Abstract

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) adults experience a wide variety of unique challenges accessing healthcare. These barriers may be exacerbated among older LGBTQ+ people due to intersecting, marginalized identities. To prepare physicians to address the healthcare needs of older LGBTQ+ adults, graduate medical education (GME) must include training about the specific needs of this population. Prior studies demonstrate a lack of LGBTQ+ training in GME curricula. Here, we investigated the presence of LGBTQ+ curricula in internal medicine residencies and geriatrics fellowships through a national survey. Over 62.0% of internal medicine (n = 49) and 65.6% (n = 21) of geriatric medicine fellowship program directors, responding to the survey, reported content relevant to the health of older LGBTQ+ adults. Education about LGBTQ+ health in internal medicine residencies and geriatrics fellowships is vital for the provision of culturally-competent healthcare and to create an inclusive environment for older LGBTQ+ patients.

Keywords: graduate medical education, geriatric fellowship, LGBTQ+, curriculum, health disparities

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) individuals experience a variety of unique healthcare challenges that their heterosexual and/or cisgender peers may not ( National Academies Press, 2020). Concerns regarding stigma and discrimination may act as barriers to care (Casey et al., 2019; Macapagal, Bhatia, & Greene, 2016) and be exacerbated among older LGBTQ+ adults due to multiple, intersecting, marginalized identities (Gardner, de Vries, & Mockus, 2014). The American Geriatrics Society released a statement acknowledging the discrimination faced by older LGBTQ+ adults and describing goals to provide equitable care (Hurd, 2015).

Individuals over the age of 65 are one of the fastest growing demographics in the U.S., with estimates that older adults will outnumber children by 2034 (Vespa, Medina, & Armstrong, 2020). Quantifying the number of LGBTQ+ identified older adults historically has been difficult to assess due to less willingness compared to younger people to be “out” about their gender identity or sexual orientation (D’augelli & Grossman, 2001). This is likely secondary to fears of harassment and discrimination as well as the long-lasting impacts of the stigma placed on the LGBTQ+ population, especially for a generation that grew up when homosexuality was considered to be a mental illness (Brotman et al., 2003). Despite this difficulty, it is expected that there will be nearly 7 million LGBTQ+ adults over 50 years of age in the United States by 2030 (Streed et al, 2021a). To address the healthcare needs and health disparities experienced by older LGBTQ+ adults, GME programs must include training about this growing population.

Older LGBTQ+ adults have distinct health care needs. They are more likely to experience poverty and have more physical and mental health conditions (Choi & Meyer, 2016). Over half of LGBTQ+ individuals have faced bias or discrimination as part of their interactions with the healthcare system (Hurd, 2015; Preston, 2022). Fear of discrimination can result in the delay or avoidance of health care (Hurd, 2015). Older LGBTQ+ adults may also feel the need to hide their identity in healthcare or long-term care settings, and may not have legal relationships with their partners because of past discrimination or stigma. They may want to involve “chosen family” and friends in their care, instead of legal or biological relatives (Hurd, 2015). LGBTQ+ older adults are more likely to experience social isolation and loneliness, and to worry about having adequate support from family and friends (Fasullo et al., 2021; Freedman, 2020; Preston, 2022). They are also more likely to rely on long-term care facilities (Fasullo et al., 2021).

Prior studies have indicated that there is a lack of formal LGBTQ+ health training across the GME curricula and within the multidisciplinary healthcare team (ACGME, 2020; ACGME 2022a; ACGME 2022b; Gardner et al., 2014; Kortes-Miller, Wilson, & Stinchcombe, 2019). The absence of formal training results in physicians who have not acquired basic knowledge on LGBTQ+ health topics, which may negatively affect patient care (Hurd, 2015). The need for formal training was demonstrated by a recent study showing that senior residents in internal medicine had poor knowledge about sexual and gender minority health and health disparities, despite several years of residency training (Streed et al., 2021b). Basic knowledge of health topics and disparities is necessary for the provision of competent care. Surveys of residents demonstrate that they feel unprepared and uncomfortable treating LGBTQ+ patients and would like training in LGBTQ+ health topics (Guerrero-Hal, 2021; Hayes et al., 2015; Moll et al., 2019; Roth et al., 2021; Streed et al., 2019).

The American Geriatrics Society position statement on care of older LGBTQ+ adults identifies education for healthcare providers on “LGBT health concerns focused on the older adult population, the effect of discrimination on healthcare delivery, the social circumstances of LGBT individuals, and the relationship between social history (including gender identity, relationship status, and sexual behavior) and health and health care” as one of the most important steps for the delivery of high-quality health care (Hurd, 2015). Recently, the American Geriatrics Society has been joined by several medical societies and other members of the GME community in calling for training that is responsive to the health needs of the LGBTQ+ community (Hurd, 2015; Pregnall, Churchwell, & Ehrenfeld, 2021; Roth et al., 2021; Streed et al., 2021b). Despite these calls, no formal curricula on LGBTQ+ health is required as part of internal medicine residency or geriatric fellowship training (ACGME, 2020; ACGME 2022a, 2022b). Several residency programs have independently developed their own LGBTQ+ curricula (Barrett et al., 2021; Grova et al., 2021; Klein & Nakhai, 2016; Roth et al., 2021; Streed et al., 2021b); however, the lack of a formal curricula or guidance from the ACGME, means that residency and fellowship programs incorporate content on LGBTQ+ health topics inconsistently.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have specifically investigated whether GME programs include training about the health of older LGBTQ+ adults. In the present study, we investigated the presence of LGBTQ+ health curricula in internal medicine and geriatrics GME training programs.

Materials and Methods

Population & Survey Procedure

Briefly, an online survey was distributed to program directors (PDs) of internal medicine residency programs and geriatric medicine fellowships in the U.S. between August-October 2020. Contact information for PDs was identified through the publicly available Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access (FREIDA) hosted by the American Medical Association. The survey was administered online via Qualtrics® (Provo, UT). The risk of duplicate entries was mitigated by sending a unique link to each PD, which prevented the survey from being reopened once completed. Additionally, reminder emails were only sent to PDs who had not completed the survey in order to avoid duplicate responses.

The survey instrument contained 9 questions, taking 5 minutes to complete, and was composed of two sections. The first inquired about inclusion of specific curriculum content items related to the health and healthcare of older LGBTQ+ adults including both medical topics, such as managing gender-affirming hormones, and psychosocial topics, such as social isolation, depression, and poverty. PDs were asked to indicate (yes/no) whether the didactic curriculum of their program included each listed item. The second captured program demographic information, including geography and affiliation. We also asked PDs whether their residency had self-identified ‘out’ LGBTQ+ faculty members and trainees.

Previously published surveys on LGBTQ+ health topics in GME curricula the LGBTQ+ care competencies set by the AAMC were used to craft the survey items (Goetz et al., 2020; Hirschtritt et al., 2019; Jia et al., 2020; Moll et al., 2014; Moll et al., 2019; Morrison et al., 2017). A team of physicians with content expertise in GME program leadership and LGBTQ+ health reviewed, revised, and approved the final survey items. Full details of the study procedure have been previously published (Bunting et al., n.d.).

Frequencies were calculated to evaluate the percentages of internal medicine residencies and geriatric medicine fellowships that included didactic training about the listed items. All data was managed utilizing IBM SPSS v27 (Armonk, NY). This study was reviewed and granted exempt status by the Institutional Review Board of Rosalind Franklin University.

Results

Program Demographics

A total of 526 internal medicine and 148 geriatric PDs were sent a survey yielding 111 completed survey responses , representing 79 PDs in internal medicine (response rate = 15.0%) and 32 PDs of geriatric medicine fellowships (response rate = 21.5%). Most of the geriatric medicine fellowships were university-based (n=22, 71%) in urban settings (n=21, 72%). Internal medicine programs were generally community based/university affiliated (n=31, 40%) in urban settings (n=42, 55%). Full demographic information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information (N=111)

| Geriatrics | Internal Medicine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography | n | % | n | % |

| Rural | 2 | 6.9% | 9 | 11.7% |

| Suburban | 6 | 20.7% | 26 | 33.8% |

| Urban | 21 | 72.4% | 42 | 54.5% |

| Program Affiliation | ||||

| Community Based | 2 | 6.50% | 22 | 28.6% |

| University Based | 22 | 71.0% | 24 | 31.2% |

| Community Based/University Affiliated | 7 | 22.6% | 31 | 40.3% |

| Region | ||||

| South | 10 | 31.3% | 25 | 31.6% |

| Northeast | 8 | 25.0% | 24 | 30.4% |

| West | 5 | 15.6% | 14 | 17.7% |

| Midwest | 9 | 28.1% | 16 | 20.3% |

| Out Faculty | ||||

| No/Unsure | 14 | 43.80% | 33 | 41.8% |

| Yes | 18 | 56.30% | 46 | 58.2% |

| Out Residents | ||||

| No/Unsure | 23 | 71.9% | 28 | 35.4% |

| Yes | 9 | 28.1% | 51 | 64.6% |

Of the geriatric medicine fellowship programs completing the survey, 18 PDs (56.3%) identified the presence of “out” faculty and 9 (28.1%) reported “out” fellows. Of the internal medicine PD respondents, 46 (58.2%) reported “out” faculty and 51 (64.6%) reported “out” residents.

Didactic Curricular Content

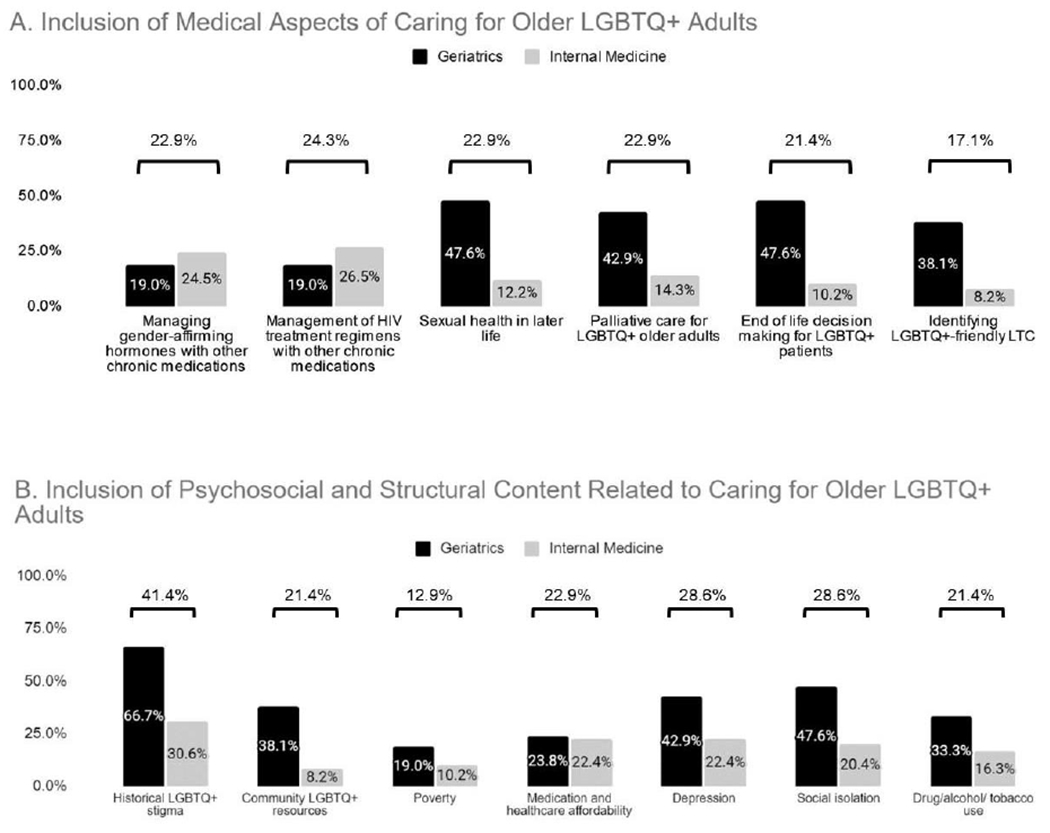

Overall, we found that a majority of survey respondents from internal medicine (n = 49, 62.0%) and geriatric medicine fellowship PDs (n = 21, 65.6%) reported including didactic content on the health of older LGBTQ+ adults (Figure 1). The most frequently included medical topic for older LGBTQ+ adults was co-management of HIV treatment regimens and other chronic medications (IM: n=13, 26.5%; Geriatrics: n=4, 19% ). Of the programs completing the survey, IM programs were less likely to address identification of LGBTQ+-friendly long-term care (LTC) facilities (IM: n=4, 8.2%; Geriatrics: n=8, 38.1%) and end-of-life decision making (IM: n=5, 10.2%; Geriatrics: n=10, 47.6%) compared to geriatric programs (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Inclusion of Curricular Content Related to Caring for Older LGBTQ+ Adults.

Comparison of the percentages of PDs who indicated their residency/fellowship program included didactic content about (A) medical, and (B) psychosocial and structural aspects of caring for older LGBTQ+ adults.

We inquired about inclusion of content related to the psychosocial and structural aspects of healthcare for older LGBTQ+ adults such as poverty, social isolation, and healthcare affordability. Across all psychosocial items, a greater percentage of geriatrics PD survey respondents reported content about the psychosocial aspects of caring for older LGBTQ+ adults. The most frequently included item in this domain was the historical stigma of identifying as an LGBTQ+ person, included by 66.7% (n=14) of geriatrics fellowships and 30.6% (n=15) of internal medicine residencies responding. The least frequently included item was poverty among older LGBTQ+ adults, which was included in the didactic curriculum of 19.0% (n=4) of geriatrics training programs and 10.2% (n=5) of internal medicine programs responding to the survey (Figure 1B).

Discussion

The aging LGBTQ+ community has distinct health needs and physicians are not receiving the training in LGBTQ+ health topics and disparities to meet those needs. Discrimination in healthcare settings is a common experience for the LGBTQ+ community and many fear mistreatment in long-term care facilities (Hurd, 2015; Preston, 2022; Putney et al., 2018). Healthcare forms and policies are based on heteronormative assumptions. Older LGBTQ+ adults may find that their partners are not allowed to visit because of hospital policies or that the forms do not reflect their legal name and gender (Adams, 2022; Hurd, 2015). Older transgender adults face additional barriers accessing long-term care facilities and may feel the need to hide their identity (Adams, 2022; Hurd, 2015; Putney et al., 2018). Older LGBTQ+ adults are more likely to be socially isolated and this experience is exacerbated by long-term care facilities where they are forced to hide their identity or are separated from their chosen family and LGBTQ+ community (Adams, 2022; Hurd, 2015; Putney et al., 2018).

Recognizing the distinct health needs of the LGBTQ+ community, the GME community and several medical societies have called for increased training on LGBTQ+ health for health professionals (Hurd, 2015; Pregnall, Churchwell, & Ehrenfeld, 2021; Roth et al., 2021; Streed et al., 2021b). Recently, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation highlighted work with the LGBTQ+ community as part of their Trust Practice Challenge (Wolfson, 2019). Pregnall and colleagues (2021) called on the ACGME to include LGBTQ+ health topics in order to address the 2018 ACGME common program requirement related to the treatment of diverse populations. They argued that it is important to include core knowledge on LGBTQ+ health across residency training since it relates to a large number of diverse specialties and that some programs will not provide education on LGBTQ+ health topics unless the ACGME requires it (Pregnall et al., 2021). Beyond calling for change, several groups have suggested specific ways to improve healthcare for older LGBTQ+ adults. The American Geriatric Society described three areas of focus to reduce discrimination including the evaluation of policies to ensure equitable treatment, education for healthcare professions on LGBTQ+ health topics, and recognition and responsiveness to the distinct health care needs and social situations of LGBTQ+ adults (Hurd, 2015). Streed and colleagues (2021b) discussed how academic medical centers can advance LGBTQ+ health through their clinical care, education, and research missions. Their suggestions included sexual health and gender minority patient panels and electives for residents and fellows, LGBTQ+ case conferences, specialty-specific clinical training related to LGBTQ+ health, LGBTQ+ health track, and research opportunities related to LGBTQ+ health and education (Streed et al., 2021b). In Massachusetts, a 2018 state law requires that individuals providing services to older adults who are licensed or receive state funding must complete training on the needs of LGBTQ+ older adults (Streed et al., 2021a). An online module designed to improve the care of LGBTQ+ older adults and address the state requirements showed an increase in knowledge across topics such as relevant terminology and history, understanding relationship structures, and recognizing resources (Streed et al., 2021a). In addition to these models, there are numerous studies within internal medicine evaluating GME curricula or modules designed to increase residents’ knowledge, comfort, and confidence in LGBTQ+ health topics (Pregnall et al., 2021). Despite these calls and models, we found that there are still gaps in GME training related to the health of older LGBTQ+ adults, providing specific targets for improvements in GME curricula (ACGME, 2022).

As previously reported in a study of GME curriculum regarding LGBTQ+ health overall, the primary focus of the LGBTQ+ didactic curriculum focused on older adults was sexual health (Bunting et al., n.d.). While over half of the geriatric fellowship programs included topics related to end of life decision making, palliative care, and identification of LGBTQ+ friendly LTC venues, these topics were less frequently addressed by internal medicine programs. It is possible that the patient and family-centered goals of care discussions common in geriatrics training create space for conversations related to LGBTQ+ health more often than in internal medicine, which is often more focused on the medical management. This discrepancy is important because even physicians who do not sub-specialize in geriatrics following their training will encounter older LGBTQ+ adults in practice. Given that older adults are projected to outnumber children by 2034, all physicians should be educated on the needs of older LGBTQ+ adults (Vespa et al., 2020).

Psychosocial and structural barriers were generally under-represented in the GME curricula of both specialties, despite known disparities specific to the LGBTQ+ community such as poverty, stigma, depression, and social isolation (Valenti et al., 2020). These important topics, which are especially relevant to the older LGBTQ+ community, were only covered in about 50% of responding programs.

Palliative care and end of life decision making are especially important topics within the LGBTQ+ community (Acquaviva, 2017). Given the prevalence of stigma and discrimination, historical and present, many older LGBTQ+ individuals fear engaging with the healthcare system (Blendon & Casey, 2019; Dickson et al., 2021; Kortes-Miller, Boulé, Wilson, & Stinchcombe, 2018). Similarly, many LGBTQ+ individuals may wish to prioritize their families of choice over their legal families in terms of decision making, which runs counter to the current medical ethics recommendations (Dickson et al., 2020; Wahlert & Fiester, 2012). Guidance about how to navigate the medical-legal system, so that partners and friends can play an active role in decision making, as necessary, is an especially important training topic in this context. Discussions around aging, palliative care, and end of life decision making need to be sensitive to the unique concerns and needs of the LGBTQ+ community (Acquaviva, 2017).

Physicians have an important role in supporting the health and needs of older LGBTQ+ patients (Hurd, 2015; Maingi et al., 2021). Education in LGBTQ+ health topics is vital for the provision of high-quality and comprehensive healthcare, and also for creating the safe and inclusive environment that patients need to have conversations about their health, goals of care, and end of life decisions (Pecanac, Hill, & Borkowski, 2021). There are numerous educational resources that could be used to inform and expand didactic and clinical training on LGBTQ+ health (Greene, Hanley, Cook, Gillespie, & Zabar, 2017; Pregnall et al., 2021; Streed & Davis, 2018; Streed et al., 2021a; Ufomata et al., 2018), including resources dedicated to topics such as hospice and palliative care (Acquaviva, 2017). Similarly, there are numerous models describing how LGBTQ+ curricula and competencies can be woven into residency and fellowship training (Hurd, 2015; Pregnall et al., 2021; Streed et al., 2021b). Despite the existence of curricula and models for inclusion, educational content related to the health of older LGBTQ+ adults is not consistently taught as part of internal medicine or geriatric training. It is imperative that this content be included in graduate medical education to ensure comprehensive and high-quality healthcare and services for older LGBTQ+ adults.

Currently, LGBTQ+ health content is most likely to be incorporated into graduate medical education when there is a faculty or trainee champion. To truly integrate LGBTQ+ content into graduate medical education, a more systematic and national approach is necessary (Pregnall et al., 2021). Unfortunately, the largest barrier to education on LGBTQ+ topics at this time is the politicization of gender-affirming and LGBTQ+ health care. Instead of reducing barriers to healthcare, older LGBTQ+ adults across the United States are facing increased stigma and discrimination, and new legal and financial barriers to accessing healthcare. The new barriers to healthcare will only exacerbate existing disparities and worsen physical and mental health outcomes for older LGBTQ+ adults. Residency and fellowship programs can still integrate LGBTQ+ curricula and evaluate its effectiveness, adapting the sessions as needed to improve the quality of training and ultimately patient care. An iterative approach to LGBTQ+ health curricula development across different specialties and programs will ensure that there are generalizable and evidence-based curricula available for adoption once national requirements and competencies are established.

Limitations

There are several limitations to consider. First, the study used an anonymous survey instrument; therefore, we cannot confirm reported didactic content through program websites. Second, it is possible that the surveys were more likely to be completed by PDs interested in LGBTQ+ health, resulting in response bias. If this is the case, then the gaps in LGBTQ+ didactic content may be greater than described. Third, we have a low response rate and as a result, our findings do not adequately reflect the full range of programs. Despite the low response rate, we captured program diversity in terms of geography and program affiliation. The inclusion of program types from all regions increases the generalizability of our findings. Finally, we are only reporting on the frequency with which PDs recall LGBTQ+ topics taught in their program. We still do not know the number of hours dedicated to instruction for each topic, the breadth of the content, how the content is taught, nor the quality of the curricula that is presented. More research is needed in this area.

Conclusion

The number of older LGBTQ+ adults is increasing and estimated to be almost 7 million by 2030. Despite the ACGME updating their requirements to include competencies related to the treatment of diverse populations and calls from the GME community and medical societies for improved education on LGBTQ+ health topics, our results suggest that educational content on the health of older LGBTQ+ adults is not universally taught as part of internal medicine and geriatric training. To meet the needs of the growing, aging population as well as and the shortage of fellowship-trained geriatricians, it is imperative for all physicians to be educated on the needs of older LBGTQ+ adults. There is an opportunity for internal medicine and geriatric programs to develop curricula on the distinct health needs of older LGBTQ+ adults, rigorously evaluate the curricula and adapt accordingly, and share it with other programs for implementation. The creation of standardized, evidence-based training that can be implemented across all programs is important to ensure that all physicians receive the training they need to provide comprehensive and high-quality care to older LGBTQ+ adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the PDs who took time to complete this study. We would also like to thank Drs. Glenn Rosenbluth and Sarah Schaeffer for reviewing earlier drafts of the survey instrument.

Declaration of interest statement

MCM has support from the National Institute of Mental Health under Award F30MH118762. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

In accordance with IRB stipulations, data will not be posted online but can be made available at request.

References

- ACGME. (2022a). ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf

- ACGME. (2022b). ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Internal Medicine. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/140_internalmedicine_2022v4.pdf

- ACGME. (2020). ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Geriatric Medicine. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/125_GeriatricMedicine_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-23-055053-010&ver=2020-06-23-055053-010

- Acquaviva KD (2017). LGBTQ-inclusive hospice and palliative care : a practical guide to transforming professional practice. Columbia University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M (2022). Addressing Access and Inclusion for LGBTQ+ Older Adults in Long-Term Care Communities and Older Adult Housing. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(9), 1437–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett DL, Supapannachart KJ, Caleon RL, Ragmanauskaite L, McCleskey P, & Yeung H (2021). Interactive Session for Residents and Medical Students on Dermatologic Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Patients. MedEdPORTAL : the journal of teaching and learning resources, 17, 11148. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon R, & Casey L (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Perspectives for the future. Health Services Research, 54 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 1467–1471. 10.1111/1475-6773.13218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, & Cormier R (2003). The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting S, Goetz T, Gabrani A, Blansky B, Marr M, & Sanchez N (n.d.). Evaluation of the Inclusion of Training about Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ+) in Primary Care Graduate Medical Education Programs: A National Survey of Program Directors. Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health. [Google Scholar]

- Casey LS, Reisner SL, Findling MG, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Sayde JM, & Miller C (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1454–1466. 10.1111/1475-6773.13229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SK, & Meyer IH (2016). LGBT aging: A review of research findings, needs, and policy implications. eScholarship, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- D’augelli AR, & Grossman AH (2001). Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of interpersonal violence, 16(10), 1008–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson L, Bunting S, Nanna A, Taylor M, Hein L, & Spencer M (2020). Appointment of a Healthcare Power of Attorney Among Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Adults in the Southern United States. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 10.1177/1049909120979787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson L, Bunting S, Nanna A, Taylor M, Spencer M, & Hein L (2021). Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Adults’ Experiences With Discrimination and Impacts on Expectations for Long-Term Care: Results of a Survey in the Southern United States. Journal of Applied Gerontology : The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society. 10.1177/07334648211048189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman A, & Nicolle J (2020). Social isolation and loneliness: the new geriatric giants: Approach for primary care. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 66(3), 176–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner AT, de Vries B, & Mockus DS (2014). Aging Out in the Desert: Disclosure, Acceptance, and Service Use Among Midlife and Older Lesbians and Gay Men. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1). 10.1080/00918369.2013.835240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz TG, Nieman CL, Chaiet SR, Morrison SD, Cabrera-Muffly C, & Lustig LR (2021). Sexual and Gender Minority Curriculum Within Otolaryngology Residency Programs. Transgender Health, 6(5), 267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RE, Hanley K, Cook TE, Gillespie C, & Zabar S (2017). Meeting the Primary Care Needs of Transgender Patients Through Simulation. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(3), 380. 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00770.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grova MM, Donohue SJ, Bahnson M, Meyers MO, & Bahnson EM (2021). Allyship in Surgical Residents: Evidence for LGBTQ Competency Training in Surgical Education. The Journal of surgical research, 260, 169–176. 10.1016/j.jss.2020.11.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Hall KD, Muscanell R, Garg N, Romero IL, & Chor J (2021). Obstetrics and Gynecology Resident Physician Experiences with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Healthcare Training. Medical science educator, 31(2), 599–606. 10.1007/s40670-021-01227-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes V, Blondeau W, & Bing-You RG (2015). Assessment of Medical Student and Resident/Fellow Knowledge, Comfort, and Training With Sexual History Taking in LGBTQ Patients. Family medicine, 47(5), 383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschtritt ME, Noy G, Haller E, & Forstein M (2019). LGBT-specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Academic Psychiatry, 43(1), 41–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd Z (2015). American geriatrics society care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults position statement: American geriatrics society ethics committee. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(3). 10.1111/jgs.13297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia JL, Nord KM, Sarin KY, Linos E, & Bailey EE (2020). Sexual and gender minority curricula within US dermatology residency programs. JAMA dermatology, 156(5), 593–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein EW, & Nakhai M (2016). Caring for LGBTQ patients: Methods for improving physician cultural competence. International journal of psychiatry in medicine, 51(4), 315–324. 10.1177/0091217416659268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortes-Miller K, Boulé J, Wilson K, & Stinchcombe A (2018). Dying in Long-Term Care: Perspectives from Sexual and Gender Minority Older Adults about Their Fears and Hopes for End of Life. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Care, 14(2–3), 209–224. 10.1080/15524256.2018.1487364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortes-Miller K, Wilson K, & Stinchcombe A (2019). Care and LGBT Aging in Canada: A Focus Group Study on the Educational Gaps among Care Workers. Clinical Gerontologist, 42(2), 192–197. 10.1080/07317115.2018.1544955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal K, Bhatia R, & Greene GJ (2016). Differences in Healthcare Access, Use, and Experiences Within a Community Sample of Racially Diverse Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Emerging Adults. LGBT Health, 3(6), 434. 10.1089/LGBT.2015.0124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingi S, Radix A, Candrian C, Stein G, Berkman C, & O’Mahony S (2021). Improving the Hospice and Palliative Care Experiences of LGBTQ Patients and Their Caregivers. Primary Care, 48(2), 339–349. 10.1016/J.POP.2021.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, Joyce C, & Moreno-Walton L (2019). Attitudes, behavior, and comfort of emergency medicine residents in caring for LGBT patients: what do we know?. AEM education and training, 3(2), 129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, Lee B, Slaven E, James T, … & Heron SL (2014). The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know?. Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(5), 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SD, Dy GW, Chong HJ, Holt SK, Vedder NB, Sorensen MD, … & Friedrich JB (2017). Transgender-related education in plastic surgery and urology residency programs. Journal of graduate medical education, 9(2), 178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Understanding the well-being of LGBTQI+ populations.

- Pecanac K, Hill M, & Borkowski E (2021). “It Made Me Feel Like I Didn’t Know My Own Body”: Patient-Provider Relationships, LGBTQ+ Identity, and End-of-Life Discussions. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 38(6), 644–649. 10.1177/1049909121996276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pregnall A, Churchwell A, & Ehrenfeld J (2021). A Call for LGBTQ Content in Graduate Medical Education Program Requirements. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 96(6), 828–835. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston R (2022). Quality of Life among LGBTQ Older Adults in the United States: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 10783903221127697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JM, Keary S, Hebert N, Krinsky L, & Halmo R (2018). “Fear Runs Deep:” The Anticipated Needs of LGBT Older Adults in Long-Term Care. Journal of gerontological social work, 61(8), 887–907. 10.1080/01634372.2018.1508109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth LT, Catallozzi M, Soren K, Lane M, & Friedman S (2021). Bridging the Gap in Graduate Medical Education: A Longitudinal Pediatric Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning Health Curriculum. Academic pediatrics, 21(8), 1449–1457. 10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streed CG, & Davis JA (2018). Improving Clinical Education and Training on Sexual and Gender Minority Health. Current Sexual Health Reports 2018 10:4, 10(4), 273–280. 10.1007/S11930-018-0185-Y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Streed CG Jr, Gouskova N, Rice M, & Paasche-Orlow S (2021a). Pilot study of senior care organization staff knowledge about sexual and gender minority older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(7), E17–E19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streed CG Jr, Hedian HF, Bertram A, & Sisson SD (2019). Assessment of Internal Medicine Resident Preparedness to Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning Patients. Journal of general internal medicine, 34(6), 893–898. 10.1007/s11606-019-04855-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streed CG Jr, Lunn MR, Siegel J, & Obedin-Maliver J (2021b). Meeting the Patient Care, Education, and Research Missions: Academic Medical Centers Must Comprehensively Address Sexual and Gender Minority Health. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 96(6), 822–827. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufomata E, Eckstrand K, Hasley P, Jeong K, Rubio D, & Spagnoletti C (2018). Comprehensive Internal Medicine Residency Curriculum on Primary Care of Patients Who Identify as LGBT. LGBT Health, 5(6), 375–380. 10.1089/LGBT.2017.0173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenti K, Jen S, Parajuli J, Arbogast A, Jacobsen A, & Kunkel S (2020). Experiences of Palliative and End-of-Life Care among Older LGBTQ Women: A Review of Current Literature. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(11), 1532–1539. 10.1089/JPM.2019.0639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa J, Medina L, & Armstrong DM (2020). Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. US Census Bureau. Retrieved from www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popproj [Google Scholar]

- Wahlert L, & Fiester A (2012). Mediation and surrogate decision-making for LGBTQ families in the absence of an advance directive : comment on “Ethical challenges in end-of-life care for GLBTI individuals” by Colleen Cartwright. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 9(3), 365–367. 10.1007/S11673-012-9387-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson DB (2019). Building Trust in the LGBTQ Community. ABIM Foundation. https://abimfoundation.org/blog-post/building-trust-in-the-lgbtq-community [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

In accordance with IRB stipulations, data will not be posted online but can be made available at request.