant influence over the total conversion of acetyl-CoA (or NAD(P)H) to alcohols. maACR concentration was the most influential parameter (Table S5) and shows significant effects across all paired conditions (Figure S8). Consistent with the absorbance assay data, a low NADH fraction decreases acetyl-CoA conversion to product alcohols when vfFadBA concentration is sufficiently high (Figure S9). Similarly, vfFadBA shows statistically significant effects in the same paired conditions in which it affected the absorbance assay results, i.e., when NADH concentration is not limiting (Figure S6).

The absorbance assay captures net pathway activity but cannot distinguish between increased formation of alcohols and increased concentrations of pathway intermediates. A direct comparison of the absorbance assay and GC-MS equivalent NAD(P)H consumption shows a significant portion of the total NAD(P)H consumed is not accounted for as alcohols when maACR is low or NADH fractions are high (Figure S10). This NAD(P)H-consumption gap indicates that a significant build-up of elongation cycle intermediates may be occurring under these conditions.

Alcohol Product Profile

In the conditions carried out above, we found that the reconstituted pathway was capable of producing alcohols ranging from C4 to C20, with average molar chain-lengths between 5.0 and 15.2. Terminating enzyme maACR showed the strongest effect with increased concentrations resulting in significant reductions of average chain-lengths (Table S6, Figure S8). Increased concentration of the enzymes of the elongation cycle led to mild elongation of the average chain-length (Figures S6 and S7). NADH fraction followed the trends corresponding to enzyme cofactor preference, with increased NADPH concentrations resulting in shorter products (Figure S9). This effect was further exacerbated in conditions where NADH becomes limiting.

Product formation at varying chain-lengths is a direct competition between elongation or termination of the acyl-CoA metabolite. We hypothesized that the average chain-length then would be a function of the concentration ratio of enzymes controlling elongation and termination flux. We found that increasing average chain-lengths corresponds to a logarithmically increasing concentration ratio of vfFadBA and maACR (Figure S11), though at high enzyme ratios, low NADH concentrations become limiting. The standard deviation of the product-profile follows trends in the molar average chain-length. Standard deviations are low at low average chain-lengths, increasing to a plateau as longer chain-lengths are reached (Figure S12). At the shortest average chain-lengths the product profiles are skewed, with butanol representing a significant portion of the product profile. We expect a similar skew towards product specificity at upper limits of chain-elongation may be possible. However, at the maximum average chain-lengths observed in this experiment we do not observe such a trend.

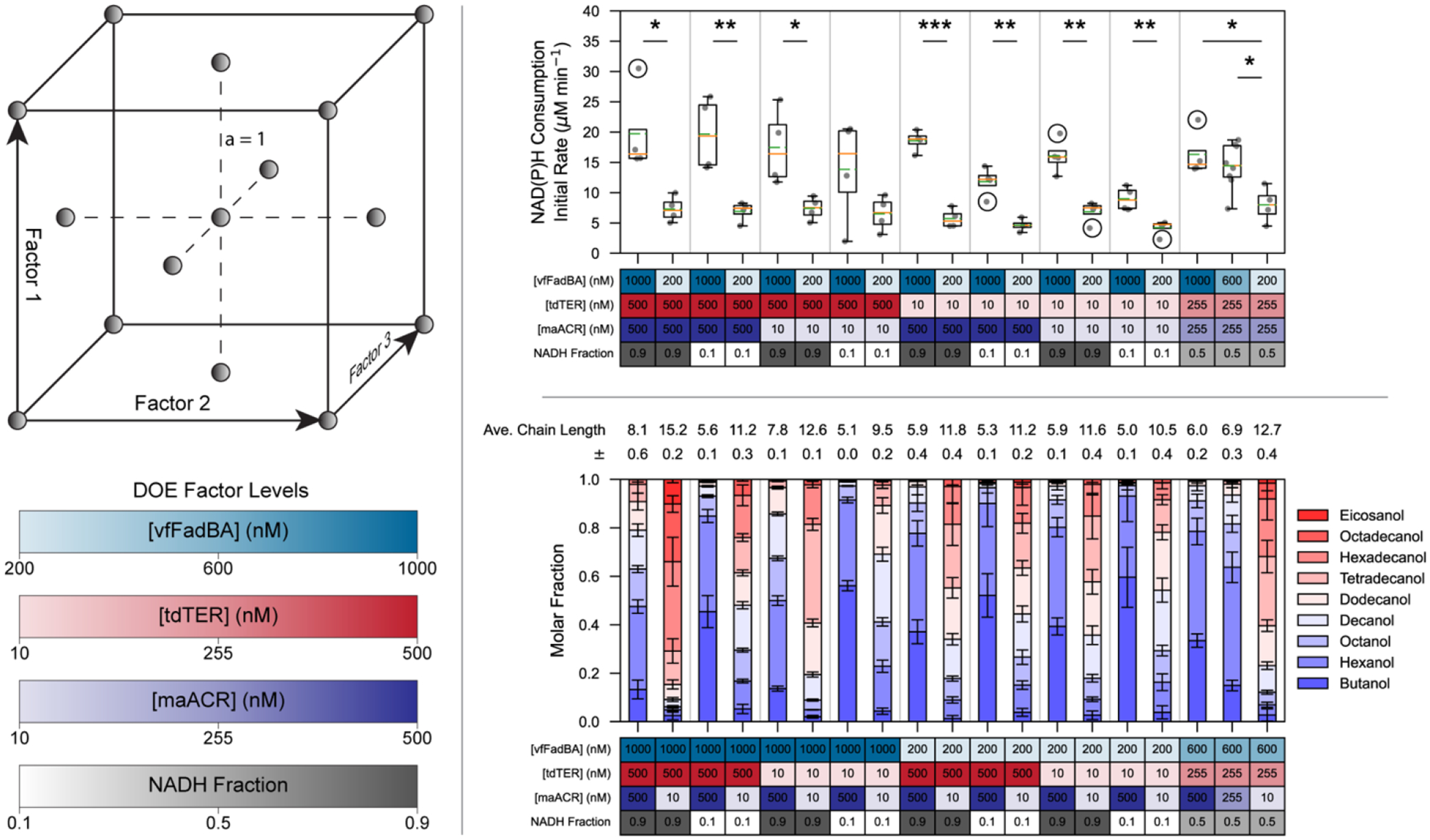

β-ketoacyl-CoA Reduction is the Rate Limiting Step Catalyzed by vfFadBA

To identify which subunit of the trifunctional vfFadBA complex catalyzes the rate limiting step, we ran a series of in vitro reactions supplementing additional vfFadBA, vfFadB, or BktB into a baseline reaction containing 200 nM vfFadBA (Figure 3, vfFadB and BktB control reactions shown in Figure S13). Due to the loss of vfFadA activity observed in previous studies19,32 we introduced BktB, an independent thiolase with activity limited to a maximum C10 chain length. Contrary to our initial hypothesis that thiolase activity was rate limiting, the addition of BktB did not result in increases to the initial rate. Instead, it was when additional vfFadB was included in the reaction that the initial rate increased. With only 200 nM of the FadA subunit thiolase, total vfFadB concentrations of 600 nM or 1000 nM resulted in initial rates and total activity comparable to reactions with the full complex at the same concentration.

Figure 3.

Determination of Rate Limiting vfFadBA Subunit.

Reactions with a base level of 200 nM vfFadBA were supplemented with an additional 400 nM or 800 nM of either vfFadBA, BktB, or individually purified vfFadB. Reaction enzyme concentrations are shown in table format at the bottom of the figure. (Top) Initial rate of NAD(P)H consumption (μM min−1) fit to the initial, linear portion of absorbance assay data. (Middle) (circle) Total NAD(P)H consumed (mM) at one hour as quantified by absorbance assay. (diamond) The stoichiometrically equivalent NAD(P)H required to produce GC-MS quantified alcohols. Data points and error bars represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate reactions. (Bottom) Alcohol profiles quantified via GC-MS. Stacked bars represent molar fractions, calculated as the average molar concentrations across all present chain-lengths, corrected for propagated error of the total molar concentration. Reactions were carried out in triplicate (n=3), and absorbance assay for each reaction was carried out in technical triplicates (n=3). Values presented for absorbance assay (top and middle panels) represents the mean and standard deviation calculated from the mean value of each set of technical replicates, adjusted to account for background auto-oxidation of NAD(P)H.

To determine if β-ketoacyl-CoA reduction, or β-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydration is the slow step catalyzed by the bifunctional vfFadB subunit, we characterized the reaction rates of a purified vfFadBA complex with a point inactivation of thiolase activity (vfFadBA*) on commercially available C4 acetoacetyl-CoA and DL-hydroxybutyryl-CoA. Reaction rates on acetoacetyl-CoA were significantly lower than on DL-hydroxybutyryl-CoA at similar substrate concentrations (Figure S14), suggesting that the reduction of β-ketoacyl-CoAs to β-hydroxyacyl-CoAs is rate limiting in the reconstituted R-βox pathway.

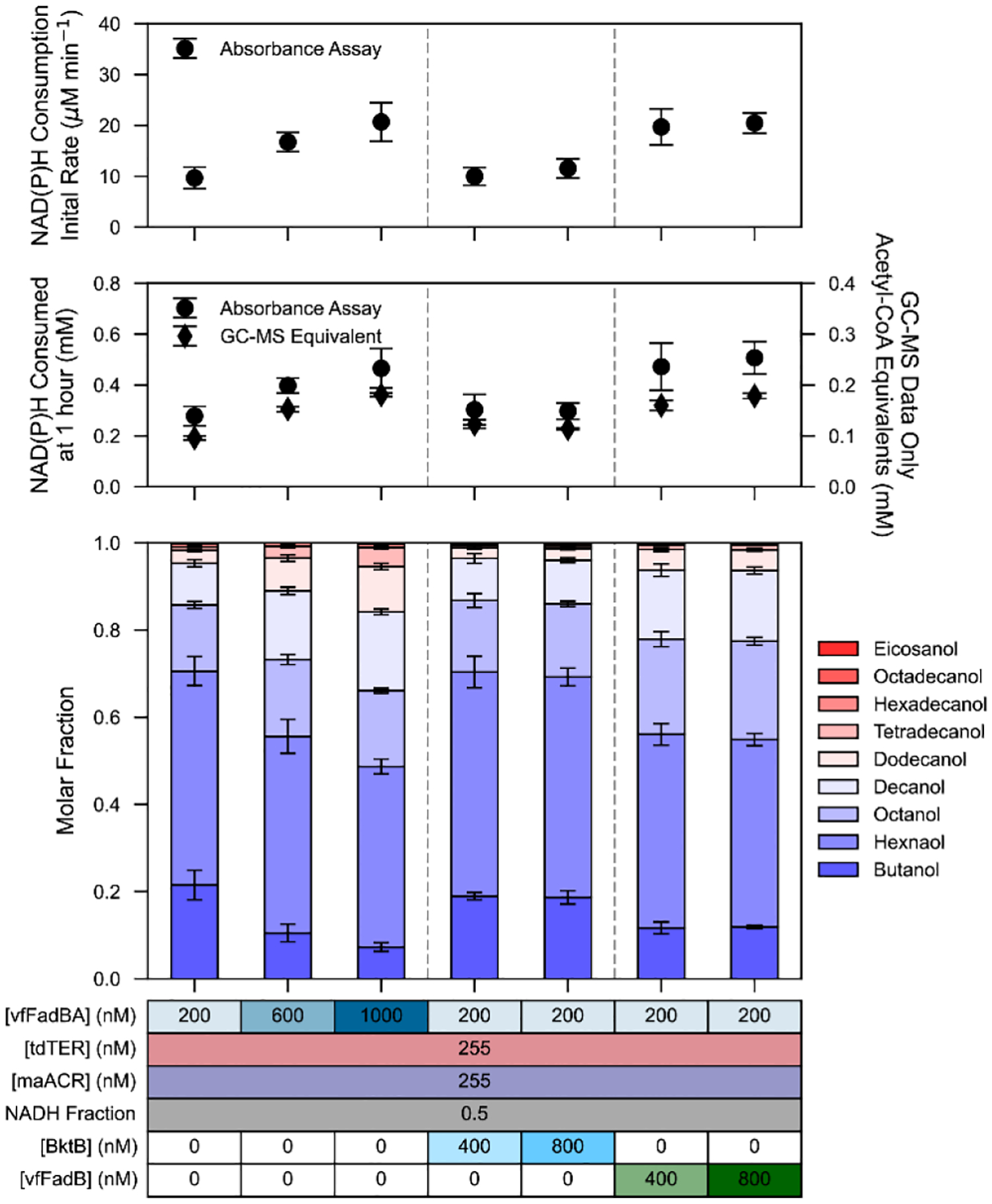

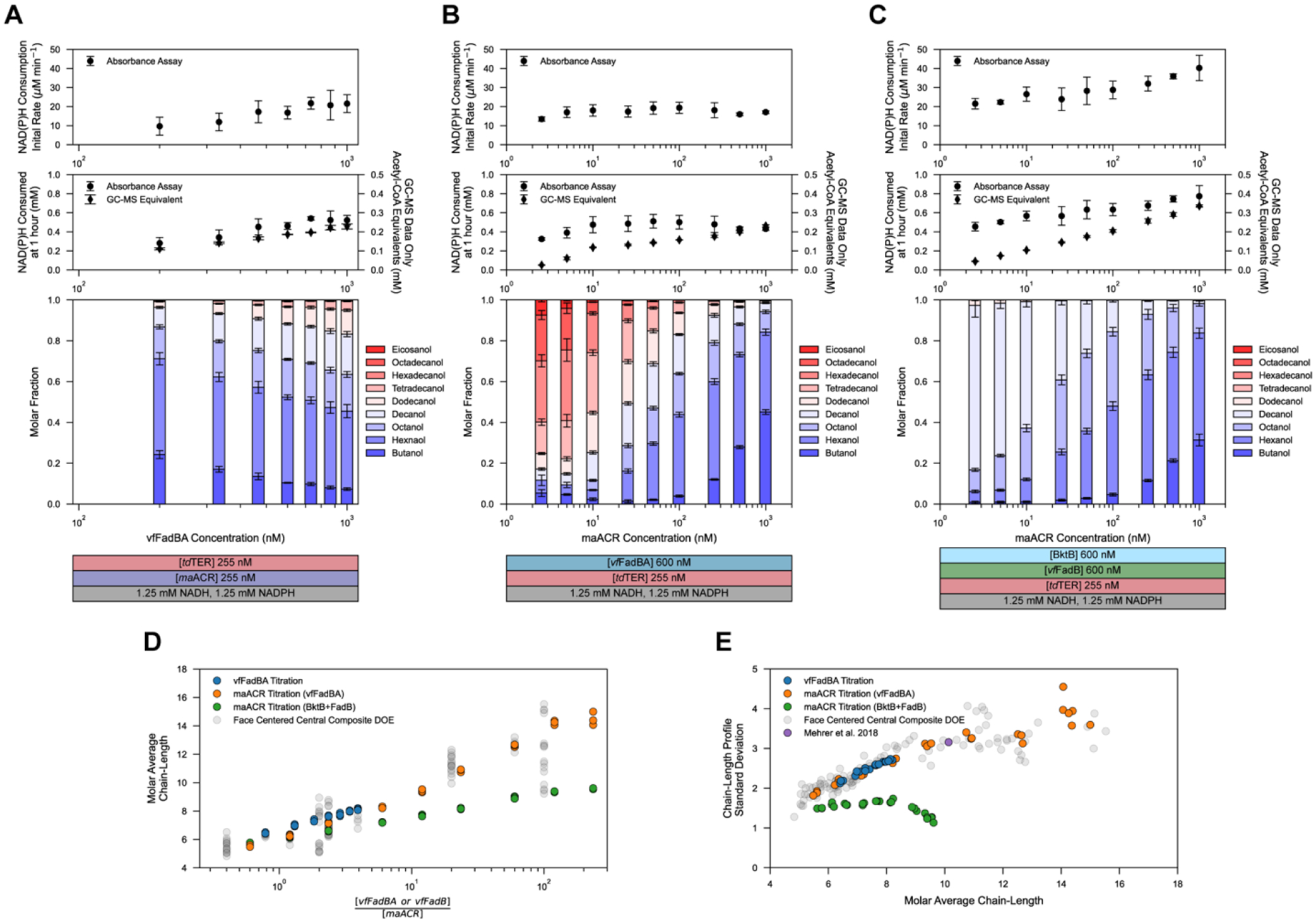

Titration of vfFadBA and maACR for Alcohol Product Profile Control

To further explore how the concentration ratio of vfFadBA and maACR can be used to control the average product chain-length, we carried out a series of experiments titrating the concentration of vfFadBA or maACR with other factors held at the midpoint value from the DOE study (Figure 4A and B). Trends observed in the data above were recapitulated in these experiments, with average chain length corresponding to a logarithmically increasing enzyme ratio, unconstrained by the depletion of NADH observed above (Figure 4D). Standard deviations of the product profile obtained in both titrations falls perfectly along previously observed trends, increasing with the average chain length (Figure 4E). Notably, the in vivo product profile reported by Mehrer et al. for alcohol production with vfFadBA, tdTER, and maACR R-βox strain coincides with the standard deviation and average chain length trend, suggesting that this phenomena may not be limited to the reconstituted in vitro pathway25.

Figure 4.

Titration of Elongation and Termination Enzyme Ratios.

(Top row) Titration of the concentration ratio of vfFadB and maACR changing the concentration of (A) vfFadBA, (B) maACR, and (C) maACR in a reaction system with BktB and vfFadB in place of the tri-functional vfFadBA. (Top subplots) Initial rate of NAD(P)H consumption (μM min−1). (Middle subplots) (circle) Total NAD(P)H consumed (mM) at one hour as quantified by the absorbance assay. (diamond) The stoichiometrically equivalent NAD(P)H required to produce GC-MS quantified alcohols. Data points and error bars represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate reactions. (Bottom subplots) Alcohol profiles quantified via GC-MS. Stacked bars represent molar fractions, calculated as the average molar concentrations across all present chain-lengths, corrected for propagated error of the total molar concentration. All reaction conditions were carried out in triplicate (n=3), with the absorbance assay for each reaction carried out in technical triplicate (n=3). Values presented for the absorbance assay (top and middle panels) represent the mean and standard deviation calculated from the mean value of each set of technical replicates adjusted to account for background auto-oxidation of NAD(P)H. (Bottom row) (D) Average chain-lengths as a function of enzyme ratio, and (E) standard deviation of the product profile as a function of the molar average chain-length. Each point represents an individual reaction from either titration experiments, or from the face-centered central composite experiment. The profile standard deviation and average chain-length calculated from the highest alcohol titer producing strains containing vfFadBA, tdTER, and maACR enzymes presented by Mehrer et al.25 is also shown.

We expected that product specificity might be achievable at high vfFadBA to maACR concentration ratios if a strict upper limit to chain-length elongation was implemented. Previous metabolic engineering strategies have taken advantage of the C4-C10 activity range of BktB to restrict carbon elongation21. We sought to determine if specificity for decanol could be achieved by pairing maACR and BktB. Titration of maACR in reactions with BktB, vfFadB, and tdTER resulted in specific (50–80%) decanol production at low maACR concentrations (Figure 4C); however, this came at the expense of significant reduction in the total conversion to alcohols. Molar average chain-lengths increased with increasing vfFadB to maACR ratios; however, the slope of this change was lower than that observed in reaction system with vfFadBA. Similar enzyme ratios required to reach C9-C10 average chain-lengths yielded ~C14 average chain lengths when vfFadBA was used (Figure 4D). Standard deviations of the product profile show increase specificity as the C10 upper limit is approached (Figure 4E).

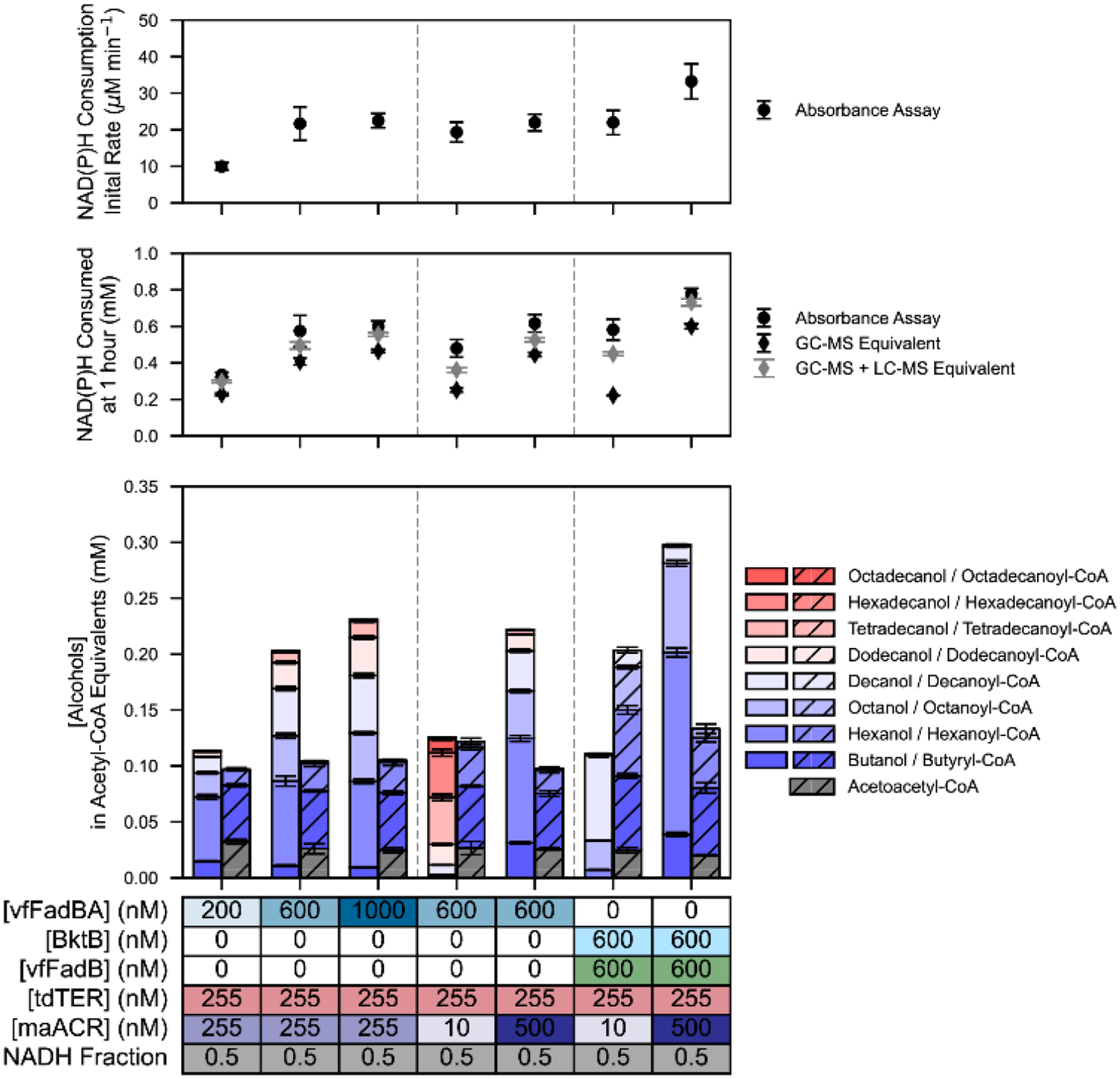

Quantification of Elongation Cycle Intermediates via LC-MS

To investigate how the chain-length and distribution of the intermediate metabolites change alongside alcohol product profiles, seven previously explored reaction conditions were selected for metabolite quantification via liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Conditions were selected that yielded significant differences in product profiles but still maintained at least 0.1 mM acetyl-CoA equivalents of alcohol production. Acyl-CoA and β-ketoacyl-CoA species were the predominant metabolite signals, and while signals for β-hydroxyacyl-CoA and trans-enoyl-CoA intermediates in the C4-C12 range were detected, they fell below the limit of accurate quantification (Figure S15). Concentrations of acetoacetyl-CoA and acyl-CoA species were determined based on a dilution series generated from commercially available standards. Results from the NAD(P)H absorbance assay, and intermediate metabolite and product alcohol profiles are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Quantification of Intermediate -CoA bound Metabolites.

(Top) Initial rate of NAD(P)H consumption (μM min−1) fit to initial linear portion of the absorbance assay data. (Middle) (circle) Total NAD(P)H consumed (mM) at one hour as quantified by absorbance assay. (black diamond) The stoichiometrically equivalent NAD(P)H required to produce GC-MS quantified alcohols. (gray diamond) The stoichiometrically equivalent NAD(P)H required to produce alcohols and quantified -CoA bound intermediates. Data points and error bars represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate reactions. (Bottom) Alcohol and -CoA bound intermediate metabolite profiles quantified by GC-MS and LC-MS respectively in terms of acetyl-CoA equivalents. Error bars represent the standard deviation of replicate reactions. All reactions were carried out in triplicate (n=3), and for each reaction technical triplicates (n=3) were measured via absorbance assay. Values presented for the absorbance assay (top and middle panels) represent the mean and standard deviation calculated from the mean value of each set of technical replicates, adjusted to account for background auto-oxidation of NAD(P)H.

Interestingly, we found that even when alcohols produced were predominantly C12 or longer, acyl-CoA profiles did not elongate beyond C10 decanoyl-CoA. This suggests that the profile of activity on different chain-lengths of maACR may be playing a significant role. Willis et al. found maACR was the most active on hexadecanoyl-CoA, with decreasing activity on longer or shorter chains33. We speculate that this affinity for longer chain-lengths paired with limiting enzyme concentrations results in the disproportionate conversion of low concentration long-chain species, even when butyryl-CoA and hexanoyl-CoA are present in similar concentrations as other reactions producing shorter alcohol profiles. A time course investigation of a single reaction condition, representative of the mid-point of the DOE factor space, showed that acetoacetyl-CoA, butanoyl-CoA, and hexanoyl-CoA concentrations were rapidly established, reaching an apparent steady-state by 5 minutes (Figure S16). Consistent with a constant concentration of the acyl-CoA profile, the profile of alcohol chain-lengths produced over the duration of the reaction (i.e., 60 mins) also remained relatively constant.

The concentration profile of -CoA bound intermediates reflects the thermodynamics of the cycle and the proposed bottleneck in β-ketoacyl-CoA reduction. Because the thiolase reaction is unfavorable in the condensation direction (ΔrG’° = 25.0 ± 0.7 kJ / mol), high reactant (acyl-CoA) concentrations, and low product (β-ketoacyl-CoA) concentrations are required for forward flux. Pairing this thermodynamic constraint with the extremely favorable trans-enoyl-CoA reduction (ΔrG’° = −50.6 ± 0.7 kJ/mol), leads to expectations of high acyl-CoA concentrations. Following similar arguments, one would expect that the favorability of the β-ketoacyl-CoA reductase reaction (ΔrG’° = −13.8 ± 1.4 kJ / mol) would drive metabolite concentrations to β-hydroxyacyl-CoA formation. Indeed, a reaction with vfFadBA and acetyl-CoA allowed to run to equilibrium supports the argument (Figure S17). However, we observed LC-MS signals for β-ketoacyl-CoA metabolites much higher than expected, further implying a kinetic bottleneck at this step consistent with the assays above. Finally, while not quantifiable, β-hydroxyacyl- and trans-enoyl-CoA concentrations are expected to be low relative to acyl-CoA, and in relatively equal abundances as β-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydratase reaction is a near equilibrium reaction (ΔrG’° = 3.3 ± 2.9 kJ / mol).

Discussion

The reversed β-oxidation pathway holds significant promise for the renewable bio-based production of oleochemicals. In comparison to the highly analogous fatty acid biosynthesis pathway, R-βox has higher theoretical yields, and is orthogonal to cellular growth; however, due to its partially synthetic nature and only recent attention, the development and understanding of factors controlling flux and product chain-length profiles is in a state of relative infancy, Through in vitro reconstitution of an alcohol producing R-βox pathway, we have explored how enzyme and co-factor concentrations influence pathway flux and product profiles in this non-decarboxylative cyclic carbon chain elongation pathway. The pathway enzymes, consisting of a tri-functional enzyme from β-oxidation, a trans-enoyl-CoA reductase, and an acyl-CoA reductase, were chosen based on previous published work for their activity on a broad range of chain-lengths, and represent a potential oleochemical production platform for products ranging from C4 to C16 in chain-length.

Through a combination of a DOE based exploration and individual enzyme assays, we were able to determine the rate limiting step of the cyclic elongation cycle as the reduction of ketoacyl- to hydroxyacyl-CoA catalyzed by the α-subunit (FadB) of the FadBA enzyme. This suggests a potential and unexpected enzyme engineering target in vfFadB and potentially other FadB enzymes, that could lead to improved R-βox flux in medium and long (≥C12) chain-length producing pathways. We also found that the average chain-length of product alcohols is a function of the ratio of concentration of the subunit catalyzing this rate limiting step, FadB, and ACR which catalyzes the terminal acyl-CoA reduction to alcohol. Utilizing the ratio of these two enzymes, the product profile in vitro could be adjusted from primarily short chain C4 and C6 products, up to long chain profiles of primarily C14 and longer alcohols. However, specificity could only be achieved for short chains in this original system. Experiments with BktB, a thiolase with activity capped at C10, revealed that specificity can also be achieved at an imposed upper limit with high ratios of FadB and ACR in vitro, albeit at the cost of total conversion of alcohols. Interestingly, when the alcohol product profile is primarily long chain-lengths, intermediate metabolite concentrations still consist primarily of C4 butyryl-CoA and C6 hexanoyl-CoA, suggesting that the activity of the terminating enzyme on different chain lengths plays an essential role in the transition between short and long chains.

It is interesting to compare our results to similar studies of the fatty acid biosynthesis (FAB) pathway (Figure S18). In their seminal study reconstituting E. coli’s FAB pathway, Yu et al., found that the enzymes FabI (an enoyl-ACP reductase) and FabZ (β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase) were rate limiting, with FabZ having the most significant effect36. The titration of the β-oxoacyl-ACP reductase, FabG, corresponding to the identified bottleneck reaction for our R-βox pathway, demonstrated no effect on pathway activity. In addition to the study from Yu et al, several in vivo FAB engineering efforts in E. coli have led to the development of a series of kinetic models37–39. In a more recent study guided by these kinetic models, Mains et al. demonstrated how FAB enzyme ratios could be used to control fatty acid chain-lengths in a system with a broadly active thioesterase31. Interestingly, in the FAB pathway, the ratio of β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (FabB or FabF) and thioesterase led to this control, compared to our R-βox pathway in which it was the ratio of dual functional FadB - presumably due to its rate control of elongation and terminating enzyme maACR. We note, that while it lies outside the scope of this manuscript, the set of data that we have collected and described here could be incorporated into the development of similar kinetic models for R-βox. These two otherwise highly similar pathways then, show significant differences in the kinetic factors controlling flux and chain-length distribution of products.

The enzymes comprising the reconstituted pathway presented here were selected for broad chain-length activity for a more continuous product profile response as well as a potential platform for the production of oleochemicals ranging from C4 – C16+. In particular, the choice of a tri-functional enzyme complex from β-oxidation in place of separate thiolase, hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (Hbd) and short chain enoyl-CoA hydratase (Crt) enzymes from Clostridium solventogenic or PHA biosynthetic pathways enables the synthesis of longer chain-length products. In R-βox studies to date, products from assembled pathways using enzymes from these other sources have been limited to a maximum C6 and C10 chain length respectively28, though it is unclear if this is due to the limit of these enzymes or if those pathways were limited by the paired thiolase. The choice to use an enzyme complex from β-oxidation, however, also comes with the consequence that the vfFadBA complex evolved in the context of oxidative flux instead of reductive. This evolutionary difference potentially has significant implications for the kinetics of various enzyme homolog options available for consideration in the assembly of a thiolase-dependent +2 carbon elongation cycle. It is plausible that a cycle comprised of enzymes from pathways that naturally operate in the reductive direction (e.g. the aforementioned Hbd and Crt enzymes from Clostridium acetobutylicum) would possess an entirely different kinetic bottleneck than the pathway that we have reconstituted in this study.

Our results also demonstrate how the ratio of elongation and termination pathway fluxes can be used to influence chain-length profiles; however, specificity was only achieved at low chain-length limits or with a chain-length limiting thiolase. Achieving highly specific product profiles necessary for the development of a bioprocess to produce oleochemicals then is likely to require the discovery and characterization, or engineering of enzymes with narrow specificity profiles that are active on acyl-CoAs or other -CoA intermediates of the pathway. Similar to the identification and engineering of chain-length specific acyl-ACP thioesterases for the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway40–48, the identification of chain-length specific acyl-CoA active enzymes or adaptation of acyl-ACP active enzymes for increased acyl-CoA activity is a likely route to achieve specificity. Few examples of -CoA active, chain length specific thioesterases exist in the present literature. Only recently Wang et al, described a C8/C10 specific acyl-CoA and β-hydroxyacyl-CoA active thioesterase enzyme from Anaerococcus tetradium23. Unlike fatty acid biosynthesis where the production of fatty acids cannot be fully capped without sacrificing essential membrane precursors, the orthogonality of R-βox allows for the potential to identify or engineer thiolases with upper limits of chain-length activity for each chain-length, like the C4 limited AtoB20,49 or C10 limited BktB. Recently, Vögeli et al. used a high throughput cell free screening of R-βox pathway enzymes to identify a thiolase with strong activity and C6 upper limit from Clostridium kluyveri30. To our knowledge, thiolases with activity limits at other chain-lengths are yet to be fully characterized or discovered.

In conclusion, we have reconstituted in vitro an alcohol producing reversed β-oxidation pathway and interrogated factors controlling flux and product carbon chain-length distribution. Using this system, we identified the kinetic bottleneck and enzyme ratios leading to control of the average product chain-length. We also investigated how a chain-length limiting thiolase can be used to achieve specificity. Our results emphasize the necessity of careful consideration of enzyme ratios in future studies and highlight potential enzyme engineering targets for increasing flux in the carbon-chain elongating reversed β-oxidation pathway.

Materials and Methods

Enzyme Expression and Purification

Selected enzymes were expressed from pET28 vectors (see Supplemental File). Point inactivation of the thiolase subunit of vfFadBA* was made by C91A mutation. To prevent possible complexing of the native E. coli FadA with His-tagged vfFadB, the vfFadBA, vfFadBA*, and vfFadB enzymes were expressed and purified from a ΔfadBA BL21(DE3) E. coli strain constructed via a combination of λ-Red homologous recombination and CRISPR counter selection as previously described25. Cultures harboring the respective plasmid for each protein were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of approximately 0.6 before decreasing the temperature to 16°C and inducing with 100 μM IPTG. After overnight growth at 16°C, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000 rpm (11444 g) at 4°C for 15 minutes and re-suspended in the corresponding lysis buffer. 1 mM 1,4-Dithiothreitol, Halt™ protease inhibitor (Thermo Scientific), and Benzonase® nuclease (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the re-suspension, followed by sonication (Fisher 550 Sonic Dismembrator, amplitude = 30%, time = 10 min with 1 sec on/ 1 sec off). Supernatant of the lysate was collected by centrifugation at 12000 rpm (25482 g) at 4°C for 30 minutes, and then filtered through a 0.45 μm filter to collect the soluble fraction. All enzymes were purified with the aid of an ÄKTA Start system and automatic fraction collector. Buffers used in the purification of each enzyme were selected based on previously published purifications of the enzyme32,33,35 or close homologs and are detailed in Table S1. To increase the purity of the MBP-tagged maACR a two-column protocol was used where the total soluble protein was first bound to a 5 mL MBPTrap HP column (Cytiva), and further purified from the eluted fractions with a 5 mL His-Trap column. All other enzymes were purified by Ni-NTA affinity with His-Trap columns alone. A linear gradient of the elution buffer from 0 to 100% was used for the elution of each enzyme. Selected eluted fractions were buffer exchanged via PD-10 desalting columns (Cytiva) into their respective storage buffer, pooled, aliquoted, flash frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for future use. SDS-PAGE was used to confirm the identity and relative purity of each enzyme (Figure S1). The concentration of each enzyme was determined via absorbance at 280 nm using estimated extinction coefficients from the ProtParam tool by ExPASy.

in vitro Pathway Reactions

Reactions with the reconstituted R-βox pathway were carried out in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 0.3 mg/mL Bovine-Serum-Albumin, 1 mM DTT, adjusted to pH = 7.2 with NaOH. Reactions were prepared via the ordered addition of NADH, NADPH, vfFadBA, tdTER, maACR to the buffer, pre-incubated at 30°C for 10 minutes, and then initiated with the addition of 1 mM acetyl-CoA and rapidly mixed by pipetting. In experiments with vfFadB or BktB, these enzymes were added in place of, or directly following vfFadBA. All reactions were carried out at 30°C at a total initial reaction volume of 1 mL unless otherwise noted. To minimize batch effects, reactions within an experiment were run in a random order.

Absorbance Assay

At reaction onset, three technical replicate aliquots of 100 μL were transferred to a UV clear 96-well plate to monitor NADH and NADPH absorbance at 340 nM (ε = 6.22 mM-1 cm-1) in a Tecan Infinite M1000 plate reader. Pathlength corrections for the absorbance data were made by measuring the absorbance at 900 and 977 nm and applying a k-factor (0.136) measured for the reaction buffer with a Genesys 20 Spectrophotometer. Initial rates of NAD(P)H consumption were calculated via a linear fit to the first five minutes of reaction data. Both initial rates, and the amount of NAD(P)H consumed at one hour was corrected for non-enzymatic NAD(P)H oxidation with data from a representative no-enzyme control run in parallel containing the same NADH and NADPH concentrations.

GC-MS Quantification of Product Alcohols

At one hour, 400 μL of each reaction was extracted with 200 μL ethyl-acetate for GC-MS analysis. Quantification of the extracted alcohols was carried out on a Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010S using split-less injection in Fast Automated Scan/SIM mode scanning between 30 and 250 m/z. Alcohol concentrations in the ethyl-acetate extractions were quantified using a representative ion fit against a prepared external standard curve. Concentrations in the original reaction were estimated using extraction efficiencies determined from standards doped into the reaction buffer and extracted as above.

Product profiles of each reaction were quantified in terms of total molar concentration of alcohols (), concentrations normalized to either stoichiometric NAD(P)H equivalents (), or stoichiometric acetyl-CoA equivalents (), mole fractions of each observed alcohol (), average molar chain-length (), and standard deviation of the product chain-length profile (), where is the carbon chain-length (i.e., = 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 or 20), is the molar concentration of each quantified alcohol, and is the average chain-length.

Enzyme Assay for Determination of vfFadBA Rate Limiting Step

in vitro reactions to determine the rate limiting step of the vfFadBA complex were carried out with commercially available C4 substrates acetoacetyl-CoA (Cayman Chemical Company) and DL-β-hydroxybutyryl-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich). Reaction progress was monitored as the decreasing absorbance of NADH at 340 nm in a Nanodrop 2000C spectrophotometer. All reactions were conducted at room temperature (~25°C), with a total volume of 200 μL in UV-clear cuvettes. The reaction buffer for reactions with DL-β-hydroxybutyryl-CoA as substrate was the same as above for reactions with the full pathway. For reactions with acetoacetyl-CoA as substrate Bovine Serum Albumin was omitted due to solubility issues with the substrate. vfFadBA* concentration was 100 nM and 20 nM for the acetoacetyl-CoA and DL-β-hydroxybutyryl-CoA reactions respectively. For coupled reactions, tdTER was included in excess at 1000 nM. The enzyme(s) and NADH were added to the reaction buffer and allowed to equilibrate for at least 90 seconds before addition of the substrate to initialize the reaction. Initial rates for each reaction were determined from the linear portion of the absorbance curve.

LC-MS Quantification of -CoA Intermediate Metabolites

For experiments quantifying the concentration of -CoA bound intermediate metabolites, a 100 μL aliquot of the reaction was quenched with 400 μL of an ice-cold equivolume mixture of acetonitrile and methanol. For the timecourse experiment, samples were harvested sequentially from a 2.5 mL reaction volume at 1, 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes. Samples were spun down at 16,000 g for 10 minutes. Samples supernatants were dried under a sterile N2 sparge, and re-suspended to one-third of the initial volume in Solvent A (97:3 H2O:methanol with 10 mM tributylamine adjusted to pH 8.2 using 10 mM acetic acid). The LC-MS method was conducted using a Vanquish ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system (Thermo Scientific) coupled to a hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer (Q Exactive™; Thermo Scientific) equipped with electrospray ionization operating in negative-ion mode. The chromatography was performed at 25°C using a 2.1 × 100 mm reverse-phase C18 column with a 1.7 μm particle size (Water™; Acquity UHPLC BEH). The chromatography gradient used Solvent A and Solvent B (100% methanol) as follows: : 0–2.5 min, 5% B; 2.5–5 mins, 20% B; 5–7.5 mins, 20% B; 7.5–13 mins, 55% B; 13–15.5 mins, 95% B; 15.5–18.5, 95% B; 18.5–19 mins, 5% B; 19–25 mins, 5% B. The flow rate was held constant at 0.2 mL/min. Eluent from the LC column was directed to waste up to 2 minutes, injected into the MS for analysis from 2–19 minutes, and redirected towards waste for the remainder of each run. The MS parameters included the following: Full MS-SIM (single ion monitoring) scanning between 100 and 1200 m/z, automatic control gain, target 1e6, maximum injection time 40 ms, and a resolution of 70000 full width at half maximum; parallel reaction monitoring with an isolation window of 1.4 m/z, and a (N)CE of 30.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to Jonathan Greenhalgh and Phil Romero for the gift of the plasmid used in the purification of MBP-tagged maACR. The authors also wish to thank Michael Jindra for helpful discussions. This work was funded by The US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture under award number 2020-67021-31140. D.C. was additionally supported by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Award Number DE-SC0018409 and is a recipient of the NIH Biotechnology Training Program Fellowship (NIGMS 5 T32 GM08349).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The following files are available free of charge.

Supplemental figures and tables (PDF)

Plasmid files used in this study (ZIP)

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- (1).Marcheschi RJ; Li H; Zhang K; Noey EL; Kim S; Chaubey A; Houk KN; Liao JC A Synthetic Recursive “+1” Pathway for Carbon Chain Elongation. ACS Chem. Biol 2012, 7 (4), 689–697. 10.1021/cb200313e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Yan Q; Pfleger BF Revisiting Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Microbial Synthesis of Oleochemicals. Metab. Eng 2020, 58, 35–46. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nivina A; Yuet KP; Hsu J; Khosla C Evolution and Diversity of Assembly-Line Polyketide Synthases. Chem. Rev 2019, 119 (24), 12524–12547. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Daletos G; Katsimpouras C; Stephanopoulos G Novel Strategies and Platforms for Industrial Isoprenoid Engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38 (7), 811–822. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Avalos M; Garbeva P; Vader L; Van Wezel GP; Dickschat JS; Ulanova D Biosynthesis, Evolution and Ecology of Microbial Terpenoids. Nat. Prod. Rep 2022, 39 (2), 249–272. 10.1039/d1np00047k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Heath RJ; Rock CO The Claisen Condensation in Biology. Nat. Prod. Rep 2002, 19 (5), 581–596. 10.1039/b110221b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Liu L; Zhou S; Deng Y The 3-Ketoacyl-CoA Thiolase: An Engineered Enzyme for Carbon Chain Elongation of Chemical Compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2020, 104 (19), 8117–8129. 10.1007/s00253-020-10848-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zhou S; Hao T; Xu S; Deng Y Coenzyme A Thioester-Mediated Carbon Chain Elongation as a Paintbrush to Draw Colorful Chemical Compounds. Biotechnol. Adv 2020, 43 (June), 107575. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Richter H; Molitor B; Diender M; Sousa DZ; Angenent LT A Narrow PH Range Supports Butanol, Hexanol, and Octanol Production from Syngas in a Continuous Co-Culture of Clostridium Ljungdahlii and Clostridium Kluyveri with in-Line Product Extraction. Front. Microbiol 2016, 7 (NOV), 01773. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).San-Valero P; Fernández-Naveira; Veiga MC; Kennes C Influence of Electron Acceptors on Hexanoic Acid Production by Clostridium Kluyveri. J. Environ. Manage 2019, 242 (February), 515–521. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fiedler S; Steinbüchel A; Rehm BHA PhaG-Mediated Synthesis of Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoates) Consisting of Medium-Chain-Length Constituents from Nonrelated Carbon Sources in Recombinant Pseudomonas Fragi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2000, 66 (5), 2117–2124. 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2117-2124.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Huijberts GNM; De Rijk TC; De Waard P; Eggink G 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of Pseudomonas Putida Fatty Acid Metabolic Routes Involved in Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoate) Synthesis. J. Bacteriol 1994, 176 (6), 1661–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Rehm BHA; Krüger N; Steinbüchel A A New Metabolic Link between Fatty Acid de Novo Synthesis and Polyhydroxyalkanoic Acid Synthesis. The PhaG Gene from Pseudomonas Putida KT2440 Encodes a 3-Hydroxyacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein-Coenzyme a Transferase. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273 (37), 24044–24051. 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Tseng HC; Martin CH; Nielsen DR; Prather KLJ Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia Coli for Enhanced Production of (R)- And (S)-3-Hydroxybutyrate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2009, 75 (10), 3137–3145. 10.1128/AEM.02667-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).R. SC; I. LE; Yasumasa D; Antonino B; Myung CK; C. LJ Driving Forces Enable High-Titer Anaerobic 1-Butanol Synthesis in Escherichia Coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2011, 77 (9), 2905–2915. 10.1128/AEM.03034-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Dekishima Y; Lan EI; Shen CR; Cho KM; Liao JC Extending Carbon Chain Length of 1-Butanol Pathway for 1-Hexanol Synthesis from Glucose by Engineered Escherichia Coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (30), 11399–11401. 10.1021/ja203814d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Machado HB; Dekishima Y; Luo H; Lan EI; Liao JC A Selection Platform for Carbon Chain Elongation Using the CoA-Dependent Pathway to Produce Linear Higher Alcohols. Metab. Eng 2012, 14 (5), 504–511. 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Dellomonaco C; Clomburg JM; Miller EN; Gonzalez R Engineered Reversal of the β-Oxidation Cycle for the Synthesis of Fuels and Chemicals. Nature 2011, 476 (7360), 355–359. 10.1038/nature10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Clomburg JM; Vick JE; Blankschien MD; Rodríguez-Moyá M; Gonzalez R A Synthetic Biology Approach to Engineer a Functional Reversal of the β-Oxidation Cycle. ACS Synth. Biol 2012, 1 (11), 541–554. 10.1021/sb3000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kim S; Clomburg JM; Gonzalez R Synthesis of Medium-Chain Length (C6–C10) Fuels and Chemicals via β-Oxidation Reversal in Escherichia Coli. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2015, 42 (3), 465–475. 10.1007/s10295-015-1589-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kim S; Gonzalez R Selective Production of Decanoic Acid from Iterative Reversal of β-Oxidation Pathway. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2018, 115 (5), 1311–1320. 10.1002/bit.26540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wu J; Wang Z; Duan X; Zhou P; Liu P; Pang Z; Wang Y; Wang X; Li W; Dong M Construction of Artificial Micro-Aerobic Metabolism for Energy- and Carbon-Efficient Synthesis of Medium Chain Fatty Acids in Escherichia Coli. Metab. Eng 2019, 53 (October 2018), 1–13. 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang ZQ; Song H; Koleski EJ; Hara N; Park DS; Kumar G; Min Y; Dauenhauer PJ; Chang MCY A Dual Cellular–Heterogeneous Catalyst Strategy for the Production of Olefins from Glucose. Nat. Chem 2021, 13 (12), 1178–1185. 10.1038/s41557-021-00820-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tseng HC; Prather KLJ Controlled Biosynthesis of Odd-Chain Fuels and Chemicals via Engineered Modular Metabolic Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109 (44), 17925–17930. 10.1073/pnas.1209002109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Mehrer CR; Incha MR; Politz MC; Pfleger BF Anaerobic Production of Medium-Chain Fatty Alcohols via a β-Reduction Pathway. Metab. Eng 2018, 48 (May), 63–71. 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).McMahon MD; Prather KLJ Functional Screening and in Vitro Analysis Reveal Thioesterases with Enhanced Substrate Specificity Profiles That Improve Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production in Escherichia Coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2014, 80 (3), 1042–1050. 10.1128/AEM.03303-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cintolesi A; Clomburg JM; Gonzalez R In Silico Assessment of the Metabolic Capabilities of an Engineered Functional Reversal of the β-Oxidation Cycle for the Synthesis of Longer-Chain Products. Metab. Eng 2014, 23, 100–115. 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Tarasava K; Lee SH; Chen J; Köpke M; Jewett MC; Gonzalez R Reverse β-Oxidation Pathways for Efficient Chemical Production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2022, 49 (2), kuac003. 10.1093/jimb/kuac003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Cheong S; Clomburg JM; Gonzalez R Energy-and Carbon-Efficient Synthesis of Functionalized Small Molecules in Bacteria Using Non-Decarboxylative Claisen Condensation Reactions. Nat. Biotechnol 2016, 34 (5), 556–561. 10.1038/nbt.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Vögeli B; Schulz L; Garg S; Tarasava K; Clomburg JM; Lee SH; Gonnot A; Moully EH; Kimmel BR; Tran L; Zeleznik H; Brown SD; Simpson SD; Mrksich M; Karim AS; Gonzalez R; Köpke M; Jewett MC Cell-Free Prototyping Enables Implementation of Optimized Reverse β-Oxidation Pathways in Heterotrophic and Autotrophic Bacteria. Nat. Commun 2022, 13 (1), 3058. 10.1038/s41467-022-30571-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Mains K; Peoples J; Fox JM Kinetically Guided, Ratiometric Tuning of Fatty Acid Biosynthesis. Metab. Eng 2022, 69, 209–220. 10.1016/j.ymben.2021.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Sah-Teli SK; Hynönen MJ; Sulu R; Dalwani S; Schmitz W; Wierenga RK; Venkatesan R Insights into the Stability and Substrate Specificity of the E. Coli Aerobic β-Oxidation Trifunctional Enzyme Complex. J. Struct. Biol 2020, 210 (3), 107494. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Willis RM; Wahlen BD; Seefeldt LC; Barney BM Characterization of a Fatty Acyl-CoA Reductase from Marinobacter Aquaeolei VT8: A Bacterial Enzyme Catalyzing the Reduction of Fatty Acyl-CoA to Fatty Alcohol. Biochemistry 2011, 50 (48), 10550–10558. 10.1021/bi2008646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Geertz-Hansen HM; Blom N; Feist AM; Brunak S; Petersen TN Cofactory: Sequence-Based Prediction of Cofactor Specificity of Rossmann Folds. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma 2014, 82 (9), 1819–1828. 10.1002/prot.24536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bond-Watts BB; Weeks AM; Chang MCY Biochemical and Structural Characterization of the Trans-Enoyl-Coa Reductase from Treponema Denticola. Biochemistry 2012, 51 (34), 6827–6837. 10.1021/bi300879n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yu X; Liu T; Zhu F; Khosla C In Vitro Reconstitution and Steady-State Analysis of the Fatty Acid Synthase from Escherichia Coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2011, 108 (46), 18643–18648. 10.1073/pnas.1110852108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Ruppe A; Fox JM Analysis of Interdependent Kinetic Controls of Fatty Acid Synthases. ACS Catal. 2018, 8 (12), 11722–11734. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ruppe A; Mains K; Fox JM A Kinetic Rationale for Functional Redundancy in Fatty Acid Biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117 (38), 23557–23564. 10.1073/pnas.2013924117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Peoples J; Ruppe S; Mains K; Cipriano EC; Fox JM A Kinetic Framework for Modeling Oleochemical Biosynthesis in Escherichia Coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2022, No. June, 3149–3161. 10.1002/bit.28209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Yuan L; Voelker TA; Hawkins DJ Modification of the Substrate Specificity of an Acyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Thioesterase by Protein Engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1995, 92 (23), 10639–10643. 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Torella JP; Ford TJ; Kim SN; Chen AM; Way JC; Silver PA Tailored Fatty Acid Synthesis via Dynamic Control of Fatty Acid Elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110 (28), 11290–11295. 10.1073/pnas.1307129110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Choi YJ; Lee SY Microbial Production of Short-Chain Alkanes. Nature 2013, 502 (7472), 571–574. 10.1038/nature12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Grisewood MJ; Hernández-Lozada NJ; Thoden JB; Gifford NP; Mendez-Perez D; Schoenberger HA; Allan MF; Floy ME; Lai RY; Holden HM; Pfleger BF; Maranas CD Computational Redesign of Acyl-ACP Thioesterase with Improved Selectivity toward Medium-Chain-Length Fatty Acids. ACS Catal. 2017, 7 (6), 3837–3849. 10.1021/acscatal.7b00408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Hernández Lozada NJ; Lai R-Y; Simmons TR; Thomas KA; Chowdhury R; Maranas CD; Pfleger BF Highly Active C(8)-Acyl-ACP Thioesterase Variant Isolated by a Synthetic Selection Strategy. ACS Synth. Biol 2018, 7 (9), 2205–2215. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Jing F; Zhao L; Yandeau-Nelson MD; Nikolau BJ Two Distinct Domains Contribute to the Substrate Acyl Chain Length Selectivity of Plant Acyl-ACP Thioesterase. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 860. 10.1038/s41467-018-03310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Sarria S; Bartholow TG; Verga A; Burkart MD; Peralta-Yahya P Matching Protein Interfaces for Improved Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Production. ACS Synth. Biol 2018, 7 (5), 1179–1187. 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Ziesack M; Rollins N; Shah A; Dusel B; Webster G; Silver PA; Way JC Chimeric Fatty Acyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Thioesterases Provide Mechanistic Insight into Enzyme Specificity and Expression. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2018, 84 (10), 02868–17. 10.1128/AEM.02868-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Banerjee D; Jindra MA; Linot AJ; Pfleger BF; Maranas CD EnZymClass: Substrate Specificity Prediction Tool of Plant Acyl-ACP Thioesterases Based on Ensemble Learning. Curr. Res. Biotechnol 2022, 4 (September 2021), 1–9. 10.1016/j.crbiot.2021.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Feigenbaum J; Schulz H Thiolases of Escherichia Coli: Purification and Chain Length Specificities. J. Bacteriol 1975, 122 (2), 407–411. 10.1128/jb.122.2.407-411.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.