Abstract

In this article, the multimaterial extrusion (M-MEX) technology is used to fabricate, in a single step, a three-dimensional printed soft electromagnetic (EM) actuator, based on internal channels, filled with soft liquid metal (Galinstan) and equipped with an embedded strain gauge, for the first time. At the state of the art, M-MEX techniques result underexploited for the manufacture of soft EM actuators: only traditional manufacturing approaches are used, resulting in many assembly steps. The main features of this work are as follows: (1) one shot fabrication, (2) smart structure equipped with sensor unit, and (3) scalability. The actuator was tested in conjunction with a commercial magnet, showing a bending angle of 22.4° (when activated at 4A), a relative error of 0.7%, and a very high sensor sensitivity of 49.7  Two more examples, showing all the potentialities of the proposed approach, are presented: a jumping frog-inspired soft robot and a dual independent two-finger actuator. This article aims to push the role of extrusion-based additive manufacturing for the fabrication of EM soft robots: several advantages such as portability, no cooling systems, fast responses, and noise reduction can be achieved by exploiting the proposed actuation system compared to the traditional and widespread actuation mechanisms (shape memory polymers, shape memory alloys, pneumatic actuation, and cable-driven actuation).

Two more examples, showing all the potentialities of the proposed approach, are presented: a jumping frog-inspired soft robot and a dual independent two-finger actuator. This article aims to push the role of extrusion-based additive manufacturing for the fabrication of EM soft robots: several advantages such as portability, no cooling systems, fast responses, and noise reduction can be achieved by exploiting the proposed actuation system compared to the traditional and widespread actuation mechanisms (shape memory polymers, shape memory alloys, pneumatic actuation, and cable-driven actuation).

Keywords: soft actuator, additive manufacturing, electromagnetic soft actuator, embedded sensor, material extrusion, Galinstan

Introduction

In recent years, additive manufacturing (AM) technologies have been largely exploited for the fabrication of soft structures1,2: several advantages such as reduction in assembly tasks, cost, and time can be achieved. From an actuation standpoint, three-dimensional (3D) printed soft structures mostly based on pneumatic actuation,3,4 shape memory polymers (SMPs),5 shape memory alloys (SMAs),6 cable-driven actuation,7 or a combination of them have been studied.8 Another actuation method that can bring several advantages to the soft robotic domain is the electromagnetic (EM) actuation system.

Generally, the actuators are made up of conductive coils (i.e., copper, gallium): when activated by means of electrical current, the Lorentz force makes the whole actuator move, thanks to the magnetic field generated by a permanent magnet placed near the actuator. Several advantages can be achieved by using EM actuators, compared to their counterparts such as: (1) portability (only batteries need to be involved), (2) noise reduction (making them really appealing for wearable application), (3) fast response (SMPs require some minutes), and (4) no need of cooling systems (SMAs and SMPs require cooling systems to speed up the actuation cycle).

Several examples of soft EM devices can be found in scientific literature: Do et al,9 fabricated small-scale EM actuators made up of silicone, eutectic gallium indium droplets, and magnetic powders obtaining a displacement of 1 mm and a bending angle of 38°. The proposed device can be employed in the soft robotic field for the fabrication of walking robots or small-scale grippers.

Kohls et al10 developed a bio-inspired EM actuator mimicking Xenia soft coral: the EM soft robot is capable of soft compliant motions because of its architecture: it is based on silicone structures with embedded magnets, which can be attracted or repulsed by a magnetic field generated, thanks to soft gallium coils.

Mao et al11 created a silicone EM actuator equipped with channels filled with gallium to obtain several motions: in particular, they showed that this approach can be successfully exploited for the fabrication of swimming robots, flower-inspired robots, and bending structures (a bending of 76° was achieved at 3A).

AM technologies can be employed for the fabrication of EM actuators resulting in several advantages,12 in particular, Material Extrusion (MEX) technology, well known for being the most inexpensive approach, seems to be very promising and appealing.

At the state of the art, three different ways to exploit MEX technologies for the fabrication of EM actuators can be outlined. The first one, called fiber encapsulation consists of the integration of long fibers (copper wires) during the extrusion of thermoplastic materials13–15: recent progress in this technique16–18 could lay the foundation for a huge exploitation of the following approach.

The second method consists of the direct extrusion of a magnetic thermoplastic filament through a calibrated nozzle19: Cao et al20 doped a soft thermoplastic material (shore hardness of 70A) with magnetic particles (50% wt) to create a magnetic filament having a diameter of 1.8 mm processable by commercial fused deposition modelling setups. Several bio-inspired structures were additively manufactured (gripper, butterfly, and flower) and tested in conjunction with a commercial magnet.

The last method found in scientific literature to exploit MEX technologies for the fabrication of EM actuators consists of the extrusion of conductive inks.21 The direct ink writing technology is used, and the conductive inks are extruded through a calibrated nozzle over a flexible substrate (i.e., silicone) to create coils that will be activated by means of electrical current to exploit the Lorentz force.

MEX technologies have become really popular for the possibility to create smart structures: the fabrication of sensor units into objects is really appealing for several reasons such as (1) reduction of manufacturing costs, (2) reduction of assembly tasks, and (3) possibility to obtain feedback from objects.

Several examples of smart objects manufactured using multimaterial MEX technologies can be found in scientific literature: load cell with embedded strain gauges,22 multiaxial force sensor,23 universal jamming gripper with embedded capacitive sensor,24 3D printed accelerometer,25 and pressure sensor for prosthetic applications.26

In this article, a new manufacturing approach based on multimaterial extrusion (M-MEX) technology is presented: a soft EM actuator equipped with internal channels filled with soft metal liquid (Galinstan), and an embedded strain gauge sensor has been fabricated in a one-shot manufacturing cycle. In this way, full advantages from M-MEX technologies have been taken: a smart soft structure providing real-time feedback is obtained. In this research, AM is used for an underexploited field (EM actuators), proving the suitability of EM actuators in the soft robotic domain.

Materials and Methods

The main idea underlying the following research is the one-shot fabrication of a soft EM actuator based on internal channels (filled with Galinstan) and equipped with embedded sensors by using M-MEX technology.

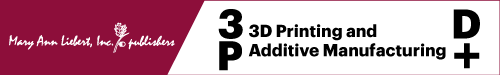

The soft EM actuator, shown in Figure 1a–c is composed of the following parts: (1) a main flexible body, (2) a flexible joint to improve the bending performance, (3) a bottom strain gauge to obtain real-time feedback, and (4) a total of 9 internal channels. In particular, the latter element is crucial to exploit the Lorentz force. The channels have a square profile in accordance to Mao et al11 and they have been filled up with liquid soft Galinstan (a liquid alloy composed of 68% wt. gallium, 22% indium and 10% wt. tin), well known for its good electrical performances. After the Galinstan injection, two metal pins have been assembled over the 3D printed connection to hook up the electrical wires. The Galinstan has been purchased by Peguys, Israel.

FIG. 1.

Soft EM actuator: (a) CAD model; (b) internal channels; (c) Bottom view: embedded strain gauge sensor (white = TPU, black = CPLA); (d) 3D printed EM soft actuator with embedded sensor and channels filled up with Galinstan; and (e) schematic diagram depicting the basic multimaterial-extrusion working mechanism of Ultimaker 3. 3D, three dimensional; CAD, computer-aided design; CPLA, conductive polylactic acid; EM, electromagnetic; TPU, thermoplastic polyurethane.

The M-MEX machine Ultimaker 3 (Ultimaker, The Netherlands) in conjunction with two thermoplastic materials has been used. A soft thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) with a shore harness of 85A and Young's Modulus of 20 MPa has been employed for the flexible parts (main body, joint, and connections for the metal pins), while a conductive polylactic acid (CPLA) with a resistivity of 15 Ω·cm along the layers and 20 Ω·cm perpendicular to the layers has been employed for the sensor fabrication.

The TPU (commercial name “TPU 80A LF”) and CPLA (commercial name “AlfaOhm”) materials have been purchased, respectively, by BASF SE, Germany, and FiloAlfa, Italy.

The overall actuator dimensions along x-, y-, and z-axis are , while the strain gauge results in 6 tracks and a thickness of 0.4 mm.

The main process parameters set during the manufacturing process are listed in Table 1. Moreover, printing speed and infill percentage have been found to be crucial variables for the channel fabrication. If the channels are not properly fabricated, a Gallistan leakage could occur, involving problems during the soft device actuation (impossibility to be activated). Using a trial-and-error approach, a printing speed of 25 mm/s and an infill percentage of 100% were found to ensure a solid channel structure, avoiding Gallinstan leakage. An overview on the fabrication of leakage-free channels exploiting MEX technology can be found in Zeraatkar et al,27 Pavone et al,28 and Zeraatkar et al.29

Table 1.

Printing Parameters

| Process parameter | TPU | CPLA |

|---|---|---|

| Nozzle size (mm) | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Layer thickness (mm) | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Extrusion temperature (°C) | 240 | 260 |

| Printing speed (mm/s) | 25 | 20 |

| Infill percentage (%) | 100 (for the channels) 100 (for the joint) 25 (for other parts) |

100 |

CPLA, conductive polylactic acid; TPU, thermoplastic polyurethane.

In particular, the relationship among strain gauge-extruded single-layer thickness (lt) and total number of layers (tl) has been considered.

As shown in Stano et al,30 the reduction of tl implies a reduction of the final strain gauge resistance and standard deviation: in this way, electrical power losses will be minimized.

Being the overall strain gauge thickness fixed to 0.4 mm, the only way to reduce tl is increasing the single extruded layer thickness (lt) in the slicing software, as shown in Equation (1).

| (1) |

A value of lt equal to 0.2 mm was set; it means that the whole strain gauge is composed of 2 consecutive layers to minimize the welding effect (number of voids between adjacent extruded layers) found in Stano et al.30 Moreover, further characterizations about the CPLA viscoelastic behavior will be carried out to improve the dimensional accuracy of 3D printed sensors.

The strain gauge geometry proposed in Stano et al22 was used throughout this work; however, recent works pave the way to sinusoidal and wave-based profiles for soft stretchable strain sensors.31,32

The total printing time and cost are, respectively, 97 min and 3.75€.

The main advantages of the proposed manufacturing approach, compared to the main works using MEX technique, to exploit the EM actuation system found in scientific literature and discussed in the introductions are as follows:

-

1.

The EM actuation is achieved by employing a soft metal liquid metal instead of rigid copper wires: in this way, soft devices can be fabricated without recurring to rigid external elements.13,14

-

2.

The EM actuation is achieved by employing a soft metal liquid metal instead of extruding thermoplastic composite materials loaded with magnetic fillers.19,20 The main issue related to magnetic thermoplastic materials is their low processability: the magnetic fillers make the whole filament brittle and difficult to be extruded, generally problems like nozzle clogging and breakage of filaments between the 3D printers pushing gears occur. Using the proposed manufacturing approach, all the problems described above have been overcome.

The proposed 3D printed soft EM actuator filled with soft liquid Gallinstan is shown in Figure 1d. The working mechanism of the used M-MEX machine (Ultimaker 3) is shown in Figure 1e.

EM Actuator Characterization

The proposed 3D printed soft EM actuator was characterized to evaluate (1) bending performance as a function of the applied current and (2) the embedded strain gauge performance. A permanent magnet (purchased by Supermagnete.de, Germany) was used to generate a magnetic field of 1.29T.

In accordance to Mao et al,11 the equilibrium Lorentz force equation shown in Equation (2) is as follows:

| (2) |

where is the distance between the permanent magnet and the channels, i is the number of the channel (), and M  is the total magnetic moment as shown in Equation (3)

is the total magnetic moment as shown in Equation (3)

where B is the magnetic field, I is the input current , and L is the length of the main channels.

Three different current inputs (2A, 3A, and 4A) were tested, evaluating the final EM soft actuator bending angle: 10 cycles for every current input were performed.

It is worth mentioning that when a current input of 1A was provided, the bending motion of the proposed soft EM actuator is neglectable.

The testing protocol is as follows: the current is provided to the Galinstan channel for 1 s (because of the Lorentz force, the EM soft actuator results in bending motion); after the current is set to 0A for 1 s (rest time) and the actuator get backs to its initial position, the current is provided again for 1 s, the whole cycle is repeated 10 times.

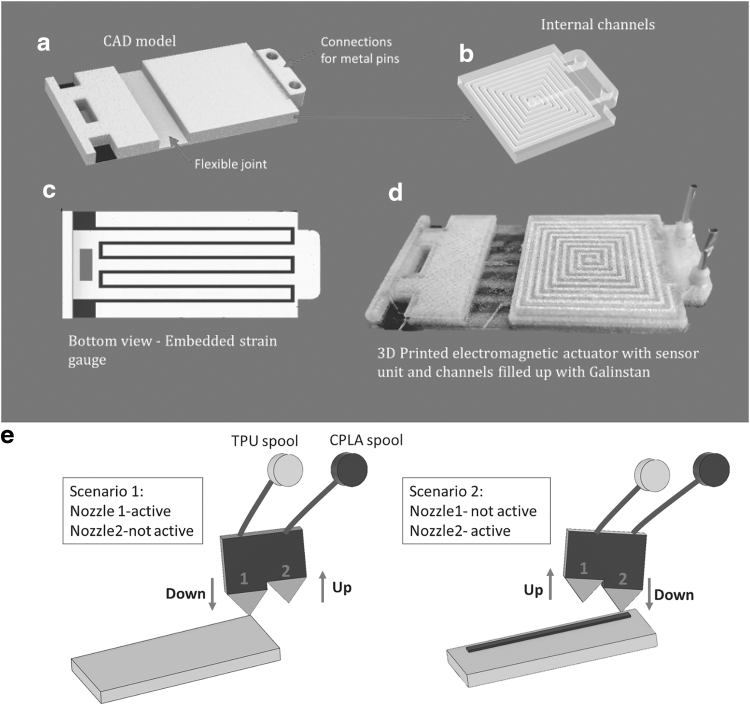

The current input providing the best bending performance is 4A (Fig. 2a): a bending angle of 22.4° is obtained, resulting in, respectively, 35.4% and 46.9% higher than the bending angle obtained at 3A and 2A. The standard deviation has been calculated on 10 cycles, resulting really low for every current input (standard deviation of 0.21° at 2A, standard deviation of 0.16° at 3A, and standard deviation of 0.17° at 4A) (Fig. 2b, c).

FIG. 2.

Characterization of the EM soft actuator. (a) Working principle of the soft EM actuator with current input of 4A. (b) Observed bending angle as a function of the current inputs. (c) Comparison of the bending angle at the current input variation versus number of cycle. (d) Embedded sensor behavior: resistance variation at 4A current input.

When a current input of 4A is provided, a relative error (e), a good metric to evaluate the accuracy in terms of bending of the proposed actuator, was found to be 0.7%. The low relative error makes the proposed EM soft device appealing for applications requiring high accuracy, such as biomedical and industrial devices.

The strain gauge performance has been analyzed: the best current input, namely 4A, has been provided to the EM actuator for a total of 100 consecutive cycles. The current is provided for 1 s, followed by an off period of 5 s, for a total of 100 times. Two electrical wires have been welded to the strain gauge pads and connected to the benchtop multimeter (GW Instek, GDM-8341), which in turn was connected to the laptop to collect data.

From the testing phase, it stands out that the strain gauge change of resistance is characterized by two phases: an initial phase in which the change in resistance tends to grow and a second phase where it is stable (Fig. 2d). The authors explain the two different phases as follows: during the first phase, the overall change in resistance constantly grows for the first 28 cycles because of the (1) Mullin effect and (2) material (TPU) hysteresis.

After the 28th cycle, a stabilization in the material hysteresis and mitigation of the Mullins effect occur and the change in resistance of the embedded strain gauge result stable. In particular, the sensitivity (s) of the strain gauge throughout the second phase (stability phase) is 49.7  and R2 is equal to 0.96. In particular, the high sensitivity allows the exploitation of the proposed EM actuator without recurring to any resistance amplifier. The following results suggest that the proposed 3D printed soft EM actuators need to be trained for 28 cycles before the usage, to obtain consistency in the bending behavior.

and R2 is equal to 0.96. In particular, the high sensitivity allows the exploitation of the proposed EM actuator without recurring to any resistance amplifier. The following results suggest that the proposed 3D printed soft EM actuators need to be trained for 28 cycles before the usage, to obtain consistency in the bending behavior.

It is worth mentioning that the training phase (28 cycle) mostly depends on two factors: (1) size of the device (changing the size, the amount of training cycles can change) and (2) material properties: every material (even different kinds of TPU) is characterized by different viscoelastic properties, affecting the bending behavior of the EM soft device. Every soft EM device fabricated with the proposed approach needs to be initially tested to understand when the stabilization phase (in terms of consistency in the bending behavior) occurs. Further work will focus on the fatigue analysis of the proposed soft EM device, paying particular attention at the interface adhesion among CPLA and TPU when the device is subject to repetitive cycles.

The embedded strain gauge has been used to obtain real-time feedback; in the future, it can be used to create closed control loops, improving the automation degree of the proposed EM soft actuator.

Applications: Bio-Inspired Frog Robot and Independent Dual Actuator

To prove the potentialities of the proposed manufacturing approach, two different applications have been developed: a jumping bio-inspired soft frog (Fig. 3a) and an independent dual actuator (IDA) (Fig. 4a, b).

FIG. 3.

Bio-inspired EM soft Frog: (a) CAD of the soft Frog; (b) Rest position (at 0A); (c) characterization of jumping motion at four different frog orientation: North, South, Right, Left direction.

FIG. 4.

Independent Dual soft EM Actuator (IDA) and characterization: (a) CAD of the proposed IDA; (b) Bottom view of the embedded strain gauge sensors; (c) zero-current input for fingers 1 and 2; (d) 4A current input provided to both the fingers: bending of both the fingers; (e) bending of finger 1: 4A current input provided to finger 1 and 0A current input provided to finger 2; (f) bending of finger 2: 4A current input provided to finger 2 and 0A current input provided to finger 1. IDA, independent dual actuator.

The bio-inspired jumping soft frog was used to demonstrate that the proposed EM soft device can be employed for soft robotics applications: nowadays, a challenging topic concerns the fabrication of animal-based soft robots capable of crawl, jump, and swim.33–35

The frog-inspired soft EM robot is based on a core main body equipped with internal channels filled with Galinstan (the same of the EM soft actuator shown in EM Actuator Characterization section) and four legs (one for each corner of the main body) designed with flexible TPU joints to improve jumping motions. TPU was used to manufacture the soft frog, setting the same printing parameters listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Jumping Movement Evaluation

| Orientation | Mean position |

Standard deviation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x (mm) | y (mm) | x (mm) | y (mm) | |

| North | ||||

| Leg 1 | −23.15 | 80.51 | 4.61 | 1.34 |

| Leg 2 | 52.36 | 68.17 | 4.34 | 5.91 |

| Leg 3 | 42.49 | 5.35 | 3.24 | 5.64 |

| Leg 4 | −43.25 | 7.58 | 2.71 | 1.90 |

| South | ||||

| Leg 1 | −99.73 | −35.49 | 2.39 | 11.70 |

| Leg 2 | −57.24 | 39.02 | 6.80 | 7.79 |

| Leg 3 | 26.21 | 0.470 | 2.56 | 6.03 |

| Leg 4 | −23.86 | −78.45 | 7.42 | 4.58 |

| East | ||||

| Leg 1 | −15.47 | 37.84 | 3.01 | 1.08 |

| Leg 2 | 22.56 | −0.58 | 2.29 | 2.29 |

| Leg 3 | 0.14 | −8.05 | 1.43 | 7.13 |

| Leg 4 | 49.89 | −75.22 | 5.83 | 4.53 |

| West | ||||

| Leg 1 | −104.02 | 34.56 | 1.39 | 3.23 |

| Leg 2 | −23.51 | 64.64 | 3.38 | 9.27 |

| Leg 3 | 8.64 | −16.98 | 2.74 | 10.87 |

| Leg 4 | −76.22 | −46.96 | 4.54 | 5.28 |

The jumping performance of the soft EM frog has been evaluated, in terms of position in the x- and y-space and repeatability.

The soft EM frog body was placed parallel to the permanent magnet on the horizontal plane: the center of the magnet is fixed as the zero of the axis system for each orientation. Four different orientations were tested: North, South, Right, and Left.

The following testing protocol was used: for each orientation, one by one, a single input current of 4A (the current input providing the best result in EM Actuator Characterization section) is provided to the Galinstan channel, and the soft EM frog results in jumping movement. Subsequently, the current is set to 0A for 10 s and the frog soft robot is placed at and . The whole cycle is repeated three times for each orientation.

A virtual marker for each leg was used to evaluate the x- and y-position (Fig. 3b) of the soft frog: the jumping movement is substantially repeatable, and in Table 2, the standard deviation of each leg (1–4), for every orientation (North, South, Right, and Left), is listed. The standard deviation has a random behavior: for the x-position, the standard deviation ranges from 1 to 5 mm, and for y-position, it ranges from 1 to 10 mm. The mean (x- and y-position) standard deviation for North; South; Right; and Left orientation is, respectively, (3.72; 3.69) mm, (4.79; 7.53) mm, (3.14; 3.76) mm, and (3.01; 7.16) mm, as shown in Figure 3c. The following outcomes indicate that the presented EM bio-inspired soft robot can be employed as jumping robot; moreover, future works will focus on the modeling, simulation, and control aspects of the jump motion.

A great advantage offered by M-MEX technique and in general by AM methods concerns the possibility to fabricate assembly-free device that can be scaled up and down.36

To demonstrate that the proposed fabrication method is suitable for small size, nonassembly EM soft actuator, an IDA was designed and fabricated. The EM-based IDA takes inspiration from human fingers: they are connected to the hand, and they can be activated both independently and simultaneously. The proposed IDA device is composed of two TPU fingers connected to each other at the base: each finger is 50 mm long and 23 mm wide and composed of nine internal channels (which will be filled up with Galinstan after the fabrication step) and one bottom strain gauge sensor. The distance between the two fingers is 4 mm.

The possibility to selectively choose which finger will be activated is really appealing and can find applications in many fields such as (1) on-off switching devices for button without human intervention and (2) swimming robot (mimicking fish fins).

Another important aspect of the proposed IDA is related to the presence of two different strain gauges (one for each finger), which provide feedbacks (change in resistance) when the fingers are activated.

The IDA device was characterized to evaluate (1) bending performance and (2) the embedded strain gauge performance: only a 4A input current was used for the tests.

The current input has been provided (from a rest zero-position, with 0A for finger 1 and finger 2, as shown in Fig. 4c) for a total of 10 cycles (single cycle: current on for 1 s and off for 1 s) in three different configurations: (1) only the finger 1 has been activated (Fig. 4e, f), (2) only the finger 2 has been activated (Fig. 4d), and (2) both the fingers 1 and 2 have been simultaneously activated.

A mean bending angle of 15.5° (standard deviation of 0.4°) and 15.4° (standard deviation of 0.6) were found when only the finger 1 and the finger 2 were separately actuated.

As shown in Figure 5a, the strain gauge sensitivity of the finger 1 when activated (finger 2 not activated) is

(), while the strain gauge sensitivity of finger 2 (Fig. 5b) when activated (finger 1 not activated) is

(), while the strain gauge sensitivity of finger 2 (Fig. 5b) when activated (finger 1 not activated) is

().

().

FIG. 5.

Strain gauge sensitivity: (a) resistance variation (strain gauge sensitivity) of finger 1 when activated (finger 2 not activated); (b) resistance variation of finger 2 when activated (finger 1 not activated).

The whole IDA device has been fabricated in a single step cycle resulting, respectively, in a manufacturing time and cost of 72 min and 3.06€: it consists of two strain gauges (CPLA material) and two soft (TPU material) bodies.

Full advantages have been taken from the M-MEX approach: a comparison is here provided with the same IDA device fabricated in a modular way (two separate soft bodies, two separate strain gauges, and a connection structure). In this case, the 3D printing cost is 4.57€ (1.68€ for every soft body, 0.54€ for every strain gauge, and 0.13€ for the connection structure), and the manufacturing time is 140 min (48 min for every soft body, 27 min for every strain gauge, and 7 min for the connection structure). On top of that, four manual assembly tasks are required: assembly of the two soft bodies with the connection part (2 tasks), and assembly of the two strain gauges in the bottom part of each soft body (2 tasks).

The authors assumed a total manual assembly time of 30 min for a total manufacturing cost and time of 4.57€ and 150 min. It is important to point out that the human operator cost/minute has not been considered.

The exploitation of the M-MEX approach, in this specific case, lead to a reduction in cost and time, respectively, of 14.65% and 55.2%, proving all the potentialities of the proposed 3D printing method.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates the advantages offered by the M-MEX AM process for the fabrication of soft EM actuators: even though this class of actuator is really appealing for soft robotic applications, it results, at the state of the art, still underexploited.

The main benefit of the proposed manufacturing approach consists in the monolithic fabrication of the soft EM device equipped with (1) internal channels (filled up with liquid metal Galinstan) and (2) an embedded strain gauge sensor. As a matter of fact, manufacturing steps and assembly tasks have been abruptly reduced, making M-MEX technology suitable for the fabrication of the proposed soft EM devices.

A soft EM actuator used for bending purpose has been characterized showing a bending angle of 22.4° and a very low relative error of 0.7%, while the 3D printed embedded strain gauge sensitivity was found to be 49.7  Two more examples have been presented: a soft frog-inspired EM robot and a dual finger independent actuator (IDA) equipped with two separate strain sensors. The latter, can be used for industrial application such as EM switcher. It was also proved that the usage of the M-MEX approach for the fabrication of the dual independent actuator (IDA) with embedded sensors resulted in a reduction of 14.65% and 55.2% in manufacturing time and cost, compared to a modular MEX approach. In conclusion, the outcomes of this research lay the foundation for a huge exploitation of M-MEX technology (and AM technologies, in general) for the fabrication of EM devices equipped with sensors.

Two more examples have been presented: a soft frog-inspired EM robot and a dual finger independent actuator (IDA) equipped with two separate strain sensors. The latter, can be used for industrial application such as EM switcher. It was also proved that the usage of the M-MEX approach for the fabrication of the dual independent actuator (IDA) with embedded sensors resulted in a reduction of 14.65% and 55.2% in manufacturing time and cost, compared to a modular MEX approach. In conclusion, the outcomes of this research lay the foundation for a huge exploitation of M-MEX technology (and AM technologies, in general) for the fabrication of EM devices equipped with sensors.

Authors' Contributions

A.P., G.S., and G.P.: conceptualization, methodologies, and writing-original draft. G.P.: supervision and writing-review and editing.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

No funding have been used for this article.

Supplementary Movies

-

1.

Soft EM actuator based on internal channels (filled with Galinstan) and equipped with embedded sensors: https://youtu.be/EhHJgAKvlJc

-

2.

Applications (Soft jumping Frog and Independent Dual Actuator): https://youtu.be/6_164MAnaik

References

- 1. Stano G, Percoco G. Additive manufacturing aimed to soft robots fabrication: A review. Extrem Mech Lett [Internet] 2021;42:101079; doi: 10.1016/j.eml.2020.101079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walker S, Yirmibeşoğlu OD, Daalkhaijav U, et al. Additive manufacturing of soft robots. Robot Syst Auton Platforms 2019;2019:335–359. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tawk C, Alici G. A review of 3D-printable soft pneumatic actuators and sensors: Research challenges and opportunities. Adv Intell Syst 2021;3(6):2000223. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zolfagharian A, Mahmud MAP, Gharaie S, et al. 3D/4D-printed bending-type soft pneumatic actuators: Fabrication, modelling, and control. Virtual Phys Prototyp [Internet] 2020;15(4):373–402; doi: 10.1080/17452759.2020.1795209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen T, Shea K. An autonomous programmable actuator and shape reconfigurable structures using bistability and shape memory polymers. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2018;5(2):91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodkhe S, Vigo L, Zhu S, et al. 3D printing to integrate actuators into composites. Addit Manuf [Internet] 2020;35(January):101290; doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2020.101290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khondoker MAH, Baheri N, Sameoto D. Tendon-driven functionally gradient soft robotic gripper 3D printed with intermixed extrudate of hard and soft thermoplastics. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2019;6(4):191–203. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang W, Ahn SH. Shape memory alloy-based soft gripper with variable stiffness for compliant and effective grasping. Soft Robot 2017;4(4):379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Do TN, Phan H, Nguyen TQ, et al. Miniature soft electromagnetic actuators for robotic applications. Adv Funct Mater 2018;28(18):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kohls N, Dias B, Mensah Y, et al. Compliant electromagnetic actuator architecture for soft robotics. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA): IEEE; 2020; pp. 9042–9049. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mao G, Drack M, Karami-Mosammam M, et al. Soft electromagnetic actuators. Sci Adv 2020;6(26):eabc0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tiismus H, Kallaste A, Vaimann T, et al. State of the art of additively manufactured electromagnetic materials for topology optimized electrical machines. Addit Manuf 2022;55(March):102778. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saari M, Cox B, Richer E, et al. Fiber encapsulation additive manufacturing: An enabling technology for 3D printing of electromechanical devices and robotic components. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2015;2(1):32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim C, Sullivan C, Hillstrom A, et al. Intermittent embedding of wire into 3D prints for wireless power transfer. Int J Precis Eng Manuf [Internet] 2021;22(5):919–931; doi: 10.1007/s12541-021-00508-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saari M, Xia B, Cox B, et al. Fabrication and analysis of a composite 3D printed capacitive force sensor. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2016;3(3):137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamidi A, Tadesse Y. Single step 3D printing of bioinspired structures via metal reinforced thermoplastic and highly stretchable elastomer. Compos Struct [Internet] 2019;210:250–261; doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.11.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Z, Smith DE. Finite element modelling of fully-coupled flow/fiber-orientation effects in polymer composite deposition additive manufacturing nozzle-extrudate flow. Compos Part B Eng [Internet] 2021;219:108811; doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.108811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Z, Smith DE, Jack DA. A statistical homogenization approach for incorporating fiber aspect ratio distribution in large area polymer composite deposition additive manufacturing property predictions. Addit Manuf [Internet] 2021;43:102006; doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2021.102006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taylor AP, Velez Cuervo C, Arnold DP, et al. Fully 3D-printed, monolithic, mini magnetic actuators for low-cost, compact systems. J Microelectromechanical Syst 2019;28(3):481–493. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cao X, Xuan S, Sun S, et al. 3D printing magnetic actuators for biomimetic applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021;13(25):30127–30136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yan C, Zhang X, Ji Z, et al. 3D-printed electromagnetic actuator for bionic swimming robot. J Mater Eng Perform [Internet] 2021;30(9):6579–6587; doi: 10.1007/s11665-021-05918-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stano G, Di Nisio A, Lanzolla A, et al. Additive manufacturing and characterization of a load cell with embedded strain gauges. Precis Eng [Internet] 2020;62:113–120; doi: 10.1016/j.precisioneng.2019.11.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim K, Park J, Suh J hoon, et al. 3D printing of multiaxial force sensors using carbon nanotube (CNT)/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) filaments. Sensors Actuators, A Phys [Internet] 2017;263:493–500; doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2017.07.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loh LYW, Gupta U, Wang Y, et al. 3D printed metamaterial capacitive sensing array for universal jamming gripper and human joint wearables. Adv Eng Mater 2021;23(5):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arh M, Slavič J, Boltežar M. Design principles for a single-process 3D-printed accelerometer—Theory and experiment. Mech Syst Signal Process 2021;152:107475. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lathers S, Mousa M, La Belle J. Additive manufacturing fused filament fabrication three-dimensional printed pressure sensor for prosthetics with low elastic modulus and high filler ratio filament composites. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2017;4(1):30–40. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zeraatkar M, De Tullio MD, Percoco G. Fused filament fabrication (FFF) for manufacturing of microfluidic micromixers: An experimental study on the effect of process variables in printed microfluidic micromixers. Micromachines 2021;12(8):858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pavone A, Stano G, Percoco G. On the Fabrication of modular linear electromagnetic actuators with 3D printing technologies. Procedia CIRP [Internet] 2022;110(C):139–144; doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2022.06.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zeraatkar M, de Tullio MD, Pricci A, et al. Exploiting limitations of fused deposition modeling to enhance mixing in 3D printed microfluidic devices. Rapid Prototyp J 2021;27(10):1850–1859. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stano G, Di Nisio A, Lanzolla AM, et al. Fused filament fabrication of commercial conductive filaments: Experimental study on the process parameters aimed at the minimization, repeatability and thermal characterization of electrical resistance. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2020;111:2971–2986. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soomro AM, Khalid MAU, Shah I, et al. Highly stable soft strain sensor based on Gly-KCl filled sinusoidal fluidic channel for wearable and water-proof robotic applications. Smart Mater Struct 2020;29(2):025011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ahmed F, Soomro AM, Ashraf H, et al. Robust ultrasensitive stretchable sensor for wearable and high-end robotics applications. J Mater Sci Mater Electron [Internet] 2022;33:26447–26463; doi: 10.1007/s10854-022-09324-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hamidi A, Almubarak Y, Rupawat YM, et al. Poly-Saora robotic jellyfish: Swimming underwater by twisted and coiled polymer actuators. Smart Mater Struct 2020;29(4):045039. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shintake J, Cacucciolo V, Shea H, et al. Soft biomimetic fish robot made of dielectric elastomer actuators. Soft Robot 2018;5(4):466–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Soomro AM, Memon FH, Lee JW, et al. Fully 3D printed multi-material soft bio-inspired frog for underwater synchronous swimming. Int J Mech Sci [Internet] 2021;210:106725; doi: 10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2021.106725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lussenburg K, Sakes A, Breedveld P. Design of non-assembly mechanisms: A state-of-the-art review. Addit Manuf 2021;39:101846. [Google Scholar]