Abstract

Background:

The ketamine metabolite 2R,6R-hydroxynorketamine ((2R,6R)-HNK) has analgesic efficacy in murine models of acute, neuropathic and chronic pain. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate (AMPA) dependence of (2R,6R)-HNK analgesia and protein changes in the hippocampus in murine pain models administered (2R,6R)-HNK or saline.

Methods:

All mice were CD®−1 IGS outbred mice. Male and female mice underwent planter incision (PI) (n=60), spared nerve injury (SNI) (n=64) or tibial fracture (TF) (n=40) surgery on the left hindlimb. Mechanical allodynia was assessed using calibrated von-Frey filaments. Mice were randomized to receive saline, naloxone or the brain penetrating AMPA blocker NBQX prior to (2R,6R)-HNK 10mg/kg, and this was repeated for 3 consecutive days. The area under the paw withdrawal threshold by time curve for day 0 to 3 (AUC0–3d) was calculated using trapezoidal integration. The AUC0–3d was converted to percent antiallodynic effect using the baseline and pretreatment values as 0 and 100 percent. In separate experiments, a single dose of (2R,6R)-HNK 10 mg/kg or saline was administered to naive mice (n=20) and 2 doses to PI (n=40), SNI injury (n=40) or TF (n=40) mice. Naïve mice were tested for ambulation, rearing and motor strength. Immunoblot studies of the right hippocampal tissue were performed to evaluate the ratios of GluA1, GluA2, p-Kv2.1, pCaMKII, BDNF, p-AKT, p-ERK, CRCX4, p-EIF2SI and p-EIF4E to GAPDH.

Results:

No model specific gender difference in antiallodynic responses before (2R,6R)-HNK administration was observed. The antiallodynic AUC0–3d of (2R,6R)-HNK was decreased by NBQX but not with pretreatment with naloxone or saline. The adjusted mean (95% CI) antiallodynic effect of (2R,6R)-HNK in the PI, SNI and TF models was 40.7% (34.1%,47.3%), 55.1% (48.7%,61.5%) and 54.7% (46.5%,63.0%), greater in the SNI, difference 14.3% (95%CI 3.1 to 25.6%, P=0.007) and TF, difference 13.9% (95%CI 1.9% to 26.0%, P=0.019) compared to the PI model. No effect of (2R,6R)-HNK on ambulation, rearing or motor coordination was observed. Administration of (2R,6R)-HNK was associated with increased GluA1, GluA2, p-Kv2.1, p-CaMKII and decreased BDNF ratios in the hippocampus, with model specific variations in proteins involved in other pain pathways.

Conclusions:

(2R,6R)-HNK analgesia is AMPA dependent and (2R,6R)-HNK affected glutamate, potassium, calcium and BDNF pathways in the hippocampus. At 10mg/kg (2R,6R)-HNK demonstrated a greater antiallodynic effect in models of chronic compared with acute pain. Protein analysis in the hippocampus suggest that AMPA dependent alterations in BDNF-TrkB and Kv2.1 pathways may be involved in the antiallodynic effect of (2R,6R)-HNK.

Introduction

Ketamine has been shown to have analgesic efficacy for chronic, cancer and neuropathic pain.1,2 The effects of ketamine persist long after the drug has been cleared, suggesting a complex relationship between the drug’s binding and its clinical effects.3 Ketamine is rapidly metabolized into over twenty characterized metabolites including (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine ((2R,6R)-HNK). Preclinical studies indicate that hydroxynorketamines exert antidepressant-relevant behavioral actions and may also have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and other physiological effects useful for the treatment of a variety of human diseases.4

Zanos et al. demonstrated antidepressant behavioral actions of (2R,6R)-HNK in a murine model of depression via a mechanism involving metabotropic glutamate 2 (mGlu2) receptor signaling and activation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid receptors (AMPR) in the hippocampus resulting in increased hippocampal brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF).5,6 Ju et al demonstrated in an stress induced depression model in mice that (2R,6R)-HNK antidepressant activity was associated with an increase in hippocampal (AMPAR) subunits 1 and 2 (GluA1), (GluA2), increased BDNF, and the phosphorylated tropomyosin receptor kinase B (pTrkB)/(TrkB) ratio, suggesting that the antidepressant effect of (2R,6R)-HNK may be mediated through BDNF(TrkB) signaling.7

We have demonstrated that (2R,6R)-HNK has analgesic effects in murine pain models (plantar incision (PI), spared nerve injury (SNI), and tibial fracture (TF)).8 The analgesic efficacy of (2R,6R)-HNK in the SNI model has been replicated by Yost et al, who also demonstrated that the analgesia was AMPA and not opioid dependent.9 Jin et al examined transcriptomic changes of the BDNF/ activity regulated cytoskeleton-protein (ARC) /AMPAR axis using microarray analysis in the pre-limbic cortex in the SNI pain model.10 The finding of the study suggested that SNI associated pain was driven by increased BDNF signaling and reduced AMPAR activity and postulated that (2R,6R)-HNK analgesia was through restoration of prelimbic cortex to periaqueductal gray connectivity via decreased BDNF. No study to date has examined protein concentration changes in the hippocampus following (2R,6R)-HNK administration in murine pain models.

The purpose of this study was to extend our preclinical evaluation of (2R,6R)-HNK by assessing the anti-allodynic response of a 10 mg/kg dose of (2R,6R)-HNK in murine models of acute and chronic pain, demonstrate with pharmacological antagonists that the analgesic efficacy of (2R,6R)-HNK is AMPA dependent, and to determine if the administration of (2R,6R)-HNK in murine pain modes is associated with changes in glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunits 1 and 2 (GluA1), (GluA2), brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF), Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 (CAMK2), voltage-gated potassium channels (Kv2.1), phosphorylated extracellular signal regulated kinase 1 and 2 (p-ERK(1/2)), phosphorylated protein kinase B (p-AKT), phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 (p-EIF2S1) phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4e (p-EIF4E), p-ERK(1/2) in the hippocampus using Western Blot (WB) analysis. We hypothesize that (2R,6R)-HNK will demonstrate varying antiallodynic activity in murine pain models, that (2R,6R)-HNK analgesic behaviors will be AMPA dependent but not opioid dependent, and that hippocampal protein modulation will support the role of (2R,6R)-HNK on glutamate, potassium, Ca2+/calmodulin and BDNF pathways in the hippocampus.

Methods

Animal procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of Rush University Medical Center (IACUC Protocol ID:19–013 and 23–001) and adhered to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines and the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.11,12 The CD-1® IGS outbred mice used in this study were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Massachusetts, USA. Mice were fed a Teklad Global 18% Protein Diet (Envigo, Madison, WI) with food and water available ad libitum with 12-hour day and night cycles. Male and female mice were housed separately (4 per cage) and behavioral experiments were not performed concurrently on both species. Gender specific scent clues were minimized by cleaning the testing area and equipment with disinfectant and swabbed with isopropyl alcohol between testing sessions.

Antiallodynic Effectiveness of (2R,6R)-HNK and Pharmacological Antagonist Studies

Prior to surgery mice were tested for mechanical allodynia in the left hind paw with calibrated von Frey nylon filaments (0.028 to 5.50 g) using an iterative up-down method while standing on a grid.13 Withdrawal of the hind paw is considered a nociceptive response, with a lower force applied at withdrawal indicating greater allodynia. Normal paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) in a mouse of this age is 3 to 4 g.

Male and female mice (8 wk of age) underwent planter foot incision surgery (n=60), spared nerve injury surgery (n=64) and tibial fracture surgery (n=40). PI, SNI and TF surgeries were performed on the mouse’s left hindlimb as previously described.8 Detailed descriptions of the surgical procedures are available in Supplemental Text 1. Repeat PWT testing was performed for the PI model at 4 hours, in the SNI at 7 days, and at 21 days in the TF model. These times have been associated with reliable development of mechanical allodynic response in the models.8

Mice from each pain model type were randomly allocated to one of three treatment groups stratified by sex. Group 1 received saline (IP), group 2 received subcutaneous naloxone 1 mg/kg (Naloxone Hydrochloride Injection, USP, 4mg/10mL, Mylan, N.V., Canonsbrg, PA) and group 3 received the AMPA antagonist of (1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxobenzo [f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX) 10 mg/kg (IP) (Tocris Bioscience NBQX disodium salt, Catalog number 373, ThermoFischer Scientific, Waltham, MA). Injections volumes were 0.05 ml. Ten minutes following the first injection all groups received (2R,6R)-HNK 10 mg/kg IP.6 The (2R,6R)-HNK used in this study was synthesized in accordance to the methods reported by Zanos et al and passed all related quality control characterization methods (nuclear magnetic resonance and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry).5 The injection volume of (2R,6R)-HNK was 0.15 ml. Drug injections ((2R,6R)-HNK and antagonist) were performed on 3 consecutive days with von Frey testing 23 h after each (2R,6R)-HNK injection. The primary outcome of the pharmacological antagonist studies was the area under the PWT by time curve from day 0 to 3 (AUC0–3d).

Motor Effects in Naïve Mice

Thirty-six female naïve mice were used for measurement of spontaneous locomotor activity and motor strength. Motor strength was measure in 20 mice using the horizontal bar test.14 A 2 mm metal rod was positioned 49 cm above the bench supported by plastic columns. Mice were raised by their tail and allowed to grasp the bar at the center with their forepaws. A fall within 5 seconds was considered a failed trial and the animal was retested. A cut-off time of 30 seconds was used to limit fatigue to the mouse The average score of 3 trials was the primary outcome.15

Sixteen naïve female non-surgery mice were assessed for spontaneous activity using a clean vivarium plastic cage (42× 25× 20 cm) enclosed in a cage rack infrared photobeam activity system. One set of photobeams were placed at foot level above the cage floor (with adjacent beams 5 cm apart) to automatically measure ambulation (horizontal counts of beam interruptions when the animal walks). Another set of photobeams was placed 5 cm above the cage floor to automatically measure rearing (vertical counts of beam interruptions when the animal rears). Half of the cage was dark, and half was in the light. Animals randomly received saline (n=8) or (2R,6R)-HNK 10 mg/kg and then monitored for activity and rearing behavior in a dark room for 30 minutes. Total counts for ambulation and rearing were the primary outcome.

Evaluation of Hippocampal Protein Modulation

In another group of 20 naive male and female mice, PWT’s were assessed prior to saline (n=10) or (2R,6R)-HNK treatment and at 24 hours post drug administration. In separate experiments, male and female mice (8wk of age) underwent PI (n=40), SNI (n=40) and TF (n=40) surgery as described above. PWT’s were assessed before surgery with repeat PWT testing performed for the PI at 4 h, in the SNI at 7 days, and the TF at 28 days. Mice from the naïve as well as the 3 pain models were randomly assigned to received 10 mg/kg of (2R,6R)-HNK or saline (IP) daily. After testing at 24 h in the naïve mice and at 48 hours mice in the PI, SNI and TF model mice were euthanized following anesthesia using carbon dioxide inhalation.

Upon loss of neuronal reflexes mice were decapitated, hippocampi were excised, and the left and right hippocampus were stored separately. Sources for reagents, antibodies and supplies for Western Blot analyses are available in the Supplemental Table 1. The right hippocampus was processed for protein analysis by placing the tissue in cold (4°C) Syn-Per reagent, homogenized on ice with slow rotations of the pestle for at least 2 minutes, centrifuged for 1,200g for 10 min at 4° C, followed by transfer of the supernatant to a 1.5mL micro-centrifuge tube. Following re-centrifugation of the supernatant at 13,000 g for 20 min at 4° C, aspiration of the remaining supernatant, addition of 50 μl of N-Per reagent with 1x protease and 1x phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and short burst sonication. The protein concentration of the resultant solution was estimated using the bicinchoninic protein assay, normalized to 3 mg/mL, denatured with 2x Laemmli buffer, DL-Dithiothreitol by heating at 115⁰ C for 5 min and immediately cooling on ice upon removal from the heating block.

For western blot assays, 22.5μg protein was loaded in each well on a 10% freshly prepared gel and proteins were separated using step-wise increased electrophoreses with a running buffer for 1 hour at 90V. The 15 well gel plates were loaded as follows: first lane was used for the molecular weight ladder, 7 lanes for (2R,6R)-HNK and 7 lanes for saline treatment. Multiple gels were run for each model, with each lane a sample from a unique mouse. Hippocampal samples were selected randomly from male and female mice. The protein was transferred from gel to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using a wet transfer method and the ratios of glutamate receptor 1 (GluA1), glutamate receptor 2 (GluA2), phosphorylated voltage gated potassium channel 2.1 (p-Kv2.1), phosphorylated calcium calmodulin dependent protein kinase II (p-CaMKII), and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were determined using a Bio-Rad Gel Doc system (ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System). Additional proteins assessed using the same method included: phosphorylated protein kinase B (p-AKT), phosphorylated extracellular signal regulated kinase 1 and 2 (p-ERK(1/2)), CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CRCX4), phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 (p-EIF2SI), and phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4e (p-EIF4E). The primary outcome of the protein modulation studies was the ratio of the target to housekeeping protein (GAPDH). Image analysis performed using the ImageJ software (Version 1.53, available at github.com/ImageJ).

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of the study was the AUC0–3d of the von Frey force PWT over time (g*d) following the 3 daily injections of saline followed by (2R,6R)-HNK, naloxone followed by (2R,6R)-HNK, or NBQX followed by (2R,6R)-HNK in each of the murine models. Unadjusted AUC0–3d values were compared among groups using the Kruskal-Wallis H-test. Post hoc comparisons were made using Dunn’s test. AUC0–3d adjusted values were compared using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with mouse ID as a subject variable, group and sex as fixed variables and weight as a covariate using an exchangeable working correlation matrix structure. Unadjusted and adjusted estimated means were corrected for multiple comparisons (n=6) using the Bonferroni method.

The secondary outcome of the study was to compare the relative antiallodynic effectiveness of (2R,6R)-HNK across the murine models. The AUC0–3d values of the saline/(2R,6R)-HNK groups for each model (PI, SNI, TF) were converted to percent antiallodynic effect (PAE) by assuming that the pre-injection PWT represents a 0% antiallodynic response and the presurgical PWT represents a 100% antiallodynic response. Adjusted PAE’s were compared using a GEE as above. The differences in the estimated marginal means and Bonferroni adjusted 95% confidence intervals for 6 comparisons are reported.

The tertiary outcome was the evaluation of antiallodynic effect as well as activity, rearing and motor coordination in naïve mice given (2R,6R)-HNK 10mg/kg. PWT values were compared using a GEE with mouse ID as a subject variable and time of assessment (pre-treatment, post-treatment) as the within subject variable. Time of assessment, sex, and drug were used as factors in the model and weight as a covariate using an exchangeable working correlation matrix structure. Differences in estimated marginal means and Bonferroni adjusted 95% CI corrected for 6 comparisons are provided as measure of the effect size. Animal activity, rearing and motor coordination were compared between saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treated animals using the Mann-Whitney Test.

The immunoblot studies were exploratory. The ratio of the optical density units (ODU) of the target protein relative to housekeeping protein, GAPDH was the primary measure of interest. Differences and 95% CI of the differences in ODU protein ratios between (2R,6R)-HNK or saline treated specimens were determined using a GEE with mouse ID as a subject variable, treatment and sex as fixed factors using an exchangeable working correlation matrix structure. Post hoc comparison between sex adjusted (2R,6R)-HNK and saline estimated marginal means and 95% CI were calculated as an estimate of the effect size without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Prior to statistical analysis the distributions of the primary, secondary, tertiary and exploratory outcomes were evaluated using the one sample Kolmogorov-Smirnow test and examined graphically using q-q plots. Mouse weights were measured prior to surgery and sex differences in weights compared using an independent sample t-test. Mean difference and 95% CI of the differences were calculated using the pooled variance. Sex difference in PWT’s were compared pre surgery and prior to 1st drug treatment using the Mann-Whitney U test and median differences and 95% confidence intervals using a percentile bootstrap reported as an estimate of the effect size.

Sample size calculations

The sample size for the primary outcome in the pharmacological antagonist studies were determined to be 15 per group to achieve 80% power to detect differences among AUC’s using an F test at an alpha of 0.5 assuming an eta-squared of 0.48 which was determined from our preliminary experiments and the study of Yost et al.9 Twenty animals were included in the naïve unoperated mice study as studies of similar number of animals at a dose of (2R,6R)-HNK 10 mg/kg demonstrated an increase in glutamate concentrations in the cortical regions of the brain.5,16 The minimum number of animals for the immunoblot studies (n=14 per group) was determined to detect a difference in ratios of 0.2 with a group standard deviation of 0.175 using a two-sample t-test with a power of 80% at alpha of 0.05. Sample size analysis performed using PASS 15, release date February 10, 2020 (Power Analysis and Sample Size Software (2008). NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, ncss.com/software/pass).

A P value less that 0.05 was required to reject the null hypothesis. All statistical tests were 2-sided. Data were analyzed using RStudio version 2022.07.2 Build 576 (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA; URL: http://www.rstudio.com/) and R version 4.2.2, release date October 31, 2022 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results:

Pharmacological Antagonist Studies

Body weights and paw withdrawal thresholds of mice in the pharmacological antagonist studies are shown in Supplemental Table 2. Male mice weighed more than female mice in the SNI and TF groups prior to surgery. Prior to surgery female mice in the PI and SNI groups had reduced PWT’s compared to males; however, prior to the 1st drug treatment the combined median (1st, 3rd quartile) PWT for the PI, SNI, and TF mice were: 0.08 g (0.02, 0.25 g), 0.77 g (0.34, 0.77 g), and 0.77g (0.48, 0.77 g) and did not differ between male and female mice.

PWT’s at baseline, prior to study drug treatment and the AUC0–3d for the PI, SNI and TF inhibitor studies are shown in Figure 1. In the PI model, NBQX reduced the adjusted AUC0–3d by −3.86 g*d (95% CI −4.78 to −2.94, P<0.001) and −4.23 g*d (−5.63 to −2.84, P<0.001) compared with saline and naloxone, respectively. The adjusted AUC0–3d was reduced by −6.16 g*d (−7.10 to −5.22, P<0.001) and −5.25 g*d (−6.48 to −4.01, P<0.001) by NBQX compared to saline and naloxone in the SNI model, and by −5.15 g*d (−6.73 to −3.57, P<0.001) and −5.10 g*d (−6.64 to −3.54, P<0.001) compared to saline and naloxone in the TF model. The AUC0–3d was not different between saline and naloxone and there was no pretreatment by sex effect observed in any of the models.

Figure 1:

Box plots and dot plots with box plots of the effect of pretreatment with naloxone and NBQX on the antiallodynic efficacy of (2R,6R)-HNK in murine models of pain. The solid line is the median, the dashed line is the mean, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles, the whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circle the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Upper Panel: Plantar incision model. A: Box plot of paw withdrawal thresholds prior to surgery, prior to drug administration and 24 hours following drug administration for 3 consecutive days.

B: Dot and box plot of AUC0–3d among treatment groups. † = NBQX + (2R,6R)-HNK different from saline + (2R,6R)-HNK, difference −3.64 g*d (95% CI −5.08 to −2.21, P<0.001) and NBQX + (2R,6R)-HNK different from naloxone + (2R,6R)-HNK, difference −3.68 g*d (95% CI −6.60 to −0.72, P<0.001). Data analyzed using Dunn’s test.

Middle panel: Spared neve injury. A: Box plot of paw withdrawal thresholds prior to surgery, prior to drug administration and 24 hours following drug administration for 3 consecutive days.

A: Box plot of paw withdrawal thresholds prior to surgery, prior to drug administration and 24 hours following drug administration for 3 consecutive days.

B: Dot and box plot of AUC0–3d among treatment groups. † = NBQX + (2R,6R)-HNK different from saline + (2R,6R)-HNK, difference −6.09 g*d (95% CI −7.83 to −4.35, P<0.001) and NBQX + (2R,6R)-HNK different from naloxone + (2R,6R)-HNK, difference −5.15 g*d (95% CI −7.98 to −2.30, P<0.001). Data analyzed using Dunn’s test.

Lower Panel: Tibial fracture model. A: Box plot of paw withdrawal thresholds prior to surgery, prior to drug administration and 24 hours following drug administration for 3 consecutive days. B: Dot and box plot of AUC0–3d among treatment groups. † = NBQX + (2R,6R)-HNK different from saline + (2R,6R)-HNK, difference −5.18 g*d (95% CI −7.58 to −2.78, P<0.001) and NBQX + (2R,6R)-HNK different from naloxone + (2R,6R)-HNK, difference −4.95 g*d (95% CI −8.01 to −1.95, P<0.001). Data analyzed using Dunn’s test.

Estimation of Relative Antiallodynic Effectiveness

The unadjusted median (1st, 3rd quartile) percent antiallodynic effect of (2R,6R)-HNK 10 mg/kg in the PI, SNI and TF models following saline administration was 35.1% (29.1, 58.2%), 61.9% (39.7, 73.4%) and 65.0% (30.9, 75.2%), respectively. The adjusted mean (95% CI) antiallodynic effect of (2R,6R)-HNK in the PI, SNI and TF models was 40.7% (34.1%,47.3%), 55.1% (48.7%,61.5%) and 54.7% (46.5%,63.0%), greater in the SNI, difference 14.3% (95%CI 3.1 to 25.6%, P=0.007) and TF, difference 13.9% (95%CI 1.9% to 26.0%, P=0.019) compared to the PI model. There was no model by sex differences in the percent antiallodynic effect of (2R,6R)-HNK (P=0.58).

Effect of (2R,6R)-HNK administration in non-operated naive mice.

Male mice weighed 23.0 ± 1.1 g and female 19.8 ± 1.0 g: difference 3.2 g (95% CI, 2.2 to 4.2 g, P<0.001). Unadjusted (1st, 3rd quartile) PWT’s before (2R,6R)-HNK administration were 3.61 (1.54, 3.68) g in female and 3.68 (3.61, 3.68) g in male mice, median difference 0.07g (95% CI −0.07g to 1.89 g, P=0.72). Adjusted PWT’s were not increased following saline, mean difference −0.03 g (95% CI −0.52 to 0.44 g, P=1.00) or (2R,6R)-HNK 10 mg/kg administration, mean difference 0.22 g (95% CI −0.36 to 0.81 g, P=1.00). There was no sex by drug difference in response to (2R,6R)-HNK (P=0.36). Activity monitoring and motor strength testing demonstrated no difference in spontaneous locomotor activity or motor strength between mice treated with saline or (2R,6R)-HNK (Supplemental Figure 1).

Evaluation of Hippocampal Protein Modulation

Body weights and paw withdrawal thresholds of mice in the PI, SNI and TF Western blot study groups are shown in Supplemental Table 3. Non-operated control mice are reported above. Male mice weighed more than female mice prior to surgery in all study groups. There were no group by sex differences in the PWT’s pre-surgery or prior to the 1st drug treatment.

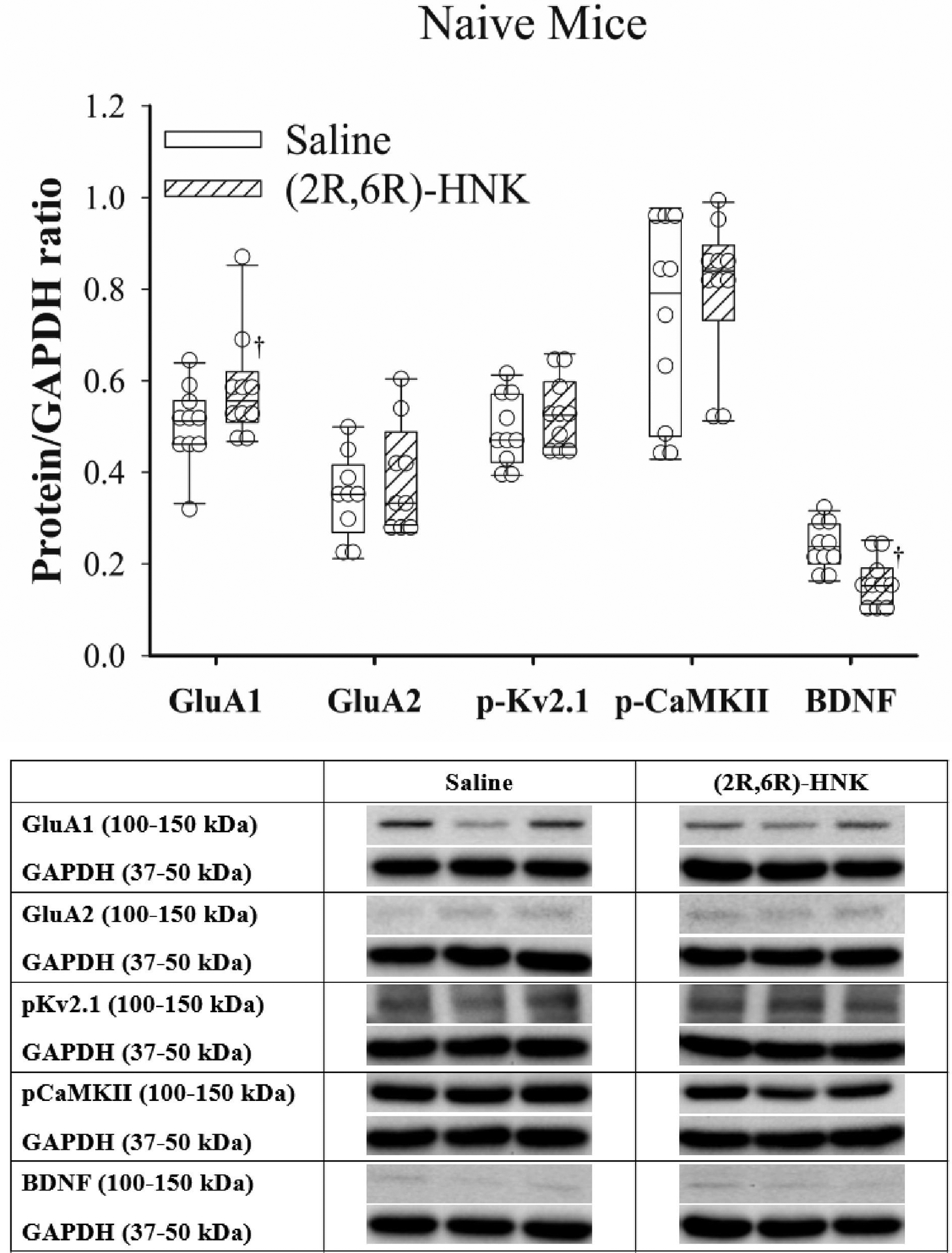

In naive animals, the adjusted hippocampal protein ratio of GluA1/GAPDH was increased and the ratio of BDNF/GAPDH was decreased in mice that received (2R,6R)-HNK compared with saline (Figure 2). The ratios of GluA2, p-CaMKII, and p-Kv2.1 were not different between saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treated mice. In PI animals, the adjusted hippocampal protein ratios of GluA1, GluA2, p-Kv2.1 and p-CaMKII to GAPDH were increased and the ratio of BDNF/GAPDH was decreased in mice that received (2R,6R)-HNK compared with saline (Figure 3). In SNI animals, the adjusted hippocampal protein ratios of GluA2, p-Kv2.1 and p-CaMKII to GAPDH were increased and the ratio of BDNF/GAPDH was decreased in mice that received (2R,6R)-HNK compared with saline (Figure 4). In TF animals, the adjusted hippocampal protein ratios of GluA1, GluA2, pKv2.1 and p-CaMKII to GAPDH were increased and the ratio of BDNF/GAPDH was decreased in mice that received (2R,6R)-HNK compared with saline (Figure 5). Means (SD) and mean differences in exploratory protein analysis are shown in Table 1. Among the exploratory proteins compared to saline treatment, (2R,6R)-HNK increased p-AKT was in the TF model, decreased p-ERK(1/2) in the naïve, PI and TF models, increased p-EIF2SI in the SNI model increased p-EIF4e following PI.

Figure 2:

Dot plots with box plots of protein/GAPDH ratios for saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treated naive mice. The solid line is the median, the dashed line is the mean, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles, the whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circle the 5th and 95th percentiles. † = (2R,6R)-HNK different from saline treated animals, P<0.05. Sex adjusted mean differences in GluA1 0.081 (95% CI 0.006 to 0.157, P=0.035), GluA2 0.046 (95% CI −0.023 to 0.11, P=0.19), pKv2.1 0.037 (95% CI −0.015 to 0.088, P=0.17), pCaMKII 0.072 (−0.031 to 0.175, P=0.17), and BDNF −0.080 (95% CI −0.111 to −0.047, P<0.001). Differences not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Representative immunoblots from the right hippocampus of 3 mice treated with saline and 3 treated with (2R,6R)-HNK. Blots of protein of interest and GAPDH (housekeeping protein) are taken from the same lane on the chromatograph.

Figure 3:

Dot plots with box plots of protein/GAPDH ratios for saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treated animals following PI surgery. The solid line is the median, the dashed line is the mean, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles, the whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circle the 5th and 95th percentiles. † = (2R,6R)-HNK different from saline vehicle animals, P<0.05. Sex adjusted mean difference in GluA1 0.187 (95% CI 0.111 to 0.263, P<0.001), GluA2 0.154 (95% CI 0.031 to 0.276, P=0.014), pKv2.1 0.196 (95% CI 0.115 to 0.276, P<0.001), pCaMKII 0.363 (95% CI 0.208 to 0.517, P<0.001), and BDNF −0.094 (95% CI −0.171 to −0.016, P<0.017). Differences not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Representative immunoblots from the right hippocampus of 3 mice treated with saline and 3 treated with (2R,6R)-HNK. Blots of protein of interest and GAPDH (housekeeping protein) are taken from the same lane on the chromatograph.

Figure 4:

Dot plots with box plots of protein/GAPDH ratios for saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treated animals following SNI surgery. The solid line is the median, the dashed line is the mean, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles, the whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circle the 5th and 95th percentiles. † = (2R,6R)-HNK different from saline vehicle animals, P<0.05. Adjusted mean difference in GluA1 0.070 (95% CI −0.055 to 0.196, P<0.393), GluA2 0.226 (95% CI 0.129 to 0.322, P<0.001), pKv2.1 0.246 (95% CI 0.155 to 0.336, P<0.001), pCaMKII 0.274 (95% CI 0.199 to 0.348, P<0.001), and BDNF −0.224 (95% CI −0.302 to −0.147, P<0.001). Differences not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Representative immunoblots from the right hippocampus of 3 mice treated with saline and 3 treated with (2R,6R)-HNK. Blots of protein of interest and GAPDH (housekeeping protein) are taken from the same lane on the chromatograph.

Figure 5:

Dot plots with box plots of protein/GAPDH ratios for saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treated animals following TF surgery. The solid line is the median, the dashed line is the mean, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles, the whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circle the 5th and 95th percentiles. † = (2R,6R)-HNK different from saline vehicle animals, P<0.05. Adjusted mean differences and 95% confidence intervals for GluA1 0.131 (95% CI 0.073 to 0.189, P<0.001), GluA2 0.203 (95% CI 0.120 to 0.285, P<0.001), pKv2.1 0.196 (95% CI 0.120 0.273, P<0.001), pCaMKII 0.180 (95% CI 0.106 to 0.253, P<0.001), and BDNF −0.208 (95% CI −0.304 to −0.113, P<0.001). Differences not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Representative immunoblots from the right hippocampus of 3 mice treated with saline and 3 treated with (2R,6R)-HNK. Blots of protein of interest and GAPDH (housekeeping protein) are taken from the same lane on the chromatograph.

Table 1:

Exploratory hippocampal protein(s) to GAPDH ratios.

| Protein | Model | N Saline/HNK | Saline | (2R,6R)-HNK 10mg/kg | Sex adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-AKT | Naive | 10/10 | 0.462 ± 0.084 | 0.453 ± 0.028 | −0.014 (−0.057 to 0.029) | 0.52 |

| PI | 14/14 | 0.656 ± 0.226 | 0.579 ± 0.268 | −0.078 (−0.253 to 0.096) | 0.38 | |

| SNI | 14/14 | 0.353 ± 0.143 | 0.339 ± 0.098 | −0.013 (−0.062 to 0.035) | 0.59 | |

| TF | 16/17 | 0.440 ± 0.228 | 0.588 ± 0.276 | 0.128 (0.069 to 0.187) | <0.001 | |

| p-ERK(1/2) | Naive | 10/10 | 0.354 ± 0.109 | 0.228 ± 0.041 | −0.118 (−0.151 to −0.085) | 0.009 |

| PI | 14/13 | 0.745 ± 0.119 | 0.638 ± 0.169 | −0.097 (−0.172 to −0.022) | 0.011 | |

| SNI | 14/14 | 0.238 ± 0.105 | 0.238 ± 0.109 | 0.000 (−0.058 to 0.058) | 0.99 | |

| TF | 16/17 | 0.779 ± 0.351 | 0.664 ± 0.307 | −0.120 (−0.218 to −0.024) | 0.015 | |

| CRCX4 | Naive | 10/10 | 0.484 ± 0.142 | 0.618 ± 0.164 | 0.134 (−0.019 to 0.287) | 0.48 |

| PI | 20/20 | 0.936 ± 0.415 | 0.802 ± 0.259 | −0.134 (−0.329 to 0.061) | 0.18 | |

| SNI | 17/17 | 1.028 ± 0507 | 0.550 ± 0.075 | −0.396 (−0.466 to −0.326) | 0.037 | |

| TF | 16/17 | 0.481 ± 0.221 | 0.432 ± 0.184 | −0.049 (−0.113 to 0.154) | 0.14 | |

| p-EIF2SI | Naive | 10/10 | 0.353 ± 0.179 | 0.408 ± 0.165 | 0.054 (−0.103 to 0.212) | 0.48 |

| PI | 14/13 | 0.421 ± 0.108 | 0.478 ± 0.195 | 0.064 (−0.037 to 0.166) | 0.21 | |

| SNI | 18/19 | 0.448 ± 0.184 | 0.684 ± 0.231 | 0.235 (0.096 to 0.374) | 0.002 | |

| TF | 14/14 | 0.354 ± 0.072 | 0.395 ± 0.188 | 0.040 (−0.013 to 0.095) | 0.14 | |

| p-EIF4E | Naive | 10/10 | 0.338 ± 0.072 | 0.327 ± 0.039 | −0.013 (−0.046 to 0.020) | 0.45 |

| PI | 14/14 | 0.353 ± 0.073 | 0.459 ± 0.087 | 0.106 (0.051 to 0.161) | 0.002 | |

| SNI | 14/14 | 0.374 ± 0.139 | 0.452 ± 0.122 | 0.078 (−0.023 to 0.180 | 0.13 | |

| TF | 16/17 | 0.338 ± 0.072 | 0.377 ± 0.078 | 0.008 (−0.041 to 0.058) | 0.73 |

Data presented as mean ± SD. Adjusted differences estimated using a generalized estimating equation with sex and group as fixed factors with an exchangeable correlation matrix structure. Differences not adjusted for multiple comparisons. N = number of lanes of Western plot data included in the analysis. Model: PI = plantar incision, SNI = spared nerve injury, TF = tibial fracture with pinning and casting.

Discussion:

The important new findings of this study include the finding that the relative antiallodynic effect of (2R,6R)-HNK is model dependent, demonstrating a greater relative effectiveness in chronic compared with acute pain models. Our findings extended those of Yost et al, demonstrating that (2R,6R)-HNK analgesic activity is blocked by pretreatment with a brain penetrating AMPA antagonist in both acute and chronic pain models. Similar to prior studies we found that (2R,6R)-HNK administration was associated with an increase in GluA1 and GluA2.5,7 Novel to this study in murine pain models, we demonstrated an increase in the activity of CaMKII a serine/threonine protein kinase that phosphorylates the GluA1 AMPA, regulating the number of AMPA receptors together with their conductance in the post synaptic density.17 In addition, we observed an increase in the phosphorylated ion channels Kv2.1, a voltage gated potassium channel that is critical to the control of neuronal excitability.18

Prior studies in murine models of depression have demonstrate that (2R,6R)-HNK enhanced GluA1, GluA2 activity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus and increased BDNF protein concentrations which was abolished by pretreatment with NBQX.5,16,19 Contrary to the studies in murine models of depression we observed an decrease in hippocampal BDNF following (2R,6R)-HNK administration in murine models of pain. Our findings concur with those of Jin et al who demonstrated using transcriptomic analysis of the prelimbic cortex that SNI pain was associated with increased BDNF signaling, abnormal dendritic spine organization, and reduced AMPAR activity and that (2R,6R)-HNK administration decreased BDNF in the prelimbic cortex with compared to saline.10 The authors suggested that the analgesic activity of (2R,6R)-HNK depends on modulation of the BDNF/ARC/AMPA axis possibly through reduction in BDNF(TrkB) pathway activity.10 Our finding of a decrease ratio of BDNF in the hippocampus supports the aforementioned hypothesis.

Our exploratory analysis revealed increased phosphorylation in AKT and decreased ERK phosphorylation in mice that received (2R,6R)-HNK following a tibial fracture. BDNF has been demonstrated to be involved in fracture healing via both the AKT and ERK1/2 pathways.20 We also observed small differences between saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treatment on hippocampal EIF2S1 and EIF4E proteins. These are members of the scaffolding proteins and the antidepressant effects of (2R,6R)-HNK depend on the 4E binding proteins through the activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 4E-BP signaling pathway.21 Zanos et al. found negligible differences at 24 hours in EIF2S1 between saline and (2R,6R)-HNK treatments.5

Similar to our findings, Yost et al, demonstrated that (2R,6R)-HNK produces antinociception lasting more than 24 h in a murine peripheral nerve injury model.9 These authors concluded that the effects of (2R,6R)-HNK differed in time course and mechanism and had a better safety profile than ketamine, and that (2R,6R)-HNK had a longer analgesic effect than gabapentin in neuropathic mice.9 Unlike ketamine, (2R,6R)-HNK possesses no quantifiable binding to the ketamine/MK801 site of the NMDA receptors at concentration up to 100 mM, and only modest functional inhibition at higher concentrations.22 Treatment with (2R,6R)-HNK did not produce behavioral effects, toxicity or any evidence of Olney’s lesion formation in rats suggesting no NMDAR-antagonist neurotoxicity of (2R,6R)-HNK.23 In addition, in the current study and that of Yost et al. analgesia was not affected by pretreatment with naloxone or naltrexone, suggesting that opioid receptors do not modulate (2R,6R)-HNK analgesia.9

Unlike our finding, prior studies suggest that (2R,6R)-HNK increased BDNF levels in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray producing an antidepressant-like effect with increasing aggression in mice.19,24 The increased aggression was blocked by an AMPA receptor antagonist and the authors cautioned that increased aggression could be a cautionary concern for future drug development of (2R,6R)-HNK.19 Similar to the findings of Goswami et al of no (2R,6R)-HNK impairment of locomotor activity in the open field test,25 we did not observe any effects on ambulation or rearing at 30 minutes following (2R,6R)-HNK. We also did not observe an effect on motor strength in naive mice and have not observed aggressive behavior in mice administered doses up to 30 mg/kg. Highland et al. in a review of preclinical studies with hydroxynorketamines found that (2R,6R)-HNK lacks overt adverse effects, including the NMDAR inhibition–mediated anesthetic actions, dissociative properties, or abuse liability.26

A strength of our study is that the use of the outbred (CA1) strain adds generalizability of our findings as prior studies with (2R,6R)-HNK have exclusively used inbred C57BL/6 mice and the gender effect seen in many murine pain models is strain dependent.27 Nevertheless the results of our study should only be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Preclinical pain models in mice may not accurately represent pain in humans and effective treatments in mice may not translate to humans. Our protein analysis was exploratory, and we chose to evaluate a large number of proteins; therefore, some of our finding may be by chance as we did not control the family wide error rate for these analyses. We tested (2R,6R)-HNK at a single dose, 10 mg/kg and although this dose is allometrically like doses of ketamine that have been clinically, we do not know if similar doses will provide analgesia in humans. Difference in mouse weight between sex at similar age of acquisition may have been increased because of coronavirus disease related restrictions in vivarium usage during the study period. We administered (2R,6R)-HNK via an intraperitoneal route, so brain area specific effects of the protein changes cannot conclusively suggest that the hippocampus is the specific site of the analgesic effects observed. However, we selected to evaluate protein changes in the hippocampus as the hippocampus is an integral part of the limbic system and is long recognized as playing an essential role in learning and memory. The hippocampus has distinct functional regions along its longitudinal axis; the dorsal hippocampus underlies primarily memory and cognitive functions while the ventral hippocampus prominently relates to emotion, stress, and anxiety. Of these two structures, several studies have shown that the ventral hippocampus has a potential role in modulating the development of chronic pain,28 and that increased excitability in hippocampal CA3 areas has been shown to depend on BDNF/TrkB activation.29 Pain especially persistent or chronic are known to produce profound effects on hippocampal anatomy, metabolism, morphology, and function.

Conclusions

Our findings suggests that the analgesic benefit of (2R,6R)-HNK is AMPA dependent and that (2R,6R)-HNK was associated with increased GluA1, GluA2, p-Kv2.1, p-CaMKII and decreased BDNF in the hippocampus of mice with acute and chronic pain. Potential clinical development of (2R,6R)-HNK is currently underway. The FDA has confirmed the classification of (2R,6R)-HNK as a drug and has issued an IND/EudraCT number: 143526. A Phase I evaluation of (2R,6R)-HNK is currently underway (NCT04711005).

Supplementary Material

KeyPoints:

Question:

Does the ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine ((2R,6R)-HNK) reduce mechanical allodynia in acute and chronic murine pain models via an α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate (AMPA) mediated pathway and what protein changes are observed in the hippocampus of mice treated with (2R,6R)-HNK compared with mice that receive saline?

Findings:

(2R,6R)-HNK 10mg/kg demonstrated AMPA receptor dependent analgesia with an antiallodynic potency greater in chronic compared to acute models of pain and increased GluA1 and GluA2 unit proteins of the AMPA receptor, reduced BDNF and increased p-Kv2.1 proteins in the mouse hippocampus.

Meaning:

This study demonstrated (2R,6R)-HNK AMPA dependent analgesia that likely involve the BDNF(TrkB) and Kv2.1 pathways and may represent a novel analgesic agent for clinical use for multiple pain conditions.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Craig J. Thomas, Ph.D. Leader, Division of Preclinical Innovation, Chemistry Technologies, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health for supplying the (2R,6R)-HNK used in the study and the Department of Anesthesiology, Rush University for funding the laboratory facilities to support our work.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institute of Health under award number RO1AT009680-02S1. The drug used in this study, (2R,6R)-HNK was provided as a gift in kind by Craig J. Thomas, Ph.D. Leader, Division of Preclinical Innovation, Chemistry Technologies, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Glossary of terms:

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate

- AMPAR

α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate receptor

- ARRIVE

Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments

- ARC

Activity Regulated Cytoskeleton-protein

- AUC

Area Under Curve

- BDNF

Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor

- C

Celsius

- CA3

Cornu Ammonis subfield 3

- Ca2+

Calcium

- CAMK2

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CXCR4

CXC Chemokine Receptor 4

- DPBS

Dulbecco Phosphate Buffered Saline

- ERK

Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GEE

Generalized estimating equations

- GluA1

Glutamate Ionotropic Receptor (AMPA) type subunit 1

- GluA2

Glutamate Ionotropic Receptor (AMPA) type subunit 2

- HBSS

Hanks Balanced Sodium Salt

- HNK

Hydroxynorketamine

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- IP

Intraperitoneal

- JNK

C-Jun N-terminal Kinase

- Kv2.1

Voltage-gated Potassium Channel 2.1

- mGlu2

Metabotropic glutamate 2 receptors

- NBQX

1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxobenzo [f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PBS

Phosphate Buffered Saline

- PI

Plantar Incision

- p-AKT

Phosphorylated Protein Kinase B

- p-CAMK2

Phosphorylated-Calcium/Calmodulin Dependent Protein Kinase 2

- p-EIF2S1

Phosphorylated Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2 Subunit 1

- p-EIF4E

Phosphorylated Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4e

- p-ERK(1/2)

Phosphorylated Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinases 1 and 2

- p-Kv2.1

Phosphorylated Voltage Gated Potassium Channel 2.1

- PWT

Paw Withdrawal Threshold

- SNI

Spare Nerve Injury

- TF

Tibial Fracture with Casting

- TrkB

Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase B

- WB

Western Blot

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: C.J.T., is listed as a coauthor in a patent application related to the pharmacology and use of (2R,6R)-HNK in the treatment of depression, anxiety, anhedonia, suicidal ideation, and posttraumatic stress disorders. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclosures: Part of the work in this article have been presented at the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) annual meetings, San Francisco CA, October 13th, 2018; Orlando FL, October 20th and 22nd, 2019; Virtual meeting, October 5th, 2020; San Diego CA October 9th and 10th, 2021; and New Orleans LA, October 22nd and 23rd, 2022.

References:

- 1.Cohen SP Bhatia A Buvanendran A et al. Consensus Guidelines on the Use of Intravenous Ketamine Infusions for Chronic Pain From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018; 43:521–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwenk ES, Viscusi ER, Buvanendran A, et al. Consensus Guidelines on the Use of Intravenous Ketamine Infusions for Acute Pain Management from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humo M, Ayazgök B, Becker LJ Waltisperger E Rantamäki T Yalcin I: Ketamine induces rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects in chronic pain induced depression: Role of MAPK signaling pathway. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2020;100:109898. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Highland JN, Zanos P, Riggs LM, et al. Hydroxynorketamines: Pharmacology and Potential Therapeutic Applications. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73:763–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016; 533:481–6. doi: 10.1038/nature17998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanos P, Highland JN, Stewart BW, et al. (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine exerts mGlu2 receptor-dependent antidepressant actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:6441–6450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ju L, Yang J, Zhu T, Liu P, Yang J. BDNF-TrkB signaling-mediated upregulation of Narp is involved in the antidepressant-like effects of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine in a chronic restraint stress mouse model. BMC Psychiatry. 2022. Mar 15;22(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03838-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroin JS Das V Moric M Buvanendran A: Efficacy of the ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine in mice models of pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2019;44:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yost JG, Wulf HA, Browne CA, Lucki I. Antinociceptive and Analgesic Effects of (2R,6R)-Hydroxynorketamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2022;382:256–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin T, Ng HLL, Jiang Y, Ho I, et al. (2R,6R)-Hydroxynorketamine restores postsynaptic localization of AMPAR in the prelimbic cortex to provide sustained pain relief, 17 November 2022, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square [ 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2261014/v1] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. BMJ Open Science 2020; 4:e100115. doi: 10.1136/bmjos-2020-100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th edition. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54050 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacquez B, Choi H, Bird CW, Linsenbardt DN, Valenzuela CF. Characterization of motor function in mice developmentally exposed to ethanol using the Catwalk system: Comparison with the triple horizontal bar and rotarod tests. Behav Brain Res. 2021; 396:112885. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deacon RMJ. Measuring motor coordination in mice. J Vis Exp. 2013; 75:e2609. doi: 10.3791/2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou D, Peng HY, Lin TB, et al. (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine rescues chronic stress-induced depression-like behavior through its actions in the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Neuropharmacology. 2018; 139:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zalcman G, Federman N, Romano A. CaMKII Isoforms in Learning and Memory: Localization and Function. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:445. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misonou H, Mohapatra DP, Trimmer JS. Kv2.1: a voltage-gated k+ channel critical to dynamic control of neuronal excitability. Neurotoxicology. 2005; 26:743–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou D. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray contributes to (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine-mediated actions. Neuropharmacology. 2020; 170:108068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z, Hu P, Wang Z, Qui X, Chen Y. BDNF promoted osteoblast migration and fracture healing by up-regulating integrin β1 via TrkB-mediated ERK1/2 and AKT signaling. J Cell Mol Med 2020; 24:10792–10802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguilar-Valles A, De Gregorio D, Matta-Camacho E, et al. Antidepressant actions of ketamine engage cell-specific translation via eIF4E. Nature. 2021;590(7845):315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumsden EW Troppoli TA Myers SJ et al. Antidepressant-relevant concentrations of the ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine do not block NMDA receptor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:5160–5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris PJ Burke RD Sharma AK et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and NMDAR antagonism-associated neurotoxicity of ketamine, (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine and MK-801. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2021;87:106993. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2021.106993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye L, Ko CY, Huang Y, Zheng C, Zheng Y, Chou D. Ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine enhances aggression via periaqueductal gray glutamatergic transmission. Neuropharmacology 2019; 157:107667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goswami N, Aleem M, Manda K. Intranasal (2R, 6R)-hydroxynorketamine for acute pain: Behavioural and neurophysiological safety analysis in mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2023; 50:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Highland JN, Morris PJ, Konrath KM, et al. Hydroxynorketamine Pharmacokinetics and Antidepressant Behavioral Effects of (2,6)- and (5R)-Methyl-(2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamines. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2022; 13:510–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith JC. A review of strain and sex differences in response to pain and analgesia in mice. Comparative Medicine 2019; 69:490–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao S, Zheng Y, Fu Z, et al. Ventral hippocampal CA1 modulates pain behaviors in mice with peripheral inflammation. Cell Rep. 2023; 42:112017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aungst S, England PM, Thompson SM. Critical role of trkB receptors in reactive axonal sprouting and hyperexcitability after axonal injury. J Neurophysiol. 2013. Feb;109(3):813–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.