Abstract

Objective

To describe the baseline characteristics of patients with positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) who were enrolled in an international registry, the Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking (APS ACTION) clinical database and repository, overall and by clinical and laboratory subtypes.

Methods

The APS ACTION registry includes adults who persistently had positivity for aPLs. We evaluated baseline sociodemographic and aPL-related (APS classification criteria and “non-criteria”) characteristics of patients overall and in subgroups (aPL-positive without APS, APS overall, thrombotic APS only, obstetric APS only, and both thrombotic APS/obstetric APS). We assessed baseline characteristics of patients tested for the presence of three aPLs (lupus anticoagulant [LAC] test, anticardiolipin antibody [aCL], and anti–β2-glycoprotein I [anti-β2GPI]) antibodies by aPL profiles (LAC only, single, double, and triple aPL positivity).

Results

The 804 aPL-positive patients assessed in the present study had a mean age of 45 ± 13 years, were 74% female, and 68% White; additionally, 36% had other systemic autoimmune diseases. Of these 804 aPL-positive patients, 80% were classified as having APS (with 55% having thrombotic APS, 9% obstetric APS, and 15% thrombotic APS/obstetric APS). In the overall cohort, 71% had vascular thrombosis, 50% with a history of pregnancy had obstetric morbidity, and 56% had experienced at least one non-criteria manifestation. Among those with three aPLs tested (n = 660), 42% were triple aPL–positive. While single–, double–, and triple aPL–positive subgroups had similar frequencies of vascular, obstetric, and non-criteria events, these events were lowest in the single aPL subgroup, which consisted of aCLs or anti-β2GPI only.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the heterogeneity of aPL-related clinical manifestations and laboratory profiles in a multicenter international cohort. Within single aPL positivity, LAC may be a major contributor to clinical events. Future prospective analyses, using standardized core laboratory aPL tests, will help clarify aPL risk profiles and improve risk stratification.

INTRODUCTION

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized as an autoimmune disease marked by thromboses and/or pregnancy morbidity with persistent positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs), lupus anticoagulant (LAC) test, anticardiolipin antibodies (aCLs), and/or anti–β2-glycoprotein I (anti-β2GPI) antibodies, as defined by the revised Sapporo criteria for APS (1, 2). Other well-recognized “non-criteria” clinical manifestations may occur in aPL-positive patients, including thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, livedo reticularis, aPL-associated nephropathy, cardiac valve disease, cognitive dysfunction, and skin ulcers (1, 3). APS can occur in isolation (primary APS) or in association with other autoimmune diseases, most notably systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (4).Patients with positivity for aPLs can have heterogeneous clinical manifestations, including asymptomatic aPL positivity (no thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity), thrombotic APS (which is characterized by venous, arterial, or microvascular involvement), and obstetric APS (which is characterized by pregnancy complications such as fetal loss, recurrent early miscarriages, placental insufficiency, or preeclampsia). Furthermore, not every positive result for aPL testing is clinically significant, and transient low titer aPL positivity may occur in settings of infection or malignancy (5, 6). Despite accumulating data showing an important role for aPL laboratory profiles in APS assessment (7–9), the risk of aPL-related clinical events by aPL laboratory profile remains under investigation. Few large cohorts have estimated the prevalence of aPL-related clinical manifestations (10–12). Furthermore, the distribution of demographic and clinical factors by aPL-related clinical subtypes or laboratory profiles is not well-established.

The Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking (APS ACTION) is an international network established in 2010 to conduct large-scale multicenter studies and clinical trials in persistently aPL-positive patients (2). The APS ACTION clinical database and repository (“registry”) was created to study the natural course of persistently aPL-positive patients with or without autoimmune disorders. See Appendix A for APS ACTION registry investigators and their locations. In the present study, our primary objective was to retrospectively evaluate the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of aPL-positive patients enrolled in the APS ACTION registry since 2010, overall and by clinical subtype (aPL positive without APS classification, thrombotic APS, and obstetric APS). Secondly, we also assessed the clinical characteristics of aPL-positive patients who were tested at baseline for all three “criteria” aPLs (LAC, aCLs, and anti-β2GPI antibodies), categorized by aPL profile (LAC positivity only and single, double, and triple aPL positivity).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

APS ACTION registry and data collection

The inclusion criteria for the APS ACTION Registry were the following: individuals ages 18 to 60 years with persistent positivity for aPLs (at least 12 weeks apart) according to the revised Sapporo criteria (1), within 12 months prior to screening. Patients referred to APS ACTION sites were referred from hospital or outpatient settings and had received aPL testing for a variety of reasons such as thrombosis, pregnancy morbidity, false-positive serologic test for syphilis, prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombocytopenia, or concomitant systemic autoimmune diseases. As part of the registry entry criteria, patients must have had persistent aPL positivity prior to registry entry. Positivity for aCLs and/or anti-β2GPI antibodies was defined as an individual having IgG, IgM, or IgA titers of ≥40 units/ml (medium-to-high titers). LAC activity was detected by coagulation assays according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection (13).

An international web-based application, REDCap, was used to store and manage data on baseline sociodemographic information, aPL-related clinical events, pregnancy history, medications, and laboratory profile (14). Blood samples were also collected at registry entry for confirmation of aPL positivity. Patients were followed every 12 ± 3 months with clinical data and blood collection, or at the time of a new aPL-related thrombosis and/or pregnancy morbidity.

Study cohort

All participants who were persistently positive for aPLs and who were enrolled in the APS ACTION registry between May 2010 and March 2019 were included in the study cohort. We categorized patients into two groups by clinical subtype at baseline—1) patients who had positivity for aPLs without APS and who met laboratory criteria for APS classification, but not the clinical revised Sapporo criteria (1) and 2) patients with overall APS who met both laboratory and clinical criteria for definite APS. Patients with overall APS were further categorized into three mutually exclusive groups as follows: 1) patients with thrombotic APS, which is defined by a history of any vascular event (including any arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, or microvascular involvement, but excluding only superficial vascular thrombosis); 2) patients with obstetric APS, which is defined by a history of any pregnancy morbidity event (defined by the revised Sapporo classification criteria [1]); and 3) patients with thrombotic APS/obstetric APS, who were defined as individuals who have experienced any vascular thrombosis event and any pregnancy morbidity event (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with positivity for aPLs between different groups of aPL-positive patients included in the APS ACTION registry according to aPL-related clinical phenotype (2010–2019)*

| All patients, (N = 804) | Patients with aPL positivity without APS, 162 (20) | Patients with APS (overall), 642 (80) | Patients with OAPS only, 74 (9) | Patients with TAPS only, 446 (55) | Patients with TAPS + OAPS, 122 (15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary aPL/APS | 516 (64) | 89 (55) | 427 (67) | 55 (74) | 295 (66) | 77 (63) |

| Concomitant systemic autoimmune disease† | 288 (36) | 73 (45) | 215 (33) | 19 (26) | 151 (34) | 45 (37) |

| SLE | 242 (30) | 60 (37) | 182 (28) | 15 (20) | 129 (29) | 38 (31) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age at registry entry, mean ± SD years | ||||||

| 45.12 ± 13 | 43.80 ± 13 | 45.45 ± 13 | 41.47 ± 11 | 46.69 ± 14 | 43.34 ± 12 | |

| Female sex | 594 (74) | 127 (78) | 467 (73) | 74 (100) | 271 (61) | 122 (100) |

| Race‡ | ||||||

| White | 546 (68) | 118 (73) | 428 (67) | 52 (70) | 305 (68) | 71 (58) |

| Latin American Mestizos | 87 (11) | 6 (4) | 81 (13) | 6 (8) | 47 (11) | 28 (23) |

| Asian | 56 (7) | 17 (10) | 39 (6) | 8 (11) | 24 (5) | 7 (8) |

| Black | 26 (3) | 7 (4) | 19 (3) | 2 (3) | 12 (3) | 5 (4) |

| American Indian or Alaskan | 2 | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Native American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reported as “other”§ | 14 (2) | 2 (1) | 12 (2) | 1 (1) | 9 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Ethnicity¶ | ||||||

| US, Canada, and Europe | 377 (47) | 92 (57) | 285 (44) | 43 (58) | 201 (45) | 41 (34) |

| Non-Hispanic | 356 (44) | 88 (54) | 268 (42) | 38 (51) | 194 (43) | 36 (30) |

| Hispanic | 21 (3) | 4 (2) | 17 (3) | 5 (7) | 7 (2) | 5 (4) |

| South America | 137 (17) | 8 (5) | 129 (20) | 8 (11) | 82 (18) | 39 (32) |

| Mestizos | 72 (9) | 2 (1) | 70 (11) | 4 (5) | 42 (9) | 24 (20) |

| Caucasian | 47 (6) | 4 (2) | 43 (7) | 2 (3) | 31 (7) | 10 (8) |

| African descendent | 18 (2) | 2 (1) | 16 (2) | 2 (3) | 9 (2) | 5 (4) |

| Other# | 135 (17) | 35 (22) | 100 (16) | 16 (22) | 65 (15) | 19 (16) |

| Australia | 4 (1) | 0 | 4 (1) | 0 | 2 | 2 (2) |

| Not Aboriginal | 4 (1) | 0 | 4 (1) | 0 | 2 | 2 (2) |

| Aboriginal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Europe | 387 (48) | 84 (52) | 303 (47) | 37 (50) | 221 (50) | 45 (37) |

| North America | 232 (29) | 60 (37) | 172 (27) | 23 (31) | 117 (26) | 32 (26) |

| US | 201 (25) | 56 (35) | 145 (23) | 21 (28) | 95 (21) | 29 (24) |

| Canada | 31 (4) | 4 (2) | 27 (4) | 2 (3) | 22 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Latin America | 131 (16) | 6 (4) | 125 (19) | 7 (9) | 83 (19) | 35 (29) |

| Asia Pacific | 54 (7) | 12 (7) | 42 (7) | 7 (9) | 25 (6) | 10 (8) |

| Clinical manifestations | ||||||

| Any vascular event | 568 (71) | 0 | 568 (71) | 0 | 446 (100) | 122 (100) |

| Any arterial thrombosis | 300 (37) | 0 | 300 (37) | 0 | 239 (54) | 61 (50) |

| Stroke | 165 (21) | 0 | 165 (26) | 0 | 127 (28) | 38 (31) |

| Transient ischemic attacks | 69 (9) | 0 | 69 (11) | 0 | 50 (11) | 19 (16) |

| Myocardial infarction | 31 (4) | 0 | 31 (5) | 0 | 29 (7) | 2 (2) |

| Intracardiac thrombus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 (1) |

| Peripheral artery** | 30 (4) | 0 | 30 (5) | 0 | 27 (6) | 3 (3) |

| Visceral | 10 (1) | 0 | 10 (2) | 0 | 9 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Retinal | 5 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 | 3 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Any venous thrombosis | 347 (43) | 0 | 347 (54) | 0 | 269 (60) | 78 (64) |

| Central venous sinus | 13 (2) | 0 | 13 (2) | 0 | 12 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 76 (9) | 0 | 76 (12) | 0 | 64 (14) | 12 (10) |

| Upper extremity | 7 (1) | 0 | 7 (1) | 0 | 7 (2) | 0 |

| Lower extremity | 217 (27) | 0 | 217 (34) | 0 | 177 (40) | 40 (33) |

| Visceral | 8 (1) | 0 | 8 (1) | 0 | 4 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Retinal | 6 (1) | 0 | 6 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 1 |

| Any microvascular involvement | 93 (12) | 3 (2) | 90 (14) | 2 (3) | 67 (15) | 21 (17) |

| Biopsy-proven | 32 (4) | 0 | 32 (5) | 0 | 26 (6) | 6 (5) |

| Kidney | 15 (2) | 0 | 15 (2) | 0 | 11 (2) | 4 (3) |

| Skin | 9 (1) | 0 | 9 (1) | 0 | 9 (2) | 0 |

| Pulmonary | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Other | 5 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 | 3 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Clinical suspicion, no biopsy | 61 (8) | 3 (2) | 58 (9) | 2 (3) | 41 (9) | 15 (12) |

| Kidney | 14 (2) | 0 | 14 (2) | 2 (3) | 10 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Skin | 37 (5) | 3 (2) | 34 (5) | 0 | 24 (5) | 10 (8) |

| Pulmonary | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Other | 8 (1) | 0 | 8 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Both arterial and venous thrombosis | 92 (11) | 0 | 92 (14) | 0 | 72 (16) | 20 (16) |

| Recurrent vascular events (arterial and/or venous) | ||||||

| 225 (28) | 0 | 225 (35) | 0 | 173 (39) | 52 (43) | |

| Catastrophic APS†† | 9 (1) | 0 | 9 (1) | 0 | 7 (2) | 2 (2) |

| History of pregnancy | 393/594 (66) | 70/127 (55) | 323 (50) | 74 (100) | 127/271 (47) | 122 (100) |

| Pregnancy morbidity | 196/393 (50) | 0 | 196/323 (61) | 74 (100) | 0 | 122 (100) |

| Unexplained fetal death at 10 weeks of gestation or later | ||||||

| 136/196 (69) | 0 | 136/196 (69) | 51/74 (69) | 0 | 85/122 (70) | |

| Premature birth prior to 34 weeks of gestation due to eclampsia, preeclampsia, or placental insufficiency | ||||||

| 68/196 (35) | 0 | 68/196 (35) | 25/74 (34) | 0 | 43/122 (35) | |

| ≥3 unexplained spontaneous abortions prior to 10 weeks of gestation | 34/196 (17) | 0 | 34/196 (17) | 11/74 (15) | 0 | 23/122 (19) |

| 3 consecutive unexplained spontaneous abortions prior to 10 weeks of gestation | 29/196 (15) | 0 | 29/196 (15) | 9/74 (12) | 0 | 20/122 (16) |

| Other clinical manifestations‡‡ | 451 (56) | 76 (47) | 375 (58) | 30 (41) | 264 (59) | 81 (66) |

| Livedo reticularis/racemosa | 100 (12) | 10 (6) | 90 (14) | 8 (11) | 56 (13) | 26 (21) |

| Persistent thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/μl) | ||||||

| 151 (19) | 32 (20) | 119 (19) | 14 (19) | 75 (17) | 30 (25) | |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 40 (5) | 9 (6) | 31 (5) | 4 (5) | 22 (5) | 5 (4) |

| Cardiac valve disease | 65/688 (9) | 10/142 (7) | 56/546 (10) | 2/52 (4) | 34/391 (9) | 20/103 (19) |

| Skin ulcer | 50 (5) | 3 (2) | 47 (6) | 0 | 36 (6) | 11 (7) |

| aPL-associated nephropathy | 29/755 (4) | 0/156 (0) | 29/599 (5) | 2/69 (3) | 21/414 (5) | 6/116 (5) |

| Neurologic presentations | ||||||

| Cognitive dysfunction | 85 (11) | 11 (7) | 74 (12) | 3 (4) | 53 (12) | 18 (15) |

| MS-like disease | 6 (1) | 1 (1) | 5 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 |

| Chorea | 13 (2) | 2 (1) | 11 (2) | 0 | 7 (2) | 4 (3) |

| Seizure disorder | 67 (8) | 8 (5) | 59 (9) | 3 (4) | 42 (9) | 14 (11) |

| White matter lesions | ||||||

| 136/549 (25) | 17/103 (17) | 119/446 (27) | 6/35 (17) | 90/326 (28) | 23/85 (27) | |

| Medications (registry entry) | ||||||

| Any anticoagulation therapy | 497 (62) | 18 (11) | 479 (75) | 9 (12) | 372 (83) | 98 (80) |

| Warfarin | 434 (54) | 13 (8) | 421 (66) | 4 (5) | 328 (74) | 89 (73) |

| LMWH | 48 (6) | 4 (2) | 44 (7) | 5 (7) | 30 (7) | 9 (7) |

| Factor Xa inhibitor | 28 (3) | 1 (1) | 27 (4) | 0 | 26 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Thrombin inhibitor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) | 366 (46) | 108 (67) | 258 (40) | 52 (70) | 168 (38) | 38 (31) |

| Clopidogrel | 29 (4) | 2 (1) | 27 (4) | 1 (1) | 21 (5) | 5 (4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 364 (45) | 90 (56) | 274 (43) | 31 (44) | 189 (42) | 54 (44) |

| Statins | 191 (24) | 16 (10) | 175 (27) | 9 (12) | 143 (32) | 23 (19) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 163 (20) | 21 (13) | 142 (22) | 9 (12) | 106 (24) | 27 (22) |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin | 5 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 |

| Plasma exchange | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Rituximab | 16 (2) | 3 (2) | 13 (2) | 0 | 12 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Other immunosuppression§§ | 202 (25) | 42 (26) | 160 (25) | 10 (14) | 116 (26) | 34 (28) |

| No medications | 28 (3) | 16 (10) | 12 (2) | 9 (12) | 2 | 1 (1) |

| Medications (ever) | ||||||

| Any anticoagulation therapy | 763 (95) | 37 (23) | 566 (88) | 43 (58) | 407 (91) | 116 (95) |

| Warfarin | 526 (65) | 20 (12) | 506 (79) | 10 (14) | 388 (87) | 108 (89) |

| LMWH | 340 (42) | 21 (13) | 319 (50) | 41 (55) | 200 (45) | 78 (64) |

| Factor Xa inhibitor | 43 (5) | 2 (1) | 41 (6) | 1 (1) | 37 (8) | 3 (3) |

| Thrombin inhibitor | 4 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1) | 0 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) | 516 (64) | 121 (75) | 395 (62) | 63 (85) | 250 (56) | 82 (67) |

| Clopidogrel | 50 (6) | 3 (2) | 47 (7) | 1 (1) | 38 (9) | 8 (7) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 428 (53) | 101 (62) | 327 (51) | 34 (46) | 223 (50) | 70 (57) |

| Statins | 210 (26) | 20 (12) | 190 (30) | 9 (12) | 153 (34) | 28 (23) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 192 (24) | 23 (14) | 169 (26) | 11 (15) | 121 (27) | 37 (30) |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin | 57 (7) | 11 (7) | 46 (7) | 4 (5) | 35 (8) | 7 (6) |

| Plasma exchange | 16 (2) | 1 (1) | 15 (2) | 2 (3) | 8 (2) | 5 (4) |

| Rituximab | 48 (6) | 9 (6) | 39 (6) | 1(1) | 34 (8) | 4 (3) |

| Other immunosuppression§§ | 297 (37) | 57 (35) | 240 (37) | 18 (24) | 174 (39) | 48 (39) |

| No medications | 11 (1) | 9 (6) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Except where indicated otherwise, values are the number (%) of patients. Missing data and other categories are not included. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; aPLs = antiphospholipid antibodies; APS = antiphospholipid syndrome; APS ACTION = APS Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; LMWH = low molecular weight heparin; MS = multiple sclerosis; OAPS = obstetric APS; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; TAPS = thrombotic APS.

Systemic autoimmune diseases included SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, inflammatory muscle disease, and vasculitis.

Races were collected in a total of 731 patients (162 patients with aPL positivity only, 69 patients with OAPS, 403 patients with TAPS, and 97 patients with both TAPS and OAPS). Latin American Mestizo refers to a person of combined European and Indigenous American descent.

Includes American Indian or Alaskan, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and other unspecified races as indicated by the patient.

Ethnicities were collected in a total of 653 patients (146 patients with aPL positivity only, 65 patients with OAPS, 354 patients with TAPS, and 88 patients with both TAPS and OAPS).

Other unspecified ethnicities as indicated by the patient.

Consists of the arteries not in the chest or abdomen (i.e., in the arms, hands, legs, and feet).

Catastrophic APS was diagnosed as “probable” or “definite” based on the international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines for catastrophic APS (15).

Livedo reticularis/racemosa, persistent thrombocytopenia, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia, which patients were considered as “ever” or “never” having had these conditions at the time of registry entry.

Other immunosuppression treatment included azathioprine, glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and other therapies.

After categorizing patients into subgroups, we evaluated the baseline laboratory profiles of aPL-positive patients in the registry. We assessed the baseline clinical characteristics of aPL-positive patients with different laboratory profiles (single, double, and triple aPL positivity) among patients tested for all three aPLs (LAC, aCLs, and anti-β2GPI antibodies). We also subcategorized the subgroup with single aPL positivity by separately evaluating those with LAC only and those with single aPL positivity excluding LAC (Table 2). For the purposes of this study, positivity for aCL IgG, IgM, and IgA and anti-β2GPI IgG, IgM, and IgA was defined as a patient having a titer of ≥40 units, with the highest titer among all test results taken into consideration during analysis.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with aPL positivity in the APS ACTION registry (2010–2019) who were tested for 3 aPL, categorized according to aPL profile (N = 660)*

| LAC only positivity, 168 (25) | Positivity for any single aPL (including LAC only)†, 215 (32) | Single aPL positivity (excluding LAC only), 47 (7) | Double aPL positivity†, 167 (25) | Triple aPL positivity†, 278 (42) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any vascular events | 127 (73) | 148 (67) | 21 (45) | 118 (68) | 195 (70) |

| Arterial thrombosis | 61 (36) | 73 (34) | 12 (26) | 68 (41) | 96 (35) |

| Venous thrombosis | 81 (48) | 92 (43) | 11 (23) | 66 (40) | 132 (47) |

| Microvascular thrombosis | 10 (6) | 12 (6) | 2 (4) | 9 (5) | 16 (6) |

| Transient ischemic attacks | 11 (7) | 13 (6) | 2 (4) | 19 (11) | 20 (7) |

| Any pregnancy morbidity | 43/84 (51) | 53/108 (49) | 10/24 (42) | 41/86 (48) | 62/117 (53) |

| >1 fetal death at 10 weeks of gestation or later | |||||

| 31 (51) | 39 (52) | 8 (57) | 29 (53) | 43 (56) | |

| >1 preterm delivery prior to 34 weeks of gestation | |||||

| 12 (20) | 13 (17) | 1 (7) | 14 (25) | 29 (38) | |

| ≥3 pre-embryonic/embryotic losses prior to 10 weeks of gestation | |||||

| 9 (15) | 14 (19) | 5 (36) | 6 (11) | 6 (8) | |

| Any other clinical manifestation | 93 (55) | 107 (50) | 14 (30) | 104 (62) | 158 (57) |

| Livedo reticularis/racemosa | 27 (16) | 28 (13) | 1 (2) | 24 (14) | 32 (12) |

| Persistent thrombocytopenia† | 26 (15) | 30 (14) | 4 (9) | 29 (17) | 70 (25) |

| Hemolytic anemia‡ | 9 (5) | 10 (5) | 1 (2) | 7 (4) | 16 (6) |

| Cardiac valve disease | 11/146 (8) | 12/188 (6) | 1/42 (2) | 12/142 (8) | 32/234 (14) |

| Skin ulcers | 6 (4) | 7 (3) | 1 (2) | 7 (4) | 10 (4) |

| aPL-associated nephropathy | 4/157 (3) | 4/201 (2) | 0 | 5/160 (3) | 11/256 (4) |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 14 (8) | 17 (8) | 3 (6) | 20 (12) | 33 (12) |

| Multipe sclerosis–like disease | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 1 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Chorea | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 4 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Seizure | 17 (10) | 21 (10) | 4 (9) | 13 (8) | 23 (8) |

| White matter lesions | 33/120 (28) | 40/155 (26) | 7/35 (20) | 33/116 (28) | 45/190 (24) |

Except where indicated otherwise, values are the number (%) of patients. Patients in this analysis were tested for three aPLs (LAC, aCL, and anti-β2GPI antibodies). An additional 8 patients were tested for these three aPLs but had low titers (20–39 units) on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with negative LAC test, and were thus excluded from the analysis. Single aPL positivity was defined as positivity on one of the three aPL tests for aPLs, double aPL positivity was defined as positivity on two of three tests, and triple aPL positivity was defined as positivity on all three tests. All groups except LAC only and single aPL positivity were mutually exclusive. Only 5 (0.8%) of 660 patients had isolated aCL/anti-β2GPI IgA positivity with negative results for LAC and aCL/anti-β2GPI IgG and IgM. In total, 6 patients had catastrophic APS, distributed between double aPL– and triple aPL–positive groups. aCL = anticardiolipin antibody; anti-β2GPI = anti–β2-glycoprotein I; aPL = antiphospholipid antibody; APS = antiphospholipid syndrome; APS ACTION = APS Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking; LAC = lupus anticoagulant.

Cutoff value for aCL positivity and anti-β2GPI IgG, IgM, and IgA positivity was defined as a patient having a titer of at least 40 units upon antibody testing.

Defined as a platelet count of <100,000 per microliter tested twice at least 12 weeks apart.

Defined as anemia in the presence of antibodies directed against red blood cells, evidenced by either direct or indirect Coombs’ tests.

Data collection for baseline characteristics

Demographic characteristics collected included mean age, race (White, Latin American Mestizo, Asian, Black, or “Other”), ethnicity (Non–Latin American or Latin American [for the US, Canada, and Europe], Afro-descendent, Mestizo, or Caucasian [for South America], Afro-descendent [for South Africa], or “Other”), and region of residence (Europe, North America [for the US and Canada], Latin America, and Asia-Pacific). Clinical manifestations were subgrouped into vascular events (arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, microvascular involvement), catastrophic APS (CAPS), pregnancy morbidity, and “other.” Other clinical manifestations included livedo reticularis/racemosa, persistent thrombocytopenia defined as a platelet count of <100,000 per microliter tested twice at least 12 weeks apart, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, echocardiography-proven cardiac valve disease, aPL-related nephropathy, skin ulcers, chorea, seizure disorder, radiographic white matter lesions (only identified in those patients who had magnetic resonance imaging performed), and neuropsychiatric test–proven cognitive dysfunction (Supplementary Table 1, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.24468/abstract). CAPS was defined as “definite” or “probable” based on the international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines for CAPS (15). Past and current medications, including aspirin, warfarin, low molecular weight heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, rituximab, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil, were collected at the time of registry entry.

Study design and statistical analysis

Data from the APS ACTION registry were locked in March 2019. First, we evaluated the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of aPL-positive patients overall, and by clinical subtype: aPLs without APS, APS (overall), obstetric APS, thrombotic APS, and thrombotic APS/obstetric APS. We also classified aPL-positive patients (overall and by aPL-related clinical subtypes) as having primary aPL/APS or aPL/APS with other systemic autoimmune disease, including SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, inflammatory muscle disease, and vasculitis.

Second, we assessed the clinical characteristics of aPL-positive patients with different baseline laboratory profiles (LAC positivity only, single aPL positivity, single aPL positivity after excluding LAC positivity, double aPL positivity, and triple aPL positivity), among patients tested for all three aPLs. Descriptive statistics were used to describe continuous variables (mean ± SD, minimum, median, and maximum).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics in overall cohort

As of March 2019, 804 patients who were persistently positive for aPLs were enrolled from 26 centers worldwide (mean age of 45 ± 13 years at study entry, with 594 [74%] of patients being female, 546 [68%] being White, 87 [11%] being Latin American Mestizos, 387 [48%] from Europe, and 232 [29%] from North America). Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of aPL-positive patients at registry entry, both overall and by clinical subtype. In the study cohort, 642 (80%) of patients met the clinical criteria for definite APS; among these patients, 74 (12%) had obstetric APS only, 446 (69%) had thrombotic APS only, and 122 (19%) had both obstetric APS and thrombotic APS. One-hundred sixty-two patients (20%) did not meet the clinical criteria for definite APS; among these patients who have aPL positivity without APS, 76 (47%) had one or more other (non-criteria) clinical manifestations associated with aPLs, and 86 (53%) were asymptomatic. Thirty-six percent of the overall cohort had at least one concomitant systemic autoimmune disease, with 30% having SLE, 2% having Sjögren’s syndrome, 2% having mixed connective tissue disease, 1% having rheumatoid arthritis, 1% having vasculitis, 1% having systemic sclerosis, and 4% having other systemic autoimmune diseases. The frequency of systemic autoimmune diseases was slightly higher in the group that had aPL positivity without APS as compared to APS patients (45% and 33%, respectively).

Among the 804 registry participants, 568 (71%) experienced at least one vascular event (arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, or microvascular involvement), and 28% experienced recurrent vascular events. Venous thrombosis occurred more frequently than arterial thrombosis (43% versus 37%) in the overall cohort, with both types of thrombosis appearing in 11% of the cohort; 12% of the cohort had microvascular involvement, and 1% had CAPS. Among those with arterial thrombosis, strokes (21%) occurred much more frequently than cardiac events (4%); events in the lower extremities were the most common type of venous thrombosis (27%) recorded. Of the 393 women in the registry who had a history of pregnancy, 50% had experienced a pregnancy morbidity event, most commonly due to unexplained fetal death at ≥10 weeks of gestation (69%). Over half (56%) of the overall cohort had at least one non-criteria manifestation; among these, the most common were white matter lesions of the central nervous system and persistent thrombocytopenia.

In terms of medications that were being used at the time of registry entry, 62% of aPL-positive patients were receiving anticoagulation, with 54% receiving warfarin, 6% receiving low molecular weight heparin, and 3% receiving factor Xa inhibitor. Other commonly used medications were aspirin (46%), hydroxychloroquine (45%), and statins (24%).

Baseline characteristics by clinical subtype

When comparing characteristics by aPL-related clinical subtypes (Table 1), the incidence of concomitant systemic autoimmune disease was highest in patients with aPL positivity without APS (45%) and lowest in patients with obstetric APS (26%). A similar pattern was reflected in aPL-positive patients with concomitant SLE specifically (37% in patients who had aPL positivity without APS versus 20% in patients with obstetric APS). The mean age was lowest among patients with obstetric APS (41.47 ± 11 years) and highest among patients with thrombotic APS (46.69 ± 14 years). The majority of patients in each clinical subtype were White, whereas there were very few Black patients in each clinical subtype; the highest percentage of Latin American Mestizo patients were in the thrombotic APS/obstetric APS group (Table 1). Approximately 50% of patients in each clinical subtype were recruited from Europe, except in individuals with thrombotic APS/obstetric APS, which occurred less frequently in European patients (37%). Approximately 30% of thrombotic APS/obstetric APS patients were recruited from Latin America, which was the most common clinical subtype observed in recruited patients from this region.

Within the thrombotic APS group compared to the thrombotic APS/obstetric APS groups, while we observed similar frequencies of arterial thrombotic events (54% and 50%, respectively) and venous thrombotic events (60% and 64%, respectively) within the these subgroups, lower extremity venous thrombosis events were slightly higher among patients with thrombotic APS only compared to patients with both thrombotic and obstetric APS (40% and 33%, respectively) (Table 1). Between the thrombotic APS group and the thrombotic APS/obstetric APS group, we also observed a similar rate of microvascular involvement (15% and 17%, respectively) and catastrophic APS (2% each). When comparing pregnancy morbidity in patients with obstetric APS to that in patients with thrombotic APS/obstetric APS, we found similar frequencies of unexplained death of the fetus at 10 weeks of gestation or later (69% versus 70%, respectively), premature birth occuring earlier than 34 weeks of gestation due to eclampsia, pre-eclampsia or placental insufficiency (34% versus 35%, respectively), and at least 3 unexplained spontaneous abortions occuring prior to 10 weeks of gestation (15% versus 19%, respectively).

Compared to the overall cohort, patients who had aPL positivity without APS had a slightly lower rate of other clinical manifestations (47% versus 58%). Other clinical manifestations were highest in the thrombotic APS/obstetric APS group (66%) and lowest in the obstetric APS group (41%). In particular, patients with thrombotic APS/obstetric APS had substantially higher rates of livedo reticularis/racemosa, persistent thrombocytopenia, cardiac valve disease, skin ulcer, and cognitive dysfunction compared to patients with other subtypes of APS and the overall study cohort (Table 1). Thrombotic APS patients also had a higher rate of other clinical manifestations (59%) compared to obstetric APS patients (41%).

Compared to APS patients at the time of registry entry, patients who had aPL positivity without APS had higher rates of current use of aspirin (67% versus 40%) and hydroxychloroquine (56% versus 43%) and lower rates of anticoagulation, statin, and antihypertensive use. Aspirin use was highest in patients with a history of obstetric APS (70%) compared to patients with thrombotic APS (38%) or those with both thrombotic and obstetric APS (31%). A majority of APS patients had been receiving anticoagulation therapy with warfarin (66%) at the time of registry entry. Current use of any anticoagulation therapy (warfarin, low molecular weight heparin, factor Xa inhibitor, thrombin inhibitor) at registry entry was highest among patients with thrombotic APS (83%) compared to patients with aPL positivity without APS (11%). A similar pattern of medication use was observed for “ever” use at the time of registry entry among the aPL-related clinical subgroups (Table 1).

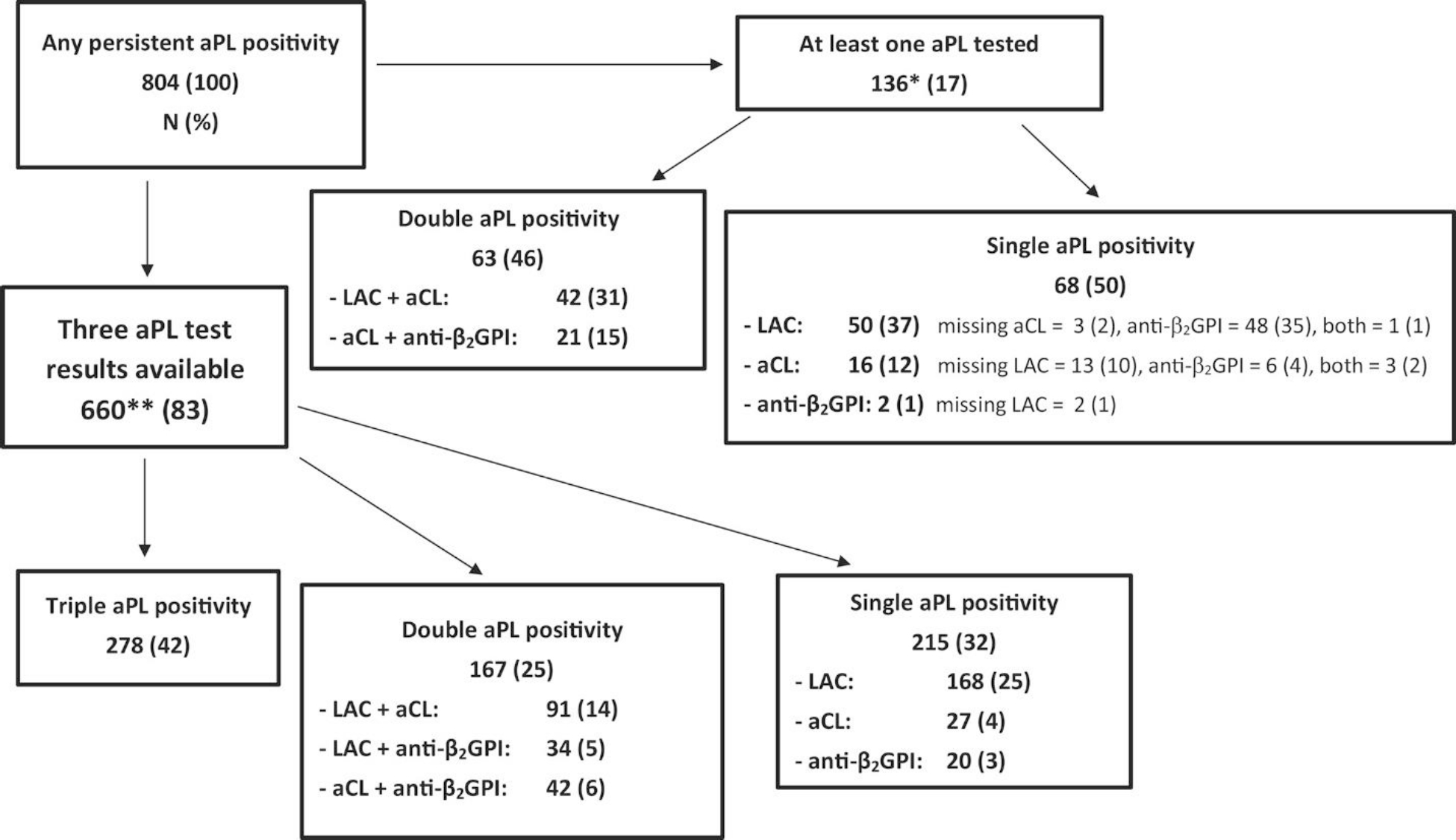

Baseline characteristics by aPL profile

Of the 804 aPL-positive patients, 660 (83%) were tested for all three aPLs (LAC, aCLs, and anti-β2GPI antibodies), and 42% had triple positivity for aPLs. We excluded eight patients who were tested for three aPLs but had low titers (20–39 units) of aPLs measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with negative LAC test. Approximately one-fifth (17%) of patients were missing at least one aPL test; in this group, the proportion with single positivity was similar to that with double positivity (50% and 46%, respectively). Among those without testing for the three aPLs and with single positivity only (50%), LAC positivity was most common (37%); the combination of LAC plus aCL positivity was more common than aCL plus anti-β2GPI antibody positivity in those with double aPL positivity (Figure 1).

Figure 1 -. Antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) profile at baseline in patients (n = 804) with persistent aPL positivity who were included in the Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking Registry.

* = Of 804 patients, 136 (17%) had missing data for their aPL profiles, with 38 (5%) patients lacking test results for LAC, 3 (0.3%) lacking test results for aCLs, 100 (12%) lacking test results for anti-β2GPI antibodies. ** = An additional 8 patients (1%) were tested for 3 aPLs but were excluded from the study due to low titers (20–39 units) on an aPL enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with negative LAC test. Anti-β2GPI = anti–β2-glycoprotein I; aCL = anticardiolipin antibody; LAC = lupus anticoagulant.

While similar frequencies of vascular thrombosis, pregnancy morbidity, and other clinical manifestations were observed across subgroups with single, double, and triple aPL positivity, the subgroup with single aPL positivity (excluding the patients with only LAC positivity) had substantially lower frequencies of all three event types (Table 2). Compared to the other aPL profile subgroups, triple aPL positivity had the highest proportion of patients with at least one preterm delivery before 34 weeks of gestation, persistent thrombocytopenia, aPL-related nephropathy, and cardiac valve disease. Within the group with single aPL positivity, LAC only positivity had the highest proportion of patients who experienced any vascular events, pregnancy morbidity, and other clinical manifestations (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Based on our multi-center international cohort of aPL-positive patients, 20% of patients who met the entry criteria did not fulfill classification criteria for clinical APS, 71% experienced vascular events, 50% of individuals with a history of pregnancy had aPL-related obstetric morbidity, and 56% had at least one non-criteria clinical aPL manifestation—most commonly thrombocytopenia and white matter lesions. Non-criteria clinical manifestations were highest in the thrombotic APS/obstetric APS group versus thrombotic APS or obstetric APS only. APS patients overall had higher rates of current anticoagulation therapy and statin use, but lower aspirin and hydroxychloroquine use than patients with aPL positivity without APS at registry entry. Compared to single–, double–, and triple–aPL-positive subgroups, the subgroup consisting of patients with single aPL positivity excluding LAC only had substantially lower frequencies of vascular events, pregnancy morbidity, and other clinical events; this suggests that LAC positivity appears to be a major contributor to aPL-related clinical features.

Our study adds to prior work demonstrating the clinical heterogeneity of aPLs, which can result in a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations. Although the current revised classification criteria for APS incorporates vascular events and pregnancy morbidity, various “non-criteria” manifestations, known to occur frequently in aPL-positive patients, were not included (16–18). Since then, various systematic res and meta-analyses in SLE patients have aimed to better characterize the role of aPL-related “non-criteria” manifestations, demonstrating an increased likelihood of cardiac valve disease, pulmonary hypertension, livedo reticularis, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and renal impairment in aPL-positive SLE patients compared to aPL-negative SLE patients (11, 19). Other investigators have assessed these manifestations in APS patients in the absence or presence of concomitant systemic autoimmune disease and have demonstrated increased rates of cognitive dysfunction, white matter lesions, aPL-related nephropathy, thrombocytopenia, and livedo reticularis among these individuals (10, 20). The present study adds to this literature by demonstrating that non-criteria manifestations, most commonly white matter lesions and thrombocytopenia, occurred in the majority (56%) of international aPL-positive patients and were more likely to occur in thrombotic APS/obstetric APS patients (66%), suggesting that non-criteria manifestations are prevalent in aPL-positive patients and potentially associated with more severe disease (20, 21). In fact, efforts are underway using cluster analysis methodology, a data-driven method that groups patients by combinations of aPL profiles and clinical features, to further identify clinical phenotypes and distinct “clusters” of patients enrolled in the APS ACTION registry (22, 23).

Assessment of clinical phenotypes, along with a better understanding of the role of aPL laboratory profiles, may play a critical role in risk stratification for aPL-positive patients (24). Although the definition of a “clinically significant” and “high-risk” aPL profile has not been clearly defined, different aPL profiles appear to confer different thrombosis risks (7, 25–27). Positive LAC test (compared to enzyme-linked immunosorbent testing for aCLs or anti-β2GPI antibodies), moderate-to-high (≥40 units) titers of aCLs or anti-β2GPI antibodies (compared to lower titers), IgG isotype (compared to IgM and IgA isotype), and triple positivity for aPLs (compared to single or double positivity for aPLs) have a stronger correlation with aPL-related clinical events (28–30). However, there is ongoing debate about the clinical significance of isolated LAC positivity and whether it is as important as triple aPL positivity. Additionally, one recent study demonstrated that aCL IgG, but not IgM, and LAC test positivity are associated with higher rates of thromboses in SLE patients (31). Our cross-sectional analysis, demonstrating a relatively similar frequency of aPL-related clinical events in single, double, and triple aPL positivity, and a substantially lower frequency in single aPL positivity patients without positive findings on LAC test, supports the association of clinical events with LAC positivity. Furthermore, while accumulating data show that LAC positivity may be a stronger risk factor for thrombosis and pregnancy morbidity compared to positivity for either aCLs or anti-β2GPI antibodies (1, 32), standardization of laboratory testing and cutoff thresholds are still needed (1). Prospective studies will determine the association between laboratory study levels and clinically relevant disease.

While anticoagulation is the mainstay in treatment of aPL-related clinical events in thrombotic APS (33), alternative treatments are needed in patients with refractory disease or microvascular APS (24, 34–39). Although the majority of APS patients overall received anticoagulation therapy, less than half received aspirin or immunosuppression treatment, and few received other treatments, such as intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, or rituximab. This finding may reflect an inherently low rate of refractory/microvascular APS or selection bias in our cohort. While data regarding treatment of obstetric APS are controversial in regard to the need for prophylactic low-dose aspirin versus the addition of unfractionated heparin to low-dose aspirin (40–44), the majority of patients in our cohort with obstetric APS only received aspirin (ever and at registry entry) and low molecular weight heparin (ever).

Furthermore, no clear consensus exists on primary prevention management of the symptoms of patients with persistent positivity for aPLs (45), including the use of aspirin, hydroxychloroquine, or anticoagulation therapy, although recent European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology guidelines suggest that low-dose aspirin may be beneficial for various patients who were aPL-positive (46). Our registry data show that the majority of patients who have aPL positivity without APS were treated with aspirin (67%) and hydroxychloroquine (56%), which may be driven by use of these medications for the prevention of thrombosis, underlying concomitant systemic autoimmune disease (45% of patients who have aPL positivity without APS), or other comorbid medical diseases, including cardiovascular risk factors. Patients who had positivity for aPLs without a diagnosis of APS had the highest percentage of concomitant SLE, which may have prompted aPL testing in this group.

Although we previously reported that LAC positivity, livedo reticularis, and cognitive dysfunction are more common in patients recruited from Brazil compared to those recruited from other parts of the world (47), the current study did not investigate specific clinical and laboratory differences by geographic region as a comprehensive regional analysis of the registry is already ongoing. Additionally, the low rate of Black patients (3–4%) in the registry may reflect selection bias (e.g., half of the patients were recruited from Europe) or disparities in access to care and would be worth investigation in future studies.

While the present study was limited in its retrospective, cross-sectional study design, we used data from a large, multi-center international patient cohort enriched with granular sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory, and medication information. Epidemiologic studies focusing on APS are limited; few large APS cohorts that are inclusive of different genders, races, and geographic regions are available to estimate the distribution of APS across clinical and laboratory subtypes. As data collection is ongoing in our registry, our data represents an interim assessment of baseline characteristics. Future analyses will use statistical testing and APS ACTION core laboratory aPL test results to evaluate significant differences between subgroups. Selection bias could be a factor in the low percentage of “other” clinical manifestations and systemic autoimmune disease in the obstetric APS group, as some patients in this group are recruited from obstetrics clinics. Our future prospective study will assess the risk of incident systemic autoimmune disease development after the diagnosis of primary obstetric APS.

Although selection and referral bias to APS “experts” should be considered in the interpretation of our registry data, our study demonstrated a low rate of CAPS or use of medications suggestive of refractory disease. Additionally, given that aPL profiles were not necessarily collected at the time of clinical events, our results should be confirmed in prospective studies. Moreover, while other “non-criteria” aPL tests such as those for anti–phosphatidylserine/prothrombin and anti–domain 1 antibodies, have increasingly shown to contribute to a diagnosis of APS and risk assessment for thrombosis (48, 49), our study did not evaluate these laboratory tests as they are not currently standardized or widely commercially available. Finally, although we did not stratify our cohort by those with or without an systemic autoimmune disease, in a previous analysis of APS ACTION registry patients, the frequencies of thrombosis and pregnancy morbidity were similar in aPL-positive patients in the absence or presence of concomitant SLE; however, SLE in patients with persistent aPL positivity was associated with increased frequency of thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, low complement, and positive findings for IgA anti–β2GPI antibodies (50).

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the heterogeneity of aPL-related clinical manifestations and laboratory profiles in a multicenter, international cohort of aPL-positive patients. Identification of APS patients by different clinical phenotypes and aPL profiles may improve risk stratification and help physicians and researchers better characterize the disease and understand clinical outcomes. Future prospective analyses, using standardized core laboratory aPL tests, will help clarify the role of aPL risk profiles.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE & INNOVATIONS.

Using the multicenter, international Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking (ACTION) registry, we described baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with persistent positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs), including 36% of patients with other systemic autoimmune disease included in this registry.

One-fifth of the registry patients did not fulfill clinical classification criteria for clinical APS. Among the registry patients, 71% experienced vascular events, 25% had aPL-related obstetric morbidity, and 56% had at least one other non-criteria clinical aPL manifestation, most commonly thrombocytopenia and white matter lesions of the central nervous system.

Although single–, double–, and triple–aPL–subgroups had similar frequencies of vascular, pregnancy, and non-criteria events, these events were less common in the single aPL subgroup after excluding LAC-positive patients, suggesting the importance of LAC positivity in APS.

Future prospective analyses, using standardized core laboratory testing for aPLs, will help clarify risk profiles for individuals with aPL positivity.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Fortin is recipient of a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair on systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is supported by NIH grant RO1-AR-069572 to Dr. Petri. Dr. Barbhaiya’s work is supported by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Investigator Award. The APS ACTION Registry was created using REDCAP, which was provided by the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College (CTSC grant UL1-TR000457).

APPENDIX A: THE APS ACTION INVESTIGATORS

Guillermo Pons-Estel (Santa Fe, Argentina), Bill Giannakopoulos, Steve Krilis (Sydney, Australia), Guilherme de Jesus, Roger Levy (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), Danieli Andrade (São Paulo, Brazil), Paul R. Fortin (Quebec City, Canada), Lanlan Ji, Zhouli Zhang (Beijing, China); Stephane Zuily, Denis Wahl (Nancy, France); Maria G. Tektonidou (Athens, Greece) Cecilia Nalli, Laura Andreoli, Angela Tincani (Brescia, Italy), Cecilia B. Chighizola, Maria Gerosa, Pierluigi Meroni (Milan, Italy), Vittorio Pengo (Padova, Italy), Savino Sciascia (Tulin, Italy), Karel De Ceulaer, Stacy Davis (Kingston, Jamaica), Olga Amengual, Tatsuya Atsum (Sapporo, Japan), Imad Uthman (Beirut, Lebanon) Maarten Limper, Philip de Groot (Utrecht, The Netherlands), Guillermo Ruiz Irastorza, Amaia Ugarte (Barakaldo, Spain), Ignasi Rodriguez-Pinto, Ricard Cervera (Barcelona, Spain), Esther Rodriguez, Maria Jose Cuadrado (Madrid, Spain), Maria Angeles Aguirre Zamorano, Rosario Lopez-Pedrera (Cordoba, Spain), Bahar Artim-Esen, Murat Inanc (Istanbul, Turkey), Maria Laura Bertolaccini, Hannah Cohen, Maria Efthymiou, Munther Khamashta, Ian Mackie, Giovanni Sanna (London, UK), Jason Knight (Ann Arbor, Michigan, US), Michelle Petri (Baltimore, Maryland, US), Robert Roubey (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, US), Tom Ortel (Durham, North Carolina, US), Emilio Gonzalez, Rohan Willis (Galveston, Texas, US), Michael Belmont, Steven Levine, Jacob Rand, Medha Barbhaiya, Doruk Erkan, Jane Salmon, Michael Lockshin (New York City, New York, US), and Ware Branch (Salt Lake City, Utah, US).

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Miyakis S, Lockshin M, Atsumi T, Branch D, Brey R, Cervera R, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4: 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbhaiya M, Andrade D, Bertolaccini M, Erkan D. Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking (APS ACTION). In: Erkan D, Lockshin MD, editors. Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Current Research Highlights and Clinical Insights. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 267–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine J, Branch, DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 752–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervera R, Serrano R, Pons-Estel G, Ceberio-Hualde L, Shoenfeld Y, Ramón E, et al. Morbidity and mortality in the antiphospholipid syndrome during a 10-year period: a multicentre prospective study of 1000 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 74: 1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Wahab N, Lopez-Olivio M, Pinto-Patarroyo G, Suarez-Almazor M. Systematic re of case reports of antiphospholipid syndrome following infection. Lupus 2016; 25: 1520–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinstein E, Shoenfeld Y. Antiphospholipid syndrome and cancer. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2007; 32: 184–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pengo V, Biasiolo A, Pegoraro C, Cucchini U, Noventa F, Iliceto S. Antibody profiles for the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome. Thromb Haemost 2005; 93: 1147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pengo V, Ruffatti A, Legnani C, Gresele P, Barcellona D, Erba N, et al. Clinical course of high-risk patients diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome. J Thromb Haemost 2010; 8: 237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yelnik C, Urbanski G, Drumez E, Sobanski V, Maillard H, Lanteri A, et al. Persistent triple antiphospholipid antibody positivity as a strong risk factor of first thrombosis, in a long-term follow-up study of patients without history of thrombosis or obstetrical morbidity. Lupus 2017; 26: 163–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cervera R, Piette J, Font J, Khamashta M, Shoenfeld Y, Camps M, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46: 1019–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ünlü O, Zuily S, Erkan D. The clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Rheumatol 2016; 3: 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, Amin S, Moder KG, Pruthi RK, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019; 71: 1545–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pengo V, Tripodi A, Reber G, Rand J, Ortel T, Galli M, et al. Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection. J Thromb Haemost 2009; 7: 1737–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde J. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Infor 2009; 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asherson R, Cervera R, de Groot P, Erkan D, Boffa M-C, Piette JC. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus 12: 530–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unlu O, Domingues V, de Jesús GR, Zuily S, Espinosa G, Cervera R, et al. Definition and epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome. In: Erkan D, Lockshin MD, editors. Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Current Research Highlights and Clinical Insights. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 147–69. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blank M, Cohen J, Toder V, Shoenfeld Y. Induction of anti-phospholipid syndrome in naive mice with mouse lupus monoclonal and human polyclonal anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88: 3069–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierangeli SS, Liu XW, Barker JH, Anderson G, Harris EN. Induction of thrombosis in a mouse model by IgG, IgM and IgA immunoglobulins from patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome. Thromb Haemost 1995; 74: 1361–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuily S, Wahl D. Pulmonary hypertension in antiphospholipid syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2015; 17: 478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tektonidou MG, Varsou N, Kotoulas G, Antoniou A, Moutsopoulos HM. Cognitive deficits in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: association with clinical, laboratory, and brain magnetic resonance imaging findings. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 2278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abreu MM, Danowski A, Wahl DG, Amigo MC, Tektonidou M, Pacheco MS, et al. The relevance of “non-criteria” clinical manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Technical Task Force Report on Antiphospholipid Syndrome Clinical Features. Autoimmun Rev 2015; 14: 401–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuily S, Clerc-Urmes I, Wahl D, Erkan D. Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking (APS ACTION) Clinical Database and Repository Cluster Analysis for Identification of Different Clinical Phenotypes Among Antiphospholipid Antibody-Positive Patients. Lupus 2016; 25: 74–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuily S, Clerc-Urmes I, Chighizola C, Baumann C, Wahl D, Meroni P, et al. Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking (APS ACTION) clinical database and repository cluster analysis for the identification of different clinical phenotypes among antiphospholipid antibody-positive female patients with a history of pregnancy. Lupus 2016; 25: 61.26306740 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia D, Erkan D. Diagnosis and management of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 2010–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finazzi G, Brancaccio V, Moia M, Ciavarella N, Mazzucconi MG, Schinco P, et al. Natural history and risk factors for thrombosis in 360 patients with antiphospholipid antibodies: a four-year prospective study from the Italian registry. Am J Med 1996; 100: 530–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gresele P, Migliacci R, Vedovati MC, Ruffatti A, Becattini C, Facco M, et al. Patients with primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and without associated vascular risk factors present a normal endothelial function. Thromb Res 2009; 123: 444–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuily S, de Laat B, Mohamed S, Kelchtermans H, Shums Z, Albesa R, et al. Validity of the global anti-phospholipid syndrome score to predict thrombosis: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54: 2071–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustonen P, Lehtonen KV, Javela K, Puurunen M. Persistent antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) in asymptomatic carriers as a risk factor for future thrombotic events: a nationwide prospective study. Lupus 2014; 23: 1468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wahl DG, Guillemin F, Maistre E de, Perret C, Lecompte T, Thibaut G. Risk for venous thrombosis related to antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Lupus 1997; 6: 467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuily S, Regnault V, Selton-Suty C, Eschwege V, Bruntz J-F, Bode-Dotto E, et al. Increased risk for heart valve disease associated with antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: meta-analysis of echocardiographic studies. Circulation 2011; 124: 215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Domingues V, Magder LS, Petri M. Assessment of the independent associations of IgG, IgM and IgA isotypes of anticardiolipin with thrombosis in SLE. Lupus Sci Med 2016; 3:e000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockshin M, Kim M, Laskin C, Guerra M, Branch D, Merrill J, et al. Prediction of adverse pregnancy outcome by the presence of lupus anticoagulant, but not anticardiolipin antibody, in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 2311–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erkan D, Aguiar CL, Andrade D, Cohen H, Cuadrado MJ, Danowski A, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force Report on Antiphospholipid Syndrome Treatment Trends. Autoimmunity Res 2014; 13: 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards MH, Pierangeli S, Liu X, Barker JH, Anderson G, Harris EN. Hydroxychloroquine reverses thrombogenic properties of antiphospholipid antibodies in mice. Circulation 1997; 96: 4380–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuri E, Taraborelli M, Andreoli L, Tonello M, Gerosa M, Calligaro A, et al. Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine reduces antiphospholipid antibodies levels in patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Immunol Res 2017; 65: 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erkan D, Vega J, Ramón G, Kozora E, Lockshin MD. A pilot open-label phase II trial of rituximab for non-criteria manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65: 464–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elazary AS, Klahr P, Hershko A, Dranitzki Z, Rubinow A, Naparstek Y. Rituximab induces resolution of recurrent diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in a patient with primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Lupus 2011; 21: 438–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lonze BE, Zachary AA, Magro CM, Desai NM, Orandi BJ, Dagher NN, et al. Eculizumab prevents recurrent antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and enables successful renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 2014; 14: 459–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zapantis E, Furie R, Horowitz D. Response to eculizumab in the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 341.24285491 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rai R, Cohen H, Dave M, Regan L. Randomised controlled trial of aspirin and aspirin plus heparin in pregnant women with recurrent miscarriage associated with phospholipid antibodies (or antiphospholipid antibodies). BMJ 1997; 314: 253–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutteh WH. Antiphospholipid antibody-associated recurrent pregnancy loss: treatment with heparin and low-dose aspirin is superior to low-dose aspirin alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 1584–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farquharson RG, Quenby S, Greaves M. Antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy: a randomized, controlled trial of treatment. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100: 408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laskin CA, Spitzer KA, Clark CA, Crowther MR, Ginsberg JS, Hawker GA, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and aspirin for recurrent pregnancy loss: results from the randomized, controlled HepASA Trial. J Rheumatol 2009; 36: 279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munoz-Rodriguez FJ, Font J, Cervera R, Reverter JC, Tassies D, Espinosa G, et al. Clinical study and follow-up of 100 patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29: 182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuo Y, Barbhaiya M, Erkan D. Primary thrombosis prophylaxis in persistently antiphospholipid antibody-positive individuals: where do we stand in 2018? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2018; 20: 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, Amoura Z, Cervera R, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: 1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ugolini-Lopes M, Rosa R, Nascimento I, R de Jesus G, Levy R, Erkan D, et al. , on behalf of APS ACTION registry. APS ACTION clinical database and repository analysis: primary antiphospholipid syndrome in Brazil versus other regions of the world [abstract]. Lupus 2016; 25 Supp 1S: 76. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sciascia S, Murru V, Sanna G, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. Clinical accuracy for diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: evaluation of 23 possible combinations of antiphospholipid antibody specificities. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10: 2512–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pengo V, Ruffatti A, Tonello M, Cuffaro S, Banzato A, Bison E, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome: antibodies to Domain 1 of beta2-glycoprotein 1 correctly classify patients at risk. J Thromb Haemost 2015; 13: 782–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unlu O, Erkan D, Barbhaiya M, Andrade D, Nascimento I, Rosa R, et al. The impact of systemic lupus erythematosus on the clinical phenotype of antiphospholipid antibody-positive patients: results from the AntiPhospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and InternatiOnal clinical database and repository. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019; 71: 134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.