Abstract

Membrane asymmetry means that the two sides of membrane are structurally, physically and functionally different. Membrane asymmetry is largely related to the lipid sidedness and particularly to compositional (lipid head and acyl group) and physical (lipid packing order, charge, hydration and H-bonding interactions) differences in the inner and outer leaflets of lipid bilayer. Chemically, structurally and conformationally different non-covalent bound lipid molecules are physically fluid and deformable and enable to interact dynamically to form transient arrangements with asymmetry both perpendicular and parallel to the plane of the lipid bilayer. Although biological membranes are almost universally asymmetric however the asymmetry is not absolute since only drastic difference in the number of lipids per leaflet is found and symmetric arrangements are possible. Asymmetry is thought to direct and influence many core biological functions by altering the membrane’s collective biochemical, biophysical and structural properties. Asymmetric transbilayer lipid distribution is found across all lipid classes, cells and near all endomembrane compartments. Why cell membranes are (a)symmetric and adopt almost exclusively highly entropically disfavored asymmetric state?

“The universe is asymmetric and I am persuaded that life, as it is known to us, is a direct result of the asymmetry of the universe or of its indirect consequences”

-Louis Pasteur

Introduction

Membrane asymmetry highlights vectorial nature of biological membrane which are generally envisioned as bilayer into which membrane lipids and proteins are asymmetrically embedded [1]. All biological membranes contain a spectrum of lipid enantiomeric and diastereomeric species with diverse molecular shape and differing in the number of acyl chain length, saturation state, head and backbone group composition, chirality, ionization and chelating properties. Lipid and protein constituents of living membrane are subject to a number of dynamic processes due to synthesis and turnover, function, phase separation and transition, transient compositional and physical arrangements with asymmetry both perpendicular and parallel to the plane of the lipid bilayer, moving through different organelles to their final destination.

The non-equilibrium thermodynamic state of the asymmetric membrane is maintained by the activity of ATP-dependent phospholipid flippases and energy-independent, inherently nonspecific scramblases which are able create or dissipate a transmembrane lipid asymmetry respectively. These proteins compensate for usually very slow spontaneous flip-flop of lipids across bilayer due to the existence of a thermodynamic barrier hindering this process. Biogenic membranes contain the enzymes that continuously synthesize and insert phospholipids specifically in one of the leaflets of the membrane. Thus theoretically lipid asymmetry in biogenic membranes can be generated primarily but transiently by selective synthesis of lipids on one side of the membrane.

The collection of minireviews encompasses both experimental and theoretical studies and novel findings that report on all aspects of the lipids spontaneous and facilitated transmembrane arrangements of lipids within single biological or artificial membrane and between intracellular membranes in eukaryotes and diderm bacteria with two-membraned envelope.

Scope for origin and maintenance of membrane asymmetry

I would like to highlight and manifest basic principles which guide one of the main capabilities and fundamental features of all biological membranes — (a)symmetry.

Transbilayer asymmetry is largely related to highly entropically disfavored unequal compositional headgroup and acyl asymmetries which should be actively maintained by the action of active (flippases) and ‘passive’ (scramblases) phospholipid translocators and facilitators.

An asymmetric membrane resides out of thermodynamic equilibrium however stochastic movement of lipids between bilayer leaflets would normally lead to an equilibrated symmetric distribution of membrane lipids which is entropically favored and can be achieved by the action of different scramblases.

Compositional and physical asymmetries are inherently linked. Due to permanent or transient asymmetric distribution of lipid head groups and acyl chain unsaturation, molecular (number of fatty acid, their length and saturation) and compositional asymmetry is closely associated with the physical asymmetry of the bilayer resulting in a less fluid, more tightly packed outer leaflet, and a more fluid, loosely packed inner leaflet in eukaryotic plasma membranes resulting in fluidity gradient across bilayer [2]. However, this phenomenon is mirrored in prokaryotic cytoplasmic membranes [3].

Compositional and physical transmembrane asymmetries and lateral heterogeneities causes imbalances in the two membrane leaflets, contributing to membrane spontaneous curvature [4].

Biological membranes are almost universally but not absolutely asymmetric: only drastic difference in the number of lipids of every lipid class is maintained in each bilayer leaflet.

Transmembrane and lateral phospholipid asymmetries are not absolute as it would be expected for integral membrane proteins. Transmembrane topology of integral membrane proteins is predominantly set at the time of their synthesis. It is generally thought that membrane proteins are absolutely asymmetric and adopt exactly the same orientation in the membrane despite the fact that membrane proteins with dual and dynamic topologies exist [5,6]. However current studies of membrane folding and topogenesis do not employ an asymmetric membranes and do not address the importance lipid asymmetry.

If asymmetric lipid distribution is settled within a genetically and structurally predefined range of possibilities given asymmetric membrane can be dispensable or necessary for cell viability or organelle optimal function.

Membrane protein functioning may require not only a particular lipid environment but also a particular lipid sidedness (e.g. transbilayer compositional, physical and charge asymmetries [7,8].

If asymmetry is indispensable for cell viability lipid sidedness provides lateral and transmembrane heterogeneity and contributes to optimal functioning of residing proteins and endomembrane compartments and influences, or even facilitates morphological changes via curvature-based bending and sorting of lipids as such as underlying raft assembly in living cells to compartmentalize cellular functions.

If asymmetry is dispensable for cell viability it may be difficult or even impossible to identify genetically the flippase candidates by searching for synthetic lethal interactions and loss of function mutations unless new cellular circumstances in stressed cells will be uncovered. However, the biochemical reconstitution and search for in vivo conditions which can modulate drastic changes in lipid asymmetry represent a very reasonable starting points.

Unidirectional lipid gradient across endomembrane compartments is maintained by counter-flow exchanges at interoganelle contact sites driven by lipid transfer proteins and lipid-synthesizing enzymes. This mechanism not only ensures continuous supply of desired lipid but also contributes to surveillance of uneven distributions of individual lipids among intracellular organelles and plasma membrane.

The term ‘lipid topogenesis’ (topography of lipid synthesis, translocation across and the sorting between intracellular membranes required to establish an asymmetric distribution) can be applied to biogenesis of lipids in double-membraned (diderm) bacteria.

‘Omnis membrana e membrana’

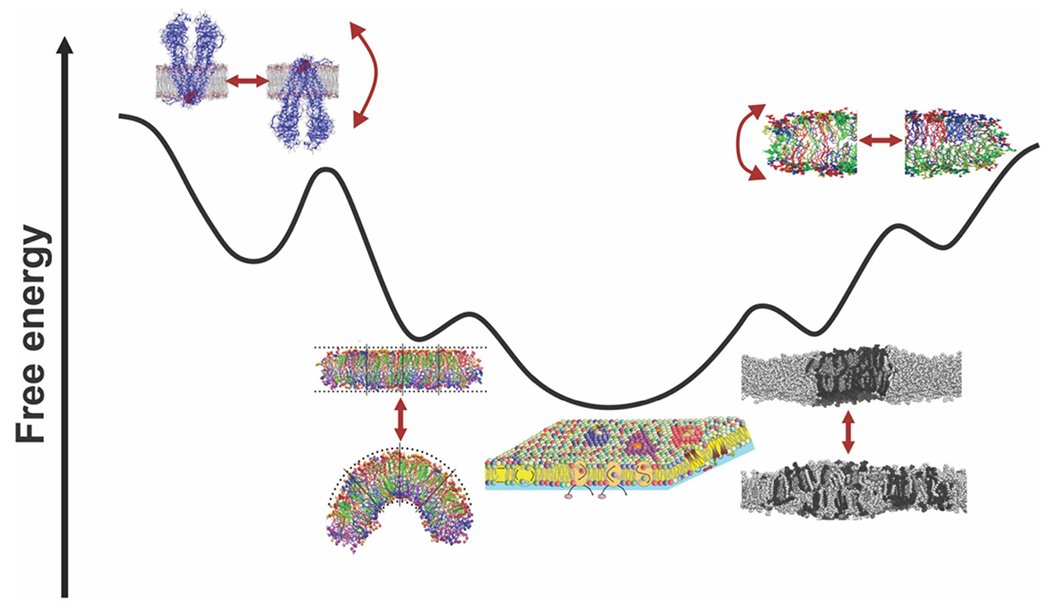

Since membrane proteins and lipids are amphiphilic molecules, the same structural constraints were reasonably applied to build a Fluid-mosaic membrane model which is based on thermodynamic equilibrium and hydrophobic matching principles of organization of membrane lipids and proteins [9]. However, this simplistic view is far from reality. Lipids and proteins in biological membranes are known to be highly heterogeneous laterally, transversally, in space and time thereby known to dynamically influence each other. Current dogma still states that membrane protein topological organization is determined at the time of initial membrane insertion and assembly due to the perceived high energy cost in flipping of folded hydrophilic domains through a lipid bilayer. Contrary to early assumptions about membranes some integral membrane proteins possess the capacity to reversibly reorient themselves during or after insertion if membrane phospholipid composition is changed or membrane is depolarized [6]. These findings contradict the Fluid-Mosaic Model. Although native single membrane component and supramolecular membrane structures are expected to reside in significantly lower free energy than non-native, the lipid and protein constituents of a living membrane appears to be far from being well equilibrated. Lipid and proteins of living membrane are subject to a number of dynamic processes due to synthesis, function, interorganelle membrane traffic and turnover. A membrane may maintain such non-equilibrium thermodynamic states by balancing transient disturbances caused by insertion of newly synthesized lipids and proteins, lateral movements of membrane components, gain and loss of transbilayer asymmetry supported by action of active (flippases) and ‘passive’ (scramblases) phospholipid translocators. Due to compositional and dynamic diversity of different membranes, local non-equilibrium conditions are likely attainable and should be considered for lateral or transmembrane lipid-protein rearrangements along with global equilibrium conditions (Figure 1). Obviously, both thermodynamic equilibrium and kinetic principles should serve as the sole mechanisms for creating and maintaining the dynamic asymmetric organization observed in the plasma membrane and endomembrane compartments. The structure, dynamics and stability of biological membranes are controlled by thermodynamic forces continuously shifting the system from equilibrium, leading to the formation or dissipation of non-equilibrium states separated by low or high activation energy barriers. This new concept proposes that lipid and protein molecules in biological membranes exist as metastable non-uniform, non-random but cooperative elements in transient non-thermodynamic equilibrium states with lateral and transversal compositional fluctuations. Changes in the lipid environment, lateral and transmembrane lipid and protein movements, transient lipid–protein interaction etc. can alter this energy landscape. Kinetic traps can also reflect transient trapping in local energy minima and time span for given membrane bound event. The heights of the transition energy barrier under a given set of physicochemical conditions determines the probabilities of a given membrane bound event which can occur at any time and in any membrane.

Figure 1. A Gibbs free energy landscape of living membrane structure and function.

Living membranes differ in lipids cooperating with embedded proteins during and after assembly on multiple time- and length scales in permanent and transient modes of interaction. Lipid diversity settled within a genetically and structurally predefined range of possibilities is necessary to generate asymmetric or symmetric, thin or thick cell membranes with either barrier or biogenic functions, enable membranes to deform, curve, bend and bulge, support the proper folding and activities of membrane proteins. Local enrichment of specific lipids can induce different curvatures and the formation of microdomains (rafts). Rafts exist in both the external and internal leaflets of the membrane, and overlap so that they are coupled functionally and structurally. Dynamic lipid bilayers adopt and re-adopt different lateral and transverse arrangements (reflected by re-shaping of free energy landscape) and reside in many local free dissipative (metastable) and non-dissipative or long-standing (kinetic traps) energy minimums resulting from numerous cooperative and non-cooperative interactions restricted and permitted by favorable thermodynamics. The conformational and transmembrane freedom and low activation energy barrier observed for flip-flopping membrane proteins is restricted to subset of membrane proteins and particular conditions and circumstances otherwise an enormous energy penalty is required to flip hydrophilic domains across the hydrophobic barrier of the membrane. These biochemical and structural rearrangements keep membrane system away from an overall thermodynamic equilibrium (bottom minifigure placed centrally). Adapted from Bogdanov, M. and Dowhan, W. ‘Functional roles of lipids in biological membranes’ Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes, 2021, Chapter 1, Pages 1–51. (Neale D. Ridgway and Roger S. McLeod., Eds) 7th Edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2021) with great respect to all authors (cited in this Chapter) whose figures were utilized to illustrate this scheme.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) residing enzymes synthesize the vast majority of lipid classes, and species which should be subsequently distributed between the leaflets of ER with still curious transmembrane lipid distribution and distribution among endomembrane compartments. Drin [10] describes how sophisticated networks composed of lipid transfer proteins and lipid-synthesizing enzymes regulate counter-flow exchanges at interoganelle contact sites to generate and maintain unidirectional lipid gradient in endomembrane compartments. Despite drastic stoichiometric difference metabolically driven dissipation of PI(4)P gradient at the ER/Golgi and ER/PM interfaces is required not only to supply the trans-Golgi and plasma membrane with sterol and PS respectively but also perfectly suited to sense an uneven distributions of individual lipids among intracellular organelles and plasma membrane.

Do symmetric biological membranes exist? Although it was known from in vitro experiment that asymmetric liposomal membranes have bending rigidities that are significantly higher than their symmetric counterparts [11]. However until new findings published recently and reviewed by Nagao and Umeda [12], the physiological meaning of this phenomenon was not known. Employing different vectorial lipid binding probes and clever SDS-digested freeze-fracture replica labeling (FRL) which does not require plasma membrane in the form of vesicles of uniform sidedness, it was demonstrated that constitutive scrambling of Drosophila plasma membrane lipids results in symmetric lipid distribution and extremally deformable membrane. This finding is in contrast with all other known highly asymmetric eukaryotic plasma membranes with normally silent scramblases activated under specific circumstances. Authors are wondering whether genes involved in deformation are similar in insects and mammals?

Kobayashi [13] evaluated the methods used to study membrane asymmetry, summarizing the factors that influence or limit lipid mapping assays and shine a spotlight on the most advanced developments that are applied to map and study transbilayer asymmetry of sphingomyelin. Current application of SDS-FRL immunoelectron microscopy-based and advanced fluorescent microscopy techniques provide a new view on dynamic sphingomyelin and other lipids transbilayer distribution in plasma membrane of single membraned and multi-membraned organelles and cells, respectively.

Fraser and coauthors [14] described how different parasites evolved unique strategies to take advantage of the loss of host cell membrane phosphatidylserine asymmetry. One of these processes, described by authors as apoptotic mimicry highlights the ability of these organisms to ‘hijack’ asymmetric properties of host membrane and utilize them in their intracellular parasitic lifecycles. If parasites can hijack the host’ ‘transmembrane lipid code’ can host cells subsequently ‘erase’ it? If so by what mechanism?

Villagrana and López-Marqués [15] summarized and critically reviewed all available data on the asymmetric distribution of phospholipids and glycolipids in plant plasma, inner and outer membranes of chloroplast envelope, thylakoidal and tonoplast membranes. They discussed intracellular trafficking dynamics as such as physiological role of plant P4-ATPase family members in intracellular lipid transport and their emerging but not ‘bona fide’ yet role in the generation and maintenance of lipid transbilayer asymmetry

Sharma and coauthors [16] have examined the use of advanced cryo-EM technique and reported that lateral lipid arrangement is retained during cryo-preservation and few angstrom lipid composition-dependent differences in thickness of bilayer can be confidently measured. Moreover, cryo-EM allowed to visualize and define the width and contrast differences between ordered and disordered nanodomains in synthetic and native membranes and build a tertiary bilayer structure from real-space cryo-EM images. These technical advances have a great potential for monitoring significant bilayer deformations, accompanying membrane protein conformational changes and large-scale individual functional transmembrane domain movements [17,18].

Deformability of membranes is a fundamental property of biological membranes and has essential roles in cellular function. Bending of bilayer can be induced by changes compositions of lipid and proteins integral to membrane, as well as membrane adjacent proteins (cytoskeleton). To facilitate the bending of membrane lipid molecules re-partition between two monolayers according to their different effective geometrical shapes. The review of Ruhoff and coauthors [19] focuses on the role of local spontaneous curvature thermodynamic instability and bending rigidity induced by interacting protein in the formation of membrane shapes at the mesoscopic scale. This impact arise from collective physical properties of lipids organized in lipid bilayer. Authors demonstrate how membrane shape remodeling guided by curvature-based lipid sorting/partitioning was explored in different theoretical and biomimetic membrane systems which allowed the researches to generate and detect membrane shapes.

Biological membranes are not absolutely flat. The asymmetric distribution of different amounts of lipids with different geometrical shapes between monolayers determine the overall curvature of a bilayer membrane. However, near zero curvature and essentially flat lipid bilayer can be frustrated and stressed if effective tension is unequal in the two leaflets due to different lipid packing order in each leaflet. Foley and coauthors [20] revealed the consequences of this ‘hidden but physically consequential’ stress potentially determining how much energy is needed to deform membrane, reshuffle lipid species and drive phase transitions. Authors rationalized the consequences of lateral and transbilayer lipid imbalance (most likely affected by proteins too) caused by membrane lateral heterogeneity (different lateral pressure profiles) and sorting/partitioning trends of lipid molecule able to flip spontaneously (sterol) to convincingly demonstrate that compositional and physical (packing order) lipid asymmetry are ubiquitously connected.

Wilke and Alvares [21] revisited the phenomenon of flexoelectricity as two-way mechanoelectrical effect that enables biological membranes to act like soft material and convert electric stimuli into mechanical event and vice versa. They describe membrane electrostatics in terms of polarization events which dielectric bilayer can develop in response to different asymmetric strains (electrochemical gradient (transmembrane pH imbalance)) or interactions (attraction and repelling of counterions, peripheral proteins etc) affecting bilayer bending rigidity, membrane fusion and fission.

The exploration of ‘lipid topogenesis’ was limited until recently to low and high eucaryotes and was originally used a categorical term for intracellular processes occurring simultaneously with or shortly after the synthesis of lipids [22,23]. Many new findings discussed by Abellon-Ruiz [24] have important implications for ‘lipid topogenesis’in double-membraned (diderm) bacteria. Through great advances in cryo-electron microscopy resolved multicomponent ATP-binding cassette transport system Mla system which constitutes a bacterial intermembrane trafficking system and maintains a lipid asymmetry in the outer membrane (OM) via retrograde transport of phospholipids back to the inner membrane (IM) therefore preventing phospholipid accumulation in the outer leaflet of the OM in normally grown cells. He discussed the mechanisms utilized by Gram-negative bacteria to shuttle lipids between IM and OM within their envelope. How intermembrane lipid gradients within two-membraned envelope are maintained and how different protein machineries work to support continuous lipid counterflows between IM and OM are still matter of debate.

Bogdanov [25] discussed the origin and maintenance of lipid asymmetry in biogenic cytoplasmic membrane of diderm Gram-negative bacteria driven potentially by ‘lipid-only’ flippase-less mechanism.

A new explanatory hypothesis and experimental models should be explored to understand how membrane lipid–protein lateral and transmembrane heterogeneity becomes controlled by the equilibrium and non-equilibrium states of the lipid–protein matrix. Novel approaches including high resolution time-lapse imaging along with design and development of different vectorial probes (vectorial lipidomics) should revolutionize our understanding of the physiological significance of lipid (a)symmetry as one of main architectural principles of membrane assembly and function.

Acknowledgements

I express a great gratitude to all contributing Authors for their enthusiasm and excellent and timely contributions. I would like also sincerely thank all ad hoc Reviewers for their time spent on thoughtful reviewing of submitted manuscripts and making constructive comments which help Authors to improve and strengthen their manuscripts. My special and sincere thanks go to excellent and very friendly Editorial Team of Emerging Topics in Life Sciences and particularly to Olivia Rowe and Zara Manwaring. I am very grateful for their instant and continuous support during the Editorial process.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant R01GM121493-6, European Union Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant H2020-MSCA-RISE-2015-690853 and NATO Science for Peace and Security Programme-SPS 98529.

Abbreviations

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FRL

freeze-fracture replica labeling

- IM

inner membrane

- OM

outer membrane

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Chiantia S and London E (2013) Lipid Bilayer Asymmetry. In Encyclopedia of Biophysics (Roberts GCK, eds), pp. 1250–1253, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg: 10.1007/978-3-642-16712-6_552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorent JH, Levental KR, Ganesan L, Rivera-Longsworth G, Sezgin E, Doktorova M et al. (2020) Plasma membranes are asymmetric in lipid unsaturation, packing and protein shape. Nat. Chem. Biol 16, 644–652 10.1038/s41589-020-0529-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogdanov M, Pyrshev K, Yesylevskyy S, Ryabichko S, Boiko V, Ivanchenko P et al. (2020) Phospholipid distribution in the cytoplasmic membrane of gram-negative bacteria is highly asymmetric, dynamic, and cell shape-dependent. Sci. Adv 6, eaaz6333 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doktorova M, Symons JL and Levental I (2020) Structural and functional consequences of reversible lipid asymmetry in living membranes. Nat. Chem. Biol 16, 1321–1330 10.1038/s41589-020-00688-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogdanov M, Dowhan W and Vitrac H (2014) Lipids and topological rules governing membrane protein assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 1475–1488 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogdanov M, Vitrac H and Dowhan W (2018) Flip-Flopping Membrane Proteins: How the Charge Balance Rule Governs Dynamic Membrane Protein Topology. In Biogenesis of Fatty Acids, Lipids and Membranes. Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology (Geiger O, ed.), pp. 1–28, Springer, Cham [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perozo E, Kloda A, Cortes DM and Martinac B (2002) Physical principles underlying the transduction of bilayer deformation forces during mechanosensitive channel gating. Nat. Struct. Biol 9, 696–703 10.1038/nsb827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petroff JT II, Dietzen NM, Santiago-McRae E, Deng B, Washington MS, Chen LJ et al. (2022) Open-channel structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel reveals a mechanism of leaflet-specific phospholipid modulation. Nat. Commun 13, 7017 10.1038/s41467-022-34813-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolson GL (2014) The fluid-mosaic model of membrane structure: still relevant to understanding the structure, function and dynamics of biological membranes after more than 40 years. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838, 1451–1466 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drin G. (2022) Creating and sensing asymmetric lipid distributions throughout the cell. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 7–19 10.1042/ETLS20220028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elani Y, Purushothaman S, Booth PJ, Seddon JM, Brooks NJ, Law RV et al. (2015) Measurements of the effect of membrane asymmetry on the mechanical properties of lipid bilayers. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 51, 6976–6979 10.1039/c5cc00712g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagao K and Umeda M (2022) Cellular function of (a)symmetric biological membranes. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 47–54 10.1093/pcp/pcad009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi T. (2023) Mapping trasmembrane distribution of sphingomyelin. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 31–45 10.1042/ETLS20220086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser M, Matuschewski K and Maier AG (2023) The enemy within: lipid asymmetry in intracellular parasite-host interactions. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 67–79 10.1042/ETLS20220089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villagrana R and López-Marqués R L (2022) Plant transbilayer lipid asymmetry and the role of lipid flippases. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 21–29 10.1042/ETLS20220083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma KD, Heberle FA and Waxham MN (2023) Visualizing lipid membrane structure with cryo-EM: past, present, and future. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 55–65 10.1042/ETLS20220090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arkhipova V, Guskov A and Slotboom DJ (2020) Structural ensemble of a glutamate transporter homologue in lipid nanodisc environment. Nat. Commun 11, 998 10.1038/s41467-020-14834-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X and Boudker O (2020) Large domain movements through the lipid bilayer mediate substrate release and inhibition of glutamate transporters. Elife 9, e58417 10.7554/eLife.58417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruhoff V, Bendix PM and Pezeshkian W (2023) Close, but not too close: a mesoscopic description of (a)symmetry and membrane shaping mechanisms. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 81–93 10.1042/ETLS20220078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foley SL, Varma M, Hossein A and Deserno M (2023) Elastic and thermodynamic consequences of lipid membrane asymmetry. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 95–110 10.1042/ETLS20220084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilke N and Alvares DS (2023) Out-of-plane deformability and its coupling with electrostatics in biomembranes. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 111–124 10.1042/EETLS20230001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell RM, Ballas LM and Coleman RA (1981) Lipid topogenesis. J. Lipid Res 22, 391–403 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)34952-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chauhan N, Farine L, Pandey K, Menon AK and Butikofer P (2016) Lipid topogenesis–35years on. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1861, 757–766 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abellon-Ruiz J. (2022) Forward or backward, that is the question: phospholipid trafficking by the Mla system. Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 125–135 10.1042/ETLS20220087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bogdanov M. (2023) Renovating double fence with or without notifying next door and across street neighbors: why biogenic cytoplasmic membrane of Gram-negative bacteria display asymmetry? Emerg. Top. Life Sci 7, 137–150 10.1042/ETLS20220030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]