Abstract

By using random mutagenesis and enrichment by chemostat culturing, we have developed mutants of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum that were unable to grow under hydrogen-deprived conditions. Physiological characterization showed that these mutants had poorer growth rates and growth yields than the wild-type strain. The mRNA levels of several key enzymes were lower than those in the wild-type strain. A fed-batch study showed that the expression levels were related to the hydrogen supply. In one mutant strain, expression of both methyl coenzyme M reductase isoenzyme I and coenzyme F420-dependent 5,10-methylenetetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase was impaired. The strain was also unable to form factor F390, lending support to the hypothesis that the factor functions in regulation of methanogenesis in response to changes in the availability of hydrogen.

Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum grows on molecular hydrogen and CO2 as its sole energy and carbon source. For several key reactions involved in the reduction of CO2 to methane, M. thermoautotrophicum contains two or more isoenzymes or functionally equivalent enzymes.

The final, methane-forming step in methanogenesis is catalyzed by methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR). Of this enzyme, two differentially expressed isoenzymes (MCR I and MCR II) have been found (1, 7, 8, 10, 13). Expression of MCR II is favored by conditions characterized by excess substrate or energy supply (high gassing rates, extensive stirring), low temperature (55°C), and alkaline pH (pH 7.5) and predominates during the exponential growth phase in a fed-batch culture. MCR I, on the other hand, is preferentially expressed under the opposite conditions (i.e., low gassing and fermentor impeller speeds, high temperature [70°C], acidic pH [pH 6.5]) and predominates in the later stages of growth (1). Differential expression of these isoenzymes is regulated at the transcriptional level (7, 8). Similar expression patterns have been found for the two enzymes that are involved in the reduction of N5,N10-methylenetetrahydromethanopterin to N5,N10-methylenetetrahydromethanopterin. One of these enzymes, F420-dependent methylenetetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase (F420-MDH), behaves similarly to MCR I. Expression of its counterpart, hydrogen-using MDH (H2-MDH), proceeds analogously to that of MCR II (7, 8). The different forms of each enzyme appear to be genetically distinctly regulated (1, 7, 8, 10, 13, 20).

The metabolic regulation of the enzymes involved in the methanogenic pathway has been the subject of extensive research, but these studies have focused mainly on the connection between enzyme expression and environmental factors such as hydrogen availability. Regulation in response to variations in the hydrogen supply presumes the presence of suitable (hydrogen-)sensing and signal transduction systems whose nature is essentially unclear to us. The obvious strategy for unraveling such systems is the isolation and characterization of mutants that are defective in such regulation. M. thermoautotrophicum is well characterized at the DNA level. However, the direct approach in mutant preparation by using site-directed mutagenesis of putative regulatory elements is hampered by the fact that transformation systems for the organism have not been established. In addition, the more classical approach for making mutants that are defective in hydrogen regulation by random mutagenesis has also not been described. In the present study, we developed the latter method by using chemostat culturing under excess-hydrogen conditions and selection and testing of suitable clones. The results are described herein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Coenzyme F420-2 and 8-OH adenylated F420 (factor F390) were prepared as described previously (19). Synthetic oligonucleotide primers were from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium), Hybond-N+ membranes were from Amersham (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), and other molecular biological reagents were from either Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany) or Eurogentec. Gelrite was purchased from Kelco (San Diego, Calif.). Hydrogen and carbon dioxide gases were supplied by Hoek-Loos (Schiedam, The Netherlands) and freed from traces of oxygen by passage over a BASF RO-20 catalyst at room temperature. The catalyst was a gift from BASF. All other chemicals used were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) or Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) and were of the highest grade available.

Media composition.

All media employed contained the following constituents: KH2PO4, 6.8 g/liter; Na2CO3, 3.3 g/liter; NH4Cl, 2.1 g/liter; cysteine · HCl · H2O, 0.6 g/liter; a 0.1% (vol/vol) concentration of a trace element stock solution (14); and resazurin (1 μg/liter) as a redox indicator. In addition to this, standard (N) medium contained 0.6 g of Na2S · 2H2O per liter and had a pH of 7.0; MI medium contained 0.5 g of Na2S2O3 per liter and had a pH of 6.5; and MII medium contained 6.0 g of Tris and 0.6 g of Na2S · 2H2O, each per liter, and had a pH of 8.0. The pH values given are those prevailing under culturing conditions. In the case of MI medium, the pH was adjusted with HCl before gassing was done; no adjustment of pH was necessary for N and MII media. To test for conditional auxotrophy, MI medium was supplemented with 2.5% (vol/vol) sterilized cell extract prepared from wild-type M. thermoautotrophicum. Chemostat medium was essentially the same as MII medium but with fivefold less NH4Cl. Fed-batch medium was the same as MII medium but contained 0.5 g of Na2S2O3 per liter and lacked the resazurin and Na2S · 2H2O. Solid media also contained 0.75 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O and 8 g of Gelrite, each per liter (6). Growth was carried out under an H2-CO2 (80%–20% [vol/vol]) atmosphere.

Mutant isolation.

M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH (DSM 1053) was grown on chemostat medium in a 0.5-liter chemostat at 55°C with a culture volume of 300 ml, a gassing rate of 12 liters/h, and magnetic stirring at 400 rpm. The dilution rate was gradually increased from 0.067 to 0.15 h−1. Three twice-monthly additions of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine were made to a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml.

At regular times, samples were aseptically and anoxically withdrawn and inoculated into 100-ml serum flasks containing 20 ml of either MI or MII medium. Cultures were incubated at 68°C without further agitation (MI medium) or in a rotary incubator (150 rpm) at 55°C (MII medium). Growth was monitored by measuring methane production. Chemostat culturing was continued until the samples did not show any detectable growth on MI medium. Serial dilutions of the culture obtained were plated on solid MII medium and subsequently incubated at 55°C in an anaerobic jar pressurized at 0.5 bar (1 bar = 105 Pa). Individual colonies appeared within a week and were picked and tested for growth on plates with MII (55°C) and MI (68°C) media. Some of the clones that grew only on solid MII medium were selected for further study. Preliminary experiments with the wild type indicated a plating efficiency of nearly 100% on both MI and MII media.

Physiological characterization.

Cells were grown in 100-ml serum flasks containing 20 ml of MI, N, or MII medium, pressurized at 1.2 bars with 80% H2–20% CO2. Flasks were incubated under stationary conditions at 68 or 55°C or in a rotary incubator (150 rpm) at 55°C. Growth rates were determined by measuring the methane production at regular intervals. This was done by analyzing 0.5-ml amounts of the headspace on a Pye Unicam GCD chromograph equipped with a Porapack Q 100/200 mesh column. Ethane was used as an internal standard. After cessation of growth, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was determined for dry weight calculation, at which an OD600 of 1 corresponded to 325 mg (dry weight) liter−1. All experiments were done at least in duplicate.

Molecular characterization.

Cells of the various strains were grown in 100-ml serum flasks on MII medium (at 55°C with agitation). After the cells were harvested, RNA was isolated and used for Northern and dot blot analyses essentially as described previously (9). Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled oligonucleotide probes against F420-MDH, H2-MDH, MCR I, and MCR II were made by PCR amplification of M. thermoautotrophicum DNA by using the Boehringer PCR DIG labeling mix and oligonucleotide primers described previously (9). For Northern blot analyses, RNA preparations and DIG-labeled DNA molecular weight marker III (Boehringer) were subjected to glyoxal-dimethyl sulfoxide denaturation and separated on a 1% agarose gel. After electrophoresis, the nucleic acids were vacuum blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane. For dot blot analyses, serial dilutions of formaldehyde-denatured RNA samples were spotted on the membrane. Membrane-bound RNA was hybridized with DIG-labeled oligonucleotide probes. After autoradiography, relative amounts of the various types of mRNA were compared, using the data obtained with the wild-type strain as a reference. The hybridization signal obtained with the 16S rRNA probe was routinely used to check if sample preparation and analyses had taken place properly.

Batch culture experiments.

Strain JB2 was cultured in a 12-liter fed-batch fermentor on 10 liters of fed-batch medium at 55°C with gassing at 2 liters min−1 with H2-CO2 (80%–20% [vol/vol]). Growth was monitored by measuring the OD600. The stirring rate was modified during growth. Samples were taken regularly from the culture; this was followed by RNA extraction and further molecular analyses as described above. The F420-MDH hybridization signal obtained for the first sample was used as a reference.

Factor F390 analyses.

Serum bottle cultures were exposed to 5% O2 for 16 h to allow factor F390 synthesis to proceed (5), after which 1 volume of acetone was added. These mixtures were shaken for 2 h at room temperature and centrifuged at 20,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant, containing coenzymes, was concentrated by rotary evaporation to a volume of 5 ml. The pH of the samples was adjusted to 5 with 2 M acetic acid. After a brief spin to remove the precipitate formed, the samples were desalted on a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters Associates, Milford, Mass.), freeze-dried, and redissolved in 1 ml of demineralized water. Reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a LiChrospher 100 RP-18 column (Merck). Forty millimolar formic acid (pH 3.0, solvent A) and 80% methanol (solvent B) were used as solvent systems. Subsequent to injection of the sample, the column was eluted for 2 min with 5% solvent B, followed by a 15-min linear gradient of 5 to 60% solvent B, a 5-min wash with 60% solvent B, and a 5-min linear gradient back to 5% solvent B. After a 5-min equilibration with 5% solvent B, the system was prepared for a further analysis. Eluted compounds were detected with a fluorescence detector set at an excitation wavelength of 390 nm and an emission wavelength of 444 nm. Retention times and UV-visible light spectra of relevant peaks were compared to those of the coenzyme F420-2 and factor F390 standards.

RESULTS

Preparation of mutants.

For preparation of mutants of M. thermoautotrophicum that required a high level of hydrogen, we employed the strategy of using random mutagenesis and enrichment by chemostat culturing. The use of a chemostat allows for cultivation and therefore selection for prolonged periods of time without much additional work. Also, exposures to a mutagenic compound can be easily done; after this, the compound concentration will gradually decrease since it will wash out of the culture. The chemostat medium had a fivefold-reduced concentration of NH4Cl to create a situation in which hydrogen was nonlimiting for growth (9, 20). This, as well as the other conditions (high H2-CO2 gassing rate of 12 liters/h, temperature of 55°C, pH of 8.0, sodium sulfide as the medium reductant, high dilution rate of 0.15 h−1), was used to induce selective pressure for the type of mutants desired. To check whether we had successfully enriched for the mutants unable to grow under hydrogen-deprived conditions, samples were collected weekly and incubated in two different ways. The first incubation was performed on MII medium (pH 8.0, sulfide as the reductant), at 55°C, in a rotary incubator to ensure high hydrogen mass transfer. This incubation corresponds to conditions for preferential expression of MCR II and H2-MDH (1, 7, 8, 9, 20). The other incubation took place at 68°C on MI medium (pH 6.5, thiosulfate) with no agitation, conditions which correspond to a low supply of hydrogen and preferential expression of MCR I and F420-MDH (1, 7, 9, 20).

Within 2 months after the first addition of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine, the chemostat sample showed growth on MII medium only. This enrichment culture was plated, and 20 of 74 colonies that were screened showed growth on solid MII and not on solid MI medium. These 20 clones were tested for reversion by repeated plating on MI plates by using a total of 106 to 108 cells for each clone. We found that six clones proved to be stable (i.e., did not produce any colonies on MI medium under repeated plating experiments). These were chosen for further study.

Physiological characterization.

The various mutant strains showed a clear difference from the wild-type strain based on physiological characterization (Table 1). In general, all of the mutants grew only when incubated at 55°C in a rotary incubator, whereas the wild-type strain showed exponential growth under all conditions tested. This indicates that the presence of agitation, and therefore of gas diffusion, determined whether proper growth took place. Table 1 also shows that exponential growth took place in strains on all three culture media when incubated at 55°C with agitation, whereas only poor growth, if any, was demonstrated by the mutant strains grown under stationary conditions irrespective of the culture medium used. The growth rates of the mutant strains do not, therefore, depend on the medium pH. Nor do they depend on the temperature, since, of the cultures incubated at 55°C, only those incubated in a rotary incubator showed exponential growth. Addition of 2.5% (vol/vol) sterilized cell extract to MI medium incubated under stationary conditions at 68°C did not affect growth of the mutants, ruling out the possibility of conditional auxotrophy. Thus, the mutant strains were mutated in such a way that they were, as intended, strongly dependent on a high supply of hydrogen.

TABLE 1.

Generation times and growth yields of the various strains cultured in serum bottles

| Strain or culture | Results under growth conditionsa of:

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68°C, stationary

|

55°C, stationary

|

55°C, with agitation

|

||||||||||||||

| MI

|

N

|

MII

|

N

|

MII

|

MI

|

N

|

MII

|

|||||||||

| Td | Y | Td | Y | Td | Y | Td | Y | Td | Y | Td | Y | Td | Y | Td | Y | |

| Wild type | 5.8 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 7.6 | 1.1 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 1.0 |

| Enrichment culture | ± | 0.6 | ± | 0.4 | ± | 0.7 | ± | 1.1 | ± | 0.9 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 6.2 | 0.8 | 5.9 | 0.6 |

| JB1 | ± | 0.8 | 6.1 | 0.9 | ± | 1.0 | ± | 1.2 | ± | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| JB2 | ± | 0.8 | − | − | ± | 1.1 | ± | 1.2 | ± | 1.1 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 1.1 |

| JB3 | ± | 0.5 | − | − | ± | 0.7 | ± | 1.2 | ± | 0.9 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| JB4 | ± | 0.4 | − | − | ± | 0.7 | ± | 1.0 | ± | 1.0 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 4.5 | 0.8 |

| JB5 | ± | 0.4 | ± | 1.0 | ± | 0.8 | ± | 1.1 | ± | 1.0 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 0.9 |

| JA1 | ± | 0.7 | ± | 1.0 | ± | 1.0 | ± | 1.2 | ± | 1.0 | 4.8 | 1.1 | 7.9 | 0.9 | 7.1 | 0.9 |

Media (20 ml) were composed as described in Materials and Methods with the following modifications: standard (N) medium contained 0.6 g of Na2S · 2H2O per liter and had a pH of 7.0; MI medium contained 0.5 g of Na2S2O3 per liter and had a pH of 6.5; MII medium contained 6.0 g of Tris and 0.6 g of Na2S · 2H2O, each per liter, and had a pH of 8.0. Td, doubling time (hour−1) of methane formed; Y, growth yield (grams [dry weight] per mole of methane); ±; poor, linear growth rather than exponential growth, −; no detectable growth.

Whenever exponential growth took place, the mutant strains grew at rates that were generally lower than those of the wild type under corresponding conditions. A comparison of the growth yields of the wild-type strain grown at 55°C with agitation in the three different media showed an increase, from MII medium to N medium to MI medium. This increase was not observed for strains JB3, JB4, and JB5. Especially for strains JB3 and JB4, the growth yields of the cultures incubated on MI medium at 55°C with agitation were considerably lower than that of the wild type.

Of all the mutant strains, strain JA1 gave the lowest growth rates. In addition, its growth yields were also considerably lower than those of the wild-type strain.

Molecular characterization.

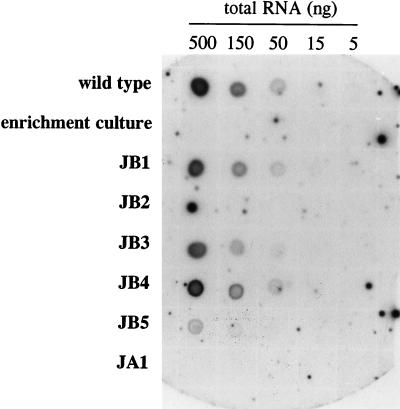

RNA isolated from the various strains grown on MII medium (at 55°C with agitation) was analyzed to determine expression levels of the MCR and MDH isoenzymes. Since Northern blots yielded a specific band of the desired size (9), quantification was done routinely by using dot blots (Fig. 1; Table 2). The wild-type strain was found to express all four of the enzymes examined, with levels of MCR II and H2-MDH mRNA transcripts being twofold higher than those of their counterparts. The mRNA levels of the enzymes mentioned were usually lower in the mutant strains than in the wild type. Also, the ratios between both forms of MDH and MCR in the mutants were different from those found in the wild-type strain under corresponding conditions. Surprisingly, although the enrichment conditions used favor expression of MCR II and H2-MDH (1, 7), some strains had higher expression levels of MCR I or F420-MDH mRNA than did their corresponding counterparts. No MCR I mRNA could be detected in strain JB2 in the serum bottle cultures, nor in the chemostat enrichment culture. Strain JA1 lacked both MCR I and F420-MDH mRNAs. This was substantiated by mass-culturing JA1 in a fed-batch fermentor. Both mRNA analyses and enzyme analyses, performed as described by Vermeij et al. (20), showed MCR I and F420-MDH to be completely absent in strain JA1, whereas MCR II and H2-MDH were present in high levels (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Dot blot analysis of MCR I mRNA levels in wild-type M. thermoautotrophicum, the chemostat enrichment culture, and mutant strains. Organisms were grown in 100-ml serum bottles under MII medium conditions. The analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 2.

Expression levels of isoenzymes in the various strainsa

| Strain or culture | mRNA expression levels

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F420-MDH | H2-MDH | Ratio | MCR I | MCR II | Ratio | |

| Wild type | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.5 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.5 |

| Enrichment culture | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.9 | NDb | 0.1 | |

| JB1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 |

| JB2 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.5 | ND | 0.15 | |

| JB3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.5 |

| JB4 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 |

| JB5 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| JA1 | 0 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0 |

The amounts of mRNA were estimated by dot blot analyses, with that of the wild-type strain taken as 1. Culturing and other methods were performed as described in the text. Values in parentheses refer to the ratio between wild-type mRNA levels of both forms of MDH and MCR, respectively.

ND, not detectable.

Batch culture experiments.

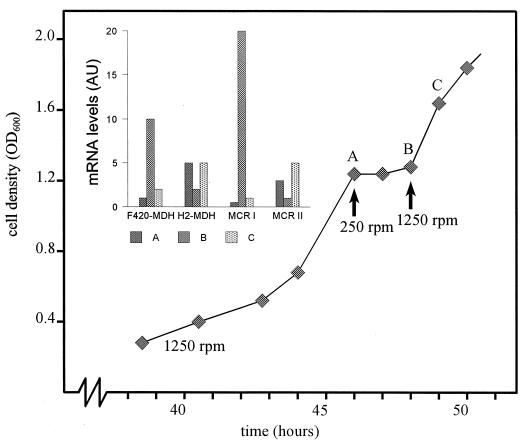

mRNA levels were much lower in the mutant strains isolated than in the wild type (Table 2). This could be due to a global impairment in RNA synthesis or to an increase in RNase activity. To exclude the possibility of a general malfunctioning in the RNA housekeeping, strain JB2 was cultured in a fed-batch fermentor. We varied the hydrogen supply to the cells by changing the impeller speeds (Fig. 2). Under conditions of extensive gassing and rapid stirring (1,250 rpm) strain JB2 grew exponentially with a doubling time (Td) of 3.5 h. mRNA levels of H2-MDH and MCR II were now fully comparable to those of the wild type (Td = 3 h) grown under the same conditions. During the exponential growth phase, the mRNA level of H2-MDH clearly predominated over that of F420-MDH. Now, MCR I mRNA transcripts could be detected, albeit only at very low levels. A change in the stirring rate from 1,250 to 250 rpm, which causes a sudden decrease in hydrogen availability (7), was accompanied by a sharp drop in the growth rate. Simultaneously, F420-MDH and MCR I mRNA levels were increased at least 20- and 40-fold, respectively, whereas H2-MDH and MCR II mRNA levels were decreased. When the original impeller rate (1,250 rpm) was subsequently restored, growth resumed and the mRNAs returned to approximately their original levels. The experiment demonstrates that the low levels of mRNA found in the serum flask incubations (Table 2) were most likely the result of a limitation in hydrogen mass transfer.

FIG. 2.

Fed-batch culture of strain JB2. The cell density is plotted against time. Changes in impeller speed are indicated by arrows. The inset shows mRNA levels (arbitrary units) at the different time points (A, B, and C) estimated by dot blot analyses; 1 AU is defined as the amount of F420-MDH RNA at time point A.

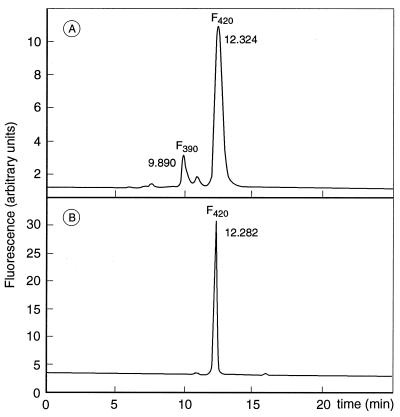

Factor F390 analyses.

Previous research has led to the hypothesis that factor F390 might function as a signal molecule of the reduction-oxidation state of the cell and as an effector in regulation of expression (19–21). To examine whether the mutant strains were affected in their factor F390 synthesis, the various strains were subject to analyses of factor F390 levels formed upon oxygen exposure. HPLC analyses (Fig. 3) revealed that most of the strains obtained were capable of forming factor F390. No significant variation in factor F390 levels was found among most of the strains, with the exception of strain JA1. In this strain, factor F390 remained absent. In agreement herewith, no factor F390 synthetase activity could be detected in cell extract from strain JA1 mass cultured in a fed-batch fermentor.

FIG. 3.

HPLC analyses of coenzyme extracts. (A) Wild-type M. thermoautotrophicum; (B) strain JA1. Cofactor isolation and HPLC analyses were performed as described in the text. The chemostat enrichment culture and the other mutant strains showed patterns similar to that in panel A.

DISCUSSION

Methanogenic members of the domain Archaea respond in a number of ways to changes in the supply of the energy source hydrogen. It has been known for quite some time that hydrogenotrophic methanogens, including M. thermoautotrophicum, the organism used in this study, partly uncouple growth from methane formation under conditions of high hydrogen availability (3, 7, 15, 17). In other words, growth yields tend to increase under hydrogen limitation. The rationale behind the hydrogen-dependent coupling and uncoupling is not understood. In addition, M. thermoautotrophicum appears to contain sets of isoenzymes and functionally equivalent enzymes in the central methanogenic pathway that are differentially expressed in response to variations in the hydrogen supply, in particular MCR I, MCR II, F420-MDH, and H2-MDH (7, 8, 10, 20). The differential expression is enhanced by other factors like the growth temperature, the medium pH, and the nature of the medium reductant (1, 9). It may be noted that the temperature and medium pH are, to an extent, related to the hydrogen potential. The solubility of the gas will be lower at higher temperatures. Moreover, according to the Nernst equation, the reducing power of hydrogen will depend on the pH (and temperature).

The complex adaptations described above presume the existence of a global regulatory mechanism or the presence of specific, cooperatively acting regulatory systems, whose nature(s) is still unknown. To elucidate the mechanism(s) underlying regulation of methanogenesis, mutants are indispensable. The aim of the present study was to develop a method for obtaining mutants that are defective in this regulation, in particular, mutants that had lost the ability to adapt to hydrogen-limited conditions. The method consisted of random mutagenesis, enrichment by chemostat culturing under the selective pressure of excess-hydrogen (MCR II) conditions, and subsequent selection of suitable clones on solid media. The reasoning behind the approach was the following. Mutants that due to modification of a regulatory element(s) fail to express, or that more or less completely down-regulate, the type of enzymes that are specifically required under hydrogen limitation (e.g., MCR I, F420-MDH) have a selective advantage over the wild type expressing those enzymes to some basic levels: no (or limited) energy has to be invested in their synthesis. An even minimal selective advantage is fully exploited during prolonged continuous culturing at high dilution rates. The consequence is that the mutants have to lose their ability to grow under low-hydrogen conditions.

By the method outlined, a number of stable mutants were obtained that, indeed, strictly required a high level of hydrogen for exponential growth. If this condition was not met by agitation of the cultures, no or only slow linear growth occurred. Another characteristic of the mutants was that if growth was permitted under hydrogen-limited conditions, their growth yields were significantly reduced (Table 1). Yields were especially low during stationary incubation at 68°C in MI medium, which represents the most hydrogen-limiting situation. In contrast, growth yields of wild-type M. thermoautotrophicum increase under hydrogen limitation (3, 7, 15, 17; also this study). The mutant strains, thus, at least seem to be affected in the (regulation of) coupling between growth and methanogenesis.

The finding that the mutants were unable to grow or to form methane under hydrogen limitation could imply that they lacked the appropriate methanogenic enzymes, notably, MCR I and F420-MDH. This idea is only partially supported by mRNA analyses (Table 2). In all except one of the mutants, MCR I and F420-MDH transcripts could be detected. Strain JB2, for example, which was able to down-regulate MCR I far below the levels of the wild type (Table 2), dramatically increased the mRNA levels of this enzyme and of F420-MDH in response to hydrogen limitation (Fig. 2). A comparison of the wild type and the mutants shows remarkable differences with respect to the contents and ratios of both MCRs and MDHs, indicating that the regulation of expression in the mutants was modified to an extent. The presence, however, of MCR I and F420-MDH does not offer an explanation for why the organisms were unable to grow under low-hydrogen conditions.

The most notable mutant is JA1. This strain showed only poor growth and poor growth yields. In addition, both F420-MDH and MCR I were absent, while the organism contained H2-MDH and MCR II. The absence of F420-MDH and MCR I represents, to our knowledge, the first example of mutagenic defects in the methanogenic machinery. Previous research involving mutants of methanogenic bacteria has been mainly restricted to auxotrophic mutants or resistance to antibiotics (4, 11, 16). The combination of defects suggests that the mutation must be located in a common regulatory element. Interestingly, strain JA1 was also unable to form factor F390. This factor has been suggested to act as a signal metabolite for hydrogen limitation and to operate in the regulation of expression (19–21). It may be noted that factor F390 is found in members of distantly related lineages like the families Methanobacteriaceae and the Methanosarcinaceae but is absent in members of the family Methanococcaceae, which represents a separate and very ancient branch within the methanogens (2, 5, 12, 18). The findings here that strain JA1 lacks the ability to synthetize factor F390 and fails to express both F420-MDH and MCR I lend further support to the hypothesis described above that the compound is involved in the regulation of hydrogen-dependent methanogenesis. However, this may be a partial answer to the regulation phenomenon. Additional or alternative mechanisms cannot be ruled out, especially in methanogens that lack factor F390.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The investigations of J.L.A.P. were supported by the Life Sciences Foundation, which is subsidized by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonacker L G, Baudner S, Thauer R K. Differential expression of the two methyl-coenzyme M reductases in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum as determined immunochemically via isoenzyme specific antisera. Eur J Biochem. 1992;206:87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J-F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Fuhrmann J L, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Roberts K M, Hurst M A, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H-P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fardeau M-L, Belaich J-P. Energetics of the growth of Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus. Arch Microbiol. 1986;144:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gast D A, Wasserfallen A, Pfister P, Ragettli S, Leisinger T. Characterization of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum Marburg mutants defective in regulation of l-tryptophan biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3664–3669. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3664-3669.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gloss L M, Hausinger R P. Methanogen factor 390 formation: species distribution, reversibility and effects of non-oxidative cellular stress. BioFactors. 1988;1:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris J E. GELRITE as an agar substitute for the cultivation of mesophilic Methanobacterium and Methanobrevibacter species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:1107–1109. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.4.1107-1109.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan R M, Pihl T D, Nölling J, Reeve J N. Hydrogen regulation of growth, growth yields, and methane gene transcription in Methanobacterium themoautotrophicum ΔH. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:889–898. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.889-898.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nölling J, Pihl T D, Vriesema A, Reeve J N. Organization and growth-phase-dependent transcription of methane genes in two regions of the Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum genome. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2460–2468. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2460-2468.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pennings J L A, de Wijs J L J, Keltjens J T, van der Drift C. Medium-reductant directed expression of methyl coenzyme M reductase isoenzymes in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (strain ΔH) FEBS Lett. 1997;410:235–237. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pihl T D, Sharma S, Reeve J N. Growth phase-dependent transcription of the genes that encode the two methyl coenzyme M reductase isoenzymes and N5-tetrahydromethanopterin:coenzyme M methyltransferase in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6384–6391. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6384-6391.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rechsteiner A, Kiener A, Leisinger T. Mutants of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1986;7:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeve J N, Nölling J, Morgan R M, Smith D R. Methanogenesis: genes, genomes, and who’s on first? J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5975–5986. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.5975-5986.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rospert S, Linder D, Ellermann J, Thauer R K. Two genetically distinct methyl-coenzyme M reductases in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum strain Marburg and ΔH. Eur J Biochem. 1990;194:871–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schönheit P, Moll J, Thauer R K. Nickel, cobalt, and molybdenum requirement for growth of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Arch Microbiol. 1979;123:105–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00403508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schönheit P, Moll J, Thauer R K. Growth parameters (Ks, μmax, Ys) of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Arch Microbiol. 1980;127:59–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00403508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanner R S, McInerney M J, Nagle D P. Formate auxotroph of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum Marburg. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6534–6538. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6534-6538.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsao J-H, Kaneshiro S M, Yu S-S, Clark D S. Continuous culture of Methanococcus jannaschii, an extremely thermophilic methanogen. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;43:258–261. doi: 10.1002/bit.260430309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Wijngaard W M H, Vermey P, van der Drift C. Formation of factor 390 by cell extracts of Methanosarcina barkeri. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2710–2711. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2710-2711.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermeij P, Detmers F J M, Broers F J M, Keltjens J T, van der Drift C. Purification and characterization of factor F390 synthetase from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (strain ΔH) Eur J Biochem. 1994;226:185–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vermeij P, Pennings J L A, Maassen S M, Keltjens J T, Vogels G D. Cellular levels of factor 390 and methanogenic enzymes during growth of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6640–6648. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6640-6648.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vermeij P, Vinke E, Keltjens J T, van der Drift C. Purification and properties of coenzyme F390 hydrolase from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (strain Marburg) Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:592–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.592_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]