Abstract

The actinomycin synthetases ACMS I, II, and III catalyze the assembly of the acyl peptide lactone precursor of actinomycin by a nonribosomal mechanism. We have cloned the genes of ACMS I (acmA) and ACMS II (acmB) by hybridization screening of a cosmid library of Streptomyces chrysomallus DNA with synthetic oligonucleotides derived from peptide sequences of the two enzymes. Their genes were found to be closely linked and are arranged in opposite orientations. Hybridization mapping and partial sequence analyses indicate that the gene of an additional peptide synthetase, most likely the gene of ACMS III (acmC), is located immediately downstream of acmB in the same orientation. The protein sequence of ACMS II, deduced from acmB, shows that the enzyme contains two amino acid activation domains, which are characteristic of peptide synthetases, and an additional epimerization domain. Heterologous expression of acmB from the mel promoter of plasmid PIJ702 in Streptomyces lividans yielded a functional 280-kDa peptide synthetase which activates threonine and valine as enzyme-bound thioesters. It also catalyzes the dipeptide formation of threonyl–l-valine, which is epimerized to threonyl–d-valine. Both of these dipeptides are enzyme bound as thioesters. This catalytic activity is identical to the in vitro activity of ACMS II from S. chrysomallus.

The actinomycins are a class of chromopeptide lactones produced by various Streptomyces strains. They contain two pentapeptide lactone rings attached to chromophoric 4,6-dimethylphenoxazinone-1,9-dicarboxylic acid (actinocin) in an amide-like fashion. Actinocin is formally derived from the compound 4-methyl-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (4-MHA), but actually the bicyclic actinomycins arise from the oxidative condensation of two preformed monocyclic 4-MHA pentapeptide lactones (12). Previous investigations have revealed that the formation of the 4-MHA pentapeptide lactones is catalyzed by three actinomycin synthetases (ACMS I, II, and III) (13, 15). ACMS I (45 kDa) is a 4-MHA–AMP ligase which activates 4-MHA as adenylate. The five amino acids of the pentapeptide lactone ring of actinomycin (NH2-cyclo[Thr–d-Val–Pro–N-methyl-Gly–N-methyl-Val] for actinomycin D) are assembled by ACMS II (280 kDa) and ACMS III (480 kDa) which from their properties belong to the class of peptide synthetases (13, 26, 27). ACMS II catalyzes the activation of threonine and valine. In the presence of ACMS I, which supplies 4-MHA–adenylate, 4-MHA–threonine and 4-MHA–threonyl–d-valine (via 4-MHA–threonyl–l-valine) are formed on the surface of ACMS II. In the absence of 4-MHA or ACMS I, purified ACMS II can synthesize both threonyl–l-valine and threonyl–d-valine, though to a lesser extent than the corresponding 4-MHA dipeptides can. The epimerization of valine is catalyzed by ACMS II at the acyl-dipeptide stage. An analysis of ACMS III suggests that it elongates the 4-MHA–Thr–d-Val dipeptide by successive incorporation of proline, N-methylglycine (sarcosine), and N-methyl-l-valine into the growing peptide chain (13). N-methylation is an additional feature of ACMS III. A total cell-free system for 4-MHA pentapeptide lactone synthesis is not available yet. Thus, it is not known how 4-MHA dipeptide transfer from ACMS II to ACMS III is accomplished, nor is the mechanism of lactone formation and release from the 4-MHA pentapeptide known.

The available data indicate that ACMS II and ACMS III contain two- and three-amino-acid activation domains, respectively. It is known that activation domains of peptide synthetases are highly conserved in their sequences and are composed of a segment for amino acid adenylation and a segment for binding the activated amino acid as a thioester (17, 24, 25, 32). Thioester formation occurs via the thiol group of 4′-phosphopantetheine, which is a covalently bound cofactor of the activation domain. ACMS II and III both contain 4′-phosphopantetheine. In contrast, ACMS I has no 4′-phosphopantetheine cofactor, consistent with the finding that it does not form a thioester with 4-MHA. Data from previous work pointed instead to the formation of a 4-MHA thioester with ACMS II (26). In order to investigate the modular structure of the ACMSs and the reaction mechanisms in more detail, we set out to clone the ACMS genes from Streptomyces chrysomallus with oligonucleotide probes derived from partial sequences of ACMS I and II. We show that the genes of ACMS I and II and of a third peptide synthetase, most probably the gene of ACMS III (acmA, acmB, and acmC, respectively) are closely linked, forming a gene cluster. A total sequence determination of acmB and the characterization of the heterologously expressed functional active gene product confirm the significance of this peptide synthetase gene cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth of organisms.

Streptomyces lividans 1326 (John Innes Collection) was maintained at 30°C on R5 plates (10). Submerged growth took place for 2 to 3 days in 100 ml of YEME liquid medium (10) in 300-ml flasks equipped with steel springs and shaken at 200 rpm. The transformation of S. lividans was performed as described by Hopwood et al. (10). For heterologous expression of acmB in S. lividans, transformants harboring plasmid pACM5 were grown for 2 days in 100 ml of YEME–5 μg of thiostrepton per ml; 5 ml of glucose (20% [wt/vol]) was added, and growth was continued for 1 day. Escherichia coli strains were DH5α and DH1 (7).

Protein purification from S. lividans.

Ten grams of mycelium (wet weight; harvested by suction filtration) was suspended in 100 ml of ice-cold buffer AS (10% glycerol [wt/vol], 200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 30 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 1,4 dithiothreitol, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). After passage of the suspension through a French press at 10,000 lb/in2, 1 mg of DNase I (Sigma; 90% protein = 440 Kunitz U) was added and the homogenate was stirred for 40 min on ice. Buffer AZ (95% glycerol [wt/vol], 850 mM NaCl) was added to give a final concentration of 300 mM NaCl, and after centrifugation (20 min, 15,000 × g, 4°C) 0.03 volume of neutralized polymin P (BASF; 10% [wt/vol]) was added to the supernatant. After standing on ice for 30 min, the precipitate was removed by centrifugation (25 min, 15,000 × g, 4°C). Ammonium sulfate (saturated solution at 4°C) was added to give 60% saturation, and after incubation for 5 h on ice the protein precipitate was collected by centrifugation (30 min, 15,000 × g, 4°C). Proteins were resuspended in buffer B (15% glycerol [wt/vol], 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 4 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF). Protein portions of 100 mg were purified by gel filtration on an Ultrogel-AcA-34 column at 4°C (Biosepra; range, 20 to 350 kDa; 2 by 48 cm) with buffer B and a fraction volume of 4.2 ml. For fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) purification, Ultrogel-AcA-34 fractions showing thioester formation activity with [14C]Val and [14C]Thr (e.g., fractions 14 to 19 in Fig. 4) were applied to a Resource-Q column (Pharmacia; polystyrene-divinyl benzene-based anion exchanger) at room temperature. Proteins were eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 400 mM in 70 min; flow rate, 1 ml/min) in buffer B. ACMS II isolated from S. lividans transformants was found to elute with 220 mM NaCl as did ACMS II isolated from S. chrysomallus (data not shown).

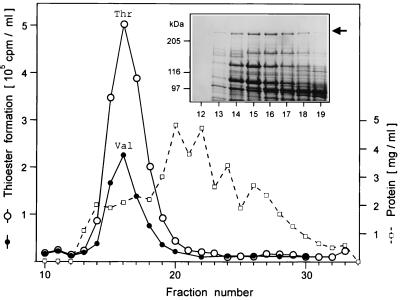

FIG. 4.

Gel filtration of the engineered ACMS II on Ultrogel-AcA-34. Detection of thioester formation with [14C]threonine (open circles) or [14C]valine (solid circles) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The inset shows the results of an SDS-PAGE analysis (5% polyacrylamide; Coomassie blue-stained) of fractions (15-μl aliquots) in which enzymatic activity was detected. The protein concentration is shown by the dashed curve. The arrow indictaes ACMS II.

Thioester formation assay and unit definition.

A 100-μl protein fraction was mixed with 3 μl of 14C-labelled amino acid (100 μCi/ml)–2 μl of MgCl2 (1 M)–15 μl of ATP (100 mM). After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, the reaction was stopped with 2 ml of 7% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and protein was precipitated for 30 min on ice. The precipitate was collected on ME25 filters (Schleicher & Schuell), washed with 20 ml of TCA (7%), and dried, and protein-bound label was identified by liquid scintillation counting in a Wallac 1409 counter. One unit of ACMS II is the amount of enzyme which covalently binds 1 nmol of threonine in 30 min at 30°C.

SDS-PAGE analysis of ACMS II with covalently bound reaction intermediates.

Engineered ACMS II (after Ultrogel-AcA-34 gel filtration; 0.04 U per reaction) was incubated for thioester formation with [14C]threonine or [14C]valine. Protein was precipitated with TCA and collected by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The precipitate was washed twice with 2 ml TCA (7%) and resuspended in a 50-μl solution of 15% (wt/vol) glycerol, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Control samples lacking ATP were prepared in parallel. Two microliters of 40% sucrose–0.25% bromphenol blue was added, and proteins were separated by SDS–4% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The Coomassie blue-stained gel was vacuum dried on a filter sheet (Whatman 3MM). Proteins with covalently bound label were identified by autoradiography (film NIF100; Konica).

Isolation of reaction intermediates from ACMS II and chromatographic analysis.

Recombinant ACMS II purified from S. lividans (0.14 U after FPLC purification) was incubated for thioester formation with 14C-labelled valine in the presence of 3 mM unlabelled threonine. Protein was precipitated with TCA and collected by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The precipitate was washed twice with 2 ml TCA (7%) and twice with 2 ml EtOH, dried at 37°C, and resuspended in 60 μl of formic acid. A 30-μl portion of the resuspended protein was mixed with 0.4 ml of performic acid (cleavage of thioester bonds); the remaining 30-μl portion was mixed with 0.4 ml of formic acid (control). After incubation for 20 h at 26°C, the samples were dried in a vacuum centrifuge, resuspended in 60 μl of formic acid, and analyzed on silica 60 thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Merck) with the solvent system n-butanol–acetic acid–H2O (4:1:1 [vol/vol/vol]). Labelled compounds were detected by autoradiography (Rf for [14C]Val = 0.40). In the control reactions (no cleavage of thioester bonds) the label remained protein bound at the start position (data not shown). In the cleavage reaction, two labelled compounds with Rf values of 0.45 and 0.50 (expected to be Thr–d-[14C]Val and Thr–l-[14C]Val, respectively) were scraped from silica plates, extracted with 1 ml of 50% EtOH, dried in a vacuum centrifuge, and resuspended in 50 μl of H2O. About 400 cpm of each compound (not UV detectable at 205 nm) was mixed with the authentic nonlabelled standard (UV absorbance of 0.4 at 205 nm) in a total volume of 100 μl and analyzed by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a SuperPac Pep-S column (Pharmacia). HPLC was performed at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with solvent A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile) with the following profile of linear-gradient steps: 5 min, 0% solvent B; 40 min, 20% solvent B; 45 min, 100% solvent B. Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected, and labelled compounds were identified by liquid scintillation counting.

General methods for DNA manipulations.

Standard procedures for DNA analysis were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (22). DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels with the JetSorb Extraction Kit 150 from Genomed. Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli as described by Birnboim and Doly (1); plasmids were isolated from Streptomyces as described by Hopwood et al. (10).

Cosmids and E. coli plasmids.

Cosmids cosA1 and cosP1 are pHC79 derivatives (9) harboring size-fractionated fragments (both 32 kb) of genomic S. chrysomallus DNA obtained after partial Sau3A digestion (19). For restriction analysis, hybridization mappings of peptide synthetase activation domains, and sequencing, various fragments from cosA1 and cosP1 were subcloned in pTZ18 (Pharmacia), pSP72 (Promega), or pSL1180 (Pharmacia). Examples of these strategies are given in the figures and figure legends.

Construction of pACM5 for heterologous expression of acmB.

pACM5 is a derivative of Streptomyces plasmid pIJ702 (11) in which the melC1 gene of the melanine operon (mel) contained by the plasmid is replaced by acmB. The ATG start codon of melC1 is contained in the unique SphI restriction site of the plasmid and was used as an in-frame replacement. To generate a matching SphI site at the start codon of acmB, the translation initiation start (underlined) of acmB (GGTTGAAACGTGTTC) was changed into GGCATGCATATGTTC by PCR. This resulted in two additional amino acids being attached to the amino terminus of the protein (change of MF- to MHMF-). For this modification, we synthesized a 0.5-kb gene fragment by PCR with primer A (5′-ATCGGAGGCATGCATATGTTCGTCCGTCCTGATG-3′) and reverse primer B (5′-TCGGAGTCGCGGTACTTCTGATCGG-3′). Primer A binds to the translational start region of acmB, whereas primer B binds to a sequence located 548 bp downstream of the original GTG start codon. As can be seen from Fig. 1, the fragment encompasses a BglII site at position +50 and a SalI site at position +265 of acmB (not shown). SphI and SalI digestion of the fragment thus resulted in a 265-bp SphI-SalI fragment which was cloned into pTZ18 cleaved with SphI and SalI. This generated plasmid pCR1. Control sequencing verified the correctness of the construct and sequence. Next, a 3.7-kb BglII-BamHI fragment, ranging from the central BglII site in acmB to its next 3′-located BamHI site (outside of acmB) and encompassing the stop codon, was isolated from cosA1 and inserted into BglII-BamHI-cleaved pCR1. The resultant plasmid, pACMΔBg, harbors the engineered 5′ start of acmB fused to the large distal BglII-BamHI fragment in the same orientation as in acmB. This cloned construct (ΔacmB) thus differs from the wild-type acmB in that the central 5.1-kb BglII fragment is deleted and the 5′ end is modified. pACMΔBg was cleaved with SphI and BamHI, and the isolated insert (ΔacmB) was ligated into pIJ702 cleaved with SphI and BglII. After transformation into S. lividans, plasmid pACM3 was obtained. In pACM3, fusion of the BamHI site to the BglII site of the plasmid destroys the BglII site. The missing central 5.1-kb BglII fragment of acmB was isolated from cosA1 and inserted into the unique BglII site of pACM3 (located in ΔacmB), which resulted in pACM5 containing the complete engineered acmB.

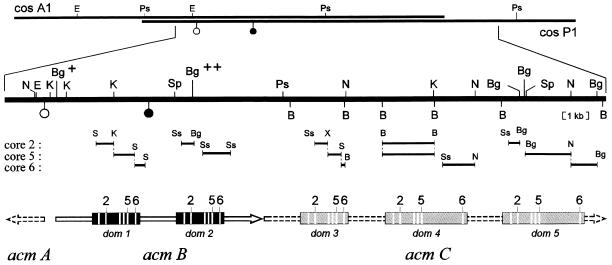

FIG. 1.

Organization of the acm gene cluster. The region of S. chrysomallus DNA, cloned in cosA1 and cosP1, is shown at the top. The section that encompasses the actinomycin synthetase genes is shown enlarged, with all restriction sites of BamHI (B), BglII (Bg), EcoRI (E), KpnI (K), NotI (N), SphI (Sp), and PstI (P) noted. Two BglII sites used for construction of pACM5 are marked (+ and ++). The location of the DNA sequence (5′-ATGGCCGATAAATGGTGGGGGGAACAACTGCTGGGGCGCGGGGACGACGGTGATCTCTGGGCGGTCTCGGCCGCCCCGGTCACCCGGGGCGAGCTCCGCGCC-3′) coding for the N terminus of ACMS I is indicated by an open circle; the position of the sequence (5′-ACGGTGTTCCCCGAGGTCGACGGGACGCCGTACCAGCGG-3′) encoding the tryptic ACMS II fragment (subsequently identified at aa position 1124) is indicated by a solid circle. The mapped regions hybridizing with oligonucleotide probes designed from activation domain cores 2, 5, and 6 are shown below the enlarged section (S, SalI; Ss, SstI; X, XhoI). The ORF of acmB is indicated by a solid arrow, and the segments encoding the two activation domains of ACMS II are drawn as black boxes (dom 1 and 2); white stripes indicate the positions of domain core motifs 1 to 6. Gene acmA and putative gene acmC (dashed arrows) were sequenced partially. Sequencing includes the 5′ region of acmA up to the next EcoRI site and the three indicated fragments of acmC hybridizing with core probe 6. The domain-encoding segments assigned to acmC (dom 3 to 5) are drawn as shaded boxes. They are placed in that manner so that their core motifs fit the core hybridization mapping and are adjusted exactly to the identified localization of motif 6 (shown in Table 1). The indicated core motifs within dom 1 to 3 show the motif arrangement of a highly conserved standard activation domain (600 aa). In contrast, dom 4 and 5 are drawn as enlarged between motifs 5 and 6 to indicate activation domains with additional N-methyltransferase activity, as expected for ACMS III.

Oligonucleotide probes.

Oligonucleotides were designed considering the codon usage of Streptomyces (31). From the N-terminal sequence of ACMS I (ADKWWGEQLLGRGDDGDLWAVSAAPVTRGELRA) (16), oligonucleotide acm1 (5′-TGGGGSGARCAGCTSCTSGGSCGSGGSGACGACGGSGACCTSTGG-3′) was designed. For sequence determination of ACMS II, the protein was purified to homogeneity as described previously (26). The protein was digested with trypsin as described by Stone and Williams (28), and tryptic fragments were isolated by HPLC. The sequence of the tryptic fragment, TVFPEVDGTPYQ(Q)R, was determined by automatic Edman degradation on an ABI gas phase sequencer. From this peptide sequence, oligonucleotide acm2 (5′-ACCGTCTTCCCGGAGGTCGACGGCACCCCGTACCAGCAGCG-3′) was designed. The following digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled oligonucleotides, derived from the consensus sequences of peptide synthetase core motifs 2, 5, and 6 of the activation domain, were kindly provided by S. Pelzer, University of Tübingen, Lehrstuhl für Mikrobiologie und Biotechnologie: core2, 5′-AGGCCTACATCATCTACACCTCCGGCACGACGGGCAAGCCCAAGGG-3′; core5, 5′-CAGGTCAAGATCCGCGGCTACCGCATCGAGCTCGGCGAGATCGAG-3′; and core6, 5′-CTCGGCGGGCACTCCCTCAAGGCCT-3′.

DNA hybridization analysis.

Oligonucleotides were diluted to about 100 ng/ml when used as probes for Southern analysis. Nucleic acids were transferred to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham) with 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and immobilized by UV cross-linking. For cosmid screening, E. coli colonies were transferred to membranes and DNA was released by alkaline treatment. Cosmid filters were hybridized with 3′ 32P-labelled oligonucleotides (acm1 and acm2) at 65°C (in a solution containing 5× SSC, 0.02% SDS, 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 1% blocking solution; Boehringer kit 1175041) and washed with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C. Cosmids hybridizing with labelled probes were detected by autoradiography (film NIF100; Konica). Southern analysis with domain core probes was performed at 40°C, both for hybridization (20 h) and wash steps (twice for 30 min), with DIG nucleic acid detection kit 1175041 from Boehringer Mannheim. DIG-labelled nucleotides were detected with the anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate supplied with the kit at 25°C for 20 to 30 min.

DNA sequencing analysis and computer analysis.

The sequence of the acmB gene was determined with various fragments isolated from cosmid cosA1 and subcloned in pTZ18. The region between acmA and the single SphI site in acmB (see also Fig. 1) was determined by Taq cycle sequencing (U.S. Biochemicals-Amersham sequencing kit US71001 or US78500) with universal oligonucleotide primers. The remaining part of acmB was sequenced by Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium) by primer walking with dye-labelled dideoxy terminators (Applied Biosystems; model 377). Sequence comparisons, multiple sequence alignments, and identity scores were computed with CLUSTAL V (8).

Radioisotopes and chemicals.

l-[U-14C]threonine (208 Ci/mol, 100 μCi/ml) and l-[U-14C]valine (283 Ci/mol, 100 μCi/ml) were from DuPont. Authentic dipeptides used as standards for HPLC analysis were either from Bachem (l-Thr–l-Val) or were synthesized (l-Thr–d-Val) as described previously (27). The identity of l-Thr–d-Val was verified by mass spectrometry and amino acid analysis after acid hydrolysis.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence obtained in this study has been assigned GenBank accession no. AF047717.

RESULTS

Molecular cloning of the actinomycin (acm) gene cluster.

Genes for antibiotic biosynthesis in streptomycetes are usually clustered. A previous genetic analysis of mutants for actinomycin biosynthesis indicated a similar situation for the acm genes in S. chrysomallus (6). Nonpleiotropic acm mutations fell into one linkage group and were mapped to one interval of the S. chrysomallus chromosome. However, in all of the mutants the three ACMSs were present and most mutants were impaired in the production of antibiotic precursor 4-MHA (6). Since none of the mutants was suitable for cloning the peptide synthetase genes by complementation, we isolated these genes by screening a cosmid library of S. chrysomallus with oligonucleotides derived from protein sequences of ACMSs. Purified ACMS II was digested with trypsin, and from the peptide sequence of one tryptic ACMS II fragment [TVFPEVDGTPYQ(Q)R] oligonucleotide probe acm2 was designed. Hybridization screening with acm2 led to the isolation of two overlapping cosmids (cosA1 and cosP1) comprising a total stretch of 42 kb of genomic S. chrysomallus DNA as shown in Fig. 1. A second oligonucleotide probe, acm1, derived from the amino-terminal sequence of ACMS I (ADKWWGEQLLGRGD DGDLWAVSAAPVTRGELRA) (16), hybridized also with cosmids cosA1 and cosP1. This indicated that both actinomycin synthetase genes are located in the overlapping region of these cosmids. Detailed restriction analysis and hybridization mapping revealed that probe acm1 hybridized to a 0.6-kb EcoRI-KpnI fragment and that probe acm2 hybridized to a 2.2-kb KpnI-SphI fragment. These fragments were further analyzed, and two DNA sequences were identified (see the legend for Fig. 1); the deduced amino acid sequences matched exactly with the two corresponding ACMS peptide sequences (with only one glutamine in the tryptic ACMS II sequence shown above).

Organization of the acm gene cluster.

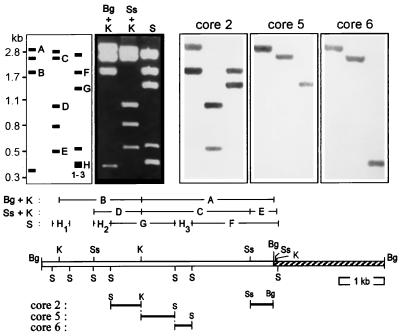

The DNA sequence coding for the N terminus of ACMS I was localized on a 0.6-kb EcoRI-KpnI fragment, which allowed the mapping of the start and the orientation of the corresponding gene (acmA), as shown in Fig. 1. In order to locate the two expected activation domain-encoding regions of the ACMS II gene (acmB) and to see if there are any additional such regions on cosmids cosA1 and cosP1, combined restriction/hybridization mappings were performed with three different oligonucleotide probes, based on consensus signature sequences of peptide synthetase activation domains (cores 2, 5 [amino acid adenylation], and 6 [thioester formation]) (24, 25, 30). Sequence analyses of a number of acyl-adenylating enzymes have shown that their core motif sequences are less conserved than those in peptide synthetase domains. Therefore acmA was not expected to hybridize with any of these core probes under stringent conditions. In fact, these oligonucleotides hybridized to the region upstream of acmA but not to acmA itself or to its downstream-located region. An example of the core hybridization analysis, performed with a plasmid carrying the 5.1-kb BglII fragment upstream of acmA, is shown in Fig. 2. Three probes hybridized to three adjacent regions on the left side of the fragment in the motif order 2, 5, and 6. This order fits with the arrangement of the corresponding cores in a peptide synthetase activation domain (24). A fourth signal, seen with the core 2 probe, indicates the proximal portion of the next domain-encoding segment at the right site of the fragment. Extending this kind of mapping analysis to the whole cloned region upstream of acmA led to the detection of a total of five putative activation domain-encoding segments (dom 1 to 5; summarized in Fig. 1). These segments are separated from each other by more than 1 kb and are arranged in the same orientation, which is implied by the motif order of the hybridizing regions. The first two domain-encoding segments, dom 1 and dom 2, were analyzed in the course of sequencing acmB (see below); for dom 3 to 5 only the fragments hybridizing with core probe 6 (indicated in Fig. 1) were sequenced. All five segments were found to encode motif 6, which is the 4′-phosphopantetheine attachment site of peptide synthetases (see Table 1), and the missing hybridization signal of core probe 6 with segment dom 2 turned out to be only the result of less-conserved DNA sequence similarity. The presence of five domain-encoding segments arranged in the same orientation would be in agreement with the enzymatic activities of ACMS II and ACMS III, which activate two and three amino acids, respectively. The DNA sequence encoding the tryptic ACMS II peptide (TVFPEVDGTPYQR) was mapped on the 2.2-kb KpnI-SphI fragment between dom 1 and dom 2, which implies that acmB spans these two domain-encoding segments. The region spanning segments dom 3 to 5 probably contains the gene coding for ACMS III (480 kDa) with an estimated size of about 13 kb (acmC).

FIG. 2.

Hybridization mapping of domain cores. Restriction fragments of plasmid pA1sub11, which is a pSP72 derivative carrying the 5.1-kb BglII fragment upstream of acmA (indicated by + and ++ in Fig. 1) in the BglII site of the pSP72 polylinker, were separated on a 1% agarose gel (second panel from left; Bg, BglII; K, KpnI; S, SalI; Ss, SstI). Fragments were analyzed by Southern hybridization with DIG-labelled oligonucleotides designed from domain cores (motifs 2, 5, and 6; right three panels) as described in Materials and Methods. The Southern filters were prepared from three identical agarose gels (only one is shown) and hybridized exclusively with the indicated core probe to exclude the remains of previous stainings. The fragment pattern is schematically shown in the left panel, and all hybridizing fragments are indicated by letters A to H (three SalI fragments of the same size [only one is hybridizing] are labelled 1-3). These fragments are aligned above the restriction map of pA1sub11 (the pSP72 portion is striped), which allows the mapping of the hybridizing regions for every core probe, as shown below the plasmid map.

TABLE 1.

Identified motifs for 4′-phosphopantetheine cofactor attachment

Sequencing the ACMS II gene (acmB).

Sequencing the region upstream of acmA revealed the presence of an open reading frame (ORF) of 7,833 bp starting 430 bp from the start codon of acmA and in the opposite orientation. The ORF shows the typical Streptomyces codon usage (31), with a 94% G+C content in the third codon position and an overall G+C content of 73%. The deduced protein has a size of 283.9 kDa, which fits well with the estimated size of ACMS II of 280 kDa (26). It contains two amino acid activation domains (schematically indicated in Fig. 1), as revealed by a sequence comparison with a number of peptide synthetase sequences (data not shown). The activation domain core motifs (motifs 1 to 6) (24), essential for ATP binding, amino acyladenylate formation, and covalent attachment of the 4′-phosphopantetheine cofactor, are located between amino acids (aa) 534 and 1015 in the first domain and between aa 1603 and 2064 in the second one. Four characteristic motifs for the epimerization function of peptide synthetases (motifs A to D) (24) are located in the C-terminal region distal to the second domain (between aa 2359 and 2493). This fits with the observed epimerization activity of ACMS II. A motif, which is thought to play a role in the peptide elongation reaction and/or acyl transfer (His motif or spacer motif) (3, 24), precedes both activation domains (at aa 140 and 1196), and a third His motif, thought to play a role in epimerization domains, is about 110 amino acids in front of the epimerase motifs (at aa 2250). This is in accordance with the established reaction mechanism of ACMS II in forming 4-MHA–threonine and 4-MHA–threonyl–d-valine (from the l-valine-containing diastereomer).

Functional expression of acmB.

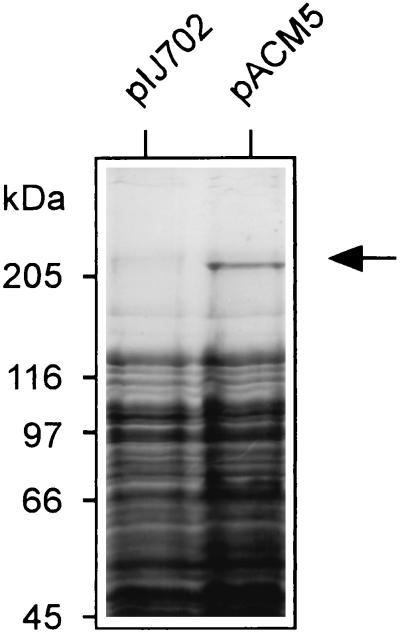

From a sequence analysis of acmB, the encoded protein was predicted to catalyze dipeptide formation and epimerization of the C-terminal amino acid. To demonstrate these activities, acmB was heterologously expressed in S. lividans. The 5′ end of acmB was engineered by PCR for expression from the mel promoter in Streptomyces plasmid pIJ702, as described in Materials and Methods. In the final construct, pACM5, acmB is inserted as an in-frame fusion to the ATG start codon of the melC1 gene. In this construct, the recombinant ACMS II has two additional amino acids fused to the N terminus. S. lividans transformants harboring pACM5 did not produce melanine and were analyzed for the presence of engineered ACMS II. In crude extracts of these transformants, a protein in the range of 240 to 300 kDa, which was not seen in control strains harboring pIJ702, was detected (Fig. 3). After ammonium sulfate precipitation and gel filtration, protein fractions were tested for binding amino acid substrates as thioesters. Fractions containing the pACM5-encoded protein were able to form thioesters with threonine and valine (fractions 14 to 19 in Fig. 4), which are established substrates for ACMS II (13, 26). In a control experiment with proline, which is a substrate only for ACMS III, no thioester formation was detected (data not shown). Furthermore, in protein fractions of a control strain transformed with pIJ702 thioester formation was not detected either with threonine or with valine (data not shown). These results indicate that thioester formation detected in transformants harboring plasmid pACM5 is correlated with the presence of the engineered ACMS II.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis of engineered ACMS II expressed from pACM5 in S. lividans. Cells harboring plasmid pIJ702 (control) or pACM5 (expression of acmB) were grown as described in Materials and Methods and broken by sonification. Proteins of total crude extracts were separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue. The arrow indicates ACMS II.

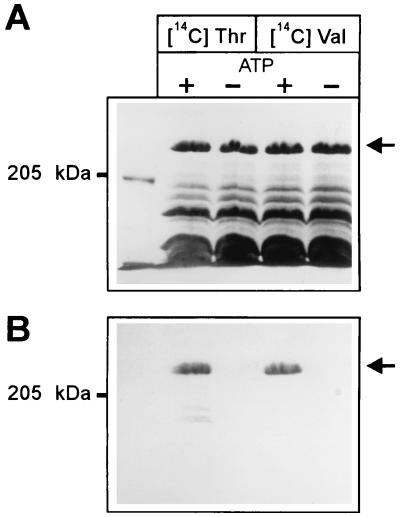

To clearly assign thioester formation to the plasmid-encoded synthetase, protein fractions showing this activity were analyzed by SDS-PAGE after incubation with labelled substrates (Fig. 5A). Both radioactive amino acids, threonine and valine, clearly labelled the engineered ACMS II in an ATP-dependent fashion (Fig. 5B). The 4′-phosphopantetheine content of the enzyme was not determined.

FIG. 5.

Amino acid substrates covalently bound to engineered ACMS II as thioesters. (A) Coomassie blue-stained 4% polyacrylamide gel of Ultrogel-AcA-34-purified ACMS II after incubation with [14C]threonine (left) or [14C]valine (right) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of ATP as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Autoradiograph of the gel shown in panel A.

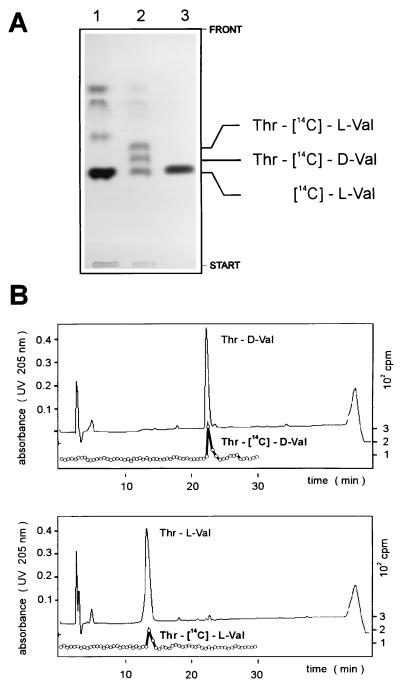

To address the additional functions of the synthetase, such as peptide bond formation and peptide epimerization, the FPLC-purified enzyme was incubated with [14C]valine and unlabelled threonine in the presence of ATP. After completion of the reaction, enzyme-bound material was isolated and separated by TLC (Fig. 6A). In the presence of both substrate amino acids (Fig. 6A, lane 2) two new additional compounds, which were not seen with valine alone were detected (Fig. 6A, lane 1). In previous investigations with ACMS II isolated from S. chrysomallus, a similar formation of two compounds with Rf values slightly higher than those of valine was observed; the two compounds have been identified as Thr–l-Val and Thr–d-Val (27). To demonstrate that the products synthesized by plasmid-encoded ACMS II are identical to Thr–l-Val and Thr–d-Val, the two compounds were further analyzed by HPLC and compared with corresponding nonlabelled standards (Fig. 6B). HPLC analysis clearly shows that the engineered ACMS II is able to catalyze the formation of a threonyl–l-valine dipeptide, which is epimerized to threonyl–d-valine.

FIG. 6.

Formation of threonyl–l-valine and threonyl–d-valine catalyzed by engineered ACMS II. (A) Reaction intermediates from thioester formation, covalently bound to ACMS II, were cleaved off with performic acid and analyzed on TLC silica plates as described in Materials and Methods. Thioester formation was performed with l-[14C]valine (lane 1) or with l-[14C]valine in the presence of unlabeled l-threonine (lane 2). The reference was l-[14C]valine (lane 3). Labeled compounds were identified by autoradiography. (B) The two compounds, expected to be Thr–d-[14C]Val and Thr–l-[14C]Val were isolated from the silica plate shown in panel A and analyzed by HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. About 400 cpm of each compound (not UV detectable) was mixed with an unlabeled reference dipeptide (UV detection at 205 nm).

DISCUSSION

Actinomycin half molecules (4-MHA pentapeptide lactones) are assembled by two peptide synthetases (ACMS II and III) in conjunction with a 4-MHA–adenylate ligase (ACMS I). By using oligonucleotides derived from partial peptide sequences of ACMS I and II we cloned a gene cluster from S. chrysomallus containing the corresponding genes acmA and acmB, respectively. Sequencing acmB revealed that it codes for a peptide synthetase of 284 kDa with two amino acid activation domains and one epimerization domain. A hybridization analysis with oligonucleotide probes coding for signature sequences of peptide synthetase activation domains indicated the presence of a further peptide synthetase gene with three domain-encoding segments downstream of acmB (Fig. 1). Since ACMS II incorporates the first two amino acids of the 4-MHA pentapeptide lactone and ACMS III incorporates the remaining three, this second peptide synthetase gene most probably is the gene encoding ACMS III (acmC).

Heterologous expression of acmB in S. lividans yielded a functionally active peptide synthetase specifically activating l-threonine and l-valine as thioesters. Moreover, it catalyzed the formation of the threonyl–l-valine and threonyl–d-valine dipeptides, as does ACMS II from S. chrysomallus. These catalytic activities are in agreement with the sequence data and leave little doubt that the acmB gene product is ACMS II. The ACMS II sequence showed the greatest similarity to pristinamycin I synthetase C (SnbC) from Streptomyces pristinaespiralis (2) (50% identity over the complete sequence of the two enzymes). Pristinamycin I, an acyl hexapeptide lactone belonging to the group of the mikamycin B antibiotics, has striking structural similarity to the actinomycin half molecules (18, 23). Instead of 4-MHA, mikamycin B antibiotics contain 3-hydroxypicolinic acid as an acyl side group. However, from the number and similarity of amino acid residues in their hexa- or heptapeptide lactone rings, mikamycin B antibiotics can be regarded as elongated versions of the 4-MHA pentapeptide lactone structure (23). It was suggested that aromatic acyl peptide lactones such as the mikamycins and the actinomycin half molecules are synthesized by similar sets of enzymes (5, 14, 16, 23). In fact, Thibaut et al. (29) recently showed that pristinamycin I is also synthesized by three synthetases, SnbA, SnbC, and SnbD. By comparison, these have been postulated to function like their corresponding ACMS I, II, and III analogs except that SnbD activates four amino acids compared to the three activated by ACMS III. The sequence similarity between ACMS II and SnbC is thus consistent with the similar roles of the two enzymes, i.e., activation of the first two amino acids of the peptide lactone rings, acyl dipeptide formation, and epimerization.

The results of previous biochemical investigations of 4-MHA–threonine and 4-MHA–threonyl–ld-valine formation catalyzed by ACMS II in conjunction with ACMS I suggested that 4-MHA is covalently bound as a thioester to a phosphopantetheine cofactor presumed to reside on ACMS II. However, inspection of the sequence of ACMS II presented here revealed only two 4′-phosphopantetheine attachment sites in the protein sequence (one in the threonine activation domain and the other in the valine activation domain). This may point to an additional factor providing the missing third 4′-phosphopantetheine cofactor required for the formation of the 4-MHA–Thr peptide bond. This factor could have escaped detection in enzyme preparations due to low concentration or small size. Interestingly, Gehring et al. (4) characterized an as yet unsuspected acyl carrier domain as a component of the enterobactin biosynthesis system in E. coli. Enterobactin is a cyclic trilactone composed of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl–serine (2,3-DHB–serine) units. The 2,3-DHB–serine unit is assembled by enzymes EntE and EntF (20, 21), which have been suggested to function in a manner similar to that of ACMS I and II or SnbA and SnbC in the formation of 4-MHA–threonine or 3-hydroxypicolinic acid–threonine. The respective acyl carrier domain is part of isochorismate lyase (EntB) involved in 2,3-DHB synthesis and was shown to be pantetheinylated by a specific enzyme. Interestingly, EntE activates 2,3-DHB as adenylate and acylates EntB with 2,3-DHB. Gehring et al. (4) postulate that the thioester-bound 2,3-DHB residue is subsequently transferred from EntB to the amino group of serine covalently bound to the 4′-phosphopantheine arm of EntF, yielding 2,3-DHB–serine. A similar mechanism for the initiation of actinomycin half-molecule synthesis is imaginable if a comparable acyl carrier protein would interact with ACMS I and II. To clarify the exact mechanism, more detailed investigations, both on the enzymatic and genetic levels, have to be performed. The in vitro studies presented have shown that heterologous expression of the ACMS II gene yielded a synthetase which maintained its specific activities, not only with respect to amino acid activation but also with respect to dipeptide formation and epimerization. This important finding and the successful cloning of the acm gene cluster should provide the future basis to investigate ACMS interactions by a stepwise rebuilding of the system in a heterologous host and to get more insight into the mechanism of acyl peptide lactone synthesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stefan Pelzer for kindly providing the oligonucleotides derived from the signature sequences of peptide synthetase domains. We thank S. Lucania from Bristol-Myers-Squibb for the gift of thiostrepton.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant Ke 452/8-2).

REFERENCES

- 1.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Crécy-Lagard V, Blanc V, Gil P, Naudin L, Lorenzon S, Famechon A, Bamas-Jaques N, Crouzet J, Thibaut D. Pristinamycin I biosynthesis in Streptomyces pristinaespiralis: molecular characterization of the first two structural peptide synthetase genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:705–713. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.705-713.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Crécy-Lagard V, Marlière P, Saurin W. Multienzymatic non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis: identification of the functional domains catalyzing peptide elongation and epimerization. C R Acad Sci. 1995;318:927–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gehring A M, Bradley K A, Walsh C T. Enterobactin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: isochorismate lyase (EntB) is a bifunctional enzyme that is phosphopantetheinylated by EntD and then acylated by EntE using ATP and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8495–8503. doi: 10.1021/bi970453p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glund K, Schlumbohm W, Bapat M, Keller U. Biosynthesis of quinoxaline antibiotics: purification and characterization of the quinoxaline-2-carboxylic acid activating enzyme from Streptomyces triostinicus. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3522–3527. doi: 10.1021/bi00466a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haese A, Keller U. The genetics of actinomycin C production in Streptomyces chrysomallus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1360–1368. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1360-1368.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of E. coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1985;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins D G, Bleasby A J, Fuchs R. CLUSTAL V: improved software for multiple sequence alignment. CABIOS. 1991;8:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hohn B, Collins J. A small cosmid for efficient cloning of large DNA fragments. Gene. 1980;11:291–298. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces. A laboratory manual. Norwich, England: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz E, Thompson C J, Hopwood D A. Cloning and expression of the tyrosinase gene from Streptomyces antibioticus in Streptomyces lividans. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2703–2714. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-9-2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller U. Acyl pentapeptide lactone synthesis in actinomycin-producing streptomycetes by feeding with structural analogs of 4-methyl-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (4-MHA) J Biol Chem. 1984;259:8226–8231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller U. Actinomycin synthetases: multifunctional enzymes responsible for the synthesis of the peptide chains of actinomycin. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5852–5856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller U. Peptidolactones. In: Vining L C, Stuttard C, editors. Genetics and biochemistry of antibiotic production. Toronto, Canada: Heinemann-Butterworths Publisher; 1995. pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller U, Kleinkauf H, Zocher R. 4-Methyl-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (4-MHA) activating enzyme from actinomycin producing Streptomyces chrysomallus. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1479–1484. doi: 10.1021/bi00302a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller U, Schlumbohm W. Purification and characterization of actinomycin synthetase I, a 4-methyl-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid: AMP ligase from Streptomyces chrysomallus. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11745–11752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinkauf H, von Döhren H. Nonribosomal biosynthesis of peptide antibiotics. Eur J Biochem. 1990;192:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okumura Y. Peptidolactones. In: Vining L C, editor. Biochemistry and genetic regulation of commercially important antibiotics. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1983. pp. 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pahl A, Ühlein M, Schlumbohm W, Bang H, Keller U. Streptomycetes possess peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases that strongly resemble cyclophilins from eukaryotic organisms. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3551–3558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rusnak F, Faraci W S, Walsh C T. Subcloning, expression, and purification of the enterobactin biosynthetic enzyme 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate-AMP ligase: demonstration of enzyme-bound (2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)adenylate product. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6827–6835. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rusnak F, Sakaitani M, Drueckhammer D, Reichert J, Walsh C T. Biosynthesis of the Escherichia coli siderophore enterobactin: sequence of the entF gene, expression and purification of EntF, and analysis of covalent phosphopantetheine. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2916–2927. doi: 10.1021/bi00225a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlumbohm W, Keller U. Chromophore activating enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of the mikamycin B antibiotic etamycin from Streptomyces griseoviridus. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2156–2161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stachelhaus T, Marahiel M A. Modular structure of genes encoding multifunctional peptide synthetases required for non-ribosomal peptide synthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;125:3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein T, Vater J, Kruft V, Wittmann-Liebold B, Franke P, Panico M, Dowell R M, Morris H R. Detection of 4′-phosphopantetheine at the thioester binding site for l-valine of gramicidin S synthetase 2. FEBS Lett. 1994;340:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stindl A, Keller U. The initiation of peptide formation in the biosynthesis of actinomycin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10612–10620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stindl A, Keller U. Epimerization of the d-valine portion in the peptide chain of actinomycin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9358–9364. doi: 10.1021/bi00197a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stone K L, Williams K R. Enzymatic digestion of proteins and HPLC peptide isolation. In: Matsudaira P, editor. A practical guide to protein and peptide purification for microsequencing. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 43–69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thibaut D, Bisch D, Ratet N, Maton L, Couder M, Debusche L, Blanche F. Purification of peptide synthetases involved in pristinamycin I biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:697–704. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.697-704.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turgay K, Krause M, Marahiel M A. Four homologous domains in the primary structure of GrsB are related to domains in a superfamily of adenylate-forming enzymes. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:529–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright F, Bibb M J. Codon usage in the G+C rich Streptomyces genome. Gene. 1992;113:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90669-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuber P, Marahiel M A. Structure, function, and regulation of genes encoding multidomain peptide synthetases. In: Strohl W R, editor. Biotechnology of antibiotics. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Marcel Decker, Inc.; 1997. pp. 187–216. [Google Scholar]