Abstract

Objective

We explored various prognostic factors of motor outcomes in corticosteroid‐naive boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD).

Methods

The associations between parent‐reported neurodevelopmental concerns (speech delay, speech and language difficulties (SLD), and learning difficulties), DMD mutation location, and motor outcomes (6‐minute walk distance (6MWD), North Star Ambulatory Assessment (NSAA) total score, 10‐meter walk/run velocity, and rise from floor velocity) were studied in 196 corticosteroid‐naive boys from ages 4 to less than 8 years.

Results

Participants with SLD walked 25.8 fewer meters in 6 minutes than those without SLD (p = 0.005) but did not demonstrate statistical differences in NSAA total score, 10‐meter walk/run velocity, and rise from floor velocity. Participants with distal DMD mutations with learning difficulties walked 51.8 fewer meters in 6 minutes than those without learning difficulties (p = 0.0007). Participants with distal DMD mutations were slower on 10‐meter walk/run velocity, and rise from floor velocity (p = 0.02) than those with proximal DMD mutations. Participants with distal DMD mutations, who reported speech delay or learning difficulties, were slower on rise from floor velocity (p = 0.04, p = 0.01) than those with proximal DMD mutations. The mean NSAA total score was lower in participants with learning difficulties than in those without (p = 0.004).

Interpretation

Corticosteroid‐naive boys with DMD with distal DMD mutations may perform worse on some timed function tests, and that those with learning difficulties may perform worse on the NSAA. Pending confirmatory studies, our data underscore the importance of considering co‐existing neurodevelopmental symptoms on motor outcome measures.

Introduction

Dystrophin—the protein product of the dystrophin gene (DMD)—plays vital roles as a membrane scaffold and stabilizer in skeletal and cardiac muscles, and in synaptogenesis and cell signaling pathways in the brain. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Mutations in DMD cause Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), an X‐linked multi‐system disease characterized by progressive skeletal muscle wasting and weakness, diaphragmatic weakness, heart failure, neurodevelopmental co‐morbidities, and cognitive impairments. 6 In the brain, full‐length and shorter dystrophin isoforms are transcribed from unique exons. Distal DMD mutations including nucleotides 3’ DMD as well as DMD intron 44 have been shown to affect the expression of shorter dystrophin isoforms (Dp140, Dp116, and Dp71). 7

In recent years, there has been greater appreciation of the neurodevelopmental symptoms in DMD. Rates of autism spectrum and attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorders are 3 to 4 times higher in DMD than in the general population 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ; these symptoms affect infant‐parent bonding, schooling, and social relationships. 16 Nearly 100% of boys with DMD have impairment in cognitive flexibility, big‐picture thinking and planning, collectively called executive function, 7 which contribute to nearly 50% of developmental gains in intellectual function during childhood. 17 Not surprisingly, parents report that these cumulative neurodevelopmental symptoms interfere with schooling, peer relationships, and development of self‐efficacy skills. 16 Further, we and others have shown that speech delay is more common in DMD than in the general population. 13 , 14 , 19 Our prior work from Finding the Optimal Regimen for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (FOR‐DMD) study showed that 38% of the enrolled boys reported speech delay, and this symptom was more common in boys with distal DMD mutations compared to those with proximal DMD mutations. 19

Co‐existing neurodevelopmental symptoms in DMD appear to be associated with worse long‐term motor, respiratory, and cardiac outcomes. A retrospective study analyzed data from 75 corticosteroid‐naive boys with DMD followed longitudinally over a 10‐year period from a single national neuromuscular referral hospital. 18 A subgroup of boys (n = 15) whose initial presenting symptom of DMD was “psychomotor delay” walked independently later (mean 20 months, SD 7.9 months) and lost ambulation earlier (mean 9 years, SD 1.6 years) than the subgroup of boys who presented with “pure motor delay” (n = 16); the latter group walked independently at a mean of 15 months (SD 3.8 months) and lost ambulation at a mean of 12.6 years (SD 2 years). Likewise, both cardiac and respiratory declines occurred earlier in the subgroup presenting with “psychomotor delay.” Five of the 15 boys in this subgroup had a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 55% prior to 10 years of age, compared to none of the boys in the “pure motor delay” subgroup. In addition, mean forced vital capacity was 65% at 10 years of age in the subgroup presenting with “psychomotor delay,” compared to 80% at 10 years of age in the subgroup presenting with “pure motor delay.”

In this study, we explored whether neurodevelopmental concerns—namely speech and language delay (SLD), speech delay, and learning difficulties—are prognostic of pretreatment motor function in DMD. We postulated that young corticosteroid‐naive boys with neurodevelopmental concerns or with distal DMD mutations would demonstrate worse performance on motor function tests than those without neurodevelopmental concerns or with proximal DMD mutations.

Methods

Study design and participants

The FOR‐DMD trial enrolled 196 corticosteroid‐naive boys between the ages of 4 and <8 years in five countries with the aim of comparing three different corticosteroid regimens with respect to efficacy and safety. Detailed information on the rationale and study design has been previously published. 20 Briefly, the inclusion criteria for the FOR‐DMD trial were as follows: corticosteroid‐naive boys with genetically‐confirmed DMD mutation, ages 4 years to less than 8 years, able to arise independently from floor and able to provide reproducible forced vital capacity (FVC) measurements, as well as parent or guardian able to give written consent and comply with study visits and drug administration plan. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) and the Principles of Good Clinical Practice. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents/legal guardians of the study participants prior to commencement of study procedures. This clinical trial is registered under ClinicalTrials.Gov (NCT01603407).

Study measures

In this study, neurodevelopmental concerns were defined broadly. We extracted parent‐reported concerns of SLD and the age at which the child first spoke in full sentences (language acquisition) from the medical history form completed at the screening visit. SLD was queried as present, absent, or unknown. Speech delay was defined to be present if the parent had reported that the age of first speaking in full sentences was later than 42 months. 21 Learning difficulties were reported as present, absent, or unknown by parent. Motor function outcomes obtained at the baseline visit (or screening visit if the value at the baseline visit was missing) included six‐minute walk distance (6MWD), North Star Ambulatory Assessment (NSAA) total score, 10‐meter walk/run velocity, and rise from floor velocity. All of these tests were administered and recorded by a trained study‐team physical therapist.

DMD mutation data

DMD mutation data were available for 193 of 196 participants who were categorized as having proximal DMD (proximal to 5’ DMD intron 44) or distal DMD (mutations in 3’ DMD including intron 44) mutations.

Statistical analysis

For each of the motor function outcomes, three analyses of covariance models were fit, one that included SLD, a second that included speech delay, and a third that included learning difficulties; all models included DMD mutation and age. These models were used to estimate differences in adjusted mean outcome between boys with distal versus proximal DMD mutations, between boys with and without SLD, between boys with and without speech delay, and between boys with and without learning difficulties. The interactions between DMD mutation type and either SLD, speech delay, or learning difficulties were examined by adding the respective interaction term to the appropriate model. Because the models with SLD included larger sample sizes than the models with speech delay and learning difficulties, the results concerning differences between those with distal versus proximal DMD mutations are interpreted using the former model. Due to the exploratory nature of the analyses, no corrections were performed for multiple comparisons unless an interaction was identified, in which case subgroup comparisons incorporated a Tukey–Kramer adjustment.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 196 participants were enrolled in the FOR‐DMD trial. The mean age at time of baseline motor function assessment was 5.8 years (SD 1.0) were enrolled in the FOR‐DMD study. Parent‐reported SLD was reported in 75 of 195 participants (38%; data missing in 1 participant), and speech delay was reported in 18 of 167 participants (11%; data missing in 29 participants). In the 167 participants with available data on speech and language acquisition, speech delay was reported in 16 of the 67 participants with SLD, and SLD was reported in 16 of the 18 with speech delay. Learning difficulties were reported in 50 of 181 boys (28%). Among the 48 participants for whom the severity of learning difficulties was reported, the severity was mild in 69% (33/48), moderate in 29% (14/48), and severe in 2% (1/48). The mean age of participants with and without SLD, and with and without speech delay was the same (5.8 years). The mean ages of participants with and without learning difficulties were 6.2 and 5.8 years, respectively. The numbers of participants with proximal DMD versus distal DMD mutations were 88 and 105, respectively. The mean ages of participants with proximal versus distal DMD mutations were 5.9 and 5.8 years, respectively.

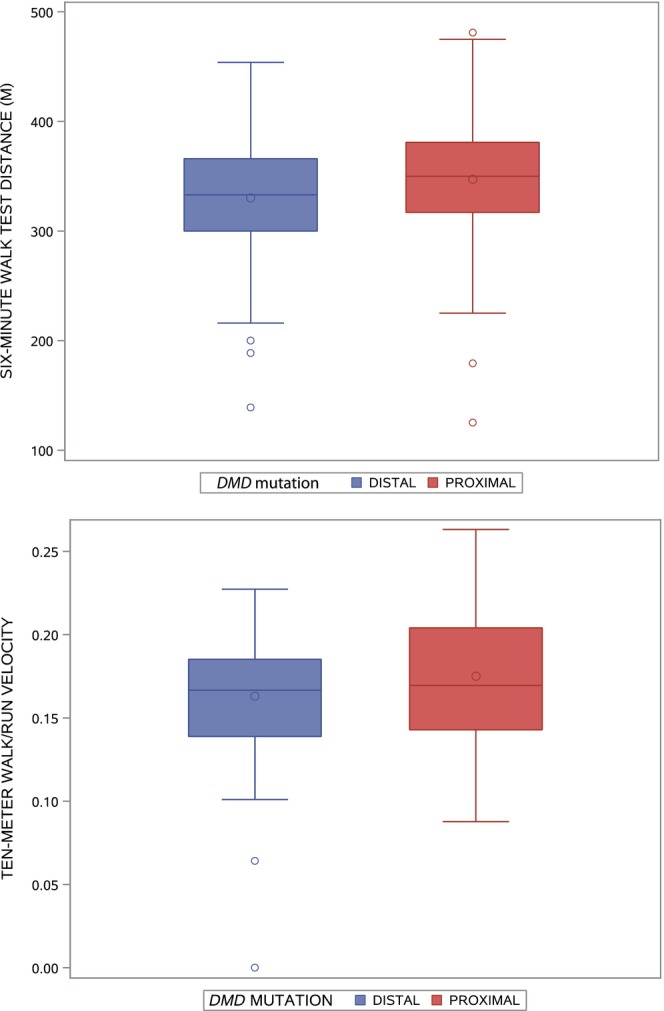

6MWD

Results of the analysis of covariance models for 6MWD are presented in Table 1. Those with SLD had an adjusted mean 6MWD of 319.4 m compared to 345.2 m in those without SLD (group difference = −25.8 m, 95% confidence interval [CI] ‐43.7 to −7.8, p = 0.005). This difference was consistent between those with distal (−25.1 m) and proximal (−26.8 m) DMD mutations (p = 0.93 for the interaction between SLD and DMD mutation type). The difference in adjusted mean 6MWD between those with distal versus proximal DMD mutations was −13.4 m (95% CI −30.9 to 4.2, p = 0.13; Fig. 1, left). The difference in adjusted mean 6MWD between those with and without speech delay was −16.6 m (95% CI −47.6 to 14.5, p = 0.29). In the model with learning difficulties, there was an interaction between learning difficulties and DMD mutation type (p = 0.03), with the adjusted mean 6MWD being lower in those with distal DMD mutations and learning difficulties (291 m) than in those in the other three groups (adjusted mean 6MWD ranging from 49.3 to 56.1; Table 1, Fig. 1, right).

Table 1.

Associations between 6‐minute walk distance and DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, speech delay, and learning difficulties.

| (a) Model with DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 6MWD (m) | Mean 6MWD (m) | ||||||

| DMD Mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech and language difficulties | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 325.6 | 339.0 | −13.4 (−30.9, 4.2) | 0.13 | 319.4 | 345.2 | −25.8 (−43.7, −7.8) | 0.005 |

| (b) Model with DMD mutation, speech delay, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 6MWD (m) | Mean 6MWD (m) | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech delay 1 | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 317.7 | 336.4 | −18.7 (−38.4, 1.0) | 0.06 | 318.8 | 335.3 | −16.6 (−47.6, 14.5) | 0.29 |

| (c) Model with DMD mutation, learning difficulties, interaction between DMD mutation and learning difficulties, and age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group (DMD mutation/learning difficulties) | ||||

| Distal/yes | Proximal/yes | Distal/no | Proximal/no | |

| Mean 6MWD (m) | 290.6 | 339.9 | 342.4 | 346.7 |

| Difference vs. distal/yes group | 49.3 | 51.8 | 56.1 | |

| 95% CI for difference 2 | (1.6, 96.9) | (17.6, 86.0) | (22.8, 89.4) | |

| p‐value 2 | 0.04 | 0.0007 | 0.0001 | |

6MWD, six‐minute walk distance; CI, confidence interval.

Speech delay was defined as age first speaking in full sentences >42 months.

Adjusted for all six possible pairwise group comparisons using the Tukey–Kramer method; differences among the proximal/yes, distal/no, and proximal/no groups were not statistically significant (p > 0.97).

Figure 1.

Boxplots of 6‐minute walk distance in meters by DMD mutation (proximal, distal) (left), and interaction between DMD mutation and learning difficulties (right). The line inside the box represents the median, and the circle inside the box represents the mean. The ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution; the lines extending from the boxes indicate the range of the data, with the exception of outlier values (indicated by circles) that are more than (1.5 × interquartile range) from the nearest quartile.

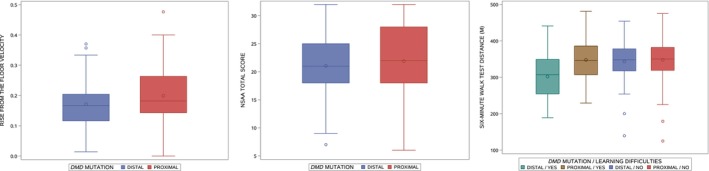

Ten‐meter walk/run velocity

Results of the analysis of covariance models for 10‐meter walk/run velocity are presented in Table 2. Differences in adjusted mean 10‐meter walk/run velocity between those with (1.72 m/sec) and without (1.67 m/sec) SLD (p = 0.34), and between those with (1.72 m/sec) and without (1.68 m/sec) speech delay (p = 0.68), were not significant. Those with a distal DMD mutation had an adjusted mean velocity of 1.63 m/sec compared to 1.76 m/sec in those with a proximal DMD mutation (group difference = −0.13 m/sec, 95% CI −0.24 to −0.02, p = 0.02; Fig. 2, left). This difference was slightly larger in those with SLD (−0.24 m/sec) than in those without SLD (−0.07 m/sec), but the interaction between the location of DMD mutation and SLD was not significant (p = 0.13). The difference in adjusted mean velocity between those with (1.60 m/sec) and without (1.72 m/sec) learning difficulties was −0.12 m/sec (95% CI −0.25 to 0.01, p = 0.07).

Table 2.

Associations between 10‐meter walk/run velocity and DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, speech delay, and learning difficulties.

| (a) Model with DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 10‐meter walk/run velocity (m/sec) | Mean 10‐meter walk/run velocity (m/sec) | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech and language difficulties | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 1.63 | 1.76 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.02) | 0.02 | 1.72 | 1.67 | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.17) | 0.34 |

| (b) Model with DMD mutation, speech delay, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 10‐meter walk/run velocity (m/sec) | Mean 10‐meter walk/run velocity (m/sec) | ||||||

| DMD Mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech delay 1 | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 1.64 | 1.76 | −0.12 (−0.24, 0.00) | 0.05 | 1.72 | 1.68 | 0.04 (−0.15, 0.23) | 0.68 |

| (c) Model with DMD mutation, learning difficulties, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 10‐meter walk/run velocity (m/sec) | Mean 10‐meter walk/run velocity (m/sec) | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Learning difficulties | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 1.61 | 1.71 | −0.11 (−0.22, 0.01) | 0.06 | 1.60 | 1.72 | −0.12 (−0.25, 0.01) | 0.07 |

CI, confidence interval.

Speech delay was defined as age first speaking in full sentences >42 months.

Figure 2.

Boxplots of motor outcomes by DMD mutation. Ten‐meter walk/run velocity (left), rise from the floor time (middle), and NSAA (right). The line inside the box represents the median, and the circle inside the box represents the mean. The ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution; the lines extending from the boxes indicate the range of the data, with the exception of outlier values (indicated by circles) that are more than (1.5 × interquartile range) from the nearest quartile.

Rise from the floor velocity

Results of the analysis of covariance models for rise from the floor velocity are presented in Table 3. Differences in adjusted mean rise from the floor velocity between those with (0.184 rise/sec) and without (0.187 rise/sec) SLD (p = 0.77), and between those with (0.161 rise/sec) and without (0.189 rise/sec) speech delay (p = 0.16), were not significant. Those with a distal DMD mutation had an adjusted mean velocity of 0.171 rise/sec compared to 0.199 rise/sec in those with a proximal DMD mutation (group difference = −0.028 rise/sec, 95% CI −0.052 to −0.005, p = 0.02; Fig. 2, center). This difference was slightly larger in those with SLD (−0.040 rise/sec) than in those without SLD (−0.022 rise/sec), but the interaction between DMD mutation type and SLD was not significant (p = 0.47). The difference in adjusted mean velocity between those with (0.169 m/sec) and without (0.189 m/sec) learning difficulties was −0.020 rise/sec (95% CI −0.047 to 0.006, p = 0.14).

Table 3.

Associations between rise from the floor velocity and DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, speech delay, and learning difficulties.

| (a) Model with DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rise from the floor velocity (rise/sec) | Mean rise from the floor velocity (rise/sec) | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech and language difficulties | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 0.171 | 0.199 | −0.028 (−0.052, −0.005) | 0.02 | 0.184 | 0.187 | −0.004 (−0.027, 0.020) | 0.77 |

| (b) Model with DMD mutation, speech delay, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rise from the floor velocity (rise/sec) | Mean rise from the floor velocity (rise/sec) | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech delay 1 | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 0.162 | 0.188 | −0.025 (−0.050, −0.001) | 0.04 | 0.161 | 0.189 | −0.028 (−0.067, 0.011) | 0.16 |

| (c) Model with DMD mutation, learning difficulties, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rise from the floor velocity (rise/sec) | Mean rise from the floor velocity (rise/sec) | ||||||

| DMD Mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Learning difficulties | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 0.164 | 0.194 | −0.030 (−0.054, −0.006) | 0.01 | 0.169 | 0.189 | −0.020 (−0.047, 0.006) | 0.14 |

CI, confidence interval.

Speech delay was defined as age first speaking in full sentences >42 months.

NSAA total score

Results of the analysis of covariance models for NSAA total score are presented in Table 4. No differences in adjusted mean scores were apparent between those with distal versus proximal DMD mutations (Fig. 2, right), between those with and without SLD, and between those with and without speech delay. The mean NSAA total score was lower in those with reported learning difficulties (19.5) than in those without learning difficulties (22.2) (group difference = −2.7, 95% CI −4.6 to −0.9, p = 0.004).

Table 4.

Associations between North Star Ambulatory Assessment total score and DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, speech delay, and learning difficulties.

| (a) Model with DMD mutation, speech and language difficulties, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean NSAA total score | Mean NSAA total score | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech and language difficulties | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 21.0 | 21.7 | −0.7 (−2.3, 0.9) | 0.39 | 21.1 | 21.6 | −0.5 (−2.2, 1.1) | 0.51 |

| (b) Model with DMD mutation, speech delay, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean NSAA total score | Mean NSAA total score | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Speech delay 1 | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 20.7 | 21.3 | −0.6 (−2.4, 1.1) | 0.48 | 20.6 | 21.3 | −0.7 (−3.5, 2.1) | 0.64 |

| (c) Model with DMD mutation, learning difficulties, and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean NSAA total score | Mean NSAA total score | ||||||

| DMD mutation | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | Learning difficulties | Group difference (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

| Distal | Proximal | Yes | No | ||||

| 20.6 | 21.0 | −0.4 (−2.0, 1.2) | 0.61 | 19.5 | 22.2 | −2.7 (−4.6, −0.9) | 0.004 |

CI, confidence interval; NSAA, North Star Ambulatory Assessment.

Speech delay was defined as age first speaking in full sentences >42 months.

Discussion

DMD is a disease caused by mutations in a single gene; yet, heterogeneity in clinical presentation, disease severity, and disease progression are well‐documented. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Further, genetic modifiers as well the beneficial effects of oral corticosteroids—the standard‐of‐care—in DMD 32 significantly alter the trajectory of disease course. Given the resource‐intense nature of clinical trials in DMD, and several Phase 2/3 clinical trials failing to demonstrate a treatment effect on the primary outcome measure, 33 better understanding of prognostic factors that contribute to disease heterogeneity can help not only clinical trial design but can inform patient care and management.

Our objective with this study was to explore prognostic factors of motor outcomes related to broadly‐defined neurodevelopmental concerns (SLD, speech delay, learning difficulties) as well as DMD genotype in corticosteroid‐naive boys with DMD. We found that those with SLD walked an average of 26 fewer meters in the 6MWD compared to those without SLD but there were no significant differences between those with and without SLD with respect to NSAA total score and timed motor function tests. With regard to DMD mutation location and motor outcomes, those with distal DMD mutations walked an average of 19 fewer meters in the 6MWD compared to those with proximal DMD mutations, and were slower in 10‐meter walk/run velocity and rise from the floor velocity, but did not demonstrate significant differences in NSAA total score compared to those with proximal DMD mutations. With respect to learning difficulties and functional outcomes, we observed that those with distal DMD mutations and learning difficulties walked an average of 49–56 fewer meters in the 6MWD than those with proximal DMD mutations or no learning difficulties. Also, those with learning difficulties had a lower mean NSAA total score than those without learning difficulties.

Our reported findings of associations between performance on timed function tests and DMD mutation location are congruent with published literature. Chesshyre et al. recently reported associations between DMD mutation location, NSAA scores, and intelligence quotient (IQ). 34 While their stratification based on DMD mutation location was different from ours, those with most distal DMD mutations showed worse performance compared to those with proximal DMD mutations. The mean NSAA total score and mean timed functional tests at age 5 were lowest in research participants with distal DMD mutations. Furthermore, NSAA scores were lower by a mean of 2 points in those with intellectual deficit (intelligence quotient two standard deviations below the mean) compared to those with no intellectual deficit. In our study, all participants were corticosteroid‐naive whereas nearly 90% of the cohort reported by Chesshyre et al. received oral corticosteroids.

What are the mechanisms that mediate the association between DMD mutation location and the effect of shorter dystrophin isoforms on functional test performance? A lack of task comprehension and attentional influence on functional tests have been reported. 35 , 36 While it is clear that “verbal encouragement” improves performance on the 6MWT, this evidence comes from a well‐designed study conducted on older adults. 37 In our current analysis and earlier publication from the FOR‐DMD trial, 19 we found only 8% of participants reporting attentional difficulties, though a formal diagnosis of ADHD is not always established prior to age 6. It is possible that mild attentional difficulties are undetected or under‐reported in this age range. Future clinical trials in DMD could consider additional nonmotor attention assessment to understand whether attentional difficulties confound motor assessment.

A neurodevelopmental symptom that has consistently been reported in DMD is SLD. Interestingly, the initial description by Duchenne de Boulogne described expressive language delay in boys with progressive skeletal muscle weakness. 38 More than 150 years later, the neurobiological underpinnings of SLD in DMD have not been investigated. SLD is an “encompassing” term and refers to both speech disorder (sound and word production) and language disorder (how words are used to communicate). We tried to discern whether the relationships between SLD and functional motor measures in our study were primarily driven by speech versus language disorder by using the age of language acquisition as an index of language disorder. We were not able to discern an association between 6MWD and the age of language acquisition, possibly because only 18 of the 167 participants with data on the timing of language acquisition had a reported speech delay.

While the strengths of our study include the large number of corticosteroid‐naive genetically defined participants with DMD and inclusion of age‐appropriate functional assessments, our study is not without limitations. The first limitation is that we did not perform objective SLD assessments in participants whose parents reported SLD or speech delay. Such objective assessment would provide greater distinction between speech versus language function abnormalities in DMD. Future studies of standardized SLD assessments would address this knowledge gap. The second limitation is that the p values arising from the statistical tests were not adjusted for multiple comparisons as our data analysis is exploratory, and these preliminary findings require confirmation in larger, independent cohorts.

Based on our study findings and precedent in literature, we recommend considering including brief cognitive assessments for future clinical trials in DMD such as the National Institutes of Health Toolbox Cognitive Battery, 39 digit span, 40 and standardized neurodevelopmental survey and SLP assessment. Many of these assessments can be conducted within 1 h without too much burden on clinical trial participants. These measured variables can be incorporated as potential covariates in final trial data analyses.

The current landscape of DMD, both from screening and therapeutic standpoint, are advancing rapidly. Although available antisense oligonucleotide therapy and emerging gene therapy are not restorative of CNS pathology in DMD, with anticipated newborn screening being planned for implementation, we forecast that targeting the brain in CNS is going to be the next therapeutic frontier. In sum, our data support more comprehensive neurodevelopmental assessment in DMD in order to better serve skeletal health.

Funding Information

This study was sponsored by The National Institutes of Health (study number U01NS061799) and has also received funding from Telethon Italy, Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), and Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD). We acknowledge the patient and family organizations including Action Duchenne, Muscular Dystrophy UK, Muscular Dystrophy Canada, and Benni&Co/Parent Project for their promotion of the study. The FOR DMD Steering Committee and the study site Investigators are members of the Muscle Study Group. Michela Guglieri and Kate Bushby are part of the Medical Research Council (UK) and TREAT NMD who also supported the study.

Conflict of Interest

Dr Guglieri reported receiving grants from Duchenne UK, the European Union's Horizon 2020 program for the Vision‐DMD study (in collaboration with ReveraGen BioPharma Inc), and Sarepta Therapeutics; serving as a consultant to Dyne Therapeutics Inc, Pfizer, and NS Pharma Inc; receiving personal fees from Sarepta Therapeutics; and receiving nonfinancial support from Italfarmaco, Pfizer, ReveraGen BioPharma Inc, and Santhera Pharmaceuticals. Dr McDermott reported receiving grant support from PTC Therapeutics and receiving personal fees from Fulcrum Therapeutics, NeuroDerm Ltd, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Catabasis Pharmaceuticals, Vaccinex Inc, Cynapsus Therapeutics, Neurocrine Biosciences, Voyager Therapeutics, Prilenia Therapeutics, ReveraGen BioPharma Inc, and NS Pharma Inc. Dr Thangarajh reported serving as a consultant to Sarepta Therapeutics and speaker for NS Pharma Inc. Dr Griggs reported serving as a consultant to Strongbridge and Stealth Pharmaceuticals; receiving personal fees from Solid Biosciences and Elsevier; serving as chair of the research advisory committee and is a board member of the American Brain Foundation; and serving on the executive committee of the Muscle Study Group, which receives support for its activities from pharmaceutical companies.

Author Contributions

M.T., M.M., M.G., R.G.: study concept and design; M.M.: data analysis including statistical evaluation and data interpretation; M.T. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers U01NS61795 and U01NS061799. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional financial support of the study was provided by Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc., PTC Therapeutics, Inc., Telethon Italy, Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), and Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD). The FOR‐DMD Steering Committee and the study site investigators are members of the Muscle Study Group. Mathula Thangarajh was supported by the American Academy of Neurology/American Brain Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship (2015 – 2017) and by the American Academy of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine Development Grant (2017 – 2019) and gratefully acknowledges the current support by VCU Wright Center for Clinical & Translation Research (CCTR) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) UM1TR004360 and K12TR004364 and R21TR004007.

FOR‐DMD investigators of the Muscle Study Group are listed below.

Kate Bushby, MD, John Walton Muscular Dystrophy Research Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne; Elaine McColl, PhD, John Walton Muscular Dystrophy Research Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne; Volker Straub, MD, PhD, Clinical Research Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne; Henriette van Ruiten, MD, Clinical Research Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne; Anna Mayhew, PT, Clinical Research Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne; Rabi Tawil, MD, University of Rochester, Rochester; Kimberly A. Hart, MA, University of Rochester, Rochester; Williams Martens, BA, University of Rochester, Rochester; Stephanie Gregory, University of Rochester, Rochester; Barbara E. Herr, MS, University of Rochester, Rochester; Mary W. Brown, MS, RN, University of Rochester, Rochester; Emma Ciafaloni, MD, University of Rochester, Rochester; Katy Eichinger, PhD, PT, University of Rochester, Rochester; Debra Guntrum, MS, FNP, University of Rochester, Rochester; Janbernd Kirschner, MD, Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Germany; Sabine Schneider‐Fuchs, PhD, Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Germany; Tracey Willis, PhD, Robert Jones & Agnes Hunt Orthopedic Hospital, Oswestry; Perry B. Shieh, MD, PhD, University of California, Los Angeles; Loretta Staudt, MS, PT, University of California, Los Angeles; Ummulwara Qasim, University of California, Los Angeles; Anne‐Marie Childs, MRCP, FRCPCH, Leeds Teaching Hospitals, Leeds; Lindsey Pallant, PT, Leeds Teaching Hospitals, Leeds; Neil Hall, Leeds Teaching Hospitals, Leeds; Asyah Chhibda, Leeds Teaching Hospitals, Leeds; Russell J. Butterfield, MD, PhD, University of Utah Medical Center, Salt Lake City; Melissa McIntyre, DPT, University of Utah Medical Center, Salt Lake City; Becky Crockett, University of Utah Medical Center, Salt Lake City; Iain Horrocks, MRCPCH, Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Yorkhill Hospital, Glasgow; Marina DiMarco, PT, Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Yorkhill Hospital, Glasgow; Jennifer Dunne, Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Yorkhill Hospital, Glasgow; Stefan Spinty, MRCPCH, MMedSc, Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool; Caroline Charlesworth, MRCPCH, Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool; Allison Shillington, PT, Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool; Lisa Hughes, Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool; Kevin M. Flanigan, MD, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus; Natalie F. Miller, DPT, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus; Allie Fenter, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus; Nancy L. Kuntz, MD, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital, Chicago; Colleen Blomgren, PT, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital, Chicago; Carolyn Hyson, PT, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital, Chicago; Theresa Oswald, MS, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital, Chicago; Giovanni Baranello, MD, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan; Lorenzo Maggi, MD, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan; Maria Teresa Arnoldi, PT, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan; Angela Campanella, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan; Helen Roper, MD, FRCPCH, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham; Zoya Alhaswani, MD, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham; Heather McMurchie, PT, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham; Alison Watson, Pediatric Research Nurse, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham; Leslie Morrison, MD, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; Guangbin Xia, MD, PhD, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; Kathy Dieruf, PT, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; MacKenzie Cox, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; Jean K. Mah, MD, MSc, University of Calgary, Calgary; Angela Chiu, PT, Alberta Children's Hospital, Calgary; Natalia Rincon, MSc, Alberta Children's Hospital, Calgary; Adnan Y. Manzur, FRCPCH, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London; Francesco Muntoni, MD, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London; Jordan Butler, PT, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London; Hinal Patel, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London; Craig M. McDonald, University of California, Sacramento; Erik Henricson, MS, University of California, Sacramento; Alina Nicorici, PT, University of California, Sacramento; Randev Sandhu, University of California, Sacramento; Erica Goude, University of California, Sacramento; Ulrike Schara, MD, PhD, University of Essen, Germany; Andrea Gangfuss, MD, University of Essen, Germany; Barbara Andres, PT, University of Essen, Germany; Baerbel Leiendecker, University of Essen, Germany; Corinna Seifert, University of Essen, Germany; Maja von der Hagen, MD, Children's Hospital, Technical University Dresden; Ilka Lehnert, PT, Children's Hospital, Technical University Dresden; Katja Uhlitzsch, Children's Hospital, Technical University Dresden; Sabine Stein, PT, Medical Center – University of Freiburg, Germany; Sabine Wider, Medical Center – University of Freiburg, Germany; Richard J. Barohn, MD, University of Kansas Medical Center; Jeffrey Statland, MD, University of Kansas Medical Center; Melanie Glenn, MD, University of Kansas Medical Center; Melissa Currence, PTA, University of Kansas Medical Center; Laura Herbelin, PT, University of Kansas Medical Center; Kiley Higgs, University of Kansas Medical Center; Craig Campbell, MD, University of Western Ontario, Ontario; Cheryl Scholtes, PT, Thames Valley Children's Centre, London; Rhiannon Hicks, Children's Hospital London Health Sciences Centre, Ontario; Jennifer Petzke, Children's Hospital London Health Sciences Centre, Ontario; Basil T. Darras, MD, Boston Children's Hospital; Amy Pasternak, PT, Boston Children's Hospital; Audrey Ellis, Boston Children's Hospital; Richard S. Finkel, MD, Nemours Children's Hospital, Orlando; Matt Civitello, PT, Nemours Children's Hospital, Orlando; Melisa Vega, Nemours Children's Hospital, Orlando; Hector Omar Oquendo, Nemours Children's Hospital, Orlando; Giuseppe Vita, MD, University of Messina & Nemo Sud Clinical Center AOU Policlinico Gaetano Martino, Messina; Gian Luca Vita, MD, Nemo Sud Clinical Center AOU Policlinico Gaetano Martino, Messina; Sonia Messina, MD, University of Messina & Nemo Sud Clinical Center AOU Policlinico Gaetano Martino, Messina; Imelda Hughes, MB, FRCPCH, Royal Manchester Children's Hospital; Fran Binici, Royal Manchester Children's Hospital; Tiziana Mongini, MD, AOU Citta della Salute e della Scienza, Turin; Enrica Rolle, PT, AOU Citta della Salute e della Scienza, Turin; Federica Ricci, AOU Citta della Salute e della Scienza, Turin; Elena Pegoraro, MD, PhD, University of Padova, Italy; Luca Bello, MD, PhD, University of Padova, Italy; Andrea Barp, MD, University of Milan, Italy; Claudio Semplicini, MD, PhD, University of Padova, Italy; Matthew P. Wicklund, MD, Hershey Penn State College of Medicine; Heidi Runk, Hershey Penn State College of Medicine; Ashutosh Kumar, MD, Hershey Penn State College of Medicine; Victoria Kern, MPT, Hershey Penn State College of Medicine; Ekkehard Wilichowski, MD, University Medical Center, Goettingen; Elke Hobbiebrunken, MD, Children's University Hospital, Goettingen; Gerda Roetmann, PT, Children's University Hospital, Goettingen; Anja Nolte, Children's University Hospital, Goettingen; W. Bryan Burnette, MD, Vanderbilt Children's Hospital, Nashville; Penny Powers, PT, Vanderbilt Children's Hospital, Nashville; Diana Davis, RN, BSN, Vanderbilt Children's Hospital, Nashville; James F. Howard, Jr, MD, University North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Jennifer Newman, PT, University North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Manisha Chopra, MBBS, CCRP, University North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Hugh J. McMillan, MD, MSc, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa; Catherine LaCroix, PT, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa; Rosa Ramos, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa; Taeun Chang, MD*, Children's National Medical Center, Washington, *Deceased; Brittney Drogo, PT, Children's National Medical Center, Washington; Juliana Lintner, Children's National Medical Center, Washington.

FOR‐DMD investigators of the Muscle Study Group are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Muscle Study Group; Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA); National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant R21TR004007; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health grants U01NS061799 and U01NS61795.; Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD) ; Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc., PTC Therapeutics, Inc.; VCU Wright Center for Clinical & Translation Research (CCTR) grants (CTSA) UM1TR004360 and K12TR004364.

Data Availability Statement

The FOR‐DMD study protocol has been previously published. 20 The FOR‐DMD clinical trial data will be deposited in a publicly available repository and will be released in late 2023.

References

- 1. Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, Mercuri E, Aartsma‐Rus A. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):13. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00248-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fritschy JM, Schweizer C, Brünig I, Lüscher B. Pre‐ and post‐synaptic mechanisms regulating the clustering of type a gamma‐aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAA receptors). Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31(Pt 4):889‐892. doi: 10.1042/bst0310889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fuentes‐Mera L, Rodríguez‐Muñoz R, González‐Ramírez R, et al. Characterization of a novel Dp71 dystrophin‐associated protein complex (DAPC) present in the nucleus of HeLa cells: members of the nuclear DAPC associate with the nuclear matrix. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(16):3023‐3035. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villarreal‐Silva M, Suárez‐Sánchez R, Rodríguez‐Muñoz R, Mornet D, Cisneros B. Dystrophin Dp71 is critical for stability of the DAPs in the nucleus of PC12 cells. Neurochem Res. 2010;35(3):366‐373. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0064-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Constantin B. Dystrophin complex functions as a scaffold for signalling proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838(2):635‐642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thangarajh M. The Dystrophinopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25(6):1619‐1639. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hinton VJ, De Vivo DC, Nereo NE, Goldstein E, Stern Y. Poor verbal working memory across intellectual level in boys with Duchenne dystrophy. Neurology. 2000;54(11):2127‐2132. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.11.2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu JY, Kuban KC, Allred E, Shapiro F, Darras BT. Association of Duchenne muscular dystrophy with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Neurol. 2005;20(10):790‐795. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200100201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ricotti V, Mandy WP, Scoto M, et al. Neurodevelopmental, emotional, and behavioural problems in Duchenne muscular dystrophy in relation to underlying dystrophin gene mutations. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(1):77‐84. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hendriksen JG, Vles JS. Neuropsychiatric disorders in males with duchenne muscular dystrophy: frequency rate of attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(5):477‐481. doi: 10.1177/0883073807309775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thangarajh M, Spurney CF, Gordish‐Dressman H, et al. Neurodevelopmental needs in young boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD): observations from the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group (CINRG) DMD Natural History Study (DNHS). PLoS Curr. 2018;10:ecurrents.md.4cdeb6970e54034db2bc3dfa54b4d987. doi: 10.1371/currents.md.4cdeb6970e54034db2bc3dfa54b4d987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caspers Conway K, Mathews KD, Paramsothy P, et al. Neurobehavioral concerns among males with Dystrophinopathy using population‐based surveillance data from the muscular dystrophy surveillance, tracking, and research network. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36(6):455‐463. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lundy CT, Doherty GM, Hicks EM. Should creatine kinase be checked in all boys presenting with speech delay? Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(7):647‐649. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.117028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cyrulnik SE, Fee RJ, De Vivo DC, Goldstein E, Hinton VJ. Delayed developmental language milestones in children with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. J Pediatr. 2007;150(5):474‐478. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soim A, Lamb M, Campbell K, et al. A Cross‐sectional study of school experiences of boys with Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Phys Disabil. 2016;35(2):1‐22. doi: 10.14434/pders.v35i2.21765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hendriksen JGM, Thangarajh M, Kan HE, Muntoni F. ENMC 249th workshop study group. 249th ENMC international workshop: the role of brain dystrophin in muscular dystrophy: implications for clinical care and translational research, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands, November 29th‐December 1st 2019. Neuromuscul Disord. 2020;30(9):782‐794. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2020.08.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fry AF, Hale S. Processing speed, working memory, and fluid intelligence: evidence for a developmental cascade. Psychol Sci. 1966;7(4):237‐241. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00366.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Desguerre I, Christov C, Mayer M, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD): definition of sub‐phenotypes and predictive criteria by long‐term follow‐up. PloS One. 2009;4(2):e4347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thangarajh M, Hendriksen J, McDermott MP, et al. Relationships between DMD mutations and neurodevelopment in dystrophinopathy. Neurology. 2019;93(17):e1597‐e1604. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guglieri M, Bushby K, McDermott MP, et al. Developing standardized corticosteroid treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;58:34‐39. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coplan J. Evaluation of the child with delayed speech or language. Pediatr Ann. 1985;14(3):203‐208. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19850301-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bello L, Kesari A, Gordish‐Dressman H, et al. Genetic modifiers of ambulation in the cooperative international neuromuscular research group Duchenne natural history study. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(4):684‐696. doi: 10.1002/ana.24370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bello L, D'Angelo G, Villa M, et al. Genetic modifiers of respiratory function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(5):786‐798. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pegoraro E, Hoffman EP, Piva L, et al. SPP1 genotype is a determinant of disease severity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2011;76(3):219‐226. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318207afeb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bello L, Morgenroth LP, Gordish‐Dressman H, et al. DMD genotypes and loss of ambulation in the CINRG Duchenne natural history study. Neurology. 2016;87(4):401‐409. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kelley EF, Cross TJ, Synder EM, et al. Influence of β2 adrenergic receptor genotype on risk of nocturnal ventilation in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):221. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1200-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bello L, Flanigan KM, Weiss RB, et al. Association study of exon variants in the NF‐κB and TGFβ pathways identifies CD40 as a modifier of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(5):1163‐1171. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hogarth MW, Houweling PJ, Thomas KC, et al. Evidence for ACTN3 as a genetic modifier of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14143. Published 2017 Jan 31. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spitali P, Zaharieva I, Bohringer S, et al. TCTEX1D1 is a genetic modifier of disease progression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28(6):815‐825. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0563-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weiss RB, Vieland VJ, Dunn DM, Kaminoh Y, Flanigan KM. United Dystrophinopathy project. Long‐range genomic regulators of THBS1 and LTBP4 modify disease severity in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(2):234‐245. doi: 10.1002/ana.25283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flanigan KM, Ceco E, Lamar KM, et al. LTBP4 genotype predicts age of ambulatory loss in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(4):481‐488. doi: 10.1002/ana.23819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Abresch RT, et al. Long‐term effects of glucocorticoids on function, quality of life, and survival in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2018;391(10119):451‐461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32160-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Markati T, De Waele L, Schara‐Schmidt U, Servais L. Lessons learned from discontinued clinical developments in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:735912. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.735912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chesshyre M, Ridout D, Hashimoto Y, et al. Investigating the role of dystrophin isoform deficiency in motor function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(2):1360‐1372. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoffman EP, McNally EM. Exon‐skipping therapy: a roadblock, detour, or bump in the road? Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(230):230fs14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shieh PB. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: clinical trials and emerging tribulations. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28(5):542‐546. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guyatt GH, Pugsley SO, Sullivan MJ, et al. Effect of encouragement on walking test performance. Thorax. 1984;39(11):818‐822. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.11.818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duchenne GBA. Recherches sur la paralysie musculaire pseudo‐hypertrophique ou paralysie myo‐sclérosique. Arch Gén Méd. 1868;11:5‐25. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thangarajh M, Kaat AJ, Bibat G, et al. The NIH toolbox for cognitive surveillance in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(9):1696‐1706. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50867 Erratum in: Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(12):2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thangarajh M, Elfring GL, Trifillis P, McIntosh J, Peltz SW. Ataluren phase 2b study group. The relationship between deficit in digit span and genotype in nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2018;91(13):e1215‐e1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The FOR‐DMD study protocol has been previously published. 20 The FOR‐DMD clinical trial data will be deposited in a publicly available repository and will be released in late 2023.