Abstract

Background and objective

Polypharmacy is prevalent in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with severe disease. However, information on polypharmacy among COVID-19 patients who also suffer from cytokine storm is scarce. In light of this, the purpose of the present study was to assess the incidence of polypharmacy and in silico prediction of potential body proteins targeted by these drugs among hospitalized COVID-19 patients who were identified to have the additional burden of cytokine storm in the city of Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted from June 2021 to April 2022; the phenomena of major polypharmacy (six to nine medications) and excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications) were documented among 33 (15 males and 18 females) COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm during their hospital stay (8-45 days) in Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. The SwissTargetPrediction program was utilized in silico to predict and identify human body proteins that could be potentially targeted by selected medications involved in polypharmacy.

Results

All patients had tested positive for COVID-19 via PCR testing, and they showed different signs and symptoms of the disease. None of the patients recovered and all of them deceased. All 33 patients received many therapeutic agents that ranged in number from eight to 20/patient during their hospital stay. The mean number of medications was 15 ± 3. We identified 2/33 (6%) patients with major polypharmacy (eight and nine) and 31/33 (94%) with excessive polypharmacy (15.5 ± 2.7). The total number of medications identified in polypharmacy was 37, excluding vitamins, minerals, and intravenous solutions. The frequency of medications administered was as follows: antibiotics (67, 13.7%), mucolytic agents (56, 11.5%), corticosteroids (54, 11%), anticoagulants (48, 9.8%), antiviral agents (41, 8.4%), antihypertensive agents (32, 6.5%), analgesics (28, 5.7%), antifungal drugs (27, 5.5%), antidiabetics (26, 5.3%), and other medications (2-19, 0.41-3.9%). Using the SwissTargetPrediction program, various drugs including antiviral agents involved in polypharmacy were found to target, in silico, body proteins at a prediction percentage that ranged from 6.7% to 40%.

Conclusions

Major and extensive polypharmacy conditions were identified in hospitalized COVID-19 patients suffering from cytokine storm. The severity of COVID-19 with cytokine storm, comorbidities, and hospitalization were key factors associated with polypharmacy in the patients. The SwissTargetPrediction web server is useful for predicting in silico potential human body protein targets that could possibly be sources of additional information on the adverse/toxic effects of polypharmacy medications administered concurrently. Further research in current medication protocols prescribed for advanced COVID-19 illness with cytokine storm is warranted to gain deeper insights into the topic.

Keywords: target proteins, cytokine, extensive polypharmacy, multiple medications, coronavirus, sars-cov-2

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2), has led to a significant global health crisis [1-3]. While the disease primarily affects the respiratory system, it could also lead to dysfunction in several organ systems, including the heart, liver, kidneys, and immune system [1-3]. This contributed to significant morbidity and the loss of millions of lives worldwide [1-4]. In severe forms of the disease, COVID-19 patients can experience an overwhelming cytokine storm [5,6]. This condition of systemic hyperinflammation is characterized by an increase in the release of chemokines and cytokines, including interleukins such as interleukine-1 and interleukine-6, interferons, tumor necrosis factor, colony-stimulating factors, the chemokine family, and growth factors [5,6]. Subsequently, the cytokine storm contributes to systemic deterioration and toxicity, disrupting the tricarboxylic acid cycle in various organ systems of COVID-19 patients [6,7]. The deterioration of COVID-19 cases involved with cytokine storm increases the demand for multiple medications and subjects the patients to polypharmacy, which might worsen the situation even more and potentially induce drug-drug interactions [8-12].

Polypharmacy is clinically associated with severe illnesses in which the patient receives more than five medications [13,14]. Within this context, polypharmacy with its potential drug-drug interactions and/or drug side effects and toxicity vulnerability poses a serious threat and might even increase the mortality rate in COVID-19 patients, especially those in an advanced stage of the illness with the need to be hospitalized [15,16]. Several studies have reported that polypharmacy is globally prevalent in COVID-19 patients with increased morbidity and mortality rates [17-20]. This is especially true in the elderly and hospitalized COVID-19 patients needing long-term care and medications that eventually result in multiple drug therapy [18,19,21]. While polypharmacy has been documented in severe cases of COVID-19 [20-22], there is scarce information on its incidence among patients who suffer from the additional burden of cytokine storm, which requires even more medications [10,11]. The purpose of the present study was to assess the incidence of polypharmacy and in silico prediction of potential body proteins targeted by these drugs in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with concomitant cytokine storm in the city of Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and inclusion criteria

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted to examine the phenomenon of polypharmacy among COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm. A total of 165 COVID-19 patients of both genders were hospitalized at two hospitals in Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq (Duhok COVID-19, and Lalav Infectious Diseases Hospitals) from June 2021 to April 2022. The patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 based on nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swab collections, and the SARS-CoV-2 cases were confirmed by RNA extraction and real-time switch translation (RT)-PCR as per the WHO guidelines [23]. Of the 165 patients, 33 (15 males and 18 females) had severe COVID-19 clinical manifestations and they were diagnosed as having cytokine storm based on criteria including the worsening of the respiratory status and the three-fold elevation of at least two of the following markers: C-reactive protein, ferritin, D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase, and cardiac troponin [24]. The cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients was assessed and confirmed by the above-mentioned criteria and consensus among the infectious disease physicians at the hospitals mentioned above. The demographic characteristics of the 33 COVID-19 cytokine storm patients and their signs and symptoms during the hospital stay were recorded. COVID-19 patients without cytokine storm were excluded from the study.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval to conduct the present study was obtained from the Committee of Post Graduate Studies, College of Science, University of Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq, and from the Research Ethics Committee, Duhok Directorate General of Health, Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq (24102021-10-10, dated October 24, 2021). Written consent was obtained from patients recruited for the study. They were informed about the study's purpose, the nature of data collection, and the expected outcomes of the study. All the information about the patients and the collected data were kept confidential.

Polypharmacy

For the purpose of this study, polypharmacy was defined as hospitalized COVID-19 cytokine storm patients receiving at least five medications on admission and continuing as such during their hospital stay (8-45 days) [25,26]. Polypharmacy was further classified into major polypharmacy (six to nine medications) and excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications) [14]. The administration of medications to each patient was recorded, and the drugs were categorized according to their main clinical use and/or the expected outcomes, as follows: antibiotics, corticosteroids, mucolytic agents, anticoagulants, antipyretics/analgesics, antiviral agents, antidiabetics, proton pump inhibitors, antihypertensive agents, diuretics, anticholinergics, antacids, antipsychotics, sleep medications, antitussives, hypolipidemics, and pulmonary antifibrotic agents.

In silico prediction of human body protein targets by the drugs

We used the SwissTargetPrediction web server (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) to predict and identify potential protein targets, in the human body, of selected diverse medications involved in polypharmacy. This online tool forecasts human protein targets for medications and could potentially predict drug efficacy and/or adverse action or toxicity [27,28]. The SwissTargetPrediction online program accepts canonical Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILE) chemical structure formulae of drugs available at https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. Subsequently, these formulae were entered into the program in order to explore possible human body protein targets [27,28]. However, not all drug molecules are suitable for protein target prediction by the program because of the large molecular size limitations of some drugs such as insulin and vancomycin. The primary SwissTargetPrediction focus in the present study was on the antiviral agents remdesivir and favipiravir, which target, for example, the protease [29]. For the purpose of comparison, we selected eight additional drugs, with different structural formulae, as identified in the polypharmacy of the COVID-19 cytokine storm patients, to be subjected to SwissTargetPrediction analysis according to the availability of information in the program’s web server. A comprehensive SwissTargetPrediction review of all the 37 drugs listed in the present study was beyond the scope of the study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the data, and the statistical software PAST 4.13 was used for statistical analysis (https://www.nhm.uio.no/english/research/resources/past/).

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 33 COVID-19 patients included in the study. They were 15 (45.5%) males (42-91 years old) and 18 (54.5%) females (34-80 years old) with a mean duration of hospital stay of 21.1 ± 10 and 22.2 ± 10.7 days, respectively. They were mostly overweight to severely obese (23/33, 69.7%), and at the time of hospital admission, the patients had preexisting disease conditions, which were as follows: hypertension (21, 63.6%), type 2 diabetes (20, 60.6%), peptic ulcer (13, 39.4%) chronic cardiac disease (8, 24.2%), hematological diseases (8, 24.2%), and other conditions (two to six, 6.1%-18.2%) (Table 1). Ten (30.3%) patients were vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccines. All the patients had tested positive for COVID-19 via PCR testing, and they all showed different signs and symptoms of COVID-19 disease (Table 2). Unfortunately, none of the patients recovered and they all deceased.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of 33 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm.

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure therapy; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; SD: standard deviation

| Variables | Males | Females | Total |

| N (%) | 15 (45.5%) | 18 (54.5%) | 33 (100%) |

| Age, years, min-max | 42-91 | 34-80 | 34-91 |

| Duration of hospital stay, days, mean ± SD | 21.1 ± 10.0 | 22.2 ± 10.7 | 21.7 ± 10.2 |

| Duration of hospital stay, days, min-max | 12-45 | 8-42 | 8-45 |

| BMI, kg/m2, n (%) | |||

| Underweight | 2 (6.1%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Healthy weight | 3 (9.1%) | 4 (12.1%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| Overweight | 5 (15.2%) | 4 (12.1%) | 9 (27.3%) |

| Obese | 4 (12.1%) | 7 (21.2%) | 11 (33.3%) |

| Severely obese | 1 (3%) | 2 (6.1%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| CPAP requirement, n (%) | 15 (45.5%) | 18 (54.5%) | 33 (100%) |

| Preexisting medical conditions, n (%) | |||

| Type 2 diabetes | 9 (27.3%) | 11 (33.3%) | 20 (60.6%) |

| Arterial hypertension | 9 (27.3) | 12 (36.4%) | 21 (63.6%) |

| Chronic cardiac disease | 3 (9.1%) | 5 (15.2%) | 8 (24.2%) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2 (6.1%) | 4 (12.1%) | 6 (18.2%) |

| Bronchial asthma | 1 (3%) | 2 (6.1%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Peptic ulcer | 6 (18.2%) | 7 (21.2%) | 13 (39.4%) |

| Thyroid disorders | 3 (9.1%) | 2 (6.1%) | 5 (15.2%) |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 (3%) | 4 (12.1% | 5 (15.2%) |

| Hematological disorders | 2 (6.1%) | 6 (18.2%) | 8 (24.2%) |

| Cancer | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6.1%) |

| Vaccination, n (% ) | 6 (18.2%) | 4 (12.1%) | 10 (30.3%) |

| No vaccination, n (%) | 9 (27.3%) | 14 (42.4%) | 23 (69.7%) |

| Positive COVID-19 PCR test, n (%) | 15 (45.5%) | 18 (54.5%) | 33 (100%) |

| Polypharmacy, n (%) | |||

| Major polypharmacy (6-9 medications) | 2 (6%) | - | - |

| Excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications) | 31 (94%) | - | - |

| Outcome: deceased, n (%) | 15 (45.5%) | 18 (54.5%) | 33 (100%) |

Table 2. Signs and symptoms recognized in 33 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm.

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| Signs and symptoms | Males, n (%) | Females, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

| Fever | 14 (42.4%) | 17 (51.5%) | 31 (93.9%) |

| Cough | 9 (27.3%) | 9 (27.3%) | 18 (54.5%) |

| Chill | 3 (9.1%) | 5 (15.2%) | 8 (24.2%) |

| Sweating | 1 (3%) | 4 (12.1%) | 5 (15.2%) |

| Dry mouth | 5 (15.2%) | 5 (15.2%) | 10 (30.3%) |

| Chest tightness | 14 (42.4%) | 18 (54.5%) | 32 (97%) |

| Chest pain | 14 (42.4%) | 13 (39.4%) | 27 (81.8%) |

| Shortness of breath | 15 (45.5%) | 18 (54.5%) | 33 (100%) |

| Headache | 5 (15.2%) | 9 (27.3%) | 14 (42.4%) |

| Nausea | 8 (24.2%) | 11 (33.3%) | 19 (57.6%) |

| Vomiting | 3 (9.1%) | 4 (12.1%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (18.2%) | 4 (12.1%) | 10 (30.3%) |

| Stomachache | 13 (39.4%) | 13 (39.4%) | 26 (78.8%) |

| Loss of appetite | 11 (33.3%) | 16 | 27 (81.8%) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (12.1%) | 5 (15.2%) | 9 (27.3%) |

| Constipation | 7 (21.2%) | 5 (15.2%) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Epigastric pain | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Myalgia | 15 (45.5%) | 16 (48.5%) | 31 (93.9%) |

| Joints pain | 6 (18.2%) | 4 (12.1%) | 10 (30.3%) |

| Fatigue | 15 (45.5%) | 18 (54.5%) | 33 (100%) |

| Loss of taste (ageusia) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Bitter taste | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6.1%) |

| Loss of smell (anosmia) | 5 (15.2%) | 5 (15.2%) | 10 (30.3%) |

All 33 patients received several therapeutic agents that ranged in number from eight to 20/patient during their hospital stay, which ranged from eight to 45 days (Table 3). The mean number of polypharmacy medications/patient was 15 ± 3 with a median of 14 (Table 4). We identified 2/33 (6%) patients with major polypharmacy (eight and nine) and 31/33 (94%) with excessive polypharmacy (15.5 ± 2.7) (Tables 1, 3, 4). The total number of medications included in the polypharmacy was 37, excluding vitamins, minerals, and intravenous solutions (Table 4). The frequency of medications administered to the patients is shown in Table 4, which was as follows: antibiotics (67, 13.7%), mucolytic agents (56, 11.5%), corticosteroids (54, 11%), anticoagulants (48, 9.8%), antiviral agents (41, 8.4%), antihypertensive agents (32, 6.5%), analgesics (28, 5.7%), antifungal drugs (27, 5.5%), and antidiabetics (26, 5.3%). The frequency of administration of other medications ranged from two to 19 (0.41-3.9%).

Table 3. Medications administered to 33 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm.

*Major polypharmacy (6-9 medications); excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications)

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| Patient no. | Medications administered | No. of medications* |

| 1 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, fluconazole, bromhexine, amlodipine, valsartan | 12 |

| 2 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, famotidine, bromhexine, budesonide, ipratropium bromide, fluconazole, furosemide, insulin | 14 |

| 3 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, heparin, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, haloperidol, melatonin, amlodipine, valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide, insulin, atorvastatin, omeprazole, bromhexine, spironolactone | 19 |

| 4 | Remdesivir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, dexamethasone, enoxaparin, budesonide, amlodipine, valsartan, insulin, atorvastatin | 11 |

| 5 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, ipratropium bromide, fluconazole, nystatin, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, bromhexine, theophylline, montelukast, ivy leaf product | 17 |

| 6 | Remdesivir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, insulin | 8 |

| 7 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, famotidine, melatonin, amlodipine, valsartan, insulin, atorvastatin, enoxaparin, bromhexine, albumin, esomeprazole | 18 |

| 8 | Remdesivir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, bromhexine, enoxaparin, omeprazole, albumin | 15 |

| 9 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, fluconazole, nystatin, clopidogrel, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, ivy leaf product, omeprazole, albumin, furosemide | 17 |

| 10 | Remdesivir, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, heparin, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, clopidogrel, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, montelukast, theophylline, bromhexine, omeprazole | 17 |

| 11 | Remdesivir, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, clopidogrel, insulin, bromhexine, omeprazole | 13 |

| 12 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, famotidine, fluconazole, bromhexine, enoxaparin, omeprazole, bisoprolol, pirfenidone | 14 |

| 13 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, ipratropium bromide, fluconazole, clopidogrel, haloperidol, furosemide, insulin, bromhexine, enoxaparin, acetaminophen, omeprazole, albumin, atorvastatin, spironolactone | 20 |

| 14 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, amlodipine, valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide, insulin, atorvastatin, bromhexine | 14 |

| 15 | Remdesivir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, bromhexine | 11 |

| 16 | Remdesivir, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, ipratropium bromide, haloperidol, enoxaparin, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, bromhexine | 14 |

| 17 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, enoxaparin, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, haloperidol, melatonin, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, omeprazole, bromhexine, spironolactone | 17 |

| 18 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, rivaroxaban, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, famotidine, budesonide, fluconazole, furosemide, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, enoxaparin, bromhexine, pirfenidone | 19 |

| 19 | Remdesivir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, budesonide, ipratropium bromide, haloperidol, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, bromhexine | 14 |

| 20 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, famotidine, melatonin, amlodipine, valsartan, insulin, atorvastatin, bromhexine, enoxaparin, acetaminophen, albumin, esomeprazole | 18 |

| 21 | Remdesivir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, insulin, bromhexine, enoxaparin, omeprazole, albumin | 13 |

| 22 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, heparin, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, amlodipine, montelukast, theophylline, fluconazole, bromhexine | 13 |

| 23 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, famotidine, bromhexine, budesonide, montelukast, theophylline, ipratropium bromide, fluconazole, furosemide, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin | 19 |

| 24 | Remdesivir, meropenem, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, fluconazole, bromhexine, enoxaparin, albumin, esomeprazole | 9 |

| 25 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, montelukast, theophylline, enoxaparin, budesonide, ipratropium bromide, esomeprazole | 11 |

| 26 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, fluconazole, nystatin, clopidogrel, enoxaparin, amlodipine, valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide, insulin, atorvastatin, ivy leaf product, omeprazole, albumin, furosemide | 20 |

| 27 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, enoxaparin, apixaban, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, famotidine, nystatin, omeprazole, albumin | 14 |

| 28 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, heparin, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, clopidogrel, insulin, theophylline, bromhexine, omeprazole, montelukast | 16 |

| 29 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, famotidine, budesonide, ipratropium bromide, fluconazole, clopidogrel, bromhexine, albumin | 14 |

| 30 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, vancomycin, levofloxacin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, enoxaparin, acetylcysteine, budesonide, fluconazole, clopidogrel, amlodipine, insulin, atorvastatin, montelukast, theophylline, bromhexine, omeprazole | 18 |

| 31 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, fluconazole, nystatin, clopidogrel, insulin, enoxaparin, ivy leaf product, omeprazole, albumin, furosemide | 15 |

| 32 | Remdesivir, meropenem, vancomycin, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, famotidine, melatonin, insulin, bromhexine, albumin, enoxaparin, acetaminophen, esomeprazole | 14 |

| 33 | Remdesivir, favipiravir, meropenem, vancomycin, acetaminophen, heparin, methylprednisolone, acetylcysteine, famotidine, bromhexine, budesonide, ipratropium bromide, fluconazole, furosemide, amlodipine, valsartan, insulin, atorvastatin | 18 |

Table 4. Frequency of medications administered to 33 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm.

Vitamins, minerals, and intravenous solutions were not included in the polypharmacy

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| Medication | Frequency/33 patients | Medication classes | Frequency/33 patients | % of total frequencies (489) |

| Meropenem | 26 | Antibiotics | 67 | 13.7 |

| Vancomycin | 22 | |||

| Levofloxacin | 19 | |||

| Acetylcysteine | 30 | Mucolytic agents | 56 | 11.5 |

| Bromhexine | 26 | |||

| Methylprednisolone | 32 | Corticosteroids | 54 | 11.0 |

| Dexamethasone | 4 | |||

| Budesonide | 18 | |||

| Heparin | 14 | Anticoagulants (Antithrombotic, Antiplatelet agents) | 48 | 9.8 |

| Enoxaparin | 23 | |||

| Rivaroxaban | 1 | |||

| Apixaban | 1 | |||

| Clopidogrel | 9 | |||

| Remdesivir | 27 | Antiviral agents | 41 | 8.4 |

| Favipiravir | 14 | |||

| Amlodipine | 20 | Antihypertensive agents | 32 | 6.5 |

| Valsartan | 8 | |||

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 3 | |||

| Bisoprolol | 1 | |||

| Acetaminophen | 28 | Analgesics/Antipyretics | 28 | 5.7 |

| Fluconazole | 22 | Antifungal agents | 27 | 5.5 |

| Nystatin | 5 | |||

| Insulin | 26 | Antidiabetics | 26 | 5.3 |

| Esomeprazole | 5 | Proton pump inhibitors | 19 | 3.9 |

| Omeprazole | 14 | |||

| Atorvastatin | 19 | Statin | 19 | 3.9 |

| Albumin | 12 | Plasma protein | 12 | 2.5 |

| Furosemide | 8 | Diuretics | 11 | 2.25 |

| Spironolactone | 3 | |||

| Ivy leaf product | 4 | Antitussives | 11 | 2.25 |

| Theophylline | 7 | |||

| Famotidine | 10 | H2 Blocker | 10 | 2.04 |

| Ipratropium bromide | 9 | Anticholinergics | 9 | 1.84 |

| Montelukast | 7 | Leukotriene receptor blocker | 7 | 1.43 |

| Haloperidol | 5 | Antipsychotics | 5 | 1.02 |

| Melatonin | 5 | Sleep regulators | 5 | 1.02 |

| Pirfenidone | 2 | Antifibrotic agents | 2 | 0.41 |

| Total | 489 | - | 489 | 100 |

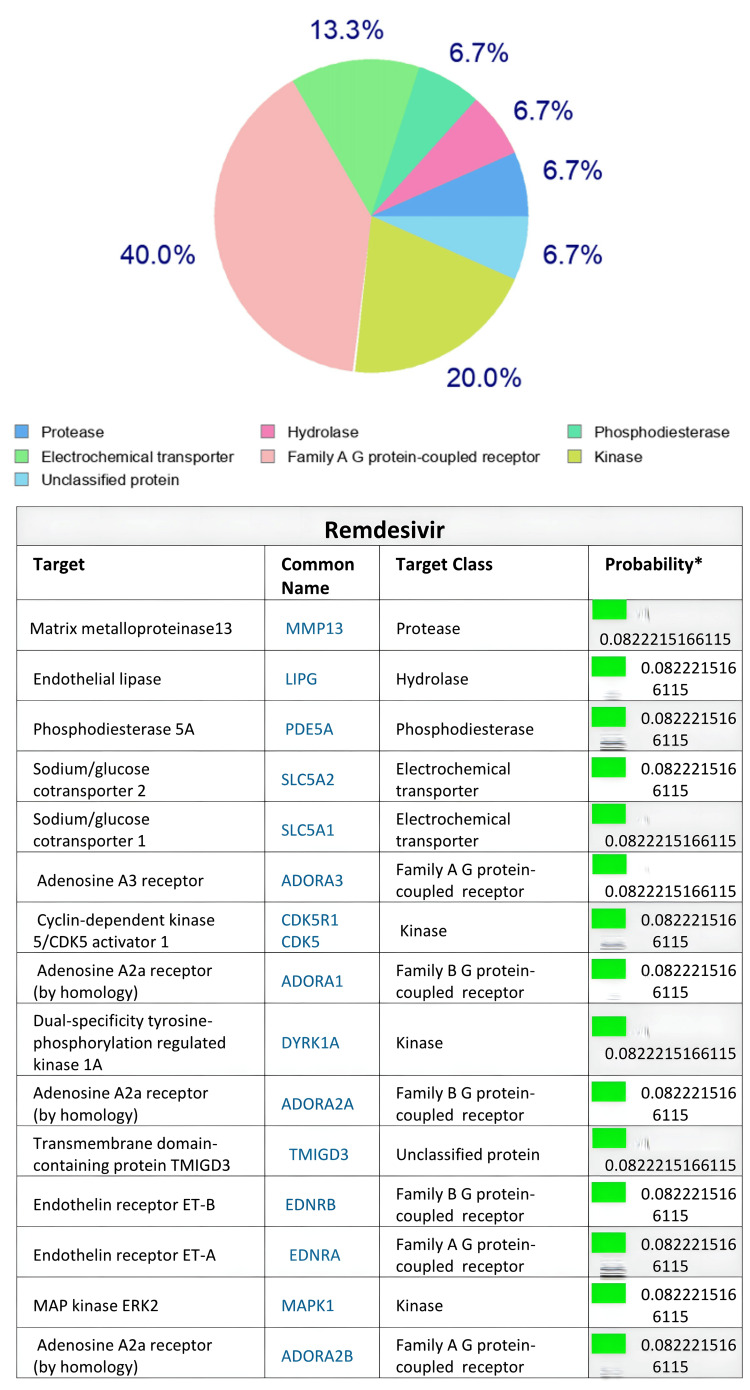

Based on the SwissTargetPrediction program, the human body proteins targeted by the two antiviral agents remdesivir and favipiravir after in silico evaluation are illustrated in Figures 1-2, respectively. Remdesivir targeted A-G receptor protein (40%), kinase (20%), and electrochemical transporter, followed by protease, hydrolase, phosphodiesterase, and unclassified protein (6.7% each) at p=0.0822 (Figure 1). On the other hand, favipiravir target classes included lyase (40%), hydrolase (13.3%), purine nucleoside phosphorylase (13.3%) and kinase, writer, proteases, and voltage-gated ion channels (6.7% each) at p=0.0439 (Figure 2). Examining eight other drugs included in the polypharmacy with the aid of SwissTargetPrediction for potential protein targets in the body indicated that these drugs target proteins to varying extents ranging from 6.7% to 40% (Tables 5, 6).

Table 5. In silico SwissTargetPrediction web server prediction of human body protein targets by various medications involved in polypharmacy recorded in COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm.

Detailed target outputs for remdesivir and favipiravir are presented in Figures 1-2. For a complete list of polypharmacy medications, see Tables 3-4

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| Protein targets | % of proteins targeted by medications | |||

| Meropenem | Levofloxacin | Acetylcysteine | Prednisolone | |

| Family AG protein-coupled receptor | 33.3 | 26.7 | 13.3 | 6.7 |

| Kinase | 20 | 6.7 | - | - |

| Protease | 26.7 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| Lyase | 13.3 | - | - | - |

| Eraser | - | 26.7 | 33.3 | 13.3 |

| Cytochrome P450 | - | - | - | 6.7 |

| Phosphodiesterase | - | 13.3 | - | - |

| Unclassified | - | - | - | - |

| Enzyme | - | 13.3 | 26.7 | - |

| Fatty acid-binding protein | - | - | - | 6.7 |

| Isomerase | - | - | - | - |

| Other cytosolic protein | - | - | - | - |

| Adhesion | - | - | - | - |

| Ligase | - | - | - | 6.7 |

| Oxidoreductase | - | 6.7 | - | - |

| Secreted protein | - | - | - | 20 |

| Electrochemical transferase | 6.7 | - | - | - |

| Hydrolase | - | - | - | - |

| Transferase | - | - | - | - |

| Writer | - | - | - | - |

| Voltage-gated ion | - | - | - | - |

| Phosphatase | - | - | 20 | 6.7 |

| Primary active transporter | - | - | - | - |

| Nuclear receptor | - | - | - | 26.7 |

Table 6. In silico SwissTargetPrediction web server prediction of human body protein targets by various medications involved in polypharmacy recorded in COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm.

Continuation of Table 5

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| Protein targets | % of proteins targeted by medications | |||

| Enoxaparin | Acetaminophen | Fluconazole | Omeprazole | |

| Family AG protein-coupled receptor | - | - | - | 6.7 |

| Kinase | - | - | 33.3 | 26.7 |

| Protease | 6.7 | - | 6.7 | 13.3 |

| Lyase | 13.3 | 40 | 13.3 | - |

| Eraser | - | - | - | 20 |

| Cytochrome P450 | - | 6.7 | 13.3 | - |

| Phosphodiesterase | - | - | - | 6.7 |

| Unclassified | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.7 | - |

| Enzyme | - | 33.3 | 20 | 13.3 |

| Fatty acid-binding protein | - | - | - | - |

| Isomerase | 6.7 | - | 6.7 | - |

| Other cytosolic protein | 26.7 | - | - | - |

| Adhesion | 26.7 | - | - | - |

| Ligase | - | - | - | - |

| Oxidoreductase | 26.7 | - | - | - |

| Secreted protein | 6.7 | - | - | - |

| Electrochemical transferase | - | - | - | - |

| Hydrolase | - | - | - | - |

| Transferase | - | 13.3 | - | 6.7 |

| Writer | - | - | - | - |

| Voltage-gated ion | 6.7 | - | - | - |

| Phosphatase | - | - | - | - |

| Primary active transporter | - | - | - | 6.7 |

| Nuclear receptor | - | - | - | - |

Figure 1. In silico SwissTargetPrediction web server prediction (%) of remdesivir’s human body protein targets .

Figure 2. In silico SwissTargetPrediction web server prediction (%) of favipiravir’s human body protein targets.

Discussion

The COVID-19 patients included in the present study, who were suffering from cytokine storm with signs and symptoms of the disease, were hospitalized for varying durations (8-45 days). Being in such a critical condition, the patients were administered various therapeutic agents to combat the disease and its signs and symptoms, since a definitive cure for COVID-19 is not available [8-12]. However, not all the drugs were COVID-19-specific, as the patients were suffering from comorbidities, which can be characterized as a multimorbidity condition (Table 1), which demands additional medications. The COVID-19 patients in the present study eventually died during their hospital stay. This could be attributed in a collective manner to the severity of their condition [2,3,15,16], possible drug-drug interactions [18,19], complications exerted by the cytokine storm [5,10,11], as well as comorbidities and ineffectiveness of therapy [3,15-20]. These factors altogether quite possibly paved the way for polypharmacy in COVID-19 cytokine storm patients in the present study. However, we were not able to identify the benefit(s), if any, of multi-therapy in the COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm as all of them unfortunately deceased.

The types of polypharmacy identified in the present study were classified as major (6%) and excessive (94%). Similarly, polypharmacy findings have been reported by other investigators in COVID-19 patients with varying degrees of severity of the illness as well as comorbid conditions [15-20]. It certainly appears that hospitalization [16], old age [21], and the severity of COVID-19 illness [22] are the major factors that predispose patients to polypharmacy. The present study is unique in that we describe polypharmacy in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm, a condition that itself needs special care and additional supportive therapy [5,10,11], thereby increasing the possibility of extensive polypharmacy. Antibiotics were the most prevalent class of medications received by the COVID-19 patients in the present study. This finding aligns with another report showing elevated usage of antimicrobials in COVID-19 patients [19] because of the severity of the illness. It should be emphasized that polypharmacy is not solely linked to COVID-19 as many treatments of other acute or chronic illnesses potentially result in polypharmacy with adverse consequences [13,14].

Drug-drug interactions and subsequent adverse/toxic effects of the polypharmacy medications might occur in COVID-19 patients [8,12,15,16,18,19]. In the present study, we applied the SwissTargetPrediction online tool to detect protein targets in the human body that possibly interact with selected polypharmacy medications (including the antiviral agents) administered to COVID-19 patients. The SwissTargetPrediction findings, though not sufficiently comprehensive to include all the 37 medications reported in the present study, point to potential target body proteins shared by the polypharmacy drugs. The drugs administered to COVID-19 patients could possibly target these sites to produce adverse effects or even toxicity [28,29]. The SwissTargetPrediction analysis revealed that the antiviral agents, remdesivir and favipiravir used in COVID-19 patients in the present study, share common target proteins with other medications involved in the polypharmacy. These target proteins of remdesivir and favipiravir predicted by the SwissTargetPrediction included varying targeting percentages of A-G receptor protein, kinase, electrochemical transporter, protease, hydrolase, phosphodiesterase, lyase, hydrolase, purine nucleoside phosphorylase, writer, proteases, and voltage-gated ion channels classes. The target proteins predicted by SwissTargetPrediction for medications found in the polypharmacy group (Tables 5, 6) shared similar and additional target proteins, raising the possibility of adverse or toxic interactions (at the level of body proteins) of antiviral drugs with other medications co-administered to patients due to their critical conditions as a result of COVID-19 with cytokine storm. However, not all the medications shared similar targets, as predicted for acetaminophen (Table 6). Nevertheless, the SwissTargetPrediction tool could be an additional useful tool for drug-drug interaction used to predict possible adverse drug interaction/reactions in polypharmacy studies [13,14,29,30]. Further in silico and in vitro studies are warranted to explore the possibility of such interactions more deeply.

Limitations of the study

Adverse effects and toxicity of medications involved in polypharmacy that could have adversely affected the outcome were not determined in patients. We did not explore the possibility of drug-drug interaction using other drug-interaction programs. The benefits, if any, of multi-therapy in COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm could not be identified. Not all polypharmacy medications were subjected to STP, and a few were not accepted by the program, because of large molecular size or structural limitations.

Conclusions

Major and extensive polypharmacy conditions were identified in hospitalized COVID-19 patients suffering from cytokine storm, and the beneficial effects of the therapeutic agents administered were unclear since all the patients died. The severity of COVID-19 with cytokine storm and comorbidities that needed hospitalization were key factors causing major and extensive polypharmacy conditions in these patients. The SwissTargetPrediction web server is a versatile tool for identifying and predicting in silico potential human body protein targets that could possibly be sources for information on additional adverse/toxic effects related to polypharmacy medications administered concurrently. We recommend further research on current medication protocols prescribed for advanced COVID-19 cases, especially those with the cytokine storm.

Acknowledgments

This report constitutes a portion of a dissertation to be submitted by the first author to the College of Science, University of Duhok, Iraq in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree in Toxicology. The authors thank the Colleges of Pharmacy and Science, University of Duhok for their support and for providing facilities and supplies to conduct this study.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Fouad K. Mohammad, Ghazwan A. Raouf, Muayad A. Merza

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Fouad K. Mohammad, Ghazwan A. Raouf, Muayad A. Merza

Drafting of the manuscript: Fouad K. Mohammad, Ghazwan A. Raouf, Muayad A. Merza

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Fouad K. Mohammad, Ghazwan A. Raouf, Muayad A. Merza

Supervision: Fouad K. Mohammad, Muayad A. Merza

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Research Ethics Committee, Duhok Directorate General of Health, Duhok, Kurdistan Region, Iraq issued approval 24102021-10-10, dated October 24, 2021

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.Clinical update on COVID-19 for the emergency clinician: presentation and evaluation. Long B, Carius BM, Chavez S, Liang SY, Brady WJ, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;54:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Zhang JJ, Dong X, Liu GH, Gao YD. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2023;64:90–107. doi: 10.1007/s12016-022-08921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.High mortality rates among COVID-19 intensive care patients in Iraq: insights from a retrospective cohort study at Médecins Sans Frontières supported hospital in Baghdad. Malaeb R, Haider A, Abdulateef M, et al. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1185330. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1185330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harnessing the immune system to overcome cytokine storm and reduce viral load in COVID-19: a review of the phases of illness and therapeutic agents. Khadke S, Ahmed N, Ahmed N, et al. Virol J. 2020;17:154. doi: 10.1186/s12985-020-01415-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cytokine storm induced by SARS-CoV-2. Song P, Li W, Xie J, Hou Y, You C. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;509:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic changes of vital organs in SARS-CoV-2-induced systemic toxicity. Li S, Ma F, Yokota T, et al. JCI Insight. 2021;6:3–7. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.145027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The development of COVID-19 treatment. Yuan Y, Jiao B, Qu L, Yang D, Liu R. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1125246. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1125246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An overview on the treatments and prevention against COVID-19. Panahi Y, Gorabi AM, Talaei S, Beiraghdar F, Akbarzadeh A, Tarhriz V, Mellatyar H. Virol J. 2023;20:23. doi: 10.1186/s12985-023-01973-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Immunopathogenesis and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19. Kim JS, Lee JY, Yang JW, et al. Theranostics. 2021;11:316–329. doi: 10.7150/thno.49713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Interleukin-6 blocking agents for treating COVID-19: a living systematic review. Ghosn L, Assi R, Evrenoglou T, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;6:0. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013881.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An overview of the safety assessment of medicines currently used in the COVID-19 disease treatment. Javorac D, Grahovac L, Manić L, et al. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;144:111639. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Recognizing and managing polypharmacy in advanced illness. Talebreza S, McPherson ML. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:230. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The impact of polypharmacy on 30-day COVID-related mortality in nursing home residents: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Visser AG, Winkens B, Schols JM, Janknegt R, Spaetgens B. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s41999-022-00723-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Exploring the associations between polypharmacy and COVID-19-related hospitalisations and deaths: a population-based cohort study among older adults in Quebec, Canada. Sirois C, Boiteau V, Chiu Y, Gilca R, Simard M. BMJ Open. 2022;12:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global prevalence of polypharmacy among the COVID-19 patients: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ghasemi H, Darvishi N, Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Akbari H, Mohammadi M. Trop Med Health. 2022;50:60. doi: 10.1186/s41182-022-00456-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evaluation of potential drug-drug interactions and polypharmacy in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Kilit TP, Özyiğit F, Erarslan S, Onbaşı K. Afr Health Sci. 2022;22:597–606. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v22i4.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potential for drug interactions and polypharmacy from treatment of COVID-19 in long-term care. Blaszczyk AT, Sandlin K, Mirza S, Hernandez L, Bader H, Hall RG. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23:949–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polypharmacy among COVID-19 patients: a systematic review. Iloanusi S, Mgbere O, Essien EJ. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2021;61:0–25. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The double burden of the COVID-19 pandemic and polypharmacy on geriatric population - public health implications. Rahman S, Singh K, Dhingra S, et al. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:1007–1022. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S272908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Relation of severe COVID-19 to polypharmacy and prescribing of psychotropic drugs: the REACT-SCOT case-control study. McKeigue PM, Kennedy S, Weir A, et al. BMC Med. 2021;19:51. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01907-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Global surveillance for COVID-19 disease caused by human infection with novel coronavirus (COVID-19): interim guidance, 27 February. [ Nov; 2023 ]. 2020. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/331231 https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/331231

- 24.Preliminary predictive criteria for COVID-19 cytokine storm. Caricchio R, Gallucci M, Dass C, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:88–95. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross-sectional observational study on association of polypharmacy with health-related quality of life in patients with hypertension. Paramba T, Zilate S. Cureus. 2022;14:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.In-silico analysis on potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 protease agents by structure-based docking and cheminformatics. Tiraihi T, Absalan A. http://mjms.modares.ac.ir/article-30-52853-en.html MJMS. 2021;24:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:0–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.In silico identification of new anti-SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) molecules with pharmacokinetic properties from natural sources using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and hierarchical virtual screening. Onyango H, Odhiambo P, Angwenyi D, Okoth P. J Trop Med. 2022;2022:3697498. doi: 10.1155/2022/3697498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Identification of possible SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: in silico molecular docking and dynamic simulation studies. Mukherjee A, Pandey KM, Ojha KK, Sahu SK. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2023;12:69–70. [Google Scholar]