Abstract

Introduction

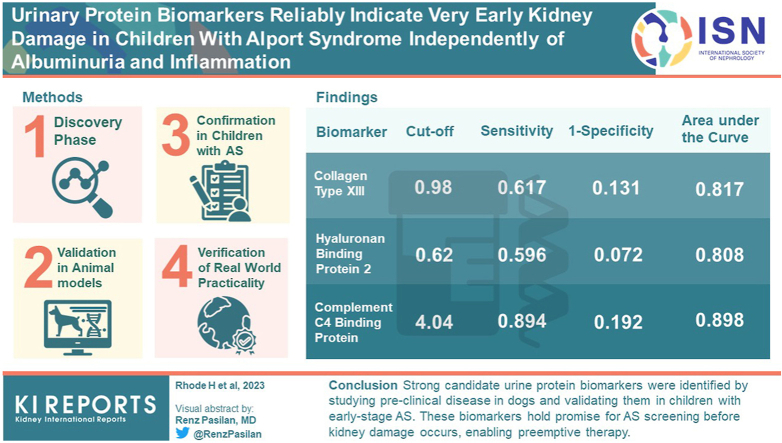

Alport syndrome (AS) is a hereditary type IV collagen disease. It starts shortly after birth, without clinical symptoms, and progresses to end-stage kidney disease early in life. The earlier therapy starts, the more effectively end-stage kidney disease can be delayed. Clearly then, to ensure preemptive therapy, early diagnosis is an essential prerequisite.

Methods

To provide early diagnosis, we searched for protein biomarkers (BMs) by mass spectrometry in dogs with AS stage 0. At this very early stage, we identified 74 candidate BMs. Of these, using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), we evaluated 27 in dogs and 28 in children, 50 with AS and 104 healthy controls.

Results

Most BMs from blood appeared as fractions of multiple variants of the same protein, as shown by their chromatographic distribution before mass spectrometry. Blood samples showed only minor differences because ELISAs rarely detect disease-specific variants. However, in urine , several proteins, individually or in combination, were promising indicators of very early and preclinical kidney injury. The BMs with the highest sensitivity and specificity were collagen type XIII, hyaluronan binding protein 2 (HABP2), and complement C4 binding protein (C4BP).

Conclusion

We generated very strong candidate BMs by our approach of first examining preclinical AS in dogs and then validating these BMs in children at early stages of disease. These BMs might serve for screening purposes for AS before the onset of kidney damage and therefore allow preemptive therapy.

Keywords: C4 binding protein, collagen type XIII, dogs, early screening, hyaluronan binding protein 2, proteomics

Graphical abstract

AS is a hereditary type IV collagen disease and is the most common monogenetic cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD). In its classical form, AS leads to end-stage kidney disease early in life. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme-inhibitors are able to delay disease progression if nephroprotective therapy is initiated preemptively. Therefore, it is unfortunate that early diagnosis of AS1 is rare and only available where the diagnosis has already been made in relatives. This is because there are no preclinical or screening diagnostic parameters before the onset of proteinuria despite nonspecific microhematuria. Therefore, there is no practicable BM yet in use for the preclinical detection of AS despite several early cellular alterations recently being claimed as potential “early” BMs.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Histopathological changes occur only late in disease progression. Genetic testing is recommended in symptomatic children.8 However, many children with AS are diagnosed too late to benefit very much from preemptive therapy.

AS develops only slowly in early childhood because of the maturation of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). This delay opens a “window of opportunity” for early diagnosis and therapy. Thus, there is an urgent need for preclinical BMs to act as GBM alarm signals before proteinuria. The earlier angiotensin-converting-enzyme-inhibition starts in an affected child, the better the chances are of improving life quality and life expectancy.9, 10, 11

Early diagnosis is therefore very important and was the ultimate target of our research into early BMs. However, finding BMs is also important for monitoring responses to therapy and for finding new therapeutic strategies.

Therefore, because early diagnosis is so important, we restricted our search for BMs to early stages of AS: stage 0 (isolated microhematuria) and stage I (microalbuminuria).12 We defined stage 0 as “preclinical,” because, despite microhematuria, there is no other specific sign of ongoing kidney disease. Searching for preclinical BMs is very challenging and not possible in toddlers. In addition, different time courses must be considered.

Our investigation spanned 10 years. It fell naturally into 4 parts, each building on the other as follows:

-

1.

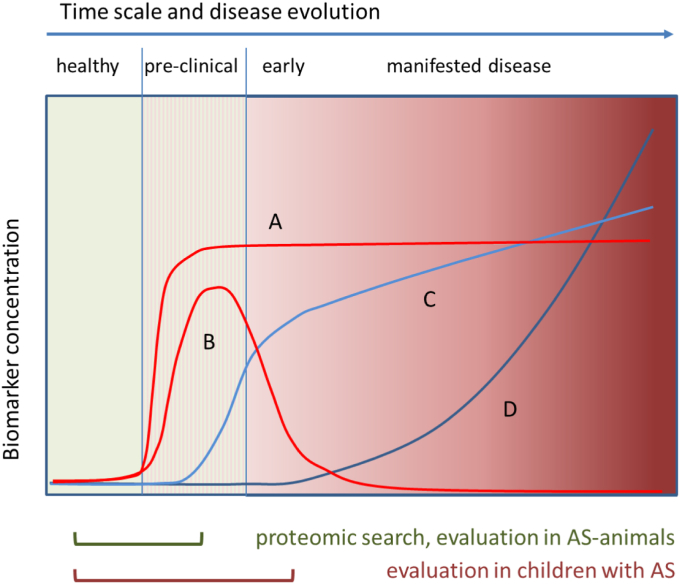

Screening in animal models: Our discovery phase started in animal models of AS with the goal of uncovering BMs of type A and B for glomerular injury (Figure 1). Mice and dogs with AS are ideal subjects for such an investigation because, given that type IV collagens are highly conserved, AS develops in all mammals.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Our search started in preclinical mice,13 and was improved by data from dogs.

-

2.

Validation in animal models: We validated some BMs in AS animals at preclinical stages of disease thereby demonstrating the reliability of the proteomic search principle.

-

3.

Confirmation in children with AS: In order to see whether our BM candidates occurred in humans, we tested samples from children. These children were in the early stages of AS and were part of the EARLY PRO-TECT Alport trial.20 The samples were taken 4 years apart. We were therefore able to estimate the time course of the BMs and the BM type (Figure 1).

-

4.

Verification of “real-world” practicality: Finally, we measured the BM candidates in an additional group of children with early stages of AS and similar diseases. Other nephropathies were also analyzed (in preparation).

Figure 1.

General time courses of disease biomarkers. There are several hypothetical BM types that are differently targeted by our approach. Type A: BMs applicable preclinically; increase indicates alterations starting in a preclinical stage and persisting under progression. Type B: truly preclinical BMs; indicating only preclinical alterations. Type C: early BMs; increase indicates alterations simultaneous with the development of early clinical signs, often overlooked or neglected (e.g., in AS, hematuria). Type D: late BMs; increase indicates subsequent alterations in manifested disease. This type (e.g., in AS, (micro)-albuminuria, decline of eGFR) is already in clinical use and was not part of our search. Type A and B were searched for in juvenile AS-mice (4 weeks13) and AS-dogs (7 weeks). This search might also detect type C. Human samples usually come from different points of individual disease development. Their evaluation might therefore miss type B BMs. However, all BMs detected (A, B, or C) are likely to be more suitable for early diagnosis of kidney injury than those currently applied. AS, Alport syndrome; BM, biomarker.

In the proof-of-concept phase, we evaluated our BM candidates in dogs and humans by immunoassays. Our goals were to determine the ability of our proteomic strategy, to estimate the BM time courses, and the strength of their ability to discriminate between healthy and affected individuals.

Methods

Animals and Sampling Protocol

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Texas A&M University Laboratory Animal Care Committee. One author, MN sampled from 7-week old mixed-breed dogs with X-linked AS17 and unaffected littermates. Texas A&M University Animal Rearing Center raised the dogs. These dogs were not under any treatment. Collected EDTA-blood was placed on ice. For serum, whole blood was allowed to clot for at least 30 minutes. Urine was refrigerated. We centrifuged the plasma at 3220 g for 20 minutes at 4 °C, serum at this rate and at 20 °C, and urine at 453 g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. We then stored aliquots at −80 °C. We measured the protein-to-creatinine ratio and blood chemistry values using a Vitros 250 analyzer (Johnson & Johnson Co, Rochester, NY). And we measured urine values using the dipstick Multistix (Bayer Corp, Elkhart, IN).

Samples Used for Proteomic Search

Equal volumes of 1 plasma sample from each of 3 dogs were combined for each group (affected males [AM], carrier females [CF)], and unaffected siblings [NM, NF]). Each pool was prefractionated and subsequently analyzed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data of pooled dog samples used for mass spectrometry

| Pool | Litter | Pooled EDTA-plasma samples |

Laboratory data |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input for chromatographic pre-fractionation |

Urine |

Serum |

||||||

| Vol. (ml) | Protein (mg/ml) | Protein (mg) | UPC | Dipstick Blood | Creatinine mg/dl | Albumin g/dl | ||

| NM | 1, 2, 2 | 0.78 | 78.85 | 61.5 | 0.48 ± 0.41 | Tr, N, N | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 2.80 ± 0.08 |

| NF | 1, 3, 3 | 0.78 | 80.97 | 63.2 | 0.36 ± 0.34 | N, N, Tr | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 2.50 ± 0.14 |

| CF | 1, 3, 3 | 0.78 | 83.58 | 65.2 | 0.14 ± 0.11 | N, N, 1+ | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 2.50 ± 0.00 |

| AM | 1, 3, 3 | 0.78 | 79.27 | 61.8 | 0.92 ± 0.53 | 1+, 2+, Tr | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 2.53 ± 0.09 |

AM, affected male; CF, carrier female; N, negative; NF, unaffected female; NM, unaffected male; Vol., volume; Tr, trace; UPC, urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio.

Samples were obtained at week 7 of age.

Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

Our native prefractionation workflow followed21 (Supplementary Methods). The chromatographic distributions of proteins are shown in Supplementary Figures S1 to S3.

Selection of BM Candidates

BM candidates were selected from all identified protein chains after pairwise comparison of data of 2 dimensional-(2D-)subfractions from affected and nonaffected dogs. Peptides supporting proteins identified in 2D-subfractions from AM were compared with those of the homologous 2D-subfractions from NM by Sieve, as well as those from CF with those from NF. The quantifier “ratio” is related to the concentration quotient (AM/NM, CF/NF) and “hits” to the amount of the respective protein in these subfractions. Sieve data on each protein identified were sorted to our separation matrix by in-house macros to visualize the chromatographic distribution of altered protein variants according.21,22 Therefore, a BM was defined either by a >2-fold higher concentration based on the “overall trend” (Supplementary Methods, Formula 1) or by mean ratios, when we saw exclusive synergistic alterations. Alternatively, we defined a BM as a fraction out of an entire protein family by a >5-fold higher mean ratio in distinct clusters of subfractions, that is, a distinct strongly elevated variant (Figure 2).

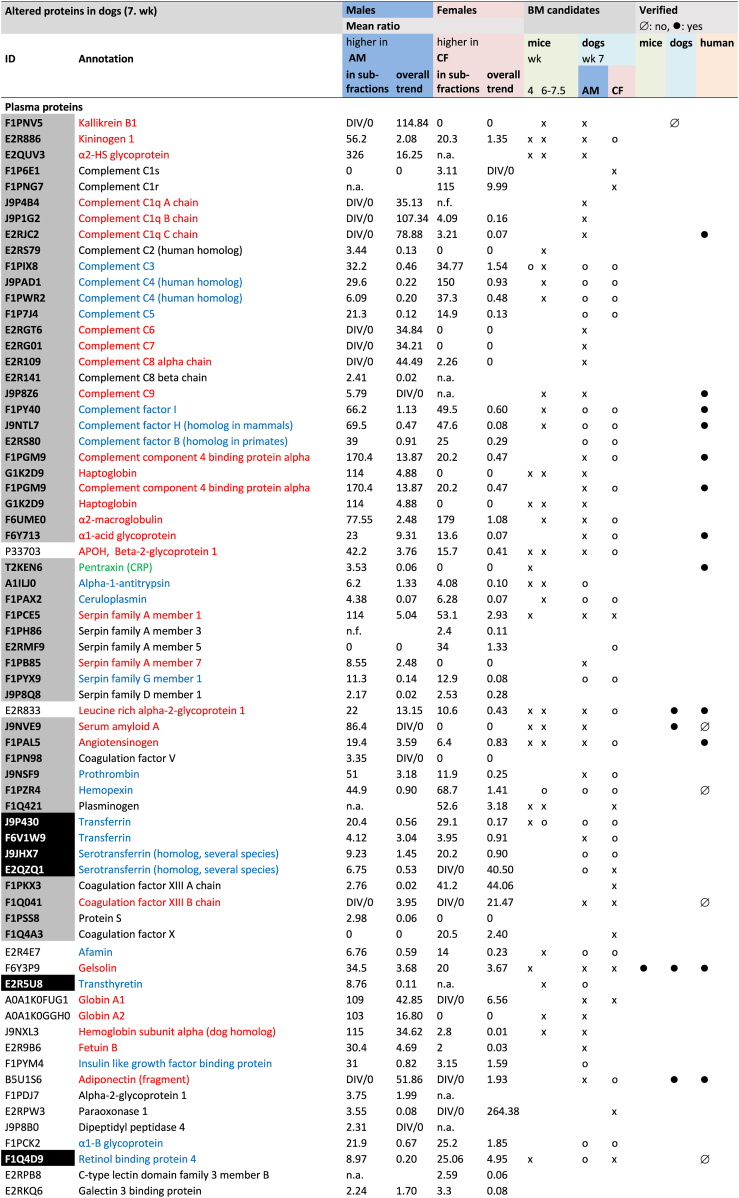

Figure 2.

Biomarker candidates identified by mass spectrometry. Criteria defining a biomarker: Biomarker selection in mice, see reference.13 BM candidates in dogs were by weighted mass spectrometric data (Supplementary Methods, Formula 1). Peptides supporting the proteins in a 2D-sub-fraction from AM were compared by Sieve with those of the homologous 2D-sub-fraction from NM as well as those from CF with those from NF. The quantifier “ratio” is related to the concentration quotient (AM/NM, CF/NF) of each specific protein in the sub-fractions compared. n.a., not altered; n.f., not found; 0, no cluster in this direction; x, overall trend higher in AM than in NM and in CF than in NF; o, increased parts/protein variants in AM and CF; DIV/0: no protein detected in healthy controls (no ratio can be given); mean ratio, mean of all ratios with synergistic alteration of the protein (AM/NM or CF/NF). Red: candidate BMs; blue: some proteoforms might serve as candidate BMs; green: candidate BMs in mice, criteria not fulfilled in dogs. Grey filling: positive APR; black filling: negative APR. Altogether, 124 protein chains were more abundant in affected than in unaffected dogs, either in males or females or both, and 74 proteins fulfilled the definition for a BM candidate. AM, affected male; APR, acute phase protein; BM, biomarker; CF, carrier female; NF, unaffected female; NM, unaffected male.

Analysis of Posttranslational Modifications

Kidney disease induces several metabolic changes. Therefore, we additionally analyzed a few posttranslational modifications (PTM) of highly abundant dog proteins to determine whether proteins were already metabolically altered in preclinical AS. The Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) performed this search21 (Supplementary Methods).

Proof-of-Concept

For proof-of-concept, it was also necessary to evaluate the differences in BM concentrations and to assess their sensitivity and specificity. We therefore measured several BMs by ELISA in samples from dogs and humans.

Dog Samples

We evaluated these features of BMs using samples from mixed-breed dogs. These dogs were of the same cohort as those used for proteomic search but not the same animals. However, the number of samples was insufficient for statistical analysis because the human COVID-19 pandemic during our research restricted access.

Human Samples

We used 3 sets of human samples. All storage and transport were at below −80°C.

Set 1 was of prospective longitudinal real-world clinical serum and urine samples from the multicenter trial “EARLY PRO-TECT Alport”20 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01485978, Table 2). Samples from each patient were obtained at 2 time points. The first point was during the very early stages of AS and the second about 4 years later.

Table 2.

Data from set 1; prospective samples (EARLY PRO-TECT Alport) from 35 male Alport patients

| Sampling | Age (yr, mean ± SD) | Age (yr, range) | ACI therapy (n) | Serum creatinine (mg/dl, mean ± SD) | Urine albumin (mg/g creatinine, mean ± SD) | Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals (N = 35) | n | |||||

| First | 8.9 ± 4.1 | 3–17 | 20 | 0.44 ± 0.15 | 293.0 ± 601.9 | 32 |

| Second | 12.5 ± 4.1 | 6–21 | 24 | 0.58 ± 0.19 | 578.9 ± 1107.7 | 33 |

| Genetic variants23 | ||||||

| Less severe (n = 7) | ||||||

| First | 10.3 ± 3.7 | 4–17 | 5 | 0.51 ± 0.10 | 16.2 ± 7.3 | 7 |

| Second | 13.6 ± 3.8 | 7–20 | 5 | 0.58 ± 0.13 | 14.8 ± 11.8 | 6 |

| Intermediate (n = 17) | ||||||

| First | 9.5 ± 4.3 | 3–17 | 6 | 0.43 ± 0.13 | 390.3 ± 789.8 | 15 |

| Second | 13.4 ± 4.3 | 6–21 | 10 | 0.62 ± 0.22 | 647.5 ± 1314.6 | 16 |

| Severe (n = 11) | ||||||

| First | 7.0 ± 3.0 | 3–13 | 9 | 0.38 ± 0.14 | 245.3 ± 391.8 | 10 |

| Second | 10.6 ± 3.0 | 7–17 | 9 | 0.51 ± 0.16 | 638.1 ± 683.9 | 11 |

ACI, angiotensin-converting-enzyme-inhibition.

Set 2 was obtained from the Jena University Hospital, Germany, with serum and urine samples from pediatric patients suffering from AS, including the Alport spectrum of thin basement membrane nephropathy, or benign familial hematuria. These diseases were diagnosed clinically by family history, ultrasound, histology, genetic analysis, or by established renal parameters. For controls, we took serum and urine samples using standard methods from children with no known nephropathy (ethical approval JUH: 2020-1800) (details in Table 3).

Table 3.

Basic and clinical characteristics in the study population and controls, i.e., sample sets 2 and 3

| Group | n | Gender | Age (yr) | BMI (SDS, z) | eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | Cystatin CGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | Cystatin C (serum) mg/l | Blood pressure syst. (SDS, z) | Blood pressure diast (SDS, z) | Serum creatinine (μM) | Urine albumin (mg/g creatinine) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 48 | Male | 10.3 (4.1, 3.1 to 17.1) | 0.220 (1.28, −2.50 to 3.68) | 145.6 (25.6) | 113.2 (23.1) | 0.87 (0.12) | 0.490 (0.997) | 0.274 (0.866) | 51.0 (15.8) | 6.9 (5.9) |

| Controls | 56 | Female | 10.3 (4.0, 3.5 to 16.7 | −0.064 (1.25, −3.44 to 2.90) | 153.4 (30.0) | 121.5 (22.5) | 0.81 (0.11) | 0.325 (1.00) | 0.409 (1.01) | 45.5 (12.7) | 11.1 (12.0) |

| Controls | 104 | 48 m/56f | 10.3 (4.0, 3.1 to 17.1) | 0.069 (1.264, −3.44 to 3.68) | 149.8 (28.2) | 117.7 (23.0) | 0.84 (0.12) | 0.404 (0.999) | 0.344 (0.943) | 48.1 (14.4) | 9.2 (9.9) |

| ASc, TBMN, BFH | 15 | 8 m/7 f | 12.8 (3.1) | 0.318 (1.131, −1.81 to 2.41) | 154.6 (22.9) | 117.6 (22.8) | 0.82 (0.11) | 0.658a (0.983) | 0.137 (0.536) | 52.6 (13.2) | 106.1b (285.2) |

AS, Alport syndrome; BMI, body mass index; BFH, benign familial hematuria; CGFR, calculated glomerular filtration rate; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SDS, standard deviation scores (SDS; also known as z-scores); TBMN, thin basement membrane nephropathy.

Unmarked values are not significantly different from the corresponding controls (patients versus healthy controls and females (f) versus males (m)). Healthy pediatric controls included 70 samples from the Leipzig Medical Biobank (Leipzig Research Center for Civilisation Diseases. LIFE-child (collection: 02/2014-11/2014)) and 34 pediatric controls from Jena (09/2020-09/2021). We SDS transformed BMI24 and blood pressure.25

The data are presented as means, SD and ranges (age, BMI).

P < 0.05 is considered significant.

P < 0.01 highly significant, Mann-Whitney, U-test.

Autosomal Alport syndrome (AS) and histologically determined AS without genetic information.

Set 3 was of pediatric control samples independently obtained from the Leipzig Medical Biobank (Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases, LIFE-child) (details in Table 3).

Evaluation by Immune Assays

All measurements were carried out in duplicates using commercial ELISA test kits (Supplementary Table S1). We initially tested a few samples to determine the measurable range and the dilutional linearity of each assay. We were unable to measure any promising BM candidates due to the limited availability or specificity of the test kits. Furthermore, it was not possible to apply all the immune assays to all samples because of the limited sample volumes.

Analysis of ELISA Results

The data were analyzed by SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Because the data distribution were nonnormal, we tested the similarity of medians using Kruskal-Wallis tests. We followed these by post hoc analyses using Mann-Whitney-U-test pairwise comparisons. The statistical significance was P < 0.05 (95% confidence interval). We correlated the immune reactivity of BMs with each other using SPSS (v. 27).

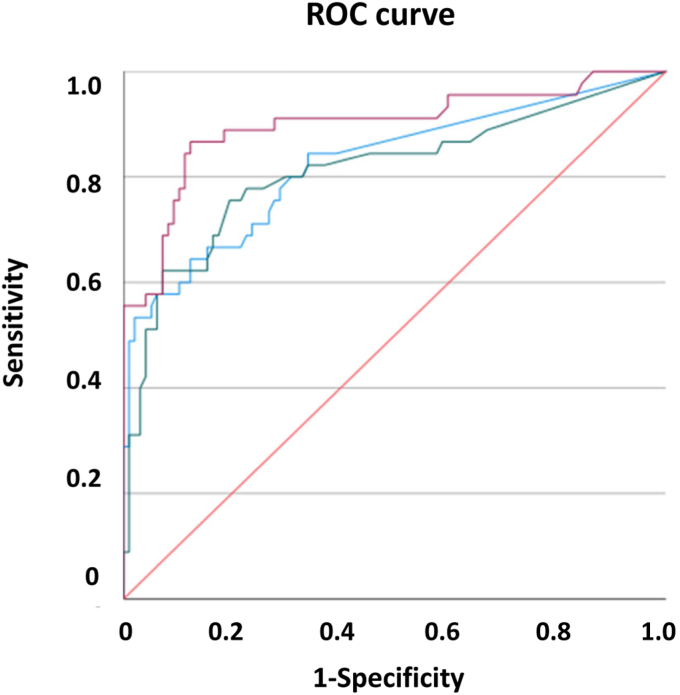

Moreover, we used correlation analyses with several clinical data and receiver operating characteristic curve analyses to assess the diagnostic values of each BM and BM combination. Accuracy was judged moderate for area under the curve 0.7 to 0.9 and high for area under the curve >0.9.26

Results

Discovery Phase: Proteomic Search in Blood Plasma From Dogs With Preclinical Stage AS

The global protein distribution after prefractionation is given (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). The high precision of our method21 allowed reliable comparisons between the constituents of subfractions from different samples.27 In total, using 2 analysis methods, we found 3115 protein chains using Proteome Discoverer, but 918 with Sieve (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The 3115 chains represented approximately 600 unique proteins and the 918 chains represented approximately 300 unique proteins. The majority of proteins showed several chromatographic clusters indicating the existence of diverse proteoforms with different degrees and directions of alteration in AS. Only a few were uniformly increased or reduced in affected versus nonaffected dogs (Supplementary Figures S3–S6, Supplementary Table S4).

In order to define BM candidates out of the list of altered proteins, we either selected spots with a mean ratio of ≥5.0 (Sieve) or, in the case of miscellaneous clusters, we applied formula 1 (Supplementary Methods) and accepted ≥2.0 as sufficient to define a BM candidate. Therefore, all clusters, both increased and reduced, were included in estimating a value for the global alteration of the protein family. By this procedure, we identified a total of 124 protein chains determining 74 proteins as BM candidates (Figure 2, Supplementary Table S4).

Several BM candidates were almost exclusively increased in AM, such as serum amyloid A, complement component C9, HABP2, collagen type XIII α1 chain (ColXIII), and the capping actin protein of the muscle Z-line alpha subunit. All other BM candidates showed miscellaneous alterations (Supplementary Figures S4–S6, Supplementary Table S4).

Adiponectin and complement C1q were higher in male dogs with AS (AM) than in controls, in overlapping chromatographic clusters (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S7). The α1 chain of type I collagen was more abundant in affected males and females, the α2 chain only in males than in controls. By sequence analysis, we detected only the c-terminal propeptides of both chains. ColXIII was more abundant in AM in several subfractions than in unaffected animals (Supplementary Figure S8). The sequence detected was located within the collagenous ectodomain. The unprocessed angiotensinogen was also higher in AM than in controls (Figure 2).

We next investigated PTMs. It is possible that disease alters these PTMs, thereby altering protein chromatographic profiles. We therefore analyzed PTMs of some of the highly abundant proteins. The major albumin and transferrin clusters did not differ between groups. However, some of their minor clusters differed in amount and in deamidation and carbamyolation rates. It is possible therefore that these minor cluster differences are early indications of disease (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Figures S10 and S11).

Validation in Dogs

We then validated the BMs by examining whether they were present in representative dogs with AS. However, it was only possible by ELISA, to quantify some of the BM candidates in dog samples. Of those we were able to quantify, the results of 7 were consistent with the mass spectrometric data. These 7 were leucine-rich alpha 2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1), gelsolin (GS), procollagen type I carboxy-terminal propeptide (PICP), ColXIII, serum amyloid A, and adiponectin (Supplementary Table S5). Although not comprehensive, these results confirm the reliability of our proteomic results.

Confirmation of Candidate BMs for Early Screening in Children With AS

Thirteen BMs in the blood and 14 BMs in urine were significantly higher from children at early stage AS than in healthy children (Table 4, Figure 3, Supplementary Figure S9). Of these 14 in urine, 3 allowed the identification of all the disease groups included. These were HABP2, complement factor H (CFH), and C4BP. A further 5 differed for 3 disease groups. These 5 were adiponectin, ColXIII, LRGP1, formin 1 (FMN), and fibrinogen γ-chain. Furthermore, it is notable that 8 urinary BMs even allowed discrimination between preclinical AS (less severe, compare Table 2) and controls. Because several BMs correlate with other BMs (Supplementary Table S6), we multiplied the correlated BMs in order to improve the significant differences between patients and controls. Indeed, the products of urinary BMs increased the overall discriminatory power (Table 5). As a consequence of this procedure, we were able to identify 19 combinations of BMs and 54 times when patients had significantly higher values than controls, and 11 combinations that distinguished preclinical AS (less severe, compare Table 2) from controls.

Table 4.

Significance levels (P-values) of BM concentrations in blood and urine different in patients and healthy controls

| BM |

Concentration range |

ASa, TBMN, BFH (set 2) |

ASb severity (set 1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less severe |

intermediate |

severe |

|||

| Serum | |||||

| n = 4–10 | n = 6–8 | n = 5–17 | n = 8–11 | ||

| ADP | ng/ml | ||||

| a1AGP | mg/ml | 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| AGT | ng/ml | 0.067 | |||

| ColXIII | ng/ml | <0.001 | 0.085 | ||

| GS | μg/ml | 0.020 | 0.024 | 0.009 | |

| LRGP1 | pg/ml | <0.001 | |||

| HABP2 | ng/ml | 0.046 | 0.008 | ||

| PICP | ng/ml | <0.001 | |||

| TGFß | ng/ml | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| VTN | μg/ml | 0.043 | |||

| C9 | ng/ml | 0.074 | |||

| C4BP | ng/ml | 0.011 | 0.040 | ||

| CRP | ng/ml | 0.084 | <0.001 | 0.005 | |

| LUM | ng/ml | ||||

| FMN | pg/ml | ||||

| CFH | ng/ml | 0.024 | 0.036 | 0.006 | |

| CFI | ng/ml | <0.001 | 0.007 | <0.001 | |

| FGG | ng/ml | ||||

| C1q | ng/ml | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.073 | |

| Urine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 10–13 | n = 8 | n = 14–16 | n = 8–11 | ||

| ADP | ng/mg c | <0.001 | <.001 | 0.016 | |

| a1AGP | ng/mg c | 0.093 | 0.093 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AGT | ng/mg c | 0.068 | |||

| ColXIII | ng/mg c | 0.015 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| GS | ng/mg c | ||||

| LRGP1 | ng/mg c | 0.012 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| HABP2 | ng/mg c | 0.001 | 0.010 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PICP | pg/mg c | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.072 | |

| TGFß | pg/mg c | ||||

| VTN | ng/mg c | ||||

| C9 | pg/mg c | 0.016 | |||

| C4BP | ng/mg c | <0.001 | 0.037 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CRP | pg/mg c | 0.062 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| CFH | ng/mg c | 0.033 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CFI | ng/mg c | 0.098 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| FMN | pg/mg c | 0.013 | 0.057 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| LUM | ng/mg c | ||||

| FGG | ng/mg c | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| C1q | ng/mg c | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

ADP, adiponectin; AGT, angiotensinogen; AS, Alport syndrome; BMI, body mass index; BFH, benign familial hematuria; CFH, complement factor H; CFI, complement factor I; CGFR, calculated glomerular filtration rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FGG, fibrinogen γ-chain; FMN, complement factor I; LUM, lumican; PICP, procollagen type I carboxy-terminal propeptide; SDS, standard deviation scores (SDS; also known as z-scores); TBMN, thin basement membrane nephropathy; VTN, vitronectin.

The number of patients differs from BM parameter to parameter, because we were unable to measure all parameters in all patients. Insufficient volumes of some samples caused this. n: counts of patient values (min-max) included. P < 0.05 is considered significant, P < 0.01 highly significant, (Mann-Whitney U-test). Some P-values of 0.05 to 0.10 included to show tendencies. All other comparisons yield nonsignificant differences. Bold: favored BMs. Urinary concentrations are normalized by creatinine (c). Healthy controls: n = 11–25 for serum; n = 86–101 for urine.

Autosomal Alport syndrome (AS) and histologically determined AS without genetic information.

Genetic characterized AS (set 1, first samples).

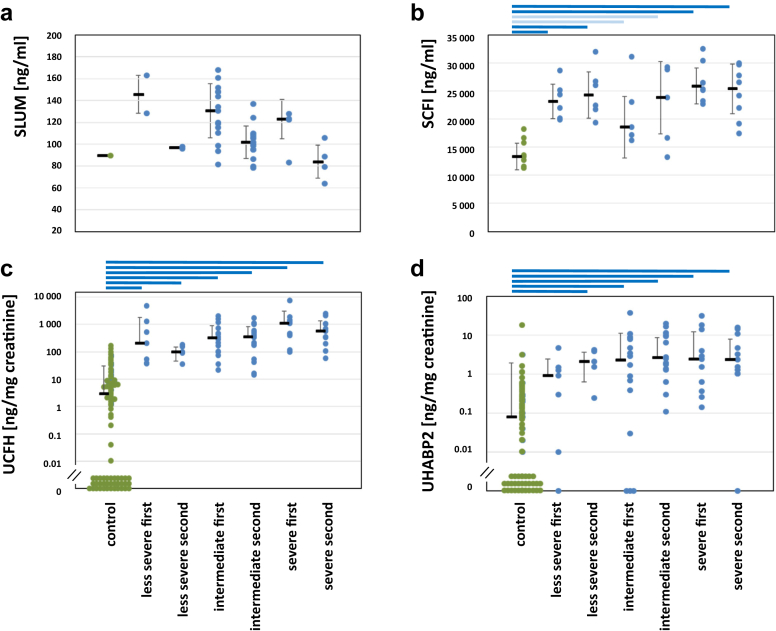

Figure 3.

Comparison of BM concentrations in sample set 1 from patients with AS and healthy controls. Second samples were taken about 4 years after the first. Significances: P < 0.05 (light blue bars); P < 0.01 (dark blue bars); all other not significant. c, d: Values below the detection limit (= 0) are arranged close to the abscissa for visualization. (a) Lumican (LUM) in serum. Due to the small number of samples, dots indicate tendency. (b) Complement factor I (CFI) in serum. (c) Complement factor H (CFH) in urine; (d) Hyaluronan binding protein 2 (HABP2) in urine.

Table 5.

Significance levels (P-values) of combined BM concentrations in urine that are different in patients and healthy controls

| Product of BM | ASa, TBMN, BFH (set 2) |

ASb (set 1) less severe |

Intermediate |

Severe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 5–10 | n = 8 | n = 14–16 | n = 7–11 | |

| ADP × PICP | 0.012 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.094 |

| ADP × C9 | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| ADP × C4BP | <0.001 | 0.040 | <0.001 | |

| AGT × GS | ||||

| AGT × C9 | ||||

| ColXIII × C4BP | 0.002 | 0.076 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ColXIII × FMN | 0.002 | 0.052 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| GS × CFH | 0.068 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| GS × C9 | 0.098 | |||

| GS × VTN | ||||

| GS × CFI | 0.033 | 0.005 | ||

| LRGP1 × C1q | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| HABP2 × TGFß | 0.031 | 0.030 | ||

| HABP2 × FGG | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | |

| VTN × AGT | ||||

| VTN × C9 | ||||

| VTN × CFI | 0.019 | |||

| C9 × CFH | 0.008 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| CRP × C1q | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

| CFH × CFI | 0.029 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CFH × FGG | 0.008 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.056 |

| CFI × FGG | 0.038 | 0.046 | <0.001 | |

| CFI × a1AGP | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| CFI × GS | 0.033 | 0.005 | ||

| FMN × FGG | 0.008 | 0.005 | <0.001 | |

| ColXIII × C4BP × HABP2 | 0.003 | 0.012 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

ADP, adiponectin; AGT, angiotensinogen; BFH, benign familial hematuria; PICP, procollagen type I carboxy-terminal propeptide; TBMN, thin basement membrane nephropathy.

The number of patients differ from BM parameter to parameter, because we were unable to measure all parameters in all patients. Insufficient volumes of some samples caused this. n: counts of patient values (min-max) included. P < 0.05 is considered significant, P < 0.01 highly significant, (Mann-Whitney U-test). Some P-values 0.05 to 0.10 are included to show tendencies. All other comparisons yield nonsignificant differences. Bold: favored BMs. Urinary concentrations are normalized by creatinine (c). Healthy controls (n = 84–99).

Autosomal Alport syndrome (AS) and histologically determined AS without genetic information.

Genetic characterized AS (set 1, first samples).

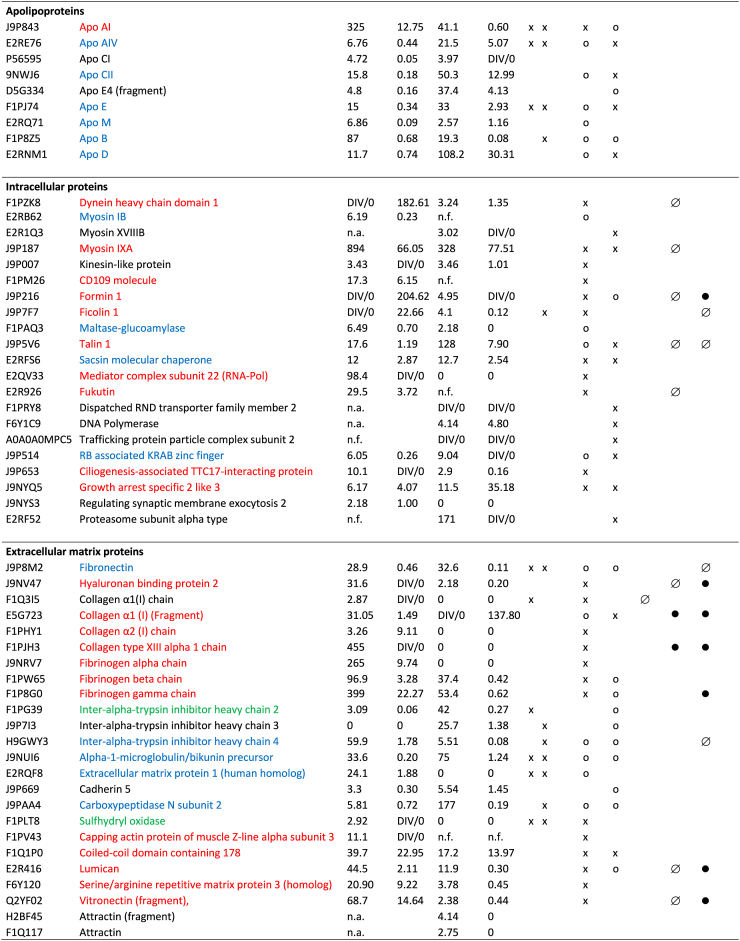

Verification of “Real-World” Practicality

To verify our BM candidates for “real-world” practicality, we also examined whether BMs occurred in an additional group of children with early stage AS or other causes of microhematuria (Table 3). The receiver operating characteristic curve analyses indicated the diagnostic value of our BMs. For this analysis, the area under the curve were >0.800 for serum TGF-ß1, for complement factor I (CFI), for urinary ColXIII, HABP2, CFH, C4BP, and combinations thereof. They also exhibited reliable sensitivity and false positive rate, either alone or in combination (Figure 4 and Table 6) like with set 1 (Supplementary Table S10). Albuminuria did not correlate with any of our BM candidates, only urinary lumican (LUM) did (Supplementary Tables S7–S9). Urinary LUM also correlated with urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio at progression of disease (4 years later). Our early BM candidates did not correlate with the parameters of late stage kidney failure, such as glomerular filtration rate, or with indicators of inflammation, that is, C-reactive protein (CRP). We are therefore able to confirm the real world practicality of several BMs for diagnostic purposes.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of urinary BMs, comparison of patients with Alport syndrome, thin basement membrane nephropathy, and benign familial hematuria (sample set 2) with controls. Blue: Collagen XIII (ColXIII); green: hyaluronan binding protein 2 (HABP2); magenta: complement C4 binding protein (C4BP); red: reference line. BM, biomarker.

Table 6.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, comparison of patients with aAlport syndrome, thin basement membrane nephropathy, and benign familial hematuria (set 2) with controls

| BM | Cut-off | Sensitivity | 1-specificity | AUC | BM×BM | Cut-off | Sensitivity | 1-specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | |||||||||

| TGFß | 30.82 | 0.733 | 0.158 | 0.830 | |||||

| CFI | 16760 | 0.769 | 0.111 | 0.846 | |||||

| Urine | |||||||||

| ColXIII | 0.98 | 0.617 | 0.131 | 0.817 | ColXIII×FMN | 13.75 | 0.725 | 0.232 | 0.796 |

| HABP2 | 0.62 | 0.596 | 0.072 | 0.808 | C4BP×ColXIII | 5.20 | 0.723 | 0.102 | 0.856 |

| C4BP | 4.04 | 0.894 | 0.192 | 0.898 | GS×CFH | 579.6 | 0.745 | 0.253 | 0.815 |

| CRP | 4.29 | 0.674 | 0.210 | 0.765 | LRGP1×C1q | 0.90 | 0.667 | 0.105 | 0.801 |

| CFH | 21.72 | 0.851 | 0.153 | 0.903 | C9×CFH | 3058 | 0.617 | 0.121 | 0.799 |

| CFI | 1.07 | 0.596 | 0.224 | 0.718 | CRP×C1q | 0.72 | 0.694 | 0.221 | 0.806 |

| FGG | 183 | 0.591 | 0.1 | 0.753 | CFH×CFI | 20.74 | 0.702 | 0.182 | 0.850 |

| C4BP×ColXIII×HABP2 | 2.16 | 0.652 | 0.052 | 0.819 | |||||

AUC, area under the curve; CRP, C-reactive protein; FGG, fibrinogen γ-chain.

Concentration ranges of BMs: Serum: TGF-ß1 and CFI, ng/mL. Urine: ColXIII, HABP2, C4BP, CFH, CFI, FGG, GS, LRGP1, and C1q, ng/mg creatinine; CRP, C9 and FMN, pg/mg creatinine.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis by SPSS (cf. Methods section). Only BMs with AUC >0.700 are shown.

Autosomal Alport syndrome (AS) and histologically determined AS without genetic information.

Discussion

Our search included preclinical mice and dogs with AS, a unique cohort of children from the EARLY PRO-TECT Alport trial, and from children with early stages of AS and similar glomerular diseases.28,29

After nondenaturing 2D-prefractionation, the majority of proteins appeared as a natural multitude of chromatographic clusters including disease specific proteoforms (Supplementary Figures S5–S7).13,21 Thus, one BM-cluster did not reflect the general deviation of a particular protein-family, rather the most meaningful variant out of many. Different clusters reflect heterogeneity, likely due to diverse PTM.21 Unfortunately, most commercial ELISAs are not variant-selective, as is required. Thus, out of all altered proteins, we selected only BM candidates with considerable global elevation derived from weighted mass spectrometric data, and for which an ELISA was available.

Because the glomerulus has close contact with both blood and urine, components are able to escape from the glomerulus into both fluids.13 Although identified in blood, the plurality of proteoforms might mask strongly altered glomerular protein variants (as discussed above). In urine, however, we were able to detect, immunologically, the proteoform that, very probably, leaks from the injured glomerulus. This was even possible using nonselective ELISA. Therefore, urine, particularly useful in pediatrics, might better mirror glomerular disturbances without accompanying variants. This was confirmed by our ELISA results.

Our study uncovered several preclinical BMs for AS (type A and B, Figure 1). We identified a variety of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, acute phase reactants, apo-lipoproteins, cellular and cytoskeletal proteins (Figure 2). For example, α2-macroglobulin, α1-acid glycoprotein and LRG1 are similarly increased in both males and females, as well as several serpins, adiponectin, GS, and myosin IXA. Others were differently altered reflecting either gender or stage related differences. In accordance with preclinical mice with AS,13 preclinical dogs with AS show neither elevated markers of advanced CKD nor of acute kidney injury.30, 31, 32, 33

C-reactive protein (pentraxin), the main acute phase reactants in dogs,32 was only minimally elevated, supporting a lack of systemic inflammation at this early stage of the disease. Several other acute phase reactants were less in affected dogs than in controls or unaltered. Some negative acute phase reactants (e.g., transferrin), however, appeared to be greater. Therefore, the situation in dogs is similar to that in mice.13 Typical GBM components,34, 35, 36 however, were greater in AS (e.g., fibrinogen γ-chain, fibronectin, LUM, vitronectin [VTN], and HABP2). There were no peptides from type IV collagens. Our findings accord with the elevated expression of type I collagen in dogs and mice with AS.13,37 During collagen processing, the fragment PICP is removed by ADAMTS. PICP is indicative for early ECM remodeling and fibrosis.38, 39, 40, 41, 42 We retroactively identified 5 peptides in AS mice that align as precisely with murine PICP just as the canine sequences align with canine PICP. Moreover, several members of the ADAMTS-family are very homologous to ADAMs, including ADAM8,43 which was identified in humans with later stages of AS.44,45 Despite the significant deviation (Tables 4 and 5, and Supplementary Table S10), the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis shows urinary PICP appear insufficient for clinical use.

The transmembrane protein ColXIII is upregulated in AS.46 Its ectodomain interacts with several matrix components and is released by proteases.47, 48, 49 Therefore, this BM candidate appeared as one of the most promising BMs (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6).

Hyaluronan is an important component of the filtration barrier and interstitial renal water reabsorption mechanism.50, 51, 52 HABP2 is crucial for hyaluronan metabolism, in tissue homeostasis, and inflammation,50,53 and has enzymatic and regulatory activities.54 In children with AS, we verified HABP2 as one of the most promising early BMs.

The plurality of ECM components indicate early remodeling activity probably driven by TGF-ß1.55 Due to the renal increase of TGF-ß1 mRNA in dogs at late stages of AS,7,56, 57, 58, 59 of urinary TGF-ß1 in children with AS,31 and of TGF-ß1 in blood (Table 4), this mediator indicates progression.

Complement C1q and adiponectin are soluble defense collagens and are involved in repair and tissue homeostasis, with adiponectin also having antifibrotic effects.60,61 There are increased amounts of adiponectin in a variety of CKDs, including focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and lupus nephritis.62, 63, 64, 65 These increased amounts of adiponectin seem to indicate progression of CKD, rather than being disease specific.66 Our data are the first report of early alterations of adiponectin (Tables 4 and 5). However, in the preclinical stages of AS it has insufficient discriminatory power.

We evaluated the γ-chain of fibrinogen because it was the most elevated in AM (Figure 2). Fibrinogen is an intrinsic constituent of the GBM and acts as a hyaluronan-binding protein. It is intrinsically linked to blood coagulation and tissue fibrosis and is upregulated in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.34,67, 68, 69 And, urinary fibrinogen γ-chain has a high discriminatory score both alone and, even more clearly, combined with other BMs (Tables 5 and 6, and Supplementary Table S10).

Out of a group of regulatory complement components, C4BP has various roles such as cofactor for CFI-mediated C4b inactivation, inhibiting apoptosis, and inhibiting DNA release from necrotic cells.70,71 C4BP interacts with various regulatory molecules (including C-reactive protein, C1q, ficolins, CFH, and CFI, which we also identified as BM candidates), modifying the response to cell damage or apoptosis.72,73 These regulatory proteins are expressed in the podocytes, cells key to AS.74 CFI, CFH, and C4BP are high in dogs with AS (Figure 2) as well as in urine from children with AS (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, and Supplementary Table S10).

From the family of leucine-rich repeat proteins, we identified LUM and LRGP1 as early BM candidates. These proteins are involved in protein interactions, inflammation, signaling, and cell adhesion.75,76 In the kidney, LUM belongs to the ECM network, whereas intracellularly LRG1 prevents apoptosis and extracellularly modulates TGF-β1-signaling. LRG1 therefore plays a distinct role in tubular injury and lupus nephritis.77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82 LUM and LRGP1 are upregulated in AM, as in mice with AS.13 In urine from children with AS, we were able to verify LRG1 by ELISA, but unable to verify LUM. However, in set 1, LUM declined during disease progression in all severity groups and is therefore a convenient BM of type B (Figure 1) in the same way as PICP and C1q, (Supplementary Figure S9).

In previous studies, reduced levels of GS, an actin-interacting protein,83,84 are linked to organ injury including CKD, correlating with disease progress and mortality.85, 86, 87 We previously identified GS as a BM in mice with AS.13 Dogs with early AS have heterogeneous results after mass spectrometry (Supplementary Figure S6 and Figure 2). However, we were able to observe slightly higher values in serum from affected dogs (Supplementary Table S5) and in urine from children with AS (Tables 4 and 5).

Several other proteins which are crucial for podocytes, such as dynein, myosin IXA, FMN, talin 1, sacsin, and fukutin, were upregulated in AM.88 However, we found no reliable ELISAs for these dog proteins. Therefore, we only analyzed the human samples with talin and FMN. FMN, validated, belongs to a family of proteins involved in the polymerization of actin89 but is not known as a BM for AS. FMN is notably higher in urine than blood but only significantly so in children with early stages of intermediate and severe AS and in combination with ColXIII (Tables 5 and 6, and Supplementary Figure S9).

Although increased in our study group vitronectin,34,49,90, 91, 92, 93 complement component C9,34 and angiotensinogen have insufficient diagnostic power (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6).

Several minor subfractions of albumin and transferrin showed increased deamidation rates in AM, probably by transglutaminase activities.94,95 Transglutaminases also catalyze crosslinking of ECM molecules. Coagulation factor XIII, which also has transglutaminase activity, is increased in AM (Figure 2), and possibly responsible for these modifications.96 We detected minor parts of albumin carbamoylated already in preclinical dogs with AS confirming21 although that this nonenzymatic modification was associated with advanced CKD.97 Their use for diagnostics however requires PTM-specific ELISA.

Our most promising BMs did not correlate with individual and clinical parameters (Supplementary Results). Therefore, our BMs reveal an additional benefit and no special cut-offs must be considered in clinical practice.

Conclusions

We identified several promising real-world BM candidates for very early stages of AS. We included the requirement that diagnostic BMs must cover a wide window of opportunity because the exact stage of AS in a child depends on multiple factors such as the type and location of the mutation, age, diet, protein and salt intake, and other environmental factors. Preclinical glomerular injury in AS is indicated by BMs of 3 different origins as follows: (i) ColXIII, a membrane protein from glomerular endothelial cells; (ii) HABP2, a constituent from the GBM; and (iii) C4BP from podocytes. Moreover, we were also able to establish several other components usable for early diagnostics of AS, such as FMN, LRGP1, and GS (from injured or destroyed cells), fibrinogen γ-chain (from ECM), C-reactive protein, CFH, CFI (regulatory complement components), as well as complement factors C1q and complement component C9.

Although our results are statistically supported, and promising, we had to obtain them from a limited number of samples. This was because of the rarity of the diseases and the pandemic conditions during our research. Further studies therefore need to include larger numbers of samples and ensure similar sample numbers in the different BM groups. Such further studies should also focus on the time course of our BM candidates during disease progression. For application in the real world, we suggest using a combination of diagnostic BMs rather than single parameters. Furthermore, in the near future, our BMs may also serve as prognostic markers and markers of response to nephroprotective therapy.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicting interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01KG1104), German Research Foundation (GR1852/6-1), Thuringia Ministry for Education, Science, and Culture, and the EFRE-fund (2013 FE 9075), and XLifeSciences (X-Kidneys, DD 0290-20). English editing was done by Dr. A. J. Davis of English Experience Language Services, Goettingen, edited versions of the manuscript during its preparation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

HR and OG designed the study and wrote the manuscript. MN conducted animal breeding and analysis, and provided dog samples. HR and BT performed mass spectrometric analysis, major parts of data analysis, ELISAs and statistical analysis. AL analyzed parts of mass spectrometric data. JS, OM, FW, AD, JB, DR, WK, and UJ-K provided clinical samples from children. All authors interpreted the results, critically drafted and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Footnotes

Figure S1. Chromatograms of dog serum proteins after native size exclusion chromatography (1D-SEC).

Figure S2. Global protein distribution after anion exchange chromatography (2D-AEC).

Figure S3. Distribution of 2 examples of plasma proteins from NM after 2D-AEC.

Figure S4. Distribution of serum amyloid after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometry identification of its peptides as example of a uniformly altered protein.

Figure S5. Distribution of α1B-glycoprotein after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric identification of its peptides as example of a protein with several proteoforms with different degrees and direction of alteration under AS.

Figure S6. Distribution of gelsolin after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric identification of its peptides as example of a second protein with several proteoforms with different degrees and direction of alteration under AS.

Figure S7. Distribution of biomarker candidates, adiponectin and the complement component C1q after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric comparison of their peptides in AM to NM.

Figure S8. Distribution of the biomarker candidate ColXIII after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric comparison of its peptides in AM to NM.

Figure S9. Comparison of the concentrations of biomarker candidates in serum and urine from patients (set 1 and set 2) and controls.

Figure S10. Proteoforms and PTM of albumin.

Figure S11. Proteoforms and PTM of transferrin.

Table S1. Specification of ELISA-Test kits applied to dog and human samples.

Table S2. List of protein chains identified by the Proteome Discoverer in 4 sample pools of blood plasma from dogs.

Table S3. List of protein chains identified by the Sieve in 4 sample pools of blood plasma from dogs.

Table S4. Mass spectrometric identified biomarker candidates.

Table S5. Concentrations of some biomarker candidates determined by ELISA in dog samples.

Table S6. Correlation of biomarker concentrations in urine one with each other’s.

Table S7. Correlation of serum and urinary biomarker candidates with urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and serum creatinine in patients with AS and similar diseases.

Table S8. Correlation of serum and urinary biomarker candidates with eGFR and cGFR in patients with AS and similar diseases.

Table S9. Correlation of serum and urinary biomarker candidates with serum C-reactive protein in patients with AS and similar diseases.

Table S10. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, comparison of patients with AS (set1, first visit) with controls.

STARD Checklist.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Chromatograms of dog serum proteins after native size exclusion chromatography (1D-SEC).

Figure S2. Global protein distribution after anion exchange chromatography (2D-AEC).

Figure S3. Distribution of 2 examples of plasma proteins from NM after 2D-AEC.

Figure S4. Distribution of serum amyloid after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometry identification of its peptides as example of a uniformly altered protein.

Figure S5. Distribution of α1B-glycoprotein after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric identification of its peptides as example of a protein with several proteoforms with different degrees and direction of alteration under AS.

Figure S6. Distribution of gelsolin after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric identification of its peptides as example of a second protein with several proteoforms with different degrees and direction of alteration under AS.

Figure S7. Distribution of biomarker candidates, adiponectin and the complement component C1q after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric comparison of their peptides in AM to NM.

Figure S8. Distribution of the biomarker candidate ColXIII after 2D-AEC and mass spectrometric comparison of its peptides in AM to NM.

Figure S9. Comparison of the concentrations of biomarker candidates in serum and urine from patients (set 1 and set 2) and controls.

Figure S10. Proteoforms and PTM of albumin.

Figure S11. Proteoforms and PTM of transferrin.

Table S1. Specification of ELISA-Test kits applied to dog and human samples.

Table S2. List of protein chains identified by the Proteome Discoverer in 4 sample pools of blood plasma from dogs.

Table S3. List of protein chains identified by the Sieve in 4 sample pools of blood plasma from dogs.

Table S4. Mass spectrometric identified biomarker candidates.

Table S5. Concentrations of some biomarker candidates determined by ELISA in dog samples.

Table S6. Correlation of biomarker concentrations in urine one with each other’s.

Table S7. Correlation of serum and urinary biomarker candidates with urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and serum creatinine in patients with AS and similar diseases.

Table S8. Correlation of serum and urinary biomarker candidates with eGFR and cGFR in patients with AS and similar diseases.

Table S9. Correlation of serum and urinary biomarker candidates with serum C-reactive protein in patients with AS and similar diseases.

Table S10. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, comparison of patients with AS (set1, first visit) with controls.

STARD Checklist.

References

- 1.Kashtan C.E. Alport syndrome: achieving early diagnosis and treatment. Am J Kidney. 2021;77:272–279. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolaou O., Kousios A., Sokratous K., et al. Alport syndrome: proteomic analysis identifies early molecular pathway alterations in Col4a3 knock out mice. Nephrol (Carlton) 2020;25:937–949. doi: 10.1111/nep.13764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen N.T., Bae E.H., Do L.N., Nguyen T.A., Park I., Shin S.S. In vivo assessment of metabolic abnormality in Alport syndrome using hyperpolarized [1-(13)C] pyruvate MR spectroscopic imaging. Metabolites. 2021;11:222. doi: 10.3390/metabo11040222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding F., Wickman L., Wang S.Q., et al. Accelerated podocyte detachment and progressive podocyte loss from glomeruli with age in Alport syndrome. Kidney Int. 2017;92:1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo J., Song W., Boulanger J., et al. Dysregulated expression of microRNA-21 and disease-related genes in human patients and in a mouse model of Alport syndrome. Hum Gene Ther. 2019;30:865–881. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedrosa A.L., Bitencourt L., Paranhos R.M., Leitao C.A., Ferreira G.C., Simoes E.S.A.C. Alport syndrome: a comprehensive review on genetics, pathophysiology, histology, clinical, and therapeutic perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:5602–5624. doi: 10.2174/0929867328666210108113500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark S.D., Song W.P., Cianciolo R., Lees G., Nabity M., Liu S.G. Abnormal expression of miR-21 in kidney tissue of dogs with X-linked hereditary nephropathy: a canine model of chronic kidney disease. Vet Pathol. 2019;56:93–105. doi: 10.1177/0300985818806050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savige J., Ariani F., Mari F., et al. Expert consensus guidelines for the genetic diagnosis of Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:1175–1189. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-3985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torra R., Furlano M. New therapeutic options for Alport syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34:1272–1279. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashtan C.E., Ding J., Gregory M., et al. Clinical practice recommendations for the treatment of Alport syndrome: a statement of the Alport Syndrome Research Collaborative. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:5–11. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2138-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross O., Licht C., Anders H.J., et al. Early angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in Alport syndrome delays renal failure and improves life expectancy. Kidney Int. 2012;81:494–501. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross O., Friede T., Hilgers R., et al. Safety and efficacy of the ACE-inhibitor ramipril in Alport syndrome: the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III EARLY PRO-TECT alport trial in pediatric patients. ISRN Pediatr. 2012;2012 doi: 10.5402/2012/436046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muckova P., Wendler S., Rubel D., et al. Preclinical alterations in the serum of COL(IV)A3(-)/(-) mice as early biomarkers of Alport syndrome. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:5202–5214. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashtan C.E. Animal models of Alport syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1359–1362. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.8.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorner P.S. Alport syndrome and thin basement membrane nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;106:c82–c88. doi: 10.1159/000101802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox M.L., Lees G.E., Kashtan C.E., Murphy K.E. Genetic cause of X-linked Alport syndrome in a family of domestic dogs. Mamm Genome. 2003;14:396–403. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-2253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lees G.E. Kidney diseases caused by glomerular basement membrane type IV collagen defects in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2013;23:184–193. doi: 10.1111/vec.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grodecki K.M., Gains M.J., Baumal R., et al. Treatment of X-linked hereditary nephritis in Samoyed dogs with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. J Comp Pathol. 1997;117:209–225. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(97)80016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross O., Beirowski B., Koepke M.L., et al. Preemptive ramipril therapy delays renal failure and reduces renal fibrosis in COL4A3-knockout mice with Alport syndrome. Kidney Int. 2003;63:438–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross O., Tonshoff B., Weber L.T., et al. A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial with open-arm comparison indicates safety and efficacy of nephroprotective therapy with ramipril in children with Alport’s syndrome. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1275–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhode H., Muckova P., Buchler R., et al. A next generation setup for pre-fractionation of non-denatured proteins reveals diverse albumin proteoforms each carrying several post-translational modifications. Sci Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48278-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchler R., Wendler S., Muckova P., Grosskreutz J., Rhode H. The intricacy of biomarker complexity-the identification of a genuine proteomic biomarker is more complicated than believed. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2016;10:1073–1076. doi: 10.1002/prca.201600067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boeckhaus J., Hoefele J., Riedhammer K.M., et al. Precise variant interpretation, phenotype ascertainment, and genotype-phenotype correlation of children in the EARLY PRO-TECT Alport trial. Clin Genet. 2021;99:143–156. doi: 10.1111/cge.13861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kromeyer-Hauschild K., Wabitsch M., Kunze D., et al. Perzentile für den Body-mass Index für das Kindes- und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener Deutscher Stichproben. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2001;149:807–818. doi: 10.1007/s001120170107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. US Department of Health And Human Services. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/hbp_ped.pdf Published 2005.

- 26.Swets J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3287615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruger T., Lehmann T., Rhode H. Effect of quality characteristics of single sample preparation steps in the precision and coverage of proteomic studies--a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;776:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hastings M.C., Rizk D.V., Kiryluk K., et al. IgA vasculitis with nephritis: update of pathogenesis with clinical implications. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;37:719–733. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-04950-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koopman J.J.E., van Essen M.F., Rennke H.G., de Vries A.P.J., van Kooten C., de Vries A.P.J., van Kooten C. Deposition of the membrane attack complex in healthy and diseased human kidneys. Front Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.599974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Argyropoulos C.P., Chen S.S., Ng Y.H., et al. Rediscovering beta-2 microglobulin as a biomarker across the spectrum of kidney diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017;4:73. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chimenz R., Chirico V., Basile P., et al. HMGB-1 and TGFbeta-1 highlight immuno-inflammatory and fibrotic processes before proteinuria onset in pediatric patients with Alport syndrome. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1915–1924. doi: 10.1007/s40620-021-01015-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhama K., Latheef S.K., Dadar M., et al. Biomarkers in stress related diseases/disorders: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic values. Front Mol Biosci. 2019;6:91. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong J., Yang H., Kon V. Kidney as modulator and target of “good/bad” HDL. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:1683–1695. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lennon R., Byron A., Humphries J.D., et al. Global analysis reveals the complexity of the human glomerular extracellular matrix. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:939–951. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013030233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borza D.B. Glomerular basement membrane heparan sulfate in health and disease: a regulator of local complement activation. Matrix Biol. 2017;57-58:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hobeika L., Barati M.T., Caster D.J., McLeish K.R., Merchant M.L. Characterization of glomerular extracellular matrix by proteomic analysis of laser-captured microdissected glomeruli. Kidney Int. 2017;91:501–511. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naylor R.W., Morais M., Lennon R. Complexities of the glomerular basement membrane. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17:112–127. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chalikias G.K., Tziakas D.N. Biomarkers of the extracellular matrix and of collagen fragments. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;443:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKleroy W., Lee T.H., Atabai K. Always cleave up your mess: targeting collagen degradation to treat tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L709–L721. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00418.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bella J., Hulmes D.J. Fibrillar collagens. Subcell Biochem. 2017;82:457–490. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-49674-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kisling A., Lust R.M., Katwa L.C. What is the role of peptide fragments of collagen I and IV in health and disease? Life Sci. 2019;228:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bulow R.D., Boor P. Extracellular matrix in kidney fibrosis: more than just a scaffold. J Histochem Cytochem. 2019;67:643–661. doi: 10.1369/0022155419849388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong S., Khalil R.A. A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase (ADAM) and ADAM with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) family in vascular biology and disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;164:188–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pohl M., Danz K., Gross O., et al. Diagnosis of Alport syndrome--search for proteomic biomarkers in body fluids. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:2117–2123. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mischak H. Pro: urine proteomics as a liquid kidney biopsy: no more kidney punctures!. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:532–537. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dennis J., Meehan D.T., Delimont D., et al. Collagen XIII induced in vascular endothelium mediates alpha1beta1 integrin-dependent transmigration of monocytes in renal fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2527–2540. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heikkinen A., Tu H., Pihlajaniemi T. Collagen XIII: a type II transmembrane protein with relevance to musculoskeletal tissues, microvessels and inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tu H., Sasaki T., Snellman A., et al. The type XIII collagen ectodomain is a 150-nm rod and capable of binding to fibronectin, nidogen-2, perlecan, and heparin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23092–23099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preissner K.T., Reuning U. Vitronectin in vascular context: facets of a multitalented matricellular protein. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:408–424. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1276590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dane M.J., van den Berg B.M., Avramut M.C., et al. Glomerular endothelial surface layer acts as a barrier against albumin filtration. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1532–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stridh S., Palm F., Hansell P. Renal interstitial hyaluronan: functional aspects during normal and pathological conditions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R1235–R1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00332.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lennon F.E., Singleton P.A. Hyaluronan regulation of vascular integrity. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1:200–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lennon F.E., Singleton P.A. Role of hyaluronan and hyaluronan-binding proteins in lung pathobiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L137–L147. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeerleder S. Factor VII-activating protease: hemostatic protein or immune regulator? Semin Thromb Hemost. 2018;44:151–158. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sayers R., Kalluri R., Rodgers K.D., Shield C.F., Meehan D.T., Cosgrove D. Role for transforming growth factor-beta1 in alport renal disease progression. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1662–1673. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang A.S., Hathaway C.K., Smithies O., Kakoki M. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 and diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol-Ren. 2016;310:F689–F696. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00502.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meng X.M., Nikolic-Paterson D.J., Lan H.Y. TGF-beta: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:325–338. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khalili M., Bonnefoy A., Genest D.S., Quadri J., Rioux J.P., Troyanov S. Clinical use of complement, inflammation, and fibrosis biomarkers in autoimmune glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grenda R., Wuhl E., Litwin M., et al. Urinary excretion of endothelin-1 (ET-1), transforming growth factor- beta1 (TGF- beta1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165) in paediatric chronic kidney diseases: results of the Escape trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3487–3494. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Casals C., Garcia-Fojeda B., Minutti C.M. Soluble defense collagens: sweeping up immune threats. Mol Immunol. 2019;112:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jasinski-Bergner S., Buttner M., Quandt D., Seliger B., Kielstein H. Adiponectin and its receptors are differentially expressed in human tissues and cell lines of distinct origin. Obes Facts. 2017;10:569–583. doi: 10.1159/000481732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sethna C.B., Boone V., Kwok J., Jun D., Trachtman H. Adiponectin in children and young adults with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:1977–1985. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3146-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song S.H., Oh T.R., Choi H.S., et al. High serum adiponectin as a biomarker of renal dysfunction: results from the KNOW-CKD study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5598. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62465-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamamoto M., Fujimoto Y., Hayashi S., Hashida S. A study of high-, middle- and low-molecular weight adiponectin in urine as a surrogate marker for early diabetic nephropathy using ultrasensitive immune complex transfer enzyme immunoassay. Ann Clin Biochem. 2018;55:525–534. doi: 10.1177/0004563217748681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bulum T., Vucic Lovrencic M., Tomic M., et al. Serum adipocytokines are associated with microalbuminuria in patients with type 1 diabetes and incipient chronic complications. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:496–499. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panduru N.M., Saraheimo M., Forsblom C., et al. Urinary adiponectin is an independent predictor of progression to end-stage renal disease in patients with type 1 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:883–890. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lierova A., Kasparova J., Filipova A., et al. Hyaluronic acid: known for almost a century, but still in vogue. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:838. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14040838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bukosza E.N., Kornauth C., Hummel K., et al. ECM characterization reveals a massive activation of acute phase response during FSGS. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2095. doi: 10.3390/ijms21062095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oh H., Park H.E., Song M.S., Kim H., Baek J.H. The therapeutic potential of anticoagulation in organ fibrosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.866746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trouw L.A., Nilsson S.C., Goncalves I., Landberg G., Blom A.M. C4b-binding protein binds to necrotic cells and DNA, limiting DNA release and inhibiting complement activation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1937–1948. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trouw L.A., Bengtsson A.A., Gelderman K.A., Dahlback B., Sturfelt G., Blom A.M., Blom A.M. C4b-binding protein and factor H compensate for the loss of membrane-bound complement inhibitors to protect apoptotic cells against excessive complement attack. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28540–28548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ricklin D., Hajishengallis G., Yang K., Lambris J.D. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ricklin D., Reis E.S., Lambris J.D. Complement in disease: a defence system turning offensive. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:383–401. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li X., Ding F., Zhang X., Li B., Ding J. The expression profile of complement components in podocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:471. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nastase M.V., Janicova A., Roedig H., Hsieh L.T., Wygrecka M., Schaefer L. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans in renal inflammation: two sides of the coin. J Histochem Cytochem. 2018;66:261–272. doi: 10.1369/0022155417738752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zou W., Wan J., Li M., et al. Small leucine rich proteoglycans in host immunity and renal diseases. J Cell Commun Signal. 2019;13:463–471. doi: 10.1007/s12079-018-0489-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schaefer L. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1200–1207. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang Y., Luo R., Cheng Y., et al. Leucine-rich alpha2-glycoprotein-1 upregulation in plasma and kidney of patients with lupus nephritis. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:122. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01782-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang X., Abraham S., McKenzie J.A.G., et al. LRG1 promotes angiogenesis by modulating endothelial TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2013;499:306–311. doi: 10.1038/nature12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haku S., Wakui H., Azushima K., et al. Early enhanced leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein-1 expression in glomerular endothelial cells of type 2 diabetic nephropathy model mice. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2817045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jemmerson R., Staskus K., Higgins L., Conklin K., Kelekar A. Intracellular leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein-1 competes with Apaf-1 for binding cytochrome c in protecting MCF-7 breast cancer cells from apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2021;26:71–82. doi: 10.1007/s10495-020-01647-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee H., Fujimoto M., Ohkawara T., et al. Leucine rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a potential urinary biomarker for renal tubular injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498:1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lueck A., Brown D., Kwiatkowski D.J. The actin-binding proteins adseverin and gelsolin are both highly expressed but differentially localized in kidney and intestine. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:3633–3643. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.24.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Feldt J., Schicht M., Garreis F., Welss J., Schneider U.W., Paulsen F. Structure, regulation and related diseases of the actin-binding protein gelsolin. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2019;20:e7. doi: 10.1017/erm.2018.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Piktel E., Levental I., Durnas B., Janmey P.A., Bucki R. Plasma gelsolin: indicator of inflammation and its potential as a diagnostic tool and therapeutic target. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2516. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Peddada N., Sagar A., Ashish G.R., Garg R. Plasma gelsolin: a general prognostic marker of health. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin Q., Mao J.H. Early prediction of acute kidney injury in children: known biomarkers but novel combination. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:617–620. doi: 10.1007/s12519-018-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lennon R., Randles M.J., Humphries M.J. The importance of podocyte adhesion for a healthy glomerulus. Front Endocrinol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00160. 5doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Labat-de-Hoz L., Alonso M.A. Formins in human disease. Cells. 2021;10:2554. doi: 10.3390/cells10102554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leavesley D.I., Kashyap A.S., Croll T., et al. Vitronectin--master controller or micromanager? IUBMB Life. 2013;65:807–818. doi: 10.1002/iub.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoon S., Gingras D., Bendayan M. Alterations of vitronectin and its receptor alpha (v) integrin in the rat renal glomerular wall during diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:1298–1306. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.29228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fu G., Du Y., Chu L., Zhang M. Discovery and verification of urinary peptides in type 2 diabetes mellitus with kidney injury. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2016;241:1186–1194. doi: 10.1177/1535370216629007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Morioka S., Makino H., Shikata K., Ota Z. Changes in plasma concentrations of vitronectin in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Acta Med Okayama. 1994;48:137–142. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hao P., Adav S.S., Gallart-Palau X., Sze S.K. Recent advances in mass spectrometric analysis of protein deamidation. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2017;36:677–692. doi: 10.1002/mas.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lorand L., Iismaa S.E. Transglutaminase diseases: from biochemistry to the bedside. FASEB J. 2019;33:3–12. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801544R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Anokhin B.A., Stribinskis V., Dean W.L., Maurer M.C. Activation of factor XIII is accompanied by a change in oligomerization state. FEBS Journal. 2017;284:3849–3861. doi: 10.1111/febs.14272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kalim S., Berg A.H., Karumanchi S.A., et al. Protein carbamylation and chronic kidney disease progression in the chronic renal insufficiency Cohort Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;37:139–147. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.