Abstract

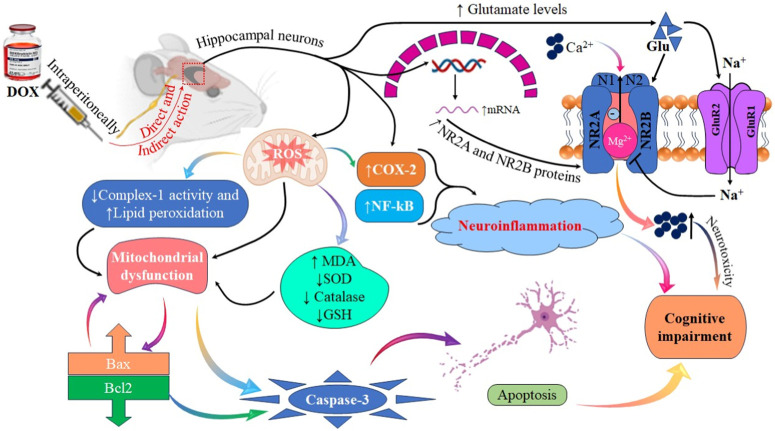

Introduction: The anticancer drug doxorubicin (DOX) is used for various malignancies. However, it also causes cognitive impairment in cancer survivors. In order to determine the mechanisms underlying the acute effects of DOX, we assessed the mRNA and protein expression of glutamate receptors and proteins involved in cognitive function and apoptosis.

Methods: Fear-conditioning memory tests were performed in rats after a single intraperitoneal injection of DOX (25 mg/kg) to evaluate short-term memory function. Rat brain samples were collected, and GluA1 mRNA and protein expression; NR2A and NR2B mRNA expression; and COX-2, NF-kB, TNF-α, and MDA, Bax, and caspase-3 levels were assessed via reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

Results: We observed a decreased number of entries in Y-maze, decreased exploration time to the novel object in the novel object recognition (NOR), and decreased freezing time in the fear-conditioning memory tests in DOX-treated rats relative to those in control rats, demonstrating cognitive impairment. GluA1, NR2B, and NR2A expression and MDA, NF-κB, Bax, COX-2, TNF-α, and caspase-3 levels in the brain were significantly elevated in DOX-treated rats.

Conclusion: DOX induced cognitive impairment in the rats via neuronal toxicity by upregulating AMPAR and NMDAR expression and increasing neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in the brain.

Keywords: AMPAR, Bax, COX-2, cognitive impairment, doxorubicin, NMDAR, NF-κB, TNF-α

1 Introduction

The anthracycline doxorubicin (DOX) is widely applied in the therapy of several cancers, including breast and prostate cancers (Thorn et al., 2011). DOX primarily reduces DNA synthesis by inhibiting topoisomerase II, thereby enhancing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and disrupting mitochondrial function (Alharbi et al., 2020). Although DOX is an effective anticancer agent, it is associated with several side effects, including cardiotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity (Zhao and Zhang, 2017; Song et al., 2019; Afsar et al., 2020; Alharbi et al., 2020). Recent studies have linked DOX to chemo brain (Alharbi et al., 2020). However, only few studies have focused on the underlying mechanisms and etiology of chemo brain (Alhowail et al., 2019a; Alhowail et al., 2019b; Alharbi et al., 2020). DOX is ionized and hence does not easily cross the intact blood–brain barrier (Bredlau et al., 2018). Therefore, it can cause cognitive impairment by directly affecting the central nervous system and through indirect mechanisms, such as excessive ROS production, resulting in increased lipid peroxidation, impaired synaptic plasticity, and mitochondrial dysfunction (Alhowail et al., 2019a). Although DOX impairs hippocampal-dependent tasks and cognitive function, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

Glutamate is a prevalent excitatory neurotransmitter and is also neurochemically synthesized in the brain (Zhou and Danbolt, 2014; Lieu et al., 2020). Glutamate receptors are classified as either ionotropic or metabotropic (Crupi et al., 2019). N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) and -amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate receptors (AMPARs) are two examples of ionotropic receptors, which play vital roles in synaptic and cognitive functions (Traynelis et al., 2010; Bhattacharya et al., 2017). Upon neuronal stimulation, the presynaptic terminal releases glutamate into the synaptic cleft, which binds to AMPARs and NMDARs and causes conformational changes (Alhowail et al., 2022). AMPARs elicit an influx of Na+, depolarizing the membranes of postsynaptic neurons (Zanetti et al., 2021; Alhowail et al., 2022). At resting potential (−65 mV), NMDARs are closed by Mg2+ (Kampa et al., 2004). Postsynaptic membrane depolarization by AMPARs removes this blockade, permitting Ca2+ influx, which is essential for downstream memory formation (Luscher and Malenka, 2012). AMPARs comprise four subunits (GluA1–4), which are differentially expressed (Bhattacharya et al., 2017; Polli and Kohlmeier, 2022). In the adult brain, GluA1 is permeable to Ca2+; however, GluA2 is not permeable to Ca2+ because of the presence of arginine in its receptor, which blocks Ca2+ permeability through AMPARs (Wright and Vissel, 2012; Livingstone et al., 2021). Therefore, the presence of more GluA1 in the AMPAR structure allows Ca2+ influx through the cell membrane, causing neuronal toxicity (Qu et al., 2020; Livingstone et al., 2021). In addition, NMDARs comprise the NR1, NR2A, NR2B, and NR2C subunits, which are vital to synaptic plasticity and cognitive function (Brothwell et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 2023). Therefore, alterations in the expression and activity of these receptors directly affect general brain function by reducing or increasing downstream signaling, thereby causing cognitive impairment (Yang et al., 2022).

The transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) controls several genes related to cellular development, survival, apoptosis, and stress response as well as inflammation development and progression (Park and Hong, 2016). Activation of NF-κB can stimulate the transcription of TNF-α genes, which activate tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), promoting proinflammatory cytokine production and leading to neuroinflammation, upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression, and apoptosis (Poligone and Baldwin, 2001; Li et al., 2005). Furthermore, the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) is a mitochondrial membrane protein that regulates membrane permeability (Singh et al., 2015; Hsieh et al., 2016). At the physiological cellular level, Bax expression and function regulate the mitochondrial membrane (Shamas-Din et al., 2013). However, under oxidative stress, the increase in Bax expression in the outer mitochondrial membrane induces the formation of pores, which cause the release of cytochrome C, activating the apoptosome and caspase-3 cascade, resulting in apoptosis (Gao and Wang, 2009; Naseri et al., 2015). Moreover, increased malondialdehyde (MDA), ROS production, and lipid peroxidation characterize oxidative stress, resulting in damage to cellular function, and stimulate apoptosis (Su et al., 2019). The susceptibility of the brain to oxidative stress and its effects on metabolism and synaptic activities have been reported in Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (Pimentel et al., 2012). In addition, increasing evidence suggests that DOX can induce cognitive decline, reduced long-term potentiation (LTP), and synaptic dysfunction (Alhowail et al., 2019a).

Decreased expression and activity of AMPARs and NMDARs can impair cognitive function (Li and Tsien, 2009; Alhowail, 2021). In contrast, upregulated AMPAR and NMDAR expression increases Ca2+ influx, causing neuronal injury, toxicity, and apoptosis, ultimately leading to cognitive dysfunction (Newcomer et al., 2022). Therefore, cellular Ca2+ balance is essential for memory formation (Ureshino et al., 2019). Despite the high incidence of chemo brain in breast cancer survivors and widespread use of DOX in breast cancer therapy, little is known about the effects of DOX on cognitive function in female rats. Thus, in this research, it is investigated DOX-induced cognitive impairment in female rats. The goal of this investigation was to determine the acute effects of DOX on cognitive function, particularly its impact on the expression of AMPAR and NMDAR subunits; inflammatory and oxidative stress mediators, such as NF-κB, COX-2, MDA, and TNF-α; and markers of apoptosis, such as caspase-3 and Bax.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and drugs

DOX was purchased from EBEWE Pharma GmbH Nfg KG (Attersee, Austria).

2.2 Animal treatments

Twenty female albino rats, each aged 3 months, were housed individually in small cages. These cages were subjected to a light/dark cycle of 12 h per day, with the lights being switched on precisely at 7:30 a.m. Throughout the duration of the study, the rats were provided with unrestricted access to both water and food. The experimental subjects, namely, the rats, were divided into two distinct groups for the purpose of this study. The first group, referred to as the control group, consisted of ten rats. Similarly, the second group, known as the DOX group, also comprised ten rats. The DOX group was administered intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 25 mg/kg DOX, while the control group was subjected to a solitary i. p. injection of saline.

2.3 Y-maze

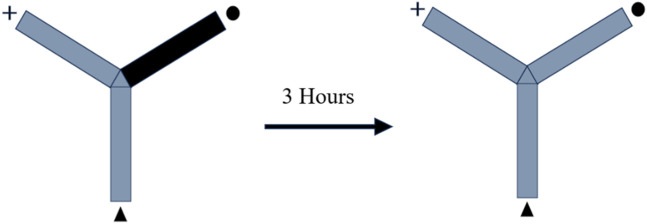

The Y-shaped maze has three wooden arms that measure 50 cm, 10 cm, and 20 cm, respectively, and they are arranged at an angle of 120°. In order to evaluate the rats’ memory, the novel arm of the Y-maze was purposefully made inaccessible. In this particular study, each arm was categorized as either a “starter,” “familiar,” or “novel.” One rat was put into the starting arm, and during each training session, it had free access to the familiar arm for a period of 10 minutes. The test was redone after 3 hours with no restrictions placed on maze exploration and all arms open. For the second time during the experiment, the animal was positioned in the starter arm, and its behavior during the subsequent 3 minutes was monitored to determine whether it preferred the unfamiliar or the familiar conditions. Within the confines of the maze, light was spread out uniformly. It was determined by analyzing videos of the test sessions how long rats remained in the novel arm as well as how many times they entered the arm. It was determined that the animal had entered the arm if all four paws were seen entering the arm (Figure 1) (Alsaud et al., 2023).

FIGURE 1.

Illustration depicting the schematic representation of the experimental design.

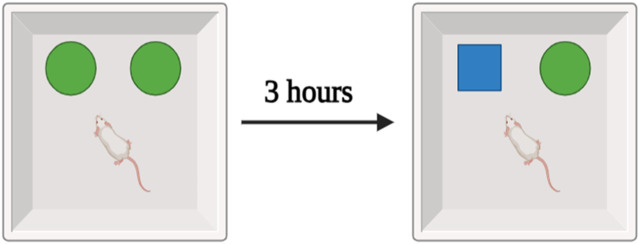

2.4 Novel object recognition test

In the experiment, a wooden box measuring 40 cm on a side, 40 cm on a side, and 40 cm on a side was used to contain two items: a set of familiar black cans, and an unfamiliar white teacup. The rat spent 10 minutes in the middle of the maze investigating a group of similar black cans. The training period lasted for 3 hours, and then the test session consisted of exposing the rat to a new object (a teacup) for 3 minutes. During the testing session, video cameras recorded the amount of time spent by each animal investigating a novel object. The collected data were then subjected to statistical analysis (Figure 2) (Alsaud et al., 2023).

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of the experimental design.

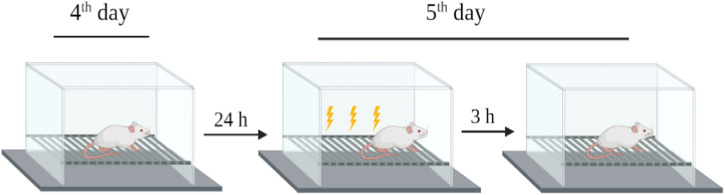

2.5 Fear-conditioning memory tests

The rats were placed in a standard rat operating chamber in a sound isolation cubicle with an electrified grid floor to deliver shocks to their feet (hereafter referred to as “the context”). A conditioned freezing protocol was used to train the rats. On day 4 after treatment, the rats were exposed to the context for 30 min to habituate them to the chamber without foot shock. On day 5 after treatment, the rats were returned to the chamber for 180 s and received multiple electrical foot shocks in different contexts. After 3 h (day 5), the rats were restored to baseline for 180 s without electrical foot shocks. Freezing behavior (no movements except respiration-related movements) was used to evaluate fear memory function by analyzing the changes in freezing times between the treated and control groups (Figure 3) (Alhowail et al., 2022).

FIGURE 3.

Schematic of the experimental design for fear-conditioning memory test.

2.6 Preparation of brain samples

The rodents were humanely euthanized via CO2 inhalation, followed by the decapitation of their heads prior to the extraction of their brains. Following the removal of blood from the brains utilizing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the subsequent step involved the extraction of the brain. In order to facilitate the extraction of proteins from neurons, we utilized a Qsonica homogenizer (operating at a frequency of 30 Hz) manufactured by the esteemed company located in Newtown, CT, United States of America. Additionally, we employed a lysis buffer (specifically, N-PER) that was procured from the reputable supplier Thermo Scientific, headquartered in Madison, WI, United States of America. The specimens were subjected to centrifugation at a temperature of 4 °C for a duration of 10 min at a force of 12,000 times the acceleration due to gravity (12,000 × g). Following centrifugation, the resulting liquid portion above the sediment, known as the supernatant, was carefully transferred to newly prepared Eppendorf tubes. Prior to subjecting the samples to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay was conducted in order to ascertain the total protein content (Alhowail et al., 2019a).

2.7 Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

The RNA was isolated from brain samples obtained from animals treated with DOX and control animals utilizing the TRIzol reagent, a product manufactured by Sigma-Aldrich located in St. Louis, MO, United States of America. The residual genomic DNA was subsequently isolated from the total RNA using RNase-free DNase (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA, United States of America). The RNA content and absorbance were calculated utilizing a NanoDrop spectrophotometer manufactured by Thermo Fisher Scientific, located in Loughborough, United Kingdom. The synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) was performed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States of America) on a total RNA sample of 500 ng. The cDNA samples were subsequently amplified using Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Shanghai, China). SYBR Green, a fluorescent dye commonly employed in molecular biology research, specifically in the realm of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), was utilized in this study. The RT-PCR procedure was conducted on an iCycler iQ5 system, a thermocycler manufactured by Bio-Rad, a reputable company based in Hercules, California, United States. The synthesis of primers was performed utilizing a proprietary software developed by Integrated DNA Technologies. The RT-PCR experiment was performed utilizing Bio-Rad’s Advanced SYBR Green Supermix with the specified parameters: an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 amplification cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s, and annealing/extension at 57°C for 30 s. Duplicate samples were meticulously prepared, and a rigorous triad of tests was conducted. After the completion of plate-setting, the acquired data were subjected to automated processing utilizing the AiraMx software for the purpose of comparative quantification. The gene expression levels were standardized relative to the reference gene GAPDH, which is commonly used as a housekeeping gene. The quantification of mRNA expression alterations was determined through the estimation of transcript abundance per gene in relation to the reference gene GAPDH (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Primers utilized in the study.

| Gene | Sequence (5′–3′) | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| GluA1 | Forward: GCCAGATCGTGAAGCTAGAAA | 80 |

| GluA1 | Reverse: CTCCGCTCTCCTTGAACTTATT | |

| NR2A | Forward: GGAGGAGGTTGGGTCATTTAT | 86 |

| NR2A | Reverse: AGTAGGCACTTGGGACTTTAC | |

| NR2B | Forward: GAGGAACCAGGCTACATCAAA | 83 |

| NR2B | Reverse: GGTCACCAGGTAAAGGTCATAG | |

| GAPDH | Forward: ACTCCCATTCTTCCACCTTTG | 104 |

| GAPDH | Reverse: CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCATATT |

2.8 ELISA

Brain samples from the rats in the DOX and control groups that were treated with N-PER and used for BCA were subjected to ELISA for GluA1, Bax, and caspase-3 levels using commercially available kits (MyBioSource Company, San Diego, CA, United States of America) according to the protocols of the manufacturers. The absorbance at 450 nm was read using a BIO-TEK Absorbance Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, United States of America). The data were then subjected to statistical analysis.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Data from DOX-treated and control rats were compared utilizing a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test in GraphPad Prism 10.0.0.153 (GraphPad Prism Software, San Diego, California, United States of America). When p was smaller than 0.05, a difference was found using every parametric statistic. Both the mean and the standard error of the mean (SEM) are shown for these results.

3 Results

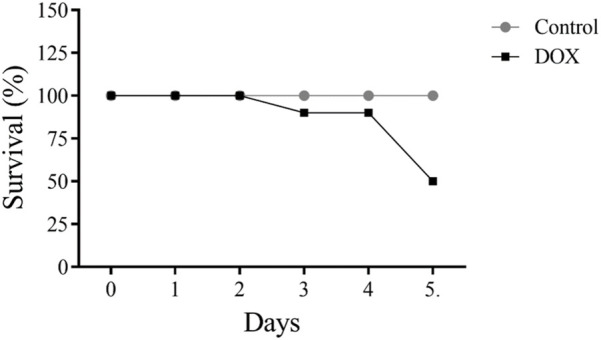

3.1 DOX increases the mortality rate of rats

5 of 10 (50%) rats administered DOX died after 5 days of therapy (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of acute doxorubicin (DOX) treatment on rat survival. Only 50% of rats in the DOX group survived after 5 days of treatment.

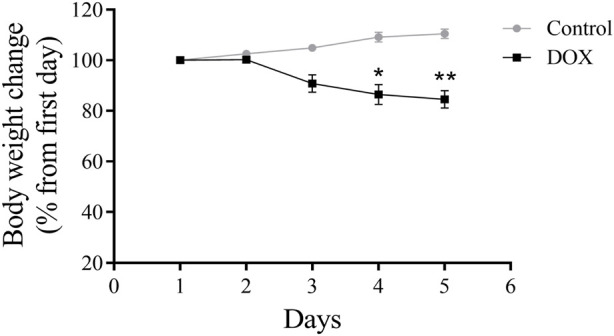

3.2 DOX decreases body weight of rats

The body weight of DOX-treated rats was substantially lower than that of control rats (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of DOX on rat body weight. The study lasted for 5 days. The DOX-treated rats had significantly reduced body weights. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

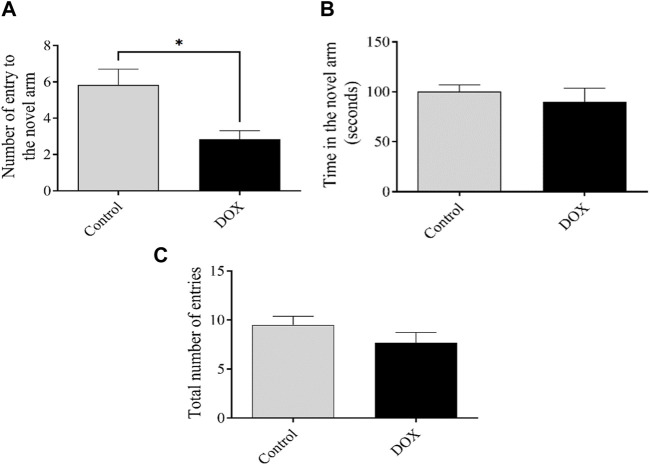

3.3 DOX impair cognitive function in the Y-maze test

The number of entries and time spent in the novel arm reflect the ability of an animal to discover a new unexposed arm. The quantity of rat entries within the DOX group exhibited a statistically notable drop (p < 0.05) when related to the control group’s rat entries. (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

The impact of DOX on rat behavior in the Y-maze test shall be elucidated. (A and B) The impact of DOX administration on the quantity of entries and duration of stay in the novel arm. (C) The cumulative count of participants across all treatment groups. The data presented in this study is represented by bars, which indicate the mean value plus or minus the standard error of the mean (SEM). (*p < 0.05).

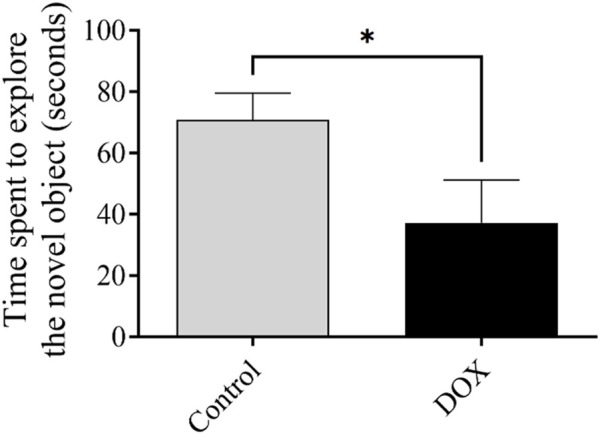

3.4 Effect of DOX on rat behavior in the novel object recognition test

The exploration time reflects the ability of an animal to recall a previously exposed object. The exploration time of rats in the DOX group was significantly lower (p < 0.05) that of the control rats (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

The impact of DOX on rat behavior within the context of the novel object recognition test. The impact of DOX administration on the duration dedicated to the investigation of the novel object. The data is represented by bars, which indicate the mean value plus or minus the standard error of the mean (SEM) (*p < 0.05).

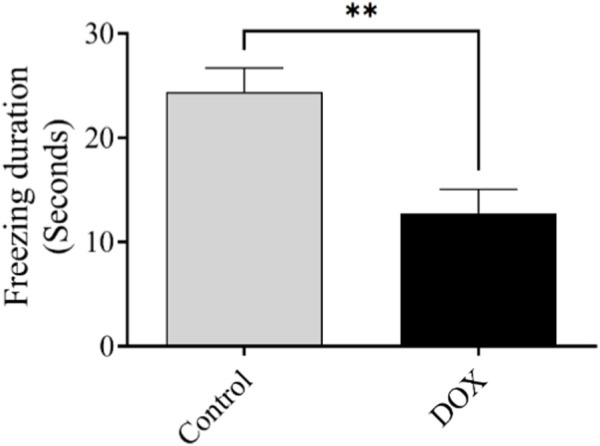

3.5 Effect of DOX on rat behavior in the fear-conditioning memory test

The freezing time reflects the ability of an animal to recall a previously exposed context. The freezing time of rats in the DOX group was notably lower (p < 0.01) than that of the control rats (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of DOX on rat behavior in the fear-conditioning memory test. Effects of DOX treatment on freezing time. Bars indicate the mean ± SEM (**p < 0.01).

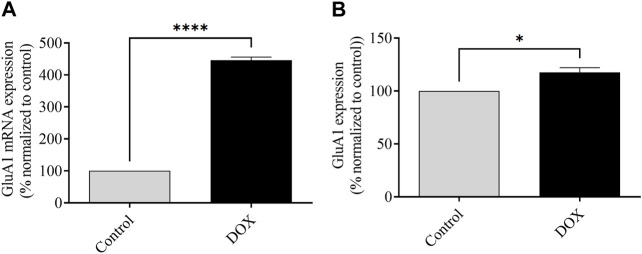

3.6 DOX therapy elevates mRNA and protein expression of GluA1 of AMPARs

The assessment of mRNA expression pertaining to GluA1-containing AMPARs was conducted subsequent to a 5-day administration of DOX treatment. As depicted in Figure 6, the rats subjected to DOX treatment demonstrated a notable elevation in the levels of GluA1 mRNA expression in comparison to the levels observed in the control rats.

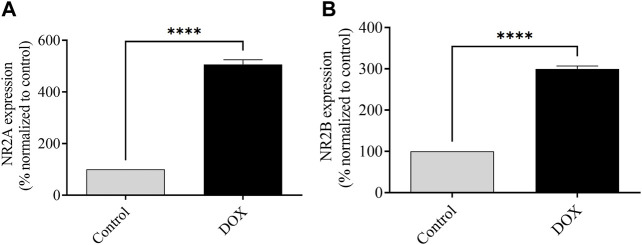

3.7 DOX upregulates the mRNA expression of NMDAR subunits NR2A and NR2B

The levels of NR2A and NR2B mRNA expression were assessed 5 days after DOX administration. The DOX-treated rats exhibited a significant elevation of NR2A and NR2B mRNA expression compared to those in control rats, which indicated the potential toxic effects of DOX (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

The impact of DOX on the mRNA expression of NR2A and NR2B, in comparison to the levels observed in control rats, is being evaluated. The expression of NR2A mRNA was observed to be significantly elevated in the group treated with DOX in comparison to the control group. The rats that received DOX treatment displayed an increase in the expression of NR2B mRNA, similar to the levels observed in the control rats. The utilization of bars in this context indicates the representation of the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (SEM) (****p < 0.0001).

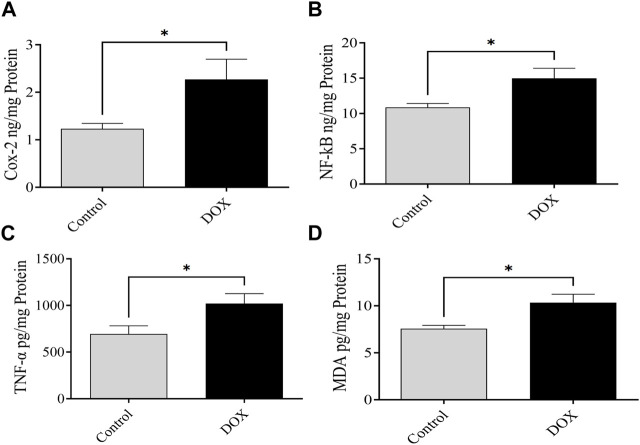

3.8 DOX upregulates NF-κB, MDA, COX-2, and TNF-α expression

The expression levels of NF-κB, MDA, COX-2, and TNF-α were assessed 5 days following DOX administration. The brain of DOX-treated rats demonstrated significantly increased levels of NF-κB, COX-2, MDA, and TNF-α compared with that of the controls (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Effects of DOX on the expression levels of NF-κB, COX-2, MDA, and TNF-α in the brain. (A–D) DOX-treated rats showed significantly higher COX-2 (A), NF-κB (B), TNF-α (C), and MDA (D) expression than the controls. Bars symbolize the mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05).

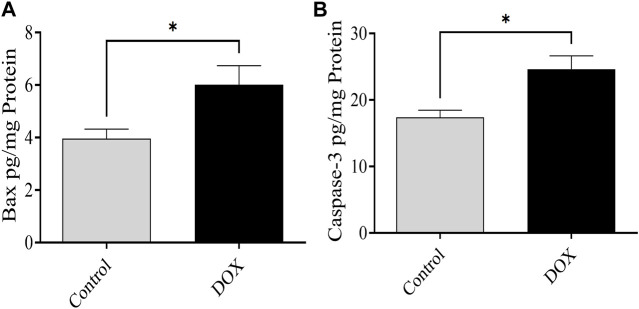

3.9 DOX upregulates Bax and caspase-3 expression

The expression of Bax and caspase-3 was evaluated 5 days after DOX therapy. Rats in the DOX group exhibited a prominent elevation in the levels of caspase-3 and Bax in the brain compared with the controls (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Effects of DOX on caspase-3 and Bax levels in the brain. (A and B) The DOX-treated group showed significantly higher Bax (A) and caspase-3 (B) expression levels than the control group. Bars indicate mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05).

4 Discussion

In this study, we observed the impact of DOX on glutamatergic system-induced neuronal toxicity and cognitive impairment in a rat model. The results revealed that DOX caused neurotoxicity via overactivation of the glutamatergic system, thereby inducing apoptosis. DOX administration also significantly reduced body weight, accompanied by a decrease in spatial memory, as evidenced by a reduction in the number of entries in the Y-maze. Additionally, DOX administration resulted in a decrease in exploration time in the NOR test, a decline in freezing time in the fear-conditioning memory test, significantly elevated levels of the mRNA/protein expression of the glutamate subunit of AMPARs containing GluA1, and elevated mRNA expression levels of the glutamate subunit of NMDARs, which together resulted in neurotoxicity and memory impairment. Previous studies have shown that chronic DOX treatment causes cognitive impairment. One proposed mechanism involves reduced hippocampal neurogenesis (Kitamura et al., 2015; Alharbi et al., 2020; Usmani et al., 2023). The Y-maze and novel object recognition tests, in addition to elevated plus maze tests, in our previous research, have also shown that chronic DOX treatment impairs memory function (Alharbi et al., 2020; Alsaud et al., 2023). In this study, we investigated acute DOX treatment by evaluating spatial memory impairment using the Y-maze and NOR tests and other methods of memory impairment by assessing fear conditioning memory, which functions through a distinct pathway (amygdala-dependent learning memory), and the involvement of AMPARs and NMDARs in cognitive impairment as well as neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.

Alterations in AMPA and NMDA receptors can cause changes in neuronal function, which in turn alters the function of the central nervous system and can lead to cognitive impairment (Li and Tsien, 2009; Alhowail, 2021). These results support the hypothesis that DOX induces cognitive impairment in patients administered DOX. The GluA1 subunit protein and mRNA expression was upregulated in the brains of DOX-treated rats, which caused overactivation of neurons, increased Ca2+ influx, and increased Ca2+ concentration, leading to neuronal toxicity. Furthermore, our latest research involving the hippocampus of nude mice has uncovered the detrimental effects of chronic (Figure 12) DOX treatment on cognitive function. It was observed that this treatment led to a decrease in the presence of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPA receptors, which are crucial for proper brain function (Alhowail et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the evaluation of the current study, which utilized an acute dose of DOX, demonstrated a noteworthy rise in the presence of the GluA1 subunit within the AMPA receptor. Thus, it is speculated that the variation in results may be attributed to the utilization of the entire brain for protein expression assessment. Furthermore, the initiation of DOX treatment leads to an increase in GluA1, which in turn triggers apoptosis. Nevertheless, extended periods of treatment may lead to neuronal degeneration.

FIGURE 12.

Effects of DOX on GluA1-containing AMPAR expression. (A) Effects of DOX on mRNA expression of the GluA1 subunit of AMPARs relative to that in control rats. (B) Effects of DOX on AMPAR GluA1 subunit protein expression relative to that in control rats. Bars indicate mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001).

In addition, NMDARs play a vital role to synaptic plasticity and cognitive function (Brothwell et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 2023). In cases of prenatal nicotine or alcohol exposure, NMDAR expression is reduced, resulting in memory deficits and impaired LTP (Alhowail et al., 2021; Alhowail, 2022; Polli and Kohlmeier, 2022). Similarly, blocking NMDAR expression reduces LTP induction and results in memory impairment (Yang et al., 2018). In contrast, NMDAR overactivation can increase Ca2+ entry into neurons, leading to neuronal toxicity and initiation of apoptosis (Dong et al., 2009; Ndountse and Chan, 2009). These results agree with a recent finding that post-treatment with DOX can elevate glutamate levels owing to decreased clearance in the frontal cortex of rodent models (Thomas et al., 2017), which increases glutamate receptor expression.

DOX administration leads to enhanced expression of proinflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, in the brain (Keeney et al., 2018). NF-κB activates the TNF-α gene to enhance the transcription and translation of proteins (Coelho-Santos et al., 2015). The proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α may cross the blood–brain barrier and result in central inflammation in the brain (Huang et al., 2020). The results of the current study revealed that DOX causes neurotoxicity by enhancing the production of proinflammatory mediators TNF-α and COX-2 in the brain, leading to neuroinflammation. These results were evident from the significantly elevated levels of TNF-α, NF-κB, and COX-2 in the brain samples from the DOX-treated rats compared to those in the controls. Furthermore, the DOX-induced elevated neuroinflammation was linked to oxidative stress due to increased levels of MDA in the brain, causing cognitive impairment.

Furthermore, it is imperative to note that the adequate expression and optimal functioning of Bax are indispensable for maintaining the regular cellular processes and promoting proper cellular development (Hardwick and Soane, 2013). Bax, an indispensable participant in the process of apoptosis, assumes a crucial function in the activation of caspase signaling through the release of cytochrome C from the mitochondria (Wang and Youle, 2009). The upregulation of Bax expression elicits the release of cytochrome C, thereby instigating the process of apoptosis through the activation of caspase-3 (An et al., 2004; Mizuta et al., 2007). Moreover, the pathogenesis of various disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, can lead to the upregulation of Bax and caspase-3 expression, ultimately resulting in neurodegeneration (Long et al., 2021; Wolfrum et al., 2022). In a similar vein, chemotherapeutic agents, such as DOX, have been observed to enhance the expression of Bax and caspase-3, leading to the induction of apoptosis (Sharifi et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2019). The results of the present study revealed notable differences in the expression levels of caspase-3 and Bax between the group treated with DOX and the control group. Specifically, it was observed that these levels exhibited an increase subsequent to DOX therapy. Hence, the administration of acute DOX therapy has the potential to enhance the process of apoptosis through the upregulation of Bax and caspase-3 expression, ultimately leading to the initiation of apoptosis. Additional investigations pertaining to Bax and caspase-3, along with their associated signaling proteins situated both upstream and downstream, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase and the generation of reactive oxygen species, are imperative in order to gain comprehensive insights into the modifications induced by DOX in the expression of Bax and caspase-3.

This study is subject to specific strengths and limitations. To the utmost extent of our comprehension, this investigation represents the primary endeavor to combine the impact of DOX on the intricate interplay of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and the excessive stimulation of the glutamatergic system. The animal subjects utilized in this investigation were of identical strain and age, and all experimental procedures were carried out concurrently across the study cohorts to mitigate the influence of confounding variables. Additionally, the utilization of cancer-free rats was employed to assess the direct impact of DOX treatment, thereby minimizing any potential confounding effects originating from the presence of cancer. Moreover, it should be noted that one aspect of concern relates to the administration of a solitary dose to the animal subjects, consequently resulting in a partial replication of the dosing regimen observed in human individuals. However, the selection of this specific dosage was made with the intention of investigating its impact on survival rates and the underlying mechanisms of cognitive impairment. An additional limitation concerns the exclusive evaluation of mRNA levels pertaining to NMDARs subunits NR2A and NR2B, without simultaneous examination of protein expression in the brain. However, it is important to note that the aforementioned situation can be ascribed to the inherent limitations imposed by the existing laboratory infrastructure.

In conclusion, our findings supported the hypothesis that DOX induces cognitive impairment by altering glutamate receptor expression, leading to neurotoxicity. Furthermore, the molecular mechanism underlying cognitive impairment was investigated, and the results suggested that DOX increased the expression of the GluA1 subunit of AMPARs and NR2A and NR2B subunits of NMDARs. This was associated with neuronal toxicity via activation of inflammatory and oxidative stress mediators, such as NF-κB, COX-2, MDA, and TNF-α, and pro-apoptotic protein (Bax, and caspase-3) signaling, which resulted in apoptosis and decreased cognitive performance. Additional research is required to examine the expression and function of AMPAR and NMDAR subunits following acute DOX exposure. A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying chemotherapy can help elucidate the pharmacological management required to mitigate the cognitive impairment caused by chemotherapy (Figure 13).

FIGURE 13.

Illustrative figure demonstrating the effects and mechanism of DOX in causing cognitive impairment and neurotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to MA and Ibtesam Almami for their assistance in performing RT-PCR.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at Qassim University and the Deanship for Scientific Research approved the study (approval number 23-33-22). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AA and MA the authors conceptualized the study, designed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, supervised the study, and provided final approval for submission equally. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Afsar T., Razak S., Almajwal A., Al-Disi D. (2020). Doxorubicin-induced alterations in kidney functioning, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and renal tissue morphology; Improvement by Acacia hydaspica tannin-rich ethyl acetate fraction. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 2251–2260. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi I., Alharbi H., Almogbel Y., Alalwan A., Alhowail A. (2020). Effect of metformin on doxorubicin-induced memory dysfunction. Brain Sci. 10, 152. 10.3390/brainsci10030152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhowail A. (2021). Molecular insights into the benefits of nicotine on memory and cognition (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 23, 398. 10.3892/mmr.2021.12037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhowail A. (2022). Mechanisms underlying cognitive impairment induced by prenatal alcohol exposure. Brain Sci. 12, 1667. 10.3390/brainsci12121667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhowail A. H., Almogbel Y. S., Abdellatif A. A. H., Aldubayan M. A., Chigurupati S., Nemala R. A. (2022). Effects of CMF and MET on glutamate and dopamine levels in the brain, and their impact on cognitive function. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 2353–2362. 10.26355/eurrev_202204_28465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhowail A. H., Bloemer J., Majrashi M., Pinky P. D., Bhattacharya S., Yongli Z., et al. (2019a). Doxorubicin-induced neurotoxicity is associated with acute alterations in synaptic plasticity, apoptosis, and lipid peroxidation. Toxicol. Mech. methods 29, 457–466. 10.1080/15376516.2019.1600086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhowail A. H., Chigurupati S., Sajid S., Mani V. (2019b). Ameliorative effect of metformin on cyclophosphamide-induced memory impairment in mice. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 9660–9666. 10.26355/eurrev_201911_19460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhowail A. H., Pinky P. D., Eggert M., Bloemer J., Woodie L. N., Buabeid M. A., et al. (2021). Doxorubicin induces dysregulation of AMPA receptor and impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity leading to learning and memory deficits. Heliyon 7, e07456. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaud M. M., Alhowail A. H., Aldubayan M. A., Almami I. S. (2023). The ameliorative effect of pioglitazone against neuroinflammation caused by doxorubicin in rats. Molecules 28, 4775. 10.3390/molecules28124775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J., Chen Y., Huang Z. (2004). Critical upstream signals of cytochrome c release induced by a novel bcl-2 inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19133–19140. 10.1074/jbc.M400295200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S., Kimble W., Buabeid M., Bhattacharya D., Bloemer J., Alhowail A., et al. (2017). Altered AMPA receptor expression plays an important role in inducing bidirectional synaptic plasticity during contextual fear memory reconsolidation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 139, 98–108. 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredlau A. L., Motamarry A., Chen C., McCrackin M. A., Helke K., Armeson K. E., et al. (2018). Localized delivery of therapeutic doxorubicin dose across the canine blood-brain barrier with hyperthermia and temperature sensitive liposomes. Drug Deliv. 25, 973–984. 10.1080/10717544.2018.1461280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothwell S. L. C., Barber J. L., Monaghan D. T., Jane D. E., Gibb A. J., Jones S. (2008). NR2B- and NR2D-containing synaptic NMDA receptors in developing rat substantia nigra pars compacta dopaminergic neurones. J. Physiology 586, 739–750. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho-Santos V., Leitão R. A., Cardoso F. L., Palmela I., Rito M., Barbosa M., et al. (2015). The TNF-α/NF-κB signaling pathway has a key role in methamphetamine-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabolism 35, 1260–1271. 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crupi R., Impellizzeri D., Cuzzocrea S. (2019). Role of metabotropic glutamate receptors in neurological disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12, 20. 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X.-x., Wang Y., Qin Z.-h. (2009). Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30, 379–387. 10.1038/aps.2009.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C., Wang A.-Y. (2009). Significance of increased apoptosis and Bax expression in human small intestinal adenocarcinoma. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 57, 1139–1148. 10.1369/jhc.2009.954446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick J. M., Soane L. (2013). Multiple functions of BCL-2 family proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a008722. 10.1101/cshperspect.a008722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y.-H., Wang Q., Zhang L., Yuan X., Ou Y., Zhu X., et al. (2016). The relationship between the bcl-2/bax proteins and the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway in the differentiation of adipose-derived stromal cells into neurons. Plos One 11, e0163327. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Hussain B., Chang J. (2020). Peripheral inflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption: effects and mechanisms. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 27, 36–47. 10.1111/cns.13569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampa B. M., Clements J., Jonas P., Stuart G. J. (2004). Kinetics of Mg2+ unblock of NMDA receptors: implications for spike-timing dependent synaptic plasticity. J. Physiol. 556, 337–345. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney J. T. R., Ren X., Warrier G., Noel T., Powell D. K., Brelsfoard J. M., et al. (2018). Doxorubicin-induced elevated oxidative stress and neurochemical alterations in brain and cognitive decline: protection by MESNA and insights into mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment (“chemobrain”). Oncotarget 9, 30324–30339. 10.18632/oncotarget.25718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura Y., Hattori S., Yoneda S., Watanabe S., Kanemoto E., Sugimoto M., et al. (2015). Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide treatment produces anxiety-like behavior and spatial cognition impairment in rats: possible involvement of hippocampal neurogenesis via brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cyclin D1 regulation. Behav. Brain Res. 292, 184–193. 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Tsien J. Z. (2009). Memory and the NMDA receptors. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 302–303. 10.1056/NEJMcibr0902052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. H., Jang J. H., Surh Y. J. (2005). Nitric oxide induces apoptosis via AP-1-driven upregulation of COX-2 in rat pheochromocytoma cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 39, 890–899. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu E. L., Nguyen T., Rhyne S., Kim J. (2020). Amino acids in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 15–30. 10.1038/s12276-020-0375-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone R. W., Elder M. K., Singh A., Westlake C. M., Tate W. P., Abraham W. C., et al. (2021). Secreted amyloid precursor protein-alpha enhances LTP through the synthesis and trafficking of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 14, 660208. 10.3389/fnmol.2021.660208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H.-Z., Cheng Y., Zhou Z.-W., Luo H.-Y., Wen D.-D., Gao L.-C. (2021). PI3K/AKT signal pathway: a target of natural products in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 648636. 10.3389/fphar.2021.648636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C., Malenka R. C. (2012). NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTP/LTD). Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a005710. 10.1101/cshperspect.a005710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuta T., Shimizu S., Matsuoka Y., Nakagawa T., Tsujimoto Y. (2007). A bax/bak-independent mechanism of cytochrome c release. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16623–16630. 10.1074/jbc.M611060200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naseri M. H., Mahdavi M., Davoodi J., Tackallou S. H., Goudarzvand M., Neishabouri S. H. (2015). Up regulation of Bax and down regulation of Bcl2 during 3-NC mediated apoptosis in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 15, 55. 10.1186/s12935-015-0204-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndountse L. T., Chan H. M. (2009). Role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in polychlorinated biphenyl mediated neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 184, 50–55. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer J. W., Farber N. B., Olney J. W. (2022). NMDA receptor function, memory, and brain aging. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2, 219–232. 10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.3/jnewcomer [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. H., Hong J. T. (2016). Roles of NF-κB in cancer and inflammatory diseases and their therapeutic approaches. Cells 5, 15. 10.3390/cells5020015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel C., Batista-Nascimento L., Rodrigues-Pousada C., Menezes R. A. (2012). Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: insights from the YeastSaccharomyces cerevisiae. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 132146–132149. 10.1155/2012/132146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poligone B., Baldwin A. S. (2001). Positive and negative regulation of NF-kappaB by COX-2: roles of different prostaglandins. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38658–38664. 10.1074/jbc.M106599200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polli F. S., Kohlmeier K. A. (2022). Prenatal nicotine alters development of the laterodorsal tegmentum: possible role for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and drug dependence. World J. Psychiatry 12, 212–235. 10.5498/wjp.v12.i2.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu W., Yuan B., Liu J., Liu Q., Zhang X., Cui R., et al. (2020). Emerging role of AMPA receptor subunit GluA1 in synaptic plasticity: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Cell Prolif. 54, e12959. 10.1111/cpr.12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamas-Din A., Kale J., Leber B., Andrews D. W. (2013). Mechanisms of action of bcl-2 family proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a008714. 10.1101/cshperspect.a008714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi S., Barar J., Hejazi M. S., Samadi N. (2015). Doxorubicin changes Bax/Bcl-xL ratio, caspase-8 and 9 in breast cancer cells. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 5, 351–359. 10.15171/apb.2015.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh L., Pushker N., Saini N., Sen S., Sharma A., Bakhshi S., et al. (2015). Expression of pro-apoptotic Bax and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins in human retinoblastoma. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 43, 259–267. 10.1111/ceo.12397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Letai A., Sarosiek K. (2019). Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: the balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 175–193. 10.1038/s41580-018-0089-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Chu L., Liang H., Chen J., Liang J., Huang Z., et al. (2019). Protective effects of dioscin against doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity via regulation of sirt1/FOXO1/NF-κb signal. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1030. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L.-J., Zhang J.-H., Gomez H., Murugan R., Hong X., Xu D., et al. (2019). Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 5080843–5080913. 10.1155/2019/5080843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., Nakamoto C., Watanabe-Iida I., Watanabe M., Takeuchi T., Sasaoka T., et al. (2023). Quantitative analysis of NMDA receptor subunits proteins in mouse brain. Neurochem. Int. 165, 105517. 10.1016/j.neuint.2023.105517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. C., Beitchman J. A., Pomerleau F., Noel T., Jungsuwadee P., Butterfield D. A., et al. (2017). Acute treatment with doxorubicin affects glutamate neurotransmission in the mouse frontal cortex and hippocampus. Brain Res. 1672, 10–17. 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn C. F., Oshiro C., Marsh S., Hernandez-Boussard T., McLeod H., Klein T. E., et al. (2011). Doxorubicin pathways: pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenetics Genomics 21, 440–446. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833ffb56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis S. F., Wollmuth L. P., McBain C. J., Menniti F. S., Vance K. M., Ogden K. K., et al. (2010). Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 405–496. 10.1124/pr.109.002451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ureshino R. P., Erustes A. G., Bassani T. B., Wachilewski P., Guarache G. C., Nascimento A. C., et al. (2019). The interplay between Ca2+ signaling pathways and neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 6004. 10.3390/ijms20236004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usmani M. T., Krattli R. P., El-Khatib S. M., Le A. C. D., Smith S. M., Baulch J. E., et al. (2023). BDNF augmentation using riluzole reverses doxorubicin-induced decline in cognitive function and neurogenesis. Neurotherapeutics 20, 838–852. 10.1007/s13311-022-01339-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Youle R. J. (2009). The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 95–118. 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfrum P., Fietz A., Schnichels S., Hurst J. (2022). The function of p53 and its role in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease compared to age-related macular degeneration. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1029473. 10.3389/fnins.2022.1029473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A., Vissel B. (2012). The essential role of AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit RNA editing in the normal and diseased brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 5, 34. 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Gong R., Qin L., Bao Y., Fu Y., Gao S., et al. (2022). Trafficking of NMDA receptors is essential for hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation. Cell Rep. 40, 111217. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Ju W., Zhang H., Sun L. (2018). Effect of ketamine on LTP and NMDAR EPSC in Hippocampus of the chronic social defeat stress mice model of depression. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12, 229. 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti L., Regoni M., Ratti E., Valtorta F., Sassone J. (2021). Presynaptic AMPA receptors in health and disease. Cells 10, 2260. 10.3390/cells10092260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Zhang B. (2017). Doxorubicin induces cardiotoxicity through upregulation of death receptors mediated apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 7, 44735. 10.1038/srep44735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Danbolt N. C. (2014). Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the healthy brain. J. Neural Transm. 121, 799–817. 10.1007/s00702-014-1180-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.