Abstract

Introduction

Plica neuropathica (PN) is a rare, acquired, and irreversible condition characterized by the formation of a compacted mass of tangled hair held together by a hard keratin cement.

Case Presentation

In case 1, a 50-year-old woman with history of contact dermatitis of the scalp presented with hair tangling and difficulty combing. Physical examination revealed a matted mass of hair with a dirty appearance and non-scarring alopecia. Case 2 involved a 46-year-old woman who experienced spontaneous hair matting after using various products, resulting in a dreadlock-like appearance. Clinical examination showed a compact and matted mass of hair with irregular twists, dirt, and yellowish exudate.

Conclusion

PN’s exact pathogenesis is not fully understood, but it is believed to involve physical and chemical insults to the hair shaft. Risk factors include self-neglect, hair felting or rubbing, certain substances, religious practices, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs, infections, and contact dermatitis. Trichoscopy can provide valuable clues for an accurate diagnosis, such as fractured hairs, bent hair shafts, trichorrhexis nodosa, retained telogen hairs, and twisted hairs. Treatment involves cutting the matted hair, and early-stage manual separation may be beneficial.

Keywords: Plica neuropathica, Plica polonica, Bird’s nets, Alopecia, Scalp diseases, Neurodermatology

Established Facts

-

•

Plica neuropathica (PN) is a rare, acquired, and irreversible condition characterized by the formation of a compacted mass of tangled hair held together by a hard keratin cement.

-

•

Known risk factors for PN include self-neglect, felting or rubbing of the hair, exposure to certain chemicals and substances, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs, infections, and contact dermatitis.

Novel Insights

-

•

PN can be secondary to cosmetic use, with certain products implicated in its development. In some cases of PN, there is no identifiable or known risk factor associated with its occurrence.

-

•

Trichoscopy may provide valuable clues for an accurate diagnosis, such as fractured hairs and bent hair shafts.

Introduction

Plica neuropathica (PN), commonly known as bird’s nest hair or plica polonica, is a rare, acquired, and irreversible condition characterized by the formation of a compacted mass of tangled hair exhibiting irregular twisting and plaits held together by a hard keratin cement [1]. Although initially described in association with psychiatric disorders, PN has been increasingly recognized in individuals without underlying psychiatric conditions. Herein, we report two compelling cases of PN in Hispanic women, highlighting the diverse presentations and clinical aspects of this intriguing condition.

Case 1

A 50-year-old woman presented to our trichology clinic with complaints of hair tangling and difficulty combing. She had a history of contact dermatitis of the scalp, which was secondary to the use of hair dye. Additionally, she had been using calcium acetate and aluminum sulfate powders for 2 weeks, leading to progressive matting of her hair. Physical examination revealed a matted mass of hair with a dirty appearance, along with areas of non-scarring alopecia in the occipital region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Matted mass of hair tangling with a dirty appearance (a, b). Areas of non-scarring alopecia on the occipital area (c).

Case 2

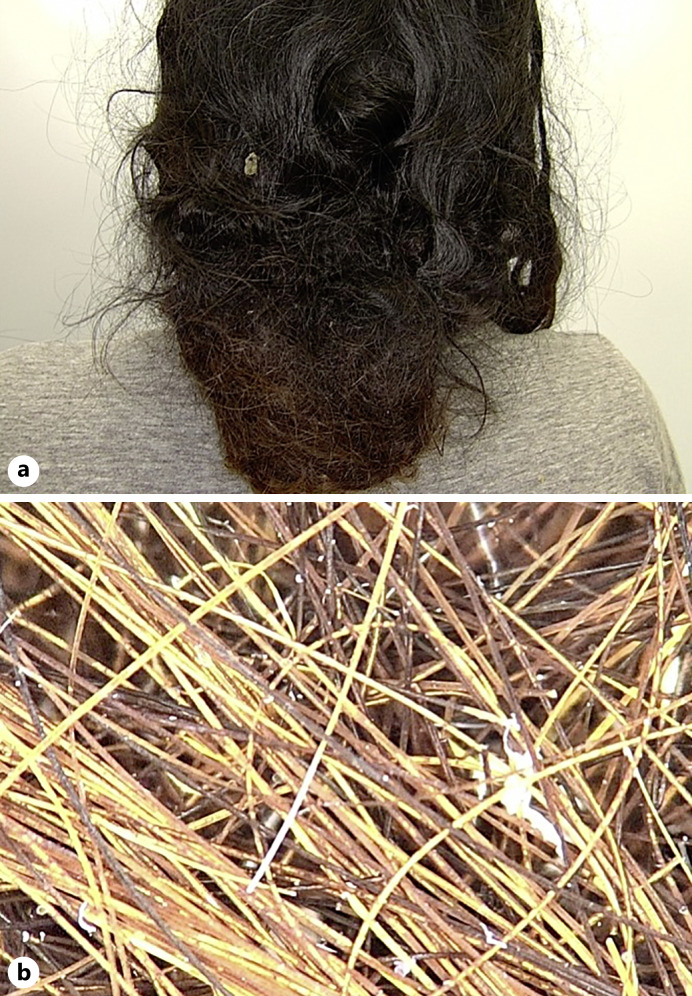

A 46-year-old female presented with spontaneous hair matting after applying several products to her scalp for unknown reasons, including coconut oil, palo pichi, and royal jelly. The day after applying these products, she noticed her hair had taken on a dreadlock-like appearance. Despite using a salicylic acid and dimethicone shampoo and conditioner, as well as a dreadlock removal shampoo, there was no improvement. Upon clinical examination, we observed a compact and matted mass of hair with irregular twists, dirt, and yellowish exudate. Trichoscopy of the hair mass revealed dry hair shafts with thick superficial yellowish scales and trichorrhexis nodosa (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Compact and matted mass of hair with irregular twists, dirt, and yellowish exudate (a). Dry hair shafts with thick superficial yellowish scales and trichorrhexis nodosa (b).

Discussion

PN was first described in 1884 by Le Page in a young female with hysteria. The exact pathogenesis of PN is not yet completely understood; however, it is believed to be associated with physical and chemical insults to the hair shaft. Known risk factors for PN include self-neglect, felting or rubbing of the hair, cationic surfactants, certain religious practices (such as Sadhu), chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs, infections, and contact dermatitis, among others [2, 3]. PN has also been reported secondary to seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis [4, 5]. Electrostatic attraction between the hair strands, triggered by these risk factors, leads to matting and irreversible damage [6]. Certain cosmetics have been associated with PN, including the use of harsh shampoos, cationic surfactants, as well as certain hairdressing and hairstyle practices [7]. Severe contact dermatitis resulting from exposure to Croton tiglium has been documented as a cause of acute hair matting [8]. In addition, a single case of PN has been reported following the use of a shampoo containing canthelin [9]. Clinically, PN presents as a compact and impenetrable mass of scalp hair with irregular twists, held together by dirt and exudate. Trichoscopy can provide valuable clues for an accurate diagnosis, such as fractured hairs, bent hair shafts, trichorrhexis nodosa, retained telogen hairs, and twisted hairs [10]. Additionally, honey-colored concretions resembling a “tangled mesh of wires” have been described [11]. Electron microscopy reveals a dense tangle with twisted hair stems, hairpin-like structures, trichoschisis, and flat ribbon-like hair.

Distinguishing PN from other hair conditions may be challenging and can be aided by a comprehensive evaluation that includes a detailed history with careful attention regarding risk factors, clinical examination, and trichoscopy. In cases of PN secondary to cosmetics, it is often possible to identify the presence of a specific product on the hair and/or scalp. Differential diagnoses should include dreadlocks. Treatment of PN involves cutting the matted hair, and in the early stages, manual separation with gentle oils may be helpful [12]. Prevention plays a crucial role and includes regular cleansing with mild shampoos, the use of conditioner, periodic hair trimming, and avoiding known risk factors.

Conclusions

PN represents an acquired hair condition characterized by irreversible damage to the hair fibers due to physical and chemical insults, leading to the formation of agglomerated hair shafts. While PN is often associated with psychiatric disorders, it can also occur in individuals without such conditions. Diagnosis primarily relies on a thorough clinical examination, with trichoscopy serving as a helpful diagnostic tool. The definitive treatment for PN remains the removal of the affected hair. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying pathogenesis and explore potential preventive strategies for this intriguing hair disorder.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local or national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

No funding was received from any source during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Daniel Asz-Sigall and César Ramos-Cavazos wrote the original draft in support with Paulina Mariel Gay-Muñoz. Jessica González-Gutiérrez ensured scientific accuracy of the paper. Alejandra Guerrero-Álvarez and Eduardo Corona-Rodarte were responsible for the design and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approve the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding Statement

No funding was received from any source during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Kumar S, Brar BK, Kapoor P. Drug-associated plica polonica: an unusual presentation. Int J Trichology. 2019 Mar-Apr;11(2):80–1. 10.4103/ijt.ijt_4_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anisha S, Sukhjot K, Sunil GK, Sandeep P. Bird’s nest view from a dermatologist’s eye. Int J Trichology. 2016 Jan-Mar;8(1):1–4. 10.4103/0974-7753.179393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kwinter J, Weinstein M. Plica neuropathica: novel presentation of a rare disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(6):790–2. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Osorio C, Fernandes K, Guedes J, Aguiar F, Silva Filho N, Lima RB, et al. Plica polonica secondary to seborrheic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Nov;30(11):e134–e135. 10.1111/jdv.13411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brar BK, Mahajan B, Kamra N. Felted hair in rupoid psoriasis: a rare association. Int J Trichology. 2014 Apr;6(2):69–70. 10.4103/0974-7753.138592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patel DR, Tandel JJ, Nair PA. Plica neuropathica: bird’s nest under dermatoscope. Int J Trichology. 2022 May-Jun;14(3):109–11. 10.4103/ijt.ijt_156_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agarwal S, Vijay A, Sharma MK, Jain AK. Alopecia areata complicated by plica neuropathica: a rare case report. Int J Trichology. 2022 Sep-Oct;14(5):183–5. 10.4103/ijt.ijt_10_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martins SS, Abraham LS, Doche I, Piraccini BM, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Acute hair matting: case report and trichoscopy findings. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):e163–4. 10.1111/jdv.13951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shah FY, Batool S, Keen A, Shah IH. Plica polonica following use of homeopathic antidandruff shampoo containing canthalin. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jan-Feb;9(1):71–2. 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_37_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Setó-Torrent N, Iglesias-Sancho M, Sola-Casas MDLÁ, Salleras-Redonnet M. Plica neuropathica in severe reactive depression: clinical and trichoscopic features. Dermatol Online J. 2021 May 15;27(5). 10.5070/D327553624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palwade PK, Malik AA. Plica neuropathica: different etiologies in 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008 Nov-Dec;74(6):655–6. 10.4103/0378-6323.45118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siragusa M, Giusto S, Ferri R, Centofanti A, Schepis C. Plica neuropathica (matting hair) in an autistic patient. J Dermatol. 2017 Sep;44(9):e212–3. 10.1111/1346-8138.13906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.