Key Points

Question

Are local firework bans associated with reduced odds of firework-related ocular trauma?

Finding

This case-control study of 230 patients presenting with ocular trauma found that the odds of firework-related ocular trauma were slightly higher among residents of areas where fireworks were legal compared with those where fireworks were banned.

Meaning

This study suggests that local firework bans may be associated with a small reduction in the odds of firework-related ocular trauma.

Abstract

Importance

Fireworks can cause vision-threatening injuries, but the association of local legislation with the mitigation of these injuries is unclear.

Objective

To evaluate the odds of firework-related ocular trauma among residents of areas where fireworks are permitted vs banned.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This case-control study was conducted at a level 1 trauma center in Seattle, Washington, among 230 patients presenting with ocular trauma in the 2 weeks surrounding the Independence Day holiday, spanning June 28 to July 11, over an 8-year period (2016-2022).

Exposures

Firework ban status of patient residence.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Odds of firework-related injuries among residents of areas where fireworks are legal vs where they are banned, calculated as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs.

Results

Of 230 consultations for ocular trauma during the study period, 94 patients (mean [SD] age, 25 [14] years; 86 male patients [92%]) sustained firework-related injuries, and 136 (mean [SD] age, 43 [23] years; 104 male patients [77%]) sustained non–firework-related injuries. The odds of firework-related ocular trauma were higher among those living in an area where fireworks were legal compared with those living in an area where fireworks were banned (OR, 2.0 [95% CI, 1.2-3.5]; P = .01). In addition, the odds of firework injuries were higher for patients younger than 18 years (OR, 3.1 [95% CI, 1.7-5.8]; P < .001) and for male patients (OR, 3.3 [95% CI, 1.5-7.1]; P = .004). Firework injuries were more likely to be vision threatening (54 of 94 [57%]) compared with non–firework-related injuries (54 of 136 [40%]; OR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.2-3.5]; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

This case-control study suggests that the odds of firework-related ocular trauma were slightly higher among residents of areas where fireworks were legal compared with residents of areas where fireworks were banned. Although these results suggest that local firework bans may be associated with a small reduction in the odds of firework-related ocular trauma, additional studies are warranted to assess what actions might lead to greater reductions.

This case-control study evaluates the odds of firework-related ocular trauma among residents of areas where fireworks are permitted vs banned.

Introduction

Firework injuries in the US have increased in the past 15 years and disproportionately affect younger individuals.1,2 Ocular injuries account for 16% of firework-related US emergency department visits.2 An estimated 1840 firework-related ocular injuries occur per year in the US, most frequently near Independence Day.3 Internationally, firework celebrations occur frequently for New Year’s Eve4,5,6 and numerous other holidays, resulting in similar increases in ocular firework injuries during holidays and festival seasons in India,7,8,9,10 Nepal,11 China,12,13 Malaysia,14 Australia,15 and Switzerland.16,17,18 The severity of injury can range from mild irritation to open globe injuries with eventual enucleation.3,7,19

The demographic characteristics, type of injury, and firework type associated with these injuries have been well documented; firework-related ocular injuries primarily affect young males; frequently involve corneal burns, foreign bodies, and hyphemas; and occur most commonly due to firecrackers, bottle rockets, and sparklers.3,19,20 However, the association of legislation limiting the sale and use of fireworks with ocular injuries in the US is less well known. Studies conducted internationally have suggested higher incidences of ocular injuries in regions with more permissive fireworks policies (US and Hong Kong) compared with those with restrictive bans (Hungary and Ireland).20,21 Changes in legislation regarding firework restrictions have also been associated with a subsequent change in the incidence of firework-related ocular injury.12,22,23,24 However, in the US, the regulation of fireworks varies at the state, county, and municipal level, and legislation may be more difficult to study. Studies in the US have suggested an association between liberalized firework restrictions and firework-related injuries, but the results have not been conclusive.25,26,27

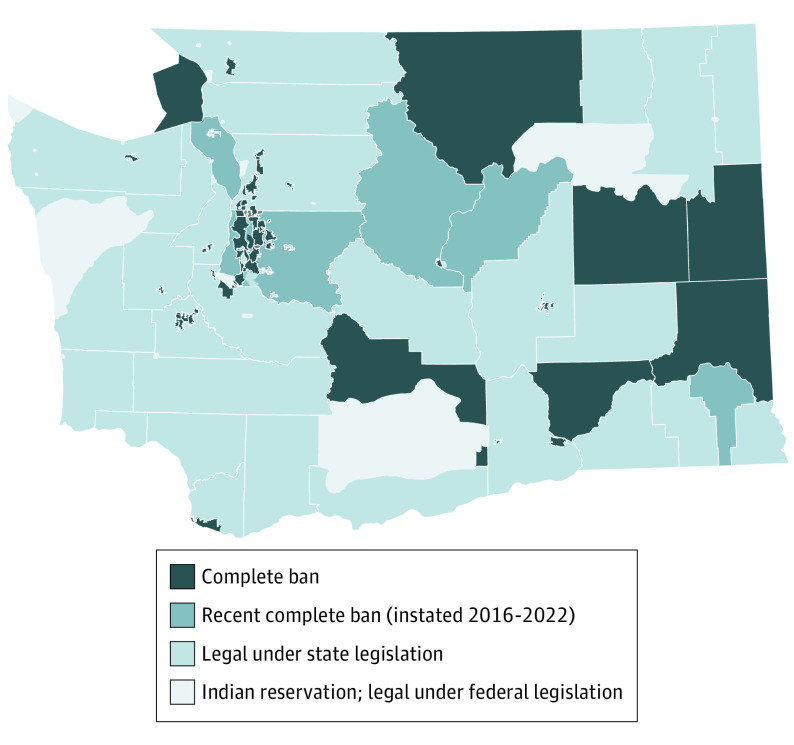

In Washington, state laws specify that certain fireworks are legal but restricted to June 28 through July 5 and to December 31 through January 1, with variable acceptable hours of discharge.28 However, each county and city may enact more restrictive legislation, with some municipalities and counties banning fireworks completely and others allowing them within state legislative restrictions (Figure 1). In addition, the sale and discharge of fireworks on federally recognized US Indian reservations are subject only to federal and tribal regulations, which are less restrictive than state legislation.29 With the geographic proximity of disparate local fireworks policies and the ability of consumers to travel to purchase fireworks in neighboring legislative districts, it is unclear whether local firework restrictions are effective in reducing firework-induced ocular trauma. Because local firework restrictions have been controversial in Washington state,30,31 we aim to assess whether local bans are associated with lower rates of firework-related ocular injury. Because most firework-related injuries in the US and at our institution occur near the Independence Day holiday,3,19 the 2-week period surrounding the Independence Day holiday was studied.

Figure 1. Firework Regulations in Washington State From 2016 to 2022.

The state map illustrates the variability among cities and counties in fireworks legislation.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective case-control study to evaluate the incidence of ocular trauma in the 2 weeks surrounding the Independence Day holiday, spanning June 28 to July 11, over an 8-year period (2016-2022) at a level 1 trauma center (Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Washington). This research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki32 and was approved by the University of Washington institutional review board. The institutional review board waived the need for informed consent because the research design of the study did not allow for consent to be obtained. This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Data were obtained from ophthalmology service call records, which documented after-hours consultations conducted in the emergency department between 5 pm and 8 am on weeknights and all day and night on weekends and holidays. Visits during daytime clinic hours were not included in the service call records.

All cases of ocular trauma were further categorized into firework-related and non–firework-related injuries. Non–firework-related injuries served as the control group. Ophthalmology consultations that were not trauma related were excluded. Medical record review was used to determine patient history, age, race and ethnicity (American Indian or Native Alaskan, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino/a or Latinx, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White [non-Hispanic or Latino/a or Latinx], ≥2 listed races, and unknown or declined to answer), sex, home address, nature of ocular injury, and visual acuity outcome at 1 year. The catchment area of the hospital system includes Washington, Alaska, Montana, Wyoming, and parts of Idaho and Oregon. For patients traveling from outside this region, the address of the transferring hospital was used. For each patient or transfer hospital address, a web search of firework bans was performed using local news sources, legislative documents, and city websites as the primary sources of information. Addresses located in areas in which fireworks could be purchased and discharged legally during the year of the hospital visit were defined as legal. Data regarding the location of purchase or discharge of fireworks were not recorded. Addresses located within an Indian reservation were also recorded. The 2010 Rural-Urban Community Area system33 was used to classify zip codes into regional classifications of urban (≥50 000), large town (10 000-49 999), small town (2500-9999), and rural (<2500).

All ocular injuries were categorized as vision threatening and non–vision threatening. Vision-threatening injuries included severe ocular burn, hyphema, dislocated lens, retinal or choroidal injury, open globe injury, intraocular foreign body, and orbital fracture requiring urgent surgical intervention. All other injuries, including eyelid injuries, minor corneal abrasion without evidence of limbal stem cell deficiency, corneal foreign body, corneal and conjunctival laceration without globe penetration, and orbital fracture not requiring immediate repair, were considered non–vision threatening. Visual acuity outcomes at 1 year were divided into 20/40 or better, 20/50 to 20/200, worse than 20/200, and unknown. Patients younger than 18 years were compared with those 18 years or older.

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism, version 9.5.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software). For categorical data, the Fisher exact test was used to examine the differences between firework-related injury cases and non–firework-related injury controls. Age was analyzed using a 2-tailed t test. All P values were 2-sided and were not adjusted for multiple analyses; results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CI were calculated to compare probabilities.

Results

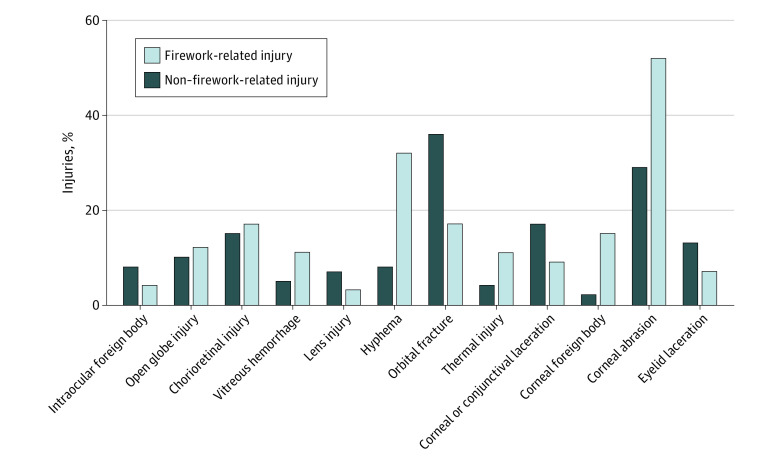

Of 500 total consultations during the study period, 230 were for ocular trauma. Of these, 94 patients (mean [SD] age, 25 [14] years; 86 male patients [92%]) sustained firework-related injuries, and 136 patients (mean [SD] age, 43 [23] years; 104 male patients [77%]) sustained non–firework-related injuries (Table 1). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Compared with non–firework-related trauma, odds of a firework injury were higher for male patients (OR, 3.3 [95% CI, 1.5-7.1]; P = .004) and for patients younger than 18 years (OR, 3.1 [95% CI, 1.7-5.8]; P < .001). Most ocular injuries occurred among patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (139 of 230 [60%]), followed by Hispanic or Latino/a or Latinx (40 of 230 [17%]) and Black (27 of 230 [12%]). There was no difference in race or ethnicity between the firework-related injury and non–firework-related ocular injury groups. For both firework-related and non–firework-related ocular injury groups, 84% resided in urban areas (firework-related injury, 79 of 94; non–firework-related injury, 114 of 136). Five percent (5 of 94) of firework-related injuries occurred among those residing in rural areas, and 1% of non–firework-related injuries (1 of 136) occurred among those living in rural areas (OR, 7.6 [95% CI, 1.0-89.9]; P = .04). The types of traumatic ocular injuries are shown in Figure 2. The most common firework-related injuries included corneal abrasion (49 of 94 [52%]), hyphema (30 of 94 [32%]), and corneal foreign bodies (14 of 94 [15%]) (Table 2). The most common non–firework-related injuries included orbital fractures (49 of 136 [36%]), corneal abrasion (40 of 136 [29%]), and conjunctival or corneal laceration (23 of 136 [17%]).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firework-related injury (n = 94) | Non–firework-related injury (n = 136) | |||

| Sex, self-reported | ||||

| Male | 86 (92) | 104 (77) | .004 | 3.3 (1.5-7.1) |

| Female | 8 (9) | 32 (24) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 25 (14) | 43 (23) | <.001 | NA |

| Aged <18 y | 33 (35) | 20 (15) | <.001 | 3.1 (1.7-5.8) |

| Race and ethnicity, self-reported | ||||

| American Indian or Native Alaskan | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | ≥.99 | 1.1 (0.3-4.1) |

| Asian | 4 (4) | 11 (8) | .29 | 0.5 (0.2-1.5) |

| Black or African American | 10 (11) | 17 (13) | .84 | 0.8 (0.4-2.0) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a or Latinx | 17 (18) | 23 (17) | .86 | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | .64 | 1.6 (0.3-10.6) |

| White (non-Hispanic or Latino/a or Latinx) | 59 (63) | 80 (59) | .58 | 1.2 (0.7-2.0) |

| ≥2 Listed races | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | .12 | 3.8 (0.8-19.2) |

| Unknown or declined to answer | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | ≥.99 | 0.7 (0.1-6.3) |

| Rural-urban classification | ||||

| Urban | 79 (84) | 114 (84) | .70 | 0.8 (0.4-1.8) |

| Large town | 7 (7) | 18 (13) | .20 | 0.5 (0.2-4.9 |

| Small town | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | .69 | 1.5 (0.3-6.4) |

| Rural | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | .04 | 7.6 (1.0-89.9) |

| Legality of fireworks at home address during year of injury | ||||

| Legal | 43 (46) | 40 (29) | .01 | 2.0 (1.2-3.5) |

| Banned | 51 (54) | 96 (71) | ||

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Figure 2. Ocular Injuries by Type for Firework-Related and Non–Firework-Related Injuries.

Many patients experienced more than 1 type of injury, and percentages do not add to 100%.

Table 2. Ocular Injury Type Among Firework-Related and Non–Firework-Related Injuries.

| Injury type | No. (%) | P value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firework-related injury (n = 94) | Non–firework-related injury (n = 136) | |||

| Vision threatening | 54 (57) | 54 (40) | .01 | 2.1 (1.2-3.5) |

| Injury type | ||||

| Eyelid laceration | 7 (7) | 13 (10) | .64 | 0.8 (0.3-1.8) |

| Corneal abrasion | 49 (52) | 40 (29) | <.001 | 2.6 (1.5-4.6) |

| Corneal foreign body | 14 (15) | 3 (2) | <.001 | 7.8 (2.2-25.8) |

| Corneal or conjunctival laceration | 9 (10) | 23 (17) | .12 | 0.5 (0.2-1.1) |

| Thermal injury | 10 (11) | 5 (4) | .05 | 3.1 (1.1-8.4) |

| Orbital fracture | 16 (17) | 49 (36) | .002 | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) |

| Hyphema | 30 (32) | 11 (8) | <.001 | 5.3 (2.5-11.7) |

| Lens injury | 3 (3) | 10 (7) | .25 | 0.4 (0.1-1.5) |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 10 (11) | 5 (4) | .05 | 3.1 (1.1-8.4) |

| Chorioretinal injury | 16 (17) | 20 (15) | .71 | 1.2 (0.6-2.5) |

| Open globe injury | 11 (12) | 13 (10) | .66 | 1.3 (0.6-3.0) |

| Intraocular foreign body | 4 (4) | 8 (6) | .77 | 0.7 (0.2-2.3) |

| Bilateral injury | 27 (29) | 27 (20) | .15 | 1.6 (0.9-3.0) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

The odds of firework-related ocular trauma were higher among those residing in an area where fireworks were legal compared with those in an area where fireworks were banned (OR, 2.0 [95% CI, 1.2-3.5]; P = .01) (Table 1). Among patients with firework-related injuries, 4 of 94 (4%) lived on Indian reservations, while 1 of 136 patients (1%) with non–firework-related injury lived on an Indian reservation (OR, 6.0 [95% CI, 1.0-73.2]; P = .17).

Firework-related injuries were more likely to be vision threatening (54 of 94 [57%]) compared with non–firework-related injuries (54 of 136 [40%]; OR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.2-3.5]; P = .01) (Table 2). There was no difference in the proportion of vision-threatening firework-related injuries between areas where fireworks were banned (29 of 51 [57%]) and areas where fireworks were legal (25 of 43 [58%]; OR, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.4-2.1]; P > .99). Among firework-related injuries, there were higher odds of corneal abrasion (49 of 94 [52%] vs 40 of 136 [29%]; OR, 2.6 [95% CI, 1.5-4.6]; P < .001), corneal foreign body (14 of 94 [15%] vs 3 of 136 [2%]; OR 7.8 [95% CI, 2.2-25.8]; P < .001), and hyphema (30 of 94 [32%] vs 11 of 136 [8%]; OR, 5.3 [95% CI, 2.5-11.7; P < .001) and lower odds of orbital fracture (16 of 94 [17%] vs 49 of 136 [36%]; OR, 0.4 [95% CI, 0.2-0.7]; P = .002) compared with non–firework-related injuries (Figure 2).

Of the 94 patients and 121 firework-related injured eyes, only 23 patients (25%), including 28 eyes (23%), had a follow-up appointment 1 year after the initial injury. Of the 121 affected eyes, 12 (10%) had a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better, 8 (7%) had a best-corrected visual acuity between 20/50 and 20/200, and 8 (7%) had a best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/200, including 2 (2%) with no light perception vision; 1-year follow-up visual acuity was not available for 93 of 121 (77%). Reasons for poor visual acuity at 1 year after injury included corneal scarring (2 eyes), severe open globe injury (2 eyes), macular hole (1 eye), glaucoma (1 eye), cystoid macular edema (1 eye), and amblyopia after firework-related cataract occurring at 5 months of age (1 eye).

Discussion

The results of this case-control study suggest that the odds of firework-related ocular trauma were slightly higher among residents of areas where fireworks were legal compared with those where fireworks were banned. However, these findings could be associated in part with confounding factors not associated with local fireworks bans. Additional studies would be needed to determine if local fireworks bans are effective in preventing ocular injuries, and even then, they may be limited due to the patchwork nature of such laws and the ability of residents to move freely between municipalities with differing fireworks laws. Such studies seem worthwhile because our data suggest that firework-related injuries may be more likely to be vision threatening and tend to occur among younger individuals compared with other ocular trauma.

Several prior studies have also detailed the vision-threatening nature of firework-related ocular injury among young individuals,3,12,19 and some studies have attempted to assess whether public health measures and legislative action were associated with the incidence of ocular firework injury (eTable in Supplement 1). Thygesen34 reported a decrease in the rate of ocular injuries associated with a preventative campaign in Denmark. Bull23 reported that providing free protective eyewear did not reduce the rate of ocular injury, but the ban on bottle rockets was associated with a 50% decrease in ocular injuries. Removal of a legislative ban in Northern Ireland was associated with an increase in the number of fireworks injuries,22 while implementing bans in large cities in Southern China may have been associated with a decrease in injuries the following year.12 Comparative analyses of the numbers of injuries between states26 and between nations20,21 have also demonstrated that nations with more restrictive firework legislation had a lower incidence of ocular firework injury. Beyond the ophthalmologic literature, Rudisill et al25 suggested a possible increase in firework-related injury after liberalization of state firework laws in West Virginia, and Galanis et al27 found a decrease in firework-related injuries in Honolulu associated with county policy changes limiting access to fireworks. As states, counties, and municipalities determine legislative restrictions on fireworks within the US, it is worthwhile to study the association of local fireworks regulations with firework-related ocular injury.

Over half the firework-related injuries in our study occurred among residents of areas where fireworks were banned. This finding suggests that restrictive local legislation does not eliminate the use of fireworks in these regions. However, our data are limited in that data regarding the location of purchase and discharge of fireworks were not available. Given the proximity of different legislative regions, it is possible that those living in regions with firework restrictions travel to nearby municipalities without firework restrictions to purchase and potentially discharge fireworks. Thus, we may be overestimating the amount of illegal firework use by using patient residence as a proxy for local firework laws. Despite this possibility, the results still demonstrate a greater proportion of firework-related injuries among residents of areas where fireworks are legal.

Limitations

This study has some limitations, including the single-center nature of the investigation. However, Harborview Medical Center is the only level 1 trauma center in its geographic region of the country. Although data may be subject to regional transfer biases, the control group of patients with traumatic ocular injuries likely reflects similar transfer biases. In addition, the date of purchase was not recorded, and thus, legislative bans on the date of purchase were unknown. The COVID-19 pandemic may also have been associated with study results due to a possible increase in the purchase and discharge of consumer fireworks in the setting of the cancellation of public fireworks displays.35 There were also relatively low numbers of injuries in total, with our case-control design limiting data collection to emergency department consultations seen on call over a 2-week period each year. Our data do not capture all firework-related ocular injuries seen at this institution, including those occurring on New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day or those occurring during clinic hours, so we are unable to report the incidence of firework injuries in our region. In addition, fewer than 25% of eyes had follow-up data available at 1 year, so interpretation of visual acuity outcomes is limited.

Conclusions

The design of this case-control study does not establish cause and effect but provides hypothesis-generating ideas to aid in future investigations of the association of legislation with the incidence of firework-related ocular injuries and vision-threatening ocular trauma. Further investigation could analyze statewide data or compare the data set with other states with or without firework restrictions.

Public health measures and education should be aimed toward limiting the use of fireworks among youths and young adults, given the higher proportion of injuries among younger patients. Legislation, including local bans, could be considered to decrease the morbidity of firework-related ocular trauma, and additional studies may determine what actions might lead to greater reductions in harm.

eTable. Review of Literature Regarding Firework-Related Ocular Injuries

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Moore JX, McGwin G Jr, Griffin RL. The epidemiology of firework-related injuries in the United States: 2000-2010. Injury. 2014;45(11):1704-1709. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith B, Pledger D. 2022. Fireworks annual report. United States Consumer Product Safety Commission. Published online June 2023. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/2022-Fireworks-Annual-Report.pdf

- 3.Shiuey EJ, Kolomeyer AM, Kolomeyer NN. Assessment of firework-related ocular injury in the US. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(6):618-623. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.0832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenglinger MA, Zorn M, Pilger D, et al. Firework-inflicted ocular trauma in children and adults in an urban German setting. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31(2):709-715. doi: 10.1177/1120672120902033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacu S, Ségur-Eltz N, Stenng K, Zehetmayer M. Ocular firework injuries at New Year’s Eve. Ophthalmologica. 2002;216(1):55-59. doi: 10.1159/000048298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apakama AI, Anajekwu CC. Ocular fireworks injuries in eastern Nigeria: a 3-year review. Niger J Surg. 2019;25(1):42-44. doi: 10.4103/njs.NJS_29_15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurien NA, Peter J, Jacob P. Spectrum of ocular injuries and visual outcome following firework injury to the eye. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2020;13(1):39-44. doi: 10.4103/JETS.JETS_62_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parija S, Chakraborty K, Ravikumar SR. Firework related ocular injuries in Eastern India—a clinico-epidemiological analysis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(12):3538-3544. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_753_21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John D, Philip SS, Mittal R, John SS, Paul P. Spectrum of ocular firework injuries in children: a 5-year retrospective study during a festive season in Southern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(11):843-846. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.171966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatesh R, Gurav P, Tibrewal S, et al. Appraising the spectrum of firework trauma and the related laws during Diwali in North India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(2):140-143. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_527_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malla T, Sahu S. Firework-related ocular injuries during festival season: a hospital-based study in a tertiary eye care center of Nepal. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2021;13(25):31-39. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v13i1.31246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang F, Lou B, Jiang Z, Yang Y, Ma X, Lin X. Changing trends in firework-related eye injuries in Southern China: a 5-year retrospective study of 468 cases. J Ophthalmol. 2020;2020:6194519. doi: 10.1155/2020/6194519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jing Y, Yi-qiao X, Yan-ning Y, Ming A, An-huai Y, Lian-hong Z. Clinical analysis of firework-related ocular injuries during Spring Festival 2009. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248(3):333-338. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1292-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rashid RA, Heidary F, Hussein A, et al. Ocular burns and related injuries due to fireworks during the Aidil Fitri celebration on the East Coast of the peninsular Malaysia. Burns. 2011;37(1):170-173. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Read DJ, Bradbury R, Yeboah E. Firework-related injury in the Top End: a 16-year review. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87(12):1030-1034. doi: 10.1111/ans.14182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frimmel S, Theusinger OM, Kniestedt C. Analysis of ocular firework-related injuries and common eye traumata: a 5-year clinical study. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2017;234(4):611-616. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-123515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turgut F, Bograd A, Jeltsch B, et al. Occurrence and outcome of firework-related ocular injuries in Switzerland: a descriptive retrospective study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22(1):296. doi: 10.1186/s12886-022-02513-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoskin AK, Low R, de Faber JT, et al. ; IGATES Fireworks study group . Eye injuries from fireworks used during celebrations and associated vision loss: the International Globe and Adnexal Trauma Epidemiology Study (IGATES). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;260(1):371-383. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05284-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang IT, Prendes MA, Tarbet KJ, Amadi AJ, Chang SH, Shaftel SS. Ocular injuries from fireworks: the 11-year experience of a US level I trauma center. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(10):1324-1330. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wisse RPL, Bijlsma WR, Stilma JS. Ocular firework trauma: a systematic review on incidence, severity, outcome and prevention. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(12):1586-1591. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.168419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhn FC, Morris RC, Witherspoon DC, et al. Serious fireworks-related eye injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7(2):139-148. doi: 10.1076/0928-6586(200006)721-ZFT139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan WC, Knox FA, McGinnity FG, Sharkey JA. Serious eye and adnexal injuries from fireworks in Northern Ireland before and after lifting of the firework ban—an ophthalmology unit’s experience. Int Ophthalmol. 2004;25(3):167-169. doi: 10.1007/s10792-004-1958-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bull N. Legislation as a tool to prevent firework-related eye injuries. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(8):e654-e655. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Faber JT, Kivelä TT, Gabel-Pfisterer A. National studies from the Netherlands and Finland and the impact of regulations on incidences of fireworks-related eye injuries. Ophthalmologe. 2020;117(1)(suppl 1):36-42. doi: 10.1007/s00347-019-00996-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudisill TM, Preamble K, Pilkerton C. The liberalization of fireworks legislation and its effects on firework-related injuries in West Virginia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8249-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson RS. Ocular fireworks injuries and blindness: an analysis of 154 cases and a three-state survey comparing the effectiveness of model law regulation. Ophthalmology. 1982;89(4):291-297. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(82)34789-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galanis DJ, Koo SS, Puapong DP, Sentell T, Bronstein AC. Decrease in injuries from fireworks in Hawaii: associations with a county policy to limit access. Inj Prev. 2022;28(4):325-329. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2021-044402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wisconsin State Legistature . RCW 70.77.395: dates and times consumer fireworks may be sold or discharged—local governments may limit, prohibit sale or discharge of fireworks. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=70.77.395

- 29.Washington State Office of the Attorney General . Indians–reservations–state fireworks law–sale of by enrolled members–maximum permit fee.(AGO 1962 No. 129 — May 4 1962). Accessed October 10, 2023. https://www.atg.wa.gov/ago-opinions/indians-reservations-state-fireworks-law-sale-enrolled-members-maximum-permit-fee

- 30.Hansen J. Firework sales stay legal in south county, even if you can’t light them. HeraldNet.com. Published July 27, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.heraldnet.com/news/firework-sales-stay-legal-in-south-county-even-if-you-cant-light-them/

- 31.Chastaine D. Contentious fireworks ban adopted in Covington. Covington-Maple Valley Reporter. Published December 11, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.covingtonreporter.com/news/contentious-fireworks-ban-adopted-in-covington/

- 32.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture . Rural-urban commuting area codes. Accessed October 15, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/

- 34.Thygesen J. Ocular injuries caused by fireworks: 25 years of experience with preventive campaigns in Denmark. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78(1):1-2. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078001001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.United States Consumer Product Safety Commission . Fireworks-related injuries and deaths spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed October 10, 2023. https://www.cpsc.gov/Newsroom/News-Releases/2021/Fireworks-Related-Injuries-and-Deaths-Spiked-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic?language=zh-hans

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Review of Literature Regarding Firework-Related Ocular Injuries

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement