Abstract

A variety of 17α-triazolyl and 9α-cyano derivatives of estradiol were prepared and evaluated for binding to human ERβ in both a TR-FRET assay, as well as ERβ and ERα agonism in cell-based functional assays. 9α-Cyanoestradiol (5) was nearly equipotent as estradiol as an agonist for both ERβ and ERα. The potency of the 17α-triazolylestradiol analogs is considerably more variable and depends on the nature of the 4-substituent of the triazole ring. While rigid protein docking simulations exhibited significant steric clashing, induced fit docking providing more protein flexibility revealed that the triazole linker of analogs 2d and 2e extends outside of the traditional ligand binding domain with the benzene ring located in the loop connecting helix 11 to helix 12.

Keywords: Estrogen receptor agonist, Oxidative benzylic cyanation, Alkyne-azide cycloaddition, Induced fit docking

1. Introduction

Estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and estrogen receptor-β (ERβ) belong to the nuclear hormone family of intracellular receptors, which are responsible for binding the endogenous estrogen, 17β-estradiol, along with estrone. The two receptors have different tissue distribution, as well as transcriptional activities. Upon binding of estradiol, ERβ activation can exert beneficial effects for the prostate, colon, and brain. ERβ is a target for agonist-based drug leads to treat a range of indications including depression,1 anxiety,2 and dementia.3 In contrast, ER-positive breast cancer, which proliferates in response to E2 necessitates treatment with ERα selective antagonists such as tamoxifen.4

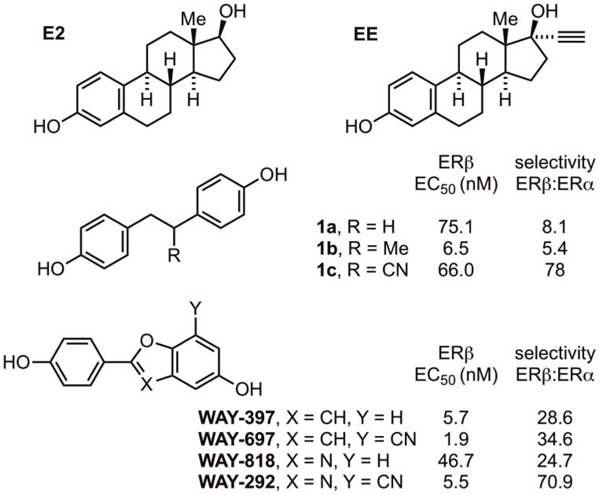

A number of selective estrogen receptor-beta agonists (SERBAs) have been reported, in particular 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl))diarylpropionitrile (DPN, 1c, Figure 1),5 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)benzofurans (WAY-397/WAY697) and 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazoles (WAY-818/WAY-292).6 The introduction of a cyano group at either a benzylic position or meta to the heterocyclic phenol group generally increases the ERβ agonism potency and selectivity for ERβ over ERα.

Figure 1.

As part of our interest in SERBAs,9 we have prepared a series of 17α-triazolyl and 9α-cyano estradiol analogs and evaluated these as potential agonists.

Ethynylestradiol (EE, Figure 1) is a synthetic estrogen widely used in oral birth control formulations,7 which exhibits greater affinity for either ERα or ERβ compared to E2.7b A variety of 17α-triazolyl estradiol analogs have been prepared from EE via Cu-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition,8 including EE-peptidomimetic conjugates which modulate ERα,8a,b EE-histone deacetylase conjugates,8c bivalent homodimeric estradiol ligands for targeted imaging,8d EE-BODIBY conjugates for potential in vivo imaging of ER-positive tumors,8e and EE–trilobolide conjugates with potential anti-cancer activity.8f In general, the 17α-triazolyl estradiol analogs exhibit poorer binding affinity than the parent EE (3–1000 fold less potent). The ERα vs. ERβ selectivity was reported in only two of these cases and this was found to vary depending on the substituent(s) on the triazolyl ring.8c,f

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Compound synthesis

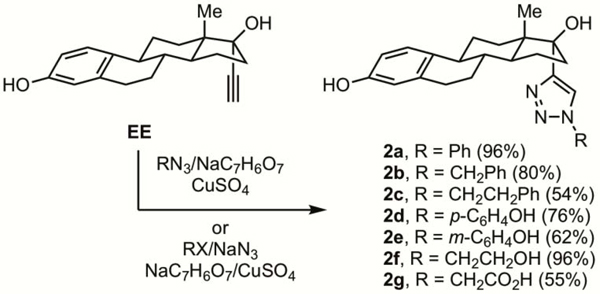

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (EE) with aryl or benzyl azides, 2-azidoethanol, or 2-azidoacetic acid under standard cycloaddition reaction conditions10 gave the disubstituted triazoles 2a-b and 2d-g in moderate to excellent yield (Scheme 1). In addition, three component coupling11 of EE, (2-bromoethyl)benzene and sodium azide gave 2c. The structure of 2b was identified by comparison of its NMR spectral data with that of the known compound.12 The 1,4-substituent pattern about the triazole ring of 2a-b, 2d-g was assigned on the basis of their NMR data. In particular, a signal in their 13C NMR spectra in the range of 119.2–121.0 ppm was assigned to the C5’ carbon of the triazole ring.13

Scheme 1.

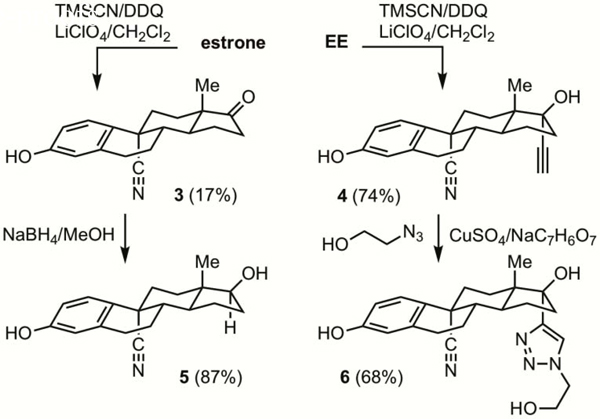

Oxidative cyanation14 of estrone or EE with DDQ and trimethylsilyl cyanide in the presence of lithium perchlorate gave 3 or 4 respectively (Scheme 2). Reduction of 3 gave 5, while cycloaddition of 4 with azido ethanol gave 6. The presence of the 9α-nitrile was substantiated by presence of a signal in the 13C NMR spectrum at ca. δ 122 ppm.14,15

2.2. Assaying

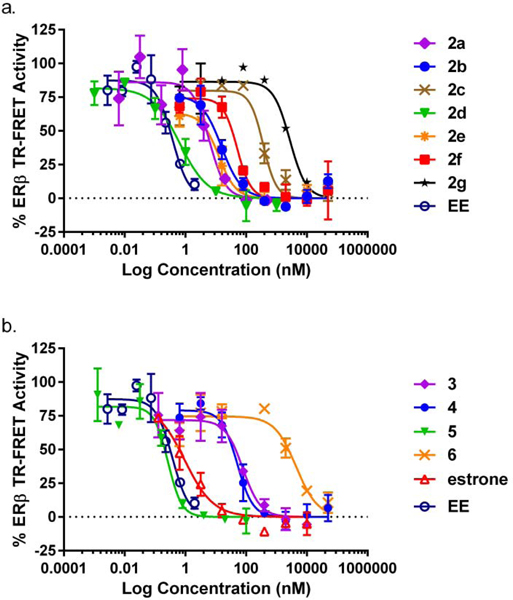

Compounds were initially screened in a TR-FRET binding assay which detects binding of the compound to the ligand binding domain (LBD) of ERβ via displacement of a fluorescent estrogen. All compounds synthesized were tested in a dose-response curve (Figure 2) and EC50 values are summarized in Table 1. Secondary assays were conducted for compounds with EC50 <100 nM in a cell-based transcription assay with full-length ERβ and ERα. For the 17α-triazolylestradiol analogs, the 4-(4-hydroxyphenyl) derivative 2d was the most potent (ERβ EC50 0.81 ± 0.29 nM), followed by the 4-phenyl derivative (2a, ERβ EC50 2.1 ± 1.1 nM), while the potency was nearly 80 times less for the 4-(3-hydroxyphenyl) derivative (2e). Extending the distance between the triazolyl and the phenyl ring by one methylene (2b) led to a 3.5-fold decrease in potency, while extending the separation by an ethylene spacer (2c) had a more dramatic decrease of 2 orders of magnitude. The ERβ:ERα selectivity of the 17a-triazolyl analogs was nearly non-existent, except for the 4-(2-hydroxyethyl) analog (2f, 9.3 fold selectivity for ERβ over ERα). The 9α-cyanoestradiol (5) was found to be the most potent (ERβ EC50 = 0.03 ± 0.0007 nM) and most selective compound (13-fold selective for ERβ over ERα), nearly as potent as E2, demonstrating that a relatively non-bulky substituent at this position is readily tolerated in the binding pocket. This can be contrasted to 9α-methylestradiol which is only ~1/3 as potent in displacing radiolabeled E2 from the rat uterus cytoplasmic estrogen receptor.16 However the 9α-cyano derivative (4) of ethynylestradiol (EE) exhibited ~2 orders of magnitude poorer potency compared to EE.

Figure 2. TR-FRET Estrogen Receptor Binding.

Binding assay for the ligand binding domain (LBD) of ERβ (see Table 1 for EC50 values) (a) 17α-triazolyl analogs; (b) 9α-cyano analogs.

Table 1.

Estrogen receptor assay data

| TR-FRET EC50 | Cell-based transcription assay EC50 (nM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Compd | ERβ (nM) | ERβ agonist | ERβ antagonist | ERβ agonist | ERα antagonist | selectivity |

|

| ||||||

| estrone | 0.94 ± 0.56 | 0.50 ± 0.15 | >10 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | >50 | 4.8 |

| E2 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | 0.022 ± 0.05 | – | 0.31 ± 0.03 | – | 14.1 |

| EE | 0.37 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | >10 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | >50 | 1.9 |

| 2a | 6 ± 2a | 2.1 ± 1.1 | >10,000 | 5 ± 1 | >1,000 | 2.4 |

| 2b | 15 ± 4 | 7.4 ± 1.8 | >10,000 | 7.1 ± 1.6 | >1,000 | 0.96 |

| 2c | 360 ± 70a | 240 ± 110 (~60%) | >10,000 | – | – | – |

| 2d | 0.65 ± 0.20 | 0.81 ± 0.29 | >10,000 | 0.87 ± 0.38 | >10,000 | 1.1 |

| 2e | 12 ± 3a (60%) | 21 ± 18 | >10,000 | 68 ± 9 (46%) | >1,000 | 3.2 |

| 2f | 50 ± 13 | 16 ± 3 | >10,000 | 149 ± 20 | >10,000 | 9.3 |

| 2g | 2800 ± 500a | 490 ± 100 | >10,000 | – | – | – |

| 3 | 78 ± 19 | 9 ± 6 | >5,000 | 88 ± 11 | >10,000 | 9.8 |

| 5 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 0.029 ± 0.007 | >25 | 0.38 ± 0.053 | >5,000 | 13.1 |

| 4 | 51 ± 11 | 14 ± 7 | >10,000 | 22 ± 4 | >10,000 | 1.57 |

| 6 | 4,400 ± 1,300 | – | – | – | – | – |

TR-FRET assay with 2× fluormone, to obtain satisfactory Z’, without affecting EC50 since fluormone is present as a tracer

2.3. Docking Studies

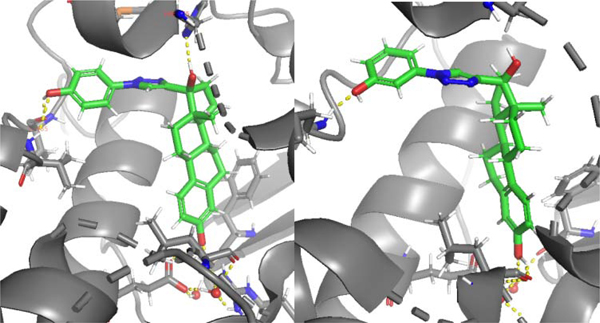

Rigid docking simulations using Maestro Glide were unsuccessful at docking several ligands due to the lack of protein flexibility.17 CCDC GOLD docking software was able to complete the docking simulation in a rigid protein simulation however the outputs generated exhibited significant steric clashing. Since the compounds were experimentally proven to bind within the Estrogen Receptor ligand binding domain, methods were refined until an acceptable simulation was obtained.17 Glide Induced Fit Docking, within Schrödinger Suites, introduced more protein flexibility in the simulation and allowed for the successful docking of agonist compounds. Validation of the induced fit docking procedure for ERβ (PDB 2JJ3) was conducted using the ligands (3aS,4R,9bR)-1,2,3,3a,4,9b-hexahydro-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(methoxymethyl)cyclopenta[c][1]benzopyran-8-ol (originally present in crystal structure PDB 2JJ3) and E2, which generated poses and interactions similar to that observed in the crystal structures.18

Docking of 9α-cyanoestradiol (5) into ERβ revealed that this molecule binds nearly identically to estradiol, also engaging in hydrogen bonding interactions with Glu305 and His475, and pipi stacking with Phe356 (see Figure S1). These three interactions together are well documented in causing agonist activity for small molecule ligands.19 These computational results are consistent with the nearly equal potency of 5 compared to E2. Poor binding was observed experimentally for compound 3, the 9α-nitrile analog of estrone. Docking simulations predict that this lack of potency is due to the removal of the hydrogen bond donor in this location, which results in the loss of hydrogen bonding with residue His475.

Induced fit docking simulations of the 17α-triazolyl estradiol analogs 2d and 2e (Figure 3) revealed that the steroidal framework of each is oriented similarly to that for estradiol. The interactions among the two molecules differed regarding the triazole linker orientation and interactions extending outside of the traditional ligand binding domain. The triazole group is predicted to extend out of the traditional LBD along helix-11, with the benzene ring located in the loop connecting helix-11 to helix-12, which could affect the relative stability of the two known orientations of helix-12 that are associate with agonist versus antagonist activity. But, this location does not introduce any notable interactions with surrounding residues individually. Additionally, this region is significantly hydrophobic, and thus favorably allows the benzene ring within this pocket. The addition of a hydroxyl group onto the triazole-benzene ring affects the potency of the molecule depending upon its location. For 2d, docking computations predict hydrogen bonding of the (4-hydroxyphenyl) group attached to the triazolyl ring with Val485, located on helix-12. Otherwise a hydrophobic region that would not welcome a polar group, this hydrogen bond interaction with the Val485 backbone is hypothesized to be critical to agonist activity induced by the conformational change after binding, and that is associated with the 90 degree rotation of helix-12 relative to helix-11. Helix-12 is a highly rotatable group that either moves to reveal the coactivator binding groove (agonist activity) or remain covering the coactivator binding groove in its more energetically favorable position (antagonist activity), and any interactions in this region (one of the two helices, or the loop connecting them) can stabilize one conformation or the other. In terms of effects on affinity, the 17α-triazolyl analog 2e, possessing a (3-hydroxylphenyl) group attached to the triazole produced roughly a 100-fold decrease in potency. Docking studies of 2e suggest that the allowability of the triazole ring to rotate outward from the LBD, and aim the hydroxyl group toward solvent and perhaps relieve steric or clash or electronic repulsion (yet gaining some solvation energy), causes this decrease in potency. The hydrophobic region that is favorable for a benzene ring is not necessarily favorable for the added and more polar hydroxyl group, and this positioning on the ring allows for rotation away from the hydrophobic pocket; and thus away from helix-12. Hydrogen bonding with residue Met479 stabilizes the shown orientation. This binding pose results in the loss of both hydrogen bonding and pi-pi stacking with His475 exhibited by 2d.

Fig. 3.

Docked structures of 17-(1-aryl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)estra-1,3,5(10-triene-3,17-diol)s 2d (left) and 2e (right) in the ERβ binding pocket.

3. Conclusion

The results of the present study demonstrate that introduction of a cyano group at C7 in α-orientation (i.e. 5) does not greatly diminish the agonism of this analog in either ERβ or ERα, compared to estradiol. Furthermore, the ERβ and ERα agonism of 19α-triazolyl analogs of estradiol (2a-g) are highly dependent on the nature of the substituent at C1 of the triazolyl ring, with a maximum ERβ:ERα selectivity of ~10 fold (2f). Computational modeling, using an induced fit docking protocol, suggest that the 19α-triazolyl substituent fits into a predominantly hydrophobic region and that further hydrogen bonding to backbone N–H bonds may play a role in the potency of these analogs.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. General experimental

All reactions involving moisture or air sensitive reagents were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere in oven-dried glassware with anhydrous solvents. THF and ether were distilled from sodium/benzophenone. Purifications by chromatography were carried out using flash silica gel (32–63 μ). NMR spectra were recorded on either a Varian Mercury+ 300 MHz or a Varian UnityInova 400 MHz instrument. CDCl3, CD3OD and d6-DMSO were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. 1H NMR spectra were calibrated to 7.27 ppm for residual CHCl3, 3.35 ppm for CD2HOD, or 2.49 ppm for d5-DMSO. 13C NMR spectra were calibrated from the central peak at 77.23 ppm for CDCl3, 49.3 ppm for CD3OD, or 39.7 ppm for d6-DMSO. Coupling constants are reported in Hz. Elemental analyses were obtained from Midwest Microlabs, Ltd., Indianapolis, IN, and high-resolution mass spectra were obtained from the COSMIC lab at Old Dominion University.

4.1.1 General procedure for triazole synthesis

To a solution of alkyne (1.00 mmol), sodium ascorbate (0.40 mmol), and copper (II) sulfate (0.20 mmol) in water/tBuOH (1:1, 10 mL) was added the desired azide (1.00 mmol). The solution stirred for 30 h. The reaction was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine (15 mL), dried (MgSO4), and concentrated. The resulting triazole compound was purified by column chromatography.

4.1.2. 17-(1-Phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-estra-1,3,5(10-triene-3,17-diol (2a)

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (100 mg, 0.337 mmol) with phenylazide (40 mg, 0.339 mmol) was carried out by the general procedure. Purification of the residue by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes–ethyl acetate = 1:1 to 100% ethyl acetate gradient) gave 2a (134 mg, 96%) as a colorless solid. mp 123125 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.31 (s, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.52–6.43 (m, 2H), 2.81–2.70 (m, 2H), 2.58–2.45 (m, 1H), 2.21–1.25 (m, 11H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 0.72 (dt, J = 3.0, 11.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ 156.5, 153.3, 137.6, 131.3, 129.8, 128.8, 126.5, 126.0, 120.8, 120.3, 114.8, 112.5, 82.1, 48.5, 47.3, 43.3, 40.0, 37.4, 33.2, 29.5, 27.6, 26.3, 23.5, 13.7 ppm. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 438.2150. C26H29N3O2Na+ requires 438.2152.

4.1.3. 17-[1-(Phenylmethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol (2b)

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (350 mg, 1.03 mmol) with benzylazide (142 mg, 1.07 mmol) was carried out by the general procedure. Purification of the residue by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane-ethyl acetate = 1:1 to 100% ethyl acetate gradient) gave 2b (354 mg, 80%) as a colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.36–7.27 (m, 6H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.57–6.51 (m, 1H), 5.53 (s, 2H), 2.87–1.25 (m, 15H), 0.98 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.1, 153.7, 138.0, 134.6, 132.1, 129.1, 128.7, 127.9, 126.3, 121.4, 115.4, 112.8, 82.4, 54.1, 48.4, 47.3, 43.2, 39.3, 37.8, 32.9, 29.6, 27.2, 26.2, 23.3, 14.2 ppm. The NMR spectral data for this compound were consistent with the literature values.12

4.1.4. 17-[1-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol (2d)

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (204 mg, 0.437 mmol) with 4-azidophenol (68 mg, 0.50 mmol) was carried out by the general procedure. Purification of the residue by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes–ethyl acetate = 1:1 to 100% ethyl acetate gradient) gave 2d (143 mg, 76%) as a light yellow solid. mp 185–189 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.93–6.86 (m, 3H), 6.48–6.41 (m, 2H), 2.78–2.67 (m, 2H), 2.17–1.18 (m, 12H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.79 (br t, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD) δ 159.5, 156.2, 155.9, 138.9, 132.6, 130.9, 127.3, 123.4, 122.2, 117.3, 116.1, 113.8, 83.4, 44.9, 41.1, 38.6, 34.5, 30.8, 28.8, 27.6, 24.8, 15.1 ppm [two signals obscured by CD3OD]. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 454.2098. C26H29N3O3Na+ requires 454.2101.

4.1.5. 17-[1-(3-Hydroxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol (2e)

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (105 mg, 0.354 mmol) with 3-azidophenol (60 mg, 0.44 mmol) was carried out by the general procedure. Purification of the residue by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes–ethyl acetate = 1:1 to 100% ethyl acetate gradient) gave 2e (95 mg, 62%) as a light yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 8.56 (s, 1H), 7.45–7.38 (m, 3H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 2.80–2.60 (m, 2H), 2.20–1.05 (m, 11H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 0.76 (br t, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, d6DMSO) δ 158.5, 155.3, 154.9, 137.8, 137.2, 130.8, 130.5, 126.1, 120.7, 115.4, 114.9, 112.7, 110.2, 106.7, 81.2, 47.8, 46.8, 43.2, 37.3, 32.8, 29.3, 27.2, 26.1, 23.6, 14.4 ppm [one signal obscured by d6-DMSO]. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 454.2098 C26H29N3O3Na+ requires 454.2101.

4.1.6. 17-[1-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol (2f)

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (148 mg, 0.499 mmol) with 2-azidoethanol (50 mg, 0.55 mmol) was carried out by the general procedure. Purification of the residue by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes–ethyl acetate = 1:1 to 100% ethyl acetate gradient) gave 2f (185 mg, 96%) as a light yellow solid. mp 183–200 °C (dec.); 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 9.10 (s, 1H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 5.30–5.20 (br s, 1H), 5.17 (t, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (br t, J = 4.4 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 3.98–3.89 (m, 2H), 2.95–2.79 (m, 2H), 2.30–1.28 (m, 10H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 0.77 (t, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, d6DMSO) δ 154.9, 153.9, 137.2, 130.5, 126.0, 123.1, 114.9, 112.7, 81.2, 60.0, 52.0, 47.5, 46.7, 43.2, 37.2, 32.6, 31.3, 29.3, 27.2, 26.1, 23.6, 14.4 ppm. Anal. calcd. for C22H29N3O3: C, 68.90; H, 7.62. Found: C, 68.77; H, 7.77.

4.1.7. 4-[(17b)-3,17-Dihydroxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-y]-1H-1,2,3-triazole-1-acetic acid (2g)

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (100 mg, 0.337 mmol) with 2-azidoacetic acid (35 mg, 0.35 mmol) was carried out by the general procedure. Purification of the residue by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes–ethyl acetate = 1:1 to 100% ethyl acetate gradient) gave 2g (74 mg, 55%) as a light yellow solid. mp 151–155 °C (dec.); 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 7.81 (s, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.43 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 2.80–2.60 (m, 2H), 2.40–1.10 (m, 15H), 0.95 (s, 3H), 0.62 (br t, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 179.7, 155.2, 154.4, 137.5, 130.8, 126.4, 124.4, 115.3, 113.1, 81.5, 70.3, 48.0, 47.1, 43.6, 37.6, 33.0, 29.7, 27.6, 26.5, 24.7, 24.0, 14.8 ppm. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 420.1891. C22H27N3O4Na+ requires 420.1894.

4.1.8. 17-[1-(2-Phenylethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]-estra1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol (2c)

To a stirring solution 2-bromoethyl benzene (0.05 mL, 0.3 mmol), sodium ascorbate (67 mg, 0.34 mmol), and sodium azide (0.027 g, 0.40 mmol) was added ethynylestradiol (100 mg, 0.337 mmol) and stirred at 65 °C overnight. Dilute NH4OH was then added and the resultant mixture was extracted several times with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes–ethyl acetate = 1:1) to afford 2c as a colorless solid (80 mg, 54%). mp 121–122.4 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.22–7.07 (m, 5H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (s, 1H), 4.72–4.53 (m, 2H), 3.19 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.79–2.69 (m, 2H), 2.45–2.33 (m, 1H), 2.15–1.73 (m, 5H), 1.52–1.24 (m, 6H), 0.96 (s, 3H), 0.42 (dt, J = 2.0, 11.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ 156.0, 154.9, 138.9, 138.8, 132.6, 123.0, 129.7, 127.9, 127.2, 124.5, 116.2, 113.9, 83.2, 52.4, 49.3, 48.2, 44.9, 41.1, 38.4, 37.5, 34.3, 30.9, 28.8, 27.6, 24.7, 15.0 ppm. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 466.2462. C28H33N3O2Na+ requires 466.2465.

4.1.9. General procedure for oxidative benzylic cyanation

Lithium perchlorate (208 mg, 2.0 mmol) and trimethylsilyl cyanide (1.25 mL) were stirred in CH2Cl2 (3.0 mL) for 5 min at room temperature. The deep red reaction mixture was then cooled to –10 °C in an acetone-ice bath, and a solution of estrone (531 mg, 2.0 mmol) in dichloromethane (3.0 mL) was added. Solid DDQ (490 mg, 2.2 mmol) was then added in five separate portions over the course of 30 min. After each addition of DDQ, the reaction mixture turned a deep blue. When the reaction mixture returned to a deep red color, the next portion of DDQ was added. Upon the final addition of DDQ, the reaction mixture stirred for 1 h at the reduced temperature before being quenched with 2N NaOH (2 mL) and 10% aqueous sodium thiosulfate (5 mL). This reaction mixture was extracted several times with CH2Cl2 and the combined extracts were washed with 10% aqueous sodium thiosulfate until the yellow color disappeared, and then by brine, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated.

4.1.10. 3-Hydroxy-17-oxo-estra,1,3,5(10)-triene-9-carbonitrile (3)

Purification of the residue by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes–ethyl acetate = 9:1 to 4:1 gradient) afforded 3 as a colorless solid (92 mg, 17%). mp >260 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 9.50 (s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.55 (s, 1H), 2.88–2.83 (m, 2H), 2.73–2.64 (m, 1H), 2.44 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 2.23–2.10 (m, 1H), 2.00–1.85 (m, 3H), 1.82–1.70 (m, 3H), 1.66–1.50 (m, 3H), 0.84 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 219.1, 157.6, 138.1, 127.6, 126.5, 122.7, 116.2, 114.5, 46.7, 47.8, 43.7, 35.8, 30.9, 29.7, 28.8, 23.3, 21.4, 14.0 ppm [one signal obscured by d6-DMSO].

4.1.11. (17α)-3,17-Dihydroxy-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-trien-20yne-9-carbonitrile (4)

The reaction of ethynylestradiol (300 mg, 1.02 mmol) following the general procedure was carried out. Purification of the crude product by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane–ethyl acetate = 1:1) gave 4 (242 mg, 74%) as a light yellow solid. Decomp = 146–152 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (s, 1H), 2.94–2.77 (m, 2H), 2.69–2.62 (m, 1H), 2.38–2.24 (m, 2H), 2.18 (qd, J = 3.8, 12.4 Hz, 1H), 1.95 (td, J = 3.6, 12.3 Hz, 1H), 1.86–1.64 (m, 7H), 1.40 (qd, J = 5.5, 12.2 Hz, 1H), 1.29–1.23 (m, 1H), 0.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.8, 137.8, 128.7, 126.7, 121.9, 120.7, 118.3, 86.2, 79.9, 74.9, 46.9, 45.3, 43.3, 41.1, 38.6, 31.6, 30.3, 28.8, 23.5, 22.4, 12.6 ppm. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 344.1621. C21H23NO2Na+ requires 420.1894.

4.1.12. 3,17-Dihydroxy-17-[1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-9-carbonitrile (6)

The reaction of 4 (150 mg, 0.367 mmol) with 2-azidoethanol was carried out by the general procedure in 4.1.1. Purification of the crude product by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane– ethyl acetate = 1:1) gave 6 (102 mg, 68%) as a light yellow solid. mp 222–237 °C (dec.); 1H NMR (300 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 9.49 (s, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 5.08 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (t, J = 5.4, 2H), 3.85–3.77 (m, 2H), 2.90–2.80 (m, 2H), 2.58–2.35 (m, 4H), 2.16–1.46 (m, 8H), 1.01–0.93 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 156.8, 153.4, 137.5, 126.8, 126.5, 122.9, 121.9, 115.5, 113.8, 80.9, 60.1, 51.9, 46.8, 43.8, 42.6, 40.8, 37.1, 30.8, 30.1, 28.4, 23.6, 23.1, 14.2 ppm. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 431.2019. C23H28N4O3Na+ requires 431.2054.

4.1.13. 3,17-Dihydroxy-estra,1,3,5(10)-triene-9-carbonitrile (5)

To a solution of 3 (61 mg, 0.21 mmol) dissolved in methanol (10 mL) at room temperature was added NaBH4 (9.0 mg, 0.24 mmol), and the reaction stirred for 24 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with an equal volume of water and extracted with several times with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layers were dried (MgSO4) and concentrated to give 5 as a colorless solid (53 mg, 87%). mp 168–170 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6DMSO) δ 9.41 (s, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (s, 1H), 4.62 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.57–3.47 (m, 1H), 2.84–2.76 (m, 2H), 2.60 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (s, 1H), 1.99 (s, 1H), 1.86 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 1.81–1.75 (m, 1H), 1.721.60 (m, 3H), 1.17 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 0.79 (s, 1H), 0.63 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 157.3, 137.9, 127.3, 126.6, 122.6, 115.9, 114.3, 46.2, 43.2, 34.4, 31.2, 30.0, 28.6, 23.7, 22.6, 21.2, 14.5, 11.5 ppm [one signal obscured by d6-DMSO]. HRMS (FAB): M + Na+, found 320.1620. C19H23NO2Na+ requires 320.1621.

4.3. Biological evaluation

4.3.1. TR-FRET Ligand Binding Displacement Assay

To determine the ability of compounds to bind to ERβ, the LanthaScreen® TR-FRET Competitive Binding assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. In this assay, the ERβ ligand-binding domain (LBD) was tagged with GST, and antiGST antibody was tagged with terbium, and estrogen was tagged with fluorescein. Some assays used twice the amount of suggested fluorescein-tagged estrogen (fluormone), as noted by a footnote in Table 1. This additional amount of fluormone was required to obtain satisfactory Z’. Control assays with E2 showed that doing so did not shift the EC50 of E2. The assay was set up in a 384-well low volume white plate (Corning® 4512) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the plate was spun at 1000 rpm for 1 min in a centrifuge with swing-out rotor (Eppendorf 5810, rotor A-4–64). Then the plate was read according to Thermo Fisher Scientific settings (excitation at 332 nm, emission wavelengths of 518 nm and 488 nm with 420 nm cutoff, 50 μs integration delay, 400 μs integration time, and 100 flashes per read) in a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices). The TR-FRET ratio of fluorescein (518 nm) over terbium (488 nm) emission was calculated by SoftMax Pro 6.2.2 (Molecular Devices). Data were analyzed using Prism 6 (GraphPad). Data were normalized to the TR-FRET ratio of 1% DMSO (negative) and 1 μM E2 (positive) controls and EC50 values were calculated by doing a nonlinear square fit of the data with the high concentrations of competing ligand constrained to zero. Standard deviations for the nonlinear least squares fit are reported. For replicate assays, the EC50 for curves that gave the median value are reported in Table 1.

4.3.4. Cell-based Agonist and Antagonist Assays

Kits from INDIGO Biosciences were used to examine the impact of compounds on agonist and antagonist activity for full-length, native ERβ and ERα. In this assay, a luciferase reporter gene was downstream from an ER-responsive promoter activated by an agonist. Antagonist assays tested if compound could block activation by E2 while agonist assays tested if compound could activate transcription. Chemiluminescence resulting from ER-induced luciferase expression was measured in a SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices). Stock solutions in DMSO were diluted to final concentrations in compound screening media such that DMSO was kept below 0.4%. Final concentrations varied depending on the potency of the compound and ranged from 10 μM to 1 nM. Vehicle and E2 controls were included in each assay. E2 had agonist activity IC50 values of 0.31 ± 0.03 nM and 0.022 ± 0.005 nM for ERα and ERβ, respectively. Kit instructions were followed. Briefly, cells were taken directly from the freezer and cell recovery media was added. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Half the cells were plated for agonist assays, while the other half had E2 added and were then plated for antagonist assays. Compound dilutions were then added to plated cells and the plate was incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 22–24 h. Media was removed and detection reagent was added before luminescence was read. Data were normalized to controls and EC50 values were calculated by doing a nonlinear squares fit using Prism 6 (GraphPad). Standard deviations are for the nonlinear fit.

4.4. Computational docking

Ligand structures were prepared using the LigPrep tool in Schrödinger Suite. The OPS3e force field was utilized to generate the most favorable conformations at a pH of 7.0 ± 2.0, and generating energy values using Ionizer. Specific chiralities were retained for conformational sampling of the ligands. Estrogen receptor beta crystal structure (PDB file: 2JJ35) was imported into the workspace and prepared using Schrödinger Protein Preparation Wizard. Once the protein was displayed in the workspace, all default settings in the import and process tab were retained. Additionally, missing side chains and missing loops were selected to be filled using Prime for the preprocessing of the protein. Under the Review and Modify tab section, the B chain and all associated water molecules and heteroatoms were deleted to create a more simplified docking model. The structure was then optimized and minimized to generate a final prepared protein structure of ERβ. Induced fit docking (IFD) was selected using the Browse task tool, bringing up the respective panel. On the receptor panel, the docking box center was selected as the cocrystallized ligand in the protein structure (3aS,4R,9bR)- 1,2,3,3a,4,9b-hexahydro-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(methoxymethyl)cyclopenta[c][1]benzopyran-8-ol (JJ3).6 The box size was adjusted to dock ligands with length less than 20Å. Under the Glide docking tab, side chains were trimmed by manually selecting residues Leu298, Leu476, and Met479. Trimming these side chains involves mutating the selected residues to Alanine, performing the docking calculation/simulation, and then restoring the original structures before performing a post-docking minimization. The desired ligands were selected in the workspace and the job was started.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R15GM118304 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained at the Old Dominion University COSMIC facility. The authors acknowledge Dr. Terry-Elinor Reid (Concordia University-Wisconsin) for advice in the use of Glide Induced Fit Docking.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at . . .

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Chhibber A; Woody SK; Rumi MAK; Soares JJ; Zhao L. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 82, 107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma HR; Thakur MK Physiol. Behav. 2015, 145, 71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian Z; Fan J; Zhao Y; Bi S; Si L; Liu Q. Neural Regen. Res 2013, 8, 420–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Levin ER Mol. Endocrinol 2005, 19, 1951–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brzozowski AM; Pike ACW; Dauter Z; Hubbard RE; Bonn T; Engstrom O; Ohman L; Greene GL; Gustafsson JA; Carlquist M. Nature, 1997, 389, 753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Meyers MJ; Sun J; Carlson KE; Marriner GA; Katzenellenbogen BS; Katzenellenbogen JAJ Med. Chem 2001, 44, 4230–4251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Waibel M; De Angelis M; Stossi F; Kieser JJ; Carlson KE; Katzenellenbogen BS; Katzenellenbogen JA Eur. J. Med. Chem 2009, 44, 3412–3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Carroll VM; Jeyakumar M; Carlson KE; Katzenellenbogen JA J. Med. Chem 2012, 55, 528–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manas ES; Unwalla RJ; Xu ZB; Malamas MS; Miller CP; Harris HA; Hsiao C; Akopian T; Hum WT; Malakian K; Wolfrom S; Bapat A; Bhat RA; Stah ML; Somers WS; Alvarez JC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 15106–15119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Curran MP; Wagstaff AJ Drugs 2004., 64, 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perez-Campos EF Drugs 2010, 70, 681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Holub JM; Garabedian MJ; Kirshenbaum K. Molecular QSAR Comb. Sci 2007, 26, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar]; (b) Holub JM; Garabedian MJ; Kirshenbaum K. Molecular BioSystems 2011, 7, 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gryder BE; Rood MK; Johnson KA; Patil V; Raftery ED; Yao LD; Rice M; Azizi B; Doyle DF; Oyelere AK J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 5782–5796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chauhan K; Arun A; Singh S; Manohar M; Chuttani K; Konwar R; Dwivedi A; Soni R; Singh AK; Mishra AK; Datta A. Bioconj. Chem 2016, 27, 961–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Osati S; Ali H; Marques F; Paquette M; Beaudoin S; Guerin B; Leyton JV; van Lier JE Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 27, 443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Jurasek M; Dzubak P; Rimpelova S; Sedlak D; Konecny P; Frydrych I; Gurska S; Hajduch M; Bogdanova K; Kolar M; Muller T; Kmonickova E; Ruml T; Harmatha J; Drasar PB Steroids 2017, 117, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Solum EJ; Vik A; Hansen TV Steroids 2014, 87, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) McCullough C; Neumann TS; Gone JR; He Z; Herrild C; Wondergem J; Pandey RK; Donaldson WA; Sem DS Bioorg. Med. Chem 2014, 22, 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hanson AM; Perera KLIS; Kim J; Pandey RK; Sweeney N; Lu X; Imhoff A; Mackinnon AC; Wargolet AJ; Van Hart RM; Frick KM; Donaldson WA; Sem DS. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 4720–4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Perera KLIS; Hanson AM; Lindeman S; Imhoff A; Lu X; Sem DS Donaldson WA. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 157, 971–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Rostovtsev VV; Green LG; Fokin VV; Sharpless KB Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 2596–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hein JE; Krasnova LB; Iwasaki M; Fokin VV Org. Syn 2011, 88, 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman AK; Colasson B; Fokin VV Org. Lett 2004, 6, 3897–3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso F; Moglie Y; Radivoy G; Yus M. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2010, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creary X; Anderson A; Brophy C; Funk ZJ Org. Chem 2012, 77, 8756–8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guy A; Doussot J; Guette JP; Garreau R; Lemaire M. Synlett 1992, 821–822. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming FF; Wei GJ Org. Chem 2009, 74, 3551–3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabbard RB; Segaloff A. Steroids 1983, 41, 791–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldridge MD; Murray CW; Auton TR; Paolini GV; Mee RP J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des, 1997, 11, 425–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones G; Willett P; Glen RC; Leach AR; Taylor RJ Mol. Biol, 1997, 267, 727–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman BH; Richardson TI; Dodge JA; Pfeifer LA; Durst GL; Wang Y; Durbin JD; Krishnan V; Dinn SR; Liu S; Reilly JE; Ryter KT Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2007, 17, 5082–5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miteva MA; Lee WH ; Montes MO; Villoutreix BO J. Med. Chem 2005, 48, 6012–6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.