Abstract

Reversible protein phosphorylation plays important roles in signal transduction. One gene, prpA, encoding a protein similar to eukaryotic types of phosphoprotein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, and PP2B, was cloned from the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Interestingly, a eukaryotic-type protein kinase gene, pknE, was found 301 bp downstream of prpA. This unusual genetic arrangement provides the opportunity for study about how the balance between protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation can regulate cellular activities. Both proteins were overproduced in Escherichia coli and used to raise polyclonal antibodies. Immunodetection and RNA/DNA hybridization experiments suggest that these two genes are unlikely to be coexpressed, despite their close genetic linkage. PrpA is expressed constitutively under different nitrogen conditions, while PknE expression varies according to the nature of the nitrogen source. Inactivation analysis in vivo suggests that PrpA and PknE function to ensure a correct level of phosphorylation of the targets in order to regulate similar biological processes such as heterocyst structure formation and nitrogen fixation.

Protein phosphorylation or dephosphorylation is a prominent mechanism found in all living organisms for mediating signal transmission. For many years, protein kinases and phosphoprotein phosphatases that catalyze protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, respectively, were thought to be different in prokaryotes and eukaryotes: protein phosphorylation occurs mainly on histidine and aspartic acid residues in prokaryotes but on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues in eukaryotes. During the last few years, however, eukaryotic-type protein kinases and phosphatases have been reported in several bacteria, and homologs of prokaryotic protein kinases have been discovered in eukaryotes (for reviews, see references 1, 2, 16, 19, and 30). These studies suggest that eukaryotes and prokaryotes have similar mechanisms for signal transmission.

The relative activities of protein kinases and phosphatases determine the extent of phosphorylation at a particular site, which can in turn modulate the function of target proteins (16). Although initial studies on protein phosphorylation were concentrated on protein kinases, recent development in the understanding of protein phosphatases has firmly established that phosphatases are as important as kinases in signal transduction. Protein phosphatases in eukaryotes can be divided into two main groups based on their enzymatic specificity: Ser/Thr phosphatases and Tyr phosphatases (10, 26). The Ser/Thr-specific phosphatases show broad and overlapping specificities in vitro and have been grouped into four classes, PP1, PP2A, PP2B, and PP2C, according to their sensitivities to different inhibitors and their dependence on ions (3, 10, 17, 26). Amino acid sequence comparison indicates that PP1, PP2A, and PP2B are members of the same gene family, whereas PP2C represents a distinct gene family (3). The activities of PP1 and PP2A are not dependent on divalent cations, but those of PP2B and PP2C are affected by the presence of Ca2+ and Mg2+, respectively. PP1 is sensitive to nanomolar concentrations of inhibitor 1 and 2, while PP2A, PP2B, and PP2C are resistant (3, 17).

Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (referred to hereafter as Anabaena) is a filamentous cyanobacterium that can modulate its cellular activity, including the differentiation of heterocysts devoted to nitrogen fixation, in response to environmental factors. After combined-nitrogen deprivation, heterocyst differentiation occurs following a semiregular pattern along each filament, with interheterocyst spacing ranging between 10 and 20 vegetative cells. The semiregular pattern is maintained during subsequent cell growth on dinitrogen, as new heterocysts arise between two existing ones (for reviews, see references 7 and 27). Mutations that disturb the heterocyst pattern usually affect cell growth in the absence of a combined-nitrogen source as well (5, 6, 8, 14, 20, 21). Late in heterocyst development, the nitrogenase responsible for nitrogen fixation begins to be synthesized. Heterocysts have a thick envelope with a glycolipid layer surrounded by polysaccharides. This structure ensures a microanaerobic environment within the heterocyst, preventing the inactivation of nitrogenase by oxygen (7, 27).

The presence of a family of Ser/Thr kinase-like proteins, which are well-documented signal transduction components in eukaryotes, has been demonstrated in Anabaena (29–31). This prompted us to search for cognate protein phosphatases within this strain. Here we report the isolation and characterization of a gene cluster with two open reading frames (ORFs) separated by only 301 bp that encode a phosphoprotein phosphatase and a protein kinase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Anabaena is grown, as already described (24, 29), in BG11 with either 18 mM of NaNO3 or 5 mM of NH4Cl (buffered with 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5]) as the combined nitrogen source or with BG110, in which 18 mM of NaCl replaces the combined nitrogen. Escherichia coli strains used for cloning and conjugation are already described (12, 29).

PCR.

To search for protein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, and PP2B, the two following PCR primers were used (R as purine, Y as pyrimidine, N as any of the four nucleobases): RW191, CTTGGATCCGGNGANRTNCAYGG (from the conserved motif GD I/V HG [11]); RW193, CTTGGATCCTCRTGRTTNCCNC (from the conserved motif RGNHE [11]). PCR was performed as described in reference 29, except that the annealing temperature was 57°C. The clones obtained after insertion into the BamHI site of pBluescript SK− were analyzed by DNA sequencing and digestion with suitable restriction enzymes. The screening of the genomic library is described in reference 29.

Protein overexpression and immunotechnology.

Both prpA and pknE genes were amplified with PCR primers tagged with appropriate restriction sites. The amplified catalytic domain-encoded region of PrpA corresponds to the first 517 amino acid residues of the entire PrpA protein. The inserts were cloned into either pET15b (Novagen) or pGEX-2T (Pharmacia). The pET15b constructs give rise to His-tagged recombinant proteins, whereas the pGEX-2T constructs give rise to glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion.

For antiserum production, His-tag fusion constructs were used. The plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21, and cells were grown at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 and induced by 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactoside). The culture was further incubated for another 3 h and then collected by centrifugation and resuspended into the binding buffer (5 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris [pH 7.9]). Cells were disrupted by sonication, and the recombinant proteins were purified under denaturing conditions with urea with a His.Bind affinity column (Novagen). The purification procedure followed the supplier’s protocol. Each protein was further purified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and used to inject two rabbits for the production of antiserum.

For purification of soluble GST fusion proteins, E. coli transformants were cultured at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6 and then further incubated for 3 h at 15°C in the presence of 0.5 mM IPTG. Cells were collected and resuspended in TBS buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl). After sonication, the insoluble protein fraction was eliminated by centrifugation, and the soluble fraction was passed through a GST Sepharose 4B affinity column (Pharmacia) following the supplier’s recommendations. The purified protein solution contained 10 mM glutathione and 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0).

The immunodetection technique was as already described (31).

Assay of phosphatase activity.

To test phosphatase activity, 20 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) was incubated with purified GST-PrpA fusion or with purified GST as a control in TBS buffer at 30°C in the presence of different ions or without ions. The reaction was then monitored by measuring the optical density at 410 nm (22).

Construction of prpA and pknE mutants.

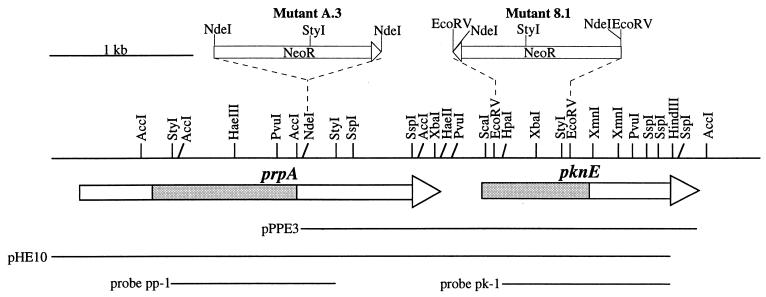

A 4.4-kb HindIII fragment bearing the prpA gene and a partial pknE gene (Fig. 1) was cloned into the HindIII site of pBluescript SK−, giving rise to plasmid pHE10 (Fig. 1). The neomycin-resistant gene cassette was PCR amplified from pUC4K (Pharmacia) by a pair of primers bearing EcoRV/NdeI sites. The PCR products were digested either with NdeI and inserted into the unique NdeI site of pHE10 or with EcoRV and inserted into the double EcoRV sites of the pknE gene of pHE10. The former construct (pNEOA) disrupted the prpA gene, while the latter (pNEO8) disrupted the pknE gene (Fig. 1). The inserts of these two constructs were then cloned respectively into the PstI/XhoI sites of the conjugative vector pRL271 (12). The prpA and pknE mutants were obtained by conjugation as described in reference 12. Southern hybridization experiments confirmed that these two genes were completely inactivated (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the prpA-pknE region. The coding regions of the two genes are shown by arrow bars below the restriction map. Shaded regions correspond to the catalytic domains of PrpA and PknE. DNA fragments (pHE10, pPPE3, pp-1, and pk-1) relevant to the text are also shown. The strategies used to inactivate either the prpA gene or the pknE gene are illustrated above the restriction map (for details, see Materials and Methods).

Nitrogenase assays and analysis of glycolipids.

The nitrogenase assay was performed by measuring the acetylene reduction by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectroscopy as described previously (13, 31). Glycolipids were extracted and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography as described by Black et al. (4).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this study has been submitted to the EMBL data bank under accession no. AJ224354.

RESULTS

Search for Ser/Thr phosphatase homologs in Anabaena.

Two oligonucleotides have been designed against conserved regions of PP1-, PP2A-, and PP2B-type Ser/Thr phosphatases (11). PCR with these degenerate oligonucleotides as primers in the presence of 0.3 μg of chromosome DNA from Anabaena gave rise to a predominant DNA fragment of about 270 bp. This PCR product was cloned into the pBluescript vector, and five clones (PCR-PRP1 to PCR-PRP5) were sequenced. Their deduced amino acid sequences were identical and showed significant similarity to those of PP1-, PP2A-, and PP2B-type protein phosphatases. In particular, the sequence motif FLGDLVDR, found in the middle of the deduced sequence, was conserved in all PP1-, PP2A-, and PP2B-type protein phosphatases (data not shown). We designated this novel protein phosphatase PrpA. In order to determine if different protein phosphatases were also amplified by the two degenerate primers, 19 more clones were analyzed by comparing their restriction patterns with that of PCR-PRP1 and by DNA sequencing. However, all the clones were the same as those previously identified (data not shown).

Cloning and sequencing of prpA.

The PCR-PRP1 insert was used as a probe to screen a genomic bank of Anabaena, and one positive clone was identified. Results from Southern hybridization with plasmid DNA isolated from this clone indicated that the prpA gene is located on a 4.4-kb HindIII fragment at one end of the insert.

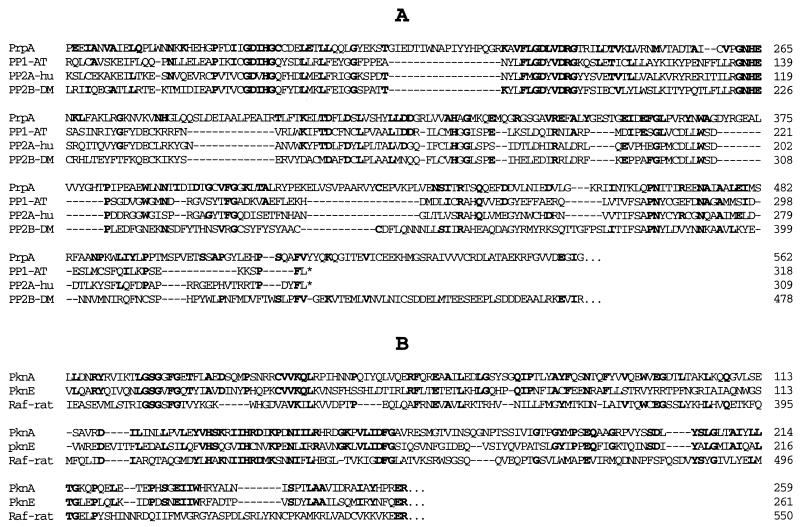

The 4.4-kb HindIII fragment plus a 271-bp region after the HindIII site was sequenced (Fig. 1). The first ORF in this region was identified as prpA, since it covers the region of the PCR-PRP1 insert. Two ATG codons are located at 191 and 467. The first ATG is likely to be the initiation codon, since this is in agreement with the size of the PrpA catalytic domain expressed in E. coli (58.092 kDa rather than the 48.051 kDa, indicating that the second ATG is the initiation codon; data not shown). The predicted PrpA protein is thus composed of 858 residues, with a calculated molecular weight of 96,808. One region of PrpA (from position 158 to 518) shows strong sequence similarity to PP1, PP2A, and PP2B Ser/Thr phosphatases. It is 23% identical to PP1 in Arabidopsis thaliana (23), 21% identical to PP2A in humans (25), and 16.5% identical to PP2B in Drosophila melanogaster (15). A small region (from 519 to 542) shows limited sequence similarity to PP2B-type Ser/Thr phosphatases (15). All major clusters of conserved sequences of PP1, PP2A, and PP2B phosphatases can be found in the PrpA sequence (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence comparison between PrpA and Ser/Thr phosphatases (A) and PknE and Ser/Thr kinases (B). Identical residues are in bold-faced type. Gaps (indicated by dashes) were introduced to optimize sequence alignment. PP1-AT, protein phosphatase 1 in A. thaliana (23); PP2A-hu, human protein phosphatase 2A (25); PP2B-DM, protein phosphatase 2B in D. melanogaster (15); PknA, protein kinase in Anabaena (29); Raf-rat, the Ser/Thr kinase Raf in rats (18).

A protein kinase gene (pknE) is located downstream of prpA.

Three hundred one bases downstream of the prpA gene is a second ORF, whose deduced amino acid sequence is similar to protein Ser/Thr kinases (Fig. 1 and 2). This ORF, designated pknE, represents a putative protein kinase different from those previously identified by PCR (29, 31). The pknE gene predicts a protein of 475 residues with a molecular weight of 53,359. The region containing 280 residues at the N-terminal part of PknE is 37% identical to the corresponding region of PknA in Anabaena (29) and 15.5% identical to the catalytic domain of the mammalian oncogene Raf kinase (18). The C-terminal part of PknE does not show sequence similarity to any proteins in the data banks.

Biochemical characterization of PrpA.

Both prpA and pknE were overexpressed in E. coli as His-tagged fusion proteins with the vector pET15b under the control of the T7 RNA polymerase. The sizes of the expressed proteins correlated well with the molecular weights predicted from the DNA sequence. Both the His-tagged, recombinant PrpA and PknE proteins were purified and used for the production of antisera in order to examine the protein level expressed under different conditions (see below).

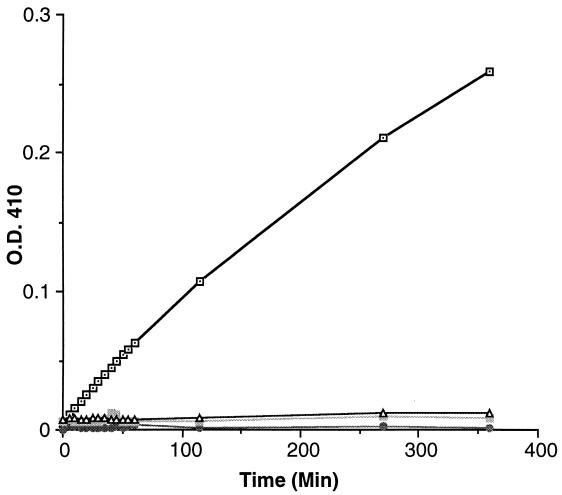

We sought to determine whether the recombinant PrpA protein possesses phosphatase activity, using pNPP as the substrate (11, 22). The His-tagged fusion protein produced in E. coli was found only in the insoluble fraction, even when the culture temperature was lowered to 15°C. The PrpA was thus also produced as a fusion to GST. A very small proportion, less than 5% of the total protein induced, of the GST-PrpA fusion was found in the soluble fraction from E. coli cells cultured at 15°C. The soluble GST-PrpA fusion was then purified by affinity chromatography with glutathione Sepharose 4B. The purified GST-PrpA fusion did indeed show phosphatase activity with pNPP as the substrate, but only in the presence of Mn2+ (Fig. 3). GST-PrpA was inactive with pNPP as the substrate, both in the presence of either Ca2+ or Mg2+ and in the absence of any ions. As a control, the GST was purified and assayed under the same conditions as the GST-PrpA fusion and showed no detectable phosphatase activity (Fig. 3). When only the catalytic domain of PrpA was produced as a GST fusion, the phosphatase activity was similar to that of the entire GST-PrpA (data not shown). The requirement of Mn2+ for enzymatic activity has been previously observed for other protein phosphatases similar to PrpA (32).

FIG. 3.

Hydrolysis of pNPP by the recombinant GST-PrpA fusion protein. The affinity-column-purified proteins (GST and GST-PrpA fusion) were incubated at 30°C in the presence of different ions. The hydrolysis of pNPP was followed by measurement of the change in OD410 (22). ⊡, GST-PrpA with 2 mM Mn2+;  , GST with 2 mM Mn2+;

, GST with 2 mM Mn2+;  , GST-PrpA with 2 mM Ca2+; and ▵, GST-PrpA with 2 mM Mg2+.

, GST-PrpA with 2 mM Ca2+; and ▵, GST-PrpA with 2 mM Mg2+.

Regulation of prpA and pknE expression during heterocyst development.

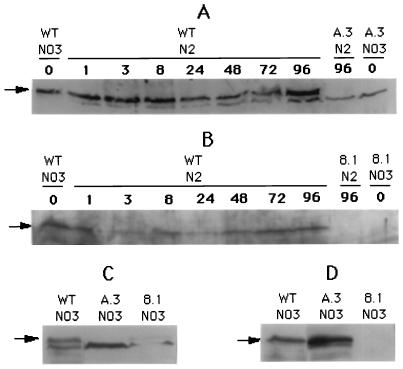

The polyclonal antisera prepared against PrpA and PknE were used to detect the expression of the two proteins under various conditions. The specificities of the antisera were first controlled with total proteins extracted from an E. coli strain expressing the antigen. Total proteins of Anabaena were extracted from cells first cultured in the presence of nitrate and then transferred to combined nitrogen-limiting medium for heterocyst induction. One antiserum against PrpA detected a protein from the wild-type Anabaena that was absent from the prpA mutant A.3 (see below and Fig. 4A). The estimated size of the protein, approximately 95 kDa, is in good agreement with the value predicted from the DNA sequence. The level of PrpA expression, after correction for the relative amount of total proteins estimated from Coomassie blue staining, shows little variation during heterocyst differentiation. The antiserum also detected a protein slightly smaller in size than PrpA that requires further characterization.

FIG. 4.

Expression of PrpA and PknE examined by Western blotting. Total proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto Immobilon membrane for Western analysis with antibodies against either PrpA (A and C) or PknE (B and D). To check the protein expression during heterocyst development (A and B), similar amounts of total proteins were loaded onto each lane of the gel. Protein samples were prepared from cells grown in the presence of nitrate (lanes 0, NO3) or transferred to nitrate-free medium (N2) for 1 to 96 h (lanes 1 to lanes 96).

One anti-PknE serum was able to interact with a protein of 53 kDa that was absent from the pknE mutant 8.1 (see below and Fig. 4B). The size of this protein is close to the predicted molecular weight of PknE. Its expression level is high in cells cultured in the presence of nitrate, decreasing slightly 3 h after the transfer to dinitrogen and then increasing again after longer incubation with dinitrogen (Fig. 4B).

Are PrpA and PknE coexpressed?

A DNA fragment encoding the C-terminal region of PrpA and the entire PknE protein (pPPE3, Fig. 1) was inserted into the expression vector pET3a under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter in E. coli. After induction, only a polypeptide of about 36 kDa corresponding to the C-terminal region of PrpA was detected and no trace of the 53-kDa PknE protein was visible (data not shown). This result suggests that, at least in E. coli, prpA and pknE may not form an operon.

Furthermore, PrpA was detected by its antiserum in the pknE mutant 8.1 but not in the prpA mutant A.3 (see below and Fig. 4C). Similarly, the antiserum against PknE was still able to detect the expression of PknE in the mutant A.3 but not in the mutant 8.1 (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that pknE may be expressed from its own promoter, although the possibility cannot be ruled out that the PknE protein detected in the mutant A.3 is expressed from the promoter of the Neor cassette (Fig. 1).

RNA/DNA hybridization experiments were also performed with total RNA isolated from cells transferred from nitrate-containing to combined-nitrogen-limiting media (29). The probes pp-1 and pk-1 (Fig. 1) were used to detect the expression of prpA and of pknE, respectively. One messenger RNA of about 3.55 kb was found with the pk-1 probe, and the amount detected was high in cells cultured in the presence of nitrate, diminishing 2.5 h after the transfer and increasing again 11 h after the transfer (data not shown). This result is consistent with that obtained by immunodetection (Fig. 4B). However, no messenger RNA was detected with the pp-1 probe, suggesting that prpA is expressed at a low level. Also, the pknE transcript detected with the pk-1 probe is too short to cover both the prpA and the pknE genes. These combined results, along with the fact that the two genes show different expression patterns (Fig. 4A and B), suggest that prpA and pknE may be expressed independently.

Genetic analysis of prpA and pknE mutants.

The prpA and pknE genes were inactivated in vivo. The prpA mutants (A.3 and B.2) were obtained by the insertion of a Neor cassette into one NdeI site within the prpA coding region (Fig. 1), and the pknE mutants (2.1, 2.2, and 8.1) were prepared by inserting the Neor cassette in the place of a 0.5-kb EcoRV fragment within the pknE gene (Fig. 1). Southern hybridization experiments confirmed that the mutants obtained were completely segregated (see Materials and Methods). A.3 and 8.1 were used for further analysis.

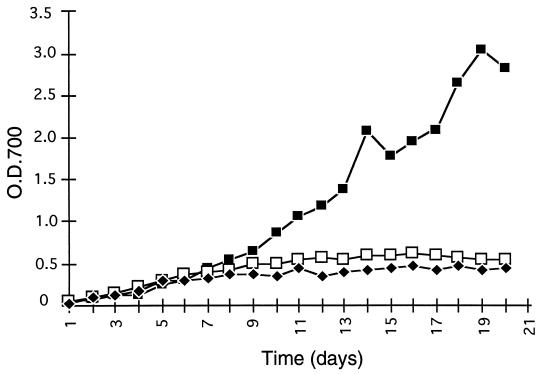

Both A.3 and 8.1 mutants grew normally, as did the wild type in the presence of either nitrate or ammonium as combined-nitrogen source (data not shown). When the two mutants were transferred to N2-fixing conditions (BG110 medium), their growth stagnated after 4 to 5 days, while the wild-type cells continued to grow (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Growth curves of the wild type (▪), the prpA mutant A.3 (□), and the pknE mutant 8.1 (⧫) under N2-fixing conditions. Cells were incubated in a combined nitrogen-free medium (BG110) at 30°C in air. Cell growth was monitored by measuring the OD700.

Twenty-four hours after the combined-nitrogen deprivation, both A.3 and 8.1 developed a normal heterocyst pattern as did the wild type. Heterocyst structure was aberrant in both mutants, being more transparent, with many half empty. About 4 days later, the cultures became yellowish green, and filaments of 8.1 mutants were fragmented. In both mutants, after 1 week in BG110, many cells appeared hollow and cell lysis became increasingly evident as indicated by the appearance of cell debris observed under the microscope.

Nitrogenase activity and glycolipid synthesis in A.3 and 8.1 mutants.

To determine whether nitrogen fixation activity was impaired in A.3 and 8.1 mutants, we performed nitrogenase assays with both mutants and the wild type. Under aerobic conditions, nitrogenase activity in the A.3 mutant is only about 2.2 and 3.4% of that of the wild type 2 and 4 days after combined-nitrogen stepdown, respectively (Table 1). The nitrogenase activity in the pknE mutant 8.1 is also affected, as its nitrogenase activity is 13.1 and 10.6% of that of the wild type 2 and 4 days after the cells were transferred into N2-fixing conditions, respectively. Exposing the cells to anaerobic conditions only partly restores the nitrogenase activity in the A.3 and 8.1 mutants, as the nitrogenase activity reaches about 21.7 and 26.9%, respectively, of that of the wild type under similar conditions (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Relative activity of nitrogenase in wild-type and mutant strainsa

| Condition and no. of days in BG110 | Nitrogenase activity (%) for indicated strain

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | prpA mutant (A.3) | pknE mutant (8.1) | |

| Anaerobic | |||

| 2 | 100 | 21.7 | 26.4 |

| 4 | 100 | 21.8 | 26.9 |

| Aerobic | |||

| 2 | 100 | 2.2 | 13.1 |

| 4 | 100 | 3.4 | 10.6 |

Cells were cultured for 2 or 4 days in BG110, and then the standard acetylene reduction assay was performed (13, 31) with 20% acetylene either in air (aerobic conditions) or in argon in the presence of 10 μM dichlorodimethylurea (anaerobic conditions). The amount of ethylene produced was used to compare the activity of nitrogenase of the two mutants relative to that in the wild-type strain. The values shown are the means of at least three measurements in the exponential phase of ethylene production.

Since the nitrogenase activity under anaerobic conditions was stronger than that under aerobic conditions in the two mutants, we analyzed their glycolipids, which play a critical role in the protection of nitrogenase against oxygen inactivation (7, 27). After extraction with methanol-chloroform from cells cultured in either nitrate, ammonium, or dinitrogen, glycolipids were separated and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography. Similar profiles of glycolipids were obtained from the wild type and the two mutants (data not shown). The glycolipids induced under nitrogen-limiting conditions were also present in the prpA mutant A.1 and the pknE mutant 8.1.

DISCUSSION

The protein phosphatase PrpA characterized here, although homologous to the entire catalytic domains of PP1, PP2A, and PP2B, is not easily classified within any group of protein phosphatases based on the sequence similarity of the catalytic domains, since the degree of sequence similarity between PrpA and PP1 is close to that between PrpA and PP2A or between PrpA and PP2B (Fig. 2A). We were able to clone only one protein phosphatase gene from Anabaena by the approach used here, and no PP2C-type protein phosphatase could be detected by a similar approach (data not shown). However, by analogy with other organisms, a family of protein phosphatase genes can also be expected from Anabaena, in which a family of Ser/Thr kinases has been identified (29–31). The antiserum against PrpA reacts strongly with another protein of 92 kDa, which may be a PrpA homolog in Anabaena. Curiously, one gene encoding a protein similar to the catalytic domains of Ser/Thr phosphatases of types PP1, PP2A, and PP2B is found on the entire genome of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (Cyanobase data bank). This protein, however, has no C-terminal regulatory sequence, as does PrpA, and no polypeptide similar to the C-terminal region of PrpA was detected in the Cyanobase. This result may suggest that prpA reported in this study is involved in the regulation of a biological process in Anabaena, such as nitrogen fixation or cell differentiation, that is absent from the unicellular strain Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803.

The prpA and pknE genes are closely linked on the chromosome, although their products have rather antagonistic actions. This unusual genetic organization offers an opportunity to study how the coordinated processes of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation ensure a balanced response to informational change in signal transduction. We are aware of only one example from Bacillus subtilis in which a close linkage between genes encoding protein kinases and phosphatases was reported (28). Two pairs of protein kinases and protein phosphatases encoded by a gene cluster in B. subtilis interact with each other by a partner-switching mechanism to transmit signals of environmental stress (28). It was also shown in human neurons that the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A and the protein phosphatase 2B bind to a common anchoring protein, thereby forming a single protein complex to ensure their enzymatic specificity toward the common target (9). The inactivation of either prpA or pknE affects similar biological processes (heterocyst structure development, cell growth under N2-fixing conditions, and nitrogen fixation activity), strongly suggesting that these two genes are involved in the regulation of similar targets in Anabaena. Both prpA and pknE mutants produce heterocysts with aberrant structures, which may account for their poor performance in nitrogen fixation and, ultimately, their inability to sustain growth in the absence of combined nitrogen. It is, however, difficult to pinpoint the defects of heterocyst structures of these mutants under the light microscope. The heterocyst-specific glycolipid synthesis, which is critical for nitrogen fixation (7, 27), is not affected by the inactivation of either prpA or pknE.

Since prpA and pknE are closely linked on the chromosome, we used different approaches to attempt to determine their genetic organization. Our results support the possibility that they are not necessarily cotranscribed, although additional experiments will be required to substantiate this conclusion. Our data suggest that prpA is constitutively expressed under the conditions tested here, while the expression of pknE is regulated during the process of heterocyst development. Immunoblotting and RNA/DNA hybridization experiments indicate that pknE is strongly expressed in the presence of nitrate, with its expression decreasing during the first few hours of nitrate deprivation and then increasing again. These observations suggest that the equilibrium between protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in response to environmental changes is regulated at the level of the protein kinase. The inactivation of a protein kinase or a protein phosphatase leads to unchecked protein dephosphorylation or phosphorylation, respectively, resulting in a misregulation of cell activity (16). The results of our studies demonstrate the importance of maintaining protein phosphorylation at a correct level, which requires the actions of both protein kinase and protein phosphatase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie and by the ESBS.

We thank Jean-François Lefèvre for his constant support, Patrick Wehrung for his help in gas chromatography, and Amy Krische for correction of our English.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alex L A, Simon M I. Protein kinase and signal transduction in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Trends Genet. 1994;10:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleby J L, Parkinson J S, Bourret R B. Signal transduction via the multi-step phosphorelay: not necessarily a road less traveled. Cell. 1996;86:845–848. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barford D. Molecular mechanisms of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:407–412. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black K, Buikema W J, Haselkorn R. The hglK gene is required for localization of heterocyst-specific glycolipids in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6440–6448. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6440-6448.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black T A, Wolk C P. Analysis of Het− mutation in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 implicates a secondary metabolite in the regulation of heterocyst spacing. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2282–2292. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2282-2292.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buikema W J, Haselkorn R. Characterization of a gene controlling heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Genes Dev. 1991;5:321–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buikema W J, Haselkorn R. Molecular genetics of cyanobacterial development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1993;44:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell E L, Hagen K D, Cohen M F, Summers M L, Meeks J C. The devR gene product is characteristic of receivers of two-component regulatory systems and is essential for heterocyst development in the filamentous cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. strain ATCC 29133. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2037–2043. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2037-2043.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coghlan V M, Perrino B A, Howard M, Langeberg L K, Hicks J B, Gallatin W M, Scott J D. Association of protein kinase A and protein phosphatase 2B with a common anchoring protein. Science. 1995;267:108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7528941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen P. The structure and regulation of protein phosphatases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen P T W. Cloning of protein-serine/threonine phosphatases. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:398–408. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elhai J, Wolk C P. Conjugal transfer of DNA to cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:747–754. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst A, Black T, Cai Y, Panoff J-M, Tiwari D N, Wolk C P. Synthesis of nitrogenase in mutants of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 affected in heterocyst development or metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6025-6032.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Pinas F, Leganes F, Wolk C P. A third genetic locus required for the formation of heterocysts in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5277–5283. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5277-5283.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong C S, Ganetzky B. Molecular characterization of neurally expressing genes in the para sodium channel gene cluster of Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;142:879–892. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signalling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingebritsen T S, Cohen P. Protein phosphatases: properties and role in cellular regulation. Science. 1983;221:331–338. doi: 10.1126/science.6306765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa F F, Takaku M, Nagao M, Sugimura T. Rat c-raf oncogene activation by a rearrangement that produces a fused protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1226–1232. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennelly P J, Potts M. Fancy meeting you here! A fresh look at “prokaryotic” protein phosphorylation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4759–4764. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4759-4764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang J, Scappino L, Haselkorn R. The patA gene product, which contains a region similar to CheY of Escherichia coli, controls heterocyst pattern formation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5655–5659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang J, Scappino L, Haselkorn R. The patB gene product, required for growth of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 under nitrogen-limiting conditions, contains ferredoxin and helix-turn-helix domains. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1697–1704. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1697-1704.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacKintosh C. Assay and purification of protein (serine/threonine) phosphatases. In: Hardie D G, editor. Protein phosphorylation, a practical approach. Oxford, England: IRL Press; 1993. pp. 197–230. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nitschke K, Fleig U, Schell J, Palme K. Complementation of the cs dis2-11 cell cycle mutant of Schizosaccharomyces pombe by a protein phosphatase from Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 1992;11:1327–1333. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury J B, Herdman M, Stanier R Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone S R, Mayer R, Wernet W, Maurer F, Hofsteenge J, Hemmings B A. The nucleotide sequence of the cDNA encoding the human lung protein phosphatase 2A alpha catalytic subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:11365. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.23.11365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villafranca J E, Kissinger C R, Parge H E. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolk C P. Heterocyst formation. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:59–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X, Kang C M, Brody M S, Price C W. Opposing pairs of serine protein kinases and phosphatases transmit signals of environmental stress to activate a bacterial transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2265–2275. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C-C. A gene encoding a protein related to eukaryotic protein kinases from the filamentous heterocystous cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11840–11844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C-C. Bacterial signalling involving eukaryotic-type protein kinases. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang C-C, Libs L. Cloning and characterisation of the pknD gene encoding an eukaryotic type protein kinase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:26–33. doi: 10.1007/s004380050703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Bai G, Deans-Zirattu S, Browner M F, Lee E Y C. Expression of the catalytic subunit of phosphorylase phosphatase (protein phosphatase-1) in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1484–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]