Abstract

The tolQRA genes have been recently identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. In this study, we examined the effect of iron and temperature on tolQRA expression. A promoterless lacZ gene was introduced downstream of plasmid-encoded tolQ and tolA, and expression was monitored by measuring β-galactosidase activity of cultures. Addition of 25 μM FeCl3 to the culture medium reduced tolQRA expression by 50 to 60% in PAO but by only 25% in the fur mutant PAO A4. Northern hybridization analysis revealed that iron regulation occurs at the level of transcription and involves the P. aeruginosa ferric uptake regulator (Fur). Primer extension analysis was used to identify the proposed transcriptional start site of tolA. Although a putative Fur box was identified 20 bp upstream of the proposed start site, purified Fur did not bind to the tolA or tolQR promoter regions in an in vitro gel retardation assay. Therefore, iron regulation of the tol genes appears to involve an intermediate regulatory gene. Expression of tolQR and tolA was optimal at 37°C and was reduced by 40 to 50% when cultures were grown at either 42 or 25°C. Growth in high-iron medium at 25°C further reduced tolQR and tolA expression.

The outer membrane (OM) of gram-negative bacteria consists of an inner monolayer of phospholipids linked to an outer leaflet predominantly composed of negatively charged lipopolysaccharide molecules which are noncovalently bridged by divalent cations. In addition, a certain number of porins form nonselective channels allowing free diffusion of small hydrophilic molecules (<700 Da), while more selective porins facilitate diffusion of particular nutrients (18). This overall structure enables the OM to exclude potentially harmful molecules and to serve as a selective permeability barrier.

S-type pyocins and type A colicins are bacterial toxins which exert their lethal activity upon intracellular targets (26, 28). These bacteriocins are bulky molecules (5, 26) exceeding the diffusion limit of the OM and consequently cannot freely diffuse to the cell periplasm. Escherichia coli type A colicins parasitize the high-affinity OM ferric siderophore receptors and the inner membrane proteins TolQRA in order to circumvent the OM permeability barrier and gain entry into bacterial cells (5, 28). The E. coli TolQRA proteins are also involved in maintaining the integrity of the E. coli cell envelope, and they have been proposed to form a structural bridge between the inner and outer membranes in concert with the tolB and pal gene products (3, 28).

The tolQRA homologs have been identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and shown to be involved in pyocin transport (8). The P. aeruginosa tolQ and tolR genes were found to be cotranscribed as a 1.5-kb transcript, while transcription of the 1.2-kb tolA mRNA was shown to occur from its own promoter (8). Interestingly, a P. aeruginosa DNA fragment encoding an open reading frame (ORF) (pig6) exhibiting a high degree of homology to E. coli orf1, which is located upstream of E. coli tolQ, was isolated as an iron-regulated gene directly bound by the P. aeruginosa ferric uptake regulator (Fur) (21). The ORF immediately downstream of pig6 had homology to E. coli tolQ. These studies suggest that tolQ expression as well as orf1 (pig6) might be regulated by Fur in P. aeruginosa.

There are no reports which suggest that in E. coli the tol genes may be iron regulated by Fur; the only environmental condition reported to influence expression of the E. coli tol genes has been temperature. Clavel et al. (6) demonstrated that expression of chromosomal tolR::lacZ and tolA::lacZ operon fusions was approximately threefold higher when cells were grown at temperatures lower than 37°C. The investigators were able to correlate tol expression with capsule synthesis. The objectives of the present study were to determine if expression of the tolQRA genes in P. aeruginosa is regulated by either iron or temperature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and β-galactosidase assays.

Strains and plasmids described in this study are listed in Table 1. For β-galactosidase assays, cultures were grown in either LB broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) or TSBDC broth (22) supplemented in some instances with either 400 μg of ethylenediamine di(o-hydroxy)phenylacetic acid (EDDHA) per ml or 50 μM FeCl3. The initial iron concentration of TSBDC has previously been determined to be 1 μM (22). Unless indicated otherwise, cultures were grown at 37°C at 200 rpm to mid-log phase of growth (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.5). This OD represented mid-log phase of growth in all medium conditions used. β-Galactosidase assays were performed as previously described and are expressed in Miller units (17). Values represent the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments. All cultures were assayed during mid-log phase at the same OD. No growth effects on β-galactosidase activity were observed during mid-log phase of growth (data not shown). No differences in β-galactosidase activity of tolQR or tolA::lacZ fusions were observed between LB and TSBDC broth supplemented with 400 μg of EDDHA per ml (compare Fig. 1 and 3). For RNA isolation, cultures were grown in TSBDC medium as parallel Northern hybridization experiments were performed with P. aeruginosa toxA as a control iron-regulated transcript (data not shown) (16). All reagents and media were prepared with H2O purified by the Milli Q system (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). Antibiotics were added to the growth medium at the following concentrations where appropriate: for E. coli, 15 μg of gentamicin or tetracycline per ml; for P. aeruginosa, 200 μg of gentamicin or 250 μg of tetracycline per ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA recA1 hsdR17 deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco BRL |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO | Prototroph | 12 |

| PAO A2 | fur mutant of PAO | 1 |

| PAO A4 | fur mutant of PAO | 1 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEL3.5 | Ampr, pNOT19 carrying 3.5-kb SphI-PstI fragment (tolQRA) | 8 |

| pPA3.5RK | Tcr, pRK415 carrying 3.5-kb SphI-PstI fragment (tolQRA) | 8 |

| pRKAz | Tcr, Gmr, pPA3.5RK with 4.3-kb SalI lacZ-Gmr cassette in XhoI site of tolA, tolA::lacZ operon fusion | 8 |

| pRKQz | Tcr, Gmr, pPA3.5RK with 4.3-kb BamHI lacZ-Gmr cassette in BglII site of tolQ, tolQR::lacZ operon fusion | 8 |

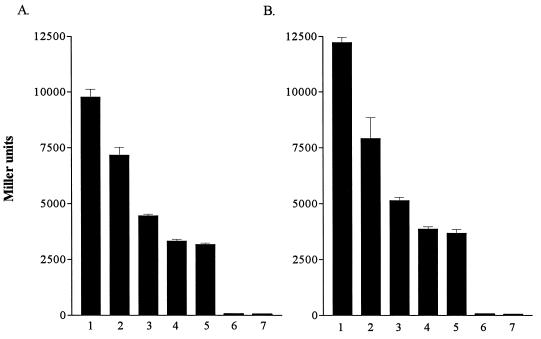

FIG. 1.

Effects of iron on expression of plasmid-encoded tolA::lacZ (A) and tolQR::lacZ (B) operon fusions in PAO. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed in Miller units. The plasmid control (pPA3.5RK) is represented in lanes 6 and 7 in both panels. Values represent the mean (± standard deviation) of triplicate experiments. Strains were grown in LB broth supplemented with 400 μg of EDDHA per ml (lanes 1 and 6), LB broth (lanes 2), and LB broth supplemented with 10 μM (lanes 3), 25 μM (lanes 4), or 100 μM (lanes 5 and 7) FeCl3. A significant difference in β-galactosidase activity was observed between lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4 (P ≤ 0.05, Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction). Addition of 100 μM FeCl3 did not result in a significant decrease in β-galactosidase activity from that noted with 25 μM added FeCl3.

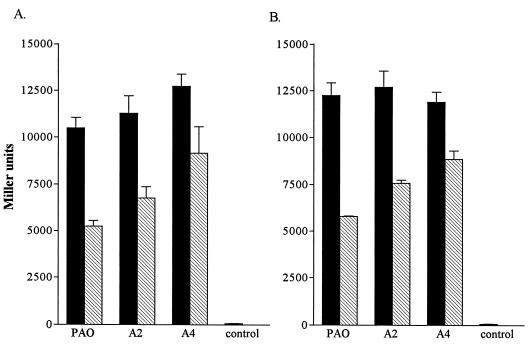

FIG. 3.

Effects of iron on expression of plasmid-encoded tolA::lacZ (A) and tolQR::lacZ (B) operon fusions in P. aeruginosa fur mutants. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed in Miller units. The plasmid control (pPA3.5RK) is represented in both panels. Values represent the mean (± standard deviation) of triplicate experiments. Cultures were grown in LB broth supplemented with 400 μg of EDDHA per ml (closed bars) or 50 μM FeCl3 (hatched bars). A significant decrease in β-galactosidase activity was observed in all strains with the addition of FeCl3 (P ≤ 0.05, Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction).

DNA probes.

DNA fragments used as probes in Northern hybridization experiments were purified by using Gene-Clean II (Bio/Can Scientific, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA fragments were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham Life Sciences, Oakville, Ontario, Canada), using an oligolabeling kit (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Baie d’Urfe, Quebec, Canada) as recommended by the manufacturer. Synthetic oligonucleotides used in primer extension experiments were end labeled with [γ-32P]dATP (Amersham Life Sciences), using T4 phosphorylase nucleotide kinase (Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) as recommended by the manufacturer.

RNA isolation and Northern hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated by using a hot-phenol extraction procedure (27) from 10-ml cultures at an OD600 of 0.5 or 1.0. Aliquots of 15 μg of total RNA were denatured at 55°C for 15 min in the presence of 2 M formaldehyde and 50% formamide, and duplicate samples of RNA were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel containing 2 M formaldehyde in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid buffer (24). After electrophoresis, half of the agarose gel was stained with ethidium bromide and the RNA was visualized under UV light. The other half was transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and baked for 2 h at 80°C, and hybridization was performed overnight at 65°C in 15 ml of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–1 M NaCl–10% dextran sulfate–0.1 mg of salmon sperm DNA per ml. The membranes were washed twice for 15 min each time at room temperature in 1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS and twice for 15 min at 65°C in 0.25× SSC–0.1% SDS. The membranes were dried and autoradiographed with Kodak X-Omat AR 100 film.

Nucleotide sequencing and primer extension experiments.

Sequencing was performed by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (25) with T7 DNA polymerase (Sequenase 2.0 kit; United States Biochemical Corp., Oakville, Ontario, Canada), [35S]dATP (Amersham Life Sciences), and a synthetic oligonucleotide primer (5′-GGCCAGAAATAACTCTCGG-3′) as recommended by the manufacturer. Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (Life Technologies) was added after termination of the sequencing-labeling reactions to resolve ambiguities in GC-rich templates (13).

Primer extension reactions using SuperScript II RNase H reverse transcriptase (RT; Gibco BRL Canada, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) were performed as recommended by the manufacturer. RNA samples were denatured for 15 min at 95°C and then placed on ice. Thirty-five micrograms of denatured RNA was mixed with 106 cpm of end-labeled synthetic oligonucleotide primer (5′-GGCCAGAAATAACTCTCGG-3′) in a final volume of 12.5 μl. Annealing performed at 65°C for 10 min was followed by a 1-min incubation step at room temperature, after which samples were cooled on ice. The annealed primer was subsequently extended at 42°C for 60 min in the presence of 30 U of RNAsin, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, and 200 U of RT. The enzyme was heat inactivated for 10 min at 75°C, and the samples were electrophoresed.

DNA mobility shift assays.

DNA mobility shift assays were performed as described by Ochsner et al. (20), with minor modifications. DNA fragments were labeled as above and mixed with 20 μl of binding buffer, composed of 20 mM Tris borate (pH 7.5), 40 mM KCl, 0.1 mM MnSO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 50 μg of poly(dI-dC) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml, and 10% glycerol. Fur protein was added to give final concentrations ranging from 0 to 1,000 nM, and the mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. A 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in running buffer (20 mM Tris borate, 0.1 mM MnSO4) was prerun for 10 min at 200 V and loaded with 10 μl of the binding reaction mixture. The gel was electrophoresed at 90 V for 4 h at 4°C, dried, and autoradiographed. A DNA fragment containing a synthetic Fur box consensus sequence was used as a positive control (20).

RESULTS

Effect of iron on expression of the tolQRA genes.

To determine if expression of the tol genes is iron regulated, strain PAO harboring pRKAz (tolA::lacZ) or pRKQz (tolQR::lacZ) was grown in LB broth supplemented either with 400 μg of EDDHA per ml (low iron) or with various concentrations of FeCl3 to mid-log phase of growth (A600 = 0.5), and the β-galactosidase activity was determined. β-Galactosidase activity was a direct measure of tolQR and tolA expression since the lacZ gene is under the transcriptional control of the tolQR or tolA promoter (8). tolQR and tolA expression was highest from cultures in low-iron medium (Fig. 1A and B, lanes 1). A 21% decrease in expression of tolA (Fig. 1A, lane 2) and an 18% decrease in expression of tolQR (Fig. 1B, lane 2) were observed when cells were grown in LB broth without EDDHA. Addition of 10 μM FeCl3 resulted in a 51% reduction in expression of tolA (Fig. 1A, lane 3) and a 47% reduction in expression of tolQR (Fig. 1B, lane 3), while addition of 25 μM FeCl3 decreased expression of tolA by 63% (Fig. 1A, lane 4) and tolQR by 60% (Fig. 1B, lane 4). Growth in the presence of higher concentrations of iron did not further reduce tolQR or tolA expression (Fig. 1A and B, lanes 5).

To confirm that the effect of iron on expression of tolQR was due to regulation at the level of transcription, total RNA isolated from PAO grown under low- or high-iron conditions was analyzed by Northern hybridization using probes specific for tolQ. The 1.5-kb tolQR transcript was present in much greater amounts when cells were grown in low-iron medium than when they were grown under high-iron conditions (data not shown). As the 1.2-kb tolA mRNA has been previously shown to be detected only in cells harboring plasmid-encoded tolQRA, presumably due to a low level of transcription (8), total RNA was isolated from PAO(pPA3.5RK) and analyzed as described above, using a probe specific for tolA. The 1.2-kb tolA transcript was also present in much greater amounts when cells were grown in low-iron medium than when they were grown under high-iron conditions. These data demonstrate that tolQR and tolA are iron regulated at the level of transcription and that the plasmid-encoded lacZ fusions are representative of expression of the chromosomally encoded tolQRA genes.

Effect of Fur on the expression of tolQRA.

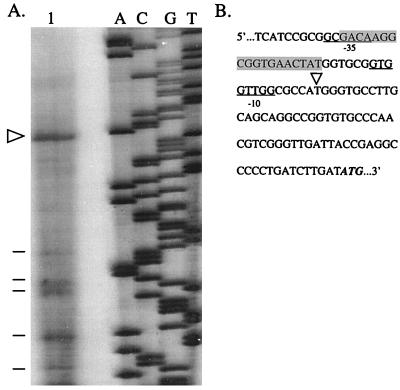

Total RNA isolated from PAO(pPA3.5RK) was used in primer extension experiments with RT and an oligonucleotide primer (5′-GGCCAGAAATAACTCTCGG-3′) complementary to the tolA coding strand and located 25 bp downstream of the tolA predicted translational start codon (8). Figure 2A shows the primer extended with RT (lane 1). The size of the product suggests that transcription begins at a thymine residue located 65 bases upstream of the predicted translational start codon of tolA (Fig. 2). RT has a tendency to stop or pause in regions of RNA exhibiting a high degree of secondary structures (24), and such prematurely aborted extension products can be observed (Fig. 2A, lane 1). A potential Fur box (9-of-19-bp homology to the consensus sequence) was observed 20 bases upstream of the proposed transcriptional start site of tolA (Fig. 2B). Primer extension experiments designed to determine the transcriptional start site of tolQ yielded ambiguous results, resulting in pausing/stopping of RT along the mRNA strand (data not shown), and were not investigated further.

FIG. 2.

Primer extension analysis of tolA mRNA. (A) Radioactively labeled oligonucleotide primer (5′-GGCCAGAAATAACTCTCGG-3′) extended with RT by using total RNA isolated from PAO(pPA3.5RK) (lane 1) and nucleotide sequence analysis of tolA performed with Sequenase 2.0, a synthetic oligonucleotide primer (5′-GGCCAGAAATAACTCTCGG-3′), and plasmid pEL3.5 (lanes A, C, G, and T). Arrowhead, proposed tolA transcriptional start site; lines, prematurely aborted extension products. The autoradiogram was turned over to represent the tolA coding strand and scanned with a Hewlett Packard Scan Jet 4c and Hewlett Packard Deskscan II software (Hewlett Packard Co.). (B) DNA sequence of the region upstream of the tolA predicted translational start codon (boldface and italic). Arrowhead, proposed tolA transcriptional start site; underlined bases, putative −35 and −10 promoter regions; shaded bases, putative Fur box.

To examine the possible role of Fur in iron regulation of the tolQRA genes, plasmids pRKAz and pRKQz were introduced into two P. aeruginosa strains carrying mutations in the fur gene: PAO A2 and PAO A4 (1). The effect of fur mutations on expression of the tol genes was examined by determining the β-galactosidase activity of cells grown under low- or high-iron conditions. Growth of PAO in high-iron medium resulted in a 50% decrease in tolQR and tolA expression compared to expression in low-iron medium (Fig. 3). In PAO A2 and PAO A4, addition of iron to the medium did not decrease expression of tolQR or tolA to the same extent as in PAO. β-Galactosidase activity was decreased by 40% in PAO A2 and only 25% in PAO A4. The effect of iron on tolQR and tolA expression in PAO A4 was also examined by using Northern hybridization (data not shown). The tolQR and tolA transcripts were produced in greater amounts in PAO A4 than in PAO when cultures were grown in high-iron medium.

To determine if Fur directly regulates tolQR and tolA expression, the ability of purified P. aeruginosa Fur to bind the promoter regions of tolQR and tolA was examined in a gel retardation assay. A 342-bp RrsII-AccI fragment containing the promoter region of tolQ and a 420-bp SalI-PvuII fragment upstream of tolA were examined for the ability to bind P. aeruginosa Fur. There was no difference in the mobility of these DNA fragments in the gel retardation assay even at Fur concentrations up to 1 μM. A positive control DNA fragment containing a synthetic Fur box (20) did show decreased mobility when incubated with Fur in this assay, confirming the activity of the Fur protein used (data not shown).

Effect of temperature on expression of tolQRA.

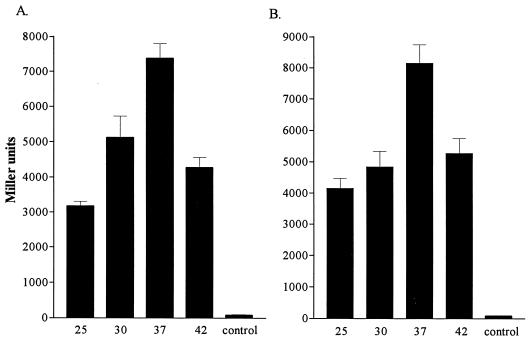

tolQRA expression in E. coli has been previously shown to be temperature dependent (6). To determine if expression of the P. aeruginosa homologs is also regulated by temperature, we determined the β-galactosidase activity of PAO cultures harboring pRKAz or pRKQz grown at different temperatures during the same stages of growth. Expression of the tol genes was optimal at 37°C, and increasing the temperature of growth to 42°C resulted in a 40% reduction in tol expression during mid-log phase of growth (Fig. 4). Expression of the tol genes was also approximately 30 to 40% lower when cells were grown at 30°C compared to 37°C. Growth at 25°C reduced expression of tolA by 57% (Fig. 4A) and expression of tolQR by 49% (Fig. 4B) compared to expression at 37°C. Unlike the E. coli tol genes, which are optimally expressed at 25°C (6), tol expression in P. aeruginosa is optimal at 37°C. Varying the growth temperature had no effect on expression of the P. aeruginosa tol::lacZ fusions in E. coli (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effects of temperature on expression of plasmid-encoded tolA::lacZ (A) and tolQR::lacZ (B) operon fusions in PAO. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed in Miller units. The plasmid control (pPA3.5RK) is represented in both panels. Values represent the mean (± standard deviation) of triplicate experiments. Strains were grown in LB broth at 25°C (25), 30°C (30), 37°C (37 and control), or 42°C (42). A significant decrease in β-galactosidase activity was observed when strains were grown at 25, 30, and 42°C (P ≤ 0.05, Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction).

To determine if temperature and iron supplementation could have a synergistic effect and completely turn off expression of the tol genes, we determined the β-galactosidase activity of PAO cultures carrying pRKAz or pRKQz grown at either 25 or 37°C under low- or high-iron conditions. Growth at 25°C in high-iron medium resulted in approximately 75% reductions in tolA and tolQR expression compared to expression at 37°C in low-iron medium (data not shown). Although the combination of iron and temperature reduces the expression of tolQR and tolA to lower levels, it does not completely repress expression of these genes.

DISCUSSION

Plasmid-encoded tolQR::lacZ or tolA::lacZ operon fusions were used to demonstrate that expression of P. aeruginosa tolQR and tolA is regulated by iron and temperature. PAO(pRKAz) and PAO(pRKQz) exhibited no differences in pyocin sensitivity compared to PAO(pRK415), indicating that the plasmid-encoded copies of the tol genes did not have a marked effect on membrane integrity (data not shown). Omission of the iron-chelating agent EDDHA from the growth media is sufficient to reduce the β-galactosidase activity of PAO(pRKAz) and PAO(pRKQz) by 20%, and the addition of increasing concentrations of iron further decreases the enzymatic activity. The fur gene product has previously been shown to act as a global modulator of iron-regulated genes in P. aeruginosa (21). It was therefore not surprising to discover that iron regulation of tol expression occurs at the level of transcription and was altered in fur mutants of P. aeruginosa. A potential Fur box (9-of-19-bp homology to the consensus sequence) was identified 20 bases upstream of the proposed transcriptional start site of tolA (Fig. 2B). Promoter regions of iron-regulated genes generally show homology to the Fur box consensus sequence with a 13- to 17-bp match (14); however, sequences exhibiting homology of only 10 to 11 bp to the Fur-binding consensus sequence have been identified as being directly bound by the P. aeruginosa Fur (21). Purified Fur, however, was unable to bind to either tolQR or tolA promoter region, suggesting that perhaps 10 bp is the minimum homology necessary.

Since Fur does not bind directly, it appears that Fur mediates iron regulation of the tol genes through an intermediate transcriptional regulator. Expression of the intermediate activator would be directly repressed at the level of transcription by Fur-Fe2+. Under conditions of iron starvation, repression by Fur would be relieved and the activator would be expressed, which in turn would activate transcription of the tol genes. Such a hierarchical organization of iron regulation by Fur has been reported in P. aeruginosa for expression of the ferripyochelin receptor, FptA, and pyochelin through the activator PchR (10, 11), and for production of pyoverdine (7) and exotoxin A (19) through the alternate sigma factor PvdS. Fur has previously been shown to bind to an ORF (orf1) of unknown function immediately upstream of tolQ (21). It is possible that this gene is involved in the intermediate regulation of tolQRA, although it exhibits no homology to known regulatory genes. E. coli Fur does not mediate iron repression of P. aeruginosa tol::lacZ expression, and β-galactosidase activity is actually increased when cultures are grown in iron-supplemented medium (data not shown). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that an intermediate transcriptional regulator might be involved, as this gene would presumably be absent in E. coli.

The iron regulation of tolA appears to be similar to that of P. aeruginosa tonB (23), a similar protein which is required for siderophore-mediated iron transport. The exbB and exbD homologs, which are functionally related to tolQ and tolR, respectively, in E. coli (4), have not yet been identified in P. aeruginosa, and so their iron regulation has not been examined. Exotoxin A and siderophore production in P. aeruginosa are more tightly regulated by iron than either the tol or tonB gene (1, 2, 23). Yields of exotoxin A and siderophores are generally decreased by approximately 90% in cultures grown in high-iron medium. Because of their possible role in maintaining membrane structure, it would likely not be possible to decrease expression of tolQRA to the same extent as extracellular factors.

The PAO A2 and A4 mutants have a mutation in the same amino acid residue resulting in a change of His-86 to Arg and Tyr, respectively (1). The mutation in A4 has previously been shown to have a greater effect on the binding ability of Fur. For example, pyoverdine yields are decreased by 66% in PAO A2 grown at 37°C in 50 μM iron compared to growth in 0 μM iron, whereas yields of pyoverdine are decreased by only 25% in PAO A4 in the same conditions (1). Purified Fur from PAO A4 was shown to have reduced binding activity to the Fur box of the pvdS promoter compared to purified Fur from PAO A2 (1). Our data are consistent with those of Barton et al. (1) in that iron regulation of tolQRA expression was less in PAO A4 than in PAO A2.

Clavel et al. (6) demonstrated that expression of chromosomal E. coli tolR::lacZ and tolA::lacZ operon fusions was approximately threefold higher when cells were grown at temperatures lower than 37°C. These investigators determined that this increase in tol expression was mediated by the RcsC transcriptional regulator of E. coli capsular polysaccharide colanic acid. A decrease in tol expression correlated with an increase in capsule synthesis, which might serve to protect the cell from increased sensitivity to deleterious agents as a result of the tol mutations.

In P. aeruginosa the optimal temperature of expression for tolQRA was determined to be 37°C. There was no difference in expression of the tol::lacZ fusions in E. coli, which suggests that there may be a specific regulatory factor present in P. aeruginosa involved in the temperature regulation of tolQRA. Pyoverdin and exotoxin A are produced in greater yields at 25 to 27°C (1) and 32°C (15), respectively. Therefore, there does not appear to be a consistent optimal temperature for expression of iron-regulated genes in P. aeruginosa. Factors mediating temperature-dependent expression of genes have not yet been identified in this organism.

In conclusion, expression of P. aeruginosa tolQR and tolA is iron regulated at the level of transcription, and this iron regulation may involve Fur in addition to an intermediate regulator. Identification of regulators involved in modulating tol expression in response to environmental cues may yield important information on the role(s) of the tolQRA gene products in P. aeruginosa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

We thank M. Vasil, University of Colorado, for the PAO fur mutants and the purified Fur protein. Excellent technical assistance was provided by Patricia Darling.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barton H A, Johnson Z, Cox C D, Vasil A I, Vasil M L. Ferric uptake regulator mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with distinct alterations in the iron-dependent repression of exotoxin A and siderophores in aerobic and microaerobic environments. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1001–1017. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.381426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorn M J, Sokol P A, Iglewski B H. Influence of iron on yields of extracellular products in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cultures. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:193–200. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.1.193-200.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouveret E, Derouiche R, Rigal A, Lloubes R, Lazdunski C, Benedetti H. Peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein-TolB interaction. A possible key to explaining the formation of contact sites between the inner and outer membranes of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11071–11077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun V, Herrmann C. Evolutionary relationship of uptake systems for biopolymers in Escherichia coli: cross-complementation between the TonB-ExbB-ExbD and the TolA-TolQ-TolR proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun V, Pilsl H, Groß P. Colicins: structures, modes of action, transfer through membranes, and evolution. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:199–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00248693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clavel T, Lazzaroni J C, Vianney A, Portalier R. Expression of the tolQRA genes of Escherichia coli K-12 is controlled by the RcsC sensor protein involved in capsule synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:19–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.343880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunliffe H E, Merriman T R, Lamont I A. Cloning and characterization of pvdS, a gene required for pyoverdine synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: PvdS is probably an alternative sigma factor. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2744–2750. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2744-2750.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis J J, Lafontaine E R, Sokol P A. Identification and characterization of the tolQRA genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7059–7068. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7059-7068.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawley D K, McClure W R. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:2237–2255. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.8.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinrichs D E, Poole K. Cloning and sequence analysis of a gene (pchR) encoding an AraC family activator of pyochelin and ferripyochelin receptor synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5882–5889. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5882-5889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinrichs D E, Poole K. PchR, a regulator of ferripyochelin receptor gene (fptA) expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, functions both as an activator and as a repressor. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2586–2592. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2586-2592.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holloway B W, Romling U, Tummler B. Genomic mapping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Microbiology. 1994;140:2907–2929. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li M, Schweizer H P. Resolution of common DNA sequencing ambiguities of GC-rich DNA templates by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase without dGTP analogues. Focus. 1993;15:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litwin C M, Calderwood S B. Role of iron in regulation of virulence genes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:137–149. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu P V. Exotoxins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. I. Factors that influence the production of exotoxin A. J Infect Dis. 1973;128:506–513. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lory S. Effect of iron on accumulation of exotoxin A-specific mRNA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1451–1456. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1451-1456.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochsner U A, Johnson Z, Lamont I L, Cunliffe H E, Vasil M L. Exotoxin A production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires the iron-regulated pvdS gene encoding an alternative sigma factor. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1019–1028. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.481425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochsner U A, Vasil A I, Vasil M L. Role of the ferric uptake regulator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the regulation of siderophores and exotoxin A expression: purification and activity on iron-regulated promoters. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7194–7201. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7194-7201.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochsner U A, Vasil M L. Gene repression by the ferric uptake regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: cycle selection of iron-regulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4409–4414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohman D E, Sadoff J C, Iglewski B H. Toxin A-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO-103: isolation and characterization. Infect Immun. 1980;28:899–908. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.899-908.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole K, Zhao Q, Neshat S, Heinrichs D E, Dean C R. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa tonB gene encodes a novel TonB protein. Microbiology. 1996;142:1449–1458. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sano Y, Matsui M, Kobayashi M, Kageyama M. Pyocins S1 and S2, Bacteriocins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Silver S, Chakrabarty A M, Iglewski B H, Kaplan S, editors. Pseudomonas: biotransformations, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 352–358. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storey D G, Raivio T L, Frank D W, Wick M J, Kaye S, Iglewski B H. Effects of regB expression from the P1 and P2 promoters of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa regAB operon. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6033–6044. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6088-6094.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webster R E. The tol gene products and the import of macromolecules into Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1005–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]