Abstract

Background:

Sleep disturbances are common among adult patients with cancer and their caregivers. To our knowledge, no sleep intervention to date has been designed to be provided to both cancer patients and their caregivers simultaneously. This single arm study aimed to pilot test the feasibility and acceptability, and to illustrate the preliminary efficacy on sleep efficiency of the newly developed dyadic sleep intervention, My Sleep Our Sleep (MSOS: NCT04712604).

Methods:

Adult patients who were newly diagnosed with a gastrointestinal cancer and their sleep-partner caregivers (n= 20 persons: 10 dyads, 64 years old, 60% female patients, 20% Hispanic, 28 years relationship duration), both of whom had at least mild levels of sleep disturbance (PSQI≥ 5) participated. MSOS intervention consists of four 1-hour weekly sessions delivered using Zoom to the patient-caregiver dyad together.

Results:

We were able to enroll 92.9% of the eligible and screened patient-caregiver dyads within 4 months. Participants reported high satisfaction in 8 domains (average 4.76 on a 1–5 rating). All participants agreed that the number of sessions, interval (weekly), and delivery mode (Zoom) were optimal. Participants also preferred attending the intervention with their partners. Both patients and caregivers showed improvement in sleep efficiency after completing the MSOS intervention: Cohen’s d= 1.04 and 1.47, respectively.

Conclusions:

Results support the feasibility and acceptability, as well as provide the preliminary efficacy of MSOS for adult patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their sleep-partner caregivers. Findings from this study suggest the need for more rigorous controlled trial designs for further efficacy testing of MSOS intervention for medical populations.

Keywords: Dyadic sleep intervention, adult patients with cancer, caregivers, sleep efficacy

Introduction

Sleep disturbance—defined as difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and frequent and prolonged nighttime awakenings (National Institutes of Health, 2011; Berger, 2009)—is highly prevalent (33%−40%) among adult patients with cancer across all cancer sites/types and cancer trajectory, notably more so than a 15%−20% seen in the general population (Berger, 2009; Harris et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2004). Sleep disturbance in patients with cancer have further been associated with poor quality of life, circadian dysregulation, development of major diseases, poor cancer prognosis and recurrence, and mortality (Berger, 2009; Cappuccio et al., 2010; Cohen-Mansfield & Perach, 2012; Gangwisch et al., 2007; Irwin, 2015; Knutson, 2010; Kudlow et al., 2013; Phillips et al., 2017; Stevens et al., 2014; Troxel, 2010; Watanabe et al., 2010).

Sleep disturbance is also highly prevalent among family members who provide support to their relatives with cancer (hereafter caregivers). For example, 36%−95% of family caregivers report sleep disturbance by self-report or objective assessment, and 4 in 10 report at least one sleep problem (Dhruva et al., 2012; Kotronoulas et al., 2013). These rates and severity are higher than those in caregivers of patients with other diseases, such as AIDS and dementia (Kochar et al., 2007; Medic et al., 2017; Mills et al., 2009; Spira et al., 2010), chronic knee osteoarthritis (Martire et al., 2013), Parkinson’s disease (Happe et al., 2002; Pal et al., 2004), and stroke (Rittman et al., 2009), as well as those seen among patients with dementia (Flaskerud, Carter, & Lee, 2000) and in demographically similar healthy adults (Mills et al., 2009). Caregivers’ sleep disturbance degrades the quality of care they provide for the patients, decreases their own quality of life (Irwin, 2015; Katz & McHorney, 2002), and increases their own risk for various morbidities (Berger, 2009; Cappuccio et al., 2010; Cohen-Mansfield & Perach, 2012; Gangwisch et al., 2007; Irwin, 2015; Knutson, 2010; Kudlow et al., 2013; Phillips et al., 2017; Stevens et al., 2014; Troxel, 2010; Watanabe et al., 2010).

The empirical evidence underscores the need for sleep interventions for patients with cancer and their family caregivers. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is a gold standard psychobehavioral intervention endorsed by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for treating sleep disturbance/insomnia in the general population (Bootzin & Epstein, 2011). CBT-I has since been modified to address the unique experiences of sleep disturbance in patients with cancer. For example, decreasing the number of CBT-I sessions for patients with cancer from 6–8 to 2–4 or administering the intervention using a stepped care model has been found to be efficacious (Savard et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020). Modified CBT-I for patients with cancer also de-emphasizes sleep restriction, reflecting common characteristics of sleep disturbance seen in adult patients with cancer (Johnson et al., 2016; Palesh et al., 2012; Palesh et al., 2020; Savard et al., 2021). The common characteristics of poor sleep between patients with insomnia and patients with cancer, however, have been kept in modified CBT-Is for patients with cancer. The efficacy of modified CBT-I for cancer patients in comparison with standard CBT-I has been cumulating in recent years (Johnson et al., 2016; Palesh et al., 2012; Palesh et al., 2020; Savard et al., 2021).

Although the efficacy of the modified CBT-I for adult patients with cancer has recently begun cumulating (Johnson et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2021; Savard et al., 2021), only one intervention study, to date, has targeted improving sleep quality for caregivers of adult patients with cancer. This intervention included stimulus control, relaxation, cognitive therapy, and sleep hygiene elements and was found to be effective in improving sleep quality and decreasing depressive symptoms in caregivers (Carter, 2006).

The social support literature suggests possible broad pathways from social support to better sleep. Social support protects against social isolation (Cacioppo et al., 2002; Pressman et al., 2005), attenuates stress responses (Morin et al., 2003; Troxel et al., 2007), provides a sense of belonging and emotional support (Gunn & Eberhardt, 2019; Troxel et al., 2007), encourages healthy sleep behaviors, and entrains circadian rhythms (Monk et al., 2004). This line of thought suggests that couples’ relationship function and their sleep reciprocally affect each other via their shared psychobiological processes (Irwin, 2015). This conceptual framework provides a basis for dyadic investigation of sleep and sleep disturbance, which thus far has been applied only to healthy young-to-middle-aged adults (Gunn et al., 2017; Gunn et al., 2021; Hasler & Troxel, 2010; Kane et al., 2014; Segrin & Burke, 2015; Troxel et al., 2007; Walters, Phillips, Boardman, et al., 2020), patients with insomnia (Mellor et al., 2019; Walters, Phillips, Mellor, et al., 2020), or parents with newborn babies (Feinberg et al., 2016; Sadeh et al., 2011), whose sources of sleep disturbance exclusively differ from those in cancer patient-caregiver dyads.

Patients with cancer are at risk for sleep disturbance due in part to cancer-related distress and treatment-related cytokine-induced inflammation (Liu et al., 2012). Some sleep-partner caregivers are also at risk by sharing the cancer-related stress and possibly engaging in regulatory processes that compromise not only their sleep quality but also the sleep-partner’s. On the other hand, one member in the dyad may serve as an anchor to protect both themselves and their partners against disturbed sleep by engaging in sleep regulatory processes that enhance not only their sleep quality but also the sleep-partner’s. Intervening on both sleep partners who serve as each other’s comrade to make desirable changes, as opposed to intervening on a sole member in the dyad or each member individually, is an optimal strategy that is highly likely to yield larger impact on improving sleep and general health. It would be particularly the case among at-risk dyads of adult patients with cancer and their sleep partners. Thus, this study pilot tested the feasibility and acceptability, and demonstrated the preliminary efficacy of a newly developed dyadic sleep intervention for adult patients with cancer and their sleep-partner caregivers.

Methods

Participants

Couples consisting of patients with gastrointestinal (GI) cancer and their sleep-partner family caregiver were recruited at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center clinics in South Florida. Eligibility criteria for patients were having a diagnosis of stage I to IV of a GI cancer (anus, colon, esophagus, gallbladder, large and small intestine, liver, pancreas, rectum, stomach, other biliary or digestive organs) in the past 5 years at the time of enrollment and having a consistent sleep partner. Eligibility criterion for caregivers was being a sleep partner of the patient. Additional eligibility criteria for both patients and caregivers included having at least mild-to-moderate sleep disturbance (PSQI ≥ 5; Buysse et al., 1989), willing to change sub-optimal sleep habits, 18 years or older, able to speak and read English, and if applicable, > 4 weeks after surgery prior to enrollment because surgery affects sleep. Exclusion criteria for both patients and caregivers were having had a diagnosis of psychosis, major depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder that was not being treated; substance or alcohol dependency, or active suicidality in the past year; have narcolepsy or restless leg syndrome; have an extreme chronotype, or do shift work such that there is no overlap in sleep schedule between patients and caregivers; plan trans-meridian travel during the period of data collection; and have hearing or visual impairment, dementia, or cognitive dysfunction.

Procedure

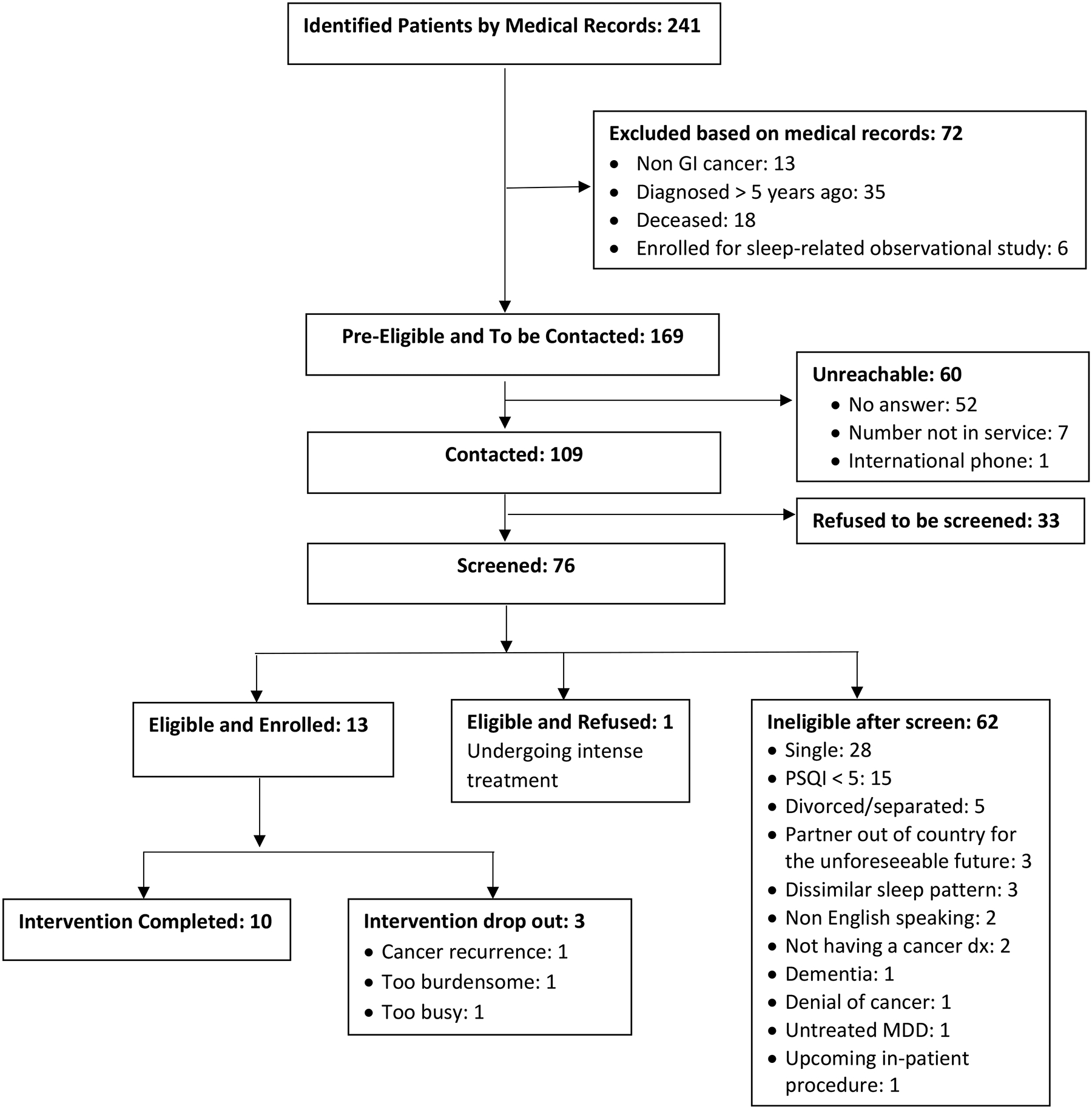

This study was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Boards. The protocol was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04712604). As shown in Figure 1, potentially eligible patients were identified by their diagnosis of a GI cancer and diagnosis date, using medical records at oncology clinics. Pre-eligible patients by the medical records were contacted and screened for eligibility to participate in the study. Participants who were eligible and agreed to participated in the study signed an informed consent form individually on a web-based REDCap application before providing any study data. Participants (patient and caregiver as a unit) participated in the study together; the data were collected simultaneously from both members of the dyad individually. Data were collected from March 2021 to July 2021.

Figure 1.

MSOS Enrollment Flowchart

Participants completed the pre-intervention assessment (T1), which included a one-time questionnaire on a web-based Qualtrics survey application and a 7-day daily sleep measure on a web-based REDCap application. This study employed a single-arm study design. The intervention was delivered via a HIPAA-compliant Zoom video platform once a week to both patients and caregivers together for 4 weeks. Participants completed an intervention satisfaction survey immediately after the end of each session on a web-based Qualtrics survey application. Project coordinator managed the intervention satisfaction survey, so that participants were informed that the interventionist was blind to the survey data. Seven days after the final intervention session, participants completed the post-intervention assessment (T2) that included another one-time questionnaire and another 7-day daily sleep measure on a web-based Qualtrics survey and REDCap application, respectively (see Kim et al., manuscript under review, for more details). Participating dyads were provided a $20 incentive at the end of the study.

Measures

Daily Sleep Assessment.

Participants completed a sleep diary each morning for 7 consecutive days using a modified Consensus Sleep Diary (Carney et al., 2012). The sleep diary includes entries for bedtime, sleep onset, number and duration of awakenings, sleep offset, out-of-bed time, naps, physical activity, and caffeine or alcohol intake, from which sleep hygiene behaviors were assessed. The sleep diary also includes questions about the sleep environment and behaviors in the bed, from which stimulus control behaviors were assessed. The sleep diary data collected during the pre-intervention block served to tailor the behavioral module of the dyadic sleep intervention. Sleep efficiency derived from the sleep diary assessments at pre- and post-intervention blocks served as the primary outcome.

Questionnaire

Questionnaire included three types of measures and demographic questions. One set of measure was to assess overall sleep disturbance. Subjective sleep quality and general sleep disturbance was assessed using the 19-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) at T1 and T2 (Buysse et al., 1989). Higher scores of overall sleep disturbance (range 0–21) and subjective sleep quality (range 0–3) indicate greater sleep disturbance and poorer sleep quality. The overall sleep disturbance score served as an eligibility criterion. Subjective sleep quality score served as a secondary outcome.

A second measure assessed dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep at T1 and T2 using the 16-item Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep (DBAS; Morin et al., 2007) on an 11-point Likert type format (0: strongly disagree, 10: strongly agree). The total and subscale (5-item consequence, 6-item worry, 2-item sleep expectations, and 3-item sleep medication) scores of the DBAS served to tailor the cognition module of the dyadic sleep intervention for individual participants. The DBAS total and subscale scores had acceptable internal consistency in the present study at T1 (.76 < α < .84 for patients and .65 < α < .86 for caregivers), with the exception of the expectations subscale (α= .42, r between the 2 items = .26, p= .46 for patients; and α= .35, r between the 2 items = .27, p= .44 for caregivers) and the medications subscale (α= .51 for patients; and α= .50 for caregivers). The DBAS total and subscale scores remained to have acceptable internal consistency in the present study at T2 (.77 < α < .87 for patients and .58 (consequences) < α < .91 for caregivers), again with the exception of the expectations subscale (α= .40, r between the 2 items = .251, p= .48 for patients; and α= .53, r between the 2 items = .40, p= .26 for caregivers) and the medications subscale (α= .50 for patients; and α= .52 for caregivers).

A third measure was used to assess relationship quality at T1, which included the 14-item Measures of Attachment Quality (MAQ; Carver, 1997) that assesses three adult attachment orientations: security, anxiety, and avoidance; and the 4-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Sabourin et al., 2005) that assesses relationship satisfaction. The three attachment orientation and relationship satisfaction composite scores had overall acceptable internal consistency in the present study (.67 < α < .93 for patients and .56 (anxiety) < α < .89 for caregivers). The MAQ and DAS scores served to tailor the relationship module of the dyadic sleep intervention. Finally, demographic questions included self-reported age, gender, education, income, race/ethnicity, and relationship duration.

Dyadic Sleep Intervention.

My Sleep Our Sleep (MSOS: NCT04712604) consists of four 1-hour weekly sessions that were delivered via HIPAA-compliant Zoom video platform. The MSOS intervention was developed by (a) adapting the behavioral (sleep hygiene and stimulus control) and cognitive (monitoring and managing maladaptive thoughts about sleep) modules of CBT-I, for adult patients with cancer by relaxing sleep restriction, (b) accommodating the symptoms and experience of cancer and treatment that are attributable to their disturbed sleep, (c) targeting both sleep partners, and (d) educating sleep partners about relationship-enhancing communication and working together effectively to sleep well. In addition, the MSOS intervention acknowledged the significant close relationship nature of sleep and cancer experience. These principles adapting CBT-I for cancer patients and their sleep-partner caregivers are fundamental and are applicable to each of the four intervention sessions. The intervention can be delivered by a Master’s level interventionist who has been trained in Psychology, Behavioral Medicine, or related field via HIPAA-compliant video platform to the patient and caregiver simultaneously.

The session content includes four modules: sleep behavior, sleep cognition, sleep in relationship, and relapse prevention, which is presented in Table 1. Session 1 introduces the intervention and focuses on providing psychoeducation about the two-process model of sleep, sleep hygiene, and stimulus control. Each partner’s current habits of sleep hygiene and stimulus control are reviewed, and goals for relevant behavioral changes are collaboratively discussed and negotiated.

Table 1.

MSOS Intervention Session Content

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| #1: Sleep Behavior | MSOS introduction |

| Review individuals’ sleep habits | |

| Psychoeducation on sleep behaviors: two process model of sleep, sleep hygiene, sleep control | |

| Setting goals for sleep behavior changes | |

| Homework assignment – sleep behaviors | |

| #2: Sleep Cognition | Review homework of session 1 |

| Psychoeducation on sleep cognition: identify noisy thoughts, active mind, automatic negative thoughts, worries, with focus on cancer-related cognition | |

| Setting goals for monitoring sleep cognition | |

| Homework assignment – sleep behaviors & monitoring sleep cognition | |

| #3: Sleep Cognition | Review homework of session 2 |

| Psychoeducation on sleep cognition: challenging and reframing noisy thoughts, active mind, automatic negative thoughts, worries, with focus on cancer-related cognition | |

| Setting goals for reframing sleep cognition | |

| Homework assignment – sleep behaviors & monitoring and reframing sleep cognition | |

| #4: Sleep in Relationship | Review homework of session 3 |

| -Psychoeducation on sleep in relationship: effective communication; behaviors, thoughts, and emotions in the cancer journey -Psychoeducation on good sleep maintenance and relapse prevention | |

| Setting goals for effective communication, good sleep maintenance and relapse prevention | |

| Homework assignment – sleep behaviors, monitoring and reframing sleep cognition, effective communication with partner, good sleep maintenance |

During Session 2, progress with behavior changes for sleep hygiene and stimulus control is reviewed and barriers adhering to behavior changes are addressed. Session 2 also focuses on providing psychoeducation on the connection between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, as well as identifying and discussing automatic thoughts that are cancer-related and sleep-specific that contribute to each partner’s sleep disturbance. In addition to practicing behavior changes for sleep hygiene and stimulus control, partners practice together monitoring their automatic thoughts that contribute to their sleep disturbance.

Session 3 focuses on providing psychoeducation on challenging unhelpful automatic thoughts, which involves identifying the unhelpful thinking style and reframing the automatic thought to produce a more balanced alternative thought. In addition to practicing behavior changes for sleep hygiene and stimulus control, and monitoring their maladaptive thoughts, partners practice together challenging their automatic thoughts that contribute to their sleep disturbance.

Session 4 focuses on discussing aspects of the close relationship and shared cancer experiences that also contribute to the couples’ sleep problems. Psychoeducation on effective communication, including self-disclosure, partner responsiveness, and relationship engagement is provided. Behaviors, thoughts, and emotions throughout the cancer journey, such as those related to fear of recurrence, cancer prognosis, caregiving stress, etc., are collaboratively discussed. Psychoeducation on maintaining changed healthy sleep habits and relapse prevention collaboratively is also discussed.

The sequence and duration of the MSOS intervention session contents can be tailored for individual dyads based on information obtained from the pre-intervention questionnaire and the daily sleep measures. For example, for a dyad whose member scores less than 13 on the 4-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale (ranges 0 to 21: ≤ 13 indicate distressed relationship; Sabourin et al., 2005), the topic of sleep in the relationship that is the content of session 4 can be discussed in the first session after the general introduction of the MSOS intervention. In other words, the psychoeducation on effective communication and general aspects of the close relationship and shared cancer experiences, which contribute to their sleep problems can be discussed in the first session and its progress can be monitored throughout the entirety of the MSOS intervention. The MSOS intervention protocol and measures are available (Kim et al., manuscript under review).

Intervention Satisfaction Survey.

After each intervention session, participants completed a total of eight brief questions on a 5-point Likert format (1: strongly disagree, 5: strongly agree), regarding the extent to which the intervention session was engaging, easy to understand, comprehensive, useful, relevant, motivated sleep behavior changes, motivated sleep cognition changes, and helped to prepare for making sleep-related changes.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics of the sample, means and standard deviations or percentages of study variables are reported in Table 2. The feasibility criteria were ≥ 75% of eligible dyads enrolled within the 4-month enrollment period, ≥ 80% of enrolled dyads completing the intervention (one week after the last intervention session and assessment), and no adverse events reported. The acceptability criteria were ≥ 80% of participants reporting satisfaction (≥ 4 on the 5-point rating scale) across all 8 intervention satisfaction survey questions. Differences in demographics and study variables between patients and caregivers at T1 and T2 were tested using paired t-tests. Changes in study variables from pre-intervention (T1) to post-intervention (T2) were also tested using paired t-tests and reported using Cohen’s d, which is a more informative effect size statistic than t-values for a pilot study with small sample. Statistical significance was set at a 2-tailed p-value < .05.

Table 2.

Sample Descriptives (n = 10 patient-caregiver dyads)

| T1 | T2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Caregivers | t or χ2 | Patients | Caregivers | t or χ2 | |

| Age | 64.53 (9.89) | 63.51 (12.42) | 0.88 | |||

| Gender (female) | 60% | 40% | 10.0** | |||

| Education | 21.33 | |||||

| High school/GED | 20% | 10% | ||||

| College | 50% | 80% | ||||

| Graduate degree | 30% | 10% | ||||

| Household Income | ||||||

| $0 – $70,000 | 0% | |||||

| $70,000 – $119,999 | 30% | |||||

| $120,000 – $$159,999 | 20% | |||||

| $160,000 – $209,999 | 20% | |||||

| > $300,000 | 10% | |||||

| Prefer not to answer | 20% | |||||

| Ethnicity | 4.53 | |||||

| Hispanic | 20% | 10% | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 80% | 90% | ||||

| Employment | 2.74 | |||||

| Paid full-time employed | 30% | 20% | ||||

| Paid part-time employed | 0% | 10% | ||||

| On leave with pay | 10% | 0% | ||||

| Retired | 50% | 60% | ||||

| Unemployed | 10% | 10% | ||||

| Cancer Type | Anus (1), Appendix (1), Colon (2), Esophagus (1), Jejunum (1), Liver (1), Pancreas (3) | |||||

| On treatment | 70% | - | 80% | - | ||

| Relationship duration | 28.04 (17.07) years | |||||

| Dysfunctional belief on sleep | ||||||

| Consequences | 4.08 (2.51) | 2.46 (1.64) | 2.08 (p=.067) | 3.92 (2.21) | 3.20 (1.48) | 0.74 |

| Worry | 4.67 (2.62) | 2.23 (2.29) | 2.83* | 3.58 (2.37) | 2.30 (2.31) | 1.93 (p=.086) |

| Expectation | 5.40 (3.26) | 6.05 (2.01) | −0.51 | 5.05 (2.60) | 5.85 (2.08) | −0.89 |

| Medications | 3.37 (2.38) | 1.93 (1.51) | 1.98 (p=.079) | 2.70 (2.10) | 2.10 (1.28) | 0.90 |

| Attachment security | 3.63 (0.55) | 3.77 (0.35) | −0.58 | - | - | |

| Attachment anxiety | 1.45 (0.62) | 1.38 (0.42) | 0.57 | - | - | |

| Attachment avoidance | 1.44 (0.69) | 1.30 (0.49) | 0.67 | - | - | |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Results

Sample Characteristics

As shown in Table 2, participants were primarily middle-aged, non-Hispanic White, and retired, and had some degree of college education and middle-class household income. Most patients were on treatment at both T1 and T2 for various types of GI cancer. On average, patients and caregivers had been in a relationship for over 28 years and reported mild to moderate levels of sleep disturbance and dysfunctional belief about sleep. Both patients and caregivers also reported on average high levels of attachment security and relationship satisfaction, and low levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance, on the measures we used. At T1, 40%, 10%, and 10% of patients had sub-threshold, moderate, and severe levels of insomnia, respectively; at T2, 70% had sub-threshold levels of insomnia, and none had moderate or severe levels of insomnia. Among caregivers, 50% at T1 and 60% at T2 had sub-threshold levels of insomnia, and none had moderate or severe levels of insomnia at either timepoint.

Enrollment Feasibility

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 241 patients with GI cancer were identified as potentially eligible for the study. We were able to contact 77.5% of patients who met the eligibility criteria by medical records. Of those, 30.3% refused to be screened. Among those who were screened, 81.6% were ineligible after screening: 45.2% were single, 24.2% reported PSQI < 5, 8.1% were divorced/separated, and 4.8% had a partner who was out of the country for the unforeseeable future. Of those eligible and screened, 92.9% (13 out of 14 dyads) enrolled during the 4-month enrollment period. Among 13 dyads enrolled, 3 dyads (23.1%) withdrew after the first intervention session due to cancer recurrence or becoming too busy, leaving 10 dyads who completed the intervention.

Intervention Fidelity

The fidelity to the intervention protocol was ensured by YK who reviewed 100% of the intervention sessions. Based on individuals’ sleep hygiene and stimulus control data obtained from daily sleep diary, DBAS total score, and attachment orientations and relationship satisfaction scores at T1, the behavior, cognition, and relationship modules, respectively, of the MSOS intervention sessions were tailored for each dyad. On average, session 1 took slightly over 1 hour (1 hour 16 minutes) but all other sessions took 1 hour (1 hour 4 minutes each for sessions 2 and 3; and 1 hour 2 minutes for session 4). No adverse events were reported.

Intervention Acceptability

Participants reported high satisfaction with the MSOS intervention in 8 domains, with an average of 4.76 on a 1 (not satisfied) to 5 (completely satisfied) scale, ranging 4.53 to 5.00 (Table 3). Levels of satisfaction remained consistently high throughout the intervention sessions (p > .34), except for two domains. First, the levels of agreement on the intervention motivating participants for making changes in sleep behaviors slightly decreased at the third session (means = 4.42, 4.67, 4.58, and 4.92 at sessions 1 through 4, respectively, F = 6.06, p = .032). Second, the levels of agreement on the intervention motivating participants for making changes in sleep cognitions gradually improved (means from 4.43 to 4.79 across the 4 sessions, F = 7.22, p = .19).

Table 3.

Intervention Satisfaction

| Patients | Caregivers | |

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Engaging | 4.88 (0.32) | 4.87 (0.32) |

| Easy to understand | 4.98 (0.07) | 5.00 (0.00) |

| Comprehensive | 4.86 (0.31) | 4.78 (0.38) |

| Useful | 4.80 (0.37) | 4.59 (0.44) |

| Relevant | 4.89 (0.29) | 4.83 (0.29) |

| Motivating sleep behavior changes | 4.54 (0.74) | 4.53 (0.50) |

| Motivating sleep cognition changes | 4.77 (0.32) | 4.63 (0.43) |

| Helpful prepared for making sleep-related changes | 4.48 (0.62) | 4.77 (0.43) |

| Average | 4.76 (0.29) | 4.75 (0.28) |

All participants (20 persons) agreed that the number of sessions (4), the interval (weekly), the delivery mode (Zoom as opposed to in-person or telephone), and the interaction mode with the interventionist (live as opposed to non-interactive or internet-based animated interaction) of the MSOS intervention were optimal. All participants preferred attending all sessions with their partners (as opposed to alone or with someone else). One participant (out of 20) suggested reducing the number of days requested for completing the daily sleep diary.

Preliminary Intervention Efficacy

Prior to receiving the MSOS intervention (T1), the most prevalent sleep hygiene behaviors for which participants did not meet the recommendation was lack of exercise (60% of patients and 30% of caregivers were inactive), which was followed by alcohol intake (40% of patients and 30% of caregivers) and caffeine intake (10% of patients and 20% of caregivers). The most prevalent problematic sleep stimulus control behavior was doing non-sleep activities in bed (70% of patients and 90% of caregivers) and having an inconsistent waking time (the range of waking time reported in the daily sleep diary across the 7 consecutive days was greater than 2 hours: 80% of patients and 50% of caregivers), which was followed by napping (40% of patients and 30% of caregivers).

As shown in Table 2, both patients and caregivers had moderate levels of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep and poor sleep efficiency (< 81%) that was assessed using the 7-day daily sleep diary at T1. Patients reported higher levels of total dysfunctional beliefs about sleep and worry than their caregivers, but both reported comparable levels of overall sleep disturbance, subjective sleep quality, sleep beliefs on consequences, expectations, and medications, as well as attachment orientations, relationship satisfaction, and sleep efficiency at T1.

After receiving the MSOS intervention (T2), the majority increased the duration of engaging in moderate exercise (50% of inactive patients and 66% of inactive caregivers at T1) and either reduced the amount or adjusted the time for last alcoholic beverage intake to be earlier in the evening (75% of patients who did not meet the recommendation and 66% of caregivers who did not meet the recommendation at T1). Also, the majority reduced the time in bed doing non-sleep activities (86% of patients and 89% of caregivers who did non-sleep activities in bed at T1), woke up within a more consistent time frame across days (63% of patients and 60% of caregivers who had various waking time at T1), and reduced the duration of naps (50% of patients and 100% of caregivers napped at T1). At T2, both patients and caregivers reported mild levels of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep and had good sleep efficiency (> 87%). Patients reported comparable levels of sleep patterns with their caregivers at T2.

As shown in Table 4, sleep efficiency, the primary outcome that was derived from the sleep diary, of both patients and caregivers, significantly improved after the MSOS intervention (Cohen’s d = 1.04 and 1.47 for patients and caregivers, respectively, t > 3.28, p < .01). Among secondary outcomes, caregivers’ subjective sleep quality also significantly improved (Cohen’s d= .78, t = 2.45, p= .037). Effect sizes of the MSOS intervention on reducing other indicators of sleep disturbance for patients and caregivers were small-to-medium.

Table 4.

Intervention Effects

| Patients | Caregivers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | d | T1 | T2 | d | |

| Sleep efficiency | 77.61 (15.48) | 87.04 (9.55) | −1.04** | 81.66 (8.02) | 90.92 (8.67) | −1.47*** |

| PSQI subjective sleep quality | 1.10 (0.99) | 0.90 (0.57) | 0.22 | 1.10 (0.57) | 0.70 (0.48) | 0.78* |

| Dysfunctional belief on sleep | 4.33 (1.94) | 3.71 (1.78) | 0.32 | 3.18 (1.45) | 2.96 (1.26) | 0.17 |

| DAS | 15.20 (3.94) | 15.30 (3.77) | −0.09 | 16.20 (3.55) | 15.60 (3.75) | 0.30 |

p < .085

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale

Discussion

The results of this pilot study support the feasibility and acceptability, as well as provide the preliminary efficacy of the newly developed sleep intervention, called MSOS, for both adult patients with GI cancer and their sleep-partner caregivers. Specifically, among adult patients with cancer who are not single, divorced, or separated, approximately half had at least mild-to-moderate sleep disturbance and a sleep-partner caregiver who also had mild-to moderate sleep disturbance, supporting the high prevalence of sleep disturbance in both adult patients with cancer and their caregivers. In addition, most of our participants were willing to make changes in even their sub-optimal, as opposed to severely disturbed, sleep habits. Furthermore, in a study of spousal caregivers of patients with dementia, the caregivers continued to have significant ongoing sleep problems after the death or institutionalization of their demented spouses (Gao et al., 2019). This result suggests, sleep disturbance, once developed, has lasting effects even after ceasing the caregiver role. Thus, a rather lenient intervention inclusion criterion for the levels of sleep disturbance particularly for vulnerable populations, such as adult patients with cancer and their sleep-partner caregivers, may be desirable to yield a broader impact.

Our results support high feasibility of providing a dyadic sleep intervention to patients who are mainly on treatment. Treatment status was not an inclusion or exclusion criterion for this pilot study. However, MSOS accommodates the symptoms and experience of cancer as well as potential treatment effects on the patients’ disturbed sleep. Thus, the MSOS intervention can be useful for those who manage current and lasting cancer-related symptoms, in which both the patients and their family caregivers are often collaboratively involved. However, the effects of MSOS intervention on treatment adherence, prognostic outcomes, healthcare utilization, and quality of life need to be tested in future studies.

The high acceptability is also achieved by high satisfaction with the intervention content, procedure, and measurement, and the interventionist. MSOS intervention delivers key components of CBT-I (sleep behavior change and addressing sleep-related cognition) in the context of close relationship for both patients and caregivers, whose sleep disturbances were equally addressed. Our results suggest that the MSOS intervention, which was delivered comprehensively and compactly in a minimum number of sessions, is highly feasible and acceptable. eHealth intervention delivered by a trained interventionist, which gained popularity and familiarity through the COVID-19 pandemic, was also considerably acceptable as it capitalizes on the human-side of the technology, as opposed to non-interactive or animated interactions. Furthermore, the finding that all participants preferred attending the intervention with their sleep-partner caregivers, as opposed to alone or with someone else, supports the exceptional acceptability of dyadic sleep intervention. However, a potential bias in sampling for couples who agreed to participate in a study together should also be noted. In addition, the efficacy and effectiveness of dyadic format, as opposed to that of individual or group, for reducing individuals’ sleep disturbance should also be tested in future studies.

Our results hint that the MSOS intervention is particularly effective in modifying sleep stimulus control behaviors that were the most prevalent problematic sleep behaviors among both patients with cancer and caregivers. Furthermore, a few studies with medical populations showed that medical characteristics of one member of a dyad affected the partner’s sleep. For example, osteoarthritis patients’ pain affected their spouse’s sleep (but not the other way around: Martire et al., 2013); poorer condition of dementia patients related to husband caregivers’ increased time awake after sleep onset (Mills et al., 2009); and caring for a patient with a more severe type of cancer related to chronic sleep disturbance of the caregivers (Fletcher, Dodd, Schumacher, & Miaskowski, 2008; Passik & Kirsh, 2005). None of these studies, however, has intervened on both sleep partners simultaneously. On the other hand, the large effects of the MSOS intervention on improving sleep efficiency of both patients and caregivers, as well as enhancing caregivers’ subjective sleep quality and reducing caregivers’ overall sleep disturbance, clearly illustrate that the efficacy of the MSOS intervention are promising. Our preliminary findings should be replicated with a larger sample for further adequate interpretation.

Our findings also suggest that intervening on both sleep partners who serve as each other’s comrade to make desirable changes, as opposed to targeting a sole member in the dyad, may be an optimal strategy that is highly likely to yield a larger impact on improving sleep and general health. In addition, existing studies have shown that the husband’s loneliness was related to his wife’s poor sleep (Segrin & Burke, 2015), and the wife’s perception of partner interactions during the day predicted her husband’s better sleep (Hasler & Troxel, 2010). Thus, investigating MSOS’s efficacy in improving mutual sleep regulatory patterns where partners influence the reduction of each other’s sleep disturbance is highly warranted. It will be particularly critical among at-risk dyads of adult patients with cancer and their sleep partners. Examining the potential role of close relationship factors (i.e., intimacy and self-disclosure) as the pathway of sleep intervention is also warranted.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, we employed a single arm study design as the first step of this feasibility study, which lacks a control or comparison group that would have provided a stronger conclusion regarding the efficacy of the MSOS intervention. Similarly, the current design, small sample size, and potentially biased sample prevented the ability to test the superiority of novelty involving patient-caregiver dyadic intervention, as opposed to a small, two-person stranger group format intervention. Second, our current enrollment criterion of having at least mild-to-moderate sleep disturbance (PSQI ≥ 5) may contribute to a floor effect. Third, the generalizability of the current findings to different types of cancer, time since diagnosis, treatment trajectory, and language proficiency as well as to patients without a consistent sleep partner and patients without at least mild sleep disturbance, which are not included in the current study, is limited. Fourth, testing gender, race and ethnicity, and other group differences as well as dyadic (e.g., relationship duration, relationship satisfaction) and individual (e.g., personality, coping strategies) differences in the intervention efficacy was not feasible. These limitations should be addressed in larger future studies with diverse participants.

In summary, although sleep disturbance is common in both patients with cancer and their family caregivers, no studies to date have investigated the efficacy of dyadic sleep interventions involving both patients with cancer and their caregivers simultaneously. Our findings of this pilot study suggest that testing the efficacy of MSOS, an innovative and timely intervention for couples/dyads who are facing cancer, in an RCT with a larger sample is warranted. The knowledge from this line of investigation may have substantial implications for traditional sleep research and practice with medical populations, shifting the emphasis from individual- to dyad/family-based approaches.

Highlights.

Psychobehavioral intervention for both adults with cancer and their sleep partners

Dyadic sleep intervention is feasible and acceptable

Novel insights for dyad/family-based approach for improving sleep health

Acknowledgement:

The authors extend their appreciation to all the families who participated in this investigation, and to Drs. Alberto Ramos and William Wohlgemuth for their inputs to earlier phase of the investigation. The first author dedicates this research to the memory of Heekyoung Kim.

Funding:

The writing of this manuscript was supported by National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR016838) and Sylvester’s Cancer Survivorship Research Pilot Program (PG012574) to YK.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have financial conflict of interest to disclose.

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Berger AM (2009, Jul). Update on the state of the science: Seep-wake disturbances an adult patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(4), 401–401. 10.1188/09.Onf.E165-E177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootzin RR, & Epstein DR (2011). Understanding and Treating Insomnia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 435–458. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989, May). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index - a New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/Doi 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG, Ernst JM, Gibbs AC, Stickgold R, & Hobson JA (2002, Jul). Do lonely days invade the nights? Potential social modulation of sleep efficiency. Psychological Science, 13(4), 384–387. https://doi.org/Doi 10.1111/1467-9280.00469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, & Miller MA (2010, May 1). Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Sleep, 33(5), 585–592. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney CE, Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Krystal AD, Lichstein KL, & Morin CM (2012, Feb 1). The Consensus Sleep Diary: Standardizing Prospective Sleep Self-Monitoring. Sleep, 35(2), 287–302. 10.5665/sleep.1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PA (2006, Mar-Apr). A brief behavioral sleep intervention for family caregivers of persons with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 29(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/Doi 10.1097/00002820-200603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS (1997, Aug). Adult attachment and personality: Converging evidence and a new measure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(8), 865–883. https://doi.org/Doi 10.1177/0146167297238007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, & Perach R (2012, Jul 1). Sleep Duration, Nap Habits, and Mortality in Older Persons. Sleep, 35(7), 1003–1009. 10.5665/sleep.1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhruva A, Lee K, Paul SM, West C, Dunn L, Dodd M, Aouizerat BE, Cooper B, Swift P, & Miaskowski C (2012, Jan-Feb). Sleep-Wake Circadian Activity Rhythms and Fatigue in Family Caregivers of Oncology Patients. Cancer Nursing, 35(1), 70–81. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182194a25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Jones DE, Hostetler ML, Roettger ME, Paul IM, & Ehrenthal DB (2016, Aug). Couple-Focused Prevention at the Transition to Parenthood, a Randomized Trial: Effects on Coparenting, Parenting, Family Violence, and Parent and Child Adjustment. Prevention Science, 17(6), 751–764. 10.1007/s11121-016-0674-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, Rundle AG, Zammit GK, & Malaspina D (2007, Dec 1). Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes incidence in a large US sample. Sleep, 30(12), 1667–1673. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao CL, Chapagain NY, & Scullin MK (2019, Aug). Sleep Duration and Sleep Quality in Caregivers of Patients With Dementia A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Jama Network Open, 2(8). https://doi.org/ARTN e19989110.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn HE, Buysse DJ, Matthews KA, Kline CE, Cribbet MR, & Troxel WM (2017, Jan 1). Sleep-Wake Concordance in Couples Is Inversely Associated With Cardiovascular Disease Risk Markers. Sleep, 40(1). 10.1093/sleep/zsw028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn HE, & Eberhardt KR (2019, Apr 13). Family Dynamics in Sleep Health and Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep, 21(5), 39. 10.1007/s11906-019-0944-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn HE, Lee S, Eberhardt KR, Buxton OM, & Troxel WM (2021, Apr). Nightly sleep-wake concordance and daily marital interactions. Sleep Health, 7(2), 266–272. 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe S, Berger K, & Investigators FS (2002, Sep). The association between caregiver burden and sleep disturbances in partners of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Age and Ageing, 31(5), 349–354. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1093/ageing/31.5.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B, Ross J, & Sanchez-Reilly S (2014, Sep-Oct). Sleeping in the arms of cancer: a review of sleeping disorders among patients with cancer. Cancer J, 20(5), 299–305. 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, & Troxel WM (2010, Oct). Couples’ Nighttime Sleep Efficiency and Concordance: Evidence for Bidirectional Associations With Daytime Relationship Functioning. Psychosomatic medicine, 72(8), 794–801. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ecd08a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin MR (2015). Why Sleep Is Important for Health: A Psychoneuroimmunology Perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol 66, 66, 143–172. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JA, Rash JA, Campbell TS, Savard J, Gehrman PR, Perlis M, Carlson LE, & Garland SN (2016, Jun). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) in cancer survivors. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 27, 20–28. 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane HS, Slatcher RB, Reynolds BM, Repetti RL, & Robles TF (2014, Aug). Daily Self-Disclosure and Sleep in Couples. Health Psychology, 33(8), 813–822. 10.1037/hea0000077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DA, & McHorney CA (2002, Mar). The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. Journal of Family Practice, 51(3), 229–235. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000174257000006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Ting A, Steel JL, Tsai TC (2022). Protocol of a dyadic sleep intervention for adult patients with cancer and their sleep-partner caregivers. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL (2010, Oct). Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 24(5), 731–743. 10.1016/j.beem.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochar J, Fredman L, Stone KL, Cauley JA, & Fractures SO (2007, Dec). Sleep problems in elderly women caregivers depend on the level of depressive symptoms: Results of the caregiver-study of osteoporotic fractures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(12), 2003–2009. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotronoulas G, Wengstrom Y, & Kearney N (2013, Jan-Feb). Sleep Patterns and Sleep-Impairing Factors of Persons Providing Informal Care for People With Cancer A Critical Review of the Literature. Cancer Nursing, 36(1), E1–E15. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182456c38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudlow PA, Cha DS, Lam RW, & McIntyre RS (2013, Oct). Sleep architecture variation: a mediator of metabolic disturbance in individuals with major depressive disorder. Sleep Medicine, 14(10), 943–949. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Cho M, Miaskowski C, & Dodd M (2004, Jun). Impaired sleep and rhythms in persons with cancer. Sleep Med Rev, 8(3), 199–212. 10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Mills PJ, Rissling M, Fiorentino L, Natarajan L, Dimsdale JE, Sadler GR, Parker BA, & Ancoli-Israel S (2012, Jul). Fatigue and sleep quality are associated with changes in inflammatory markers in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 26(5), 706–713. 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Hall DL, Ngo LH, Liu QQ, Bain PA, & Yeh GY (2021, Feb). Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 55. https://doi.org/ARTN 10137610.1016/j.smrv.2020.101376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Keefe FJ, Schulz R, Stephens MAP, & Mogle JA (2013, Sep). The impact of daily arthritis pain on spouse sleep. Pain, 154(9), 1725–1731. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medic G, Wille M, & Hemels ME (2017). Short-and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and science of sleep, 9, 151. 10.2147/NSS.S134864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor A, Hamill K, Jenkins MM, Baucom DH, Norton PJ, & Drummond SPA (2019, May 8). Partner-assisted cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia versus cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 20. https://doi.org/ARTN 26210.1186/s13063-019-3334-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, Ancoli-Israel S, von Kanel R, Mausbach BT, Aschbacher K, Patterson TL, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE, & Grant I (2009, Jul). Effects of gender and dementia severity on Alzheimer’s disease caregivers’ sleep and biomarkers of coagulation and inflammation. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 23(5), 605–610. 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk TH, Buysse DJ, Potts JM, DeGrazia JM, & Kupfer DJ (2004, May). Morningness-eveningness and lifestyle regularity [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Chronobiology International, 21(3), 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, & Ivers H (2011, Jun). The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric Indicators to Detect Insomnia Cases and Evaluate Treatment Response. Sleep, 34(5), 601–608. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Rodrigue S, & Ivers H (2003, Mar-Apr). Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosomatic medicine, 65(2), 259–267. 10.1097/01.Psy.0000030391.09558.A3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Vallieres A, & Ivers H (2007, Nov 1). Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): Validation of a brief version (DBAS-16). Sleep, 30(11), 1547–1554. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2011). National Institutes of Health Sleep Disorders Research Plan. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/2011-national-institutes-health-sleep-disorders.

- Pal PK, Thennarasu K, Fleming J, Schulzer M, Brown T, & Calne SM (2004, Mar). Nocturnal sleep disturbances and daytime dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s disease and in their caregivers. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 10(3), 157–168. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2003.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palesh O, Peppone L, Innominato PF, Janelsins M, Jeong M, Sprod L, Savard J, Rotatori M, Kesler S, Telli M, & Mustian K (2012, Dec 17). Prevalence, putative mechanisms, and current management of sleep problems during chemotherapy for cancer. Nat Sci Sleep, 4, 151–162. 10.2147/NSS.S18895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palesh O, Solomon N, Hofmeister E, Jo B, Shen H, Cassidy-Eagle E, Innominato PF, Mustian K, & Kesler S (2020, Oct 13). A novel approach to management of sleep-associated problems in patients with breast cancer (MOSAIC) during chemotherapy : A pilot study. Sleep, 43(10). 10.1093/sleep/zsaa070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AJK, Clerx WM, O’Brien CS, Sano A, Barger LK, Picard RW, Lockley SW, Klerman EB, & Czeisler CA (2017, Jun 12). Irregular sleep/wake patterns are associated with poorer academic performance and delayed circadian and sleep/wake timing. Sci Rep, 7(1), 3216. 10.1038/s41598-017-03171-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, & Treanor JJ (2005, May). Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychology, 24(3), 297–306. 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittman M, Hinojosa MS, & Findley K (2009, Feb). Subjective Sleep, Burden, Depression, and General Health Among Caregivers of Veterans Poststroke. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 41(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1097/JNN.0b013e318193459a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin S, Valois P, & Lussier Y (2005, Mar). Development and validation of a brief version of the Dyadic Adjustment SCale with a nonparametric item analysis model. Psychological Assessment, 17(1), 15–27. 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Mindell JA, & Owens J (2011, Oct). Why care about sleep of infants and their parents? Sleep Medicine Reviews, 15(5), 335–337. 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savard J, Ivers H, Savard MH, Morin CM, Caplette-Gingras A, Bouchard S, & Lacroix G (2021, Nov). Efficacy of a stepped care approach to deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in cancer patients: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Sleep, 44(11). https://doi.org/ARTN zsab16610.1093/sleep/zsab166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, & Burke TJ (2015, May 4). Loneliness and Sleep Quality: Dyadic Effects and Stress Effects. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 13(3), 241–254. 10.1080/15402002.2013.860897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira AP, Friedman L, Beaudreau SA, Ancoli-Israel S, Hernandez B, Sheikh J, & Yesavage J (2010, Mar). Sleep and physical functioning in family caregivers of older adults with memory impairment. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(2), 306–311. 10.1017/S1041610209991153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RG, Brainard GC, Blask DE, Lockley SW, & Motta ME (2014, May-Jun). Breast Cancer and Circadian Disruption From Electric Lighting in the Modern World. Ca-a Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 64(3), 207–218. 10.3322/caac.21218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel WM (2010). It’s More than Sex: Exploring the Dyadic Nature of Sleep and Implications for Health. Psychosomatic medicine, 72(6), 578. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181de7ff8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel WM, Robles TF, Hall M, & Buysse DJ (2007, Oct). Marital quality and the marital bed: examining the covariation between relationship quality and sleep. Sleep Med Rev, 11(5), 389–404. 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters EM, Phillips AJK, Boardman JM, Norton PJ, & Drummond SPA (2020, Aug). Vulnerability and resistance to sleep disruption by a partner: A study of bed-sharing couples. Sleep Health, 6(4), 506–512. 10.1016/j.sleh.2019.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters EM, Phillips AJK, Mellor A, Hamill K, Jenkins MM, Norton PJ, Baucom DH, & Drummond SPA (2020, Jan). Sleep and wake are shared and transmitted between individuals with insomnia and their bed-sharing partners. Sleep, 43(1). https://doi.org/ARTN zsz20610.1093/sleep/zsz206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Kikuchi H, Tanaka K, & Takahashi M (2010, Feb 1). Association of Short Sleep Duration with Weight Gain and Obesity at 1-Year Follow-Up: A Large-Scale Prospective Study. Sleep, 33(2), 161–167. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1093/sleep/33.2.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ES, Michaud AL, & Recklitis CJ (2020, Jan 1). Developing efficient and effective behavioral treatment for insomnia in cancer survivors: Results of a stepped care trial. Cancer, 126(1), 165–173. 10.1002/cncr.32509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.