Abstract

Genetic characterization of the wb* gene in a series of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella strains possessing the mannose homopolymer as the O-specific polysaccharide was carried out. The partial nucleotide sequences and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis suggested that E. coli serotype O9a, a subtype of E. coli O9, might have been generated by the insertion of the Klebsiella O3 wb* gene into a certain E. coli strain.

O-antigen polysaccharide is the polysaccharide moiety of lipopolysaccharide, which is the major component of the outer membrane in gram-negative bacteria, and the O-specific polysaccharide is directed by the wb* gene cluster (previously referred to as rfb). Escherichia coli serotypes O8 and O9 have structurally the same O-specific mannose homopolysaccharide as Klebsiella serotypes O5 and O3, respectively (Table 1) (3, 9). It has been reported that there is no open reading frame between the wb* and his genes in E. coli O9 strain F719, suggesting the characteristic wc*-gnd-wb*-his gene organization (4, 5). In the wb* gene cluster, the region specific for each serotype seems to be flanked by two regions common to all four serotypes. One is the manC-manB region (12), and the other is the wbdC region (5, 12). Moreover, we have reported that all E. coli and Klebsiella strains possessing the mannose homopolymer may have the characteristic wc*-gnd-wb*-his gene organization (13). Thus, there might be a close evolutionary relationship among the wb* gene clusters in a series of strains possessing the O-specific mannose homopolymer. Recently, we have developed a monoclonal antibody that serologically discriminates E. coli O9a, a subtype of E. coli O9, from E. coli O9, and we found that a number of E. coli O9a strains had been classified as the E. coli O9 serotype (6). In fact, E. coli O9 and E. coli O9a are structurally and serologically similar to each other (Table 1). Further, an anti-E. coli O9a monoclonal antibody cross-reacts with Klebsiella O3 polysaccharides, suggesting the presence of E. coli O9a type O polysaccharides in Klebsiella O3 strains (6). It is of particular interest to clarify the evolutionary relationship between the E. coli O9a and O9 serotypes. In this study, we determined the nucleotide sequences of the wbdC, manC, manB, wzm, and wzt genes in a series of E. coli and Klebsiella strains possessing the O-specific mannose homopolymer, and we further analyzed the homology of the region between manB and wbdC with PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Here we describe the peculiar evolution of E. coli O9a.

TABLE 1.

Structure of the repeating units of O-specific mannose homopolysaccharide used in this study

| Serotype(s) | Structure of the O-antigen repeating unit |

|---|---|

| E. coli O8 and Klebsiella O5 | →3 Man 1 β→2 Man 1 α→2 Man 1 α→ |

| E. coli O9a | →3 Man 1 α→3 Man 1 α→2 Man 1 α→2 Man 1 α→ |

| E. coli O9 and Klebsiella O3 | →3 Man 1 α→3 Man 1 α→2 Man 1 α→2 Man 1 α→2 Man 1 α→ |

PCR amplification of the wb* gene cluster.

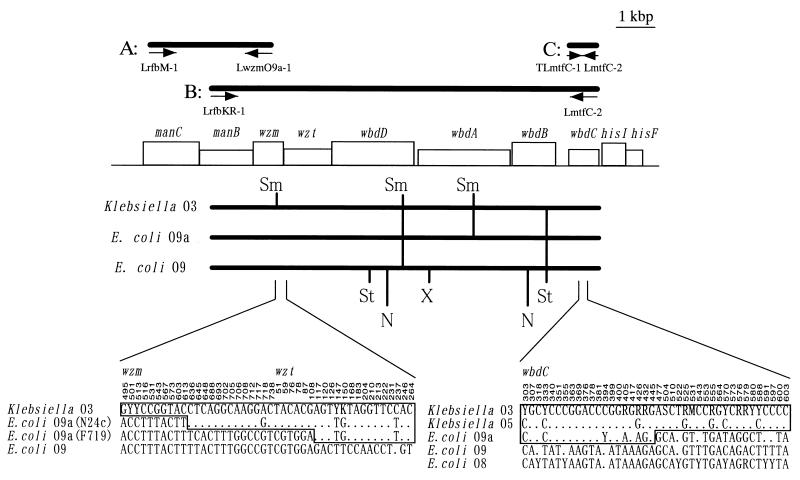

Bacterial strains used in this paper are listed in Table 2, footnote a. The O serotype of E. coli O9a strains was classified serologically with an anti-E. coli O9a monoclonal antibody (6). Bacterial cells were cultivated in L broth at 37°C with vigorous shaking. Chromosomal DNA was extracted as described by Jackson et al. (2). PCR amplification was carried out by using a mixture of 10 ng of chromosomal DNA or 2 μl of bacteria cultured overnight and subsequently heated at 98°C for 2 min as a template with 10 pmol of each oligonucleotide primer for wbdC and the manC-wzm region and with 20 pmol for the manB-wbdC region. The wbdC gene and the manC-wzm region were amplified with 30 cycles, each consisting of (i) a denaturation step of 20 s at 98°C and (ii) an annealing and a polymerization step of 5 min for the manC-wzm region and 2 min for the wbdC gene at 68°C. DNA polymerase, TaKaRa ex Taq, was purchased from Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. To amplify the manB-wbdC region, which is about 10 kbp, an LA PCR Kit, version 2, from Takara was used according to the procedure provided by the manufacturer. Oligonucleotide primers for amplification were designed on the basis of the DNA sequence of the E. coli F719 serotype O9a wb* (DDBJ accession no. D43637) as follows: for the manC-wzm region, LrfbM-1 (5′-TACCGGCAGTCGTCTCTGGCCGATGT-3′) and LwzmO9a-1 (5′-AGCCCCCAGGTTAACACCCCGGAAC-3′); for wbdC, TLmtfC-1 (5′-GCCGATGTTTTTACTTTTAGCCGGACA-3′) and LmtfC-2 (5′-GGTAGCAGCTCTCAGGATTTGCTTTCCAGC-3′); and for the manB-wbdC region, LrfbKR-1 (5′-GCTCTGGACTCAACGTTCAGACGCACCA-3′) and LmtfC-2 (5′-GGTAGCATCTCTCAGGATTTGCTTTCCAGC-3′). The locations of these primers around the wb* gene locus are shown in Fig. 1. The nomenclature for O-polysaccharide synthesis genes used in this paper follows the recent review of Reeves et al. (10).

TABLE 2.

Divergence in pairwise nucleotide sequence of wbdC within and between serotypes

| Serotypea | Divergenceb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within serotype | Among serotypes

|

||||

| E. coli O9 | E. coli O9a | Klebsiella O3 | Klebsiella O5 | ||

| E. coli O8 | 7.83 ± 3.87 (0.95 ± 0.47) | 7.25 ± 4.50 (0.88 ± 0.55) | 45.00 ± 3.16 (5.47 ± 0.38) | 70.17 ± 3.40 (8.54 ± 0.41) | 70.50 ± 2.07 (8.58 ± 0.25) |

| E. coli O9 | 0.00 (0.00) | 46.75 ± 0.46 (5.68 ± 0.06) | 71.17 ± 2.37 (8.66 ± 0.29) | 71.50 ± 0.58 (8.70 ± 0.07) | |

| E. coli O9a | 1.50 ± 0.55 (0.18 ± 0.07) | 35.25 ± 6.39 (4.29 ± 0.78) | 36.25 ± 4.83 (4.41 ± 0.59) | ||

| Klebsiella O3 | 15.33 ± 7.30 (1.87 ± 0.88) | 12.33 ± 7.71 (1.50 ± 0.94) | |||

| Klebsiella O5 | 18.00 (2.19) | ||||

Four strains of E. coli O8, two strains of E. coli O9, four strains of E. coli O9a, six strains of Klebsiella O3, and two strains of Klebsiella O5 were investigated. Strains (with serotypes given in parentheses were E. coli B1002 (O8:K?:H?), CO8 (O8:K?:H?), D282 (O8:K27−:H−), F492 (O8:K27−:H−), Bi316-42 (O9:K9:H12), H509d (O9:K57:H32), B993 (O9a:K−:H−), F379 (O9a:K29−:H−), F719 (O9a:K31−:H−), and N24c (O9a:K55:H−) and Klebsiella K-11 (O3:K11), K25SY (O3:K25−), K49S (O3:K49−), K51S1 (O3:K51−), K53 (O3:K53), Kasuya (O3:K1), K57M (O5:K57), and K61S (O5:K61−).

Expressed as mean number of different nucleotides ± standard deviation (mean percent difference ± standard deviation). All wbdC genes are 822 bp.

FIG. 1.

Genetic map and alignment sequences around the putative recombination sites. Fragments A, B, and C, produced by primers LrfbM-1 and LwzmO9a-1, TLmtfC-1 and LmtfC-2, and LrfbKR-1 and LmtfC-2, respectively, are shown above the genetic map of the E. coli F719 serotype O9a wb* gene cluster and 3′ end of the his operon. Restriction enzyme maps of the region from manB to wbdC in Klebsiella O3 and E. coli O9a and O9 are shown below the genetic map. Nucleotides at polymorphic sites around the putative recombination sites in the connective region of the wzm and wzt genes and in the middle of the wbdC gene are displayed at the bottom. Invariant sites are not shown. Restriction sites are based on the result of the PCR-RFLP. All nucleotide sequences except those of wzm and wzt in E. coli O9a are consensus sequences of all strains analyzed in each serotype indicated. The nucleotide numbers, relative to the 5′ end of each gene, are given above the sequences. Dots indicate bases identical to those in Klebsiella O3. The nucleotides in the regions similar to those in Klebsiella O3 are boxed. Abbreviations: N, NheI; Sm, SmaI; St, StuI; X, XbaI; K, G or T; M, A or C; R, A or G; S, C or G; Y, C or T.

In order to determine the nucleotide sequences of the manC-wzt region and the wbdC gene, the PCR products shown in Fig. 1 were sequenced directly by thermocycle sequencing reactions based on the dideoxy chain termination method (11), which were run in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA thermal cycler by a procedure recommended by Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif. Both strands were completely sequenced by use of PCR primers and additional internal oligonucleotides. The 3′ end of wbdC and its flanking region in E. coli H509d, Klebsiella sp. strain K25SY, and Klebsiella sp. strain K51S1 were sequenced as previously described (13), and the sequences of the region in other strains have been reported previously (13). A part of the sequence of the E. coli F492 serotype O8 wb* gene cluster, determined with plasmid pTSO8 subcloned from clone 31 (8, 14), was used in this study. Those nucleotide sequences were assembled, edited, and analyzed by using the SDC-GENETYX system (Software Development, Tokyo, Japan) and MEGA (7).

Nucleotide sequences of wbdC genes of E. coli O8, O9, and O9a and Klebsiella O3 and O5 serotype strains.

Based on the complete nucleotide sequences of wbdC genes from 17 strains in this study and E. coli F719 (5), the mean frequencies of the differences in nucleotide sequence within and between serotypes are shown in Table 2. The differences in wbdC nucleotide sequence between E. coli O8 and O9 and between Klebsiella O3 and O5 were very low (0.88 and 1.50%, respectively), and the values were almost the same as those within the same serotype strains (0 to 2.19%). On the other hand, the differences between E. coli (with the exception of O9a) and Klebsiella were higher than 8.5%. Incidentally, the differences between E. coli O9a and the other serotypes were 4.29 to 5.68% and showed intermediate values.

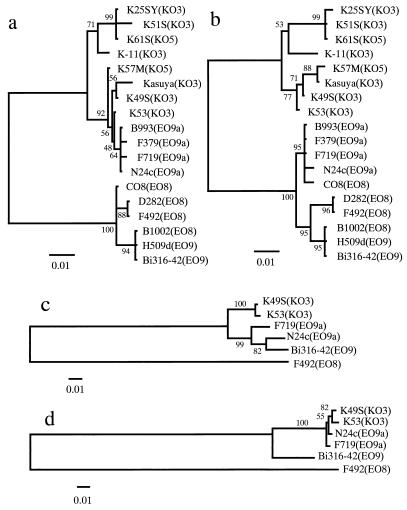

As shown in Fig. 1, the alignment analysis for the sequences of the wbdC genes of 18 strains demonstrated that the 5′ region of wbdC in E. coli O9a strains was very close to those of Klebsiella strains. In contrast, the 3′ region in E. coli O9a strains was very similar to those of other E. coli strains, compared with Klebsiella strains. Therefore, the wbdC gene in E. coli O9a was suggested to be a hybrid gene between wbdC of E. coli and wbdC of Klebsiella. Further, phylogenetic trees based on the neighbor-joining (NJ) method were constructed from the aligned sequences of the two regions (Fig. 2a and b). In the NJ tree constructed with the 5′ half of wbdC, a genetic cluster of E. coli O9a strains was classified on the same branch as Klebsiella strains (Fig. 2a). In the tree constructed with the 3′ half of wbdC, a genetic cluster of E. coli O9a strains was classified on the same branch as E. coli strains (Fig. 2b). Phylogenetic analysis also suggested that the 5′ half of wbdC in E. coli O9a was derived from Klebsiella and its 3′ half was derived from E. coli.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic trees constructed with the nucleotide sequences of the 5′ (bases 1 to 445) and 3′ (bases 477 to 822) halves of wbdC (a and b, respectively), wzm (c), and wzt (d). Branch lengths are proportional to evolutionary distances. Bootstrap values are given at the nodes. O serotypes are given in parentheses. Abbreviations: EO8, E. coli O8; EO9, E. coli O9; EO9a, E. coli O9a; KO3, Klebsiella O3; KO5, Klebsiella O5.

Nucleotide sequence of the manC-wzt region in E. coli O8, O9, and O9a and Klebsiella O3 strains.

Based on nucleotide sequence analysis of wbdC genes, the possibility was raised that the wb* gene of E. coli O9a, a subtype of the E. coli O9 serotype, might have evolved from the recombination of a certain wb* of Klebsiella O3 into an ancestral wbdC gene of an E. coli strain, but not directly from E. coli O9. Therefore, the nucleotide sequences of the region from the 56th nucleotide of manC to the 3′ end of wzt in E. coli F492 serotype O8, E. coli N24c and F719 serotype O9a, E. coli Bi316-42 serotype O9, and Klebsiella K49S and K53 serotype O3 were compared in order to examine the possibility of the insertion of the whole wb* of Klebsiella O3 into E. coli. Percent differences in nucleotide sequences of manC and manB among all strains tested were less than 8% (Table 3). manCB sequences were not necessarily classified into the O serotypes of E. coli and Klebsiella strains. Next, we compared the nucleotide sequences of wzm and wzt genes to examine the insertion of a shorter wb* region of Klebsiella O3 containing wbdC (Table 3). The differences of wzm and wzt genes between E. coli O8 and the other strains were higher than 35 and 43%, respectively, while those among E. coli O9, E. coli O9a, and Klebsiella O3 strains were less than 9% (Table 3). It is possible that wzm and wzt genes in E. coli O8 corresponded to the strain-specific region as described previously (12). The differences in wzm sequence between E. coli O9 and O9a strains were 2.9 and 3.6%, and those between E. coli O9a and Klebsiella O3 were 4.9 to 5.7% (Table 3). However, it should be noted that differences in the wzt nucleotide sequence between E. coli O9a and Klebsiella O3 were very small (no more than 1.5%), although those between E. coli O9 and O9a were approximately 8% (Table 3). Percent differences among wzt genes in E. coli O9, E. coli O9a, and Klebsiella O3 strains were almost consistent with those among the 5′ regions of their wbdC genes, suggesting that the wzt gene of E. coli O9a and the 5′ half of wbdC were transferred from a Klebsiella O3 strain at the same time. This idea was supported by the phylogenetic analysis, which showed that E. coli O9a and Klebsiella O3 were classified on the same branch in the wzt tree (Fig. 2d). Because of the difference in topology between the wzm and wzt trees (Fig. 2c and d), it was likely that the recombination event occurred around the connecting region between wzm and wzt. From the alignment analysis for the wzm-wzt region, two different potential recombination sites were found; one was at the 613th nucleotide of wzm and the other was at the 108th nucleotide of wzt (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Percent differences of nucleotide sequences of manC, manB, wzm, and wzt

| Serotype and strain | Gene | % Difference

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli O9, Bi316-42 |

E. coli O9a

|

Klebsiella O3

|

||||

| N24c | F719 | K49S | K53 | |||

| E. coli O8, F492 | manCa | 6.2 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 3.9 |

| manB | 4.4 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| wzm | 37.8 | 37.3 | 36.8 | 35.6 | 35.8 | |

| wzt | 43.8 | 45.0 | 44.9 | 45.1 | 45.1 | |

| E. coli O9, Bi316-42 | manC | 6.9 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.7 | |

| manB | 4.7 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | ||

| wzm | 2.9 | 3.6 | 7.7 | 7.9 | ||

| wzt | 8.2 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 8.2 | ||

| E. coli O9a | ||||||

| N24c | manC | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | ||

| manB | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.6 | |||

| wzm | 4.3 | 5.5 | 5.7 | |||

| wzt | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 | |||

| F719 | manC | 2.0 | 2.3 | |||

| manB | 1.5 | 1.7 | ||||

| wzm | 4.9 | 5.1 | ||||

| wzt | 1.2 | 1.5 | ||||

| Klebsiella O3, K49S | manC | 1.6 | ||||

| manB | 0.7 | |||||

| wzm | 0.5 | |||||

| wzt | 0.8 | |||||

Nucleotide sequences of manC were compared in the region from the 56th nucleotide to the 3′ end.

PCR-RFLP analysis of the manB-wbdC region from E. coli O9, E. coli O9a, and Klebsiella O3 serotype strains.

As described above, the insertion of the region from wzt to the 5′ half of wbdC of Klebsiella O3 into an ancestor of E. coli O9a strains was suggested. In order to study the homology of the region, the digestion patterns of the regions in the different serotypes were compared by PCR-RFLP. PCR-amplified fragments of the manB-wbdC region in E. coli Bi316-42 and H509d serotype O9, E. coli N24c and F379 serotype O9a, and Klebsiella K49S and K53 serotype O3 were digested by seven restriction enzymes, i.e., BamHI, NheI, SacI, SalI, SmaI, StuI, and XhoI, and their fragment lengths were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. When digested by BamHI, SacI, or SalI, all strains tested exhibited the same digest pattern upon electrophoresis. Digestion with the other enzymes, except for SmaI, caused the same electrophoretic pattern in E. coli O9a and Klebsiella O3 strains, as predicted from the nucleotide sequence of the wb* gene cluster of E. coli F719 serotype O9a, whereas it caused a different pattern in E. coli O9 strains (Fig. 1). Thus, PCR-RFLP analysis demonstrated that the region from wzt to the 5′ half of wbdC in E. coli O9a had higher homology to that in Klebsiella O3 than to that in E. coli O9. This finding strongly supported the hypothesis that the region from wzt to the 5′ half of wbdC in E. coli O9a is derived from Klebsiella O3, not from E. coli O9.

Conclusions.

In this study we have demonstrated that the nucleotide sequence of the region from wzt to the 5′ half of wbdC in E. coli O9a, which covers about two-thirds of the E. coli O9a wb* gene cluster, has a higher homology to that in Klebsiella O3 than to that in E. coli O9. Breakpoints were found in the wbdC gene and in the wzm or wzt gene. These findings suggested that the region from wzt to the 5′ half of wbdC in E. coli O9a might have been transferred from a certain Klebsiella O3 strain through recombination. This insertion might have produced a new O9a serotype in E. coli.

Different breakpoints were found in the connecting region between the wzm and wzt genes in two E. coli O9a strains, although putative recombination breakpoints in wbdC genes of four E. coli O9a strains were present at the same site. This might indicate that another recombination event had occurred in the wzm and wzt genes of E. coli O9a strains after the insertion of the wb* gene cluster of Klebsiella O3. Since these two E. coli O9a strains originally expressed group IA K antigen, these recombinations might cause the polymorphism in the chromosomal gnd-wb* region that was reported by Drummelsmith et al. (1).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AB000126, AB010150, AB009319 to AB009334, and AB010293 to AB010296.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Kato (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan), G. Schmidt (Forshungsinstitut Borstel, Borstel, Germany), I. Ørskov (E. coli Center, Copenhagen, Denmark), and F. Scheutz (Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark) for providing bacterial strains.

This work was supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation and by a Grant for Research Promotion of Aichi Medical University (to T.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Drummelsmith J, Amor P A, Whitfield C. Polymorphism, duplication, and IS1-mediated rearrangement in the chromosomal his-rfb-gnd region of Escherichia coli strains with group IA capsular K antigens. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3232–3238. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3232-3238.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson D P, Hayden J D, Quirke P. Extraction of nucleic acid from fresh and archival material. In: McPherson M J, Quirke P, Taylor G R, editors. PCR: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansson P-E, Lönngren J, Widmalm G, Leontein K, Slettgren K, Svensson S B, Wrangsell G, Dell A, Tiller P R. Structural studies of the O-antigen polysaccharides of Klebsiella O5 and Escherichia coli O8. Carbohydr Res. 1985;145:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayaratne P, Bronner D, MacLachlan P R, Dodgson C, Kido N, Whitfield C. Cloning and analysis of duplicated rfbM and rfbK genes involved in the formation of GDP-mannose in Escherichia coli O9:K30 and participation of rfb genes in the synthesis of the group I K30 capsular polysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3126–3139. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3126-3139.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kido N, Torgov V I, Sugiyama T, Uchiya K, Sugihara H, Komatsu T, Kato N, Jann K. Expression of the O9 polysaccharide of Escherichia coli: sequencing of the E. coli O9 rfb gene cluster, characterization of mannosyl transferases, and evidence for an ATP-binding cassette transport system. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2178–2187. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2178-2187.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kido N, Morooka N, Paeng N, Ohtani T, Kobayashi H, Shibata N, Okawa Y, Suzuki S, Sugiyama T, Yokochi T. Production of monoclonal antibody discriminating serological difference in Escherichia coli O9 and O9a polysaccharides. Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:519–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis, version 1.01. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paeng N, Kido N, Schmidt G, Sugiyama T, Kato Y, Koide N, Yokochi T. Augmented immunological activities of recombinant lipopolysaccharide possessing the mannose homopolymer as the O-specific polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1996;64:305–309. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.305-309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prehm P, Jann B, Jann K. The O9 antigen of Escherichia coli. Structure of the polysaccharide chain. Eur J Biochem. 1976;67:41–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves P R, Hobbs M, Valvano M A, Skurnik M, Whitfield C, Coplin D, Kido N, Klena J, Maskell D, Raetz C R H, Rick P D. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)82912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugiyama T, Kido N, Komatsu T, Ohta M, Jann K, Jann B, Saeki A, Kato N. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli O9 rfb: identification and DNA sequence of phosphomannomutase and GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase genes. Microbiology. 1994;140:59–71. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugiyama T, Kido N, Kato Y, Koide N, Yoshida T, Yokochi T. Evolutionary relationship among rfb gene clusters synthesizing mannose homopolymer as O-specific polysaccharides in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella. Gene. 1997;198:111–113. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugiyama, T., and N. Kido. Unpublished data.