Introduction

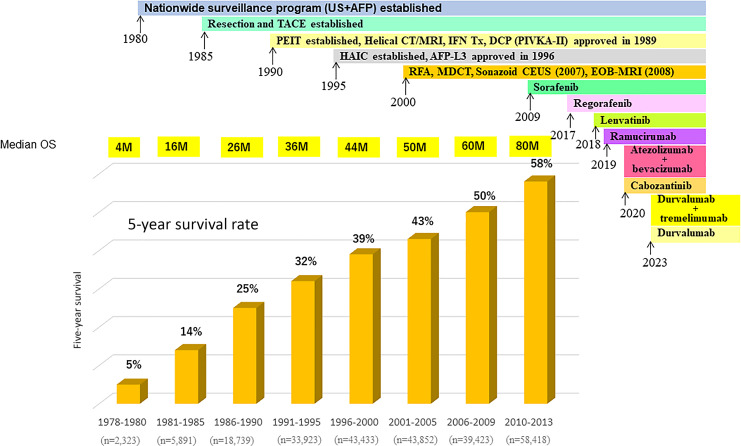

The treatment outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Japan have improved dramatically over the past 40 years and are probably the best in the world. According to the Nationwide Follow-up Survey by the Japan Liver Cancer Association (JLCA) (formerly Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan), the 5-year survival rate for the 2,323 cases registered between 1978 and 1980 is 5%, with a median overall survival (OS) of 4 months [1]. By contrast, among the 58,418 patients with all stages of HCC enrolled between 2010 and 2013, the 5-year survival rate is 58% and the median OS is 80 months (Fig. 1) [2–6]. The number of patients with HCC has increased steadily since the 1980s, and the improved survival of these patients is due to several factors, including the establishment of a nationwide surveillance system for HCC in the 1980s, the use of safe techniques for resection and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), the development of ethanol injection therapy in the 1990s, the increased use of helical computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis, the reimbursement approval of protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) measurement (1989), the expanded use of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) in the 1995s, the development of AFP-L3 in 1996, the widespread use of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in 2004, and the increased application of multidetector computed tomography in routine clinical practice (Fig. 1) [6]. In addition, the approval of several therapeutic agents such as the molecular-targeted agent sorafenib [7] in 2009, regorafenib in 2017 [8], lenvatinib [9] in 2018, ramucirumab in 2019 [10], and cabozantinib in 2020 [11] likely contributed to the improved survival. The combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab (Atezo/Bev) [12] was approved in 2020 and the combination of durvalumab plus tremelimumab and durvalumab monotherapy [13] were approved in 2023 in Japan (Fig. 1). These systemic therapies may be related to the improved prognosis of patients enrolled between 2010 and 2013 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Improvement of median OS and 5 years survival rate in patients with all stages of HCC in Japan (modified from Kudo [6]).

The latest Nationwide Follow-up Survey by JLCA [5] shows that 48% of cases registered in 2016–2017 underwent resection, 19% had local ablation therapy, and 27% underwent TACE; approximately 67% of cases received curative treatments such as resection or RFA as the initial treatment. The proportion of patients undergoing resection has increased gradually since the year 2000, when resection was the initial treatment in 28–29% of patients [6]. This increase may be due to the increasing proportion of HCCs of non-viral etiology, especially nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related HCCs, which show a lower degree of fibrosis and preserved liver function [6, 14]. Unlike viral HCCs, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related HCCs are large at the time of detection because patients at high risk of HCC are not identified effectively. However, many patients maintain good liver function and show a low degree of fibrosis, which makes them eligible for resection. Non-viral HCCs account for 60–70% of surgical resections. This editorial describes the current treatments for HCC in Japan.

Treatment of Early-Stage HCC (BCLC-0 and BCLC-A)

Resection or Local Ablation for Small HCC: Results of the SURF Trial

The SURF trial was a phase 3 prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in Japan that compared the efficacy of resection versus RFA [15]. Between 2009 and 2015, 308 patients with up to three HCC nodules (≤3 cm) who were eligible for both resection and RFA were enrolled from 49 centers in Japan. Although several RCTs of similar comparative studies were published previously [16–18], the studies analyzed included a small number of patients, ranging from 100 to 230. The SURF trial was initially designed to compare recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS between patients undergoing resection and RFA. The study was initiated with 600 cases (300 resections and 300 RFAs) to verify the superiority of resection over RFA regarding RFS and OS. The rationale for setting this number of cases was based on a study by Hasegawa et al. [19], assuming that resection outperforms RFA by 10% in 3- and 5-year survival rates, the number of cases required to statistically verify the superiority of resection with a power of 0.8 and an alpha value of 0.05 was calculated to be 600. However, case enrollment did not proceed as planned. In February 2016, the Independent Data Monitoring Committee recommended that further patient enrollment be halted because it was impractical, and the 308 enrolled patients were analyzed. The results showed no difference in RFS or OS between the two groups; RFS was 3.5 years in the resection group and 3.0 years in the ablation group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.67–1.25; p = 0.58), and the superiority of resection over RFA was thus not demonstrated. The results were presented at the 2019 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [20] meeting. The OS results were subsequently reported at the 2021 ASCO meeting but failed to show a significant difference, with a HR of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.64–1.43, p = 0.838) [21]. The results of the SURF non-randomized cohort study (propensity score matching of a cohort of patients who underwent RFA or resection under real-world clinical conditions) were presented at ASCO in 2022 [22]. Inverse probability of treatment weighting analysis showed that the 5-year RFS rate was 46.6% for 382 resected patients and 39.3% for 371 RFA patients (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.71–1.06; p = 0.155); there was no significant difference in OS: the 5-year survival rate was 79.7% for resection and 79.3% for RFA (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.75–1.30; p = 0.906) [22].

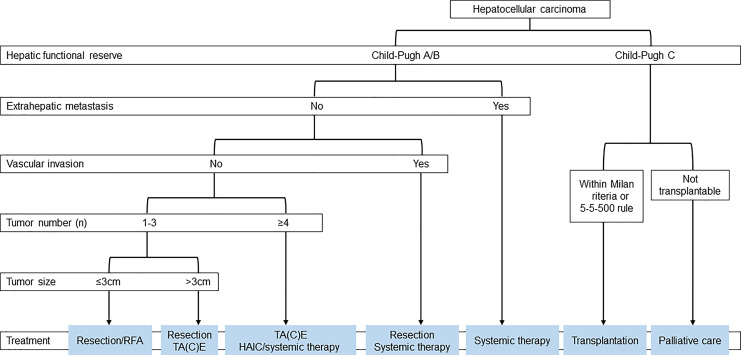

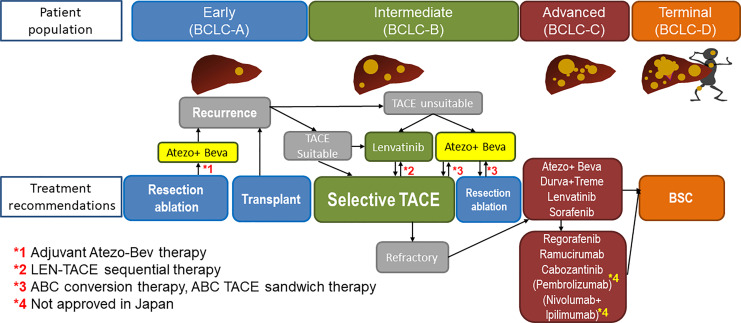

The results of the SURF trial suggest that the prognosis of patients does not differ between resection and RFA in cases in which both are feasible, namely, for nodules ≤3 cm in diameter and three or fewer nodules. Based on these results, the 2021 edition of the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma was revised to recommend resection and ablation equally for early-stage HCC (Fig. 2) [23, 24].

Fig. 2.

Treatment algorithm for HCC established by Japan Society of Hepatology in 2021 (cited from Hasegawa et al. [23]).

Clinical Trials of Adjuvant Therapy after Curative Treatment

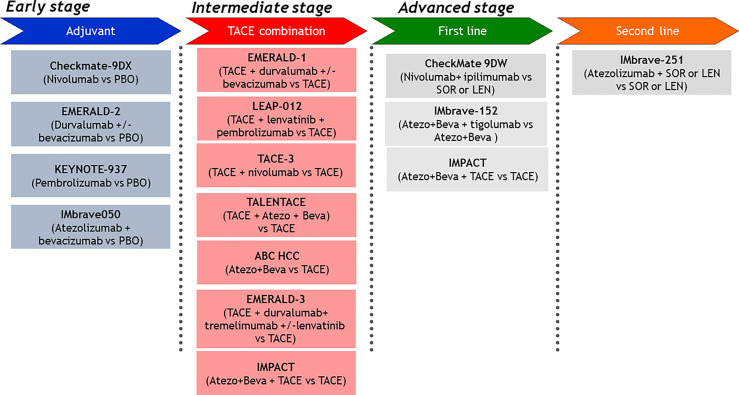

Four clinical trials of adjuvant therapy are ongoing (Fig. 3). Among them, positive results from the IMbrave050 trial were reported [25, 26]. We also conducted an exploratory multicenter single-arm phase 2 study (NIVOLVE trial, UMIN 000026648) of single-agent nivolumab that included 55 patients with HCC treated with liver resection or RFA. The results were presented at the 2021 ASCO meeting [27] and at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium (ASCO-GI) [28, 29] in 2022. The study included patients at intermediate and high risk for recurrence and excluded those with a single tumor <2 cm in diameter (low-risk recurrence group). These criteria are the same as those of the STORM trial [30]. The results showed that the RFS was 26.3 months. In addition, analysis of genetic mutations by next-generation sequencing, immunohistochemical staining for protein related to WNT/β-catenin signaling, and analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in patients who relapsed after resection indicated that the risk of recurrence was higher in: (1) patients with WNT/β-catenin mutations, (2) patients with regulatory T-cells (Tregs) infiltration, and (3) patients with low CD8-positive cell infiltration. These results suggest that immune checkpoint inhibitors alone have limited efficacy in suppressing recurrence, and improving the immune microenvironment by eliminating Tregs with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibodies or other drugs targeting VEGF is necessary to suppress recurrence. This anti-VEGF activity may explain the success of the IMbrave050 study, which combined atezolizumab with bevacizumab. If atezolizumab + bevacizumab is approved in the adjuvant setting in Japan, it will undoubtedly be used aggressively as adjuvant therapy after curative treatments (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Ongoing phase 3 clinical trials for HCC.

Fig. 4.

New paradigm of treatment strategy in HCC.

Treatment of Intermediate-Stage HCC (BCLC-B Stage)

Concept of TACE Refractoriness

A drastic paradigm shift in the treatment strategy for intermediate-stage HCC, defined in the AASLD and EASL guidelines [31, 32] as multiple HCCs, is currently taking place. The treatment recommended by the AASLD and EASL guidelines was TACE alone until recently. However, the 2021 edition of the JSH Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma recommends resection, systemic therapy, and HAIC in addition to TACE for multifocal HCCs with four or more tumors and large HCCs >3 cm in size (Fig. 2) [23]. The consensus-based JSH clinical practice guidelines, which were the first of its kind in the world regarding the concept of “TACE refractoriness,” were established in 2011 [33] and updated in 2014 [34]. After this, the concept of “TACE refractoriness” spread rapidly around the world [35, 36]. In Taiwan, sorafenib was initially indicated only for advanced HCC. However, after the concept of TACE refractoriness was clearly stated in the “Consensus-based Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Liver Cancer” in Japan [33, 34], the insurance system was changed accordingly [37, 38]. Two retrospective clinical studies that applied the TACE refractoriness criteria of the JSH showed that “patients who switched to molecular-targeted therapy as soon as TACE became refractory” had better survival than “patients who continued TACE after it had become refractory” [39, 40]. The OPTIMIS study, a global non-interventional prospective trial designed to validate the results of these retrospective clinical studies, also clearly demonstrated that switching to a molecular-targeted agent at the point of TACE failure was associated with a greater survival benefit [41]. Therefore, the concept of TACE failure/refractoriness and early transition to systemic therapy at that point has become almost a global consensus.

The Concept of TACE Unsuitability

Recently, the JSH and Asia-Pacific Primary Liver Cancer Expert Association (APPLE) proposed the concept of “TACE unsuitability” [24, 42]. “TACE unsuitability” refers to the following (1): conditions that are likely to become TACE-refractory (2), conditions that are likely to deteriorate to Child-Pugh B liver function due to TACE, and (3) conditions that are inherently resistant to TACE [42]. APPLE and the JSH published a “Consensus Statement and Recommendations” on this topic [24, 42]. Among these conditions, HCCs beyond the up-to-seven criteria are prone to TACE refractoriness or transition to Child-Pugh B. In such cases, prior administration of lenvatinib can (1) induce tumor necrosis and achieve downstaging (2), suppress the release of hypoxia-inducible cytokines (e.g., VEGF) induced by TACE and inhibit invasion and metastasis, and (3) exert an anti-VEGF effect, which normalizes tumor blood vessels and enhances the effect of TACE. LEN-TACE sequential therapy improves the prognosis of patients beyond the up-to-seven criteria compared with TACE alone [43] and is gradually becoming common practice for TACE-unsuitable HCCs in Japan [44]. In China, LEN-TACE was shown to improve PFS and OS compared with TACE alone or lenvatinib alone in patients with intermediate- and advanced-stage HCC [45, 46].

SORA-TACE Sequential Therapy

The administration of molecular-targeted agents with anti-VEGF activity prior to TACE can increase the efficacy of TACE by normalizing tumor vasculature and increasing microvessel density, interstitial pressure, and vascular permeability, thereby improving drug delivery [47]. Therefore, combining TACE with systemic therapy is recommended. Six trials have assessed the combination of TACE and molecular-targeted agents, and all of them showed negative results except the TACTICS trial [48–53], in which the primary endpoint was PFS. In the TACTICS trial, the HR for PFS was 0.59 (95% CI, 0.41–0.78) [51]. The HR for PFS in the BRISK-TA and ORIENTAL trials was also significantly better (0.61 [95% CI, 0.74–0.99] than TACE alone for BRISK-TA and 0.86 [0.74–0.99] for ORIENTAL) [52, 53]. However, the primary endpoint of the ORIENTAL and BRISK-TA trials was OS, and the trials failed [52, 53]. The HRs of the BRISK-TA and ORIENTAL trials, in which OS was the primary endpoint, and those of the SPACE, TACE-2, and post-TACE trials, in which PFS was the primary endpoint, did not show a significant prognostic benefit in TACE plus sorafenib compared with TACE alone.

The TACTICS trial showed that combination treatment significantly improved PFS, which was the primary endpoint, and there were high expectations regarding OS benefit, which was the co-primary endpoint. However, the final data showed that the OS in the TACE plus sorafenib group was 36.2 months (95% CI, 30.5–44.1), whereas that for TACE alone was 30.8 months (95% CI, 23.5–40.8) (HR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.61–1.22; p = 0.40) [54]. The negative OS results of the TACTICS trial were attributed to the following factors: (1) there were 156 patients in the phase 2 trial, which was thus underpowered to meet the OS requirement and (2) post-progression survival was highly extended (17.3 months) because 76.3% of the patients in the TACE alone group received post-trial treatment (including 50% treated with sorafenib). However, the longest OS (36.2 months) in the six clinical trials and the prolongation of OS by 5.4 months in the TACE plus sorafenib arm compared with the TACE alone arm suggest that TACE plus molecular-targeted agents is an effective strategy [55]. In addition, the results of the TACTICS trial suggest that OS cannot be used as the primary endpoint in combination trials of TACE and systemic therapy in an era in which effective post-trial therapies are available [54, 55]. Actually, primary endpoint of all of currently ongoing TACE combination trial is PFS (Fig. 4).

The correlation coefficient (r) between OS HR and PFS HR in the six TACE combination trials is 0.56 [54], indicating that although there is some correlation between PFS HR and OS HR, it is weaker than that in advanced HCC [56, 57]. In other words, this result is not consistent with the strong correlation coefficient of r = 0.84 in the PFS HR versus OS HR plot for first-line and second-line therapy for advanced HCC reported by Llovet et al. [56, 57]. This weak correlation may be attributed to the fact that PFS has a weaker impact on OS since post-progression survival has stronger impact on OS in case of intermediate-stage HCC [58]. According to the AASLD guidelines, the primary endpoints in clinical trials of TACE combined with systemic therapy can be PFS [56] or objective response rate (ORR) [59]. Subanalysis in the REFLECT trial showed that OR is a predictive marker of OS in individual patients [60].

The TACTICS trial also showed that (1) PFS and OS prolongation is superior in patients with HCC beyond the up-to-seven criteria than in patients within the up-to-seven criteria; (2) clinically meaningful PFS and OS prolongation occurs even in patients with HCC within the up-to-seven criteria; and (3) time to vascular invasion/extrahepatic spread is prolonged by combining TACE with sorafenib [51, 54, 55]. Therefore, the combination of systemic therapy and TACE is recommended in patients who are not suitable for TACE [61, 62].

LEN-TACE Sequential Therapy

Upfront administration of lenvatinib followed by TACE may be more effective than TACE alone in patients who are initially unsuitable for TACE, such as patients with bilobar multifocal disease [63]. In 2019, a proof-of-concept study showed that patients with HCC beyond the up-to-seven criteria respond better when treated with upfront lenvatinib followed by selective TACE [43]. The OS of the LEN-TACE group was 37.9 months versus 21.3 months in the TACE alone group (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.16–0.79; p < 0.01), suggesting the good efficacy of LEN-TACE. Lenvatinib, which has a high response rate, should be administered as the first-line treatment for intermediate-stage HCC patients with HCC exceeding the up-to-seven criteria. The response rate of lenvatinib was 40.6% in the REFLECT trial and 61.3% in the Japanese subpopulation with intermediate-stage HCC [64]. The reason for the high response rate of 73.3% in a proof-of-concept study could be that many TACE naïve patients have ALBI grade 1 liver function and therefore have fewer adverse events and a lower rate of dose reduction, interruption, and discontinuation, which allows the administration of high doses of lenvatinib [65]. The high response rate in the proof-of-concept study results from many patients receiving a full dose of lenvatinib. The high response rate may be attributed to the following factors: (1) lenvatinib induces tumor shrinkage and necrosis; (2) selective TACE can be curative when additional TACE is performed after lenvatinib, thus preserving liver function; (3) upfront lenvatinib therapy suppresses hypoxia-inducible cytokines such as VEGF, thereby inhibiting recurrent metastasis, and (4) normalization of tumor vasculature with lenvatinib reduces vascular permeability and intra-tumoral interstitial pressure; this facilitates the spread of lipiodol containing anticancer drugs throughout the tumor, thereby enhancing the embolic effect, which may lead to pathological complete response. Therefore, LEN-TACE sequential therapy is a theoretically effective treatment for intermediate-stage HCC exceeding the up-to-seven criteria and is currently the standard of care for intermediate-stage HCC with a high tumor burden in Japan [66]. The treatment strategies for HCC are changing dramatically, and the administration of lenvatinib prior to TACE has little disadvantages, at least in patients with a high tumor burden.

TACTICS-L, a prospective, multicenter, single-arm phase 2 trial showed similar results [67]. The TACTICS-L and TACTICS trials gradually led to the worldwide acceptance of the concept that “high tumor burden should be treated with systemic therapy first, followed by TACE” rather than TACE alone [51, 61]. This concept is reflected in various global guidelines such as AASLD [56, 68], ESMO [69], and BCLC [70].

ABC Conversion Therapy

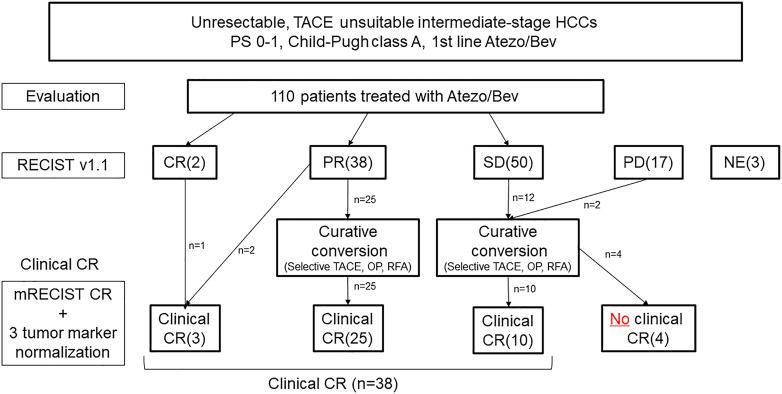

Atezo/Bev is a new regimen approved in 2020 based on the success of the IMbrave150 trial [12]. A high ORR of 44% in intermediate-stage HCC patients according to RECIST 1.1 was recently published [71, 72].

Of 110 patients with Child-Pugh grade A liver function included in a multicenter study of the Atezo/Bev combination in the first-line setting, 38 (35%) achieved clinical CR. These patients all achieved cancer-free status, which is defined as CR per mRECIST and the normalization of three tumor markers including AFP, PIVKA-II, and AFP-L3. In addition, 25 (23%) patients achieved drug-free status [73]. Seven cases achieved CR with resection, 13 with ablation, and 15 with curative TACE [73]. Three cases achieved cancer-free status with Atezo/Bev alone. As a result, the curative conversion rate was extremely high at 35% [73]. Unlike molecular-targeted drugs, Atezo/Bev has a strong tumor-shrinkage effect even in PET-positive HCCs with extremely high malignancy features, including poorly differentiated types. The results of this study indicate that pathological CR can be achieved and patients can achieve drug-free status (ABC conversion therapy) [74, 75].

In general, if a positive response to systemic therapy is obtained, it is common practice in oncology to continue the drug. Although this applies to advanced HCC, in intermediate-stage HCC or locally advanced HCC without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread, once tumor shrinkage is achieved, ablation, or curative TACE, as well as resection, are highly effective measures to achieve pathological CR. Therefore, continuing systemic therapy without performing curative conversion is not recommended. If tumor shrinkage is achieved with Atezo/Bev combination therapy, curative conversion should be considered while systemic therapy is effective to ensure the optimal timing for achieving clinical CR. Therefore, it is crucial to consider whether curative conversion is possible [62, 73–75]. Because OS is prolonged in patients who achieve curative conversion, the treatment strategy for intermediate-stage HCC should be different from the conventional sequential systemic therapy for advanced HCC [76].

The 44% response rate to Atezo/Bev treatment in intermediate-stage HCC [71, 72] indicates that one out of every 2 patients may undergo curative conversion. Therefore, the use of Atezo/Bev in intermediate-stage HCC results in high response rates. If a deep response is achieved, curative treatment should be initiated immediately instead of continuing the drug until progressive disease because, as with lenvatinib, achieving pathological CR with Atezo/Bev alone is not possible. Even when CR according to mRECIST is achieved, viable cancer cells (drug therapy resistant clone) may remain in the resected specimen, and, therefore, curative conversion should be performed whenever possible [62]. Even in cases of SD, slow progressive disease, or at the time of discontinuation due to adverse events, TACE may be effective during Atezo/Bev therapy to decrease tumor volume and release tumor antigens, which enhances cancer immunity cycle, resulting in clinical CR (ABC-TACE sandwich therapy) (Fig. 5) [73–75, 77].

Fig. 5.

Atezolizumab-bevacizumab followed by curative (ABC) conversion: Relationship between response to Atezo/Bev and achievement of clinical complete response (CR) (modified from Kudo [73]).

Ongoing Clinical Trials

Several clinical trials of TACE combined with immunotherapy are ongoing and the results are eagerly awaited. If positive results are obtained in at least one of these trials, the treatment strategies described above may become the standard of care (Fig. 3) [61].

Treatment of Advanced-Stage HCC (BCLC-C Stage)

First-Line Therapy for Advanced HCC

Atezo/Bev combination treatment was tested in a phase 3 trial with sorafenib as the control [12]. The results of the first interim analysis demonstrated the overwhelming statistical superiority of the Atezo/Bev combination over sorafenib regarding PFS and OS. These results marked a significant turning point in the history of sorafenib, which had been the standard first-line treatment for 11 years since 2009 in Japan. OS in the Atezo/Bev arm was not reached, whereas OS in the sorafenib group was 13.2 months (95% CI, 10.4–NE) (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42–0.79; p < 0.001). PFS was 6.8 months (95% CI, 5.7–8.3) in the Atezo/Bev group compared with 4.3 months (95% CI, 4.0–5.6) in the sorafenib group (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.47–0.76; p < 0.001). Adverse events were generally lower in the Atezo/Bev group than in the sorafenib group, and the time to deterioration of quality of life according to patient-reported outcomes was 11.2 months in the Atezo/Bev group versus 3.6 months in the sorafenib group (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.46–0.85). The Atezo/Bev combination treatment did not affect liver function and the ALBI score was maintained [78]. This result confirms the efficacy of the Atezo/Bev combination as the first-line treatment unless there is a contraindication to immunotherapy, such as in autoimmune diseases [24, 56, 69, 70, 79].

Updated OS data of 19.2 months were published for an extended follow-up period from 8.6 months at the interim analysis to 15.6 months (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52–0.85; p = 0.0009). The updated PFS in the Atezo/Bev group was 6.9 months (95% CI, 5.7–8.6) (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.53–0.81; p = 0.0001) compared with 4.3 months (95% CI, 4.0–5.6) in the sorafenib group [71]. The updated ORR in the Atezo/Bev arm was 30% (95% CI, 25–35) in the updated analysis. The ORR in the sorafenib group was 11% (95% CI, 7–17), which was almost unchanged from the ORR in the interim analysis. The duration of response in the Atezo/Bev group was 18.1 months compared with 14.9 months in the sorafenib group [71].

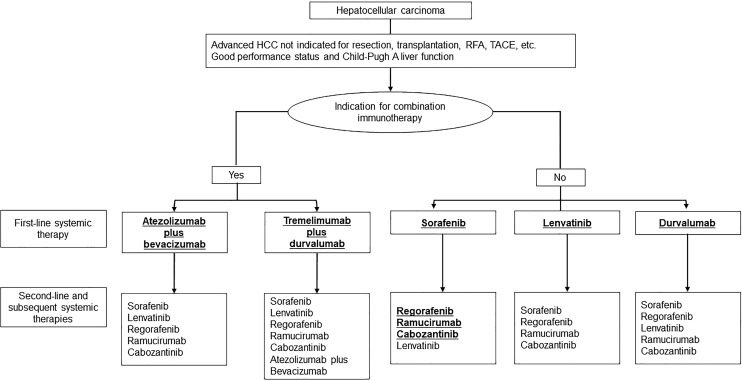

These results indicate that Atezo/Bev is the first-line regimen for advanced HCC as indicated by the JSH clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of HCC, the AASLD, and the ESMO and ASCO guidelines. Regarding second-line agents, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of the previous five drugs (lenvatinib, sorafenib, regorafenib, ramucirumab, and cabozantinib) as post-treatment for Atezo/Bev, although all are candidates.

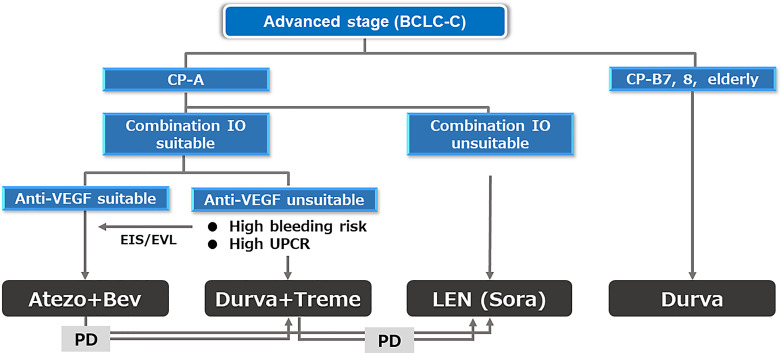

The phase 3 HIMALAYA trial showed the superiority of tremelimumab plus durvalumab (STRIDE regimen) [80, 81] over sorafenib, and this regimen and durvalumab monotherapy were approved as first-line treatment in Japan in 2023. The STRIDE regimen is inferior to atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in terms of efficacy and safety according to phase 3 data and the recently published 3 network meta-analysis [82–84]. Therefore, STRIDE regimen is indicated for patients who are unsuitable for bevacizumab [85–88] (Fig. 6), and actually in the clinical practice in Japan, 70% of 1st-line agents currently used is Atezo/Bev followed by lenvatinib (15%), STRIDE (10%), and durvalumab monotherapy (5%) (Fig. 6) although the JSH systemic therapy algorithm suggests that the two regimens are equally recommended because there is no direct comparison between the 2 regimens (Fig. 7) [23]. Durvalumab monotherapy may be indicated for patients with Child-Pugh score 7 or 8 liver function since ICI monotherapy showed good efficacy and safety in patients with Child-Pugh score 7 and 8 liver function similar to those with Child-Pugh A liver function in the CheckMate 040 [89] study and in the meta-analysis [90].

Fig. 6.

1st-line systemic treatment algorithm currently conducted in practice in Japan for advanced-stage HCC.

Fig. 7.

Systemic treatment algorithm for unresectable HCC established by Japan Society of Hepatology (cited from Hasegawa et al. [23]).

Combination Treatment with TACE and Systemic Therapy in Advanced HCC

The results of the LAUNCH trial of LEN-TACE versus LEN for advanced HCC showed that LEN-TACE is superior to LEN regarding OS and PFS [46] (OS HR, 0.45; PFS HR, 0.43). This result is reasonable because intrahepatic lesions often determine the prognosis of patients with advanced HCC. The control of intrahepatic lesions by LEN-TACE significantly prolongs survival compared with LEN alone. The IMPACT trial (iRCTs051230037), a phase 3 trial of Atezo/Bev plus TACE versus Atezo/Bev alone, is currently ongoing in Japan (Fig. 3).

Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy

HAIC was developed in Japan and is now actively used predominantly in Asian countries and rarely outside Asia. In Japan, several regimens are used including low-dose 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus cisplatin (CDDP) (FP) [91], New FP, or one-shot infusion of CDDP [92]. The role of HAIC in the treatment of HCC was evaluated in a subanalysis of the SILIUS trial [93, 94]. The efficacy of HAIC compared with sorafenib was demonstrated using propensity score matching by Ueshima, Ogasawara et al. [91], and in prospective RCT by He et al. [95]. Systemic therapy and HAIC have different indications in the following settings: (1) HAIC is mainly indicated for HCC with major vascular invasion, including Vp3 or Vp4; (2) systemic therapies such as Atezo/Bev, Durva/Treme, or LEN are recommended only for Child-Pugh A patients with multiple nodules in both lobes; and (3) durvalumab monotherapy or HAIC are both options for HCCs with Child-Pugh B liver function in Japan (Fig. 2, 6) [89, 91].

Radiation, Proton Beam, and Heavy Particle Beam Therapy

Stereotactic body radiation therapy is used for the treatment of HCC, especially in cases of portal vein tumor invasion. In April 2022, proton beam and heavy particle beam therapies were approved by insurance coverage for the treatment of HCCs with a diameter of ≥4 cm and are expected to be actively used for curative purposes in the future.

Current Status of Treatment for Terminal Stage HCC (BCLC-D)

Child-Pugh C HCC is considered a terminal stage, and the JSH clinical practice guidelines (Fig. 2) recommend transplantation if the tumor burden is small or best supportive care if the tumor burden is large. For liver transplantation, the 5-5-500 criteria, which is defined as tumor status up to 5 nodules with a maximum diameter of 5 cm and AFP value of 500 ng/mL or less were approved by insurance coverage in April 2020 [96, 97] in addition to the Milan criteria [98] and included in the 2021 edition of the JSH Clinical Practice Guidelines for HCC (Fig. 2) [23]. This revision was made because both living and brain-death donor liver transplants are currently covered by insurance in cases of tumor burden within the Milan and the 5-5-500 criteria.

Conclusion

This editorial summarizes the most updated clinical practice being conducted in Japan in the treatment of HCC with emphasis on the latest advances. Many clinical trials evaluating the treatment of HCC at different stages are ongoing (Fig. 3); the results of these trials will undoubtedly change the treatment paradigm for HCC and contribute to improving the prognosis in all stages of HCC patients.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Lecture: Eli Lilly, Bayer, Eisai, Chugai, Takeda, AstraZeneca; Grants: Taiho, Otsuka, EA Pharma, AbbVie, Eisai, Chugai, GE Healthcare; Advisory consulting: Chugai, Roche, AstraZeneca, Eisai. Masatoshi Kudo is the Editor-in-Chief of Liver Cancer.

Funding Sources

There is no funding for this Editorial.

Author Contributions

Masatoshi Kudo conceived, wrote, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

There is no funding for this Editorial.

References

- 1. Kudo M. Surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: 2021 update. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(3):167–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kudo M, Izumi N, Kokudo N, Sakamoto M, Shiina S, Takayama T, et al. Report of the 21st nationwide follow-up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan (2010-2011). Hepatol Res. 2021;51(4):355–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kudo M, Izumi N, Kokudo N, Sakamoto M, Shiina S, Takayama T, et al. Report of the 22nd nationwide follow-up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan (2012-2013). Hepatol Res. 2022;52(1):5–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iijima H, Kudo M, Kubo S, Kurosaki M, Sakamoto M, Shiina S, et al. Report of the 23rd nationwide follow-up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan (2014-2015). Hepatol Res. 2023;53(10):895–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan . Report of the 24th Nationwide follow-up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan (2016-2017) Osaka; 2022. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kudo M. Surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: 2023 update. Liver Cancer. 2023;12(2):95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):282–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, Chan SL, Kelley RK, Furuse J, et al. Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evid. 2022;1(8):EVIDoa2100070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tateishi R, Uchino K, Fujiwara N, Takehara T, Okanoue T, Seike M, et al. A nationwide survey on non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: 2011-2015 update. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(4):367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takayama T, Hasegawa K, Izumi N, Kudo M, Shimada M, Yamanaka N, et al. Surgery versus radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial (SURF trial). Liver Cancer. 2022;11(3):209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243(3):321–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang J, Yan L, Cheng Z, Wu H, Du L, Wang J, et al. A randomized trial comparing radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for HCC conforming to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg. 2010;252(6):903–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feng K, Yan J, Li X, Xia F, Ma K, Wang S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57(4):794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M, Izumi N, Ichida T, Kudo M, et al. Comparison of resection and ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study based on a Japanese nationwide survey. J Hepatol. 2013;58(4):724–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Izumi N, Hasegawa K, Nishioka Y, Takayama T, Yamanaka N, Kudo M, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of surgery vs. radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma (SURF trial). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_Suppl l):4002. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kudo M, Hasegawa K, Kawaguchi Y, Takayama T, Izumi N, Yamanaka N, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of surgery vs. radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma (SURF trial): analysis of overall survival. ASCO Annual Meeting. 2021 June 4-8. (Online). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamashita T, Kawaguchi Y, Kaneko S, Takayama T, Izumi N, Yamanaka N, et al. A multicenter, non-randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of surgery versus radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma (SURF-Cohort Trial): analysis of overall survival. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_Suppl l):4095. abstract 4095.35921606 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hasegawa K, Takemura N, Yamashita T, Watadani T, Kaibori M, Kubo S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma: the Japan society of Hepatology 2021 version (5th JSH-HCC guidelines). Hepatol Res. 2023;53(5):383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kudo M, Kawamura Y, Hasegawa K, Tateishi R, Kariyama K, Shiina S, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: JSH consensus statements and recommendations 2021 update. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(3):181–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qin S, Chen M, Cheng AL, Kaseb AO, Kudo M, Lee HC, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus active surveillance in patients with resected or ablated high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave050): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01796-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kudo M. Adjuvant atezolizumab-bevacizumab after resection or ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2023;12(3):189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Nakahira S, Nishida N, Ida H, Minami Y, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) after Surgical Resection (SR) or Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) (NIVOLVE): a phase 2 prospective multicenter single-arm trial and exploratory biomarker anlysis 2021. J Clinical Oncal. 2021;39(15). Abstr #4070. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Nakahira S, Nishida N, Ida H, Minami Y, et al. Final results of adjuvant nivolumab for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) after Surgical Resection (SR) or Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) (NIVOLVE): a phase 2 prospective multicenter single-arm trial and exploratory biomarker analysis. J Clinical Oncal. 2022;40(4). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kudo M. Adjuvant immunotherapy after curative treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(5):399–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, Chau GY, Yang J, Kudo M, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. European Association for the Study of the Liver Electronic address easloffice@easlofficeeuEuropean Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kudo M, Izumi N, Kokudo N, Matsui O, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: consensus-based clinical practice guidelines proposed by the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) 2010 updated version. Dig Dis. 2011;29(3):339–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kudo M, Matsui O, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Okusaka T, Miyayama S, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization failure/refractoriness: JSH-LCSGJ criteria 2014 update. Oncology. 2014;87(Suppl 1):22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raoul JL, Gilabert M, Piana G. How to define transarterial chemoembolization failure or refractoriness: a European perspective. Liver Cancer. 2014;3(2):119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vogel A, Cervantes A, Chau I, Daniele B, Llovet JM, Meyer T, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 4):iv238–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Surveillance group; Diagnosis group; Staging group; Surgery group; Local ablation group; TACE/TARE/HAI group, et al. Management consensus guideline for hepatocellular carcinoma: 2016 updated by the taiwan liver cancer association and the gastroenterological society of taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117(5):381–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheng AL, Amarapurkar D, Chao Y, Chen PJ, Geschwind JF, Goh KL, et al. Re-evaluating transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: consensus recommendations and review by an International Expert Panel. Liver Int. 2014;34(2):174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, Kanogawa N, Motoyama T, Suzuki E, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib in intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients refractory to transarterial chemoembolization. Oncology. 2014;87(6):330–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arizumi T, Ueshima K, Chishina H, Kono M, Takita M, Kitai S, et al. Validation of the criteria of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization failure or refractoriness in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma proposed by the LCSGJ. Oncology. 2014;87(Suppl 1):32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peck-Radosavljevic M, Kudo M, Raoul J, Lee H, Decaens T, Heo J, et al. Outcomes of Patients (pts) with Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) treated with Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE): global OPTIMIS final analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(Suppl l):abstr 4018. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kudo M, Han KH, Ye SL, Zhou J, Huang YH, Lin SM, et al. A changing paradigm for the treatment of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: asia-pacific primary liver cancer Expert consensus statements. Liver Cancer. 2020;9(3):245–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Chan S, Minami T, Chishina H, Aoki T, et al. Lenvatinib as an initial treatment in patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma beyond up-to-seven criteria and child-pugh A liver function: a proof-of-concept study. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(8):1084. 10.3390/cancers11081084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kudo M. A new treatment option for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma with high tumor burden: initial lenvatinib therapy with subsequent selective TACE. Liver Cancer. 2019;8(5):299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fu Z, Li X, Zhong J, Chen X, Cao K, Ding N, et al. Lenvatinib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization for treatment of unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (uHCC): a retrospective controlled study. Hepatol Int. 2021;15(3):663–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peng Z, Fan W, Zhu B, Wang G, Sun J, Xiao C, et al. Lenvatinib combined with transarterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III, randomized clinical trial (LAUNCH). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(1):117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307(5706):58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kudo M, Imanaka K, Chida N, Nakachi K, Tak WY, Takayama T, et al. Phase III study of sorafenib after transarterial chemoembolisation in Japanese and Korean patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(14):2117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lencioni R, Llovet JM, Han G, Tak WY, Yang J, Guglielmi A, et al. Sorafenib or placebo plus TACE with doxorubicin-eluting beads for intermediate stage HCC: the SPACE trial. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1090–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Meyer T, Fox R, Ma YT, Ross PJ, James MW, Sturgess R, et al. Sorafenib in combination with transarterial chemoembolisation in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (TACE 2): a randomised placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(8):565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Ikeda M, Torimura T, Tanabe N, Aikata H, et al. Randomised, multicentre prospective trial of Transarterial Chemoembolisation (TACE) plus sorafenib as compared with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial. Gut. 2020;69(8):1492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kudo M, Han G, Finn RS, Poon RT, Blanc JF, Yan L, et al. Brivanib as adjuvant therapy to transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized phase III trial. Hepatology. 2014;60(5):1697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kudo M, Cheng AL, Park JW, Park JH, Liang PC, Hidaka H, et al. Orantinib versus placebo combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENTAL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(1):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Ikeda M, Torimura T, Tanabe N, Aikata H, et al. Final results of TACTICS: a randomized, prospective trial comparing transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib to transarterial chemoembolization alone in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(4):354–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kudo M. Implications of the TACTICS trial: establishing the new concept of combination/sequential systemic therapy and transarterial chemoembolization to achieve synergistic effects. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(6):487–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Marrero JA, Schwartz M, Meyer T, Galle PR, et al. Trial design and endpoints in hepatocellular carcinoma: AASLD consensus conference. Hepatology. 2021;73(Suppl 1):158–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Llovet JM, Montal R, Villanueva A. Randomized trials and endpoints in advanced HCC: role of PFS as a surrogate of survival. J Hepatol. 2019;70(6):1262–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Terashima T, Yamashita T, Takata N, Nakagawa H, Toyama T, Arai K, et al. Post-progression survival and progression-free survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated by sorafenib. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(7):650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kudo M, Montal R, Finn RS, Castet F, Ueshima K, Nishida N, et al. Objective response predicts survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with systemic therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(16):3443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Cheng AL, et al. Overall survival and objective response in advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a subanalysis of the REFLECT study. J Hepatol. 2023;78(1):133–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Singal AG, Kudo M, Bruix J. Breakthroughs in hepatocellular carcinoma therapies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(8):2135–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kudo M. New treatment paradigm with systemic therapy in intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27(7):1110–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kudo M. Extremely high objective response rate of lenvatinib: its clinical relevance and changing the treatment paradigm in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2018;7(3):215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yamashita T, Kudo M, Ikeda K, Izumi N, Tateishi R, Ikeda M, et al. REFLECT-a phase 3 trial comparing efficacy and safety of lenvatinib to sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: an analysis of Japanese subset. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(1):113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ueshima K, Nishida N, Hagiwara S, Aoki T, Minami T, Chishina H, et al. Impact of baseline ALBI grade on the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with lenvatinib: a multicenter study. Cancers. 2019;11(7):952. 10.3390/cancers11070952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kuroda H, Oikawa T, Ninomiya M, Fujita M, Abe K, Okumoto K, et al. Objective response by mRECIST to initial lenvatinib therapy is an independent factor contributing to deep response in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib-transcatheter arterial chemoembolization sequential therapy. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(4):383–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Saeki I, Ishikawa T, Inaba Y, Morimoto N, et al. A phase 2, prospective, multicenter, single-arm trial of transarterial chemoembolization therapy in combination strategy with lenvatinib in patients with unresectable intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS-L trial. Liver Cancer. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68. Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, Mehta N, Heimbach JK, Dawson LA, et al. AASLD practice guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vogel A, Martinelli E, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Updated treatment recommendations for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) from the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(6):801–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76(3):681–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cheng A-L, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim T-Y, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kudo M, Finn RS, Galle PR, Zhu AX, Ducreux M, Cheng AL, Ikeda M, et al. IMbrave150: efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients with barcelona clinic liver cancer stage B unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: an exploratory analysis of the phase III study. Liver Cancer. 2023;12(3):238–250. 10.1159/000528272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kudo M, Aoki T, Ueshima K, Tsuchiya K, Morita M, Chishina H, et al. Achievement of complete response and drug-free status by atezolizumab plus bevacizumab combined with or without curative conversion in patients with transarterial chemoembolization-unsuitable, intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter proof-of-concept study. Liver Cancer. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74. Kudo M. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab followed by Curative conversion (ABC conversion) in patients with unresectable, TACE-unsuitable intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver cancer. 2022;11(5):399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kudo M. A novel treatment strategy for patients with intermediate-stage HCC who are not suitable for TACE: upfront systemic therapy followed by curative conversion. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(6):539–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kudo M. All stages of HCC patients benefit from systemi therapy combined with locoregional therapy. Liver Cancer. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77. Kudo M. Drug-off criteria in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who achieved clinical complete response after combination treatment with immunotherapy and locoregional therapy. Liver Cancer. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78. Kudo M, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Zhu AX, Ducreux M, Galle PR, et al. Albumin-bilirubin grade analyses of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a post hoc analysis of the phase III IMbrave150 study. Liver Cancer. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79. Cabibbo G, Reig M, Celsa C, Torres F, Battaglia S, Enea M, et al. First-line immune checkpoint inhibitor-based sequential therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for future trials. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(1):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Abou-Alfa GK, Chan SL, Kudo M, Lau G, Kelley RK, Furuse J, et al. Phase 3 randomized, open-label, multicenter study of Tremelimumab (T) and Durvalumab (D) as first-line therapy in Patients (pts) with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (uHCC): HIMALAYA. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(4_Suppl l):379. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kudo M. Durvalumab plus tremelimumab: a novel combination immunotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(2):87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhang B, Tao B, Li Y, Yi C, Lin Z, Ma Y, et al. Dual immune checkpoint inhibitors or combined with anti-VEGF agents in advanced, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Intern Med. 2023;111:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fulgenzi CAM, Scheiner B, Korolewicz J, Stikas CV, Gennari A, Vincenzi B, et al. Efficacy and safety of frontline systemic therapy for advanced HCC: a network meta-analysis of landmark phase III trials. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Celsa C, Cabibbo G, Pinato DJ, Maria GD, Enea M, Vaccaro M, et al. Balancing efficacy and tolerability of first-line systemic therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a network metanalysis. Liver Cancer. 2023. Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85. Kudo M. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2023;12(2):256–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, et al. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(3):151–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bejjani AC, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma: pick the winner-tyrosine kinase inhibitor versus immuno-oncology agent-based combinations. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(24):2763–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kudo M. Prioritized requirements for first-line systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: broad benefit with less toxicity. Liver Cancer. 2023;12:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kudo M, Matilla A, Santoro A, Melero I, Gracián AC, Acosta-Rivera M, et al. CheckMate 040 cohort 5: a phase I/II study of nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh B cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;75(3):600–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. El Hajra I, Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M, Sapena V, Muñoz-Martínez S, Mauro E, Llarch N, et al. Outcome of patients with HCC and liver dysfunction under immunotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2023;77(4):1139–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ueshima K, Ogasawara S, Ikeda M, Yasui Y, Terashima T, Yamashita T, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2020;9(5):583–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ueshima K, Komemushi A, Aramaki T, Iwamoto H, Obi S, Sato Y, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with a port system proposed by the Japanese society of interventional radiology and Japanese society of implantable port assisted treatment. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(5):407–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Yokosuka O, Ogasawara S, Obi S, Izumi N, et al. Sorafenib plus low-dose cisplatin and fluorouracil hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus sorafenib alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (SILIUS): a randomised, open label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(6):424–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Chiba Y, Ogasawara S, Obi S, Izumi N, et al. Objective response by mRECIST is an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib in the SILIUS trial. Liver Cancer. 2019;8(6):505–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. He M, Li Q, Zou R, Shen J, Fang W, Tan G, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin vs sorafenib alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):953–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ichida A, Akamatsu N, Hasegawa K. Validation of novel Japanese indication criteria and biomarkers among living donor liver transplantation recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a single center retrospective study. Hepatoma Res. 2020;2020:54. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Shimamura T, Akamatsu N, Fujiyoshi M, Kawaguchi A, Morita S, Kawasaki S, et al. Expanded living-donor liver transplantation criteria for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma based on the Japanese nationwide survey: the 5-5-500 rule–a retrospective study. Transpl Int. 2019;32(4):356–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(11):693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]