Abstract

This study compares Medicare and patient spending for dual over-the-counter and prescription drugs with their over-the-counter cash prices.

Medicare Part D does not usually cover nonprescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. However, Medicare Part D prescription drug plans may cover OTC drugs when they are prescribed by a clinician and approved as prescription drugs by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patients can obtain these drugs using either Medicare coverage (prescription required) or OTC (pay cash; no prescription required).1,2 In June 2022, the FDA published guidance that may expand the number of such dual OTC and prescription drugs.3 We compared Medicare and patient spending for dual OTC and prescription drugs with their OTC cash prices, which, to our knowledge, has not been investigated previously.

Methods

The FDA’s Orange Book was used to identify drugs approved as both prescription and OTC as of November 1, 2022. A drug was defined as a combination of active ingredient, dosage form, and strength. Using Medicare Part D pharmacy claims data from a 20% national random sample of beneficiaries enrolled in traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage (excluding those who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and low-income subsidy recipients), we identified all 2020 claims for these drugs. We collected the OTC cash price for each drug on December 31, 2020, using the Amazon price tracker Keepa.com. If multiple vendors offered the same drug, the product with the highest number of reviews was chosen. The OTC cash price did not include shipping costs or sales taxes. Cash prices were transformed on a per-unit basis using the same units as Medicare (Supplement 1). We estimated Medicare Part D spending under cash prices by multiplying the number of units dispensed in Medicare Part D in 2020 by the OTC unit cash price and comparing it with the drug’s total 2020 spending (Medicare Part D spending plus patient out-of-pocket cost and third-party payments). For claims filled after the deductible phase (82% of claims), we compared the beneficiary out-of-pocket spending per unit with the OTC unit cash price to assess how frequently beneficiaries paid more with out-of-pocket costs than the drug’s cash price. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp).

Results

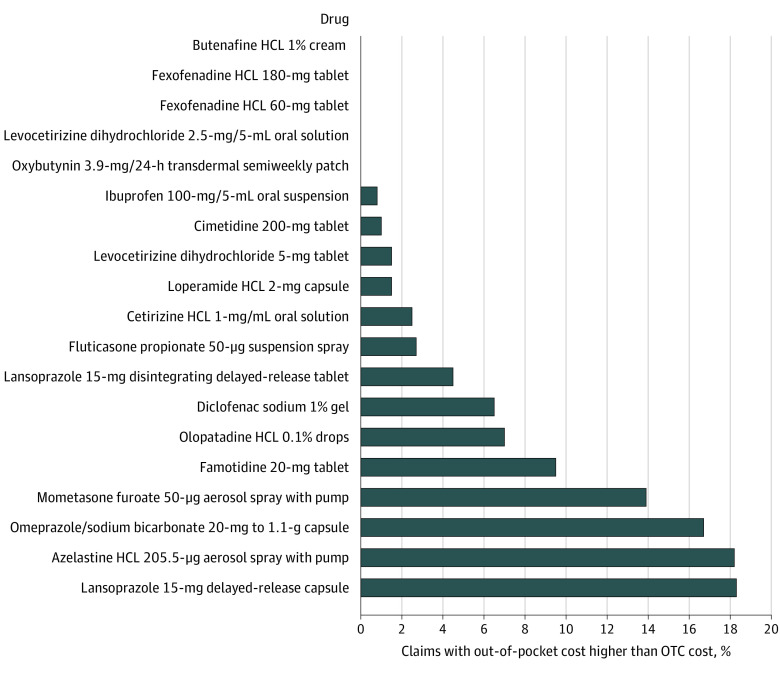

A total of 22 dual OTC and prescription drugs were identified, of which 20 drugs had Medicare claims in 2020 and 19 had OTC prices available. The 19 drugs represented 27 million claims and $716 million in spending in Medicare Part D in 2020 (Table). For 16 of the 19 drugs, OTC cash prices were lower than Medicare’s per-unit spending, with savings ranging from 10% to 97% per drug per year ($79 800 to $121 million). Overall, total spending could have been reduced by $406 million (57%) if the OTC cash price had been paid for all 19 drugs. After the deductible, beneficiaries paid more for the out-of-pocket costs than the cash price in 10% or more of the claims for 4 drugs: mometasone furoate 50 μg (13.9%); omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate 20 mg to 1.1 g (16.7%); azelastine hydrochloride 205.5 μg (18.2%); and lansoprazole 15 mg (18.3%) (Figure).

Table. Medicare and Over-the-Counter (OTC) Cash Price Comparisons.

| Druga | Pricing unit | Medicare Part D claims, No.b | Medicare Part D plans represented, %c | Medicare Part D unit price, $d | OTC unit price, $e | Total spending in Medicare Part D in 2020 in thousands, $d | Estimated spending under OTC price in thousands, $f | Medicare overspending in thousands, $g | Savings, %h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate 20-mg to 1.1-g capsule | 1 capsule | 18 640 | 15.2 | 27.85 | 0.80 | 25 328.70 | 730.82 | 24 597.88 | 97 |

| Mometasone furoate 50-μg aerosol spray with pump | 1 spray | 348 315 | 61.8 | 5.22 | 0.18 | 50 921.20 | 1739.64 | 49 181.56 | 97 |

| Lansoprazole 15-mg disintegrating delayed-release tablet | 1 tablet | 8885 | 13.5 | 10.61 | 0.38 | 3979.10 | 140.82 | 3838.28 | 96 |

| Oxybutynin 3.9-mg/24-h transdermal semiweekly patch | 1 patch | 3075 | 6.3 | 82.42 | 3.88 | 2962.10 | 139.26 | 2822.84 | 95 |

| Butenafine HCL 1% cream | 1 g | 525 | 4.3 | 5.67 | 0.47 | 114.5 | 9.42 | 105.08 | 92 |

| Azelastine HCL 205.5-μg aerosol spray with pump | 1 spray | 225 810 | 57.4 | 1.67 | 0.20 | 15 074.20 | 1804.84 | 13 269.36 | 88 |

| Levocetirizine dihydrochloride 2.5-mg/5-mL oral solution | 1 mL | 2220 | 7.1 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 199 | 36.23 | 162.77 | 82 |

| Olopatadine HCL 0.1% drops | 1 mL | 394 585 | 73.9 | 7.40 | 1.82 | 17 649.80 | 4330.90 | 13 318.90 | 75 |

| Famotidine 20-mg tablet | 1 tablet | 5 550 545 | 94.8 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 75 065.50 | 20 601.31 | 54 464.19 | 73 |

| Fexofenadine HCL 60-mg tablet | 1 tablet | 4920 | 8.0 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 114.9 | 35.06 | 79.84 | 69 |

| Fluticasone propionate 50-μg suspension spray | 1 spray | 11 867 240 | 97.0 | 0.73 | 0.30 | 207 252.00 | 86 250.19 | 121 001.81 | 58 |

| Lansoprazole 15-mg delayed-release capsule | 1 capsule | 101 500 | 49.3 | 0.83 | 0.40 | 5393.50 | 2625.58 | 2767.92 | 51 |

| Fexofenadine HCL 180-mg tablet | 1 tablet | 19 515 | 11.4 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 269.9 | 141.98 | 127.92 | 47 |

| Diclofenac sodium 1% gel | 1 g | 6 261 985 | 94.7 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 260 193.10 | 151 112.15 | 109 080.95 | 42 |

| Levocetirizine dihydrochloride 5-mg tablet | 1 tablet | 1 777 355 | 76.6 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 31 536.00 | 18 555.28 | 12 980.72 | 41 |

| Cimetidine 200-mg tablet | 1 tablet | 42 545 | 37.1 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 1677.00 | 1511.49 | 165.51 | 10 |

| Ibuprofen 100-mg/5-mL oral suspension | 1 mL | 19 235 | 27.6 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 493 | 493.00 | 0 | 0 |

| Loperamide HCL 2-mg capsule | 1 capsule | 659 085 | 82.8 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 17 935.40 | 19 607.01 | −1671.61 | −9 |

| Cetirizine HCL 1-mg/mL oral solution | 1 mL | 23 840 | 20.4 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 378.9 | 438.26 | −59.36 | −16 |

| Total | 1 unit | 27 329 820 | 44.2 | 716 538 | 310 303 | 406 235 | 57 |

Drugs were defined as a combination of active ingredient, dosage form, and strength; branded and generic products were considered the same drug.

Number of claims, number of units dispensed, and the total Medicare spending were obtained from Medicare Part D pharmacy claims data from a 20% national random sample of beneficiaries enrolled in traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage. The data were multiplied by a factor of 5 to approximate the total for the Medicare Part D Program.

The percentage of Part D plans reflects the number of different Medicare Part D prescription drug plans represented in the claims for each drug divided by the total number of plans available in 2020 (a total of 854 plans).

Medicare Part D prices reflect total spending (Medicare plan spending plus patient out-of-pocket cost plus any third-party payments) per unit of the drug (tablet/capsule, g, or mL).

OTC cash prices were obtained from the Amazon price tracker site Keepa (keepa.com) for December 31, 2020, except for azelastine and mometasone furoate, for which the earliest available prices were from August 2022. If multiple vendors were available for the same drug, the product with the highest number of reviews was chosen. The OTC cash price did not include shipping costs or sales taxes. Cash prices for OTC products were transformed to a per-unit basis using the same units recorded in the Medicare claims. See Supplement 1 for further details.

Medicare estimated spending under OTC cash prices was calculated by multiplying the number of units dispensed in Medicare Part D in 2020 by the OTC cash price per unit.

Medicare overspending was calculated by subtracting the estimated spending under OTC cash prices from the total spending in Medicare Part D in 2020. Negative values identify drugs for which the total spending in Medicare Part D was lower than the estimated spending under OTC cash prices.

Percentage savings were calculated as the Medicare overspending (or underspending) as a proportion of the actual total spending in Medicare Part D in 2020. The data do not include 2 drugs (fexofenadine hydrochloride [HCL] 30-mg tablets and ranitidine HCL 150-mg tablet) that did not have claims in Medicare Part D in 2020 and 1 drug (omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate 20- to 1680-mg packet) for which historic prices were not available.

Figure. Postdeductible Claims for Which Medicare Part D Beneficiary Out-of-Pocket Costs Were Greater Than Over-the-Counter Prices.

The number of claims and beneficiary spending were obtained from Medicare Part D pharmacy claims data from a 20% national random sample of beneficiaries enrolled in traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage. Beneficiaries who received a low-income subsidy or were eligible for Medicaid at any point during 2020 were excluded. Only claims that were filled after the deductible phase were included, to reflect claims where Medicare Part D coverage was applied. The included claims represented 82% of all claims for these drugs among included beneficiaries. Over-the-counter (OTC) cash prices were obtained from the Amazon price tracker site Keepa (keepa.com) for December 31, 2020, except for azelastine and mometasone furoate, whose earliest available prices were from August 2022. If multiple vendors were available for the same drug, the product with the highest number of reviews was chosen. The OTC cash price did not include shipping costs or sales taxes. Cash prices for OTC products were transformed to a per-unit basis using the same units recorded in the Medicare claims. Medicare beneficiary out-of-pocket cost per unit reflects total patient out-of-pocket cost divided by the total number of units dispensed for the drug in Medicare Part D in 2020. The data do not include 2 drugs (fexofenadine hydrochloride [HCL] 30-mg tablets and ranitidine HCL 150-mg tablet) that did not have claims in Medicare Part D in 2020 and 1 drug (omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate 20- to 1680-mg packet) for which historic prices were not available.

Discussion

Medicare Part D frequently paid more for dual OTC and prescription drugs than the OTC cash prices. Patients’ cost-sharing was sometimes higher than what they would pay for the same drug without insurance or a prescription. Limitations include that this study did not account for drug manufacturer rebates, which could potentially lower Medicare Part D’s net spending. However, rebates are typically not provided for generic drugs and do not reduce patients’ out-of-pocket costs.1 The calculated savings may be under- or overestimated because OTC cash prices can vary across different geographic areas and over the drug’s life cycle due to shortages and market fluctuations. The extent to which savings can be passed from plans to beneficiaries depends on the benefit design of each plan. The study sample may not have included all OTC drugs available through Medicare Part D. Sales taxes or shipping costs were not included, which would increase OTC prices.

Previous research showed the Medicare Part D Program overpaid for common generic drugs compared with prices available at large-scale retailers or the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company.4,5 However, those studies required that patients obtain a prescription to take advantage of the lower prices; this study shows that drugs could be available for less and without a prescription. For drugs available OTC, the Medicare Part D program should encourage plans to consider OTC cash prices when negotiating with manufacturers and require that pharmacies notify patients of cheaper OTC options.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Karen Lasser, MD, and Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editors.

eMethods

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Kang SY, Bai G, DiStefano MJ, Socal MP, Yehia F, Anderson GF. Comparative approaches to drug pricing. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:499-512. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapter 6: Part D Drugs and formulary requirements. In Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit Manual. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ; 2016. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Part-D-Benefits-Manual-Chapter-6.pdf

- 3.Nonprescription Drug Product with an Additional Condition for Nonprescription Use. US Food and Drug Administration ; 2022. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/06/28/2022-13309/nonprescription-drug-product-with-an-additional-condition-for-nonprescription-use

- 4.Trish E, Gascue L, Ribero R, Van Nuys K, Joyce G. Comparison of spending on common generic drugs by Medicare vs Costco Members. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(10):1414-1416. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lalani HS, Kesselheim AS, Rome BN. Potential Medicare Part D savings on generic drugs from the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Co. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(7):1053-1055. doi: 10.7326/M22-0756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Data sharing statement