Abstract

Introduction:

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are managed syndromically in most developing countries. In Zimbabwe, men presenting with urethral discharge are treated with a single intramuscular dose of kanamycin or ceftriaxone in combination with a week’s course of oral doxycycline. This study was designed to assess the current etiology of urethral discharge and other STIs to inform current syndromic management regimens.

Methods:

We conducted a study among 200 men with urethral discharge presenting at 6 regionally diverse STI clinics in Zimbabwe. Urethral specimens were tested by multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Trichomonas vaginalis. In addition, serologic testing for syphilis and HIV was performed.

Results:

Among the 200 studied men, one or more pathogens were identified in 163 (81.5%) men, including N. gonorrhoeae in 147 (73.5%), C. trachomatis in 45 (22.5%), T. vaginalis in 8 (4.0%), and M. genitalium in 7 (3.5%). Among all men, 121 (60%) had a single infection, 40 (20%) had dual infections, and 2 (1%) had 3 infections. Among the 45 men with C. trachomatis, 36 (80%) were coinfected with N. gonorrhoeae. Overall, 156 (78%) men had either N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis identified. Of 151 men who consented to HIV testing, 43 (28.5%) tested positive. There were no differences in HIV status by study site or by urethral pathogen detected.

Conclusions:

Among men presenting at Zimbabwe STI clinics with urethral discharge, N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are the most commonly associated pathogens. Current syndromic management guidelines seem to be adequate for the treatment for symptomatic men, but future guidelines must be informed by ongoing monitoring of gonococcal resistance.

Urethritis in sexually active men, usually presenting with urethral discharge with or without concomitant dysuria, is almost always caused by sexually transmitted pathogens, most commonly Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.1 Treatment of this condition alleviates symptoms and prevents complications in men and also serves an important public health goal in preventing ongoing transmission of pathogens that are an important cause of infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and other chronic reproductive tract diseases among women and may facilitate the transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1,2 In the absence of diagnostic tools to differentiate between causative agents, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including urethral discharge in men, are treated and reported syndromically in most developing countries.3

A total of 56,540 cases of male urethral discharge were reported to the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care in 2015, comprising 22.4% of all reported STI cases in the country (unpublished). The 2012 Zimbabwe STI Treatment Guidelines advise treatment of urethral discharge in men with a combination of antimicrobials active against both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis, currently kanamycin (400 mg intramuscularly) or ceftriaxone (250 mg intramuscularly), plus either doxycycline (100 mg twice a day orally for 7 days) or a single oral dose of azithromycin (1.0 g).4 In addition to treating both gonorrhea and chlamydial infection, this combination treatment is designed to provide a 2-drug regimen to treat gonorrhea, a strategy that might reduce selection of increasingly resistant strains of N. gonorrhoeae.5 However, the success of syndromic management of urethral discharge and other STI syndromes hinges on assumptions of underlying causation and the antimicrobial susceptibility of the causative pathogens. In addition to rapidly evolving resistance in N. gonorrhoeae, shifts in the epidemiology of etiologic agents may render the strategy useless. For example, in industrialized countries, Mycoplasma genitalium has emerged as a significant cause of male urethritis,6,7 a pathogen less reliably susceptible to doxycycline and azithromycin.8

Accordingly, where syndromic management is used, the etiologies of STI syndromes and the susceptibility of selected pathogens should periodically be reassessed to inform potential modifications in recommended treatments. We designed and implemented the Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study to evaluate current syndromic management in Zimbabwe and, in this article, present the results in men with urethral discharge.

METHODS

The Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study was conducted in 2014 to 2015. A detailed description of the study methodology has been presented elsewhere,9 and the full study protocol and questionnaires are available online.10 In brief, we enrolled 600 patients presenting with STI-related syndromes (urethral discharge in men, vaginal discharge in women, and genital ulcer disease in men and women) at 6 geographically diverse STI clinics in Zimbabwe: Mbare and Budiriro clinics in Harare, the country capital; Khami Road and Nkulumane clinics in Bulawayo, the country’s seconds largest city; Dulibadzimu clinic in Beitbridge, a busy town on the border with South Africa; and rural Gutu Road Hospital clinic in Masvingo Province. The results of the vaginal discharge and genital ulcer disease components of the study will be published elsewhere. This article reports on the 200 men who presented with urethral discharge with or without dysuria.

A trained team of 3 study nurses enrolled patients during sequential 3- to 4-month periods at each of the study sites.

For purposes of the analysis in this article, clinics were combined into 3 regions: Harare, Bulawayo, and Beitbridge/Gutu.

Consecutive male patients presenting with urethral discharge who consented to the study completed a paper-based, staff-administered questionnaire;10 underwent a standardized genital examination; and had a discharge sample taken by swab for Gram stain and a urine sample for etiologic testing. A blood sample was taken by venipuncture for HIV testing, for which separate consent was obtained. Questionnaire data were entered into an online database on the day of the study visit using hand-held devices. All paper questionnaires and specimens were shipped overnight to the research laboratory in Harare, where specimens were held at −70°C until shipped to the reference laboratory detailed hereinafter.

At the Harare laboratory, slides were Gram stained and examined under high-power magnification for the presence of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) and gram-negative intracellular diplococci (GNID). At the study laboratory, HIV testing was performed using the standard rapid testing algorithm used in Zimbabwe*. Urine specimens were sent to the STI Reference Laboratory at the National Institutes of Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg, South Africa, for the detection of N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, M. genitalium, and Trichomonas vaginalis by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) as described elsewhere.11

Gonococcal resistance testing was not performed as part of this study because resistance testing is ongoing in Zimbabwe as part of other projects.12 Furthermore, transporting “live” specimens to a reference laboratory without compromising viability would have added considerable expenses to an already tight budget.

Questionnaire and laboratory data were combined and analyzed using SAS software (Cary, NC). Statistical analyses included χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical data and Student t test for continuous variables.

Because we assumed the possibility of variations and clustering by clinic, we did not attempt to assess generalizability of the relative presence of pathogens associated with male urethral discharge in our study and hence did not calculate 95% confidence intervals. Rather, we present variation by region.

Institutional Review

The protocol, including consent forms and questionnaires, was reviewed and approved by the University of Zimbabwe (Joint Research and Ethics Committee of Parirenyatwa Central Hospital), the Zimbabwe Medical Research Council, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

RESULTS

Demographics and Risk Factors

Selected demographic characteristics and risk factors are presented in Table 1. With the exception of the low enrollment at Gutu Road Hospital (3 men), recruitment was fairly even by region, with 71 men recruited in Harare, 68 men recruited in Bulawayo, and 58 men recruited in Beitbridge. The low enrollment at the Gutu site was the result of low STI patient volume and a pragmatic decision to focus limited resources on sites where patient volume was higher and recruitment more productive. Nonetheless, we did not see any reason to exclude these men from our analyses, and they were included with the Beitbridge sample.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Behavioral Variables Among Male Patients Presenting With Urethral Discharge in Zimbabwe

| Clinical Sites (by Region) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harare | Bulawayo | Beitbridge/Gutu | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | Total | % | P | |

| Total | 71 | 35.5 | 68 | 34.0 | 61 | 30.5 | 200 | ||

| Ethnicity | NS | ||||||||

| Shona | 34 | 47.9 | 31 | 45.6 | 35 | 57.4 | 100 | 50.0 | |

| Ndebele | 27 | 38.0 | 24 | 35.3 | 14 | 22.9 | 65 | 32.5 | |

| Other | 10 | 14.1 | 13 | 19.1 | 12 | 19.7 | 35 | 17.5 | |

| Age, y | NS | ||||||||

| Mean | 30 | 28.6 | 29.2 | 29.4 | |||||

| Median | 28 | 29 | 29 | 29 | |||||

| Age category, y | NS | ||||||||

| 18–19 | 2 | 2.8 | 3 | 4.4 | 1 | 1.6 | 6 | 3.0 | |

| 20–24 | 14 | 19.7 | 20 | 29.4 | 17 | 27.9 | 51 | 25.5 | |

| 25–29 | 23 | 32.4 | 17 | 25.0 | 19 | 31.2 | 59 | 29.5 | |

| 30–34 | 15 | 21.1 | 18 | 26.5 | 12 | 19.7 | 45 | 22.5 | |

| 35–39 | 9 | 12.7 | 6 | 8.8 | 5 | 8.2 | 20 | 10.0 | |

| 40–44 | 3 | 4.3 | 3 | 4.4 | 6 | 9.8 | 12 | 6.0 | |

| ≥45 | 5 | 7.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.6 | 7 | 3.5 | |

| Marital status | NS | ||||||||

| Married | 27 | 38.0 | 24 | 35.3 | 14 | 23.0 | 65 | 32.5 | |

| Unmarried | 44 | 62.0 | 44 | 64.7 | 47 | 77.0 | 135 | 67.5 | |

| Employment | NS | ||||||||

| Employed | 36 | 49.3 | 34 | 50.0 | 25 | 41.0 | 95 | 47.5 | |

| Unemployed | 35 | 50.7 | 34 | 50.0 | 36 | 59.0 | 105 | 52.5 | |

| No. partners in the previous 3 mo | NS | ||||||||

| Mean | 1 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.6 | |||||

| Median | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Range | 0–3 | 0–5 | 1–9 | 0–9 | |||||

| >1 partner in the previous 3 mo | <0.01 | ||||||||

| No | 49 | 69.0 | 31 | 45.6 | 35 | 57.4 | 88 | 44.0 | |

| Yes | 22 | 31.0 | 37 | 54.4 | 26 | 42.6 | 112 | 56.0 | |

| Commercial sex in the previous 3 mo | NS | ||||||||

| No | 56 | 78.9 | 53 | 77.9 | 54 | 88.5 | 163 | 81.5 | |

| Yes | 15 | 21.1 | 15 | 22.1 | 7 | 11.5 | 37 | 18.5 | |

| Condom use in at last sex main partner* | NS | ||||||||

| No | 57 | 80.3 | 54 | 84.4 | 55 | 90.2 | 166 | 84.7 | |

| Yes | 14 | 19.7 | 10 | 15.6 | 6 | 9.8 | 30 | 15.3 | |

| Not applicable | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Condom use at last sex casual partner* | NS | ||||||||

| No | 38 | 64.4 | 33 | 49.3 | 30 | 49.2 | 101 | 54.0 | |

| Yes | 21 | 35.6 | 34 | 50.7 | 31 | 50.8 | 86 | 46.0 | |

| Not applicable | 12 | 1 | 13 | ||||||

| Perceived HIV status | NS | ||||||||

| Negative | 25 | 35.2 | 22 | 32.4 | 30 | 49.2 | 77 | 38.5 | |

| Positive | 13 | 18.3 | 13 | 19.1 | 7 | 11.5 | 33 | 16.5 | |

| Unknown | 33 | 46.5 | 33 | 48.5 | 24 | 39.3 | 90 | 45.0 | |

| STI history* | NS | ||||||||

| No | 42 | 64.6 | 41 | 60.3 | 39 | 63.9 | 122 | 62.9 | |

| Yes | 23 | 35.4 | 27 | 39.7 | 22 | 36.1 | 72 | 37.1 | |

| Missing | 6 | 6 | |||||||

Percentages and χ2 analysis limited to nonmissing data.

NS indicates not significant; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

There were no statistically significant differences by race and ethnicity by recruitment site, although the population in the Bulawayo area is predominantly Ndebele compared with the predominantly Shona population in Harare. The mean and median ages of the study group were 29.4 and 29 years, respectively; there were no differences by age and study region.

In terms of risk factors, men recruited at the Harare clinics were significantly less likely to report more than 1 sex partner in the previous 3 months compared with men recruited in the other regions (P < 0.01; data not shown), but no significant differences were noted for other risk factors. Overall, 44% of men had multiple sex partners, but only 18.5% reported having had sex with a sex worker in the previous 3 months. Of men in the study, 85% and 54% reported not using a condom at last sex with main and nonmain partners, respectively (Table 1).

Characterization of Urethral Discharge

On physical examination, the quantity of urethral discharge was described by the study clinician as “large” for 47% of men, “moderate” for 28% of men, and “small” for 25%. In addition, 57% of men presented with discharge characterized as “purulent,” 29% as “cloudy,” and 14% as “clear.” There was a strong association between quantity and character of the discharge, with larger amounts of discharge significantly more frequently described as “cloudy” or “purulent” and smaller amounts more frequently described as “clear” (P < 0.0001; data not shown).

Gram Stain Results

Gram stain results were available for all 200 men. Of these, 137 (68%) had stains showing GNID, indicative of gonococcal infection. Twelve men (6%) had at least 10 PMNs per high-power field (PMN/HPF) but no GNID, 16 men (8%) had 1 to 9 PMN/HPF and no GNID, and 35 men (17.5%) had a negative Gram stain. Compared with M-PCR as gold standard (see below), Gram stain (visualization of GNID) had the following performance statistics for the detection of N. gonorrhoeae: sensitivity, 93.2% (137/ 147); specificity, 100% (53/53); positive predictive value, 100% (147/147); and negative predictive value, 84.1% (53/63).

M-PCR Results

Results from the M-PCR were available for all 200 men. Of these, 147 (73.5%) men tested positive for N. gonorrhoeae, 45 men (22.5%) for C. trachomatis, 8 men (4%) for T. vaginalis, and 7 men (3.5%) for M. genitalium. At least 1 pathogen was identified in 163 (81.5%) men; 121 (60.5%) had single infections, 40 (20%) had dual infections, and 2 (1%) had 3 infections. Overall, either N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis was identified in 156 (78%) men. Of the 15 men with T. vaginalis (n = 8) or M. genitalium (n = 7) infections, respectively, 2 (25%) and 4 (57%) were single infections.

Most dual infections were a combination of gonorrhea and chlamydia found in 36 men. Thus, coinfection with chlamydia occurred among 36 (24.5%) of 147 men with gonorrhea, and coinfection with gonorrhea occurred among 36 (80%) of 45 men with chlamydia.

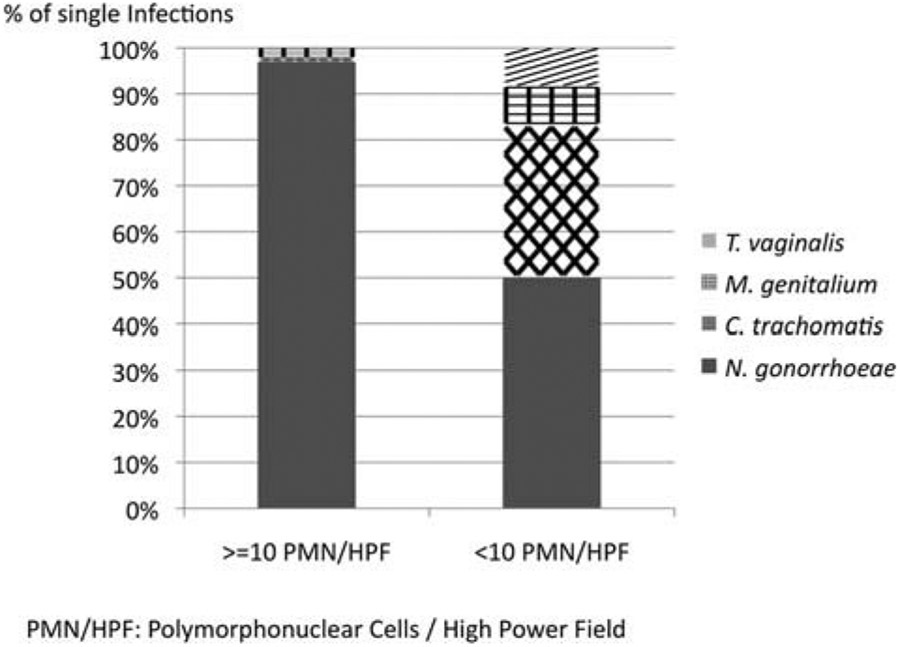

Of note, only 1 (2.8%) of 36 men with both chlamydia and gonorrhea had a Gram stain result of less than 10 PMN/HPF compared with 8 (88.9%) of 9 men with chlamydia who did not have a concomitant gonococcal infection (P < 0.0001). Moreover, among men with single infections (n = 121), men with Gram stain results of less than 10 PMN/HPF (n = 24) had a significantly higher positivity rate of C. trachomatis, T. vaginalis, or M. genitalium compared with men with Gram stain results of at least 10 PMN/HPF (P < 0.001; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Etiology of male urethral discharge in relation to Gram stain result.

Among 37 men with no infections detected, 24 (64.9%) had a negative Gram stain compared with only 11 (6.7%) among 163 men with any infection (P < 0.001; data not shown).

There was a significant relationship between clinician discharge assessment and the positivity rate of N. gonorrhoeae. Among men with discharge characterized as “large” and “purulent” (n = 93), 98% had gonorrhea compared with only 9% of men (n = 23) whose discharge was characterized as “small” and “clear” (P < 0.0001; data not shown).

Significant variations in etiologic patterns were noted between clinics (Table 2). However, when the analysis was limited to men with any infection detected, there was no longer a statistically significant difference in the positivity rate of N. gonorrhoeae across regions, but the positivity rate of C. trachomatis was higher in the Bulawayo clinics (40.7%) compared with the Harare and Beitbridge/Gutu clinics, respectively (17.6% and 24.1%, P < 0.01; data not shown). We did not find any statistically significant differences in etiologic patterns by age or ethnicity.

TABLE 2.

Regional Variation in the Etiology of Urethral Discharge in Men

| Pathogen | Clinical Sites (by Region) | Total (n = 200) | % | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harare (n = 71) | Bulawayo (n = 68) | Beitbridge/Gutu (n = 61) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| N. gonorrhoeae | 44 | 62.0 | 50 | 73.5 | 53 | 86.9 | 147 | 73.5 | <0.01* |

| C. trachomatis | 9 | 12.7 | 22 | 32.3 | 14 | 22.9 | 45 | 22.5 | <0.05 |

| M. genitalium | 2 | 2.8 | 3 | 4.4 | 2 | 3.3 | 7 | 3.5 | NS |

| T. vaginalis | 3 | 4.2 | 3 | 4.4 | 2 | 3.3 | 8 | 4.0 | NS |

| None | 20 | 28.2 | 14 | 20.6 | 3 | 4.9 | 37 | 18.5 | <0.001 |

No statistical differences when analyses were limited to men with any infection detected.

NS indicates not significant.

Treatment

Treatment as recommended by the Zimbabwe STI Treatment Guidelines for male urethral discharge syndrome was documented for 198 (99%) of 200 men.

HIV

Of 151 men who consented to HIV testing, 43 (28.5%) tested positive. Among these, 20 were known to be HIV infected at enrollment. The remaining patients were contacted by the study team (V.K.) and given their results.

There were no differences in HIV status by study site or by urethral pathogen detected.

DISCUSSION

In our study of men with urethral discharge presenting at a geographically diverse group of STI clinics in Zimbabwe, most (73.5%) had gonorrhea as evidenced by nucleic acid amplification testing. This is slightly lower than the 82.8% gonorrhea positivity rate among 130 men with urethral discharge enrolled in an N. gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility study conducted in 2010 to 2011 in Harare.12 However, the positivity rate of C. trachomatis in our study (22.5%) was higher than that in the earlier study (11.7%), and the number of N. gonorrhoeae/C. trachomatis dual infections was also higher. Infections with M. genitalium and T. vaginalis were low in both studies. The results of our study can be compared with a study conducted in 2006/2007 in Cape Town and Johannesburg showing gonorrhea rates among men with urethral discharge of 85.2% and 71.0% and chlamydia rates of 13.4% and 24.4% in the 2 cities, respectively.11

The analysis of our etiologic findings by Gram stain results sheds some light on these discrepancies and identifies a potentially important caveat when interpreting these results. As demonstrated in Figure 1, the relative positivity rate of C. trachomatis, M. genitalium, and T. vaginalis compared with N. gonorrhoeae was significantly higher among men with Gram-stained smears showing less than 10 PMN/HPF. In other words, men with urethral gonorrhea seem to have a much more vigorous inflammatory response than men infected with other pathogens, as has been demonstrated in other studies.13 The extent to which men with more pronounced symptoms (copious discharge, severe dysuria) are more likely to present to clinics than men with minimal symptoms, especially in potentially stigmatizing places with long wait times, may bias the study toward finding higher proportions of pathogens associated with symptomatic infections, that is, gonorrhea. Indeed, in our study, only 23 men (11.5%) presented with a small amount of clear discharge, and in this group, the positivity rate of gonorrhea was only 9% compared with 98% among men with purulent discharge.

A similar bias may have been operative in some studies of N. gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility, in which clinicians were instructed to obtain samples from more overtly symptomatic men (i.e., those with purulent discharge) to increase the likelihood of finding gonorrhea.12 Thus, complementary studies among (high-risk) asymptomatic men are necessary to more fully describe the epidemiology of pathogens associated with urethritis in men and the extent to which these infections can be transmitted and cause complications in women.

The (self-) selection for men with more symptomatic infections could have also played a role in finding a relatively limited number of M. genitalium or T. vaginalis infections in our study. Alternatively, the low rates of these infections could mirror lower overall prevalence in our study population compared with findings from studies conducted in the United States and other countries. Regardless of the explanation, our results are in line with other studies conducted in Zimbabwe and the Southern African region.11,12 As suggested previously, studies in (high-risk) asymptomatic populations should be conducted to better define the prevalence of urethral pathogens that elicit a less vigorous inflammatory response than N. gonorrhoeae.

A second limitation of our study relates to the pragmatic nature of clinic selection, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results. As previously explained, our study lacked the time and resources to randomly select clinics and study subjects. However, we purposively selected clinics to reflect geographic and ethnic differences. Indeed, these efforts resulted in some differences in behavioral characteristics between clinic populations. Moreover, etiologic results also varied, with some clinics having significantly higher proportions of men with no pathogens identified. Other pathogens associated with urethritis in men, such as Ureaplasma urealyticum and viral infections, including herpes simplex and adenoviruses, were not assessed in this study and could explain the absence of pathogens identified and the difference between clinics. Still, the relative presence of the different pathogens among men with any infection identified did not vary, with the exception of a higher C. trachomatis prevalence in the Bulawayo clinics. Even at the clinics with fewest pathogens identified, still more than 50% of the men presenting with urethral discharge had gonorrhea and more than 15% had chlamydia. Therefore, these results do not suggest that treatment protocols should differ regionally in Zimbabwe.

Among men consenting to HIV testing in our study, 28.5% tested positive, but no associations between HIV infection and the presence of urethral pathogens were found. A more detailed analysis of HIV infection among study participants falls outside the scope of this article but will be presented elsewhere.14

Because of limitations in our study methods that did not include collection of culture specimens, we did not assess N. gonorrhoeae antimicrobial resistance patterns. A recently published study from Zimbabwe showed high levels of gonococcal susceptibility to kanamycin and ceftriaxone,12 and antimicrobial resistance studies are ongoing. Thus, given the high presence of gonorrhea and chlamydia in our study population, current syndromic treatment guidelines comprising either kanamycin or ceftriaxone in combination with doxycycline or azithromycin seem to be appropriate for men presenting with urethral discharge in Zimbabwe clinics. However, because gonococcal and especially chlamydial infections are often asymptomatic, relying on the syndromic management of symptomatic patients is an inadequate strategy for the control and prevention of these infections in the general population. Advances in the development of highly sensitive and specific testing technologies are increasingly yielding inexpensive, easy to use, rapid point-of-care assays for common STI pathogens that will ultimately allow for etiologic testing of high-risk populations in resource-restricted countries, with a potentially much greater impact on STI control. In the meantime, etiologic surveys continue to play an important role in informing STI management guidelines and should be considered as integral to the syndromic approach and part of routine public health STI surveillance activities.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the following from the ZiCHIRe Study Team: Luanne Rodgers, Laboratory Scientist; Mebbina Muswera, State Registered Nurse (SRN) and State Registered Midwife (SRM); Sarah Vundhla, SRN, SRM; and Shirley Tshimanga, SRN, SRM. This study could not have been conducted without the gracious support and collaboration of the staff and patients of the following clinics: Mbare and Budiriro clinics in Harare, Nkulumane and Khami Road clinics in Bulawayo, Dulibadzimu clinic in Beitbridge, and Gutu Rural Hospital in Gutu.

The Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study was supported by funds from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through a cooperative agreement between the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the University of Zimbabwe Department of Community Medicine SEAM Project under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number IU2GGH000315-01.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

HIV testing in Zimbabwe follows a standard algorithm of the following HIV rapid tests: (1) initial test by First Response HIV 1–2.O [PremierMedical Corporation, Daman, India], (2) confirmatory test by Alere Determine HIV 1/2 [Alere, Waltham, MS] if the initial test result is positive, and (3) INSTI HIV1/HIV2 [Biolytical, Richmond, BC, Canada] as a tiebreaker if the initial and confirmatory tests are discrepant.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections: 2006–2015 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/9789241563475/en/.

- 2.Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 19:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections 2003. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42782/1/9241546263_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health and Child Care - AIDS and TB Unit. Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Reproductive Tract Infections in Zimbabwe. Harare, Zimbabwe. Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Rcomm Rep 2015; 64(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: From chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24:498–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mena L, Wang X, Mroczkowski TF, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium infections in asymptomatic men and men with urethritis attending a sexually transmitted diseases clinic in New Orleans. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:1167–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manhart LE, Jensen JS, Bradshaw CS, et al. Efficacy of antimicrobial therapy for Mycoplasma genitalium infections. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(Suppl 8):S802–S817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rietmeijer C, Mungati M, Machiha A, et al. The Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study: Design, methods, study population. STD Prevention Online 2017. Available at: http://www.stdpreventiononline.org/index.php/resources/detail/2114. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Zimbabwe STI Aetiology Study Group. The aetiology of sexually transmitted infections in Zimbabwe—Study protocol. STD Prevention Online 2014. Available at: http://www.stdpreventiononline.org/index.php/resources/detail/2039. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mhlongo S, Magooa P, Müller EE, et al. Etiology and STI/HIV coinfections among patients with urethral and vaginal discharge syndromes in South Africa. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37:566–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takuva S, Mugurungi O, Mutsvangwa J, et al. Etiology and antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens responsible for urethral discharge among men in Harare, Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Dis 2014; 41:713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rietmeijer CA, Mettenbrink CJ. Recalibrating the Gram stain diagnosis of male urethritis in the era of nucleic acid amplification testing. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39:18–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilmarx P, Gonese E, Lewis D, et al. HIV infection in patients with sexually transmitted infections in Zimbabwe—Results from the Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study. PLOS One 2017; Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]