Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to synthesize the self‐management theory, model and frameworks of patients with chronic heart failure, focusing on construction process, methods and existing problems.

Background

Although the self‐management theories have been created and verified for those patients with chronic heart failure, no reviews have been performed to integrate these theories.

Design

A scoping review of recent literature (without a date limit) was conducted.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was performed. If the study reported the construction of a self‐management theory, model or framework about chronic heart failure cases, it would be included in the review.

Results

Fourteen studies were included, which could be categorized into situation‐specific theory, middle‐range theory and other theory models (including conceptual model, hypothetic regression model and identity description model). It also includes the update and validation of theories, the situation‐specific theoretical of caregiver contributions extended from situation‐specific theories and the nurse‐led situation‐specific theory in different contexts.

Conclusion

Self‐management might contribute to start an education programme before patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) begin their chronic disease live as an individual. Our scoping review indicates that a series of self‐management theories, models and frameworks for CHF patients have been developed, but more studies are still needed to validate and support these theories according to their cultural contexts.

Keywords: chronic heart failure, frameworks, models, self‐management, theories

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic heart failure (CHF), a systemic disease with high morbidity, mortality and medical expenses, has become a critical and growing health issue that affects 64 million patients globally (Benjamin et al., 2018). The report from the American Heart Association showed that approximately 6.5 million individuals over the age of 20 suffered from CHF, and this number was predicted to be over 8 million by 2030 (Benjamin et al., 2018). The 2020 China report on cardiovascular health and related diseases burden showed that there were 13.7 million patients with CHF (Hu et al., 2020). Pharmacological treatment of CHF has been developed and has significantly reduced in‐hospital mortality. The long‐term outcomes of patients with CHF have not been increased as the readmission rate is still high (Heo et al., 2018; Onkman et al., 2016), which shows that improving the health of people with CHF by relying solely on medical staff is ineffective. In recent decades, self‐management has gradually emerged as an effective and essential way for cases with CHF to improve their long‐term health outcomes. Additionally, it is a crucial part of global guidelines for handling HF (Ponikowski et al., 2016).

Self‐management is used as a synonym for care by oneself, usually refers to the capacity of an individual to handle the symptoms, medication, physical and mental side effects, and lifestyle changes that come with having a chronic ailment (Bullock et al., 2022). Effective self‐management includes the capacity to keep track of one's health and influence the cognitive, behavioural and emotional reactions required to uphold a desirable standard of living. Self‐management in CHF patients is typically viewed as an active cognitive process, which involves medication compliance, fluid and dietary salt limitation, symptom awareness and practice (Chae et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022), exercise and regular follow‐up (Ding et al., 2020). Self‐management can substantially empower patients in addressing issues brought on by heart failure, enhancing their capacity to take part in ongoing medical care, and making better lifestyle decisions (Abbasi et al., 2018; Jordan et al., 2015). Best self‐management is considered to improve drug compliance, which is the key factor for re‐acceptance (Ambardekar et al., 2009), readmission, morbidity and mortality and enhance HF‐related Qol, according to reliable data from systematic reviews (Cui et al., 2019). Self‐management theories, models and frameworks are linked to better endpoint outcomes, such readmission or mortality in CHF patients; however, there is insufficient evidence to support this.

Previous research on CHF patients was largely undertaken based on experience without the direction of self‐management theoretical frameworks, which led to meaningless outcomes in the education intervention, especially in that intervention, which have implemented by the clinical nurse with no academic background. Despite the fact that some reviews have been done in this area, none of them offer a thorough manual for the ‘Theory, Model and Framework (TMF)’ that are now in use for the self‐management of CHF (Bezerra Giordan et al., 2022; Lovell et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021). Everyone has unique insights and methods for helping CHF patients improve their Qol and outcomes through self‐management. Some reviews focused on the effects of different kinds of self‐management intervention methods on CHF (Ha Dinh et al., 2016; Noonan et al., 2019). Self‐management is useful in enhancing CHF patients' outcomes and lessening the stress on their caregivers, according to some evidence. For example, a systematic review to synthesize 15 randomized controlled trials and identified the benefits of self‐management interventions on short and long‐term outcomes in CHF (Zhao et al., 2021). In addition, Noonan et al. (2019) conducted a meta‐analysis to test the effect of involving caregivers in self‐management interventions on health outcomes in CHF. Therefore, a summary of the current TMFs on the self‐management of CHF patients is required, both for professional practice and for patients.

The TMFs of self‐management were constructed to sustain and ease the burden on CHF patients and clinical workers from education to clinical practice and are suggested in many countries (Bezerra Giordan et al., 2022; Cui et al., 2019; Jordan et al., 2015). The choice of an appropriate TMFs at the outset of the study will aid in its successful operation and overall design. The application and selection of TMFs at various levels may be facilitated by synthesizing them to determine their similarities and differences (Ross et al., 2016). To improve the application and selection of TMFs, it is essential to synthesize and identify the existing self‐management TMFs in CHF that have the potential to inform self‐management intervention. Synthesizing TMFs to identify their similarities and differences could facilitate their application and selection at various kinds of levels (Ross et al., 2016). To address these issues, a scoping review and classification of self‐management TMFs in CHF were conducted. Given the scope of the topic areas, the breadth of methodologies used and the magnitude of studies conducted in patients with CHF, a scoping review will prove valuable in investigating the current studies on CHF and helping develop a more effective self‐management intervention.

2. AIM

The aim of this review was to synthesize the self‐management TMFs of CHF patients, focusing on its construction process, methods and existing problems.

3. METHOD

The approach of this scoping review was based on the framework (five steps) of Arksey and O'Malley (2005), which was combined with that from the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al., 2015). This review's workflow was mapped using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA‐ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018) (see Appendix S1). The steps of Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review approach are: (1) defining the research topic; (2) identifying the inclusion studies; (3) selecting studies and extracting data; (4) data analysis and synthesis. The following describes the five steps of Arksey and O'Malley using the JBI search steps of scoping review technique.

3.1. Stage 1: Defining the research topic

The emphasis of this review is on TMFS of self‐managements for CHF patients and how they can assist the transition from the emergency into the stable setting by improving their quality of life and helping them to handle complications. The PICOs (Population, Intervention, Context/comparison, Outcomes and setting) mnemonic promoted the development of the study questions: how do TMFs of self‐management impact CHF patients' ability to manage complication and guide the clinical workers to construct a perfect education system?

3.2. Stage 2: Identifying the inclusion studies

3.2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion were illustrated according to the PICOS for this scoping review. Inclusion criteria: ① the study population was patients with CHF; ② the research content involved the development of TMFs related to self‐management; ③ any study design; and ④ no limitation on the year of publication. Exclusion criteria: ① studies that aimed to analyse the associated factors or develop a theory‐based intervention and ② unable to extract valid information and unable to access the full text after containing the authors.

3.2.2. Search strategy and database search

Two steps were used to develop retrieval strategies to identify relevant studies. The PRISMA 2020 statement guided the whole review process (Page et al., 2021). Two authors (JL and BX) reached an agreement at the outset (available upon request). The literature retrieval followed the PICOS principle, where respectively stood for patients with CHF, self‐management TMFs and any study design if the corresponding study reported specific content of the TMFs.

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), the Chinese Wanfang database and the Chinese VIP database from inception to December 2021 with keywords such as heart failure, cardiac failure, self‐management, theory, model and framework (See Appendix 1). Additional methods were also used to enhance the comprehensiveness of the search (Hopewell et al., 2007; Stansfield et al., 2016), including manual review of bibliographies of relevant studies, citation tracking and retrieval of potential eligible grey studies on websites including http://www.computer scotland.com/Open sigle‐the‐open‐ sesame‐to‐european‐grey‐literature‐1429.php, OPENGREY.EU (http://www.opengrey.eu/), Grey literature Report of the New York Academy of Medicine (http://www.greylit.org/) and Clinical Trials.gov of US National Library of Medicine (https://clinicaltrials.gov/).

3.3. Stage 3: Study selection and data extraction

PRISMA flow diagram guided the study selection process. Two reviewers (Ju‐Lan Xiao and Bai‐Xue Zhan) read all retrieved studies' titles and abstracts. The studies that obviously did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Then, two reviewers (Ju‐Lan Xiao and Bai‐Xue Zhan) read the full text independently according to the pre‐specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancy between two reviewers during study selection was resolved consensus or by a third reviewer (Yang Liu).

3.4. Stage 4: Data analysis and synthesis

Stage four is data extraction, beginning with charting techniques. Two reviewers independently extracted data with a standardized data extraction table predefined based on the PICOS principle. The extracted information included the studies' characteristics (such as journal, first author, year of publication, study design, study setting/location, sample size if available), the model's name and connotation, and whether the model was validated. When the required information was missing, a reviewer would contact the author to request the corresponding data. It would be coded as ‘unreported’ if the required information were unavailable. After the charting process, in order to ensure the accuracy and validity of the results, all researchers conducted a final review of all included research and the data extraction table. Consensus on article inclusions and interpretation of the results was reached through team discussion (six steps). Three types of theory were identified based on philosophical categories; this includes middle‐range theory, situation‐specific theory and other theory models (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Information of the inclusion study.

| Study | Country | Design (type) | Setting/location | Sample size | Main outcome | The main propositions put forward | Whether to validate | Subject affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbara Riegel et al. (2012) | US | It is based on the Situation‐Specific theory (review) | Three hypotheses and seven propositions are proposed | Not mentioned | A Middle‐Range Theory of Self‐Care of Chronic Illness | The key concepts include self‐care maintenance, self‐care monitoring and self‐care management. Factors influencing self‐care including experience, skill, motivation, culture, confidence, habits, function, cognition, support from others and access to care are described | No | Advances in Nursing Science |

| Tiny Jaarsma et al. (2017) | US | Take the form of a review (summary) | Summarize the recent heart failure literature on these related factors in order to provide an overview on which factors might be suitable to be considered to make self‐care interventions more successful | 14 studies | Update of Riegel's middle‐range Theory | Experiences and skills, motivation, habits, cultural beliefs and values, functional and cognitive abilities, confidence and support and access to care are all important to consider when developing or improving interventions for patients with heart failure and their families | No | Curr Heart Fail Rep |

| Sumayya A. Attaallah et al. (2021) | US | After integrating theoretical and empirical literature, a hypothetico‐deductive approach was used to develop theory (review) | Describes the strategy used in developing a middle‐range theory of heart failure self‐care. After integrating theoretical and empirical literature, a hypothetico‐deductive approach was used to develop the middle‐range theory of heart failure self‐care from Orem's theory of self‐care | Not mentioned | Middle‐Range Theory of Heart Failure Self‐Care | 7 associated proposition for the MRT of HF self‐care were mentioned | No | Nursing Science Quarterly |

| Sumayya A. Attaallah et al. (2021) | US | A middle‐range theory of heart failure self‐care, derived from the self‐care deficit theory of nursing, was tested among 175 Arab American older adults with heart failure (descriptive research) | 175 patients were recruited from four cardiology clinics. Instruments to assess HF influential factors include a personal survey, health care index, the Center for Epidemiological Studies‐Depression Scale‐10, Arabic‐Speaking Patients' Acculturation Scale and Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey | 175 patients | Testing a Middle‐Range Theory of Heart Failure Self‐Care | Conceptualizing basic conditioning factors as a single latent variable was not supported. However, individual factors of depression, social support and time living with heart failure had a direct effect on both self‐care agency and quality of life | Yes | Nursing Science Quarterly |

| Barbara Riegel et al. (2008) | US | Four propositions were derived from the self‐care of heart failure conceptual model. These propositions were tested and supported using data obtained in previous research (descriptive research) | Naturalistic decisions are involved. Crucial elements included a nursing perspective; a clear link among the theory, research and clinical practice; and a conceptual scheme based on abstract thinking, memo or journal writing and dialogue with colleagues, students and research participants | 760 patients | A Situation‐Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self‐care | Two concepts of self‐care management and self‐care maintenance were proposed. Confidence is thought to influence the self‐care process in important ways | Yes | Cardiovascular Nursing |

| Barbara Riegel et al. (2016) | US | Describe this revised, updated situation‐specific theory of HF self‐care. A total of 5 assumptions and 8 testable propositions are specified in this revised theory (review) | Designing the middle‐range theory and studying the literature citing the situation‐specific theory led us to conclude that this theory needs revision and updating. Propose propositions and hypotheses, search databases, search literature using context‐specific theories and test propositions and hypotheses | 85 relevant articles were retained | Updated situation‐specific theory of HF self‐care | A third concept, symptom perception, has been added to the theory; each process includes both autonomous and consultative elements; this revised theory is more closely integrated with the naturalistic decision‐making elements of person, problem and environment and with the self‐care decisions made by patients with HF while acknowledging how these decisions are influenced by knowledge, skills, experience and values | Partly | Cardiovascular Nursing |

| Barbara Riegel et al. (2022) | US | Describe the manner in which characteristics of the problem, person and environment interact to influence decisions about self‐care made by adults with chronic HF.(review) | Literature on the influence of the problem, person and environment on HF self‐care is summarized | Not mentioned | Updated situation‐specific theory of HF self‐care |

We know that the problem, person and environment influence self‐care decisions, but here, we emphasize the interaction among these three factors New emphasis is placed on environmental factors influencing self‐care: weather, crime, violence, access to the Internet, the built environment, social support and public policy Seven new theoretical propositions are included in this update |

No | Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing |

| Ercole Vellone et al. (2017) | Italy | Describe a Situation‐Specific Theory of Caregiver Contributions to HF Self‐care (descriptive research) | Describe theoretical assumptions, recursive pathways are hypothesized between processes and outcomes. Ten theoretical propositions are proposed | Not mentioned | A Situation‐Specific Theory of Caregiver Contributions to Heart Failure Self‐care | Caregiver contributions to HF self‐care include interacting processes of self‐care maintenance, symptom monitoring and perception and self‐care management. Caregiver confidence and cultural values are discussed as important influences on caregiver contributions to HF self‐care | No | Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing |

| Oliver Rudolf Herber et al. (2018) | Germany | Used meta‐synthesis techniques to integrate statements of findings pertaining to barriers and facilitators to heart failure self‐care that were derived previously through meta‐summary techniques leading to a new situation‐specific theory (meta‐synthesis) | Developed the theory based on the statements of findings that were derived through meta‐summary techniques. The integration process involved the use of ‘imported concepts’ which are generally accepted as true to address our phenomena. Finally, the theory was refined through continuous discussions | 37 initially, 814 patients | A situation‐specific theory pertaining to barriers (−) and facilitators (+) for self‐care in patients with heart failure | According to our proposed theory, self‐care behaviour is the result of a patient's naturalistic decision‐making process. This process is influenced by two key concepts: ‘self‐efficacy’ and the ‘patient's disease concept of heart failure’ | No | Qualitative Health Research |

| Hui‐Wan Chuang et al (2019) | Taiwan | Examine how depressive symptoms, social support, eHealth literacy and heart failure (HF) knowledge directly and indirectly affect self‐care maintenance and management and to identify the mediating role of self‐care confidence in self‐care maintenance and management (descriptive research) | Analysed patient's data, including demographic and clinical characteristics, obtained from 5 scale. Then, path analysis was conducted to examine the effects of the study variables on self‐care maintenance and management | 141 patients | Self‐care confidence significantly and directly affected self‐care maintenance and management and mediated the relationships between factor variables (depressive symptoms, social support and HF knowledge) and outcome variables (self‐care maintenance and management) | Self‐care confidence decreases the negative effects of depressive symptoms on self‐care. This study underscores the need for interventions targeting patients' self‐care confidence to maximize self‐care among patients with HF | No | Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing |

| Yuanyuan Jin et al. (2021) | US | Describe the development of a situation‐specific nurse‐led culturally tailored self‐management theory for Chinese patients with HF (descriptive research) | An integrative approach was used as theory development strategy for the situation‐specific theory. The proposed theory is derived from Leininger's culture care theory (CCT) and Prochaska's transtheoretical model (TTM) | Not mentioned | Based on theoretical and empirical evidence and theorists' experiences from research and practice, a nurse‐led culturally tailored self‐management theory for Chinese patients with HF was developed | The situation‐specific theory developed in this study has the potential to increase specificity of existing theories while informing the application to nursing practice. Further critique and testing of the situation‐specific theory | No | Journal of Transcultural Nursing |

| Jennifer Wingham et al. (2014) | UK | Meta‐ethnography (qualitative research) | A multidisciplinary team of academics, clinicians and patient representatives in the United Kingdom | 19 qualitative research studies | Conceptual model of self‐management heart failure | Patients pass through five stages as they seek a sense of safety and well‐being when living with HF, including disruption, sense making, reaction, response and assimilation | No | Chronic illness |

| Elliane Irani et al. (2019) | US | Validate components of the Individual and Family Self‐management Theory among individuals with HF (descriptive research) | A path analysis was conducted to examine the indirect and direct associations among social environment, social facilitation and belief processes and self‐management behaviours while accounting for individual and condition‐specific factors | 370 patients | The Contribution of Living Arrangements, Social Support and Self‐efficacy to Self‐management Behaviours Among Individuals With Heart Failure | Support the Individual and Family Self‐management Theory, highlighting the importance of social support and self‐efficacy to foster self‐management behaviours for individuals with HF. Future research is needed to further explore relationships among living arrangements, perceived and received social support, self‐efficacy and HF self‐management | No | Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing |

| Barbara Riegel et al. (2011) | US | Validate the novice‐to‐expert self‐care typology and to identify determinants of the heart failure self‐care types (descriptive research) | Two‐step likelihood cluster analysis was used to classify patients into groups using all items in the maintenance and management scales of the Self‐care of Heart Failure Index. Multinomial regression was used to identify the determinants of each self‐care cluster, testing the influence of age and so on | 689 patients | Self‐care behaviours clustered best into three types | Duke Activity Status Index score and Self‐care of Heart Failure Index confidence score were the only statistically significant individual factors. Higher activity status increased the odds that patients would be inconsistent or novice in self‐care. Higher self‐care confidence increased the odds of being an expert or inconsistent in self‐care | No | Nursing Research |

4. RESULTS

4.1. Study characteristics

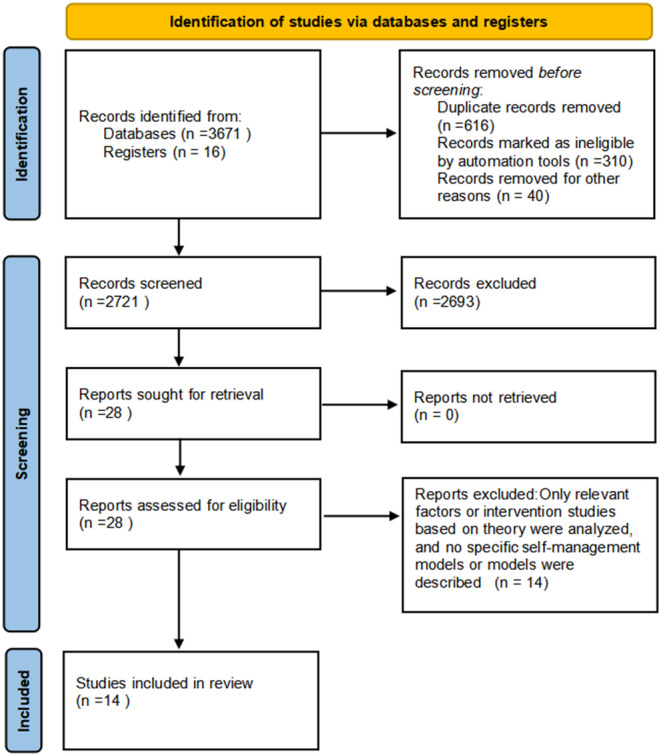

A total of 3687 studies were retrieved, of which 16 were retrieved through the manual search of bibliographies of retrieved literature. After removing duplicates and other reasons (n = 966), 2721 studies were screened according to reading title and abstract, and 2693 were excluded. Twenty‐eight studies were further retrieved for full‐text screening. Fourteen studies were included (see Table 1), and other 14 studies were excluded (see Table 2) in this scoping review after group discussion. The included studies could be categorized into mild‐range theory (n = 4), situation‐specific theory (n = 7), conceptual model (n = 1), hypothetic regression model (n = 1) and novice‐to‐expert self‐care model (n = 1). The process of research selection is shown in Figure 1.

TABLE 2.

Reasons to exclude studies after full‐text screening.

| Study | Country | Reasons |

|---|---|---|

| Sue W et al. (2008) | US | Comments on conceptual models |

| Bradi B. G et al. (2008) | US | Examine gaps in the understanding of the heart failure experience and describe the use of chronic disease tracks |

| Nancy Jean G et. al (2011) | US | This paper reviews the research results and future directions of self‐management in patients with heart failure |

| Xiaofeng K et al. (2012) | China | The objectives was to explore patients' preferences of self‐management using Q‐methodology |

| Efstathia A et al. (2014) | US | The objective of this review is to propose a conceptual model for heart failure (HF) disease management (HFDM) and to define the components of an efficient HFDM plan in reference to this model |

| Serena B et al. (2015) | Italy | Theoretical study on doctor‐patient relationship in the management of heart failure hospital |

| Julie T. B et al. (2015) | US | The purpose of this study was to identify determinants of patient and caregiver contributions to HF self‐care maintenance (daily adherence and symptom monitoring) and management (appropriate recognition and response to symptoms), utilizing an approach that controls for dyadic interdependence |

| Stefano B et al. (2016) | Italy | In general, through cooperation with Austrian healthcare and medical insurance providers. Detailed data on more than 3000 inpatient and 11,000 out‐of‐hospital care patients over a 6.5‐year time span can be evaluated and used as a traditional care model structure |

| Reiko A et al. (2021) | US | Provide a conceptual rationale for targeted self‐management strategies for breathlessness in chronic heart failure |

| Amanda W et al. (2021) | Germany | To outline how the COM‐B behavioural model has been applied to guide the development of a theory‐based intervention aiming to improve adherence to heart failure self‐care recommendations |

| Chen, Cancan et al. (2022) | China | This study aimed to determine whether resilience and self‐efficacy play multiple mediating roles in the association between mutuality and caregiver contributions to heart failure self‐care |

| Siennicka, A et al. (2022) | Poland | The aim of this study is to examine, based on the model of ‘locus of control’, whether there are different patterns that would be relevant for a more targeted education and support of self‐management in dealing with heart failure |

| Hirano, GSB et al. (2023) | Brazil | Explained and described the health management of outpatients with heart failure by the situation‐specific theory |

| Kim, Da‐Young et al. (2023) | Korea | This study aimed to identify distinct trajectories of self‐care behaviours over 6 months after hospital discharge in patients with heart failure, including the baseline predictors affecting these trajectories |

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the study selection procedure.

4.2. Middle‐range theories (MRTs)

MRTs, as originally purported by Merton (1968), are theories that lie between a working hypothesis and a broad, abstract grand theory. Their principal use is to guide empirical inquiry. MRTs start with a focused concept phenomenon to create theoretical statements that can be empirically tested, allowing verification of the theoretical propositions (Attaallah et al., 2021a).

Riegel developed a middle‐range theory of self‐care in chronic disease in 2012 (Riegel et al., 2012) based on his situation‐specific theory of self‐care in CHF patients in 2008 and updated in 2017 to include factors associated with self‐care of CHF patients (Attaallah et al., 2021a). Riegel showed a graphic representation of the conceptual‐theoretical‐empirical structure based on the theoretical substructure to demonstrate the coherence between the operational and theoretical system. Attaallah proposed a middle‐range theory of heart failure self‐care and validated it in 2021 (Attaallah et al., 2021a, 2021b). This theory was developed by adopting the hypothetico‐deductive approach from Orem's self‐care theory based on integrating theoretical and empirical studies.

4.3. Situation‐specific theories

The earliest and most widely used theory was the situation‐specific theory of self‐care in CHF patients, developed by Riegel in 2008 (Riegel & Dickson, 2008). It originated from the conceptual model constructed from a study on developing a tool to measure the self‐management ability of CHF patients (Riegel et al., 2000). In previous studies, self‐care was defined as a rational process including goal‐directed selections and behaviours, reflecting knowledge and idea. The key concepts of this model were maintenance and management. This theory was updated in 2016 and 2022 respectively. In the 2016 update, self‐care was redefined as a naturalistic decision‐making process including the choice of behaviours that maintain physiological stability (maintenance) and the response to symptoms when they appear (management) (Riegel et al., 2016). In the 2022 update, the interaction among the problem, person and environment was be emphasized, and seven new theoretical propositions were included (Riegel et al., 2022).

Vellone et al. (2019) described a theory of caregiver contributions to heart failure self‐care in 2018. This theory assumed recursive paths between processes and outcomes and put 10 theoretical propositions forwards, but these propositions were not validated.

Herber et al. (2019) developed a theoretical model of self‐care barriers and facilitators in CHF patients in 2018 through qualitative meta‐summary and meta‐synthesis. In this study, 31 included qualitative studies were analysed following the steps of (1) testing the hypothesis of theoretical development, (2) exploring through various sources, (3) theorizing and (4) reporting, sharing and verifying the developed theories.

Chuang et al. (2019) surveyed 141 patients with CHF using multiple scales and performed a path analysis to test the influence of research variables on self‐care management and maintenance. The results suggested that there was a direct and negative impact of depressive symptoms on self‐care maintenance, while e‐health literacy was directly and positively related to self‐care management. In addition, knowledge of heart failure and social support can indirectly improve self‐care maintenance and self‐care management mediated by self‐care confidence. Therefore, it supported Riegel's situation‐specific theory of heart failure self‐care.

Jin and Peng (2022) developed a situation‐specific theory of nurse‐led self‐management conforming to local culture for Chinese heart failure patients by integrative approach in 2021. This theory was developed in the same steps as Oliver Rudolf Herber's study, which integrated Leininger's culture care theory (CCT) and Prochaska's transtheoretical model (TTM).

4.4. Other theory models

Other than situation‐specific theory and mid‐range theory are grouped into other theory models.

4.4.1. Conceptual models

Wingham et al. (2014) proposed a conceptual model of self‐management attitudes, beliefs, expectations and experiences of heart failure patients by meta‐integrating 19 qualitative studies. Before building a mental model of heart failure, patients would experience a sense of disruption, whose responses included being a strategic avoider, alternative denier, well‐meaning manager or advanced self‐manager. The patients' response is to develop self‐management tactics and ultimately incorporating them into their daily lives to seek a sense of security.

This research was a part of the Rehabilitation Enablement in Chronic Heart Failure (REACH‐HF) study group's work dedicated to conducting and examining an evidence‐based home‐based cardiac rehabilitation project for patients with heart failure using a complex intervention framework. This programme focused more on the psychological aspects, intending to provide patients with CHF with a tool for self‐management so that individuals could adapt to life with heart disease.

4.4.2. Hypothetic regression model

Hypothetic regression model was presented by (Irani et al. (2019)). In this study, the authors secondarily analysed the data from a longitudinal descriptive study that investigated 370 patients with heart failure using multiple scales through the methods of statistical package for social science and analysis of moment structures.

The authors conducted a secondary analysis of data from a longitudinal descriptive study of 370 heart failure patients and drew the following conclusions: (1) social support and living arrangements had a positive effect on patients' self‐efficacy and HF self‐management behaviour; (2) social support mediated the effect of living arrangements on HF self‐management behaviours. Clinicians should consider how to incorporate informal caregivers into managing CHF patients and improve the quality of support they provide to patients to improve patients' self‐efficacy and cultivate their self‐management behaviours. Individual and family self‐management theories can be used as frameworks for understanding the critical factor for self‐management in HF patients.

4.4.3. Identity theory of heart failure patients

There was a theory developed by Riegel et al. (2011) based on a cross‐sectional descriptive study performed on 689 heart failure patients in 2011. This study applied a two‐step likelihood cluster analysis to group patients by using the Self‐care of Heart Failure Index. Then, multinomial regression was conducted to evaluate how variables such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), left ventricular ejection fraction, anxiety, depression, hostility, perceptual control, social support and activity status affect the self‐care of patients in different groups. The results of this study verified the three‐level typology of self‐care of patients with CHF, such as novice, expert and inconsistent person. Patients who are new to self‐care are more likely to have insufficient confidence and limited mobility. Conversely, patients who can care for themselves proficiently (experts) were likely to show confidence in their self‐care ability. In addition, patients who were inconsistent in self‐care were more likely to be confident in their self‐care abilities and have few activity limitations. The description of the included literature is shown in Table 1.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Main contents of self‐care theoretical model of patients with CHF

This scoping review identified five main types of self‐care theory for patients with CHF, involving 13 studies, with the dominant theory types being middle‐range theory and situation‐specific theory. Nursing theory was mainly based on abstract grand theory, such as Orem's self‐care theory (Khademian et al., 2020). However, middle‐range theory and situation‐specific theory, which are more practical and verifiable, began to emerge in the 1980s and gradually became the mainstream of contemporary theory, building bridges among theory, research and practice (Hough, 1989; Mullins, 2006; Ordway et al., 2014). Since the grand theories related to self‐care were esoteric in terms and vague in concepts, it is difficult to guide clinical practice. Therefore, the middle‐range theory and situation‐specific self‐care theory in a specific population, such as patients with CHF, have been gradually developed.

5.2. Characteristics of theoretical development methods and contents

‘Theory’ is an umbrella term for a theoretical framework, theoretical model and theory (Attaallah et al., 2021a; Im, 2018; Walker & Avant, 2011). The premise of theory development is to formulate a hypothesis (such as a belief about an underlying fact), and only by accepting this belief can a theory constructed based on this belief be accepted (Im, 2005; Im & Meleis, 1999). Theory composes of two fundamental elements: concepts and the relationship between concepts (Im & Meleis, 1999; McEwen & Wills, 2019; Walker & Avant, 2011). If comparing the development of theory to building a wall, the ‘concept’ is the bricks used for building the wall, and the ‘relationship between concepts’ is the level and direction of the bricks (Im, 2014; McEwen & Wills, 2019). Thus, the primary content of theoretical construction should include the definition of concepts, the development of relationships between concepts and the logical position of basic elements in the theoretical framework.

Lierhr and Smith, based on the construction of Lenz theory, summed up five ways to construct the middle‐range theory: (1) using induction method to develop theory from practice and research (such as from individual to general); (2) reasoning from ground theory by deductive method to form middle‐area theory (from general to individual); (3) adopting the recombination method to extract concepts and the relationship between concepts from the existing middle‐range theories of nursing and non‐nursing disciplines to integrate them into a new theory; (4) directly introducing related theories from other disciplines; and (5) developing theory from the existing clinical practice guidelines and nursing practice standards. The middle‐range theory of heart failure self‐care proposed by Attaalla (Attaallah et al., 2021a) was developed according to the second way. It was derived from Orem's self‐care theory and developed underlain the summary of empirical research evidence and subsequently verified; hence, it could be widely promoted and applied. The conceptual model about self‐care proposed by Jennifer Wingham (Wingham et al., 2014) is constructed in line with the first way; however, it has problems such as in‐comprehensive literature retrieval, including qualitative studies exclusively, and unverified.

Meleis put forward the concept of ‘situation‐specific theory’ in the mid‐1990s (Meleis, 2017). She believes that situation‐specific theories target specific nursing phenomena, population cultures and practices, which are smaller in scope, more specific and more applicable to nursing practice situations than the middle‐range theory (Meleis, 2017). Based on Meleis' comprehensive theory construction strategy, we formulated a set of approaches to construct the situation‐specific theory in 2005 (Im, 2005), which included four steps. Firstly, the premise hypothesis should be determined. Before constructing a situation‐specific theory, theory developers need to admit four assumptions, such as the existence of multiple truths, the essence of continuous evolution and development of theory, the unique socio‐cultural characteristics of different nursing phenomena, and the necessity of analysing phenomena and problems from the nursing perspective. Second, to integrate multi‐faceted resources, such as the existing theories, research, education, clinical practice experience and international cooperation in the same research field of nursing and non‐nursing professionals. Third, to determine a comprehensive scheme for theoretical construction after having the initial motivation for theoretical construction. Ideas for theory building can be triggered by literature readings, personal clinical practice experiences and the theory needs to be identified during collaborative research, or even discussions among colleagues. Fourth, to report, validate and promote the theory. In this scoping review, the included situation‐specific theories are all constructed according to the above methods.

The development process of situation‐specific theories can be varied. Riegel used quantitative results from their previous research (Riegel et al., 2012, 2016; Riegel & Dickson, 2008). It would need to be tested by the work of others to be really powerful. A culturally tailored self‐management theory can guide the practice of providing patient‐centred care for patients with chronic conditions by considering the factors of their cultural and stage of change (Jin & Peng, 2022). Then, Herber's situation‐specific theory was based entirely on a qualitative paradigm, that is, a qualitative meta‐summary and meta‐synthesis approach, requiring empirical testing to support relationships between variables (Herber et al., 2019).

5.3. Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, we only retrieved English and Chinese studies, which might lead to bias in results. Second, some of the included theories have not been validated, so it is uncertain whether they are valid or applicable. Finally, we did not find a suitable tool to evaluate the quality of the included studies due to the inclusion of various types of articles in this scoping review, such as reviews, meta‐analyses and meta‐integrations. Due to the lack of uniformity in included studies, the bias assessment was unable to be provided. Therefore, the results of this study should be carefully interpreted.

6. CONCLUSION

Various self‐management TMFs for CHF patients have been developed, but more studies are still needed to validate and support these theories. With increasing studies on the construction of self‐care theories for patients with heart failure, we believe these theories can guide future research and help scholars gather relevant knowledge. Therefore, we suggest that researchers can validate specific theories according to their own cultural contexts to help develop this field of science. At the same time, in the process of validating these TMFs, medical staff could constantly learn from the self‐management experience of patients with CHF, thereby improving the self‐management level of this population and further reducing their readmission rate and mortality.

7. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

Self‐management might contribute to start an education programme before CHF patients begin their chronic disease live as an individual. The findings from this scoping review identified that there were a series of TMFs of self‐management on CHF patients. And, they required support and more resources to prepare a health life in future, especially at home without the professional medical staffs. Education courses about dealing with complications and health skills and training for CHF patients might be helpful for supporting self‐management in dealing with these problems. Little is known about how health professionals select TMFs according to the situation when implementing self‐management‐related health education for CHF patients. Little is also known about the self‐management experiences of CHF patients during programme implementation. In addition, no studies have discussed the importance of starting TMF, especially as medical staffs are completing their self‐management programmes and are on their way to becoming research nurses. Thus, We suggest that researchers can validate specific theories according to their cultural contexts and develop culture‐tailored self‐management intervention protocol, thereby improving the self‐management level of this population and further reducing their readmission rate and mortality.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jie Chen, Yan‐Ni Wu and Wei‐Xiang Luo contributed to the study design. Jie Chen, Xiu‐Fen Yang, Ju‐Lan Xiao and Bai‐Xue Zhan contributed to the development of the eligibility criteria. Jie Chen and Yang Liu contributed to the data extraction criteria and the search strategy. Jie Chen and Xiu‐Fen Yang contributed to the review approach design, data analysis and writing manuscript. Jie Chen, Ju‐Lan Xiao and Yan‐Ni Wu contributed to the revisions to the scientific content of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No fundings.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all participants.

APPENDIX 1. Example of the search strategy in Medline, Embase, Cochrane and PubMed databases.

| Searches | Keywords |

|---|---|

| 1 | Heart failure. mp |

| 2 | Cardiac failure. mp |

| 3 | Chronic heart failure. mp |

| 4 | Congestive heart failure. mp |

| 5 | CHF |

| 6 | Myocardial failure. mp |

| 7 | Heart decompensation. mp |

| 8 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 |

| 9 | Self‐manage. mp |

| 10 | Self‐Care. mp |

| 11 | Symptom*‐Manage. mp |

| 12 | Self‐Monitor. mp |

| 13 | Self‐Control. mp |

| 14 | Self‐Help. mp |

| 15 | Disease management. mp |

| 16 | Self‐Govern. mp |

| 17 | Self administrations. mp |

| 18 | 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 OR 17 |

| 19 | Theory. mp |

| 20 | Model. mp |

| 21 | Framework. mp |

| 22 | 19 OR 20 OR 21 |

| 23 | 8 AND 18 AND 22 |

Chen, J. , Luo, W.‐X. , Yang, X.‐F. , Xiao, J.‐L. , Zhan, B.‐X. , Liu, Y. , & Wu, Y.‐N. (2024). Self‐management theories, models and frameworks in patients with chronic heart failure: A scoping review. Nursing Open, 11, e2066. 10.1002/nop2.2066

Wei‐xiang Luo and Jie Chen contributed equally to this paper.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable—no new data are generated.

REFERENCES

- Abbasi, A. , Najafi Ghezeljeh, T. , Ashghali Farahani, M. , & Naderi, N. (2018). Effects of the self‐management education program using the multi‐method approach and multimedia on the quality of life of patients with chronic heart failure: A non‐randomized controlled clinical trial. Contemporary Nurse, 54(4–5), 409–420. 10.1080/10376178.2018.1538705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambardekar, A. V. , Fonarow, G. C. , Hernandez, A. F. , Pan, W. , Yancy, C. W. , & Krantz, M. J. (2009). Characteristics and in‐hospital outcomes for nonadherent patients with heart failure: Findings from get with the guidelines‐heart failure (GWTG‐HF). American Heart Journal, 158(4), 644–652. 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a meth odological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attaallah, S. A. , Peters, R. M. , Benkert, R. , Yarandi, H. , Oliver‐McNeil, S. , & Hopp, F. (2021a). Developing a middle‐range theory of heart failure self‐care. Nursing Science Quarterly, 34(2), 168–177. 10.1177/0894318420987164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attaallah, S. A. , Peters, R. M. , Benkert, R. , Yarandi, H. , Oliver‐McNeil, S. , & Hopp, F. (2021b). Testing a middle ‐range theory of heart failure self‐care. Nursing Science Quarterly, 34(4), 378–391. 10.1177/08943184211031590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, E. J. , Virani, S. S. , Callaway, C. W. , Chamberlain, A. M. , Chang, A. R. , Cheng, S. , Chiuve, S. E. , Cushman, M. , Delling, F. N. , Deo, R. , de Ferranti, S. D. , Ferguson, J. F. , Fornage, M. , Gillespie, C. , Isasi, C. R. , Jiménez, M. C. , Jordan, L. C. , Judd, S. E. , Lackland, D. , … American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . (2018). Heart disease and stroke Statistics‐2018 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality & Outcomes, 137(12), e67–e492. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra Giordan, L. , Tong, H. L. , Atherton, J. J. , Ronto, R. , Chau, J. , Kaye, D. , Shaw, T. , Chow, C. , & Laranjo, L. (2022). The use of Mobile apps for heart failure self‐management: Systematic review of experimental and qualitative studies. JMIR Cardio, 6(1), e33839. 10.2196/33839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, B. , Learmonth, C. , Davis, H. , & Al Mahmud, A. (2022). Mobile phone sleep self‐management applications for early start shift workers: A scoping review of the literature. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 936736. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.936736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae, S. , Song, J. , Ojo, M. , Bowles, K. H. , McDonald, M. V. , Barrón, Y. , Hobensack, M. , Kennedy, E. , Sridharan, S. , Evans, L. , & Topaz, M. (2022). Factors associated with poor self‐management documented in home health care narrative notes for patients with heart failure. Heart & Lung, 55, 148–154. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, H. W. , Kao, C. W. , Lin, W. S. , & Chang, Y. C. (2019). Factors affecting self‐care maintenance and Management in Patients with Heart Failure: Testing a path model. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 34(4), 297–305. 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X. , Zhou, X. , Ma, L. L. , Sun, T. W. , Bishop, L. , Gardiner, F. W. , & Wang, L. (2019). A nurse‐led structured education program improves self‐management skills and reduces hospital readmissions in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized and controlled trial in China. Rural and Remote Health, 19(2), 5270. 10.22605/rrh5270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H. , Jayasena, R. , Chen, S. H. , Maiorana, A. , Dowling, A. , Layland, J. , Good, N. , Karunanithi, M. , & Edwards, I. (2020). The effects of Telemonitoring on patient compliance with self‐management recommendations and outcomes of the innovative Telemonitoring enhanced care program for chronic heart failure: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(7), e17559. 10.2196/17559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Dinh, T. T. , Bonner, A. , Clark, R. , Ramsbotham, J. , & Hines, S. (2016). The effectiveness of the teach‐back method on adherence and self‐management in health education for people with chronic disease: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 14(1), 210–247. 10.11124/jbisrir-2016-2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo, S. , Moser, D. K. , Lennie, T. A. , Fischer, M. , Kim, J. S. , Lee, M. , Walsh, M. N. , & Ounpraseuth, S. (2018). Changes in heart failure symptoms are associated with changes in health‐related quality of life over 12 months in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 1, 460–466. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herber, O. R. , Kastaun, S. , Wilm, S. , & Barroso, J. (2019). From qualitative meta‐summary to qualitative meta‐synthesis: Introducing a new situation‐specific theory of barriers and facilitators for self‐Care in Patients with Heart Failure. Qualitative Health Research, 29(1), 96–106. 10.1177/1049732318800290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopewell, S. , Clarke, M. , Lefebvre, C. , & Scherer, R. (2007). Handsearching versus electronic searching to identify reports of randomized trials. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2007(2), Mr000001. 10.1002/14651858.MR000001.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough, C. B. (1989). Strategies for theory construction nursing. Nurse Education Today, 9(5), 360. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S. (2020). Summary of China cardiovascular health and disease report 2020. China Circulation Journal, 36(6), 25. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2021.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Im, E. O. (2005). Development of situation‐specific theories: An integrative approach. Ans Advances in Nursing Science, 28(2), 137–151. 10.1097/00012272-200504000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im, E. O. (2014). The status quo of situation‐specific theories. Research & Theory for Nursing Practice, 28(4), 278–298. 10.1891/1541-6577.28.4.278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im, E. O. (2018). Theory development strategies for middle‐range theories. Adv Nursing Science, 41(3), 275–292. 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im, E. O. , & Meleis, A. I. (1999). Situation‐specific theories: Philosophical roots, properties, and approach. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 22(2), 11–24. 10.1097/00012272-199912000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irani, E. , Moore, S. E. , Hickman, R. L. , Dolansky, M. A. , Josephson, R. A. , & Hughes, J. W. (2019). The contribution of living arrangements, social support, and self‐efficacy to self‐management behaviors among individuals with heart failure: A path analysis. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 34(4), 319–326. 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y. , & Peng, Y. (2022). The development of a situation‐specific nurse‐led culturally tailored self‐management theory for Chinese patients with heart failure. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 33(1), 6–15. 10.1177/10436596211023973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, R. E. , Majothi, S. , Heneghan, N. R. , Blissett, D. B. , Riley, R. D. , Sitch, A. J. , Price, M. J. , Bates, E. J. , Turner, A. M. , Bayliss, S. , Moore, D. , Singh, S. , Adab, P. , Fitzmaurice, D. A. , Jowett, S. , & Jolly, K. (2015). Supported self‐management for patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): An evidence synthesis and economic analysis. Health Technology Assessment, 19(36), 1–516. 10.3310/hta19360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademian, Z. , Kazemi Ara, F. , & Gholamzadeh, S. (2020). The effect of self care education based on Orem's nursing theory on quality of life and self‐efficacy in patients with hypertension: A quasi‐experimental study. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery, 8(2), 140–149. 10.30476/ijcbnm.2020.81690.0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. , Zhang, Y. , Liu, H. J. , Song, T. , & Wang, S. (2022). Influence of health education based on IMB on prognosis and self‐management behavior of patients with chronic heart failure. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2022, 8517802. 10.1155/2022/8517802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lovell, J. , Pham, T. , Noaman, S. Q. , Davis, M. C. , Johnson, M. , & Ibrahim, J. E. (2019). Self‐management of heart failure in dementia and cognitive impairment: A systematic review. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 19(1), 99. 10.1186/s12872-019-1077-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, M. , & Wills, E. M. (2019). Theory basis for nursing (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Meleis, A. I. (2017). Theoretical nursing:Development and progress (6th ed.). Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, I. L. (2006). Strategies for theory construction in nursing 4th edition. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 20(6), 308. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, M. C. , Wingham, J. , Dalal, H. M. , & Taylor, R. S. (2019). Involving caregivers in self‐management interventions for patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(12), 3331–3345. 10.1111/jan.14172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onkman, N. H. , Westland, H. , Groenwold, R. H. , Ågren, S. , Atienza, F. , Blue, L. , Bruggink‐André de la Porte, P. W. , DeWalt, D. A. , Hebert, P. L. , Heisler, M. , Jaarsma, T. , Kempen, G. I. , Leventhal, M. E. , Lok, D. J. , Mårtensson, J. , Muñiz, J. , Otsu, H. , Peters‐Klimm, F. , Rich, M. W. , … Hoes, A. W. (2016). Do self‐management interventions work in patients with heart failure? An individual patient data meta‐analysis. Circulation an Official Journal of the American Heart Association, 133(12), 1189–1198. 10.1161/circulationaha.115.018006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway, M. R. , Sadler, L. S. , Dixon, J. , & Slade, A. (2014). Parental reflective functioning: Analysis and promotion of the concept for paediatric nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(23–24), 3490–3500. 10.1111/jocn.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Shamseer, L. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Brennan, S. E. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Li, T. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McDonald, S. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed), 74(9), 790–799. 10.1016/j.rec.2021.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. , Godfrey, C. , Mcinerney, P. , Soares, C. B. , & Parker, D. (2015). Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. In The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual. the Joanna Briggs Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski, P. , Voors, A. A. , Anker, S. D. , Bueno, H. , Cleland, J. G. , Coats, A. J. , Falk, V. , González‐Juanatey, J. R. , Harjola, V. P. , Jankowska, E. A. , Jessup, M. , Linde, C. , Nihoyannopoulos, P. , Parissis, J. T. , Pieske, B. , Riley, J. P. , Rosano, G. M. C. , Ruilope, L. M. , Ruschitzka, F. , … ESC Scientific Document Group . (2016). 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. European Journal of Heart Failure, 18(8), 891–975. 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B. , Carlson, B. , & Glaser, D. (2000). Development and testing of a clinical tool measuring self‐management of heart failure. Heart & Lung, 29(1), 4–15. 10.1016/s0147-9563(00)90033-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B. , & Dickson, V. V. (2008). A situation‐specific theory of heart failure self‐care. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 23(3), 190–196. 10.1097/01.Jcn.0000305091.35259.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B. , Dickson, V. V. , & Faulkner, K. M. (2016). The situation‐specific theory of heart failure self‐care: Revised and updated. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 31(3), 226–235. 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B. , Dickson, V. V. , & Vellone, E. (2022). The situation‐specific theory of heart failure self‐care: An update on the problem, person, and environmental factors influencing heart failure self‐care. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 37(6), 515–529. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B. , Jaarsma, T. , & Strömberg, A. (2012). A middle‐range theory of self‐care of chronic illness. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 35(3), 194–204. 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318261b1ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B. , Lee, C. S. , Albert, N. , Lennie, T. , Chung, M. , Song, E. K. , Bentley, B. , Heo, S. , Worrall‐Carter, L. , & Moser, D. K. (2011). From novice to expert: Confidence and activity status determine heart failure self‐care performance. Nursing Research, 60(2), 132–138. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31820978ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J. , Stevenson, F. , Lau, R. , & Murray, E. (2016). Factors that influence the implementation of e‐health: A systematic review of systematic reviews (an update). Implementation Science, 11(1), 146. 10.1186/s13012-016-0510-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfield, C. , Dickson, K. , & Bangpan, M. (2016). Exploring issues in the conduct of website searching and other online sources for systematic reviews: How can we be systematic? Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 191. 10.1186/s13643-016-0371-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie, E. , Zarin, W. , O'Brien, K. K. , Colquhoun, H. , Levac, D. , Moher, D. , Peters, M. D. J. , Horsley, T. , Weeks, L. , Hempel, S. , Akl, E. A. , Chang, C. , McGowan, J. , Stewart, L. , Hartling, L. , Aldcroft, A. , Wilson, M. G. , Garritty, C. , … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellone, E. , Riegel, B. , & Alvaro, R. (2019). A situation‐specific theory of caregiver contributions to heart failure self‐care. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 34(2), 166–173. 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L. O. , & Avant, K. (2011). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Wingham, J. , Harding, G. , Britten, N. , & Dalal, H. (2014). Heart failure patients' attitudes, beliefs, expectations and experiences of self‐management strategies: A qualitative synthesis. Chronic Illness, 10(2), 135–154. 10.1177/1742395313502993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q. , Chen, C. , Zhang, J. , Ye, Y. , & Fan, X. (2021). Effects of self‐management interventions on heart failure: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials ‐ reprint. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 116, 103909. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable—no new data are generated.