Abstract

We have isolated a new organic hydroperoxide resistance (ohr) gene from Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli. This was done by complementation of an Escherichia coli alkyl hydroperoxide reductase mutant with an organic hydroperoxide-hypersensitive phenotype. ohr encodes a 14.5-kDa protein. Its amino acid sequence shows high homology with several proteins of unknown function. An ohr mutant was subsequently constructed, and it showed increased sensitivity to both growth-inhibitory and killing concentrations of organic hydroperoxides but not to either H2O2 or superoxide generators. No alterations in sensitivity to other oxidants or stresses were observed in the mutant. ohr had interesting expression patterns in response to low concentrations of oxidants. It was highly induced by organic hydroperoxides, weakly induced by H2O2, and not induced at all by a superoxide generator. The novel regulation pattern of ohr suggests the existence of a second organic hydroperoxide-inducible system that differs from the global peroxide regulator system, OxyR. Expression of ohr in various bacteria tested conferred increased resistance to tert-butyl hydroperoxide killing, but this was not so for wild-type Xanthomonas strains. The organic hydroperoxide hypersensitivity of ohr mutants could be fully complemented by expression of ohr or a combination of ahpC and ahpF and could be partially complemented by expression ahpC alone. The data suggested that Ohr was a new type of organic hydroperoxide detoxification protein.

Increased production of reactive oxygen species, including superoxides, H2O2, and organic hydroperoxides, is an important component of the plant defense response against microbial infection (23, 42) and is a consequence of normal aerobic metabolism (15, 16). Bacteria have evolved complex mechanisms to detoxify and repair damage caused by reactive oxygen species. For detoxification of superoxides and H2O2, the enzymes involved and the regulation of their genes are well studied (11, 12, 17). Much less is known regarding defense against organic peroxides.

Organic hydroperoxides are highly toxic molecules, partly due to their ability to generate free organic radicals, which can react with biological molecules and perpetuate free radical reactions (1, 19). Thus, genes involved in protection against organic peroxide toxicity are likely to play important roles in oxidative stress response and in host-pathogen interactions. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpR) is the only major microbial enzyme that has been shown to be involved in converting organic hydroperoxides into the corresponding alcohols (3, 21, 40).

The AhpR mechanism of action is well studied. The enzyme consists of two subunits named AhpC and AhpF (4, 5, 21, 37, 38). The genes coding for these subunits are widely distributed (3, 4). Genetic analysis of several bacteria has shown that mutations in these genes lead to an organic hydroperoxide-hypersensitive phenotype, and this confirms their roles in protecting against organic hydroperoxides (2, 40, 45). Other bacterial enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase (33), glutathione transferase (34), and peroxidases (12), can also use organic hydroperoxides as substrates with varying degrees of efficiency. However, these enzymes have not been well characterized biochemically and genetically. Also, their distribution in only certain groups of bacteria (33, 34) raises a question as to whether they play important physiological roles in the protection against organic hydroperoxide toxicity.

In this paper, we report the isolation and characterization of a possible new organic hydroperoxide detoxification enzyme with a novel regulatory pattern.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial cultures and media.

All Xanthomonas strains were grown aerobically at 28°C in SB medium as previously described (6, 35). To ensure the reproducibility of results, all experiments were performed on cultures at similar stages of growth. All Escherichia coli strains were grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C. Microaerobic growth conditions were achieved by placing the plates in an anaerobic jar with a Campylobacter gas pack (Oxoid) and incubating them at 28°C.

Nucleic acid extraction and analysis, cloning, and nucleotide sequencing.

Restriction enzyme digestions were performed according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. Molecular cloning, gel electrophoresis, and nucleic acid hybridization were performed as previously described (28). Nucleotide sequencing was done using ABI Prism dye terminator sequencing kits on an ABI 373 automated sequencer. E. coli and Xanthomonas were transformed by a chemical method (28) and by electroporation (30), respectively. Genomic DNA extraction from Xanthomonas spp. was done according to the method of Mongkolsuk et al. (30). Total RNA was isolated by a hot-phenol method (30). pUFR-ahpCF was generated by subcloning a DNA fragment containing Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli ahpCF (24) into pUFR047.

Construction of an ohr mutant.

An ohr mutant was created by marker exchange between a mutated copy of ohr and a functional genomic copy. Specifically, a tet gene from pSM-Tet (32) was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and cloned into similarly digested p18Not (10), resulting in pNot-Tet. A mutated ohr gene was then constructed by insertion of a NotI-digested tet gene from pNot-Tet into a unique NotI site located in the ohr coding region of pohr11 (Fig. 1). This resulted in a recombinant plasmid designated pohr-tet. ohr inactivation was confirmed by loss of the ability of pohr-tet to confer resistance to tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBOOH) in E. coli TA4315 (ΔahpCF [40]). The plasmid was electroporated into X. campestris pv. phaseoli, and transformants were selected on SB plates containing 20 μg of tetracycline/ml. Tetr colonies appeared after 48 h of incubation at 28°C. These colonies were picked and scored for Apr phenotype. Those transformants which were both Tetr and Aps (a double cross-over resulted in marker exchange) were selected for further characterization. Marker exchanges between the mutated ohr and the functional copy of the gene in putative mutants were confirmed by analysis of hybridization patterns of genomic DNA digested with restriction enzymes and probed with ohr.

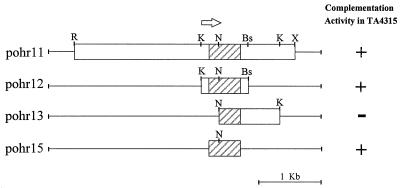

FIG. 1.

Localization of ohr. The open boxes represent X. campestris pv. phaseoli genomic DNA cloned in the indicated plasmids, and the shaded boxes represent the ohr gene. The arrow indicates the direction of ohr transcription. Bs, BstXI; K, KpnI; N, NotI; R, EcoRI; X, XbaI; +, growth of TA4315 harboring the plasmid on LB-ampicillin plates containing 100 μM tBOOH; −, no growth.

Effects of oxidants on growth and killing.

Effects of low concentrations of oxidants on Xanthomonas growth was tested with log-phase cells. Essentially, overnight cultures of late-log-phase cells were subcultured as a 5% inoculum into fresh SB medium and allowed to grow for 1 h. Oxidants were then added at appropriate concentrations, and the growth of both induced and uninduced cultures was subsequently monitored spectrophotometrically. Quantitative analysis of the killing effects of high concentrations of oxidants on various Xanthomonas strains was performed as previously described (30). Qualitative analysis of levels of resistance to various reagents was done by using a killing zone method (31). Essentially log-phase cells were mixed with SB top agar and poured onto SB plates. After the top agar had solidified, 6-mm-diameter discs containing appropriate concentrations of oxidants were placed on the cell lawn, and zones of growth inhibition were measured after 24 h of incubation at 28°C.

High-level expression and purification of Ohr for antibody production.

High levels of ohr expression for Ohr purification were achieved by using a gene fusion expression vector system in E. coli. One oligonucleotide primer corresponding to the 5′ region of ohr from the second codon (5′ TACGAATTCATGGCCTCACCC 3′) and a second primer corresponding to the ohr translation termination codon (5′ TCCAAGCTTGCATTACGCCA 3′) were used to amplify ohr from pohr15. A PCR product of 500 bp was then digested with EcoRI and HindIII, gel purified, and cloned into pMAL-C2 vector (New England Biolabs Inc.). This was expected to result in the frame fusion of ohr with maltose binding protein. Transformants with correct inserts were screened for high levels of expression of the fusion protein by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A clone designated pMalohr showed high levels of expression of the fusion protein, and it was chosen for large-scale protein purification.

A 200-ml culture of pMalohr was grown and induced with 2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 1 h. The cells were subsequently pelleted, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The suspension was then sonicated for 20 min, with cooling intervals. Ohr fusion protein was purified from crude lysate by using amylose affinity columns according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The purified fusion protein was then cleaved with protease factor Xa, and Ohr was repurified from SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Purified Ohr was used to raise antibody in rabbits.

Immunodetection of Ohr.

Crude lysates from Xanthomonas were prepared according to the method of Mongkolsuk et al. (30), and the total protein concentration was determined by the dye-binding method (2). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, blotting, blocking, and antibody reaction analysis were performed as previously described (31) except that an anti-Ohr antibody was used as a primary antibody at 1:3,000 dilution. Antibody reactions were detected by a goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Expression analysis.

A 40-ml mid-log-phase X. campestris pv. phaseoli culture was equally divided among four flasks and grown for 1 h until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.4. H2O2, tBOOH, or menadione (MD) at a 100 μM final concentration was added, and the cultures were grown for 1 h longer before both induced and uninduced cultures were harvested for Western analysis of Ohr. For analysis of ohr RNA a similar induction protocol was performed except that the induction time was reduced to 15 min. The cells were harvested as before, and total RNA was extracted by a hot-phenol method (30).

Nuclotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence accession number for ohr in GenBank is AF036166.

RESULTS

Isolation and localization of ohr.

Our objective was to isolate the Xanthomonas genes involved in organic peroxide protection by suppressing the organic hydroperoxide-hypersensitive phenotype of an E. coli ahpCF mutant. An aliquot of an X. campestris pv. phaseoli DNA library in pUC18 was electroporated into TA4315 (ΔahpCF [40]). Transformants were selected on LB-ampicillin agar containing 500 μM tBOOH and 1 mM IPTG. After 24 h of incubation, 12 colonies appeared on the plate. Plasmids were extracted from individual transformants and retransformed into TA4315, selecting for ampicillin resistance and scoring for concomitant tBOOH resistance. There were eight clones which retained tBOOH resistance. Restriction enzyme mapping and Southern analysis of plasmids purified from these colonies showed that they shared a common 1.2-kb KpnI fragment that cross-hybridized (data not shown). The plasmid, designated pohr11, that contained the longest X. campestris pv. phaseoli DNA insert (3.8 kb) was selected for further characterization. Subcloning and deletions of pohr11 were performed to localize the gene responsible for tBOOH resistance. The results are shown in Fig. 1. The gene which was able to confer organic hydroperoxide resistance upon the E. coli mutant was located on the 890-bp KpnI-BstXI fragment (Fig. 1, pohr12).

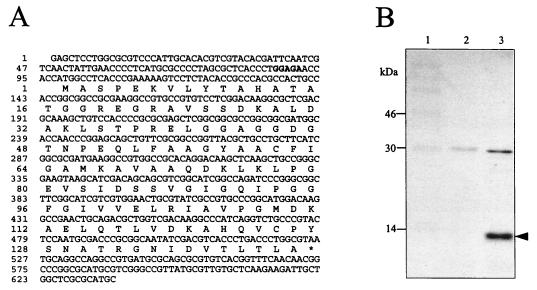

The Xanthomonas DNA in pohr11 from KpnI to BstXI was completely sequenced (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the sequence revealed many open reading frames (ORFs) in the region that could have conferred tBOOH resistance on TA4315. An ORF (designated ORF-A) with a strong ribosome binding site 6 bp upstream of a translation initiation codon and with a coding capacity for 142 amino acids having a total predicted molecular mass of 14.5 kDa was a candidate for the tBOOH resistance gene. To confirm this, primers corresponding to DNA sequences 100 bp upstream from the translation initiation codon of ORF-A (5′ GAGAATTCCTTGGCGCGGGAT 3′) and 20 bases downstream of the stop codon of ORF-A (5′ GCATCACGGCCTGGCCT 3′) were used to amplify orf-A from pohr11 in a PCR. The 560-bp PCR product was cloned into pBluescript KS, resulting in pohr15, which was transformed into TA4315. Transformants showed high levels of tBOOH resistance compared to that of TA4315 harboring the vector alone (Fig. 1). This confirmed that ORF-A was responsible for the organic hydroperoxide resistance phenotype, and it was therefore designated ohr.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence (A) and in vitro translation products (B) of ohr. (A) Nucleotide sequence and a predicted translation product of ohr. A putative ribosome binding site for ohr is shown in boldface. (B) In vitro translation of plasmid-encoded proteins with E. coli S-30 extracts. A vector control or pohr15 was added to S-30 coupled in vitro transcription-translation lysates as described in Materials and Methods. The radioactively labeled translation products are shown. Lane 1, protein molecular mass markers; lane 2, pUC18; lane 3, pohr15. The arrow indicates in vitro translation products of ohr. The second band at around 30 kDa is the product of the ampicillin resistance gene.

The coding potential for ohr was confirmed by determination of pohr15-encoded proteins by using a coupled in vitro transcription-translation E. coli system (Promega). The results (Fig. 2B) showed that pohr15 encoded a polypeptide of 14.5 kDa, identical to the calculated molecular mass of Ohr.

Sequence analysis.

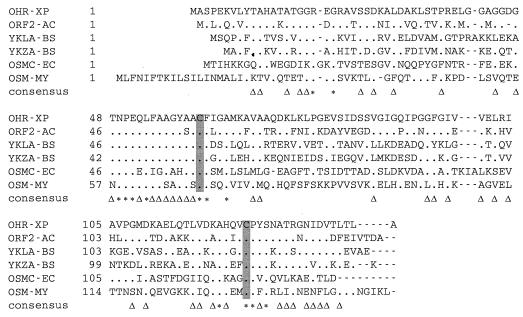

The predicted Ohr amino acid sequence had the highest homology (63%) with an unknown protein from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (36). Moderate homology (46%) with two unknown proteins (YklA and YkzA) from Bacillus subtilis was observed. There was lower homology with OsmC (an osmotic inducible protein) from E. coli (31% [18]) and an ORF of unknown function from Mycoplasma genitalium (31% [14]). The multiple alignment of these ORFs is shown in Fig. 3. It was striking that all four proteins were similar in size and had two highly conserved redox-sensitive cysteine residues, suggesting they could be important in the structure and functions of Ohr.

FIG. 3.

Multiple alignment of X. campestris pv. phaseoli Ohr (OHR-XP [AF036166]), ORF2 of Acinetobacter (ORF2-AC [Y09102]), proteins from B. subtilis (YKLA-Bs [AJ002571] and YKZA-Bs [AJ002571]), OsmC from E. coli (OSMC-EC [X57433]), and OsmC-like protein from M. genitalium (OSM-MY [U39732]). Amino acid sequences were aligned by the Clustal W program (43). Periods represent amino acids identical to those found in Ohr, asterisks indicate identical amino acids in all six sequences, and triangles represent matches of at least four amino acids in the sequences. Hyphens indicate gaps in the sequences. Conserved cysteine residues are shaded.

Structural organization and distribution of ohr.

The copy number of ohr in X. campestris pv. phaseoli was determined. X. campestris pv. phaseoli genomic DNA was individually digested with five restriction enzymes, separated, blotted, and subsequently probed with the coding region of ohr. The results showed hybridization patterns consistent with ohr being a single-copy gene (data not shown).

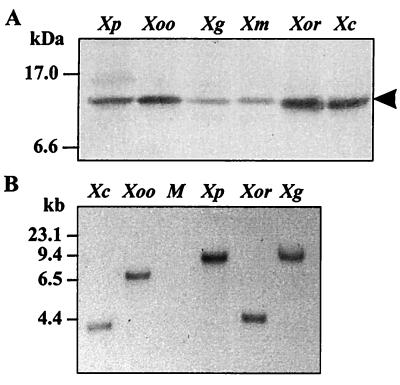

To determine the distribution of ohr in Xanthomonas and various other bacteria, both Southern and Western analysis were performed. Western blots prepared from total-protein lysates from six Xanthomonas species each showed a 14.5-kDa protein that specifically cross-reacted with an anti-Ohr antibody (Fig. 4A). In addition, genomic DNA from five Xanthomonas species was digested with a restriction enzyme, blotted, and probed with ohr. Under high-stringency washing conditions, positive hybridization signals were detected in all strains tested (Fig. 4B). By contrast, Southern blots prepared from genomic DNAs from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia did not cross-hybridize with ohr probes, even under low-stringency washing conditions. Furthermore, Western analysis of cell lysates from these bacteria did not show any proteins of a size similar to that of Ohr that specifically cross-reacted with the anti-Ohr antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Detection of Ohr and ohr in various Xanthomonas species. (A) Western analysis of Ohr in protein lysates from X. campestris pv. phaseoli (Xp), Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo), Xanthomonas campestris pv. glycine (Xg), Xanthomonas campestris pv. malvacerum (Xm), Xanthomonas oryzae pv. orizicolar (Xor), and Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (Xc). Fifty micrograms of protein was loaded into each lane. After electrophoresis, the gel was blotted onto a piece of polyvinylidene difluoride membrane that was reacted with an anti-Ohr antibody. Protein molecular mass markers are shown on the left. The arrow indicates the position of Ohr protein. (B) Southern analysis of total genomic DNA digested with EcoRI and probed with the coding region of ohr. Hybridization and high-stringency washing conditions were as previously described (30). Lane M contains DNA molecular size markers; the sizes are shown on the left.

Construction and physical characterization of a Xanthomonas ohr mutant.

The role of ohr in protecting against organic hydroperoxide toxicity in Xanthomonas was evaluated by construction of an ohr inactivation mutant, as described in Materials and Methods. Essentially, a gene conferring Tetr was inserted into the coding region of ohr and the recombinant plasmid was electroporated into X. campestris pv. phaseoli with selection for Tetr transformants that also had an Aps phenotype. Subsequently, the levels of resistance to tBOOH of these 20 Tetr Aps X. campestris pv. phaseoli transformants were tested by the killing zone method. The results showed that all putative ohr mutants were less resistant to tBOOH killing than parental X. campestris pv. phaseoli (data not shown).

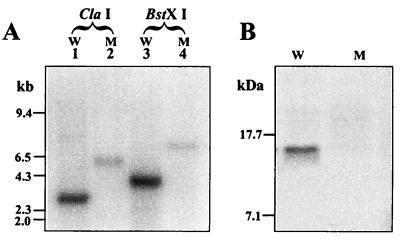

An ohr mutant designated Xp18 was selected for detailed structural analysis. The results of Southern analysis of Xp18 DNA digested with restriction enzymes and probed with ohr are shown in Fig. 5. Hybridization of the ohr probe with X. campestris pv. phaseoli or Xp18 DNA digested with either BstXI or ClaI showed that the positively hybridized bands in Xp18 were around 3 kb larger than a corresponding band detected in similarly digested X. campestris pv. phaseoli DNA (Fig. 5A). The size increase corresponded to the size of the inserted tet gene. There were no additional positively hybridized signals in digested Xp18 DNA. These results indicated that the mutated ohr had replaced the functional gene. Inactivation of ohr in Xp18 was also confirmed at the protein level by Western blot analysis with an anti-Ohr antibody. The results (Fig. 5B) showed that the Ohr protein was absent from Xp18.

FIG. 5.

Characterization of an ohr mutant at DNA (A) and protein (B) levels. (A) X. campestris pv. phaseoli (W; lanes 1 and 3) and X. campestris pv. phaseoli ohr mutant (M; lanes 2 and 4) genomic DNAs were digested with ClaI (lanes 1 and 2) and BstXI (lanes 3 and 4) restriction enzymes and Southern blotted, and the membranes were probed with ohr. DNA molecular size markers are shown on the left. (B) Western analysis of X. campestris pv. phaseoli (W) and an X. campestris pv. phaseoli ohr mutant (M). The experiment was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4A and Materials and Methods. Molecular mass markers are shown on the left.

Physiological and biochemical characterization of the ohr mutant.

The availability of the ohr mutant allowed investigation of the physiological role of ohr in the Xanthomonas oxidative stress response. The effects of both oxidative and nonoxidative stress on the growth and survival of the mutant were evaluated.

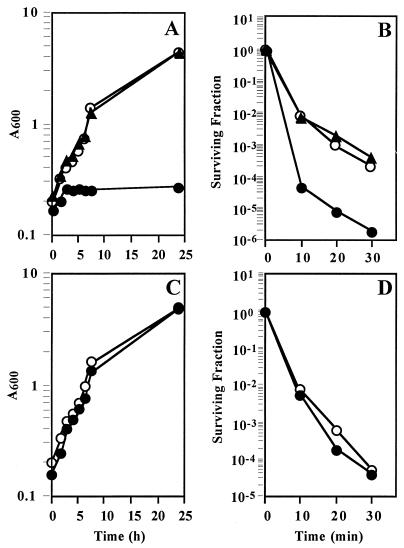

In most bacteria, the mutation of genes involved in oxidative stress protection leads to a reduced aerobic growth rate and a lower plating efficiency (26). We tested these parameters first on the ohr mutant. The mutant showed an aerobic growth rate and plating efficiency similar to those of a wild-type strain on either rich or minimal media (data not shown). Next, the effect of low oxidant concentrations on the growth rates of X. campestris pv. phaseoli and Xp18 was investigated. No differences between the growth rates of these strains were observed in the presence of several concentrations of either H2O2 or MD (data not shown). However, a low concentration of tBOOH had a significant growth-inhibitory effect on the mutant. In the presence of 600 μM tBOOH, Xp18 had a doubling time exceeding 300 min, contrasting with a 140-min doubling time for X. campestris pv. phaseoli (Fig. 6A). Cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) produced a similar growth-inhibitory effect on the mutant (data not shown). We then tested the sensitivity of the mutant to killing concentrations of tBOOH, H2O2, and MD. The quantitative results are shown in Fig. 6. The mutant was more sensitive (over 100-fold) to tBOOH killing than the wild type, but there were no differences in sensitivity to either H2O2 or MD killing. Qualitative analysis of mutant and wild-type levels of resistance to killing concentrations of other oxidants, such as diamide, N-ethylmaleimide, paraquat, and chem- ical mutagens (N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine and methyl methanesulfonate) were performed by the killing zone method. No differences in sensitivity to these agents were detected. Similarly, levels of resistance to nonoxidative stress killing agents, such as heat or pH, were identical for the two strains (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Effects of peroxides on growth and survival of X. campestris pv. phaseoli and an X. campestris pv. phaseoli ohr mutant. The effects of low concentrations of either tBOOH (600 μM) (A) or H2O2 (200 μM) (C) on the growth, or of high concentrations of tBOOH (150 mM) (B) or H2O2 (30 mM) (D) on the survival, of X. campestris pv. phaseoli (○), Xp18 (•), and Xp18 containing pUFR-ohr (▴) were measured as described in Materials and Methods. The surviving fraction is defined as the number of living cells prior to a treatment divided by the number of living cells after a treatment. The experiments were done at least three times, and representative results are shown.

Mutation in genes involved in stress protection can often lead to compensatory increases in the expression of other functionally related genes (3, 39). Thus, basal levels of enzymes involved in peroxide detoxification (AhpC, catalase, glutathione transferase, and peroxidase) or in oxidative stress protection (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and superoxide dismutase) were determined in Xp18. The results showed that levels of these enzymes were not significantly different between the wild type and the mutant (data not shown).

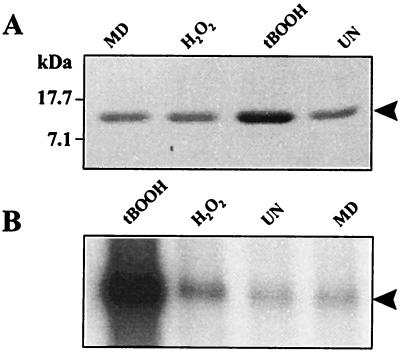

ohr expression in response to stress.

Characterization of the ohr mutant suggested that ohr played an important role in the protection of X. campestris pv. phaseoli from organic peroxide toxicity. In Xanthomonas, as in other bacteria, exposure to low levels of oxidants leads to a severalfold increase in expression of peroxide stress protective enzymes, such as catalase and AhpR (7, 31). This inducible response likely plays an important role in protecting the bacterium against stress. This knowledge prompted an investigation into the regulation of ohr in response to various oxidants. The steady-state levels of Ohr in response to oxidant treatments was determined by Western analysis. The results in Fig. 7A show a fourfold increase in the amount of Ohr after treatment with inducing concentrations of tBOOH. By contrast, only a marginal increase in Ohr was detected after exposure to H2O2 and none was detected after exposure to MD. To confirm that increased Ohr levels were due to increased ohr transcription, the amount of ohr mRNA was measured in a Northern experiment. Total RNA isolated from uninduced and tBOOH-, H2O2-, and MD-induced cultures was hybridized to ohr probes. The results are shown in Fig. 7B. Densitometer analysis of hybridization signals indicated that there was a greatly increased (15-fold) amount of ohr mRNA in response to tBOOH treatment. By contrast, there was only a minor increase (2.5-fold) after H2O2 treatments and no increase after MD treatment. The difference in ohr induction by tBOOH shown by protein and mRNA levels was likely due to the high stability of Ohr protein and its accumulation in the induced X. campestris pv. phaseoli.

FIG. 7.

Expression of ohr in response to various oxidants. (A) Western analysis of Ohr levels in X. campestris pv. phaseoli uninduced (UN) and induced with 100 μM MD, H2O2, or tBOOH was performed as described in Materials and Methods and in the legend to Fig. 4A. (B) Northern blot of total RNA isolated from X. campestris pv. phaseoli uninduced (UN) or induced with 100 μM of tBOOH, H2O2, or MD. Growth and induction conditions were the same as for panel A. Electrophoresis, blotting, hybridization, and washing were performed as previously described. The membrane was probed with radioactively labeled ohr probes. Ten micrograms of total RNA was loaded in each lane.

Increased expression of ohr in Xanthomonas species.

We have observed that in Xanthomonas increased expression of genes coding for oxidative stress protective enzymes can confer additional resistance to oxidants (24, 30). The levels of resistance of X. campestris pv. phaseoli harboring either pUFR- ohr or vector plasmids (9) to H2O2, tBOOH, and MD killing were determined. The results (Table 1) indicated that X. campestris pv. phaseoli and other Xanthomonas harboring the vector pUFR047 or pUFR-ohr had similar levels of resistance to killing concentrations of all three oxidants. Western analysis with an anti-Ohr antibody confirmed that lack of increased protection from tBOOH killing in strains harboring pUFR-ohr was not due to aberrant expression of ohr by the plasmid. In addition, the possibility that pUFR-ohr contained a defective copy of the gene was ruled out by the plasmid’s ability to complement an X. campestris pv. phaseoli ohr tBOOH-hypersensitive mutant to a wild-type level of resistance (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Summary of levels of resistance of various bacteria to oxidantsa

| Species and strain | Zone of inhibition (mm)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHP (200 mM) | tBOOH (500 mM) | H2O2 (500 mM) | |

| X. campestris pv. phaseoli/pUFR047b | 12 | 10 | 15 |

| X. campestris pv. phaseoli/pUFR-ohr | 12 | 11 | 15 |

| X. campestris pv. campestris/pUFR047 | 12 | 15 | 12 |

| X. campestris pv. campestris/pUFR-ohr | 11 | 14 | 11 |

| X. oryzae pv. oryzae/pUFR047 | 20 | 31 | 11 |

| X. oryzae pv. oryzae/pUFR-ohr | 20 | 32 | 11 |

| E. coli TA4315/pUFR047 | 28 | 30 | 12 |

| E. coli TA4315/pUFR-ohr | 12 | 15 | 12 |

| P. aeruginosa/pUFR047 | 14 | 34 | 12 |

| P. aeruginosa/pUFR-ohr | 11 | 27 | 12 |

| A. tumefaciens/pUFR047 | 24 | 23 | 20 |

| A. tumefaciens/pUFR-ohr | 19 | 20 | 21 |

Experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

pUFR047 is a broad-host-range expression vector (9).

TABLE 2.

Summary of levels of resistance of wild-type X. campestris pv. phaseoli and an ohr mutant to oxidantsa

| Strain | Zone of inhibition (mm)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHP (200 mM) | tBOOH (500 mM) | H2O2 (500 mM) | MD (500 mM) | |

| X. campestris pv. phaseoli/ pUFR047c | 12 | 10 | 15 | 10 |

| Xp18 (ohr mutant)/ pUFR047 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 11 |

| Xp18/pUFR-ohr | 12 | 11 | 15 | NDb |

| Xp18/pUFR-ahpCF | 15 | 14 | 16 | ND |

| Xp18/pahpC | 17 | 16 | 15 | ND |

| Xp18/pUFR-kat | 20 | 19 | 12 | ND |

Experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

ND, not done.

pUFR047 is a broad-host-range expression vector (9).

Heterologous expression of pUFR-ohr in various bacteria.

Unexpectedly, increased expression of ohr from an expression vector did not confer additional tBOOH resistance on various Xanthomonas strains tested (Table 1). This effect of ohr expression on tBOOH resistance was tested in various other bacteria. The broad-host-range expression vector (9) containing ohr (pUFR-ohr) was electroporated into various bacteria. The tBOOH resistance of transformants harboring pUFR-ohr was then compared to that of cells harboring the vector alone by the killing zone method. The results shown in Table 1 clearly showed that expression of ohr in E. coli K-12, P. aeruginosa, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens conferred increased resistance to tBOOH killing.

Complementation analysis of the ohr mutant.

We were interested in seeing whether increased expression of the genes involved in peroxide stress protection (those for catalase [kat] and alkyl hydroperoxide reductase [ahpCF]) or ohr could compensate for the mutant’s hypersensitivity to tBOOH killing. For this purpose, plasmids containing katX (pUFR-kat [30]), ahp C (pahpC [24]), combined ahp C and F (pUFR-ahpCF), or ohr (pUFR-ohr) were electroporated into mutant Xp18 and levels of resistance to alkyl hydroperoxides were qualitatively determined by the killing zone method. The results are shown in Table 2. As expected, pUFR-ohr, complemented the mutant’s increased sensitivity to alkyl hydroperoxide. In addition, increased expression of ahpC alone partially compensated for hypersensitivity to tBOOH killing, but the resistance achieved was still below that of the parental X. campestris pv. phaseoli strain. On the other hand, Xp18 harboring pahpCF showed resistance to tBOOH killing similar to that of wild-type X. campestris pv. phaseoli. Increased expression of katX provided no protective effect against tBOOH killing.

DISCUSSION

From X. campestris pv. phaseoli we have isolated a new gene (ohr) that is involved in organic hydroperoxide protection. An ohr mutant showed no significant growth defects under normal conditions, indicating that the gene was not essential. Important evidence from analysis of its mutant and heterologous expression suggests that Ohr plays a novel role in organic hydroperoxide metabolism. First, in many bacteria, the mutation of genes involved in oxidative stress protection always results in increased sensitivity to oxidative stress (3, 11, 12). Similarly, ohr mutants showed increased sensitivity to organic hydroperoxides. It is worth noting that the sensitivity of the ohr mutant was specific to organic hydroperoxides, unlike the mutants of other known peroxide protective (11, 12) and nonspecific DNA binding (29) genes, which often conferred increased sensitivity to several oxidants. The ability of ohr to complement the organic hydroperoxide hypersensitivity of the Xp18 mutant confirmed that the phenotype was due to a mutation in ohr. The biochemical action of Ohr is not known; its ability to increase tBOOH resistance in several unrelated bacterial species suggested that it might function directly in detoxification of organic hydroperoxides. However, we have not ruled out the possibility that Ohr is involved in the transport processes of organic molecules.

The highest degree of homology (63%) was found between Ohr and a protein of unknown function from Acinetobacter sp. (36) which is known to have metabolic pathways for n-alkane oxidation. In this bacterium, the first step in the oxidation pathway involves an attack by dioxygenase, which leads to the formation of n-alkyl hydroperoxides. These unstable intermediates are subsequently metabolized to various end products (13, 27). Thus, Ohr-like proteins in these bacteria could be involved either directly in the alkane metabolism pathway or indirectly, by providing protection against the toxic effects of alkyl hydroperoxides in a reaction similar to that of catalysis by AhpR. Some degree of homology (31%) with an unknown ORF from Mycoplasma was detected. Analysis of M. genitalium and Mycoplasma pneumoniae genome sequences surprisingly revealed a lack of known genes involved in peroxide metabolism (14, 20). This raises the question of how these bacteria protect themselves from peroxide toxicity. It is feasible that an Ohr-like protein in these bacteria could functionally substitute for AhpR and peroxidases in dealing with organic peroxides. The putative Ohr-like proteins had similar lengths and amino acid sequence motifs. This implied that they belonged to a new family of proteins involved in organic hydroperoxide metabolism.

Ohr or Ohr-like proteins as well as AhpR were found in Xanthomonas, B. subtilis, and E. coli. Both gene products seem to be involved in organic hydroperoxide detoxification. This notion was supported by the observation that expression of combined ahpC and ahpF complemented the tBOOH hypersensitivity of the Xanthomonas ohr mutant to wild-type levels. Similarly, ohr complemented the phenotype of an ahpC-ahpF E. coli mutant. Thus, there appeared to be a functional complementation between Ohr and AhpC.

Examination of the regulation of ohr expression in Xanthomonas indicated that there are at least two regulatory systems for organic hydroperoxide-inducible genes. We have shown that in one system in Xanthomonas, genes under oxyR regulation (i.e., the catalase gene and ahpC) can be induced by treatment with low concentrations of H2O2, organic hydroperoxides, or superoxide generators (7, 25, 31). The responses of ohr to peroxides and superoxide generators clearly differ, since they can be highly induced only by organic peroxides and only weakly by H2O2. In fact, the weak induction of ohr by H2O2 may be an indirect result of H2O2 reaction with membrane lipids that resulted in organic hydroperoxide production (22, 44). Thus, regulation of ohr responds to a narrower but overlapping range of inducing stresses than does the global peroxide regulator OxyR (8, 41).

Another difference between Ohr and AhpC could be related to cellular localization. Ohr has 31% homology with OsmC, a well-characterized periplasmic protein (18), while AhpC is a cytoplasmic protein. This might explain the unexpected observation that increased ohr expression in wild-type Xanthomonas did not confer resistance to higher levels of tBOOH. In wild-type Xanthomonas, transport of Ohr to the periplasmic space could be a rate-limiting step. If so, increased expression of ohr from an expression vector might not result in increased tBOOH resistance. We do not know whether OsmC is involved in organic peroxide metabolism. We are investigating this possibility.

The absence of Ohr-like protein sequences from many bacterial genome sequences in the database (e.g., those of Haemophilus influenzae and Helicobacter pylori) suggests that Ohr may perform special tasks in organic hydroperoxide detoxification for a subset of bacterial species. Indeed, these observations raise the possibility that Ohr and AhpC in Xanthomonas may have similar enzymatic functions but differ in regulation and cellular localization. The differences imply disparate physiological roles in spite of similar biochemical actions in organic hydroperoxide detoxification. Until the physiological substrates of Ohr and AhpC are known, a more definitive evaluation of their roles in organic peroxide detoxification cannot be made.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tim Flegel for critically reviewing the manuscript, G. Storz for providing E. coli strains, and J. Helmann for useful suggestions. S. Kasantsri and W. Whangsuk assisted in performing several experiments.

The work was supported by grants from Chulabhorn Research Institute, a Thai-Belgian ABOS grant, and the Thai Research Fund grant BRG 10-40. S.C. and W.P. were partially supported by graduate student training grants from NSTDA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akaike T, Sato K, Ijiri S, Miyamoto Y, Kohno M, Ando M, Maeda H. Bactericidal activity of alkyl peroxy radicals generated by heme-iron-catalyzed decomposition of organic peroxides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90136-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bsat N, Chen L, Helmann J D. Mutation of the Bacillus subtilis alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahpCF) operon reveals compensatory interactions among hydrogen peroxide stress genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6579–6586. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6579-6586.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chae H Z, Robinson K, Poole L B, Church G, Storz G, Rhee S G. Cloning and sequencing of thiol-specific antioxidant from mammalian brain: alkyl hydroperoxide reductase and thiol-specific antioxidant define a large family of antioxidant enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7017–7021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chae H Z, Uhm T B, Rhee S G. Dimerization of thiol-specific antioxidant and the essential role of cysteine 47. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7022–7026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamnongpol S, Mongkolsuk S, Vattanaviboon P, Fuangthong M. Unusual growth phase and oxygen tension regulation of oxidative stress protection enzymes, catalase and superoxide dismutase, in the phytopathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:393–396. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.393-396.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamnongpol S, Vattanaviboon P, Loprasert S, Mongkolsuk S. Atypical oxidative stress regulation of a Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae monofunctional catalase. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:541–547. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christman M F, Morgan R W, Jacobson F S, Ames B N. Positive control of a regulon for a defense against oxidative stress and some heat shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1985;41:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeFeyter R, Kado C I, Gabriel D W. Small, stable shuttle vectors for use in Xanthomonas. Gene. 1990;88:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived mini transposons. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demple B. Regulation of bacterial oxidative stress genes. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:315–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farr S B, Kogoma T. Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:561–585. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.561-585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finnerty W R. Lipids of Acinetobacter. In: Applewhite A H, editor. Proceedings of the World Conference on Biotechnology for the Fats and Oil Industry. Champaign, Ill: American Oil Chemical Society; 1988. pp. 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser C M, Gocayne J D, White O, Adams M D, Clayton R A, Fleischmann R D, Bult C J, Kerlavage A R, Sutton G, Kelley J M, Fritchman J L, Weidman J F, Small K V, Sandusky M, Fuhrmann J, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Saudek D M, Phillips C A, Merrick J M, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Bott K F, Hu P-C, Lucier T S, Peterson S N, Smith H O, Hutchison C A, Venter J C. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Flecha B, Demple B D. Metabolic sources of hydrogen peroxide in aerobically growing Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13681–13687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Flecha B, Demple B D. Homeostatic regulation of intracellular hydrogen peroxide concentration in aerobically growing Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:382–388. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.382-388.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg J T, Demple B. A global response induced in Escherichia coli by redox-cycling agents overlaps with that induced by peroxide stress. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3933–3939. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3933-3939.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez C, Devedjian C. Osmotic induction of gene osmC in Escherichia coli K12. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:959–973. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90366-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halliwell B, Gutteridge J M C. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li B-C, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson F S, Morgan R W, Christman M F, Ames B N. An alkyl hydroperoxide reductase involved in the defense of DNA against oxidative damage: purification and properties. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1488–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kappus H. A survey of chemicals inducing lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Chem Phys Lipids. 1987;45:105–115. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(87)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine A, Tenhaken R, Dixon R, Lamb C. H2O2 from oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell. 1994;79:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loprasert S, Atichartpongkun S, Whangsuk W, Mongkolsuk S. Isolation and analysis of the Xanthomonas alkyl hydroperoxide reductase gene and the peroxide sensor regulator genes ahpC and ahpF-oxyR-orfX. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3944–3949. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3944-3949.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loprasert S, Vattanaviboon P, Praituan W, Chamnongpol S, Mongkolsuk S. Regulation of oxidative stress protective enzymes, catalase and superoxide dismutase in Xanthomonas—a review. Gene. 1996;179:33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maciver I, Hansen E J. Lack of expression of the global regulator OxyR in Haemophilus influenzae has a profound effect on growth phenotype. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4618–4629. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4618-4629.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeng J H, Sakai Y, Tani Y, Kato N. Isolation and characterization of a novel oxygenase that catalyzes the first step of n-alkane oxidation in Acinetobacter sp. strain M-1. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3695–3700. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3695-3700.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez A, Kolter R. Protection of DNA during oxidative stress by the nonspecific DNA binding protein Dps. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5188–5194. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5188-5194.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mongkolsuk S, Loprasert S, Vattanaviboon P, Chanvanichayachai C, Chamnongpol S, Supsamran N. Heterologous growth phase- and temperature-dependent expression and H2O2 toxicity protection of a superoxide-inducible monofunctional catalase gene from Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3578–3584. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3578-3584.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mongkolsuk S, Loprasert S, Whangsuk W, Fuangthong M, Atichartpongkun S. Characterization of transcription organization and analysis of unique expression patterns of an alkyl hydroperoxide reductase C gene (ahpC) and the peroxide regulator operon ahpF-oxyR-orfX from Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3950–3955. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3950-3955.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mongkolsuk S, Vattanaviboon P, Rabibhadana S, Kiatpapan P. Versatile gene cassette plasmids to facilitate the construction of generalized and specialized cloning vectors. Gene. 1993;124:131–132. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90773-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore T D E, Sparling P F. Interruption of the gpxA gene increases the sensitivity of Neisseria meningitidis to paraquat. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4301–4305. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4301-4305.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishida M, Kong K H, Inoue H, Takahashi K. Molecular cloning and site directed mutagenesis of glutathione S-transferase from Escherichia coli. The conserved tyrosyl residue near the N terminus is not essential for catalysis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32536–32541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ou S H. Bacterial disease. In: Ou S H, editor. Rice disease. Tucson, Ariz: CAB International; 1987. pp. 66–96. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parche S, Geißdörfer W, Hillen W. Identification and characterization of xcpR encoding a subunit of the general secretory pathway necessary for dodecane degradation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus ADP1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4631–4634. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4631-4634.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poole L B. Flavin-dependent alkyl hydroperoxide reductase from Salmonella typhimurium. 2. Cysteine disulphides involved in catalysis of peroxide reduction. Biochemistry. 1996;35:65–75. doi: 10.1021/bi951888k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poole L B, Ellis H R. Flavin-dependent alkyl hydroperoxide reductase from Salmonella typhimurium. 1. Purification and enzymatic activities of overexpressed AhpF and AhpC proteins. Biochemistry. 1996;35:56–64. doi: 10.1021/bi951887s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherman D R, Mdluli K, Hickey M J, Arian T M, Morris S L, Barry III C E, Stiver C K. Compensatory ahpC gene expression in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1996;272:1641–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storz G, Jacobson F S, Tartaglia L A, Morgan R W, Silveira L A, Ames B N. An alkyl hydroperoxide reductase induced by oxidative stress in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli: genetic characterization and cloning of ahp. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2049–2055. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.2049-2055.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storz G, Tartaglia L A, Ames B N. Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes: direct activation by oxidation. Science. 1990;248:189–194. doi: 10.1126/science.2183352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutherland M W. The generation of oxygen radicals during host plant response to infection. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1991;39:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turton H E, Dawes I W, Grant C M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae exhibits a yAP-1-mediated adaptive response to malondialdehyde. J Bacteriol. 1977;178:1096–1101. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1096-1101.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Dhandayuthapani S, Deretic V. Molecular basis for the exquisite sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to isoniazid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13212–13216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]