Abstract

Oligoribonuclease, a 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease specific for small oligoribonucleotides, was purified to homogeneity from extracts of Escherichia coli. The purified protein is an α2 dimer of 40 kDa. NH2-terminal sequence analysis of the protein identified the gene encoding oligoribonuclease as yjeR (o204a), a previously reported open reading frame located at 94 min on the E. coli chromosome. However, as a consequence of the sequence information, the translation start site of this open reading frame has been revised. Cloning of yjeR led to overexpression of oligoribonuclease activity, and interruption of the cloned gene with a kanamycin resistance cassette eliminated the overexpression. On the basis of these data, we propose that yjeR be renamed orn. Orthologs of oligoribonuclease are present in a wide range of organisms, extending up to humans.

Oligoribonuclease is one of eight distinct 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases present in Escherichia coli (4, 12). The enzyme has been partially purified and shown to be highly specific for small oligoribonucleotides (3, 11). In this respect, it differs from all the other exoribonucleases, none of which can hydrolyze RNA molecules shorter than about 5 nucleotides (nt) in length (12). Oligoribonuclease is a processive enzyme that initiates attack at a free 3′ hydroxyl group on single-stranded RNAs, releasing 5′ mononucleotides in a sequential manner (3). Apparently, it is the smallest of the E. coli exoribonucleases, with a reported molecular weight of approximately 38,000 (11). Despite this information, and the fact that oligoribonuclease has been recognized for over 20 years (11), nothing is known about its cellular role, largely because of the unavailability of mutant strains deficient in the enzyme and the absence of any information about the gene that encodes oligoribonuclease.

As a first step toward elucidating the in vivo function of oligoribonuclease, we have purified the enzyme to homogeneity, obtained partial amino acid sequence information, and used this information to identify and clone the gene that encodes the protein. We report here that oligoribonuclease is encoded by the open reading frame previously designated yjeR (Swiss-Prot database accession no. P39287) or o204a (2), located at 94 min on the E. coli chromosome. This gene, which we have renamed orn, is a highly conserved member of the 3′-5′ exonuclease superfamily (9).

Purification of oligoribonuclease.

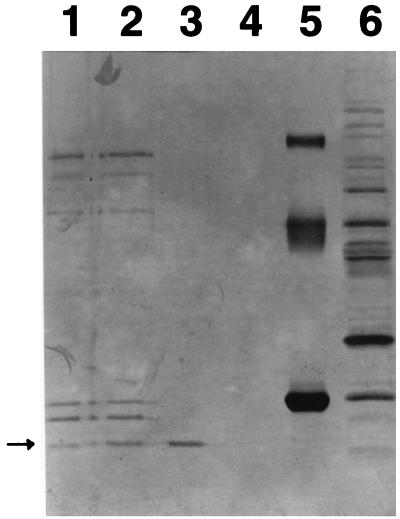

Oligoribonuclease was isolated from the high-speed supernatant fraction prepared from French press extracts of E. coli strain CA265II−, which is deficient in RNase II. Oligoribonuclease activity was monitored by the hydrolysis of [3H]oligo(U) (average chain length, ≈3), essentially as described previously (4, 11). Homogeneous oligoribonuclease was obtained by a purification scheme that included ammonium sulfate fractionation, followed by chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex, hydroxylapatite, Ultrogel AcA54, and Affi-Gel Blue. The final preparation obtained with this procedure contained only a single protein with an apparent molecular mass of 20 kDa (Fig. 1, lane 3) based on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Inasmuch as the gel filtration chromatography on Ultragel AcA54 indicated that the native enzyme was approximately 40 kDa in size, in close agreement with the size reported earlier (11), these data suggest that oligoribonuclease is an α2 dimer.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of purified oligoribonuclease. Samples from the Affi-Gel Blue column were concentrated 5- to 10-fold with a Centricon-10 membrane and analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel. Lane 1, Affi-Gel Blue flowthrough; lane 2, Affi-Gel Blue wash; lane 3, Affi-Gel Blue oligoribonuclease peak activity fraction; lane 4, Affi-Gel Blue fractions before activity peak; lane 5, standards; bovine serum albumin (68,000 Da), ovalbumin (44,000 Da), and chymotrypsinogen (24,500 Da); lane 6, DEAE-Sephadex combined activity peak fractions. The arrow indicates the position of the oligoribonuclease subunit.

A second, larger-scale purification was also carried out to provide sufficient oligoribonuclease for microsequencing. However, this preparation showed two bands on SDS–12% PAGE in the 20-kDa region. Since it was not possible to conclusively determine which of the two proteins corresponded to oligoribonuclease, both bands were transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane and washed and stained according to the procedure of LeGendre and Matsudaira (10).

Although the two purifications of oligoribonuclease carried out as part of this study resulted in either homogeneous or highly purified enzyme, our experience with the procedure is not sufficient to warrant a detailed description here. A more complete description of the purification protocol will be presented elsewhere once it has been refined.

N-terminal sequence analysis.

Gas-phase sequencing on an Applied Biosystems 491 protein sequencer was used to determine the amino-terminal residues of each of the two purified proteins. For one band, the sequence was determined to be MTATAQQ which, based on a TFASTA analysis of the GenBank database (6), corresponded to the first seven amino acids of adenine phosphoribosyltransferase, encoded by the apt gene at 10 min on the E. coli chromosome. The amino-terminal sequence of the second band was found to be SANENNLIWIDLE, which was identical to residues 25 to 37 of a hypothetical protein encoded by yjeR (o204a) (2), an unidentified open reading frame located at 94 min on the E. coli chromosome. Based on this sequence information, we propose that the reading frame of yjeR be corrected. It is likely that the true coding region actually begins at the methionine in position 24 rather than at the methionine 23 residues upstream, as originally suggested (2). In addition to the protein sequence data, there is no Shine-Dalgarno sequence upstream of the first potential initiator codon, whereas one is present before the codon specifying methionine 24. Assuming the latter translation initiation site, only a single methionine residue would have to be removed to generate the NH2-terminal sequence actually observed for the purified protein. The resulting 180-amino-acid protein would have a calculated molecular weight of 20,684, in close agreement with the SDS-PAGE data.

Cloning of the gene encoding oligoribonuclease.

To determine which of the two genes, apt or yjeR, is responsible for oligoribonuclease activity, each of them was cloned into plasmid pUC19 for measurement of oligoribonuclease overexpression. To accomplish this, clones 12H5 (no. 152) and 3H6 (no. 651) from the E. coli genomic library of Kohara et al. (8), containing apt and yjeR, respectively, were subjected to PCR amplification. Primers, containing linkers cleavable by the restriction enzymes XbaI and KpnI, were designed to flank the apt and yjeR genes. After 30 cycles with Taq DNA polymerase, the resulting apt (0.86 kb) and yjeR (1.3 kb) PCR amplification products were each digested with the restriction enzymes XbaI and KpnI and cloned into the high-copy-number vector pUC19. The resulting plasmids, pAT19, carrying the apt gene, and pYJ19, carrying the yjeR gene, were each transformed into strain CA265II− for subsequent measurement of oligoribonuclease activity.

Cells were grown in yeast extract-tryptone medium to an A550 of ≈1. Cultures (50 ml each) were centrifuged, and cells were resuspended in a solution of 1.5 ml of Tris-HCl (pH 7.9) (10 mM), MgCl2 (10 mM), NH4Cl (20 mM), and glycerol (10%). Extracts were prepared by sonication, and cellular debris was removed by centrifugation. An assay of the extracts for oligoribonuclease activity (Table 1) revealed that overexpression was associated only with the presence of plasmid pYJ19 carrying the yjeR gene. Overexpression values as much as 50-fold more than those for the pUC19 vector alone were obtained by this procedure. To further substantiate the encoding by yjeR of oligoribonuclease, pYJ19 was cleaved with BamHI, and the 4-nt recessed 3′ termini were filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I to produce blunt ends. The kanamycin resistance cassette from plasmid pUC4K (Pharmacia), treated in the same manner, was inserted into yjeR by blunt-ended ligation. The resulting plasmid, pYJ-Kan, when grown in strain CA265II−, did not lead to overexpression of oligoribonuclease activity (Table 1). These data show that the 1.3-kb fragment carrying yjeR is directly responsible for oligoribonuclease overexpression. On the basis of this finding and on the finding that one of the two proteins in the highly purified oligoribonuclease preparation is YjeR, we conclude that yjeR encodes oligoribonuclease and propose that it be renamed orn.

TABLE 1.

Association of oligoribonuclease activity with the yjeR gene

| Expt no. | Plasmid present | Oligoribonuclease activity (nmol/20 min/mg of protein)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| pUC19 | 95 | |

| pAT19 | 84 | |

| pYJ19 | 5,500 | |

| 2 | ||

| None | 32 | |

| pYJ19 | 3,900 | |

| pYJ-Kan | 28 |

Extracts were prepared from strain CA265II− as described in the text. Assays were carried out for 20 min at 37°C with ≈1 μg of cell extract with [3H]oligo(U) (average chain length, ≈3) as substrate. Assay conditions and analysis of the products were as described previously (3).

Sequence analysis of orn and oligoribonuclease.

Based on the NH2-terminal sequence information presented above, the coding region of the orn gene encompasses a region of 543 nt that begins with an AUG initiator codon and ends at a UAA termination codon. Four to ten nucleotides upstream of the AUG codon is a purine-rich region that could serve as a Shine-Dalgarno sequence. Immediately upstream of orn is an unidentified open reading frame, yjeQ or f337 (2), that is transcribed in the opposite direction. Approximately 135 nt of intergenic spacer is present between the orn and yjeQ coding sequences. Interestingly, no recognizable ς70 promoter sequence is found within this region. Whether orn might be under the control of a different sigma factor and where its transcription start site is located remain to be determined.

The orn gene would encode a polypeptide of approximately 20,700 Da, in excellent agreement with the size of the purified protein by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). This subunit is the smallest in the known E. coli exoribonucleases. Based on its deduced amino acid sequence, oligoribonuclease is an acidic protein with a pI of approximately 5.0. However, the distribution of acidic and basic residues is distinctly nonrandom. While the N-terminal half of the protein is extremely acidic, the C-terminal half is basic. This observation, coupled with the fact that all the aromatic amino acid residues (F plus Y) are located in the C-terminal portion of the protein, strongly suggests that this part of oligoribonuclease contains its RNA-binding domain.

Of considerable interest, and as recently pointed out by Koonin (9), oligoribonuclease is a highly conserved protein and a member of the superfamily of 3′-5′ exonucleases. Although it is now clear that YjeR is an oligoribonuclease, rather than a DNA exonuclease as suggested previously (9), its function is entirely consistent with those of other members of this superfamily. Based on BLASTP searches (1) of the GenBank and GenBank EST databases, the subfamily of oligoribonuclease orthologs includes members from Haemophilus influenzae, Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans (and two other nematodes, Brugia malayi and Pristionchus pacificus), and Drosophila melanogaster and mice, rats, and humans. Orthologs were also found in Neisseria meningitidis (7a) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (11a). The degree of identity between the E. coli and the higher eukaryotic homologs approaches 50%, suggesting that oligoribonuclease function may have been highly conserved among all of these species.

The cellular role of oligoribonuclease is not yet known. Its catalytic properties in vitro suggest that its function is limited to the removal of small oligoribonucleotides, perhaps those left over during the degradation of mRNA. It is interesting that oligoribonuclease orthologs are not present in the sequenced archael genomes, in mycoplasma, in the cyanobacteria Synechocystis species, or in Bacillus subtilis. It is known that the mode of mRNA degradation in B. subtilis differs from that in E. coli (reference 5 and references therein), and this may account for its lack of an oligoribonuclease requirement. Preliminary attempts to incorporate an interrupted orn gene into the E. coli chromosome by linear transformation with pYJ-Kan have so far been unsuccessful (7), raising the possibility that oligoribonuclease is an essential enzyme in E. coli. Studies to conclusively answer this question are currently under way.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The new information regarding the size of YjeR has been deposited in the Swiss-Prot database (accession no. P39287).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant GM16317 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Kenneth Rudd for assistance with computer analysis and Kenneth Rudd and Zhongwei Li for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PS1-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burland V, Plunkett III G, Sofia H J, Daniels D L, Blattner F R. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome VI: DNA sequence of the region from 92.8 through 100 minutes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2105–2119. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datta A K, Niyogi S K. A novel oligoribonuclease of Escherichia coli II. Mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7313–7319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deutscher M P. Promiscuous exoribonucleases of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4577–4583. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4577-4583.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutscher M P, Reuven N B. Enzymatic basis for hydrolytic versus phosphorolytic mRNA degradation in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3277–3280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh, S., and M. P. Deutscher. Unpublished data.

- 7a.The Institute for Genomic Research. Personal communication.

- 8.Kohara Y, Akiyama K, Isono K. The physical map of the whole E. coli chromosome: application of a new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell. 1987;50:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koonin E V. A conserved ancient domain joins the growing superfamily of 3′-5′ exonucleases. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R604–R606. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeGendre N, Matsudaira P T. Purification of proteins and peptides by SDS-PAGE. In: Matsudaira P T, editor. A practical guide to protein and peptide purification for microsequencing. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niyogi S K, Datta A K. A novel oligoribonuclease of Escherichia coli I. Isolation and properties. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7307–7312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Roe, B. A., S. Difton, and D. W. Dyer. Personal communication.

- 12.Yu D, Deutscher M P. Oligoribonuclease is distinct from the other known exoribonucleases of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4137–4139. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4137-4139.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]