Abstract

The chaperone-encoding groESL and dnaK operons constitute the CIRCE regulon of Bacillus subtilis. Both operons are under negative control of the repressor protein HrcA, which interacts with the CIRCE operator and whose activity is modulated by the GroESL chaperone machine. In this report, we demonstrate that induction of the CIRCE regulon can also be accomplished by ethanol stress and puromycin. Introduction of the hrcA gene and a transcriptional fusion under the control of the CIRCE operator into Escherichia coli allowed induction of this fusion by heat shock, ethanol stress, and overproduction of GroESL substrates. The expression level of this hrcA-bgaB fusion inversely correlated with the amount of GroE machinery present in the cells. Therefore, all inducing conditions seem to lead to induction via titration of the GroE chaperonins by the increased level of nonnative proteins formed. Puromycin treatment failed to induce the ςB-dependent general stress regulon, indicating that nonnative proteins in general do not trigger this response. Reconstitution of HrcA-dependent heat shock regulation of B. subtilis in E. coli and complementation of E. coli groESL mutants by B. subtilis groESL indicate that the GroE chaperonin systems of the two bacterial species are functionally exchangeable.

Molecular chaperones such as those represented by the DnaK and GroE machines are induced by heat shock in all organisms from bacteria to humans. Regulation of this heat shock response has been extensively analyzed in Escherichia coli, where induction of one class of heat shock proteins including the molecular chaperones is triggered by the accumulation of nonnative proteins in the cytoplasm and governed by the alternative sigma factor ς32 (4, 22, 33–35). Increasing the level of active ς32 due to stabilization of the protein and enhanced translation of its mRNA following thermal upshock is responsible for the induction of this heat shock regulon (8, 35, 37). The activity of ς32 is modulated by the DnaK chaperone system which sequesters most of the ς32 molecules under physiological conditions and most probably presents them to a protease such as FtsH (7, 16, 38). Upon accumulation of nonnative proteins within the cytoplasm, the DnaK system is titrated by these substrates, and thereby the amount of active ς32 increases transiently. Since chaperones perform important functions in preventing aggregation of nonnative proteins, they are induced by not only heat shock but also by other stimuli such as ethanol, puromycin, viral infection, nalidixic acid, heavy metals such as cadmium chloride, glucose starvation, and osmotic or oxidative stress (13, 19, 22). Induction of these conserved heat shock proteins by a variety of different stimuli is common in bacteria and higher organisms (23).

In Bacillus subtilis, at least four classes of heat shock genes can be distinguished. Class I, which comprises the groESL and dnaK operons, also designated the CIRCE regulon, is transcribed from vegetative promoters and subject to negative control by the HrcA repressor, which acts at the transcriptional level by interacting with an operator, the CIRCE element, located immediately downstream of the start point of transcription (30, 42, 43). Since purified HrcA repressor aggregates in vitro, it was postulated that GroE proteins are required to maintain HrcA in an active state (21). Members of class II absolutely require the alternative sigma factor ςB for their induction by heat and other stresses (10). Class III currently comprises clpC, clpP, and clpE, and heat and stress induction is mediated by the repressor CtsR (class III stress gene repressor [5]). Heat shock genes, such as trxA, lon, ftsH, htpG, and ahpCF, not belonging to classes I through III are currently grouped in class IV, but the mechanisms which are responsible for heat induction of these genes have not been characterized (2, 10, 26, 31). In contrast to the other classes and the induction profile in other bacteria, class I heat shock genes seem to be subject to a heat-specific induction in B. subtilis (10, 11, 39).

We now show that this class of genes is induced not only by heat shock but also by a group of related stimuli including ethanol stress, treatment with puromycin, and production of inclusion bodies which probably all share the increased formation of nonnative proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used during this study are listed in Table 1. The B. subtilis and E. coli strains were cultivated under vigorous agitation in LB (25) at 37 and 30°C, respectively. Stresses were imposed during exponential growth according to the following scheme: heat shock (transfer of the culture to 50°C [B. subtilis] or 42°C [E. coli]); salt stress (addition of NaCl to a final concentration of 4% [wt/vol]); ethanol (addition of ethanol to a final concentration of 4 or 5% [vol/vol]); and puromycin (addition of the inhibitor to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml). Cultures were exposed to the different stimuli for the times indicated in the corresponding figures and figure legends.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| A190 | ΔgroEL Kmr Δ(lac-pro) hsdD5 (rK− mK−) thi F′[traD36 proAB lacIqlacZΔM15] | 12 |

| DH5α | F−φ80d lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK−mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA69 | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| DH10B | Strr F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80d lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK endA1 nupG | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| Ω425 | groEL100 groES+::Tn10 | 21 |

| Ω427 | groEL+groES30::Tn10 | 21 |

| Bacillus subtilis | ||

| PY22 | trpC2 | P. Youngman |

| 1012 | trpC2 leuA8 metB5 hsrM1 | 24 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript II SK/KS+/− | Cloning vector, Apr | Stratagene |

| pSPT18 | Cloning vector, Apr | Boehringer Mannheim |

| pAM101 | hrcA hrcA::bgaB, Apr Kmr | 21 |

| pAM103 | pAM101 with tet instead of neo, Apr Tcr | This work |

| pBAD-EL | pBAD30 containing the E. coli groEL, Apr | 12 |

| pBAD33 | Expression vector allowing cloning of target genes downstream of the PBAD promoter, Cmr | 9 |

| pBAD33-groESL | pBAD33 containing a 2.0-kb PCR fragment encoding E. coli groES and groEL, Cmr | This work |

| pDS12-Placwt-9A-lucI | pDS12 containing the firefly lucI, Apr | B. Bukau |

| pKSMsigB | pBluescript II KS with a 2.9-kb PCR fragment encoding B. subtilis rsbV, rsbW, sigB, and rsbX inserted into the EcoRV site | This work |

| pKSMsigBC | pBluescript II KS containing B. subtilis rsbV, rsbW, and sigB | This work |

| pKSB52 | pBluescript II KS containing a 610-bp HindIII-ClaI fragment of B. subtilis sigB | This work |

| pQE40-tst | pQE40 containing rat tst | T. Langer |

| pREP9 | E. coli-B. subtilis shuttle vector allowing cloning of target genes downstream of an IPTG-inducible promoter, Cmr Kmr | 15 |

| pREP9-tst | pREP9 containing a 900-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment encoding rat tst, Cmr Kmr | This work |

| pREP9-lucI | pREP9 containing a 1,700-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment encoding firefly lucI, Cmr Kmr | This work |

| pREP9-cbbM | pREP9 containing a 1,500-bp SalI-HindIII fragment encoding R. capsulatus cbbM, Cmr Kmr | This work |

| pSEG247 | pSPT18 containing a 800-bp HindIII-EcoRI fragment of B. subtilis groEL | This work |

RNA isolation and analysis of transcription.

Total RNA was prepared by a modification (39) of the acid-phenol method of Majumdar et al. (17). For slot blot analysis, serial dilutions of the RNA were transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane by slot blotting and hybridized with digoxygenin-labeled RNA probes synthesized in vitro from linearized plasmids as instructed by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). The fluorescence of the Vistra ECF substrate was quantified with the Storm860 system from Molecular Dynamics, using RNA dilutions with a signal strength in the linear range of the instrument. Induction ratios were calculated by setting the value of the corresponding control (nontreated or exponentially growing culture) to 1. For the preparation of the digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes, a DNA fragment encompassing the four downstream genes of the sigB operon was amplified from chromosomal DNA of the wild-type strain 168 by using the synthetic oligonucleotides sigBF (5′-CGCAGGAAATGGTCAAAAAC) and sigBR (5′-AATAAATCAGCCAATCTCCCTC). The PCR fragment was cloned into pBluescript II KS− digested with EcoRV. The resulting plasmid, pKSMsigB was digested with ClaI and religated, yielding plasmid pKSMsigBC. After digestion of pKSMsigBC with HindIII and BamHI, filling in the ends with Klenow polymerase, and religation of the larger fragment, pKSMB52 was obtained. Synthesis of RNA in vitro with T3 RNA polymerase after linearization of pKSMB52 with SacI can be used for the production of a digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe specific for sigB. A suitable fragment for the preparation of a groEL-specific probe was generated by cloning an 800-bp HindIII-EcoRI fragment from pASG145 (27) encoding groEL of B. subtilis into pSPT18. The resulting plasmid, pSEG247, can be used for the preparation of digoxigenin-labeled, groEL-specific RNA probe with T7 RNA polymerase after linearization with HindIII.

Construction of plasmids.

To allow regulated expression of GroEL substrates, plasmids pREP9-tst, pREP9-lucI, and pREP9-cbbM were constructed. For the construction of pREP9-tst, a DNA fragment encoding the rat tst gene was isolated by BamHI-HindIII digestion of pQE40-tst and cloned into pREP9 digested with BamHI and HindIII. To obtain pREP9-lucI, the lucI gene was amplified from pDS12-Placwt-9A-lucI by using the synthetic oligonucleotides LUCI-1 (5′-GGCCATGGATCCATGGAAGACGCCAAAAACATAAAGA) and LUCI-2 (5′-GGCCATAAGCTTTTACAATTTGGGCTTTCCGCCCTT). The PCR fragment was cloned into pREP9 digested with BamHI and HindIII. To construct pREP9-cbbM, the cbbM gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of Rhodobacter capsulatus by using the synthetic oligonucleotides RubisCo-3 (5′-GGCCATGTCGACATGGATCAGTCTAACCGTTACGCCC) and RubisCo-2 (5′-GGCCATAAGCTTTCAGTTCACGCCCAGAGCAACGCG). The PCR product was cloned into pREP9 digested with SalI and HindIII. To allow overproduction of the GroE chaperone machine from E. coli or B. subtilis, pBAD33-groESL and pREP9-groESL were constructed. For the construction of pBAD33-groESL, the groES and groEL genes of E. coli were amplified from chromosomal DNA by using the synthetic oligonucleotides ECES (5′-GGCCATGAGCTCAAAGGAGAGTTATCAATGAATATTCGT) and ECEL (5′-GGCCATAAGCTTTTACATCATGCCGCCCATGCCACC). The PCR fragment was cloned into pBAD33 digested with SacI and HindIII. To obtain pREP9-groESL, the groES and groEL genes of B. subtilis were amplified from chromosomal DNA by using the synthetic oligonucleotides PP1 (5′-GGCCATGGATCCATGTTAAAGCCATTAGGTGATCGC) and EL-B2 5′-GGCCATGGATCCTTACATCATTCCACCCATACCGCC). The PCR fragment was cloned into pREP9 digested with BamHI. To replace the kanamycin resistance gene of pAM101 with a tetracycline resistance gene, tet was isolated from pBgaB-tet by XbaI-NotI digestion and cloned into pAM101 digested with XbaI and NotI, yielding plasmid pAM103.

Fractionation of E. coli proteins.

Bacterial cultures (10-ml aliquots) were rapidly cooled to 0°C in an ice water bath and harvested by centrifugation (10 min, 4°C, 5,000 × g). Pellets were resuspended in 10× lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 100 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 15% [wt/vol] sucrose, 1 mg of lysozyme per ml) according to optical density (50 μl of lysis buffer for a 10-ml culture with an optical density at 600 nm of 1) and frozen at −20°C. After thawing at 0°C, addition of 10 volumes of ice-cold water, and mixing, the viscous, turbid solution was sonicated with a Branson Cell Disruptor B15 (microtip, level 6, 50% duty cycle, eight strokes) while cooling. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation at 25,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatants were removed and subjected to precipitation with trichloracetic acid (TCA; 10%, final concentration), and pellets were resuspended in sample buffer. Equal aliquots of soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by immunoblotting or staining with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis.

Protein extracts were prepared by passage through a French press after cells had been harvested on ice. Equal amounts of protein (400 μg) were loaded. Proteins were separated with IPG strips (pH 4 to 8) in the first dimension on the Multiphor apparatus supplied by Pharmacia, equilibrated, loaded onto 12.5% polyacrylamide gels, and separated according to molecular mass with the Investigator electrophoresis system of ESA Inc. Proteins were visualized by staining with Phastgel Blue R (Pharmacia Biotech).

General methods.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were performed as described previously (40). B. subtilis transformation was carried out as described by Yasbin et al. (41), and transformants were selected on agar containing kanamycin (20 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml). All DNA manipulations and E. coli transformations were carried out according to standard protocols (25). β-Galactosidase activities were determined as described elsewhere (20).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ethanol and puromycin trigger induction of the CIRCE regulon in B. subtilis.

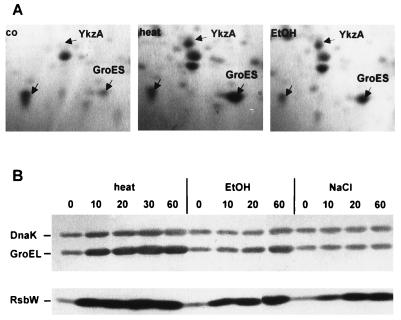

In an effort to identify additional stress proteins of B. subtilis, exponentially growing wild-type bacteria were challenged with different stress factors, and their protein patterns were analyzed by two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis (1). These analyses revealed that the amount of GroES increased not only after heat shock but also after exposure to ethanol stress (Fig. 1A) but not after salt stress or glucose limitation (data not shown). A similar induction pattern was also observed for GroEL and DnaK (data not shown). To quantitate these observations, the kinetics of expression of DnaK and GroEL after heat shock, ethanol, and salt stress were measured by Western blot analysis. Crude extracts were prepared from exponentially growing B. subtilis PY22, harvested immediately before (time zero) and at different times after stress treatment; the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and finally probed with antibodies prepared against GroEL, DnaK, and RsbW. Whereas heat shock triggered a rapid increase in the level of GroEL and DnaK as previously reported, ethanol treatment resulted in a slow but continuous accumulation of both proteins (Fig. 1B); salt shock did not influence the level of the chaperones. In contrast, all three stimuli resulted in a rapid increase of the level of RsbW, a class II ςB-dependent heat shock protein.

FIG. 1.

Influence of heat shock, ethanol, and salt stress on levels of GroEL, DnaK, and RsbW. B. subtilis PY22 was grown in LB, and stresses were imposed during exponential growth by transferring the culture from 37 to 48°C or by adding ethanol (EtOH) or NaCl to a final concentration of 4% (vol/vol or wt/vol, respectively). (A) Sections of Coomassie blue R-350-stained two-dimensional protein gels prepared from crude extracts of growing cells (co) or cells harvested 90 min after imposition of stress. Besides GroES, the ςB-dependent stress protein YkzA and a vegetative protein are labeled. (B) Equal amounts of crude protein extracts (50 μg per lane) prepared from bacteria harvested at the time points (minutes) indicated were separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, levels of GroEL, DnaK, and RsbW were determined with specific antibodies raised against the corresponding proteins as described previously (3, 29, 32).

To determine whether accumulation of the chaperones was due to an increase in their amount of transcript, the level of groESL mRNA was determined by slot blot analysis. Heat shock triggered a rapid increase in the level of groESL mRNA as expected, but ethanol caused a slower but continuous increase in the amount of groESL mRNA (Fig. 2). To confirm these results by a different approach, B. subtilis 1012 carrying an hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion (20) was subjected to stress treatment. When a strain carrying this fusion was shifted from 37 to 50°C, β-galactosidase activity increased eightfold within 15 min, whereas treatment with 5% (vol/vol) ethanol caused a slow gradual increase, resulting in a fivefold induction after 60 min (Table 2). Addition of 4% (wt/vol) NaCl did not result in any increase in the expression of the hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion. Significant increases in the groESL mRNA level were also observed after treatment with puromycin (20 μg/ml, final concentration) (Fig. 2). For sigB, which is itself a member of class II heat shock genes, the slot blot analysis revealed strong induction as quickly as 3 min after heat shock, ethanol, or salt stress (Fig. 2) but no induction after addition of puromycin (Fig. 2). Although class I and class II heat shock genes share some inducers such as heat shock and ethanol, the intracellular signals which trigger induction seem to differ since both classes display different induction kinetics and different induction profiles. For example, ethanol treatment results in a fast induction of class II but slow accumulation of class I heat shock proteins, and class II is not induced by puromycin, whereas class I does not respond to salt stress or starvation for glucose.

FIG. 2.

Levels of groEL and sigB mRNA in B. subtilis after challenge with heat, ethanol, or salt stress and puromycin. Serial dilutions of total RNA prepared from B. subtilis PY22 before (co) and at 5, 10, 15, 20, 40, and 60 min after exposure to stress were bound to a positively charged nylon membrane and hybridized with the digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes specific for groEL and sigB (18, 39). The hybridization signals were quantified with a fluorimager. The mRNA level in the control prior to stress was set to 1, and the induction ratios are shown. Stresses were triggered as described in Materials and Methods. ▪, 50°C; □, 4% ethanol; ▧, 4% NaCl; ░⃞, 20 μg of puromycin per ml.

TABLE 2.

Induction of an hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion in B. subtilis 1012 and in E. coli DH10Ba

| Species | Stress factor | Relative

β-galactosidase activity at indicated time (min) after stress

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 30 | 60 | ||

| B. subtilis | Heat (37→50°C) | 8.6 | 10.1 | 7.6 |

| Ethanol (5%) | 1.2 | 2.3 | 4.8 | |

| NaCl (4%) | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| E. coli | Heat (30→42°C) | 4.3 | 5.1 | 4.2 |

| Ethanol (5%) | 3.0 | 4.9 | 6.7 | |

| NaCl (4%) | 1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C (B. subtilis) or 30°C (E. coli) to mid-exponential phase and then challenged with the stress factors indicated. Samples were withdrawn immediately before (time zero) and 15, 30, and 60 min after exposure to the stress factor, and β-galactosidase activities relative to those at time zero (assigned a value of 1) were determined as described elsewhere (20). The results are the averages of three experiments; standard deviations were less than 10%.

Induction of an hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion in E. coli by heat, ethanol, and overproduction of GroESL substrates.

Recently, the GroE chaperonin machine has been shown to be a major modulator of the regulation of the genes of the CIRCE regulon (21). The heat shock regulation of hrcA-bgaB and groE-bgaB transcriptional fusions both carrying the CIRCE element could be reconstituted in E. coli by supplying the HrcA repressor under control of a constitutive promoter (21, 42). Heat shock, ethanol stress, and treatment with puromycin most probably produce nonnative proteins and thereby titrate the GroE chaperonin system. This in turn may lead to an accumulation of inactive HrcA repressor and induction of the CIRCE regulon (21). We asked whether this mechanism might also trigger induction of an hrcA-bgaB fusion in E. coli. To test this hypothesis, E. coli DH10B harboring plasmid pAM101 (21), which synthesizes HrcA from a constitutive promoter and carries a transcriptional fusion between the CIRCE-controlled hrcA promoter and bgaB, was challenged with different stress regimens. In agreement with previous data, β-galactosidase activity increased rapidly within 15 min when this strain was grown in LB at 30°C and shifted to 42°C (Table 2 and reference 21). Treatment of DH10B with 5% (vol/vol) ethanol was as effective as the heat shock in induction, whereas 4% NaCl failed to induce expression of hrcA-bgaB (Table 2).

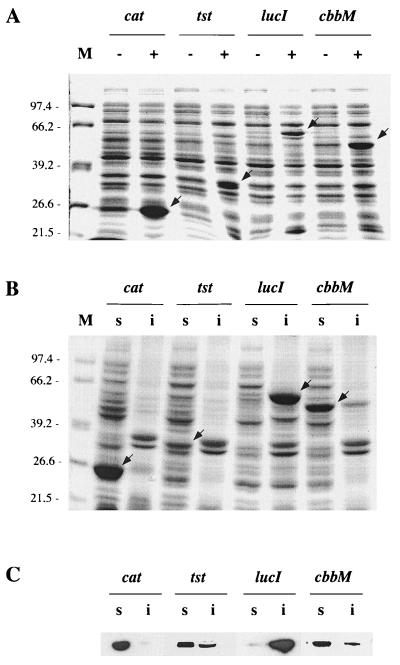

If indeed nonnative proteins are the signal for induction of class I genes in E. coli as assumed for B. subtilis, then overproduction of GroE substrates should induce the hrcA-bgaB fusion indirectly by titrating GroEL. E. coli DH10B was transformed with plasmid pREP9 (15) or recombinant derivatives carrying either tst, lucI, or cbbM under the control of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter. Growth in the presence of IPTG caused overproduction of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, rhodanese, luciferase, and RubisCO (Fig. 3A). Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase accumulated to levels at least as high as those for the other three proteins (Fig. 3A) and remained almost completely in the soluble fraction (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, overexpression of rhodanese, luciferase, and RubisCO resulted in the accumulation of considerable amounts of the proteins in the insoluble fraction, with luciferase occurring almost exclusively in this fraction (Fig. 3B and C). This formation of inclusion bodies was accompanied by a low but reproducible induction of the hrcA-bgaB fusion in E. coli (Table 3). Since overproduction of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, which is not a substrate of the GroE system (6, 14), did not induce the hrcA-bgaB fusion (Table 3), overproduction of a protein per se cannot be the signal for the induction of CIRCE-regulated genes. Rather, overproduction of substrates of the GroESL chaperonin system, such as rhodanese which requires multiple GroE-driven reaction cycles for proper folding (6), might lead to a titration of GroEL and cause the increased expression of the hrcA-bgaB fusion.

FIG. 3.

Overproduction and localization of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase and GroEL substrates in E. coli. E. coli DH10B transformed with pREP9, pREP9-tst, pREP9-lucI, or pREP9-cbbM, permitting overproduction of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat), rhodanese (tst), luciferase (lucI), or RubisCO (cbbM), respectively, were grown to mid-exponential phase and induced with 1 mM IPTG. (A) Whole-cell fractions corresponding to identical amounts of cell culture were collected before (−) or 2 h after (+) the addition of IPTG and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of marker proteins (M) are given; arrowheads indicate localization of the overproduced proteins. (B) Soluble (s) and insoluble (i) fractions of an extract prepared from a culture induced for 2 h with IPTG were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots corresponding to identical amounts of cell culture were loaded onto all lanes. (C) Samples identical to those in panel B were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The membranes were probed with anti-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, antirhodanese, antiluciferase, or anti-RubisCO antibodies and developed by a colorimetric assay.

TABLE 3.

Induction of an hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion by overproduction of GroE substrates in E. coli DH10Ba

| Plasmid | Relative β-galactosidase activity at

indicated time (h) after addition of IPTG

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| pREP9 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pREP9-tst | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| pREP9-lucI | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| pREP9-cbbM | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

E. coli DH10B carrying pAM101 (21) and one of the indicated plasmids was grown in LB to mid-exponential phase and then treated with 1 mM IPTG to induce production of the proteins whose genes had been cloned into pREP9. Samples were withdrawn from the cultures at the times indicated. β-Galactosidase activities relative to those at time zero (assigned a value of 1) were determined as described elsewhere (20). All experiments were performed in triplicate; standard deviations were less than 10%.

Variations of the level of GroEL in E. coli influence the expression of an hrcA-bgaB fusion.

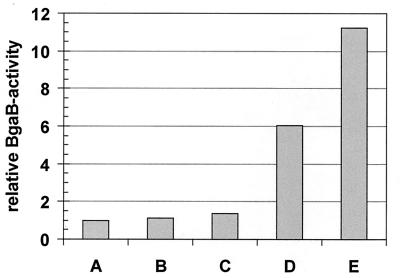

Because overproduction of heterologous proteins acts most likely indirectly by sequestering the GroE chaperonin, varying the level of GroESL in E. coli should affect expression of class I genes in a way similar to that described for B. subtilis (21). To test this assumption, we examined whether depletion of the GroE proteins in E. coli would result in induction of an hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion. To this end, E. coli A190 in which the chromosomal groEL gene has been replaced by a kanamycin resistance cassette and which carries the groEL gene on a plasmid under the control of the PBAD promoter (12) was transformed with pAM103, a tetracycline-resistant derivative of pAM101 carrying an hrcA-bgaB operon fusion (21). This strain was then grown in the presence of different arabinose concentrations, and β-galactosidase activities were measured. The lowest enzymatic activity was measured in the presence of 0.2% arabinose (Fig. 4). Decreasing the sugar concentration reduced the level of GroEL as determined by immunoblotting (data not shown) and simultaneously increased expression of the hrcA-bgaB fusion. Addition of the anti-inducer glucose increased the level of β-galactosidase even further (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Depletion of GroEL induces an hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion in E. coli. E. coli A190 carrying the two plasmids pAM103 and pBAD33-groESL (expressing the E. coli groESL genes) was grown in the presence of 0.2% arabinose in LB overnight. The cells were then washed to remove the inducer arabinose and resuspended in LB medium either in the absence or in the presence of the indicated arabinose concentrations or in the presence of 0.5% glucose as anti-inducer. Expression of the hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion expressed from pAM103 was assayed 4 h after the resuspension. A, 0.2% arabinose; B, 0.06% arabinose; C, 0.02% arabinose; D, no arabinose; E, 0.5% glucose.

In contrast to the latter results, preloading the cells with E. coli GroESL proteins should reduce a later heat shock induction of the hrcA-bgaB fusion if the E. coli GroE chaperone machine can fully substitute for GroESL of B. subtilis in this regulation. Addition of 0.2% arabinose to the growth medium of E. coli DH10B carrying pAM101 and pBAD33-groESL resulted in overproduction of GroESL proteins during exponential growth (as visualized by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining [data not shown]) and indeed significantly reduced the heat inducibility of the hrcA-bgaB fusion (Table 4). Arabinose had no effect on the heat induction in cells containing only the empty vector pBAD33. To support the notion that the GroESL chaperonins of E. coli and B. subtilis are functionally exchangeable, the B. subtilis groESL operon was inserted into the vector pREP9. This recombinant plasmid, pREP9-groESL, complemented E. coli groES30 and groEL100 temperature-sensitive mutants for growth at the nonpermissive temperature (data not shown) as previously described for the groE operon of Bacillus stearothermophilus (28).

TABLE 4.

Overproduction of E. coli GroESL causes reduced heat induction of an hrcA-bgaB transcriptional fusion in E. coli DH10Ba

| Plasmid | Relative β-galactosidase activity at

indicated time (min) after heat shock

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 30 | 60 | 120 | |

| pBAD33b | 2.8 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.4 |

| pBAD33-groESL | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

Overproduction of GroES and GroEL after addition of arabinose was verified by SDS-PAGE. To analyze the effect of overproduction of the GroE proteins on the expression of an hrcA-bgaB operon fusion, pBAD33 or pBAD33-groESL was transformed into E. coli DH10B carrying pAM101. Both strains were first grown in LB medium at 30°C in the absence of arabinose to mid-exponential phase, then arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2%, and 1 h later the culture was shifted from 30 to 42°C. Samples were taken immediately before thermal upshift (time zero) and different times after the heat shock. β-Galactosidase activities relative to those at time zero (assigned a value of 1) were determined as described elsewhere (20). Induction of the two strains was carried out three times with standard deviations less than 10%.

pBAD33 (9) permits expression of target genes from the PBAD promoter, which is under negative control of the AraC repressor.

In summary, our results clearly show that besides heat shock, other stimuli such as ethanol and puromycin can induce the heat shock genes of the CIRCE regulon of B. subtilis. In contrast to class II heat shock genes, which are induced by entirely different signals, induction of the CIRCE regulon remains confined to a group of related stimuli which all most likely produce enhanced amounts of nonnative proteins. The same signal seems to be responsible for the induction of these genes after their transfer into E. coli.

There are bacterial species inheriting both the ς32 and the HrcA-CIRCE mechanisms (21). In both cases, negative autoregulation is guaranteed. Regulation of chaperone expression by different mechanisms also allows specific induction of the groE operon when increased amounts of GroE proteins are specifically needed, e.g., in R. capsulatus and in Synechococcus spp. RubisCO is a substrate for GroEL, and synthesis of RubisCO is accompanied by an increase in the amount of GroE proteins (36).

We propose that titration of the GroE chaperonin by increased levels of nonnative proteins presumably prevents (re)activation of the HrcA repressor and therefore might permit increased expression of class I heat shock genes. This proposed mechanism of negative autoregulation might ensure a rapid activation and deactivation of the genes of the CIRCE regulon. In addition, this kind of regulation permits precise fine adjustments, to ensure the adequate production of molecular chaperones depending on the growth temperature and other physiological conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A. Mogk and A. Völker contributed equally to this work.

We thank A. Harang for excellent technical assistance, B. Bukau for pDS12-Placwt-9A-lucI and the antibodies against luciferase and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, M. Ehrmann for pBAD33, U. Hartl for the antibody against rhodanese, G. Klug for chromosomal DNA of R. capsulatus, T. Langer for plasmid pQE40-tst, P. Lund for E. coli A190, and F. R. Tabita for the antibody against RubisCO.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (He 1887/2-4 to M. Hecker, Schu 414/9-4 to W. Schumann, and Vö 629/2-2 to U. Völker) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie to M. Hecker, W. Schumann, and U. Völker.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antelmann H, Bernhardt J, Schmid R, Mach H, Völker U, Hecker M. First steps from a two-dimensional protein index towards a response-regulation map for Bacillus subtilis. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1451–1463. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Hecker M. General and oxidative stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: cloning, expression, and mutation of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6571–6578. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6571-6578.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson A K, Haldenwang W G. Bacillus subtilis ςBis regulated by a binding protein (RsbW) that blocks its association with core RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2330–2334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig E A, Gross C A. Is hsp70 the cellular thermometer? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derre I, Msadek T. Presented at the 9th International Conference on Bacilli, Lausanne, Switzerland. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewalt K L, Hendrick J P, Houry W A, Hartl F U. In vivoobservation of polypeptide flux through the bacterial chaperonin system. Cell. 1997;90:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamer J, Multhaup G, Tomoyasu T, McCarty J S, Rudiger S, Schonfeld H J, Schirra C, Bujard H, Bukau B. A cycle of binding and release of the DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE chaperones regulates activity of the Escherichia coli heat shock transcription factor ς32. EMBO J. 1996;15:607–617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossman A D, Straus D B, Walter W A, Gross C A. ς32 synthesis can regulate the synthesis of heat shock proteins in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1987;1:179–184. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman L M, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBADpromoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecker M, Schumann W, Völker U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.396932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecker M, Völker U. General stress proteins in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;74:197–213. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivic A, Olden D, Wallington E J, Lund P A. Deletion of Escherichia coli groEL is complemented by a Rhizobium leguminosarum groELhomologue at 37°C but not at 43°C. Gene. 1997;194:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins D E, Auger E A, Matin A. Role of RpoH, a heat shock regulator protein, in Escherichia colicarbon starvation protein synthesis and survival. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1992–1996. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1992-1996.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H B, Kang C. Activity of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase overproduced in E. coliwith wild type and mutant GroEL. Biochem Int. 1991;25:381–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeGrice S F. Regulated promoter for high-level expression of heterologous genes in Bacillus subtilis. In: Goeddel D V, editor. Gene expression technology. London, England: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberek K, Georgopoulos C. Autoregulation of the Escherichia coliheat shock response by the DnaK and DnaJ heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11019–11023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majumdar D, Avissar Y J, Wyche J H. Simultaneous and rapid isolation of bacterial and eukaryotic DNA and RNA—a new approach for isolating DNA. BioTechniques. 1991;11:94–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maul B, Völker U, Riethdorf S, Engelmann S, Hecker M. ςB-dependent regulation of gsiB in response to multiple stimuli in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:114–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02456620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meury J, Kohiyama M. Role of heat shock protein DnaK in osmotic adaptation of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4404–4410. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4404-4410.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mogk A, Hayward R, Schumann W. Integrative vectors for constructing single-copy transcriptional fusions between Bacillus subtilispromoters and various reporter genes encoding heat-stable enzymes. Gene. 1996;182:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mogk A, Homuth G, Scholz C, Kim L, Schmid F X, Schumann W. The groE chaperonin machine is a major modulator of the CIRCE heat shock regulon of Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 1997;16:4579–4590. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neidhardt F C, VanBogelen R A. Heat shock response. In: Neidhardt F, Ingraham J, Low K, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 1334–1345. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nover L. Inducers of Hsp synthesis: heat shock and chemical stressors. In: Nover L, editor. Heat shock response. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito H, Sibata T, Ando T. Mapping of genes determining nonpermissiveness and host-specific restriction to bacteriophages in Bacillus subtilisMarburg. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;170:117–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00337785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch J, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scharf C, Riethdorf S, Ernst H, Engelmann S, Völker U, Hecker M. Thioredoxin is an essential protein induced by multiple stresses in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1869–1877. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1869-1877.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt A, Schiesswohl M, Völker U, Hecker M, Schumann W. Cloning, sequencing, mapping, and transcriptional analysis of the groESL operon from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3993–3999. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3993-3999.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schon U, Schumann W. Overproduction, purification and characterization of GroES and GroEL from thermophilic Bacillus stearothermophilus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schön U, Schumann W. Construction of His6-tagging vectors allowing single-step purification of GroES and other polypeptides produced in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1994;147:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz A, Schumann W. hrcA, the first gene of the Bacillus subtilis dnaKoperon, encodes a negative regulator of class I heat shock genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1088–1093. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1088-1093.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz A, Schwab S, Homuth G, Versteeg S, Schumann W. The htpG gene of Bacillus subtilisbelongs to class III heat shock genes and is under negative control. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3103–3109. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3103-3109.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz A, Tzschaschel B, Schumann W. Isolation and analysis of mutants of the dnaK operon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skelly S, Coleman T, Fu C F, Brot N, Weissbach H. Correlation between the 32-kDa ς factor levels and in vitro expression of Escherichia coliheat shock genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8365–8369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Straus D, Walter W, Gross C A. DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE heat shock proteins negatively regulate heat shock gene expression by controlling the synthesis and stability of ς32. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2202–2209. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Straus D B, Walter W A, Gross C A. The heat shock response of Escherichia coli is regulated by changes in the concentration of ς32. Nature. 1987;329:348–351. doi: 10.1038/329348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terlesky K C, Tabita F R. Purification and characterization of the chaperonin 10 and chaperonin 60 proteins from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8181–8186. doi: 10.1021/bi00247a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tilly K, Spence J, Georgopoulos C. Modulation of stability of the Escherichia coli heat shock regulatory factor ς32. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1585–1589. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1585-1589.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomoyasu T, Gamer J, Bukau B, Kanemori M, Mori H, Rutman A J, Oppenheim A B, Yura T, Yamanaka K, Niki H, Hiraga S, Ogura T. Escherichia coli FtsH is a membrane-bound, ATP-dependent protease which degrades the heat-shock transcription factor ς32. EMBO J. 1995;14:2551–2560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Völker U, Engelmann S, Maul B, Riethdorf S, Völker A, Schmid R, Mach H, Hecker M. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1994;140:741–752. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-4-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Völker U, Völker A, Maul B, Hecker M, Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. Separate mechanisms activate ςB of Bacillus subtilisin response to environmental and metabolic stresses. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3771–3780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3771-3780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasbin R E, Wilson G A, Young T E. Transformation and transfection of lysogenic strains of Bacillus subtilis168. J Bacteriol. 1973;113:540–548. doi: 10.1128/jb.113.2.540-548.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan G, Wong S L. Isolation and characterization of Bacillus subtilis groE regulatory mutants: evidence for orf39 in the dnaK operon as a repressor gene in regulating the expression of both groE and dnaK. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6462–6468. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6462-6468.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuber U, Schumann W. CIRCE, a novel heat shock element involved in regulation of the heat shock operon dnaK of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1359–1363. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.5.1359-1363.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]