Abstract

Osteoporosis and osteoporosis-related fractures in the aging population are becoming a health care problem and a burden on health service resources available. Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder that results from an imbalance in bone remodeling, leading to a reduction in bone strength with microarchitectural disruption and skeletal fragility, increasing fracture susceptibility. Osteoporosis is considered a well-known metabolic bone disorder. Although its prevalence is more commonly seen in women than men, it is eventually seen in both genders. In the elderly population, there is an increase in disability and mortality due to osteoporotic fractures.

Keywords: Remodeling, Osteoporosis signaling pathways, RANK/RANKL, Pathodynamics

Introduction

Osteoporosis and osteoporosis-related fractures in the aging population are becoming a health-care problem and a burden on health service resources available [1]. Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder that results from an imbalance in bone remodeling, leading to a reduction in bone strength with microarchitectural disruption and skeletal fragility, increasing fracture susceptibility [2]. Osteoporosis is considered a well-known metabolic bone disorder. Although its prevalence is more commonly seen in women than men, it is eventually seen in both genders. In the elderly population, there is an increase in disability and mortality due to osteoporotic fractures (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Normal bone vs Osteoporosis

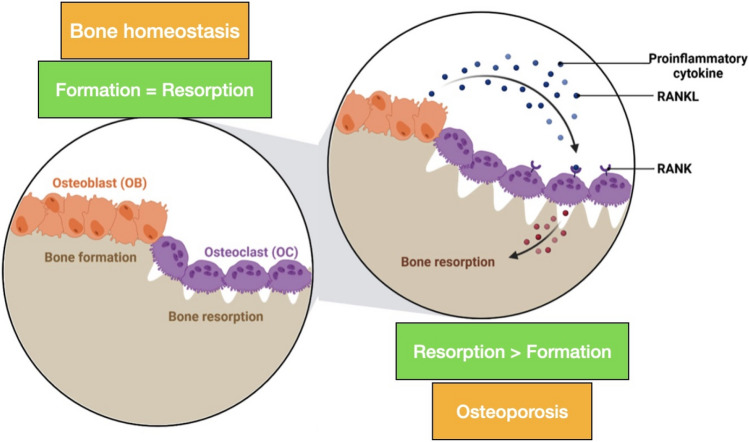

Risk Factors

Various risk factors of osteoporosis have been enumerated. These have been classified into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Non-modifiable risk factors are aging, female gender, ethnicity, and family history of osteoporosis. Aging is one of the biggest risk factors. Estrogen deficiency in females during menopause and testosterone deficiency in males cause increased bone loss. Various risk factors are enumerated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Risk factors for osteoporosis

| Non-modifiable | Modifiable |

|---|---|

| Aging | Smoking |

| Female sex | Poor calcium intake and vitamin D |

| Ethnicity | Low body weight |

| Family history of osteoporosis | Estrogen deficiency |

| Low peak bone mass | Alcohol intake |

| Low body mass index | Sedentary lifestyle |

Non-modifiable

Sex and Ethnicity

Female gender is a significant risk factor. Various studies have shown the prevalence to be higher among women as compared to men [5]. In postmenopausal women, estrogen deficiency is thought to be crucial in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. It was based on the fact that in postmenopausal women, there are naturally declining levels of estrogen, which is considered the highest risk for developing osteoporosis [6]. After a few years of menopause, there is around a 12% decline in their overall bone mass, which is equal to 1T score measured by DEXA [7]. Among ethnic races, Caucasians and Asians are more at risk than Blacks and Polynesians [8].

Aging is considered a significant risk factor for developing osteoporosis. Since each decade, there has been a 1.4–1.8 times increased risk of osteoporosis [8]. Molecular and cellular damage occurring due to ongoing age-related changes leads to the destruction of bone cells. It also causes impairment of bone remodeling. As a result, reactive oxidative species (ROS) are formed which initiates the process of osteoporosis. They are generated basically during fatty acid oxidation or in response to inflammatory cytokines. With aging, the body may not be able to protect itself from these harmful effects [7].

A family history of osteoporosis is one of the important non-modifiable factors. A positive history in the family is a strong predictor [5]. Preponderance of low body weight, recent bone loss, and history of osteoporotic fracture in the family should raise concern for osteoporosis [9].

In diabetes mellitus (DM), advanced glycation products and excessive bone marrow adipogenesis have adverse effects on bone cells and bone health. Due to impaired bone anabolic signals from insulin, Type 1 DM is associated with low BMD and contributes to the risk of osteoporotic fractures [5].

Genetic polymorphisms of genes have been studied and found to be associated with osteoporosis-related fracture risk, e.g., VDR, ER OPG, and TNFα. Some evidence of genetic predisposition is seen in individuals who have blond hair, fair skin, freckles, hypermobility, and a small build [9].

Medical Conditions

Inflammatory arthritis: inflammation occurring is pro-osteoclastogenic. Hypogonadism: sex hormone deficiency leads to impairment in bone remodeling. Chronic renal failure: characterized by dysregulation of vitamin D and calcium metabolism. Cancer: affects the bone due to bone metastasis.

Medications

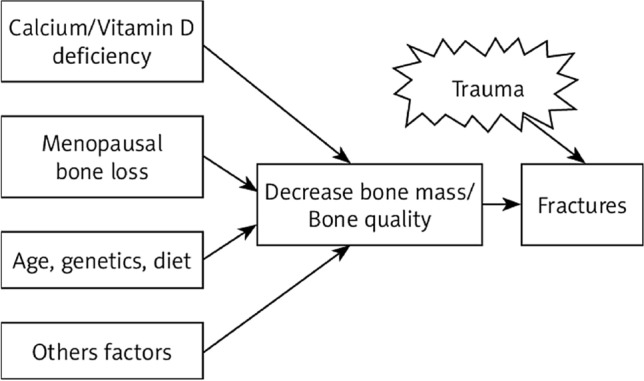

Glucocorticoid usage led to direct osteoblast apoptosis, impaired osteogenesis, stimulated osteoclasts, decreased calcium absorption from the gut, and decreased sex hormone products. Proton pump inhibitors decrease calcium absorption. Anticonvulsants affect vitamin D metabolism (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Risk factors for osteoporosis

Modifiable

Numerous modifiable risk factors of osteoporosis have been identified. Among these, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, poor calcium intake, and alcoholism have been discussed below.

Alcohol consumption Various studies have concluded that people consuming > 2 drinks/day have a relative risk of developing osteoporosis [5]. Alcoholism leads to deficient absorption of essential nutrients and vitamin D. It has also been shown to cause exocrine pancreas insufficiency with malabsorption of essential nutrients. Individuals consuming moderate or high alcohol are at higher probability for osteoporotic fractures [10].

Physical inactivity It has a positive association with osteoporosis development. It exerts mechanical load onto the bone which ultimately maintains bone mineral density (BMD) and decreases osteoporotic fracture risk [12]. Physical activity increases the amount of sex hormones. It also has a propensity to boost anti-inflammatory cytokines. It also helps in the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines which ultimately protect bone health [5].

Calcium intake It is essential for skeletal maturity during growth spurt and thus helps to achieve peak bone mass during the early age. Calcium deficiency leads to increased levels of PTH (hyperparathyroidism), which stimulates osteoclastic activity and increases reabsorption of calcium and phosphate. It also enhances calcium absorption from the GI tract and elevates serum calcium levels [5].

Vitamin D deficiency It affects intestinal calcium absorption. Low serum vitamin D levels will increase PTH levels, leading to skeletal calcium mobilization.

Low body weight Body weight puts forth mechanical load onto the bone. Having low weight affects the body’s metabolism [5]. Lean body mass (LBM) in old age gives rise to a decrease in BMD and increased risk of osteoporotic fractures [11]. A BMI of 21 kg m2 is correlated with an increased risk of low BMD. Individuals will generally achieve peak bone mass by the age of 25 years. After that, the rate of bone mass decline will begin [9]. Low BMI continues to be a risk factor for all osteoporotic fractures [10].

Cigarette smoking Chemicals released by smoking are lethal to bone metabolism. They bring changes in the RANKL pathway. It also affects calcium absorption, estrogen, and cortisol levels, and consequently enhances bone loss [5]. Nicotine leads to the inefficient absorption of nutrients, e.g., protein and calcium. In contrast to non-smokers, an increased rate of bone turnover is seen in comparison to smokers [11]. In recent meta-analyses, smoking has been correlated to an increase in the lifetime risk of developing a vertebral fracture [10] (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Low bone density increases the risk of fractures

Bone Biology and Remodeling Mechanism

Bone tissue contains dynamic, mineralized connective tissue comprising bone cells. It contributes to multiple physiological functions such as locomotion, support, and protection of soft tissues. The organic matrix assists in resisting the tensile forces and elastic forces, e.g., type 1 collagen. The inorganic matrix comprises hydroxyapatite and calcium phosphate crystals, which are accountable for bone stiffness and resist compressive forces [8]. Bone cells constitute osteocytes, osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and stem cells. Bone matrix, which is composed of calcium, phosphorus, inorganic salts, and collagen. These osteoprecursor cells further differentiate into osteoblasts and osteocytes [8].

Osteocytes are the cell types that are found abundantly. Their central role is the initiation and driving of bone remodeling. They play a crucial role in calcium and phosphate homeostasis regulation [3].

Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells and act as chief regulatory cells in bone remodeling. They are derived from the mononuclear macrophage system. Osteoblast lineage cells also regulate the differentiation of osteoclast precursors into osteoclast. After reaching bone tissue in the absorptive state, by the action of chemokines, the precursor cells further differentiate into osteoclasts led by GM-CSF and RANKL [1].

Osteoblasts are bone-forming cells. MSCs produce osteoprogenitors, which differentiate into preosteoblasts and then mature osteoblasts. These are surfacing lining cells that are accountable for the organic bone matrix formation. They also play a role in bone matrix synthesis and balancing calcium homeostasis [8].

Bone Remodeling

In bone remodeling, the keystone is a basic multicellular unit. Bone cells coordinate in the working of the bone remodeling process [7]. The bone remodeling process is stabilized by both bone formation and bone resorption phases [8].

During modeling, there is an ongoing balanced process of either bone formation or bone resorption. Thereby, changes in the dimensions and shape of bone during growth and adaptation of bone to altering mechanical demands are facilitated. A fundamental pathophysiological mechanism of more bone resorption than formation is called impaired remodeling [3].

Various intrinsic factors have been studied for their action on the signaling pathways of osteoclastogenesis. These signaling pathways regulate bone remodeling, but are yet to be fully explained.

Osteoclast Differentiation and Regulation of Bone Resorption

Mature osteoclasts surrounding the bone tissue surface release osteolysis-related enzymes for the process of bone resorption. Various elements are known to affect bone resorption, such as hormones and cytokines. They act on various signaling pathways in osteoclastogenesis. Various signaling pathways have been known, among which the RANKL and IL-1/TNF-α pathways have established mechanisms in osteoclastogenesis.

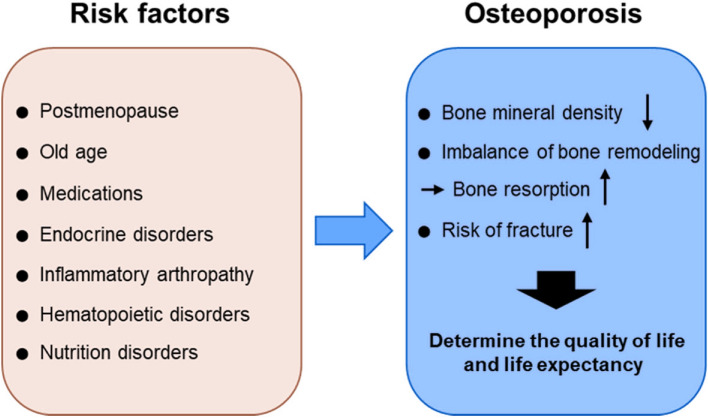

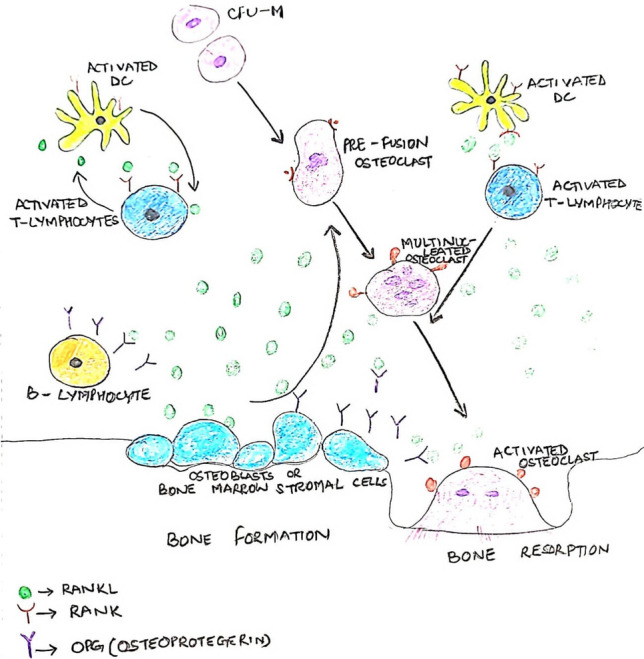

RANKL/OPG Signaling Pathway

This is the utmost important signaling pathway in the remodeling process. It has been recognized to be critical for osteoclastogenesis [1]. RANKL, RANK, and OPG belong to the TNF superfamilies. RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor Kappa B ligand) is expressed by osteoblasts and osteocytes. RANK is a RANKL-specific receptor that is found expressed in osteoclast precursors, mature osteoclasts, and immune cells. Osteoprotegerin (OPG), well known as the decoy receptor, competes with RANKL and downregulates osteoclastogenesis, as shown in Fig. 4 [2].

Fig. 4.

RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway

Osteocytes secrete RANKL, which binds to the RANK present on the surface of osteoclasts to upregulate their differentiation. Cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) indirectly regulate RANKL signaling, thus strengthening the fact that RANKL has an essential role in bone homeostasis [3].

IL‑1/TNF‑α Signaling Pathway

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) plays an important role in regulating bone homeostasis. Their inhibition can be seen as a significant clinical improvement in various chronic inflammatory joints and chronic immune diseases [13]. IL-1 induces tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) to stimulate osteoblasts to produce granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-6 and induces osteoclast precursors to differentiate into osteoclasts. TNF receptor-1 (TNFR-1) is present in osteoclast precursor cells. TNF-α will bind to TNFR-1 leading to activation of various factors promoting osteoclastogenesis [1].

Signal Pathways for Osteoblastogenesis

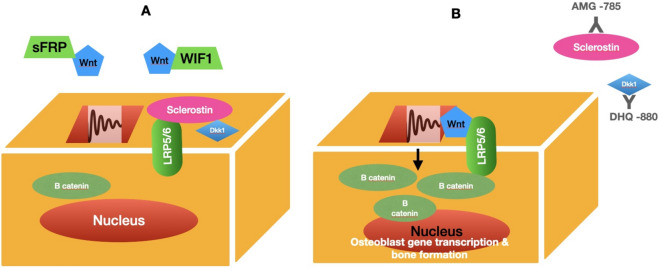

Wnt/β‑Catenin Signaling Pathway

It includes both canonical and noncanonical pathways. Canonical signaling is a fundamental pathway in bone remodeling. Wnt protein on osteoblast membrane binds to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRP5/6) and Frizzled (Fz) receptors. The stabilized β-catenin translocation leads to increased expression of bone formation genes such as OPG and RANKL [14] (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The Wnt signaling pathway

Noncanonical Pathway

Wnt Signaling Pathway (β‐Catenin‐Independent Wnt Signaling Pathway)

It activates Frizzled receptors. Hence, activates transcription factors (Jun, Spl) leading to the expression of target genes e.g., RANK in osteoclasts and Runx2 in osteoblasts [2]. This signal facilitated by G‐proteins enhances cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. It also activates calcium calmodulin‐mediated kinase II (CaMKII) and calcineurin. CaMKII suppresses the adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Calcineurin activates the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) [14].

Sclerostin (SOST)

The SOST gene has a major role in BMD regulations. Overexpression causes inhibitory effects of sclerostin on the Wnt signaling pathway [15]. The osterix and Runx2 are the main transcription factors for osteogenesis [1].

Notch Signaling Pathway

Notch is an intercellular signaling pathway system that upregulates cell differentiation. It has a dual effect on osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis, as shown in in vitro studies. Notch ligands help in promoting osteogenesis. It suppresses bone resorption by reducing sclerostin and dkk-1 signaling pathways. However, some studies have shown different roles of these ligands such that NOTCH1 inhibits and on the other hand NOTCH2 increases osteoclastogenesis [2].

Cathepsin K

Cathepsin is the most potent protease in the lysosomal protease family. They have an essential role in mediating bone resorption. It is expressed by osteoclasts. Its main function is the degradation of type I collagen and non-collagen factors (osteocalcin, proteoglycan) [2].

Pathophysiology

Several factors are elaborated in bone remodeling regulation [2]. It can be due to hormonal, paracrine, and immunological factors.

Hormonal

Low estrogen levels are contributors to postmenopausal osteoporosis. It has a critical role in maintaining bone homeostasis. Estrogen receptors are significantly seen in bone cells. Estrogen also inhibits the secretion of RANKL. It is also a promoter of growth hormone, by which they inhibit osteoclast activity. Therefore, estrogen deficiency promotes bone loss and causes osteoporosis [2]. In men, both estrogen and androgen play a role in inhibiting bone resorption [15].

Calcium and Vitamin D, Parathyroid Hormone

Bones are the reservoir of body calcium deposits. A sufficient amount of calcium intake is necessary to maintain bone mass and strength. Intake of vitamin D in an optimal amount increases intestinal calcium absorption. It binds to vitamin D receptors to upregulate bone remodeling. It can directly impact RANKL and NFATc1 signaling, although it also influences osteoclastogenesis which is promoted by various pathways, e.g., BMP-2, Runx2, and Wnt.

Low serum calcifediol levels affect serum levels of active D3 and calcium absorption, which consequently stimulates parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion. Increased PTH levels are directly related to increasing osteoclastic activity and promoting bone resorption.

Calcitonin (CT), which is secreted by the thyroid, negatively regulates calcium. It decreases calcium absorption from the intestine and increases the excretion of calcium from the kidneys, hence resulting in low blood calcium levels [2].

Deficiency of vitamin D and calcium both eventually contribute to secondary hyperparathyroidism. With increasing age, the impairment of calcium metabolism and vitamin D deficiency leads to secondary hyperparathyroidism [6]. Deranged renal function, loop diuretics, and estrogen deficiency can directly or indirectly increase PTH levels [15]. Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism are major contributors to increased bone loss. It also causes neuromuscular impairment which increases the risk of falls [6].

Cytokines, Prostaglandins, NO, and Leukotrienes

The role of cytokines such as IL-1, prostaglandins such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), nitric oxide, and leukotrienes in affecting bone health is a known old concept. These molecules work by either stimulating or inhibiting bone formation and resorption. Predominantly, PGE2 is generated by the activity of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2). It activates various factors for stimulation of bone resorption and hence enhances the effect.

NO (nitric oxide) is generated by bone cells, which enhances the production of OPG. This led to the inhibition of bone resorption. Inhibition of bone resorption by NO leads to an increase in BMD [6].

Leukotrienes In recent studies, arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase, encoded on the Alox15 human gene, was found to be a negative regulator of BMD in mice. In postmenopausal women, polymorphisms in ALOX15 has been studied to show an association of peak BMD differences [6].

Osteoimmunology

The osteoclast is the well-known prototype of an osteoimmune cell. Various studies have revealed a relationship between immune cells and osteoclasts. In rheumatoid arthritis, this interaction is a leading cause of bone destruction. Predominantly, T cells are regarded as one of the osteoimmune cells, which mediates the effect on bone. There is an accumulation of CD4+ cells in the synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis patients. They mediate the process of osteoclastogenesis by secreting IL-17 which leads to RANKL overexpression [3].

Gut Microbiome and Osteoporosis

The gut microbiome (GM) has an impact on an individual’s health. There is a role between bone metabolism and the intestinal flora, which is now well accepted. GM influences nutrient production and absorption. It also affects body growth and immune status. Various research data show that bone metabolism is affected by probiotics or antibiotics. Impaired absorption of nutrients by the gut microbiome affects bone health by decreasing BMD such as calcium.

This impairment in the bone remodeling process induces a negative impact on bone structure, especially cancellous bone. With aging, bones start becoming fragile. Various factors such as immobilization, hormonal deficiency, and nutrition imbalance have metabolic effects on bone remodeling which leads to osteopenia [8]. This structural destruction is a leading cause of deteriorating bone strength and enhancing fragility fractures [2].

Postmenopausal Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis affects mostly postmenopausal women: about 1/3–1/5 of postmenopausal women in their life will suffer an osteoporotic-related fracture and the associated morbidity, e.g., hip fractures and spine fractures. Failure to achieve peak bone density or increased bone loss following menopause are leading factors for osteoporosis.

In women, estrogen deficiency has a direct accelerating effect on bone turnover and decreases the bone density which causes structural damage of bone. This architectural damage leads to a decreased bone mass or strength and has direct impact on fragility fracture risk [4].

Senile or Age-Related Osteoporosis

The aging process results in the bone deteriorating in components, structurally or functionally.

Bone Marrow Fat

With aging, there is deposition of adipocytes in bone marrow, which directly affects the ongoing process of osteoblastogenesis. There is an increased propensity of MSCs differentiation into adipocytes. With aging, there is an overriding expression of PPARγ2 (peroxisome proliferator-activator gamma 2) for adipogenesis by MSCs with concurrent depletion in Runx2 for osteoblastogenesis expression, thereby decreasing the levels of osteoblast as compared to adipocytes [15].

Peak Bone Mass

Achieving peak bone mass significantly affects preventing osteoporosis. It also reduces the rate of subsequent osteoporotic fractures in adulthood. With an increment of 10% in bone mass, there is a 30% reduction in hip fracture. Genetic factors contribute to 80% variability in peak bone mass, e.g., LRP5, SOST, OPG, ER 1, and RANK pathway genes. However, at present, their clinical role in decision-making is under evaluation [1].

Abbreviations

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

- RANKL

Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand

- TGF

Transforming growth factor

- IGF

Insulin-like growth factor

- BMP

Bone morphogenic protein

- Hh

Hedgehog

- GM

Gut microbiome

- PTH

Parathyroid hormone

- OPG

Osteoprotegerin

- VDR

Vitamin D receptors

- ROS

Reactive oxidative species

- FZD

Frizzled

Data Availability

There is no data obtained for this report.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standard Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sandhu SK, Hampson G. The pathogenesis, diagnosis, investigation, and management of osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2011;64(12):1042–1050. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.077842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang B, Burley G, Lin S, Shi YC. Osteoporosis pathogenesis and treatment: Existing and emerging avenues. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters. 2022;27(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s11658-022-00371-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Föger-Samwald U, Dovjak P, Azizi-Semrad U, Kerschan-Schindl K, Pietschmann P. Osteoporosis: Pathophysiology and therapeutic options. EXCLI Journal. 2020;19:1017. doi: 10.17179/excli2020-2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gambacciani M, Levancini M. Hormone replacement therapy and the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Menopause Review/Przegląd Menopauzalny. 2014;13(4):213–220. doi: 10.5114/pm.2014.44996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin KY, Ng BN, Rostam MK, Muhammad Fadzil NF, Raman V, Mohamed Yunus F, Syed Hashim SA, Ekeuku SO. A mini review on osteoporosis: From biology to pharmacological management of bone loss. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11(21):6434. doi: 10.3390/jcm11216434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: Concepts, conflicts, and prospects. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(12):3318–3325. doi: 10.1172/JCI27071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armas LA, Recker RR. Pathophysiology of osteoporosis: New mechanistic insights. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics. 2012;41(3):475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aibar-Almazán A, Voltes-Martínez A, Castellote-Caballero Y, Afanador-Restrepo DF, Carcelén-Fraile MD, López-Ruiz E. Current status of the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(16):9465. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane JM, Russell L, Khan SN. Osteoporosis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2000;372:139–150. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200003000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahamsen, B., Brask-Lindemann, D., Rubin, K. H., & Schwarz, P. (2014). A review of lifestyle, smoking and other modifiable risk factors for osteoporotic fractures. Bonekey Rep.3:574. 10.1038/bonekey.2014.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wilson-Barnes SL, Lanham-New SA, Lambert H. Modifiable risk factors for bone health & fragility fractures. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2022;36(3):101758. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2022.101758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2011;28(6):121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osta B, Benedetti G, Miossec P. Classical and paradoxical effects of TNF-α on bone homeostasis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;13(5):48. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amjadi-Moheb F, Akhavan-Niaki H. Wnt signaling pathway in osteoporosis: Epigenetic regulation, interaction with other signaling pathways, and therapeutic promises. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(9):14641–14650. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demontiero O, Vidal C, Duque G. Aging and bone loss: New insights for the clinician. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 2012;4(2):61–76. doi: 10.1177/1759720X11430858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There is no data obtained for this report.