Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cell is an essential cytotoxic lymphocyte in our innate immunity. Activation of NK cells is of paramount importance in defending against pathogens, suppressing autoantibody production and regulating other immune cells. Common gamma chain (γc) cytokines, including IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21, are defined as essential regulators for NK cell homeostasis and development. However, it is inconclusive whether γc cytokine-driven NK cell activation plays a protective or pathogenic role in the development of autoimmunity. In this study, we investigate and correlate the differential effects of γc cytokines in NK cell expansion and activation. IL-2 and IL-15 are mainly responsible for NK cell activation, while IL-21 preferentially stimulates NK cell proliferation. Blockade of Janus tyrosine kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling pathway by either JAK inhibitors or antibodies targeting γc receptor subunits reverses the γc cytokine-induced NK cell activation, leading to suppression of its autoimmunity-like phenotype in vitro. These results underline the mechanisms of how γc cytokines trigger autoimmune phenotype in NK cells as a potential target to autoimmune diseases.

1. Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cell refers to a type of immune cells that play an important role in innate responses to viral infections and cancer [1–3]. In the innate immune system, NK cell does not require prior sensitization for the recognition and killing of tumor cells of various histologic origins and virally infected cells [4]. Two main subpopulations of NK cells are classified by the surface expression of cluster of differentiation (CD)56 and CD16, termed the CD56brightCD16− and CD56dimCD16+ NK cells, which differ in terms of phenotype, function, and tissue localization [5, 6]. CD56brightCD16− NK cells are primarily found in lymphoid tissues with lower cytotoxic activity, but are efficient producers of cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and cytolytic proteins such as perforin upon stimulation by proinflammatory cytokines like IL-2 and IL-12 [7–9]. In contrast, CD56dimCD16+ NK cells are predominantly present in peripheral blood with high cytolytic activity, but are less responsive to cytokine stimulation than the CD56brightCD16− population [5].

The development, homeostasis, and regulation of functional activities of NK cells are predominantly modulated by a cytokine family, namely the common gamma chain (γc or CD132) cytokines [10, 11]. The γc chain is a 40-kDa type I transmembrane glycoprotein that acts as a common receptor subunit for the cytokine family that comprises of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21 [12]. Upon heterodimerization with a proprietary cytokine receptor (IL-2Rβ, IL-4Rα, IL-7Rα, IL9Rα, or IL-21R), which possesses Janus tyrosine kinase (JAK)-1 protein, the JAK3 protein associated with γc receptor is activated to transduce downstream signals through JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway for triggering immune responses against pathogens [13, 14].

Among six γc cytokines, IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21 play indispensable roles in NK cell development and immune functioning. IL-2 and IL-15 share similar functional properties that they both utilize the same receptor components IL-2Rβ and γc to transduce signaling pathways [15]. Both cytokines play important roles in the activation, proliferation, and cytotoxicity of NK cell. Also, these cytokines can convert NK cells from resting to highly cytolytic phenotype with enhanced secretion of perforin and granzymes [16]; they also promote the generation of IFN-γ that further enhances the activities of NK cell and macrophage [17–19]. Furthermore, both cytokines have been shown to induce expression of NKG2D (activating) and CD158a/CD158b (inhibitory) receptors on NK cell lymphocyte subsets originating from regional lymph nodes [20]. A more recently discovered γc cytokine, IL-21, is a remarkable regulator of NK cell function. IL-21 is involved in the upregulation of CD16 expression that potentiates the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity and costimulation of perforin, granzymes, and IFN-γ secretion [10]. Furthermore, costimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with IL-2 and IL-21 also triggers proliferation of CD56bright NK cells and significantly upregulates the cytotoxicity of CD56dim NK cells, when compared to IL-2 or IL-21 stimulated groups [21].

Autoimmune disease is distinguished by the loss of self-tolerance and presence of autoreactive immune cells in the body. Indeed, several mechanisms have been proposed to elucidate the detrimental role of NK cells in the progression of diseases, including the ability of recognizing stress-induced ligands on self-tissue cells during infection [22], secretion of proinflammatory cytokines to promote tissue damage [23], and the imbalance between NK activating and inhibitory receptors that promote the generation of autoreactive T cells [24]. For example, increased numbers of NK cell have been observed in clinical samples from patients with Crohn's disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [25, 26]. However, evidences have been suggested for NK cells to play protective roles to limit the severity of immunity through the regulation of T and dendritic cells in tissue repair, inhibition of autoreactive T-cell activity, and induced differentiation of regulatory T cells [27]. Although γc cytokines are correlated with the severity of multiple autoimmune diseases (vitiligo, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, psoriasis, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis vulgaris, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren's syndrome, and type 1 diabetes) in humans [28–50], their effects on NK cell homeostasis during autoimmune diseases remain unclear.

In the current study, IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21 were found to differentially modulate NK cell expansion and activation phenotype in PBMC culture. Through the blockade of JAK/STAT pathway by JAK inhibitors, NK cell expansion and activation were completely abolished. Interestingly, direct blockade of downstream JAK3 activity with anti-γc antibody could suppress γc cytokine-induced NK cell activation but maintains immunity against tumor cells, suggesting that antibody might offer a safer strategy to treat NK cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. Using the isolated primary NK cell as a model, we further demonstrate that long-term γc cytokine-stimulated NK cells exhibit autoimmune phenotype and cytotoxicity against healthy mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and the application of anti-γc antibody is able to rescue MSCs. The current study indicates that application of anti-γc antibody might serve as a better strategy to target NK cell-associated autoimmune diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Reagents

PBMCs (#10HU-003-CR100M) were purchased from iXCells Biotechnologies (San Diego, California, USA). Myelogenous leukemia cell line K562 (CCL-243™) was obtained from ATCC, and bone marrow MSCs (#A15652) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

PBMCs were cultured in complete ATCC-modified RPMI 1640 Medium (#A1049101), supplemented with 1x penicillin/streptomycin (#15140122) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (A3160801). Cells were cultured at 2 × 106 cells/ml. K562 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 Medium (#11875135), supplemented with antibiotics and 10% FBS, at 2 × 105 cells/ml. Bone marrow MSCs were cultured in MesenPRO RS™ Medium (#12746012, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 5 × 103 cells/cm2. All cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere. All media and reagents for cell culture were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The sources of cytokines, inhibitors, and neutralizing antibodies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reagent and antibody lists.

| Category | Item | Company | Catalog number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | Human IL-2 | Sino Biological | 11848-HNAH1-E |

| Human IL-4 | Sino Biological | 11846-HNAE | |

| Human IL-7 | Sino Biological | 11821-HNAE | |

| Human IL-9 | Sino Biological | 11844-H08B | |

| Human IL-15 | Sino Biological | 10360-HNCE | |

| Human IL-21 | Sino Biological | 10584-HNAE | |

| Human premium grade IL-2 | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-097-748 | |

|

| |||

| Inhibitor | Tofacitinib (JAK1/JAK3) | Tocris (Abingdon, UK) | 4556 |

| Ruxolitinib (JAK1/JAK2) | Tocris | 7064 | |

| Ritlecitinib (JAK3) | Tocris | 6506 | |

|

| |||

| Neutralizing antibodies | Antihuman γc antibody | R&D System, Minneapolis, USA | MAB2842 |

| Antihuman CD25 antibody | R&D System | MAB223 | |

| Antihuman CD122 antibody | R&D System | MAB224 | |

| Mouse IgG2b control | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 02-6300 | |

|

| |||

| Flow cytometry antibodies | Antihuman CD3 antibody | BioLegend | 317314 |

| Antihuman CD56 antibody | BioLegend | 392414 | |

| Antihuman NKG2A antibody | BioLegend | 375104 | |

| Antihuman NKG2D antibody | BioLegend | 320808 | |

| Antihuman FasL antibody | BioLegend | 306407 | |

| Antihuman KIR antibody | BioLegend | 339504 | |

| Antihuman NKp44 antibody | BioLegend | 325110 | |

| Antihuman NKp46 antibody | BioLegend | 331922 | |

| Antihuman granzyme B antibody | BioLegend | 372206 | |

| Antihuman perforin antibody | BioLegend | 353312 | |

| Antihuman IFN-γ antibody | BioLegend | 502512 | |

|

| |||

| WB antibodies | Anti-STAT3 | CST | 9139 |

| Anti-p-STAT3 | CST | 9145 | |

| Anti-STAT5 | CST | 94205 | |

| Anti-p-STAT5 | CST | 9359 | |

| Anti-STAT6 | CST | 5397 | |

| Anti-p-STAT6 | CST | 56554 | |

| Antitubulin | Sino Biological | 100109-MM05T | |

| HRP goat antimouse IgG | CST | 7076 | |

| HRP goat antirabbit IgG | CST | 7074 | |

2.2. WST-8 Proliferative Assay

One hundred thousand PBMC cells were seeded into each 96-well plate before treatment. After 3-day cytokine and drug incubation, 10 μl WST-8 reagent (ab228554, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added to each well and optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm between 4 and 8 hr using Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each group was tested in duplicate.

2.3. Primary NK Cells Isolation and Expansion

NK cells were isolated from PBMC using Human NK Cell Isolation Kit II (#130-092-657, Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Purified NK cells were resuspended in fresh complete NK MACS medium (#130-114-429, Miltenyi Biotec) with 50 ng/ml premium grade IL-2. After 5-day priming with IL-2, cells were expanded with 50 ng/ml premium grade IL-2 and 25 ng/ml IL-21 up to 3 weeks. Percentage of NK cell population was determined by flow cytometry to confirm the NK cell enrichment and expansion following cytokine treatment.

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analyses of PBMCs and Purified NK Cells

Sources of antibodies are summarized in Table 1. Cytokine-stimulated PBMCs or purified NK cells were washed with FACS wash buffer (2% FBS in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) and then surface stained with CD3 antibody and CD56 antibody to label the CD3-CD56+ NK cell population. Cells were then incubated with antibodies targeting NK surface markers for 30 min at RT.

For intracellular staining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (#158127, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) at 4°C for 10 min after surface staining. After washing and incubating in 0.1% Triton-X in PBS at 37°C for 10 min, cells were labeled with antibodies targeting intracellular markers at 37°C for 30 min. Percentage of positively labeled cells was identified by BD FACS Lyric™ Clinical Cell Analyzer (BD Biosciences, New Jersey, USA) as previously described [51]. Unstained control without antibody incubation was used for gating.

2.5. Western Blot (WB)

Antibodies for WB were purchased from CST (Danvers, Massachusetts, USA) or Sino Biological, as summarized in Table 1. Total proteins were extracted from the PBMC in RIPA lysis buffer (#20-188, Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) with inhibitor cocktail (#78440, Thermo Fisher Scientific) after 15 min cytokine incubation. Protein concentration was measured by Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (#23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then diluted in NuPAGE™ LDS Sample Buffer (#NP0007, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol (#1610710, Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). After boiled at 95°C for 10 min, protein lysates (20–40 mg/lane) were separated through electrophoresis and blotted on the nitrocellulose membrane (GE10600001, Sigma-Aldrich). Membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk (#1706404, Bio-Rad) and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Next day, membrane was washed with PBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 60 min at RT. Protein bands were visualized using ECL substrate kit (#34580, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

2.6. Cytotoxicity Assays to K562 and MSC

For cell-to-cell cytotoxicity assay, PBMCs or overnight starved purified NK cells were pretreated γc antibody for 1 hr, followed by single cytokine (IL-2/IL-15/IL-21) or cytokine cocktail stimulation for 3 days. K562 and MSCs (target cells) were counted and 1 × 106 cells were labeled with 100 µM of CFSE (#423801, BioLegend) for 10 min at 37°C. Labeled target cells were washed and resuspended in complete ATCC-modified RPMI medium. Prestimulated PBMCs or purified NK cells (effector cells) were introduced to target cells in different E : T ratios. The cell mixture was harvested after 4 hr incubation, washed, and centrifuged. Cells were then resuspended in 50 ng/ml propidium iodide (PI) (#P1304MP, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed with FACS analysis. CFSE- and PI-labeled target cell populations were quantified to determine cytotoxicity levels of effector cells.

For soluble factor secretion cytotoxicity assay, PBMCs or overnight starved isolated NK cells were pretreated with γc antibody and stimulated with single cytokine or cytokine cocktail as same as the condition of cell-to-cell cytotoxicity assay above. Supernatant was harvested from PBMC and NK cell culture after stimulation for 3 days. K562 was counted and 1 × 106 K562 cells were incubated with the supernatant in 1 : 1 ratio for 16 hr at 37°C. Treated K562 cells were washed, centrifuged, and resuspended in 50 ng/ml PI. The labeled cells were analyzed with FACS analysis. PI-labeled K562 cell population was investigated to determine soluble factor-mediated cytotoxicity.

2.7. ELISA

ELISA assay is the golden standard for determining cytokine level in the clinical and laboratory samples [52]. After cytokine stimulation, PBMC and NK cell culture supernatant was harvested and ELISA assays were performed according to manufacturer protocols. DuoSet ELISA measuring human granzyme A (#DY2905-05), granzyme B (#DY2906-05), IFN-γ (#DY285B), IL-4 (#DY204-05), IL-5 (#DY205), IL-6 (#DY206), IL-10 (#DY217B05), IL-13 (#DY213), and IL-22 (#DY782-05) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Human perforin-coated ELISA (#BMS2306) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

2.8. Statistical Analyses

The signal intensities of protein bands in WB were determined by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Data from flow cytometry were quantified by FlowJo (version 10, BD, Ashland, OR, USA). Statistical analyses were conducted by Prism (version 8, GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). p < 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant between groups.

3. Results

3.1. JAK/STAT Pathways Were Triggered by IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21 in PBMCs

Biological effect of γc cytokines on JAK/STAT pathway in PBMC was investigated through WB analysis. Results showed that each γc cytokine except IL-9 activated one major STAT protein in the culture (Figure 1(a)). STAT phosphorylation was relatively weak in IL-9-treated PBMCs and quantification confirmed the results (Figure 1(b)–1(d)). Proliferation of PBMC was then measured by WST-8 assay after 3-day cytokine treatment. IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 all promoted PBMC proliferation, and the strongest effect was observed in IL-15 stimulation (Figure 1(e)). Moreover, IL-2 and IL-7 cotreatment could further promote PBMC proliferation in the culture (Figure 1(e)), suggesting the synergistic effect of γc cytokines in PBMC proliferation and STAT5 phosphorylation as a potential indicator for measuring proliferative activity in PBMC culture.

Figure 1.

γc cytokines activated JAK/STAT pathways and modulated NK homeostasis in PBMC culture. (a) PBMCs were treated with γc cytokines (50 ng/ml) for 15 min and harvested for western blot analysis. All cytokines, except IL-9, induced phosphorylation of STAT proteins. (b–d) Quantification demonstrated that each cytokine (except IL-9) could stimulate one major STAT phosphorylation in PBMC culture. (e) WST-8 proliferation assay indicated that 3-day treatment of IL-15, IL-2/IL-7, and IL-2/IL-15 (50 ng/ml for each cytokine) significantly induced proliferation of PBMCs. (f) Representative graphs of CD3−CD56+ (CD56bright and CD56dim) expressing cells demonstrated 3-day treatment of γc cytokine (IL-2 : 20, IL-15 : 20, and IL-21 : 25 ng/ml) induced NK cells expansion as consistent to WST-8 assay. (g) Quantification demonstrated that IL-21, IL-2/21, and IL-15/21 significantly induced NK cell expansion in PBMC culture. Representative images of 3-day treatment of IL-2 (20 ng/ml), IL-15 (20 ng/ml), and IL-2/15 (20 ng/ml) induced (h) NKG2A+ and (j) FasL+ expression in NK cells. IL-15 and IL-2/IL-15 significantly induced (i) NKG2A and (k) FasL expression, in which IL-2/IL-15 demonstrated synergetic effects in FasL expression. For above experiments, PBMCs were treated with corresponding cytokines with indicated time. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to controls using Dunnett's multiple comparisons test following one-way ANOVA. #p < 0.05 was compared to indicated group by Student's t-test. N = 3 for (a–e), N = 4 for (f–k).

3.2. IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21 Differentially Modulated NK Cell Expansion and Phenotype

Next, expansion of immune cell type after 3-day cytokine treatment was investigated through flow cytometry analyses. IL-2 and IL-7 treatment could induce T-cell expansion (data not shown), while IL-21 could increase NK cell population (CD3-CD56+) significantly (Figure 1(f)). Moreover, combined treatment of IL-2/IL-15 showed a trend to synergistically increase NK cell population in PBMC culture (Figure 1(g)). The effects of three γc cytokines on shaping NK cell phenotype were then studied by surface receptor expression analyses. CD94/NKG2A is regarded as an inhibitory receptor for immune checkpoint in NK cells. NKG2A recognizes HLA class I and E on normal cells to inhibit NK cell activity, thus suppressing NK cell-mediated autoimmunity. Although NKG2A+ NK cells function to identify self and nonself-cells in the body, uncontrolled expression of NKG2A is also an indication of NK cell exhaustion [53, 54]. FasL is a type II transmembrane protein that specifically binds to FasL receptors expressing on target cells to induce cytotoxicity [55, 56]. Data indicated that IL-15 could induce NKG2A expression (Figures 1(h) and 1(i)), while IL-15 alone and IL-2/IL-15 combined treatment contributed to FasL upregulation on NK cells (Figures 1(j) and 1(k)), suggesting these two cytokines may play alternative roles in modulating and activating NK cell in a healthy PBMC culture.

3.3. IL-2 and IL-15 Contributed to NK Cell Activation in the PBMC Culture

Secretion of perforin, IFN-γ, and granzymes are classified as the markers for NK cell activation during infection, tumor development, and autoimmunity progression [7, 57–60]. Thus, we studied whether γc cytokines can modulate the production of these soluble factors to evaluate the NK cell activation status. Similar to previous results, IL-2 and IL-15 significantly induced secretion of IL-6, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzymes A/B, in which IL-2/IL-15 cotreatment showed synergistic effect on granzyme B and IFN-γ production by PBMC as analyzed by ELISA (Figure 2(a)–2(e)). Although IL-21 alone did not induce secretion of all studied cytotoxic soluble factors, IL-2/IL-21 showed synergistic effect on granzyme B secretion from PBMC culture (Figure 2(e)). To confirm if NK cell is one of the main cell types for soluble factor secretion, intracellular levels of those factors were measured by FACS analysis. Consistent to ELISA results, individual IL-2 and IL-15 treatment could trigger intracellular IFN-γ and granzyme B expression in the CD3-CD56+ NK cells (Figures 2(f) and 2(g)), suggesting that NK cell was one of the cell types responsible for granzyme B and IFN-γ secretion. To further confirm whether two cytokines could induce activation of multiple NK cell subpopulation, cytokines involved in shaping natural killer type (NK)1/NK2/NK3/NKr cell phenotypes [61, 62] were measured. ELISA results demonstrated that in PBMCs culture, NK2 (IL-13), NK3 (transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)), and NKr (IL-10) cytokines were only increased in IL-15/IL-21-treated groups only (Supplementary 1, data not shown). By calculating the NK1 (IFNγ-producing)/NK2 ratio through dividing IFN-γ and IL-6 level by IL-5 level for each individual group, it was identified that the presence of IL-15 or IL-2/IL-21 could predominantly trigger NK1 phenotype in the PBMC culture (Supplementary 1).

Figure 2.

IL-2 and IL-15 contributed to NK cell activation and K562 cytotoxicity. Supernatants were harvested for ELISA, while PBMC cells were harvested for FACS analysis after 3-day cytokine (IL-2 : 20, IL-15 : 20, and IL-21 : 25 ng/ml) incubation. Differential or combinatorial treatment of IL-2- and IL-15-induced production of (a) IFN-γ, (b) IL-6, (c) perforin, (d) granzyme A, and (e) granzyme B, respectively. Representative images of intracellular (f) IFN-γ and (g) granzyme B in gated NK cells after 3-day cytokine challenges. (h) Schematic diagram for NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay with FACS analysis. A 3-day cytokines (IL-2 : 20, IL-15 : 20, and IL-21 : 25 ng/ml) stimulated PBMCs or supernatants were introduced to K562 for studying cell-mediated or soluble factor-mediated cytotoxicity assay, respectively. (i) All studied groups, except IL-21, enhanced K562 lysis significantly compared to control. (j) In E : T ratio of 25 : 1, IL-15, IL-2/IL-15, IL-2/IL-21, and IL-15/IL-21 treated PBMCs significantly lysed K562 lysis cells. (k) Supernatants harvested from IL-15 and IL-2/IL-15 treated PBMCs significantly lysed K562 lysis cells. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to medium or control groups using Dunnett's multiple comparisons test following one-way ANOVA for (a–e) and (j and k). ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to control using Tukey's multiple comparisons test following two-way ANOVA for (i). ##p < 0.01 was compared to indicated group by Student's t-test. N = 3 for all groups.

3.4. Prestimulated NK Cells Are Responsible for K562 Lysis

The upregulation of activating receptors and intracellular expression of cytotoxic factors in NK cells potentially led to cytotoxicity on target cells. This phenomenon was studied by determining K562 lysis (PI + cells) either coculture with γc cytokine-activated PBMCs or supernatant harvested from activated PBMC cultures (Figure 2(h)). For cell-mediated cytotoxicity, the presence of IL-15 in all studied PBMC groups triggered significant cytotoxicity against K562 at all studied E : T ratios and the optimal ratio was 25 : 1 (Figures 2(i) and 2(j)). Consistent to cell-mediated cytotoxicity, supernatant harvested from PBMCs with IL-15 or IL-2/IL-15 treatment also led to significant K562 lysis (Figure 2(k)). These results further confirmed that IL-2 and IL-15 play vital roles in promoting NK cell activation and cytotoxicity, while IL-21 preferentially promotes NK cell expansion in the PBMC culture.

3.5. JAK/STAT Inhibitor Totally Abolished NK Expansion and Activation

IL-2 and IL-15 could stimulate several downstream signaling pathways for NK proliferation, activation, and immune functions [63–67]. Among these pathways, JAK/STAT pathway is important for NK cell expansion and activation [68]. This phenomenon was explored using three JAK inhibitors in the PBMC culture according to our previous data [69]. All studied JAK inhibitors could significantly suppress immune cell expansion in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15 dose dependently (Figure 3(a)–3(f)). Low-dose (1 µM) tofacitinib was selected for following experiments to fit with the γc downstream pathway (JAK1/JAK3).

Figure 3.

JAK/STAT inhibitors completely attenuated γc cytokines effects on NK cells expansion, activation, and cytotoxicity. PBMCs were pretreated by JAK inhibitors for 1 hr, followed by γc cytokines (50 ng/ml) stimulation for 3 days. Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2), tofacitinib (JAK3), and ritlecitinib (JAK3) inhibited (a–c) IL-2- and (d–f) IL-15-induced proliferation in PBMC culture in dose-dependent manner, respectively. (g and h) Representative images of FACS analysis demonstrating tofacitinib suppressed γc cytokines (50 ng/ml) induced CD3−CD56+ NK cells and FasL+ NK cell population and (i and j) quantification confirmed the results. (k and l) Representative images of FACS analysis showing tofacitinib suppressed IL-2 or IL-15 induced cytotoxicity against K562 and quantification confirmed the results. (m–o) Tofacitinib also eradicated IL-2- and IL-15-induced secretion of granzyme A, Granzyme B and IFN-γ secretion in the culture. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to control or DMSO control using Dunnett's multiple comparisons test following one-way ANOVA. ###p < 0.001 was compared to control by Student's t-test. N = 3 for all groups.

Flow cytometry analyses confirmed that blockade of JAK/STAT pathway by tofacitinib attenuated IL-2- and IL-15-induced expansion of NK cells in the PBMC culture (Figures 3(g) and 3(i)), as well as complete suppression of FasL expression on NK cells (Figures 3(h) and 3(j)). Functionally, tofacitinib totally abolished cell-mediated cytotoxicity against K562 tumor cells (Figures 3(k) and 3(l)) and release of cytotoxic factors (Figure 3(m)–3(o)). Altogether, these data suggested that JAK/STAT pathway is essential for NK cell expansion and activation during IL-2 or IL-15 stimulation and blockade of JAK/STAT pathway potentially suppresses acute NK cell activation.

3.6. Blocking γc Receptor Resulted in Attenuation of NK Cell Activation Via Suppressing Cytotoxic Factors Secretion

As tofacitinib preferentially suppressed JAK1 and JAK3 activation in the cells and numerous side effects were observed after JAK1 inhibition in clinical trials [70], we hypothesize if specific blockade of JAK1 and JAK3 activation by neutralizing antibodies against respective receptors could provide comparable efficacy to suppress NK cell activation in our system. Through treating preactivated PBMC cultures with anti-CD25 or anti-CD122 neutralizing antibodies, the data demonstrated that NK cell activation could be attenuated, while NK cell population and cytotoxicity against tumor cells could be retained (Supplementary 2 and 3), suggesting that antibody treatment might be a safer strategy for JAK inhibition.

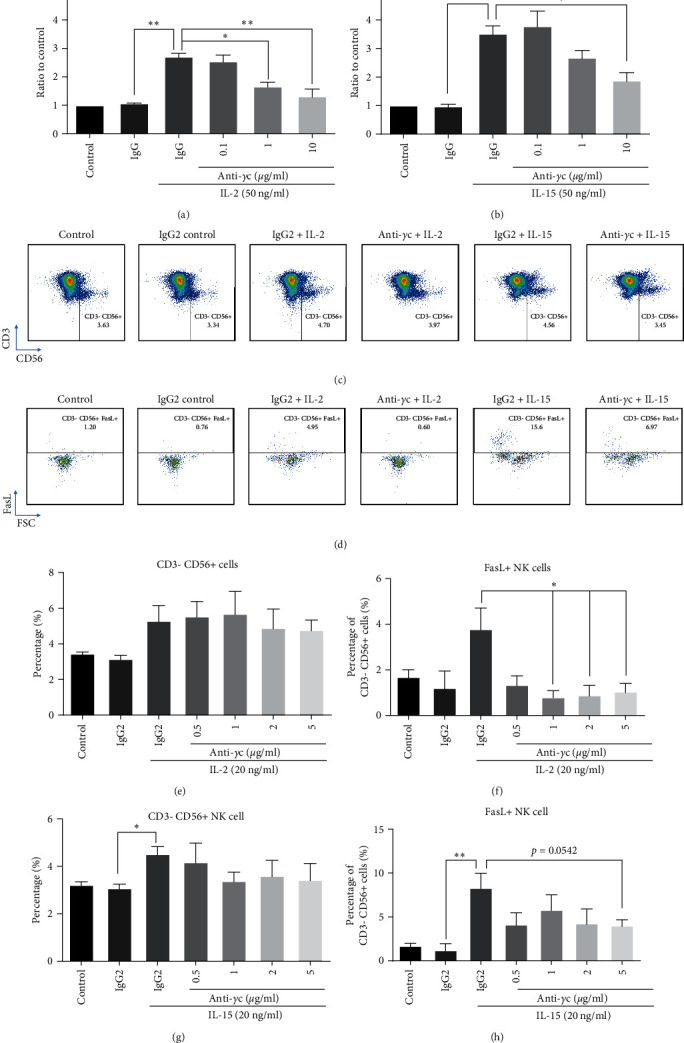

Next, the effect of specific JAK3 inhibition by anti-γc antibody was compared to anti-CD25 and anti-CD122 antibodies in restoring normal NK cell phenotype in the presence of cytokine stimulation. In concordance with previous data, anti-γc antibody could significantly reduce PBMC proliferation (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)) and NK cell activation (FasL expression) in the presence of IL-2 or IL-15 (Figures 4(d), 4(f), and 4(h)) but maintained the NK population (Figures 4(c), 4(e), and 4(g)) in PBMC culture. In contrast, anti-γc antibody could suppress both IL-2 triggered cytotoxicity against tumor cells (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)) and soluble factor release (Figure 5(d)–5(i)) when compared to anti-CD25 treated groups. The inhibitory effects of IL-15-induced soluble factor secretion were comparable between anti-γc and anti-CD122 antibodies (Figure 5(j)–5(o) and Supplementary 4), while the antitumor effect was preserved (Figure 5(c)). These results clearly indicate the potential uses of anti-γc antibody to treat NK cell-mediated autoimmune diseases.

Figure 4.

Anti-γc antibody attenuated NK activation only while maintained NK cell survival. PBMCs were pretreated by anti-γc (5 µg/ml) for 1 hr, followed by IL-2 (50 ng/ml) and IL-15 (50 ng/ml) stimulation for 3 days. (a and b) Anti-γc attenuated IL-2- and IL-15-induced proliferation on PBMC culture. Representative images of FACS analysis showing that anti-γc suppressed IL-2- and IL-15-induced (c) CD3−CD56+ NK cells and (d) FasL+ NK cell population. (e and g) Quantification demonstrated that anti-γc did not alter γc cytokines-induced CD3CD56+ NK cell population, but significantly suppressed (f) IL-2 and (h) IL-15 induced FasL+ NK cell population. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to isotype control by Student's t-test, N = 4. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to isotype control with cytokine treatment using Dunnett's multiple comparisons test following one-way ANOVA. N = 4 for all groups.

Figure 5.

Anti-γc antibody suppressed secretion of cytotoxic factors but maintained NK cells antitumor activities. (a) Representative images of FACS analysis showing anti-γc antibody suppressed cytokines-induced cytotoxicity against K562. Quantification demonstrated anti-γc antibody suppressed (b) IL-2 induced cytotoxicity against K562 significantly, but not for (c) IL-15. (d–m) Anti-γc attenuated IL-2-induced secretion of granzyme a and granzyme B significantly at different doses, while only inhibiting IL-15-induced secretion at 5 µg/ml. (h–o) Anti-γc only attenuated IL-2- and IL-15-induced secretion of IFN-γ at 5 µg/ml only. Inhibitory ratio is calculated via dividing values obtained from antibody treated groups over values from isotype controls in the presence of either IL-2 or IL-15. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to isotype control by Student's t-test, N = 4. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 were compared to isotype control with cytokine treatment using Dunnett's multiple comparisons test following one-way ANOVA. N = 4 for all groups.

3.7. γc Cytokines Could Directly Activate Primary NK Cells Independent of Other Immune Cell Types

To conclude whether γc cytokine could directly induce NK cell activation independent of other immune cell types, primary NK cells were purified, primed with IL-2, and expanded with the combined treatment of IL-2 and IL-21. After 14-day culture, T cells were completely depleted and NK cells were enriched to 90% in the culture (Figures 6(a) and 6(b)), with maintained cytotoxicity against K562 tumor following 1 day cytokine treatment (Figure 6(c)). NK cells were starved overnight and then incubated with a combination of γc cytokines for 3 days. Results indicated that IL-2 or IL-15 but not IL-21 could induce expression of activating receptors, including FasL, TRAIL, and NKp46, on primary NK cell surface (Figure 6(d)). Interestingly, either IL-2/IL-15 or IL-2/IL-21 cotreatment groups showed higher NKp46 expression when compared to single cytokine-treated groups. The expression of inhibitory NKG2A and KIR was gently induced in all treatment groups except IL-2/IL-21 group. No expression of NK exhaustion marker TIM-3 was detected in any groups. To study the autoimmune phenotype of stimulated NK cells, activating/inhibitory receptor ratio was calculated by NKp46/KIR levels. The ratio clearly showed that primary NK cells were shifted to autoimmune phenotype in the presence of either IL-2/IL-15 or IL-2/IL-21 in the culture (Figure 6(e)).

Figure 6.

Long-term γc cytokine treatment shaped autoimmune phenotype in purified NK cells. (a and b) Percentage of T cells and NK cells after expansion with IL-2 and IL-21. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 as compared to controls using student t-test, N = 2 for all groups. (c) Purified NK cell cytotoxicity assay to K562 cell line after priming and expansion with differential γc cytokines for 14 days. (d) Representative histogram of FACS analysis showing differential levels of activating and inhibitory receptors after 3-day γc cytokine (IL-2 : 50, IL-15 : 50, IL-21 : 25 ng/ml) treatment. (e) IL-2/IL-15 and IL-2/IL-21 combinatorial treatment significantly upregulated activating to inhibitory receptor ratio (NKp46/KIR). ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 as compared to controls using Dunnett's multiple comparisons test following one-way ANOVA, N = 3 for all groups.

3.8. Suppression of γc Receptor Pathway-Attenuated NK Autoimmunity

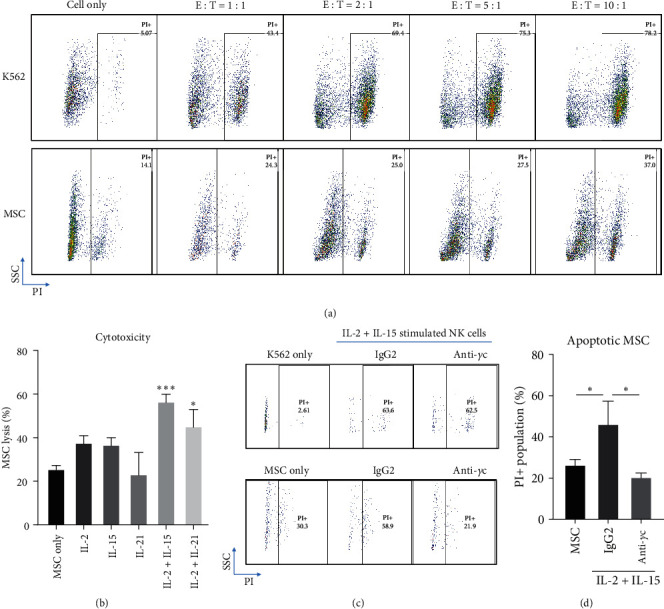

As blockade of γc cytokine pathway in T cells is proposed to be one of the ways to reverse development of autoimmunity [8, 71], the similar phenomenon was also studied in purified NK cells. Cultured NK cells acquired exaggerated cytotoxicity against K562 tumor cells, with development of autoimmunity against healthy MSCs simultaneously in the presence of IL-2 and IL-21 (Figure 7(a)). To further demonstrate this phenomenon, NK cells were starved overnight and challenged with different combination of γc cytokines for 3 days. Results indicated that IL-2/IL-15 and IL-2/IL-21 pretreated groups showed significant autoimmunity against MSCs, which are consistent to the expression of activating receptors (Figure 7(b)) and intracellular levels of cytotoxic soluble factors (Supplementary 4) in the NK cell culture. More importantly, the presence of anti-γc antibody could rescue MSCs during coculture with IL-2/IL-15 prestimulated NK cells (Figures 7(c) and 7(d)), suggesting that suppression of γc activity on NK cells might be a potential way to treat autoimmune diseases.

Figure 7.

Anti-γc reversed cytokines-induced autoimmune phenotype in purified NK cells. Purified NK cells were long-term stimulated with IL-2 + IL-21 (IL-2 : 50, IL-21 : 25 ng/ml) for 3 weeks, followed by cytotoxicity assay. (a) Representative images of FACS analysis demonstrating long-term stimulated NK cells with γc cytokines exhibited cytotoxicity against K562 and MSC. Optimal cytotoxicity to MSC was obtained at E : T ratio 10 : 1. (b) Quantification demonstrated 3-day IL-2/IL-15 and IL-2/IL-21 (IL-2 : 50, IL-15 : 50, IL-21 : 25 ng/ml) combinatorial treatment promoted MSC lysis. (c) Representative FACS images showing anti-γc reversed IL2-/IL-15-induced cytotoxicity to MSCs. (d) Quantification confirmed this result. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗∗p < 0.01 were compared to control using Dunnett's multiple comparisons test following one-way ANOVA. N = 3 for all groups.

4. Discussion

The present data support the phenomenon that γc receptor signaling can modulate NK cell functions and phenotypes. Although IL-2 and IL-15 bind to individual receptor subunit, respectively, they use the common γc and IL-2Rβ chains to trigger tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT5 via JAK1/JAK3 pathways [72]. Despite the similarities in the signaling cascades after receptor trimerization, IL-2 and IL-15 are responsible to trigger distinctive functions on several immune cells due to the differences in IL-2Rα and IL15Rα composition on self- and neighboring cell surfaces [73]. IL-2 is responsible to expand CD4+ helper T cells and regulatory T cells, while IL-15 could support the development of NK cells and central memory T cells [74]. For instance, IL-2 and lL15 can induce and both activate NK cell but IL-15 is more potent to trigger its survival and cytolytic activity [75]. Furthermore, IL-2 activated NK cells that undergo apoptosis upon initial interaction with endothelial and tumor cells, while IL-15 maintains NK cell survival under the same condition [76]. Although short-term IL-15 treatment could support NK cell function and survival in the culture, continuous IL-15 treatment eventually leads to decreased viability, functional impairment, and NK cell exhaustion in PBMC culture and in vivo xenogeneic model [77]. As a more recently discovered γc cytokine, IL-21 is found to modulate NK progenitor cell development and proliferation [78]. Also, IL-21 could directly trigger NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity against breast cancer cells [79]. Therefore, it is important to dissect the overlapping and distinct relationship of a combination of γc cytokines in NK cell homeostasis and autoimmunity. Currently, our in vitro data are consistent to previous findings that IL-2 and IL-15 specifically induce NK activation and cytotoxicity against target cells, while IL-21 preferably stimulates NK proliferation [80–82].

Among all studied cytokines, IL-15 acts as a more potent mediator to trigger NK cell activation and cytotoxicity as previously shown [75, 83]. These results might be explained by different expression of surface receptors on NK cells. IL-2 is responsible to upregulate the expression of activating NKG2D and DNAM-1, which recognize the stress-induced ligands on target cells [84]. IL-15 is more effective in upregulating the expression of NKp46 and NKp30, which are involved in the recognition and killing of tumor- and virus-infected cells; IL-15 also increases the CD69 expression, which is an early activation marker on T and NK cells [85, 86]. More importantly, synergistic effects in NK activation were shown in IL-2/IL-15 and IL-15/IL-21 cotreatments as previously reported [80–82, 87–89], demonstrating the high innate immune efficiency of NK cells responding to multiple stimulus.

NK cells can be characterized into NK1 and NK2 subpopulation according to cell surface markers and cytokine secretion profile as shown in T-helper 1 and 2 phenotypes in T cells. NK1 cell is classified by CD56dim/CD95high/perforinhigh phenotype [90, 91] and actively produces IFN-γ and TNF-α; NK2 cell refers to CD56bright/CD122high/CD27high/CD69high population [91] and secrets IL-5 and IL-13 [61, 92]; NK3 cell might express high level of CD127 and secretes TGF-β [61, 91] and NKr1 cell is reported to secrete IL-10 to promote immune regulation [61]. In the current study, IL-2 and IL-15 stimulation was identified to preferentially shift NK cell from NK0 (inactivated status) to a dominant NK1 phenotype (Figures 1 and 2 and Supplementary 1), which could potentially lead to long-term inflammation and development of autoimmunity in the culture [93]. On the other hand, IL-15/IL-21 cotreatment led to a mixed NK1/NKr1 phenotype, which might potentially explain IL-21 to exhibit immunosuppressive action on NK cell activation [94].

As aforementioned, γc cytokines share common JAK/STAT pathways for signal transduction and immune responses in most immune cells. It is hypothesized that suppression of JAK/STAT pathway through blocking JAK protein or upstream γc receptor subunits can potentially attenuate γc cytokine-driven NK cell homeostasis as a strategy to tackle NK cell-mediated autoimmune or inflammatory diseases. Administration of JAK1/3 inhibitor tofacitinib, and antibodies targeting receptor subunit or γc receptor, could suppress NK cell activities after IL-2 and IL-15 challenges (Figures 4 and 5). However, the normal immune functions against tumor cells by NK cells and cytotoxic T cells were impaired after tofacitinib treatment and so increased risk of cancer is usually observed after JAK inhibitor treatment [95, 96]. Alternatively, neutralization of CD25, CD122, or γc receptor by respective antibodies could still block γc cytokine-induced NK cell activity, while maintained IL-15 induced antitumor activity (Supplementary 1 and 2 and Figures 4 and 5). A possible explanation for this observation is in accordance with other groups that complete loss of JAK1 activity in mouse NK cells lead to innate immune deficiency and reduced number of NK cells [97, 98]. Also, loss of JAK1 abrogates all downstream signaling pathways, while loss of JAK3 only suppresses STAT5 phosphorylation only [99, 100]. Taken together, we summarize that blockade of JAK3 activation through anti-γc antibody treatment is enough to suppress γc cytokine-driven NK cell activation while preserve the normal innate functions such as antitumor activity.

Although the blockade of JAK3 activity can inhibit NK cell activation, it is still unclear if γc cytokine-driven NK1 phenotype plays a protective or detrimental role during the progression of autoimmunity. To answer this question, NK cells were purified from PBMC culture, expanded, and cocultured with MSCs to study NK cell-mediated autoimmunity as previously described (73). The current data suggest that IL-2/IL-15 and IL-2/IL-21 costimulation groups induced NK cell autoimmune phenotype (Figure 6) and cytotoxicity against healthy MSCs (Figure 7(b)), while pretreatment with anti-γc antibody in NK cell cultures could rescue the MSCs (Figure 7(c)). These data suggest that γc cytokine-driven NK1 phenotype might play a detrimental role in autoimmune diseases and the corresponding autoimmunity could potentially be reversed through blockade of JAK3 activity. However, the detailed relationship between NK cell activation and development of autoimmunity remains to be studied in vivo.

In humans, upregulation of γc cytokines is usually observed together in various autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis, celiac disease, and vitiligo. The current study suggests that IL-15 might be the major γc cytokine to induce NK cell activation in those patients. For example, IL-15 is overexpressed in the intestinal areas of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [101]. It is demonstrated that intestinal secretion of IL-15 could trigger NK cell-mediated small intestinal inflammation [102]. Prolonged IL-15 treatment to isolated human intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes leads to massive production of IFN-γ and IL-10, eventually resulted in enhanced cytotoxicity against tumor cells [103]. Transgenic mice with intestinal IL-15 overexpression show distinct increase in the numbers of butyrate-producing bacteria, resulting in high susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis [104]. Consistently, IL-15 knockout mice were resistance to DSS-induced colitis, reduced NK cell population and IFN-γ level in lamina propria [105]. More importantly, IL-2 and IL-21 with their receptor subunits are also upregulated in patients diagnosed with IBD [46, 106–109], demonstrating that blockade of multiple γc cytokines through specific inhibition of JAK3 signaling cascade via anti-γc antibody might serve as a potent and safer strategy to treat autoimmune diseases with γc cytokine upregulation. Future studies are required to test whether inhibition of NK cell activity is beneficial in certain autoimmune diseases, such as IBD, in vivo.

5. Conclusion

The current study provides a comprehensive comparison and characterization of γc cytokines in NK cell functions, in which IL-2 and IL-15 stimulate the activated NK1 phenotype while IL-21 preferentially triggers NK cell proliferation. The results are further confirmed with purified NK cells. Specific inhibition of JAK3 signaling cascade by anti-γc antibody could eliminate hyperactivated NK cells and suppress NK autoreactivity in the culture, which may serve as a potent and safer strategy to treat autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the private funding from SinoMab BioScience Limited.

Data Availability

The raw data supporting the statements in this article will be provided by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

WCW, CS, TKT, and CWH are employed by SinoMab BioScience Limited. SOL is the chief executive officer of SinoMab BioScience Limited.

Authors' Contributions

WCW, CS, and CWH prepared and wrote the first draft of article. SOL reviewed and proofread the manuscript. WCW, CS, TKT, and CWH conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. All authors contributed significantly to the current manuscript and approved the submitted version. Wai Chung Wu and Carol Shiu contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

IL-2 and IL-15 promoted Th1/NK1 phenotype in PBMC culture. Supernatant of γc cytokines-treated PBMC culture was harvested for ELISA experiments.

Anti-CD25 and anti-CD122 suppressed IL-2- and IL-15-induced proliferation and activation.

Anti-CD25- and anti-CD122-suppressed IL-2- and IL-15-induced secretion of cytotoxic factors in PBMC culture.

γc cytokines induced NK cell function and activation.

References

- 1.Lodoen M. B., Lanier L. L. Natural killer cells as an initial defense against pathogens. Current Opinion in Immunology . 2006;18(4):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cózar B., Greppi M., Carpentier S., Narni-Mancinelli E., Chiossone L., Vivier E. Tumor-infiltrating natural killer cells. Cancer Discovery . 2021;11(1):34–44. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus A., Gowen B. G., Thompson T. W., et al. Recognition of tumors by the innate immune system and natural killer cells. Advances in Immunology . 2014;122:91–128. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800267-4.00003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmer J., Jurišić V. Special issue “New developments in natural killer cells for immunotherapy”. Cells . 2023;12(11) doi: 10.3390/cells12111496.1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper M. A., Fehniger T. A., Caligiuri M. A. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends in Immunology . 2001;22(11):633–640. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poli A., Michel T., Thérésine M., Andrès E., Hentges F., Zimmer J. CD56 bright natural killer (NK) cells: an important NK cell subset. Immunology . 2009;126(4):458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin Q., Rong L., Jia X., et al. IFN-γ-dependent NK cell activation is essential to metastasis suppression by engineered Salmonella. Nature Communications . 2021;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22755-3.2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cubitt C. C., McClain E., Becker-Hapak M., et al. A novel fusion protein scaffold 18/12/TxM activates the IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 receptors to induce human memory-like natural killer cells. Molecular Therapy-Oncolytics . 2022;24:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2022.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinović K. M. M., Vuletić A. M., Babović N. L., Džodić R. R., Konjević G. M., Jurišić V. B. Attenuated in vitro effects of IFN-α, IL-2 and IL-12 on functional and receptor characteristics of peripheral blood lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Cytokine . 2017;96:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meazza R., Azzarone B., Orengo A. M., Ferrini S. Role of common-gamma chain cytokines in NK cell development and function: perspectives for immunotherapy. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology . 2011;2011:16. doi: 10.1155/2011/861920.861920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vosshenrich C. A., Ranson T., Samson S. I., et al. Roles for common cytokine receptor γ-chain-dependent cytokines in the generation, differentiation, and maturation of NK cell precursors and peripheral NK cells in vivo. Journal of Immunology . 2005;174(3):1213–1221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin J.-X., Leonard W.-J. The common cytokine receptor γ chain family of cytokines. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology . 2018;10(9) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028449.a028449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habib T., Senadheera S., Weinberg K., Kaushansky K. The common γ chain (γc) is a required signaling component of the IL-21 receptor and supports IL-21-induced cell proliferation via JAK3. Biochemistry . 2002;41(27):8725–8731. doi: 10.1021/bi0202023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonard W. J., Lin J.-X., O’Shea J. J. The γc family of cytokines: basic biology to therapeutic ramifications. Immunity . 2019;50(4):832–850. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldmann T. A. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nature Reviews Immunology . 2006;6(8):595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehniger T. A., Cai S. F., Cao X., et al. Acquisition of murine NK cell cytotoxicity requires the translation of a pre-existing pool of Granzyme B and perforin mRNAs. Immunity . 2007;26(6):798–811. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widowati W., Jasaputra D. K., Sumitro S. B., et al. Effect of interleukins (IL-2, IL-15, IL-18) on receptors activation and cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells in breast cancer cell. African Health Sciences . 2020;20(2):822–832. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v20i2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y., Tian Z., Wei H. Developmental and functional control of natural killer cells by cytokines. Frontiers in Immunology . 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00930.930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivashkiv L. B. IFNγ: signalling, epigenetics and roles in immunity, metabolism, disease and cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology . 2018;18(9):545–558. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vuletić A., Jovanić I., Jurišić V., et al. IL-2 and IL-15 induced NKG2D, CD158a and CD158b expression on T, NKT- like and NK cell lymphocyte subsets from regional lymph nodes of melanoma patients. Pathology & Oncology Research . 2020;26:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s12253-018-0444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wendt K., Wilk E., Buyny S., Schmidt R. E., Jacobs R. Interleukin-21 differentially affects human natural killer cell subsets. Immunology . 2007;122(4):486–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raulet D. H., Gasser S., Gowen B. G., Deng W., Jung H. Regulation of ligands for the NKG2D activating receptor. Annual Review of Immunology . 2013;31:413–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kucuksezer U. C., Aktas-Cetin E., Bilgic-Gazioglu S., Tugal-Tutkun I., Gül A., Deniz G. Natural killer cells dominate a Th-1 polarized response in Behçet’s disease patients with uveitis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology . 2015;33(6 Suppl 94):S24–S29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poggi A., Zocchi M. R. NK cell autoreactivity and autoimmune diseases. Frontiers in Immunology . 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00027.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krabbendam L., Heesters B. A., Kradolfer C. M. A., et al. CD127+ CD94+ innate lymphoid cells expressing granulysin and perforin are expanded in patients with Crohn’s disease. Nature Communications . 2021;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26187-x.5841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodge G., Mukaro V., Holmes M., Reynolds P. N., Hodge S. Enhanced cytotoxic function of natural killer and natural killer T-like cells associated with decreased CD94 (Kp43) in the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease airway. Respirology . 2013;18(2):369–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi F.-D., Van Kaer L. Reciprocal regulation between natural killer cells and autoreactive T cells. Nature Reviews Immunology . 2006;6(10):751–760. doi: 10.1038/nri1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ranjkesh M. R., Partovi M. R., Pashazadeh M. The study of serum level of interleukin-2, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in stable and progressive vitiligo patients from Sina Hospital in Tabriz, Iran. Indian Journal of Dermatology . 2021;66(4):366–370. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_300_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharief M. K., Thompson E. J. Correlation of interleukin-2 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor with clinical activity of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry . 1993;56(2):169–174. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tye-Din J. A., Daveson A. J. M., Ee H. C., et al. Elevated serum interleukin-2 after gluten correlates with symptoms and is a potential diagnostic biomarker for coeliac disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics . 2019;50(8):901–910. doi: 10.1111/apt.15477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X.-K., Xu W.-D., Leng R.-X., et al. Therapeutic potential of IL-15 in rheumatoid arthritis. Human Immunology . 2015;76(11):812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2015.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jesús-Gil C., Sans-de San Nicolàs L., García-Jiménez I., Ferran M., Pujol R. M., Santamaria-Babí L. F. Human CLA+ memory T cell and cytokines in psoriasis. Frontiers in Medicine . 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.731911.731911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atwa M. A., Ali S. M. M., Youssef N., Mahmoud Marie R. E.-S. Elevated serum level of interleukin-15 in vitiligo patients and its correlation with disease severity but not activity. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology . 2021;20(8):2640–2644. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Losy J., Niezgoda A., Zaremba J. IL-15 is elevated in sera of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Folia Neuropathologica . 2002;40(3):151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ebrahim A. A., Salem R. M., El Fallah A. A., Younis E. T. Serum interleukin-15 is a marker of alopecia areata severity. International Journal of Trichology . 2019;11(1):26–30. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_80_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abadie V., Jabri B. IL-15: a central regulator of celiac disease immunopathology. Immunological Reviews . 2014;260(1):221–234. doi: 10.1111/imr.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizutani H., Tamagawa-Mineoka R., Nakamura N., Masuda K., Katoh N. Serum IL-21 levels are elevated in atopic dermatitis patients with acute skin lesions. Allergology International . 2017;66(3):440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hao Y., Xie L., Xia J., Liu Z., Yang B., Zhang M. Plasma interleukin-21 levels and genetic variants are associated with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders . 2021;22(1) doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04111-0.246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y., Wang L.-L., Yang H.-Y., Wang F.-F., Zhang X.-X., Bai Y.-P. Interleukin-21 is associated with the severity of psoriasis vulgaris through promoting CD4+ T cells to differentiate into Th17 cells. American Journal of Translational Research . 2016;8(7):3188–3196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Custurone P., Di Bartolomeo L., Irrera N., et al. Role of cytokines in vitiligo: pathogenesis and possible targets for old and new treatments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2021;22(21) doi: 10.3390/ijms222111429.11429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tzartos J. S., Craner M. J., Friese M. A., et al. IL-21 and IL-21 receptor expression in lymphocytes and neurons in multiple sclerosis brain. The American Journal of Pathology . 2011;178(2):794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iervasi E., Auricchio R., Strangio A., Greco L., Saverino D. Serum IL-21 levels from celiac disease patients correlates with anti-tTG IgA autoantibodies and mucosal damage. Autoimmunity . 2020;53(4):225–230. doi: 10.1080/08916934.2020.1736047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang K., Kim H.-O., Kwok S.-K., et al. Impact of interleukin-21 in the pathogenesis of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: increased serum levels of interleukin-21 and its expression in the labial salivary glands. Arthritis Research & Therapy . 2011;13(5) doi: 10.1186/ar3504.R179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira R. C., Simons H. Z., Thompson W. S., et al. IL-21 production by CD4+ effector T cells and frequency of circulating follicular helper T cells are increased in type 1 diabetes patients. Diabetologia . 2015;58(4):781–790. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3509-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dolff S., Abdulahad W. H., Westra J., et al. Increase in IL-21 producing T-cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Research & Therapy . 2011;13(5) doi: 10.1186/ar3474.R157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parkes M., Satsangi J., Jewell D. Contribution of the IL-2 and IL-10 genes to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) susceptibility. Clinical and Experimental Immunology . 1998;113(1):28–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boonpiyathad S., Pornsuriyasak P., Buranapraditkun S., Klaewsongkram J. Interleukin-2 levels in exhaled breath condensates, asthma severity, and asthma control in nonallergic asthma. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings . 2013;34(5):e35–e41. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park Y. B., Kim D. S., Lee W. K., Suh C. H., Lee S. K. Elevated serum interleukin-15 levels in systemic lupus erythematosus. Yonsei Medical Journal . 1999;40(4):343–348. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baranda L., de la Fuente H., Layseca-Espinosa E., et al. IL-15 and IL-15R in leucocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology . 2005;44(12):1507–1513. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuczyński S., Winiarska H., Abramczyk M., Szczawińska K., Wierusz-Wysocka B., Dworacka M. IL-15 is elevated in serum patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice . 2005;69(3):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Konjević G., Vuletić A., Mirjačić Martinović K., Colović N., Čolović M., Jurišić V. Decreased CD161 activating and increased CD158a inhibitory receptor expression on NK cells underlies impaired NK cell cytotoxicity in patients with multiple myeloma. Journal of Clinical Pathology . 2016;69(11):1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-203614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jurisic V. Multiomic analysis of cytokines in immuno-oncology. Expert Review of Proteomics . 2020;17(9):663–674. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2020.1845654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Creelan B. C., Antonia S. J. The NKG2A immune checkpoint—a new direction in cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology . 2019;16(5):277–278. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang C., Wang X.-M., Li S.-R., et al. NKG2A is a NK cell exhaustion checkpoint for HCV persistence. Nature Communications . 2019;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09212-y.1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zamai L., Ahmad M., Bennett I. M., Azzoni L., Alnemri E. S., Perussia B. Natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity: differential use of TRAIL and Fas ligand by immature and mature primary human NK cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine . 1998;188(12):2375–2380. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chua H. L., Serov Y., Brahmi Z. Regulation of FasL expression in natural killer cells. Human Immunology . 2004;65(4):317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voskoboinik I., Whisstock J. C., Trapani J. A. Perforin and granzymes: function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nature Reviews Immunology . 2015;15(6):388–400. doi: 10.1038/nri3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bratke K., Kuepper M., Bade B., Virchow J. C., Jr., Luttmann W. Differential expression of human granzymes A, B, and K in natural killer cells and during CD8 + T cell differentiation in peripheral blood. European Journal of Immunology . 2005;35(9):2608–2616. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aquino-López A., Senyukov V. V., Vlasic Z., Kleinerman E. S., Lee D. A. Interferon gamma induces changes in natural killer (NK) cell ligand expression and alters NK cell-mediated lysis of pediatric cancer cell lines. Frontiers in Immunology . 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00391.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang Y., Day J., Souza-Fonseca Guimaraes F., Wicks I. P., Louis C. Natural killer cells in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Clinical & Translational Immunology . 2021;10(2) doi: 10.1002/cti2.1250.e1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu X.-X., Han T.-T., Xu L.-L., Chang Y.-J., Huang X.-J., Zhao X.-Y. Effect of the in vivo application of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on NK cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine . 2018;22(6):3025–3034. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Higuma-Myojo S., Sasaki Y., Miyazaki S., et al. Cytokine profile of natural killer cells in early human pregnancy. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology . 2005;54(1):21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu J., Gao F.-X., Wang C., et al. IL-6 and IL-8 secreted by tumour cells impair the function of NK cells via the STAT3 pathway in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research . 2019;38(1) doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1310-0.321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang X., Zhao X.-Y. Transcription factors associated with IL-15 cytokine signaling during NK cell development. Frontiers in Immunology . 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.610789.610789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitra S., Leonard W. J. Biology of IL-2 and its therapeutic modulation: mechanisms and strategies. Journal of Leukocyte Biology . 2018;103(4):643–655. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2RI0717-278R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li Y., Li Y., Xiang B., et al. IL-2 combined with IL-15 enhanced the expression of NKG2D receptor on patient autologous NK cells to inhibit Wilms’ tumor via MAPK signaling pathway. Journal of Oncology . 2022;2022:19. doi: 10.1155/2022/4544773.4544773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nandagopal N., Ali A. K., Komal A. K., Lee S.-H. The critical role of IL-15-PI3K-mTOR pathway in natural killer cell effector functions. Frontiers in Immunology . 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00187.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Owen K. L., Brockwell N. K., Parker B. S. JAK-STAT signaling: a double-edged sword of immune regulation and cancer progression. Cancers . 2019;11(12) doi: 10.3390/cancers11122002.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hui C. W., Wu W. C., Leung S. O. Interleukins 4 and 21 protect anti-IgM induced cell death in ramos B cells: implication for autoimmune diseases. Frontiers in Immunology . 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.919854.919854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Shea J. J., Kontzias A., Yamaoka K., Tanaka Y., Laurence A. Janus kinase inhibitors in autoimmune diseases. Annals of The Rheumatic Diseases . 2013;72(suppl 2):ii111–ii115. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Le Floc’h A., Nagashima K., Birchard D., et al. Blocking common γ chain cytokine signaling ameliorates T cell-mediated pathogenesis in disease models. Science Translational Medicine . 2023;15(678) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo0205.eabo0205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Becknell B., Caligiuri M. A. Interleukin-2, interleukin-15, and their roles in human natural killer cells. Advances in Immunology . 2005;86:209–239. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Waldmann T. A. The shared and contrasting roles of IL2 and IL15 in the life and death of normal and neoplastic lymphocytes: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunology Research . 2015;3(3):219–227. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Y., Lundqvist A. Immunomodulatory effects of IL-2 and IL-15; implications for cancer immunotherapy. Cancers . 2020;12(12) doi: 10.3390/cancers12123586.3586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mao Y., van Hoef V., Zhang X., et al. IL-15 activates mTOR and primes stress-activated gene expression leading to prolonged antitumor capacity of NK cells. Blood . 2016;128(11):1475–1489. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-698027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rodella L., Zamai L., Rezzani R., et al. Interleukin 2 and interleukin 15 differentially predispose natural killer cells to apoptosis mediated by endothelial and tumour cells. British Journal of Haematology . 2001;115(2):442–450. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Felices M., Lenvik A. J., McElmurry R., et al. Continuous treatment with IL-15 exhausts human NK cells via a metabolic defect. JCI Insight . 2018;3(3) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.96219.e96219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parrish-Novak J., Dillon S. R., Nelson A., et al. Interleukin 21 and its receptor are involved in NK cell expansion and regulation of lymphocyte function. Nature . 2000;408(6808):57–63. doi: 10.1038/35040504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park Y.-K., Shin D.-J., Cho D., et al. Interleukin-21 increases direct cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production of ex vivo expanded NK cells towards breast cancer cells. Anticancer Research . 2012;32(3):839–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lim D.-P., Jang Y.-Y., Kim S., et al. Effect of exposure to interleukin-21 at various time points on human natural killer cell culture. Cytotherapy . 2014;16(10):1419–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Rham C., Ferrari-Lacraz S., Jendly S., Schneiter G., Dayer J.-M., Villard J. The proinflammatory cytokines IL-2, IL-15 and IL-21 modulate the repertoire of mature human natural killer cell receptors. Arthritis Research & Therapy . 2007;9(6) doi: 10.1186/ar2336.R125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Törnroos H., Hägerstrand H., Lindqvist C. Culturing the human natural killer cell line NK-92 in interleukin-2 and interleukin-15-implications for clinical trials. Anticancer Research . 2019;39(1):107–112. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marçais A., Cherfils-Vicini J., Viant C., et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nature Immunology . 2014;15:749–757. doi: 10.1038/ni.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spaggiari G. M., Capobianco A., Becchetti S., Mingari M. C., Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood . 2006;107(4):1484–1490. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boyiadzis M., Memon S., Carson J., et al. Up-regulation of NK cell activating receptors following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation under a lymphodepleting reduced intensity regimen is associated with elevated IL-15 levels. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy . 2008;14(3):290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.12.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guo Y., Luan L., Rabacal W., et al. IL-15 superagonist-mediated immunotoxicity: role of NK cells and IFN-γ. Journal of Immunology . 2015;195(5):2353–2364. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strengell M., Matikainen S., Sirén J., et al. IL-21 in synergy with IL-15 or IL-18 enhances IFN-gamma production in human NK and T cells. Journal of Immunology . 2003;170(11):5464–5469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wagner J., Pfannenstiel V., Waldmann A., et al. A two-phase expansion protocol combining interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-21 improves natural killer cell proliferation and cytotoxicity against rhabdomyosarcoma. Frontiers in Immunology . 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00676.676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heinze A., Grebe B., Bremm M., et al. The synergistic use of IL-15 and IL-21 for the generation of NK cells from CD3/CD19-depleted grafts improves their ex vivo expansion and cytotoxic potential against neuroblastoma: perspective for optimized immunotherapy post haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Frontiers in Immunology . 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02816.2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aktas E., Akdis M., Bilgic S., et al. Different natural killer (NK) receptor expression and immunoglobulin E (IgE) regulation by NK1 and NK2 cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology . 2005;140(2):301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Crinier A., Dumas P. Y., Escalière B., et al. Single-cell profiling reveals the trajectories of natural killer cell differentiation in bone marrow and a stress signature induced by acute myeloid leukemia. Cellular & Molecular Immunology . 2021;18(5):1290–1304. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Katsumoto T., Kimura M., Yamashita M., et al. STAT6-dependent differentiation and production of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine NK2 cells. Journal of Immunology . 2004;173(8):4967–4975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kucuksezer U. C., Cetin E. A., Esen F., et al. The role of natural killer cells in autoimmune diseases. Frontiers in Immunology . 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.622306.622306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Spolski R., Kim H.-P., Zhu W., Levy D. E., Leonard W. J. IL-21 mediates suppressive effects via its induction of IL-10. Journal of Immunology . 2009;182(5):2859–2867. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Curtis J. R., Yamaoka K., Chen Y.-H., et al. Malignancy risk with tofacitinib versus TNF inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the open-label, randomised controlled ORAL Surveillance trial. Annals of The Rheumatic Diseases . 2023;82(3):331–343. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-222543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ozdede A., Yazıcı H. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. New England Journal of Medicine . 2022;386(18):1766–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2202778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Witalisz-Siepracka A., Klein K., Prinz D., et al. Loss of JAK1 drives innate immune deficiency. Frontiers in Immunology . 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03108.3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gotthardt D., Trifinopoulos J., Sexl V., Putz E. M. JAK/STAT cytokine signaling at the crossroad of NK cell development and maturation. Frontiers in Immunology . 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02590.2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Delconte R. B., Kolesnik T. B., Dagley L. F., et al. CIS is a potent checkpoint in NK cell–mediated tumor immunity. Nature Immunology . 2016;17(7):816–824. doi: 10.1038/ni.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haan C., Rolvering C., Raulf F., et al. Jak1 has a dominant role over Jak3 in signal transduction through γc-containing cytokine receptors. Chemistry & Biology . 2011;18(3):314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu Z., Geboes K., Colpaert S., D’Haens G. R., Rutgeerts P., Ceuppens J. L. IL-15 is highly expressed in inflammatory bowel disease and regulates local T cell-dependent cytokine production. Journal of Immunology . 2000;164(7):3608–3615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ohta N., Hiroi T., Kweon M. N., et al. IL-15-dependent activation-induced cell death-resistant Th1 type CD8αβ+NK1.1+ T cells for the development of small intestinal inflammation. Journal of Immunology . 2002;169(1):460–468. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ebert E. C. IL-15 converts human intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes to CD94 + producers of IFN-γ and IL-10, the latter promoting Fas ligand-mediated cytotoxicity. Immunology . 2005;115(1):118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Meisel M., Mayassi T., Fehlner-Peach H., et al. Interleukin-15 promotes intestinal dysbiosis with butyrate deficiency associated with increased susceptibility to colitis. The ISME Journal . 2017;11(1):15–30. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yoshihara K., Yajima T., Kubo C., Yoshikai Y. Role of interleukin 15 in colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium in mice. Gut . 2006;55(3):334–341. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.076000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mahida Y. R., Gallagher A., Kurlak L., Hawkey C. J. Plasma and tissue interleukin-2 receptor levels in inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical and Experimental Immunology . 1990;82(1):75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Holm T. L., Tornehave D., Søndergaard H., et al. Evaluating IL-21 as a potential therapeutic target in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology Research and Practice . 2018;2018:22. doi: 10.1155/2018/5962624.5962624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang Y., Lv X., Zhan L., et al. Case report: IL-21 and Bcl-6 regulate the proliferation and secretion of Tfh and Tfr cells in the intestinal germinal center of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.587445.587445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fantini M. C., Monteleone G., MacDonald T. T. IL-21 comes of age as a regulator of effector T cells in the gut. Mucosal Immunology . 2008;1(2):110–115. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

IL-2 and IL-15 promoted Th1/NK1 phenotype in PBMC culture. Supernatant of γc cytokines-treated PBMC culture was harvested for ELISA experiments.

Anti-CD25 and anti-CD122 suppressed IL-2- and IL-15-induced proliferation and activation.

Anti-CD25- and anti-CD122-suppressed IL-2- and IL-15-induced secretion of cytotoxic factors in PBMC culture.

γc cytokines induced NK cell function and activation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the statements in this article will be provided by the authors upon request.