Abstract

Background:

Following onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, chronic kidney disease (CKD) clinics in BC shifted from established methods of mostly in-person care delivery to virtual care (VC) and thereafter a hybrid of the two.

Objectives:

To determine strengths, weaknesses, quality-of-care delivery, and key considerations associated with VC usage to inform optimal way(s) of integrating virtual and traditional methods of care delivery in multidisciplinary kidney clinics.

Design:

Qualitative evaluation.

Setting:

British Columbia, Canada.

Participants:

Patients and health care providers associated with multidisciplinary kidney care clinics.

Methods:

Development and delivery of semi-structured interviews of patients and health care providers.

Results:

11 patients and/or caregivers and 12 health care providers participated in the interviews. Participants reported mixed experiences with VC usage. All participants foresaw a future where both VC and in-person care was offered. A reported benefit of VC was convenience for patients. Challenges identified with VC included difficulty establishing new therapeutic relationships, and variable of abilities of both patients and health care providers to engage and communicate in a virtual format. Participants noted a preference for in-person care for more complex situations. Four themes were identified as considerations when selecting between in-person and VC: person’s nonmedical context, support available, clinical parameters and tasks to be completed, and clinic operations. Participants indicated that visit modality selection is an individualized and ongoing process involving the patient and their preferences which may change over time. Health care provider participants noted that new workflow challenges were created when using both VC and in-person care in the same clinic session.

Limitations:

Limited sample size in the setting of one-on-one interviews and use of convenience sampling which may result in missing perspectives, including those already facing challenges accessing care who could potentially be most disadvantaged by implementation of VC.

Conclusions:

A list of key considerations, aligned with quality care delivery was identified for health care providers and programs to consider as they continue to utilize VC and refine how best to use different visit modalities in different patient and clinical situations. Further work will be needed to validate these findings and evaluate clinical outcomes with the combination of virtual and traditional modes of care delivery.

Trial registration:

Not registered.

Keywords: virtual care, multidisciplinary clinic, telemedicine, team-based care, COVID-19

Abrégé

Contexte:

Après le début de la pandémie de COVID-19, les cliniques d’insuffisance rénale chronique (IRC) de la Colombie-Britannique sont passées d’une prestation de soins traditionnelle fondée principalement sur les visites en personne à des soins en mode virtuel, puis à un modèle hybride combinant les deux méthodes.

Objectifs:

Déterminer les avantages et les faiblesses des soins en mode virtuel, ainsi que la qualité de la prestation des soins et les principaux facteurs à considérer relativement à l’utilization des soins en mode virtuel, afin d’informer sur les meilleurs moyens d’intégrer les méthodes virtuelles et traditionnelles de prestation des soins dans les cliniques multidisciplinaires de néphrologie.

Conception:

Évaluation qualitative.

Cadre:

Colombie-Britannique (Canada).

Sujets:

Patients et prestataires de soins associés à des cliniques multidisciplinaires de soins rénaux.

Méthodologie:

Élaboration et réalisation d’entrevues semi-structurées auprès de patients et de prestataires de soins de santé.

Résultats:

En tout, 11 patients et/ou soignants et 12 prestataires de soins de santé ont participé aux entrevues. Les participants ont fait état d’expériences mitigées avec les soins en mode virtuel. Tous les participants envisageaient un futur où les soins seront offerts tant en mode virtuel qu’en personne. Un des avantages mentionnés des soins en mode virtuel est la commodité pour les patients. Parmi les défis mentionnés figuraient la difficulté à établir de nouvelles relations thérapeutiques et les capacités variables des patients et des prestataires de soins de santé à établir une relation et à communiquer en mode virtuel. Les participants ont noté une préférence pour les soins en personne dans les situations plus complexes. Quatre thèmes ont été identifiés comme facteurs à prendre en compte dans le choix entre les soins virtuels ou en personne: le contexte non médical de la personne, l’aide disponible, les paramètres cliniques et les tâches à accomplir, et les opérations de la clinique. Les participants ont indiqué que le choix de la modalité pour les visites est un processus individualisé et continu impliquant le patient et ses préférences, lesquelles peuvent changer au fil du temps. Les prestataires de soins ont indiqué que le fait d’offrir à la fois des soins virtuels et en personne dans une même séance clinique créait de nouveaux défis en matière de flux de travail.

Limites:

La taille limitée de l’échantillon pour les entrevues individuelles et l’utilization d’un échantillonnage de commodité pourraient avoir manqué certains points de vue, notamment celui de personnes déjà confrontées à des difficultés d’accès aux soins et qui pourraient être les plus désavantagées par la mise en œuvre de soins en mode virtuel.

Conclusion:

Une liste de facteurs-clé à prendre en compte pour une prestation de soins de qualité a été établie à l’attention des prestataires de soins de santé et des programs qui continuent à utiliser les soins en mode virtuel, et décrit la meilleure façon d’utiliser les différentes modalités de visites dans différentes situations cliniques et pour différents patients. D’autres travaux seront nécessaires pour valider ces résultats et évaluer les résultats cliniques lorsqu’il y a combinaison des modes virtuel et traditionnel pour la prestation des soins.

What was known before

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a need to rapidly shift from established in-person care delivery methods, first via virtual CKD care delivery and thereafter an ongoing hybrid of in-person and virtual care modalities.

What this adds

This evaluation identifies strengths and weaknesses of the different visit modalities available, as well as a list of key considerations, aligned with quality care delivery for health care providers and programs to consider as they determine how best to use these different visit modalities in the variety of patient and clinical situations encountered in multidisciplinary CKD care.

Introduction

Nondialysis chronic kidney disease (CKD) care is complex, and many jurisdictions address this complexity through multidisciplinary clinics founded on an existing evidence and experience base.1,2 At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many jurisdictions responded with a rapid shift to mostly virtual care (VC) delivery initially, with strategies to integrate virtual and in-person care developed and integrated thereafter. 3 VC in this setting refers to any situation where a patient is not physically present, including encounters by phone or video-enabled platforms. While this transition was a necessary safety measure at the time, 3 this substantial shift in care delivery was not the result of a planned change or program of work focused on a desired endpoint, but rather a response to an emergent public health crisis.

Prior to the pandemic, in British Columbia (BC) Canada, multidisciplinary kidney care clinic (KCC) teams traditionally met with patients, and where appropriate family members/ care partners, in a physical clinic setting which allows for physical contact and examination, and enables the nuanced conversations and shared decision-making involved in kidney care.1,2 The ability of the team to understand each patient’s unique values and goals of care is integral in optimizing patient-centered CKD care and is dependent on quality interactions between patients and care providers.1,2,4 With the rapid shift to largely virtual models implemented in a variety of methods in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is unclear if the existing model of multidisciplinary care or the foundational high-quality patient and provider interactions were preserved.

Previously reported experiences with VC implementation in kidney care and other care settings largely describe the feasibility of implementing virtual solutions,5-10 access and/or user acceptability of virtual tools.8-12 There are limited data on the quality of these care interactions across the spectrum of different visit modalities and types of clinical interactions involved in multidisciplinary CKD care. Furthermore, many of the previously mentioned studies focus on the implementation of a single VC service model in comparison to in-person clinic services, but not the integration of the two, which was the real-world response to the COVID-19 pandemic.3,13

It is not known how these changes in care delivery and the transition to a hybrid of VC and in-person CKD care have impacted patient outcomes or patient, health care provider and team experiences with the delivery of kidney care. It is also unknown how to integrate new and traditional models of care delivery most effectively across diverse clinical settings and the spectrum of CKD care. To this end, we have developed a sequential multiphase, mixed-methods evaluation to examine the implementation, integration and quality of care delivery associated with the method(s) of virtual kidney care delivery in BC KCCs 14 with the goal of discerning considerations that will inform the optimal way(s) to integrate virtual and traditional modes of care delivery. This report describes the results of the qualitative phase of this evaluation which aims to understand patient and health care provider perspectives of VC usage, integration, and impact on multidisciplinary CKD care.

Methods

Study Setting and Interview Design

This qualitative study is part of a larger evaluation for which a detailed description has previously been published. 14 At the time, phone was the most used visit format with most of the clinics in BC reporting using phone for over half of their visits. Home-based video visits were the second most used visit type, and were provided by approximately half of the KCCs, with most of those providing a small proportion of their virtual visits this way. All clinics reported that at that time in-person visits made up less than a quarter to half of all visits.

A working group was formed to guide the design and execution of the qualitative study; this group consisted of two kidney health professionals (MB and JW), a project manager (YM), a quality improvement specialist (HC), two representatives from BC’s Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA) Office of Virtual Health (OVH) (MM, JW, MF, and DS at different times through the project lifespan), and two patient partners with lived experience of CKD care in BC KCCs (PW and AL). The working group developed two sets of interview questions, one for patients/caregivers and the other for health care providers. The sets of interview questions were tested (YM and HC) and modified at the beginning of the study to ensure face validity.

The working group used existing evaluation frameworks where possible to inform this tailored evaluation approach. Two frameworks used heavily were and BC Renal’s (BCR) internal evaluation framework 15 and the BC Health Quality Matrix. 16 The BC Health Quality Matrix is a tool developed by the BC Patient Safety and Quality Council that has been widely used across diverse care settings in BC to evaluate health care services by defining and evaluating discrete domains that contribute to quality of care (Table 1).

Table 1.

Components of the BC Health Quality Matrix.

| Dimension of quality care delivery | Perspective | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Respect | Individual | Honoring a person’s choices, needs and values |

| Safety | Avoiding harm and fostering security | |

| Accessibility | Ease with which health and wellness services are reached | |

| Appropriateness | Care that is specific to a person’s or community’s context | |

| Effectiveness | Care that is known to achieve intended outcomes | |

| Equity | System | Fair distribution of services and benefits according to population need |

| Efficiency | Optimal and sustainable use of resources to yield maximum value |

Source. Adapted from BC Health Quality Matrix. 17

Note. BC = British Columbia.

Participants, Recruitment, and Interview Methods

Kidney health professionals in KCCs, as well as patients and family caregivers who had lived experience of KCC care and had both in-person and virtual (phone, home-based video, or facility-based video) visits in KCCs in BC, Canada, since November 2019 were invited to participate. Recruitment was by convenience sampling. The opportunity to participate was broadly promoted to all KCC patients and health care providers across the provincial kidney network through various communication channels, posters placed in clinics and targeted emails to clinic managers and leaders to encourage participation of their staff and recruitment of patient participants. For patients/caregivers, surveys and interviews were offered in English, Punjabi and Cantonese, which are the most frequently encountered languages in BC KCCs.

Both patient/caregiver and health care provider interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews performed by a combination of 4 team members (HC, MF, BL, and YM). Interviewers used the same set of core interview questions (Supplement 1) with additional optional questions at the discretion of the interviewer. Interviews were offered via either phone or home-based videoconference options and were conducted from June to October 2021. Due to restrictions at the time, in-person interviews were not offered. Recruitment sample size was guided via a thematic saturation approach that was monitored throughout the process with the intent of halting recruitment when saturation was reached. None of the interviewers had any prior relationship with any of the participants.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were then coded and analyzed using NVivo 12 (QSR International, Burlington, MA) by one author (HC). To monitor for diversity in voices and theme saturation, data analysis was initiated as the transcripts became available to guide further recruitment efforts. In conceptualizing the impact of using different visit modalities during the pandemic and the key considerations in discerning the use of various in-person and virtual visit modality options, a 3-step thematic process that includes data condensation, displaying and conclusion drawing for the qualitative analysis was adopted. 17

The coding guide for this data condensation was iteratively developed; specifically, descriptive codes based on the interview questions were used to initiate the analytical process and the code guide was further built with emergent codes that were derived from the data itself. Furthermore, the data analysis includes alignment of considerations to the dimensions of quality in the BC Health Quality Matrix. 16 As recurring patterns emerged from the coding, patterns were detected and grouped together to create meaningful themes. This analytical process allowed the themes to be systematically refined based on the data until data saturation was reached when no new themes were identified in subsequent interviews. Three study team members with different perspectives (patient partner, BC Renal and PHSA Office of Virtual Health staff; HC, PD and PW) were involved in the final qualitative analysis with independent close readings of the transcripts, note-taking and interpretation. Key themes and representative quotes for each theme were selected through consensus by this team. Where there were discrepancies, the coding was re-visited by HC, followed by further discussion and refinement among the triad until consensus was reached. To support rigor in reporting of the final results, the COREQ checklist for reporting of qualitative research was utilized. 18

Results

A total of 23 volunteers participated in the interviews: 11 patients and/or caregivers and 12 health care providers. All participants who provided consent completed the interviews and all were completed in 1 session. Self-reported characteristics of patient/caregiver and health care provider participants are outlined in Table 2. Between the two groups, there was at least 1 participant from each of the 15 BC KCCs and for the health care providers, all professional disciplines were represented. One patient interviewee opted to be interviewed in Cantonese, with the rest of the interviews occurring in English.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics.

| Patient/caregiver | Health care providers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 11 | N | 12 |

| Patient | 9 | Gender | |

| Family/caregiver | 2 | Men | 0 |

| Gender | Women | 12 | |

| Men | 2 | Gender diverse | 0 |

| Women | 8 | Experience in kidney care clinic (years) | |

| Gender diverse | 1 | <5 | 2 |

| Age (years) | 5-10 | 5 | |

| 20-39 | 2 | 11-15 | 1 |

| 40-59 | 1 | >15 | 4 |

| 60-79 | 8 | Role | |

| 80+ | 0 | Physician | 2 |

| Distance from home to kidney clinic | Nurse | 4 | |

| <10 km | 5 | Dietitian | 2 |

| 10-50 km | 5 | Social worker | 2 |

| >50 km | 1 | Pharmacist | 2 |

| Experience with visit modalities a | Experience with visit modalities a | ||

| In-person | 10 | In-person | 12 |

| Phone | 4 | Phone | 12 |

| Home-based video | 3 | Home-based video | 8 |

| Facility-based video | 1 | Facility-based video | 7 |

Participants were instructed to consider the visit modalities they had experienced in the previous 12 months. Home-based video refers to video visits conducted by the patient at home, whereas facility-based video refers to situations where patients travel to a designated health care delivery site to attend the visit.

Two major categories of responses were identified: (1) Impact of VC integration on patient and care provider kidney care experiences and (2) key considerations for the selection of visit modalities.

Impact of VC Integration on Patient and Care Provider Kidney Care Experiences

3 major themes were identified from interviewee responses: (1) user (patient and health care provider) experiences with virtual tools, (2) clinical relationships between patients and health care providers, and (3) patient access to KCC team members and team member access to patients. These themes and representative quotes are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Impact of Virtual Care Integration on Patient and Care Provider Kidney Care Experiences.

| Themes | Selected patient/caregiver comments | Selected health care provider comments |

|---|---|---|

| User experience with virtual tools | “<For in-person visit> you do a lot of sitting and waiting to see each person. You talk to one, and then you go back and sit in the waiting room and wait for the next one. And there’s always quite a few people at clinic. So usually takes a couple of hours that you’re there just to see all the different people, whereas it takes much less time on the phone.”—patient (PP3) “They’ve also changed in the way that you would go in for your care clinic in person prior to pandemic, and you would see all four people bang, bang, bang, bang. With this, it’s a little bit more broken up depending on people’s availability on the phone. So you would maybe talk to one or two people, and then someone else would call you back. Then the nephrologist would usually call several hours after that . . .”—patient (PP5) |

“I’m starting to enjoy my practice again. It’s taken a long time. It’s working in a variety of cases of just staying connected to people. I think there’s going to be some changes in the relationship and potentially some changes in our ability to educate people well.”—nephrologist (HCP10) “How has it affected me as a clinician, I think it’s been difficult, to be honest. I think it’s not so much that any one way of seeing patients is particularly difficult, but I think the fact of doing the visits in so many different modalities, switching between them—often even within one clinic—it is taxing that there’s a certain amount of added—let’s call it—emotional load from just switching and that aspect of it.”—social worker (HCP8) |

| Clinical relationships between patients and care team members | “It’s sometimes hard to understand emotions over the Zoom or the phone.”—patient (PP2) “How do we keep consistent with the same people getting the same information would be really helpful. Like when assigning a patient to a doctor in that clinic, you will always attend that clinic. Because we’ve seen all three [KCC team members], and we’ve got three different sets of answers and three different assessments.”—family caregiver (FP1) |

“Because our relationships are long-term . . . it’s important to be able to build rapport and establish that trusting relationship and [it’s] very, very difficult to do over the phone. First of all, you have no sense of who a person is. What they look like is a big part of building a relationship. So, you’re not able to build that trust.—pharmacist (HCP7) “If we already have a relationship established, then it seems to work okay with these virtual formats. I find that I can still get reasonable information if I’m asking questions in a different way and asking more questions.”—nephrologist (HCP4) |

| Patient access to KCC team members and team member ability to interact with patients | “I’ve only seen a social worker once, and that was the first visit I ever had at the kidney clinic, which is probably six years ago. It wasn’t offered at all, and it’s sort of never been offered since. From time to time I’ve thought . . . especially during the pandemic, everyone’s feeling a little down and a little bewildered by life. It might have been a good idea to talk to a social worker at least once during that period. But it never came up. Once again, in a personal visit I could just say, can I see the social worker? And the person’s right there.”—patient (PP1) | I think what I get worried about is when you do your conversations, especially with patients who either lack the health literacy, or maybe the fact that English is not their first language . . . I think that’s where you kind of get worry of, “Are they providing me the right information?” . . . [When] you’re worried that they have such symptoms, and you ask them, “How is your blood pressure,” and they don’t check it . . . You’re kind of worried, “If this person were to come in, I could’ve checked it . . . Same thing with patients, for example, who, when you ask them if they have edema . . . you can’t assess edema over a telephone . . . So, I think it’s also not knowing what the patient has at home to provide the accurate information that we would’ve received or we would’ve obtained in the in-person appointments.—nurse (HCP1) |

| Other key priorities identified | “I don’t live far from the hospital but to get up, go there, find parking, go in, sit and wait . . . it’s definitely a lot handier just to fire up my computer and get it over and done with.”—patient (PP2) | “I like the flexibility (of being) able to work from home a few days a week, (and) save the transportation times. Also, some patients, they don’t answer calls unless we call them in the evening time—like, 7:00—and then I think working from home, I do have a flexibility for patients.”—nurse (HCP2) |

Note. Numbers in parentheses indicate participants. PP = patient participant; HCP = health care provider; KCC = kidney care clinic; FP = family participant.

In terms of user experience, patients generally provided positive feedback for reduced travel associated with virtual visits. Beyond that, feedback was mixed among patients and family caregivers; for example, some of them missed human contact when they could not have in-person visits, and some felt overwhelmed with instructions for home-based video visits while others had good experiences.

Both patient and health care provider participants alluded to the importance of an established therapeutic relationship between the patient and their KCC team in enabling optimal kidney care in any format. It was suggested that VC was more effective when established relationships had been formed from previous in-person visits while for newer patients, health care providers found it harder to build rapport and trust virtually than in-person. From the health care provider perspective, some participants indicated difficulties reaching and/or engaging some patients in a virtual format, often requiring multiple attempts to connect.

Regarding clinic operations, health care providers described a learning curve at the beginning when they had to establish new workflows to set up phone and home-based video visits with patients and establish new ways to communicate with other KCC team members who may or may not be in the same physical location. Several also noted increased workload and stress while juggling the changes and multiple workflows associated with offering different visit types. Participants noted a shift in how clinic visits were conducted; for example, with virtual visits it was reported that rather than patients visiting with all providers consecutively as with an in-person visit, different KCC team members interacted with patients at different times on the same day or sometimes over multiple days which some patients reported as a disadvantage. Some patients mentioned that they were unable to connect with one or more KCC members during virtual visits.

Key Considerations for the Selection of KCC Visit Modalities

Participants foresaw a future of using both in-person and virtual visit options in KCCs. When asked, none of the health care provider participants reported a standardized method used in their clinics to assist with selection of visit types but rather did so on a case-by-case basis.

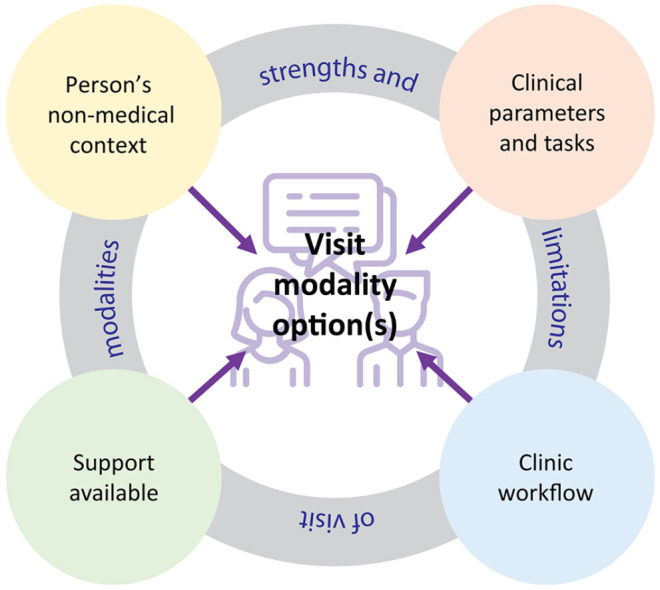

In addition to the general strengths and limitations of the visit modalities, when asked about factors to determine the choice of visit types, key considerations from the responses were categorized into four main themes: (1) the person’s nonmedical context, (2) support available, (3) clinical parameters and tasks, and (4) clinic workflow (Figure 1). Table 4 outlines individual key considerations and representative quotes, aligned with reference to specific dimensions of quality as defined by the BC Health Quality Matrix. 16

Figure 1.

Concept diagram for key considerations when selecting among available kidney care clinic (KCC) visit modalities.

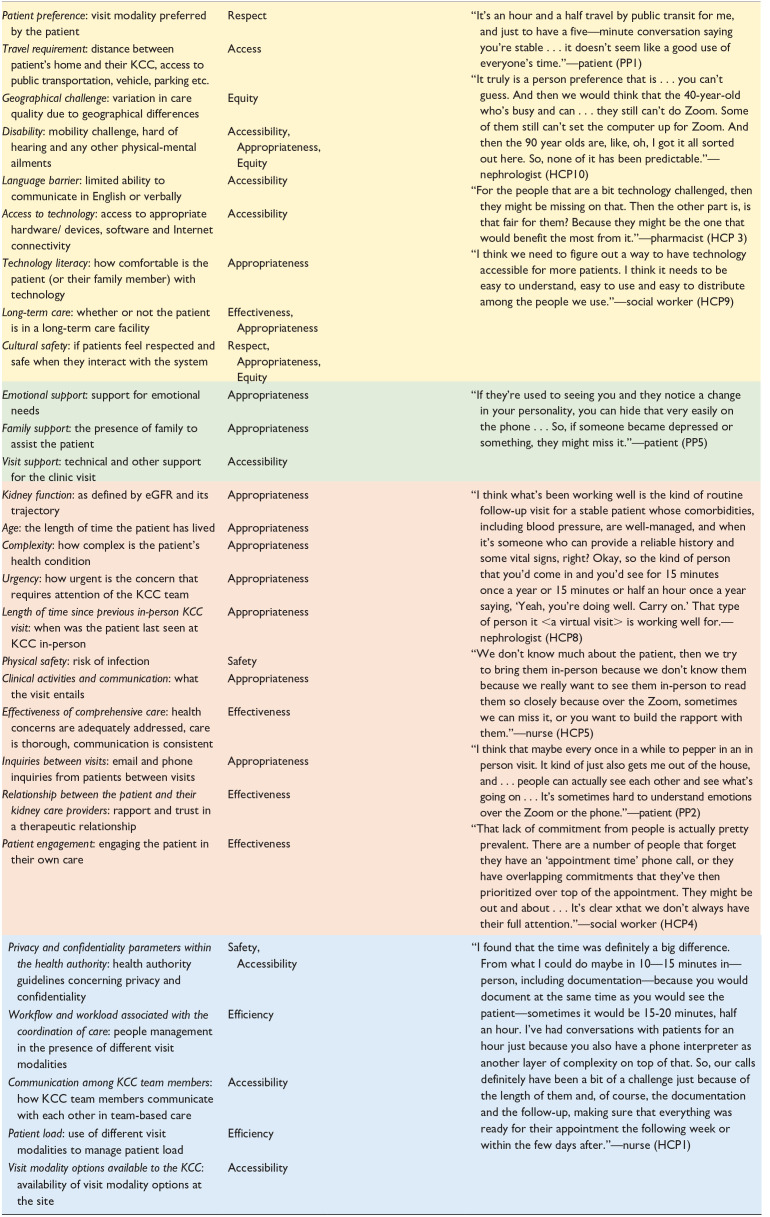

Table 4.

Key Considerations for Selection of Visit Modalities and Alignment With Dimensions of Quality Care Delivery.

| Key considerations | Quality care dimension a | Patient & family | Health care provider | Selected quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

Note. Dots in the columns indicate the participant group(s) in which each consideration was mentioned. Subgroups of key considerations are color-coded by the main themes and correspond to the color schemes in Figure 1: yellow for the person’s nonmedical context, green for support available, orange for clinical parameters and tasks and blue for clinical operations. Numbers in parentheses indicate participants. PP = patient participant; HCP = health care provider; KCC = kidney care clinic; BC = British Columbia.

Dimension of quality per the BC Health Quality Matrix. 17

General Strengths and Limitations of Visit Modalities

Both patient and health care provider participants reported similar strengths and limitations of the available visit modalities. Reported strengths of in-person visits included the ability to perform examinations, but also having a full view of each other which allows for inclusion of body language and nonverbal cues which were reported as being important to understanding each other. The main limitation reported for in-person visits was the need for travel with both the time and cost this entails. Both phone and video visits had the key strength of being faster and more convenient as participants could attend the visit from anywhere. Key limitations were the need to access technology especially for video visits, and while both phone and video visits were reported as potentially prone to distraction, with the inability to see each other and the fact that some providers reported that phone calls were taken when the patient was doing something else at the same time, distraction was reported more often as a limitation in reference to phone visits.

Person’s Nonmedical Context

Patient preference arose as the main consideration, as well as practical considerations of travel, geographical challenges and Internet connectivity. Convenience was cited as an important factor for why patients opt for VC, but on the other hand, some health care providers worried that this same convenience factor may make it more challenging to bring patients back for in-person visits when required needed. Preference for different visit modalities varied among patients and is individual rather than predictable across different groups of patients and these preferences may evolve over time.

The presence of any relevant disabilities, language barriers and the cultural appropriateness/safety of different visit types emerged also as considerations in this theme.

Support Available

Feedback in this category included themes of visit/technical support, but also emotional support. Specifically, patients may require emotional support that may be better offered in one visit modality versus another. The presence of family support may influence which visit modalities may work better for a visit; this is also individualized as in some situations involving these support people is easier in-person and in others it is more feasible virtually.

Health care providers also noted that with home-based videoconferencing, providing technical support or troubleshooting can sometimes use valuable time that would otherwise be spent providing care.

Clinical Parameters and Tasks

There was general agreement that the more medically complicated or urgent a situation was, the more likely an in-person visit would be preferable. Many of the patient, family caregiver and kidney health professional participants also mentioned the importance of body language for more serious conversation about treatment options or advance care planning and suggested that initiating those conversations may be more effective in-person.

Even if not required for a specific clinical task, most participants alluded to need for at least periodic in-person visits. Specifically, most health care providers suggested having an in-person visit at least once a year for each patient, with some suggesting greater frequency for patients with greater needs.

Physical safety such as COVID-19 prevalence rates at any given time, level of patient engagement, and patient ability to perform self-monitoring such as weight, fluid status and blood pressure also arose as key considerations.

Clinic Workflow

Health care providers identified several important clinical operation considerations when considering different visit types including which visit types were supported by local IT infrastructure, local privacy/confidentially rules, workflows and patient flows during a clinic session, patient loads, and ability to communicate/discuss patients with other KCC team members.

Both patient and health care provider participants also highlighted that virtual visits are changing the way clinicians practice and communicate with patients. There were suggestions for further professional training may be required beyond the use of hardware and software for virtual visits such as training in effective virtual communication.

Discussion

By exploring multiple domains of quality care delivery from both patient and health care provider perspectives, this evaluation has uncovered some key considerations regarding the use of VC in multidisciplinary CKD care. In terms of the practicalities of implementation, there was the expected finding of increased convenience and reduced travel with VC compared to in-person care. That said, convenience was balanced by feedback indicating difficulties of some patients and health care providers to interact in a virtual format. It should also be noted that although there are assumptions as to which patients may prefer certain visit modalities such as rural patients preferring to connect virtually rather than commute and older patients being averse to virtual tools, some patients have preferences opposite these assumptions and therefore these preferences must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, these situations may change over time, so this is not a one-time decision, but rather an iterative process that care teams engage with their patients in over time.

Beyond the practicalities and user-experiences with in-person and VC, the usage of an established framework for quality of care delivery combined with the thematic approach utilized enabled the reported considerations for visit type selection to be grouped into 4 themes: the person’s non-medical context, support available, clinical parameters and tasks, and clinic workflows. Being a new part of the KCC workflow, there is the potential for the visit type selection process to be time consuming and add to workload so in this way, distilling the many diverse factors into a more manageable list of key considerations may help KCC staff perform this task more easily and efficiently.

A key finding echoed by many patient and care provider participants is that integrating virtual visits may have less of an impact in situations where there is an established care relationship, but that VC is not conducive to building new trusting patient-care team relationships. These results are similar to those found in an evaluation of telephone CKD care 19 where respondents also reported difficulty establishing rapport, especially with new patient-provider relationships. A strong therapeutic relationship being foundational in multidisciplinary chronic care,1,2,4 this feedback may for example suggest a model of care wherein health care providers meet and interact with patients in person first to develop that rapport before integrating VC into their care. Similarly, both patient and health care providers indicated that for more complex care activities, in-person care was preferred to VC. Taken together, this feedback helps to inform visit selection but also suggests that when training health care providers in use of VC, in addition to the practical usage of virtual tools, it is important to provide specific guidance on effectively communicating, building relationships, and delivering care in a virtual environment.

The health care provider feedback also underscores the importance of clinic workflow when switching between virtual and in-person visits within a single clinic session. With a hybrid clinic model, KCC staff reported that a similar volume of tasks can be accomplished, but simultaneous scheduling of different visit modalities was reported as challenging. These findings resonate with a recent review in which the authors discussed the workload, barriers and challenges associated with VC modalities in managing chronic diseases in the primary care setting as “preconditions” that need to be addressed in order to achieve high quality VC. 20 As usage of virtual tools continues, further work will be needed from the operational perspective to determine how to best integrate different visit modalities in a manner that is conducive to effective and efficient clinic operations.

Finally, but perhaps most importantly, when using different visit modalities, the individual context of both patients and health care providers is important and this evaluation provides a list of considerations to assess in that regard. There are practical items such as availability of virtual tools and Internet connectivity for example, but our results indicate that in addition to these general considerations, individual health care providers and patients may be more or less able to effectively engage, communicate and interact in a virtual setting, and these individual differences should be taken into account. It is worth noting that for example patients who have challenges accessing and utilizing virtual tools may also be more likely to have other challenges accessing care, and in this way, it will be crucial to ensure that integration of VC does not have the unintended consequence of worsening existing inequities.

The strengths of this qualitative study include representation of participants across a large geographically and culturally diverse province, with patients and health care providers from an array of large and small, urban, and remote settings. In addition, the usage of an established framework for evaluating defined dimensions of quality care delivery allowed for identification of the diverse considerations outlined above.

The study is limited by the perspectives from a small group of participants, but this limitation was tempered by ensuring participation from each region and usage of the thematic saturation methodology. Regardless, there remains the potential for respondent bias; of note all health care provider participants and a large majority of the patient participants identified as women. Another important limitation is the potential for missing perspectives of marginalized patients, specifically those who may have difficulty interacting virtually and could also potentially be most disadvantaged by the implementation of VC. These voices are always perspectives are already difficult to elicit, and the fact that the interviews were only offered virtually due to pandemic restrictions at the time may have further contributed to this underrepresentation. For these reasons, these considerations will require specific evaluation in these potentially disadvantaged populations.

In conclusion, this evaluation has identified a list of key considerations, aligned with quality care delivery for health care providers and programs to consider as they determine how best to use different visit modalities in different patient and clinical situations. To enable person-centered kidney care, these results suggest that analyzing these considerations when deciding among visit modality options is an individualized, and importantly ongoing process involving the patient and their preferences. Further work in this area will be needed to validate these findings in a larger and more diverse group of patients and health care providers to determine optimal way(s) to integrate, implement and evaluate clinical outcomes with the combination of virtual and traditional modes of care delivery.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjk-10.1177_20543581231217833 for Patient and Clinician Experiences With the Combination of Virtual and In-Person Chronic Kidney Disease Care Since the COVID-19 Pandemic by Micheli Bevilacqua, Yuriy Melnyk, Helen Chiu, Janet Williams, Paul Watson, Brenda Lee, Palvir Dhariwal, Marlee McGuire, Julie Wei, Robin Chohan, Anne Logie, Michele Fryer, Dominik Stoll and Adeera Levin in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the BCR and PHSA Office of Virtual Health leadership, BCR methodology and CKD research groups for their guidance of this work as well as all members of the included working groups for their contributions to understanding VC in BC. The authors especially acknowledge all patients, health care providers, and administrators across BC who provided their valuable time and feedback during this evaluation process.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: The evaluation study protocol was reviewed by our institutional research ethics board and approved to proceed as a limited risk study exempt from full review. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and care providers who volunteered to participate in the interviews.

Consent for Publication: All authors provided consent for publication of this manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data or materials related to this manuscript are available upon request to the corresponding author, pending any privacy or confidentiality considerations.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Micheli Bevilacqua  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8321-7413

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8321-7413

Marlee McGuire  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9832-1854

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9832-1854

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Johns TS, Yee J, Smith-Jules T, Campbell RC, Bauer C. Interdisciplinary care clinics in chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levin A, Stevens P, Bilous RW, et al. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150. [Google Scholar]

- 3. White CA, Kappel JE, Levin A, et al. Management of Advanced chronic kidney disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: suggestions from the Canadian Society of Nephrology COVID-19 rapid response team. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120939354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. BC Renal. Best practices: kidney care clinics. www.bcrenalagency.ca. Published 2019. Accessed November 25, 2023.

- 5. Tan J, Mehrotra A, Nadkarni GN, et al. Telenephrology: providing healthcare to remotely located patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(3):200-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ishani A, Christopher J, Palmer D, et al. Telehealth by an interprofessional team in patients with CKD: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(1):41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crowley ST, Belcher J, Choudhury D, et al. Targeting access to kidney care via telehealth: the VA experience. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(1):22-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Narva AS, Romancito G, Faber T, Steele ME, Kempner KM. Managing CKD by telemedicine: the Zuni Telenephrology Clinic. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(1):6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lambooy S, Krishnasamy R, Pollock A, Hilder G, Gray NA. Telemedicine for outpatient care of kidney transplant and CKD patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(5):1265-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young A, Orchanian-Cheff A, Chan CT, Wald R, Ong SW. Video-based telemedicine for kidney disease care: a scoping review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(12):1813-1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lunney M, Thomas C, Rabi D, Bello AK, Tonelli M. Video visits using the zoom for healthcare platform for people receiving maintenance hemodialysis and nephrologists: a feasibility study in Alberta, Canada. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:20543581211008698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zuniga C, Riquelme C, Muller H, Vergara G, Astorga C, Espinoza M. Using telenephrology to improve access to nephrologist and global kidney management of CKD primary care patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(6):920-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. BC Renal. Guidance for kidney care clinics: service levels during a restart phase(s) of the COVID-19 pandemic. www.bcrenal.ca. Published 2020. Accessed November 25, 2023.

- 14. Bevilacqua M, Chiu H, Melnyk Y, et al. Protocol for a multistage mixed-methods evaluation of multidisciplinary chronic kidney disease care quality following integration of virtual and in-person care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022;9:20543581221103103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. BC Renal. Guide for project planning and evaluation. www.bcrenal.ca. Published 2021. Accessed November 25, 2023.

- 16. BC Patient Safety & Quality Council. BC health quality matrix. https://bcpsqc.ca/matrix. Published 2020. Accessed November 25, 2023.

- 17. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heyck Lee S, Ramondino S, Gallo K, Moist LM. A quantitative and qualitative study on patient and physician perceptions of nephrology telephone consultation during COVID-19. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022;9:20543581211066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stachteas P, Stachteas C, Symvoulakis EK, Smyrnakis E. The role of telemedicine in the management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maedica. 2022;17(4):931-938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjk-10.1177_20543581231217833 for Patient and Clinician Experiences With the Combination of Virtual and In-Person Chronic Kidney Disease Care Since the COVID-19 Pandemic by Micheli Bevilacqua, Yuriy Melnyk, Helen Chiu, Janet Williams, Paul Watson, Brenda Lee, Palvir Dhariwal, Marlee McGuire, Julie Wei, Robin Chohan, Anne Logie, Michele Fryer, Dominik Stoll and Adeera Levin in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease