Abstract

A cosmid library was constructed for the 350-kb giant linear plasmid SCP1 and aligned on a successive linear map. Only a 0.8-kb gap has remained uncloned in the terminal inverted repeats close to both ends. Partial digestion of the aligned cosmids with EcoRI and hybridization with the flanking fragments of the vector enabled physical mapping of all of the EcoRI fragments. On this map, the methylenomycin biosynthetic gene cluster, the insertion sequence IS466, and the sapCDE genes coding for spore-associated proteins were localized.

Linear plasmids have been found in a variety of eucaryotic species, but have rarely been identified in procaryotic organisms. However, the filamentous soil bacteria Streptomyces spp. possess frequently linear plasmids, which seem therefore to be a significant feature of this genus (12). The plasmids vary in size between 12 kb (28) and 1 Mb (24a). They contain terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) which range between 44 bp in SLP2 of Streptomyces lividans (3) and 95 kb in pPZG101 of Streptomyces rimosus (6). The 5′ ends of all of the plasmids investigated were shown to be blocked by a protein.

Lin et al. (20) first demonstrated that S. lividans has an 8-Mb linear chromosome. The linear chromosome topology has been proved for Streptomyces griseus (19), Streptomyces ambofaciens (18), Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (26), and S. rimosus (25). The close structural similarities between Streptomyces chromosomes and linear plasmids suggest a hypothetical idea that linear plasmids were generated by recombination of linear chromosomes, or circular chromosomes were linearized by integration of a linear plasmid.

SCP1 from S. coelicolor A3(2) is genetically the best-studied linear plasmid. The element long remained unisolated but was postulated on the basis of classical genetic analysis (27). It was shown to carry genes for the biosynthesis of and resistance to the antibiotic methylenomycin (2, 17). With the introduction of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), SCP1 was revealed to be a 350-kb giant linear plasmid containing 80-kb-long TIRs (13, 15).

Considerable attention has been paid to SCP1 because of its interaction with the host chromosome. Freely replicating SCP1 mobilizes chromosomal markers randomly, as seen for all fertility plasmids in Streptomyces. In addition, Hopwood and colleagues isolated mutants carrying an SCP1-chromosome hybrid structure which promotes a directional DNA transfer during conjugation (9, 10). Free SCP1-prime plasmids containing a certain chromosomal DNA stretch were found as well as mutants possessing SCP1 integrated in a central region of the S. coelicolor chromosome. Those SCP1-integrated strains showed either unidirectional or bidirectional DNA transfer with respect to the SCP1 integration site. Preliminary structural analysis of the integrated copies of SCP1 has been carried out for S. coelicolor A3(2) strain 2612 (an NF strain) (8) and strains A608 (a pabA donor) and A634 (an NF-like donor strain) (16).

To reveal in more detail the genetic organization of SCP1 and its role in conjugative DNA transfer, we established an ordered contig of cosmid clones covering most parts of the element.

Generation of an ordered cosmid library.

A cosmid library was prepared for total DNA of S. coelicolor 1147, a wild-type A3(2) strain, which carries both SCP1 and a 31-kb circular plasmid, SCP2 (22). Total DNA was isolated and partially digested with Sau3AI to an average size of 40 to 60 kb. As described previously (26), the DNA was ligated to the vector Supercos-1 (5) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and packaged into lambda phages which were subsequently used to transfect Escherichia coli Sure. Two thousand cosmid clones representing the total genome of S. coelicolor A3(2) were screened with the SCP1 DNA, which was isolated by contour-clamped homogeneous electric fields (CHEF) (4) and nonradioactively labeled with dig-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). A total of 192 clones which hybridized strongly with the SCP1 DNA were obtained.

Supercos-1 possesses T3 and T7 promoters flanking the BamHI cloning site. DNAs of 25 randomly selected clones were isolated and restricted with SalI. The dig-11-dUTP-labeled transcripts of the cosmid ends were generated from the SalI-digested DNAs by using T3 and T7 RNA polymerases. The labeled end probes were hybridized against colony blots of SCP1 clones to identify neighboring cosmid clones. Four additional rounds of hybridizations, including a total of 30 cosmids, were performed to obtain 11 cosmids which could be unambiguously aligned and cover most parts of SCP1 (Fig. 1). Cosmid 31 is completely located within the TIR and was therefore used for the alignment at both ends of SCP1. It was not possible to find a clone among the 192 SCP1 cosmids that reaches closer than 5.0 kb to the very end, because no cosmid hybridized with plasmid pSCP201, which contains the 4.1-kb end SpeI fragment of SCP1 (14).

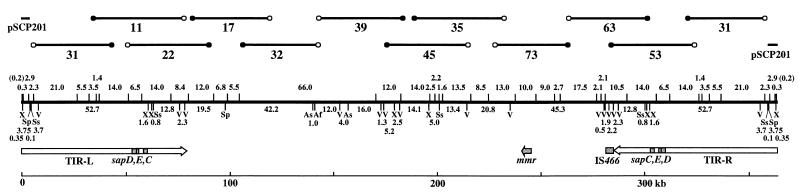

FIG. 1.

Ordered cosmid and restriction maps of SCP1. In the upper part, 12 cosmids covering almost the entire region of SCP1 are aligned on a continuous linear map. The open and solid circles indicate T3 and T7 promoters, respectively. pSCP201, which carries the 4.1-kb terminal SpeI fragment of SCP1 (14), is included at both ends. A gap has remained uncloned between pSCP201 and cosmid 31. The restriction map of SCP1 is drawn in the center. Sites for EcoRI and rare cutting enzymes are shown above and below the SCP1 line. Previous sequence analysis of pSCP201 revealed that five EcoRI sites are present in the 342 nucleotides at the end of SCP1. Among them, four EcoRI sites, the total size of whose fragments is 0.2 kb, were omitted here to avoid complexity, but they are included in Fig. 3A. The sizes of fragments are indicated in kilobases. The positions of the mmr, IS466, and sapCDE genes and two TIRs, left (TIR-L) and right (TIR-R), are shown at the bottom. The transcription direction of the mmr gene (24) is indicated by an arrow. Af, AflII; As, AseI; V, EcoRV; Sp, SpeI; Ss, SspI; X, XbaI.

Construction of the EcoRI fragment map.

To establish a precise restriction map of SCP1, we chose EcoRI as an appropriate enzyme. EcoRI generated a suitable number (about 40) of observable SCP1 fragments and could excise the insert from the vector. Since SCP1 and Supercos-1 contain only two AseI sites, the 4.3- and 0.9-kb AseI-EcoRI fragments of the latter could be used as probes to determine the order of EcoRI fragments. Each cosmid clone was first completely digested with AseI and then partially digested with EcoRI. The partial digest was separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis and hybridized with the 4.3- and 0.9-kb AseI-EcoRI probes separately. This method also confirmed the direction of the insert, because the 4.3- and 0.9-kb fragments carry the T7 and T3 promoters, respectively.

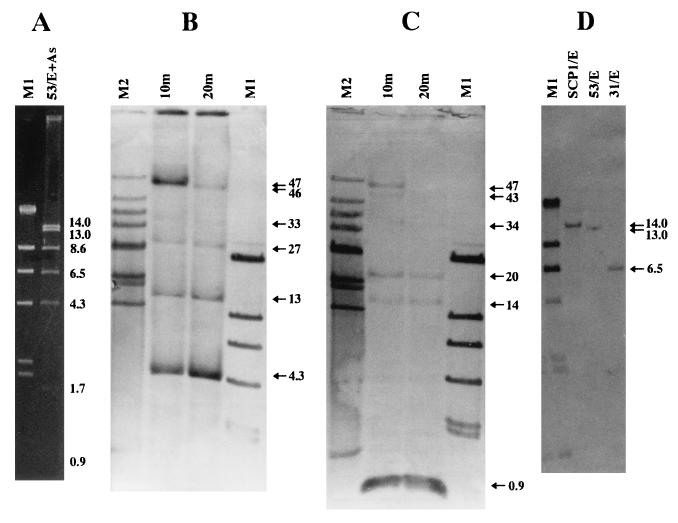

In Fig. 2, the analysis of cosmid 53 is shown as an example. The complete restriction digest of cosmid 53 with AseI and EcoRI gave seven fragments (Fig. 2A): four from the SCP1 DNA (14.0, 13.0, 8.6, and 6.5 kb) and three from the vector DNA (4.3, 1.7, and 0.9 kb). Hybridization of the 4.3-kb AseI-EcoRI probe to the partial EcoRI digest revealed bands of 4.3, 13, 27, 33, 46, and 47 kb (Fig. 2B). This result determined the order of EcoRI fragments from the T7 promoter (right-handed direction) as (4.3)-8.6-14.0-6.5-13.0-(0.9 kb). The same analysis was carried out with the 0.9-kb AseI-EcoRI probe, which showed hybridizing bands of 0.9, 14, 20, 34, 43, and 47 kb (Fig. 2C). The order in the opposite direction from the T3 promoter agreed with the result described above.

FIG. 2.

Restriction analysis of cosmid 53. (A) Conventional agarose gel electrophoresis of the complete digest of SCP1 with AseI and EcoRI. (B and C) Southern hybridization of the partial digest of SCP1. The SCP1 DNA was completely digested with AseI and then partially digested with 3 U of EcoRI in 20 μl of reaction buffer for 10 and 20 min. The restricted DNAs were separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis and transferred to nylon membranes. Hybridization was carried out with two fragments of the vector as a probe: the 4.3-kb AseI-EcoRI fragment (B) and the 0.9-kb AseI-EcoRI fragment (C). (D) Determination of the real size of the rightmost EcoRI fragment of cosmid 53. The SCP1 DNA was digested with EcoRI, separated by conventional agarose gel electrophoresis, and probed with the 13.0-kb right-end fragment of cosmid 53. The EcoRI digests of cosmids 53 and 31 were used as references. M1, λDNA digested with HindIII; M2, λDNA-Mono Cut Mix (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.); E, EcoRI; As, AseI.

The sizes (8.6 and 13.0 kb) of two EcoRI fragments located at the left and right ends of cosmid 53 did not reflect real sizes, because both fragments had been cut by Sau3AI before cloning. The leftmost fragment was detected in the EcoRI digest of the left-hand cosmid 63 and was determined to be 10.5 kb long (data not shown). The size of the rightmost fragment was deduced to be 14.0 kb by hybridization of the 13.0-kb right-end fragment of cosmid 53 to the complete EcoRI digest of SCP1 itself (Fig. 2D). This was confirmed by direct observation of the identical fragment in the EcoRI digest of cosmid 11 due to the TIR (data not shown). All of the aligned cosmids except cosmid 32 were analyzed in this way, and their EcoRI fragment maps were constructed.

Cosmid 32 contains one AseI site but no EcoRI site; thus, a large EcoRI fragment extends over three cosmids, 17, 32, and 39. This large fragment was directly observed by CHEF gel electrophoresis of the EcoRI digest of SCP1 and was determined to be 66 kb long (data not shown).

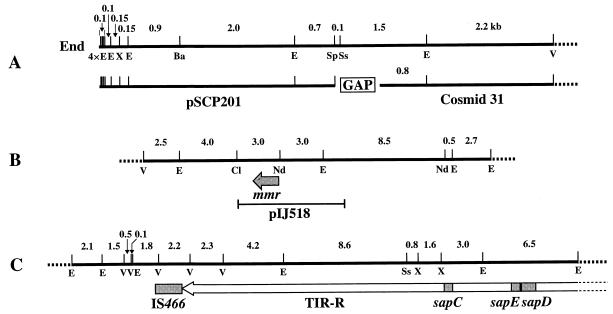

Although cosmid 31 carries a DNA fragment of the TIR region, it does not reach the 4.1-kb end SpeI fragment cloned in plasmid pSCP201 (14). A detailed restriction map at the end of SCP1 was constructed by using pSCP201 and cosmid 31, which revealed that the size of the gap between these clones was 0.8 kb (Fig. 3A). To close the gap, we tried to clone the following five fragments by using three cloning vectors, pUC19, pBR322, and pACYC184, with different copy numbers: the 1.6-kb SpeI-EcoRI fragment, the 2.3-kb EcoRI fragment, the 3.8-kb SpeI-EcoRV fragment, the 7.6-kb XbaI-EcoRV fragment, and the 20-kb BamHI fragment (Fig. 3A). However, we have not succeeded in cloning any of these fragments. This suggests the possibility that the region around the 0.8-kb gap has a special structure unclonable in any of the three vectors or that its protein product has a deteriorative effect on the host.

FIG. 3.

Detailed restriction maps of three regions of SCP1. (A) Terminal region of SCP1. Four EcoRI sites at the extreme end of SCP1 are included in this map. The gap between the SpeI site at the right end of pSCP201 and the Sau3AI site at the left end of cosmid 31 was deduced from this map to be 0.8 kb. (B) mmy region. The positions of the mmr gene and plasmid pIJ518 are shown. The map direction is opposite to that of Chater and Bruton (2). (C) Location of IS466, the right TIR (TIR-R), and the sapCDE genes. E, EcoRI; Ba, BamHI; Cl, ClaI; Nd, NdeI; Sp, SpeI; Ss, SspI; V, EcoRV; X, XbaI.

As a result, the entire region of the SCP1 DNA except for two 0.8-kb gaps close to both ends has been cloned, and all of the EcoRI fragments were aligned on a linear physical map as shown in Fig. 1. We previously reported a map of EcoRV fragments of SCP1 (13). (The number of the EcoRV fragments was corrected to 16, because the 20-kb band was revealed to be a doublet.) All of the EcoRV sites were now located precisely on a linear map by restriction analysis of the ordered cosmids. In addition, all of the recognition sites for AflII, AseI, SpeI, SspI, and XbaI were localized on the same map. The total size of the EcoRI fragments was calculated to be 363.1 kb, which was a little bit larger than the reported size (350 kb) of the intact SCP1 (13). We again tested the size of the intact SCP1 by using Saccharomyces cerevisiae AB972 chromosomes as size markers. The intact SCP1 moved at the same rate with chromosome III (data not shown), whose size is 350 kb according to Link and Olson (21).

Location of the mmy, IS466, and sapCDE genes.

Several genes were reported to be present on SCP1. Chater and Bruton (2) constructed the restriction maps for the methylenomycin biosynthetic gene (mmy) clusters on plasmids SCP1 and pSV1; the latter was suggested to be a 170-kb circular plasmid (1), in contrast to the linear structure of the former. Hybridization experiments with pIJ518 as a probe, which carries the 7.5-kb mmy fragment of SCP1 (2) (Fig. 3B), revealed that the resistance gene (mmr) is located on the 10-kb EcoRI fragment of cosmid 73. The restriction map of the mmy region on cosmid 73 agreed with that of Chater and Bruton (2).

We previously reported that the insertion sequence IS466 (11) is present just at the inside end of the right TIR of SCP1 (14). Analysis of cosmid 63 determined its location on the EcoRI map as shown in Fig. 3C. Guijarro et al. (7) isolated spore-associated proteins SapA and SapB from S. coelicolor A3(2). The sapA gene coding for the former protein has been cloned (7) and was located on AseI fragment F of the chromosome (26). McCormick et al. (23) cloned additional sap genes, sapCDE, which, however, seemed not to be essential for spore formation, because they were mapped to SCP1, and SCP1− strains show no effect on sporulation. Two sets of the sapCDE genes were located in each of both TIR regions, and their restriction maps were constructed (22a). Analysis of cosmid 53 could locate the sapCDE genes on the EcoRI map (Fig. 3C).

Ordered clone libraries have proved to be an excellent tool for analysis of large genomic DNAs. For the 8-Mb S. coelicolor A3(2) chromosome, an ordered cosmid library has been established and used extensively for gene mapping (27), and it is now being used for the genome project in collaboration with the Sanger Centre and the John Innes Centre. Here we reported the generation of an ordered cosmid contig of the giant linear plasmid SCP1, leaving only two 0.8-kb gaps uncloned. A detailed EcoRI restriction map was constructed, and the genetic markers IS466, mmy, and sapCDE were assigned to specific SCP1 fragments. These results will be of great value for study of the structure and function of SCP1 and analysis of the interaction of SCP1 with the chromosome of S. coelicolor A3(2).

Acknowledgments

We thank Keith Chater for plasmid pIJ518; John Cullum for pMT644, which carries IS466; and Joe McCormick for pRC2 and pRD2, which carry a part of sapC and sapD, respectively.

M. Redenbach has been supported by a scholarship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar A, Hopwood D A. Determination of methylenomycin A synthesis by the pSV1 plasmid from Streptomyces violaceus-ruber SANK95570. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:1893–1901. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-8-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chater K F, Bruton C J. Resistance, regulatory and production genes for the antibiotic methylenomycin are clustered. EMBO J. 1985;4:1893–1897. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C W, Yu T-W, Lin Y-S, Kieser H M, Hopwood D A. The conjugative plasmid SLP2 of Streptomyces lividans is a 50 kb linear molecule. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:925–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu G, Vollrath D, Davis R W. Separation of large DNA molecules by contour-clamped homogeneous electric fields. Science. 1986;234:1582–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.3538420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans G A, Lewis K, Rothenberg B E. High efficiency vectors for cosmid microcloning and genomic analysis. Gene. 1989;79:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gravius B, Glocker D, Pigac J, Pandza K, Hranueli D, Cullum J. The 387 kb linear plasmid pPZG101 of Streptomyces rimosus and its interactions with the chromosome. Microbiology. 1994;140:2271–2277. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-9-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guijarro J, Santamaria R, Schauer A, Losick R. Promoter determining the timing and spatial localization of transcription of a cloned Streptomyces coelicolor gene encoding a spore-associated polypeptide. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1895–1901. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1895-1901.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanafusa T, Kinashi H. The structure of an integrated copy of the giant linear plasmid SCP1 in the chromosome of Streptomyces coelicolor 2612. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;231:363–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00292704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopwood D A, Kieser T. Conjugative plasmids of Streptomyces. In: Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopwood D A, Wright H M. Interaction of the plasmid SCP1 with the chromosome of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) In: MacDonald K D, editor. Second International Symposium on the Genetics of Industrial Microorganisms. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 607–619. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall K, Cullum J. Identification of a DNA sequence associated with plasmid integration in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Gen Genet. 1986;202:240–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00331643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinashi H. Linear plasmids from actinomycetes. Actinomycetologica. 1994;8:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinashi H, Shimaji-Murayama M. Physical characterization of SCP1, a giant linear plasmid from Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1523–1529. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1523-1529.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinashi H, Shimaji-Murayama M, Hanafusa T. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the unusually long terminal inverted repeats of giant linear plasmid, SCP1. Plasmid. 1991;26:123–130. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(91)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinashi H, Shimaji M, Sakai A. Giant linear plasmids in Streptomyces which code for antibiotic biosynthesis genes. Nature. 1987;328:454–456. doi: 10.1038/328454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinashi H, Murayama M, Matsushita H, Nimi O. Structural analysis of the giant linear plasmid SCP1 in various Streptomyces coelicolor strains. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1261–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby R, Hopwood D A. Genetic determination of methylenomycin synthesis by the SCP1 plasmid of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Gen Microbiol. 1977;98:239–252. doi: 10.1099/00221287-98-1-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leblond P, Fischer G, Francou F-X, Berger F, Guerineau M, Decaris B. The unstable region of Streptomyces ambofaciens includes 210-kb terminal inverted repeats flanking the extremities of the linear chromosomal DNA. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:261–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.366894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lezhava A, Mizukami T, Kajitani T, Kameoka D, Redenbach M, Shinkawa H, Nimi O, Kinashi H. Physical map of the linear chromosome of Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6492–6498. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6492-6498.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y-S, Kieser H M, Hopwood D A, Chen C W. The chromosomal DNA of Streptomyces lividans 66 is linear. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:923–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link A J, Olson M V. Physical map of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome at 110-kilobase resolution. Genetics. 1991;127:681–698. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.4.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lydiate D J, Malpartida F, Hopwood D A. The Streptomyces plasmid SCP2*: its functional analysis and development into useful cloning vectors. Gene. 1985;35:223–235. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.McCormick, J. R., and R. Losick. Personal communication.

- 23.McCormick J R, Santamaria R, Losick R. The genes for three spore-associated proteins are encoded on linear plasmid SCP1 in Streptomyces coelicolor, abstr. P1-125. Abstracts of the 8th International Symposium on Biology of Actinomycetes, Madison, Wis. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neal R J, Chater K F. Nucleotide sequence analysis reveals similarities between proteins determining methylenomycin A resistance in Streptomyces and tetracycline resistance in eubacteria. Gene. 1987;58:229–241. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Pandza, K., and J. Cullum. Personal communication.

- 25.Pandza K, Pfalzer G, Cullum J, Hranueli D. Physical mapping shows that the unstable oxytetracycline gene cluster of Streptomyces rimosus lies close to one end of the linear chromosome. Microbiology. 1997;143:1493–1501. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-5-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redenbach M, Kieser H M, Denapaite D, Eichner A, Cullum J, Kinashi H, Hopwood D A. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:77–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6191336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vivian A. Genetic control of fertility in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): plasmid involvement in the interconversion of UF and IF strains. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;69:353–364. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X, Roy K L. Complete nucleotide sequence of a linear plasmid from Streptomyces clavuligerus and characterization of its RNA transcripts. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:37–52. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.37-52.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]