Abstract

A major challenge to advance lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for RNA therapeutics is the development of formulations that can be produced reliably across the various scales of drug development. Microfluidics can generate LNPs with precisely defined properties, but have been limited by challenges in scaling throughput. To address this challenge, we present a scalable, parallelized microfluidic device (PMD) that incorporates an array of 128 mixing channels that operate simultaneously. The PMD achieves a >100× production rate compared to single microfluidic channels, without sacrificing desirable LNP physical properties and potency typical of microfluidic-generated LNPs. In mice, we show superior delivery of LNPs encapsulating either Factor VII siRNA or luciferase-encoding mRNA generated using a PMD compared to conventional mixing, with a 4-fold increase in hepatic gene silencing and 5-fold increase in luciferase expression, respectively. These results suggest that this PMD can generate scalable and reproducible LNP formulations needed for emerging clinical applications, including RNA therapeutics and vaccines.

Keywords: mRNA, siRNA, lipid nanoparticles, gene therapy

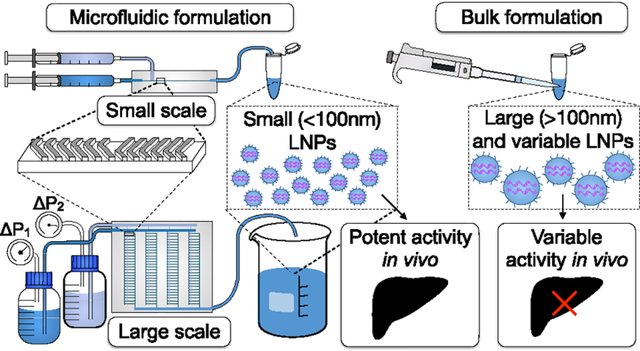

Graphical Abstract

RNA therapeutics, a potent and versatile alternative to pharmacological drugs such as small molecules and proteins, treat illnesses by modifying the expression of disease-related genes that are considered “undruggable” with current medicines.1,2 These disease-related genes can be controlled by various approaches: small interfering RNA (siRNA) or microRNA (miRNA) for gene knockdown, messenger RNA (mRNA) for transient gene expression, or a combination of guide RNA (gRNA) and mRNA for CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing.3–7 Recent advances in RNA therapeutics led to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals’ lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-based siRNA therapeutic Onpattro and their N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) siRNA conjugate Givlaari, in addition to the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech that have received emergency use authorization.8−12 Since naked RNAs are subject to rapid degradation by serum endonucleases and cannot readily cross cell membranes due to charge repulsion, RNA therapeutics require a delivery platform for intracellular delivery.4,13,14 Synthetic delivery vehicles, such as LNPs, have been developed for RNA delivery due to their biocompatibility, potent intracellular delivery, and protection from innate immune recognition and endonuclease degradation.4,15–21 A key challenge toward the broad clinical translation of LNP RNA therapeutics are formulation techniques that can robustly and consistently produce formulations on production scales that range from early phases of development to clinical applications.

LNPs can be formulated by several methods, where a lipid solution dissolved in ethanol is mixed with a nucleic acid solution to produce LNPs via self-assembly.22,23 In each method, size is an important parameter to control as it greatly influences LNP fate in vivo.24 Bulk processes do not require specialized equipment, but they lack precise control over mixing time and thus create large (>100 nm), polydisperse particles with low encapsulation efficiency that varies batch-to-batch and can require more downstream processing in large-scale manufacturing, which reduces yields and increases production costs.5,25–27 Alternatively, microfluidic mixing processes have been designed to achieve rapid and controlled folding of fluids within microseconds to milliseconds, for precise control of particle size, more homogeneous size distributions, higher encapsulation efficiencies, and greater reproducibility than bulk methods.28,29 An example of this approach is hydrodynamic flow focusing, a microfluidic laminar flow method where particles are formed at the interface of laminar flowstreams; however, this process is limited in throughput (<10 mL/h) and mainly used for preparing liposomes, which have less structural complexity than LNPs.30–33 Another type of rapid mixing process is T-junction mixing, where turbulent mixing in a macroscopic channel (>1 mm)5,20,29,34 can achieve small LNP sizes (<100 nm)35 but cannot scale down to the small volumes (μL) needed for high-throughput library screening of nanomaterials.21,24,29

In this paper, we focus on the staggered herringbone micromixer (SHM) design, a widely applied, low-throughput (<100 mL/h) microfluidic strategy for the production of precisely defined LNPs.26,29,36 This design enables reagents to be rapidly and controllably mixed (<10 ms) with high reproducibility, LNP size homogeneity, and the lowest reported LNP sizes (<30 nm).26,28,29 Despite these notable successes, there remains an unmet need for a single integrated design that can formulate nucleic acid therapeutics in a controlled manner on production scales ranging from benchtop to human applications for LNPs to reach their full clinical potential. Adding additional relevance to this challenge, for LNP-based COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, the formulation of LNPs has been identified as the bottleneck for the production process.37

We address this challenge by developing a parallelized microfluidic device (PMD) that can incorporate an array of SHM mixing channels (1×, 10×, 128×) that operate simultaneously for the formulation of LNPs encapsulating RNA therapeutics, without sacrificing the desirable LNP physical properties and potency typical of microfluidic-generated LNPs. This technology is directly scalable from small-scale discovery experiments (mL/h) to clinically relevant production rates (L/h) by simply integrating more mixing units into a single microfluidic chip, eliminating the need for additional optimization or further scale-up challenges. To address this challenge and to ensure that each device in the array produces LNPs with identical physical parameters, we used a ladder geometry that incorporates flow resistors upstream of each SHM to distribute fluid evenly to each SHM in the array.38,39 Moreover, the flow resistors decoupled the design of the mixing channels and the design requirements for parallelization, allowing for the modular incorporation of mixing channel geometries into our architecture without redesign. While parallelized microfluidic architectures have been implemented for NP production,29,40,41 these have been limited in throughput and cannot be scaled to the thousands of devices necessary for operation at the commercial scale.

Here, we compared three formulation methods, a microfluidic single channel device, PMD, and bulk mixing, to produce LNPs that encapsulate either siRNA for gene knockdown in vitro and in vivo or mRNA for translation in vivo. For these studies, we used a gold standard ionizable lipid with formulations previously optimized for siRNA and mRNA delivery to demonstrate scalable production of LNPs using our microfluidic platform. The fabrication of this PMD addresses the clinical need of scalable LNP production, with the potential to enable rapid formulation of reproducible and homogeneous LNPs for a broad range of RNA therapeutics and vaccines.

FABRICATION OF A SCALABLE, PARALLELIZED MICROFLUIDIC DEVICE

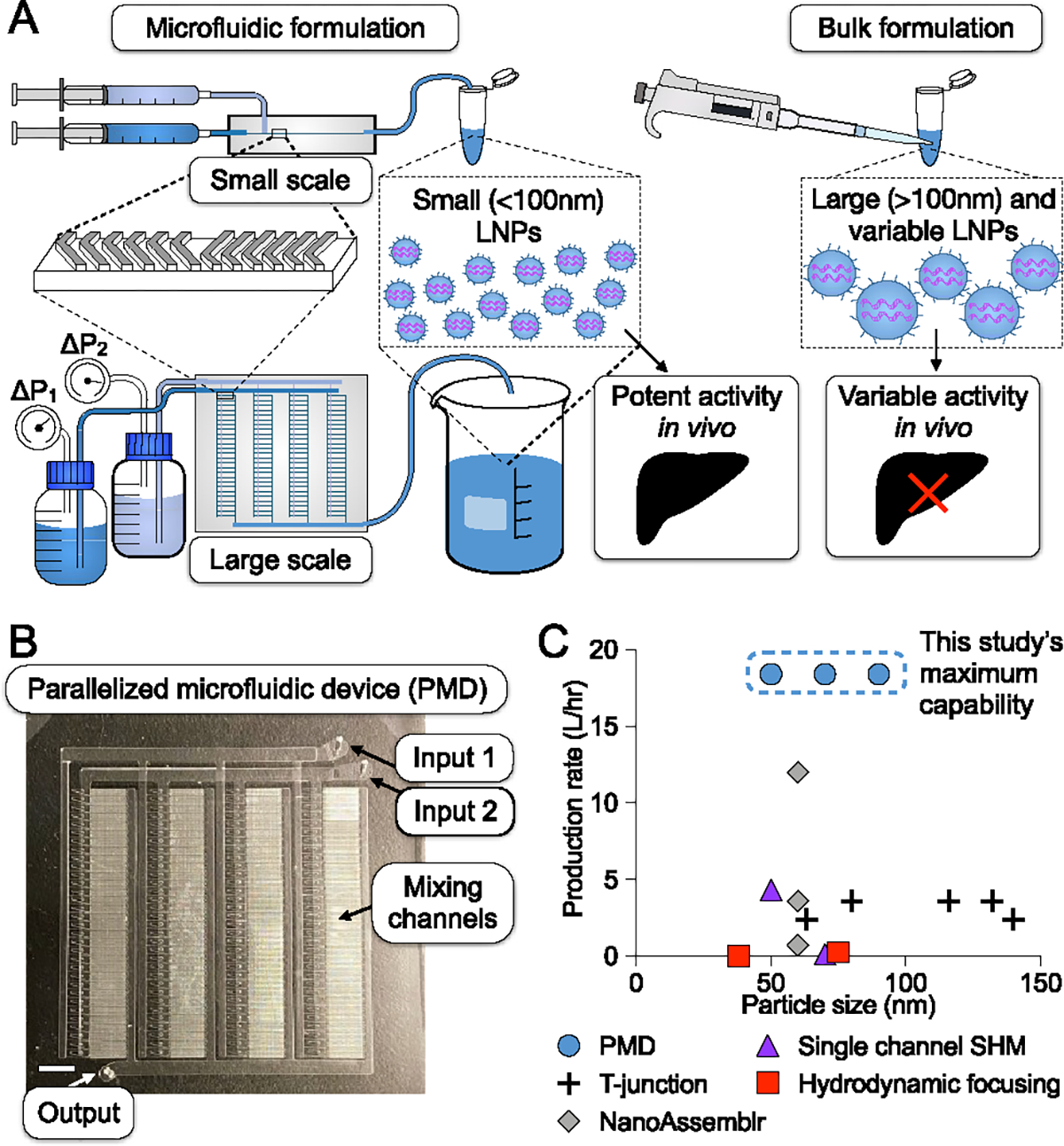

We have fabricated a PMD for large-scale manufacturing of LNPs that increases production rates by over 100-fold (18.4 L/h) compared to the current single channel microfluidic device (Figure 1).26 By incorporating a ladder design architecture, flow resistors, and soft lithography techniques, we patterned our designs into a single piece of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) that can be operated at moderate pressures (50 psi).42 PDMS was selected for the device material due to its low cost, widespread use in the field, and compatibility with the intended solvents.43,44 By incorporating the existing SHM geometry,26,45 we take advantage of the already demonstrated benefits of microfluidic LNP production, such as reproducible production of small size LNPs (<100 nm) and low polydispersity (Figure 1A). Compared to a bulk-mixing method for LNP production, such as repeated pipetting to mix solutions, microfluidic devices produce LNPs with higher potency in vivo (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Fabrication of a scalable PDMS-based microfluidic platform for precise and large-scale RNA lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations. (A) Microfluidic formulation produces smaller and more homogeneous LNPs for potent RNA delivery, while larger and more heterogeneous LNPs produced by bulk methods are more variable in terms of RNA delivery. Microfluidic formulation can be scaled up using the same design (staggered herringbone micromixers) for rapid mixing to produce comparable LNPs for RNA delivery. (B) Photograph of the PDMS device, which incorporates 128 (4 × 32) mixing channels with only two inlets and one outlet. Scale bar: 5 mm. (C) Production rate comparison of different continuous LNP formulation methods (T-junction;7,34,46–48 hydrodynamic focusing;32,33 SHM;26,29 NanoAssemblr Ignite, NxGen Blaze, GMP system49), highlighting the total volumetric production rate and respective LNP size.

Our PMD (Figure 1B) consists of an array of SHMs, each connected to layers of channels that deliver and collect fluid from each device in the array. The PMD is designed to incorporate 1×, 10×, or 128× mixing channels in a ladder architecture to ensure that each device in the array operates with the same flow conditions (Figure 2A). The 128× micromixer device is arranged in an array of 4 rows of 32 SHMs. In our ladder design, supply channels connect to the array using 4 rows of delivery channels, each connected by a single arterial line that connects to the external inlets and outlets. Upstream of each SHM are flow resistors (Figure 2B), and each SHM mixing channel is connected to the second layer of channels (in a plane above the mixing channels) by a vertical via (Figure 2B, G).

Figure 2.

Incorporation of ladder design architecture, flow resistors, and herringbone micromixers out of the parallelized microfluidic device (PMD) enable large-scale LNP production. (A–C) Schematic diagram for the design of this device containing 4 rows of 32 mixing channels (A), highlighting the individual mixing unit design with a top view and a side view (B) and the individual mixing cycle design with a top, angled, and side view (C). Direction of flow is indicated by white arrows. Schematics are not to scale. (D) Circuit model of the delivery channels (Rdelivery), resistors (Rresistor), mixing channels (Rmixing), and individual mixing channel unit (Rdevice). (E) Resistance of an individual mixing channel unit versus length of the mixing channel, where the Rdevice is dominated by the resistance of the fluidic resistors, not the mixing channels. Rdevice is normalized to the resistance of an individual mixing channel unit with resistors and a mixing channel length of 20 cycles. (F) Device features. Scale bar: 200 μm. (G) Cross section of the PMD. Scale bar: 200 μm.

The devices were fabricated in PDMS using double-sided imprinting.42 While fabrication using double-sided imprinting is a robust prototyping method for this design, this approach can also be translated to silicon/glass devices, where device yields of 100% can be achieved in addition to increased solvent compatibility and compliance with industrial regulations (i.e., Good Manufacturing Practice).50 Compared to previously published production rates using other methods of LNP formulation, our PMD can achieve high production rates while maintaining advantageous microfluidic parameters for the formulation of small LNPs (Figure 1C).

MICROFLUIDIC DESIGN PRINCIPLES

To ensure uniform operation of each of the SHMs in the array, the fluidics are designed such that each SHM receives its inputs with the same flow rates. To achieve this goal, we borrowed a design principle developed for designing arrays of droplet microfluidic devices, wherein each mixing unit is designed such that the fluidic resistance of each mixing unit is much greater than that of the delivery channels, allowing the SHMs to operate as if they are connected in parallel.38,39 However, because we developed this technique to be modular such that it can be applied to any nanoparticle-generating device at any level of parallelization, we did not want to have the parallelization considerations place any restrictions on the design of the individual SHMs. To this end, we incorporated flow resistors50,51 upstream of each SHM (Figure 2B, C, F), which dominate the overall resistance of the device, thus decoupling the design of the mixing channels and its requirements for parallelization. The resistance of a single mixing device is the sum of the resistance of flow resistors (Rresistor) and the resistance of SHMs (Rmixing) to make a total device resistance (Rdevice) (Figure 2D), which is dominated by the resistance of the fluidic resistors (Figure 2E). Additionally, this ladder geometry is designed to be resilient to clogging, a key challenge in the field of microfluidics,52 since the SHMs are connected in parallel; thus, if one SHM has a change in fluidic resistance due to clogging, this has a minor impact on the flow distribution to other SHMs. Further, we incorporated lithographically defined in-line filters that are smaller (20 μm) than our smallest channels (35 μm) such that any debris or aggregates that enter the device will be caught upstream by the filters and cannot block the downstream channels.

VALIDATION OF PARALLELIZED MICROFLUIDIC DESIGN

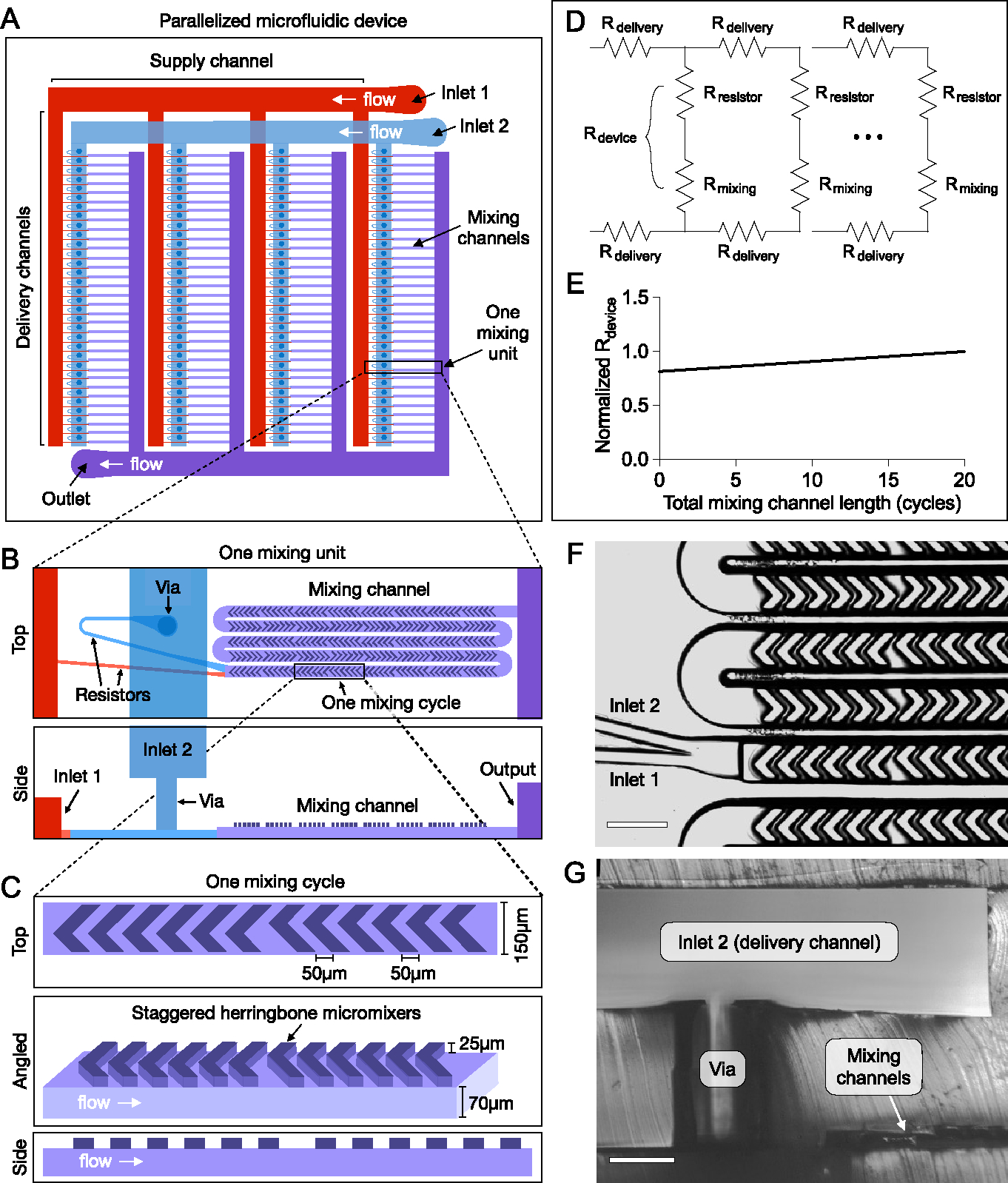

To validate our parallelized microfluidic design, we performed mixing analysis by flowing two different fluorescent dyes through the device and quantifying a mixing value for various flow rates and channel positions. The two dyes, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dextran and rhodamine dextran, were selected since they roughly mimic the size of RNAs53 and because the intensity of each fluorescent stream could be quantified independently by different filters.

We fabricated a single channel device to evaluate mixing efficiency at different flow rates by quantifying a mixing value ranging from 1 (not mixed) to 0 (completely mixed) (Figure 3A). We calculated this mixing value for five different flow rates, which are indicated by their respective Peclet number, a dimensionless quantity that is directly proportional to total volumetric flow rate (Figure 3B). For each flow rate, we determined the channel length at which the dyes are 90% mixed (mixing value = 0.1), a value that could be compared between devices to evaluate mixing performance. We identified a linear relationship between the natural log of the Peclet number and the channel length needed for 90% mixing (Figure 3B inset), matching prior work,36 which is maintained over 2 orders of magnitude of flow rates (24 μL/min to 2400 μL/min).

Figure 3.

Validation of uniform mixing across all scales of microfluidic devices. Mixing characterization for microfluidic devices: single channel (A, B), single row PMD (C–F), and PMD (G–J). (A) Schematic for the mixing experiment, where FITC and rhodamine were flowed through a single channel device to quantify mixing at various channel lengths, showing the red and green plot profiles versus channel distance at the outlet (inset). Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) Quantification of mixing versus channel length for five different flow rates, where the channel length for 90% mixing (±standard error mean) is directly correlated with the natural log of the Peclet number (inset). (C) Schematic of the mixing experiment with a single row PMD consisting of 10 parallel channels. (D–E) Fluorescent images of mixing in a channel, showing the red and green plot profiles versus channel distance at the outlet (inset). Scale bars: 200 μm. (F) Comparison of the channel length required for 90% mixing (±standard error mean) for all 10 channels and the single channel device. Samples were compared by one-way ANOVA. ns: p > 0.05. (G) Schematic for the mixing experiment with the PMD. (H, I) Fluorescent images of mixing in a channel, showing the red and green plot profiles versus channel distance at the outlet (inset). Scale bars: 200 μm. (J) Comparison of the channel length required for 90% mixing (±standard error mean) for three channels across the device and the single channel device. Samples were compared by one-way ANOVA. ns: p > 0.05.

In addition to the PMD with 128 SHMs, we fabricated a single row PMD with only 10 SHMs to validate our design principles. Using the single row PMD, we quantified the channel length needed for 90% mixing and compared it to the single channel device at the same flow rate per channel (Figure 3C–F). Similarly, we used the PMD with 128 SHMs to quantify the channel length needed for 90% mixing and compared it to the single channel device at the same flow rate per channel (Figure 3G–J). Our mixing quantification for the single row PMD and PMD demonstrates that mixing efficiency is unaffected by the incorporation of 10 or 128 SHMs, validating the design of the device.

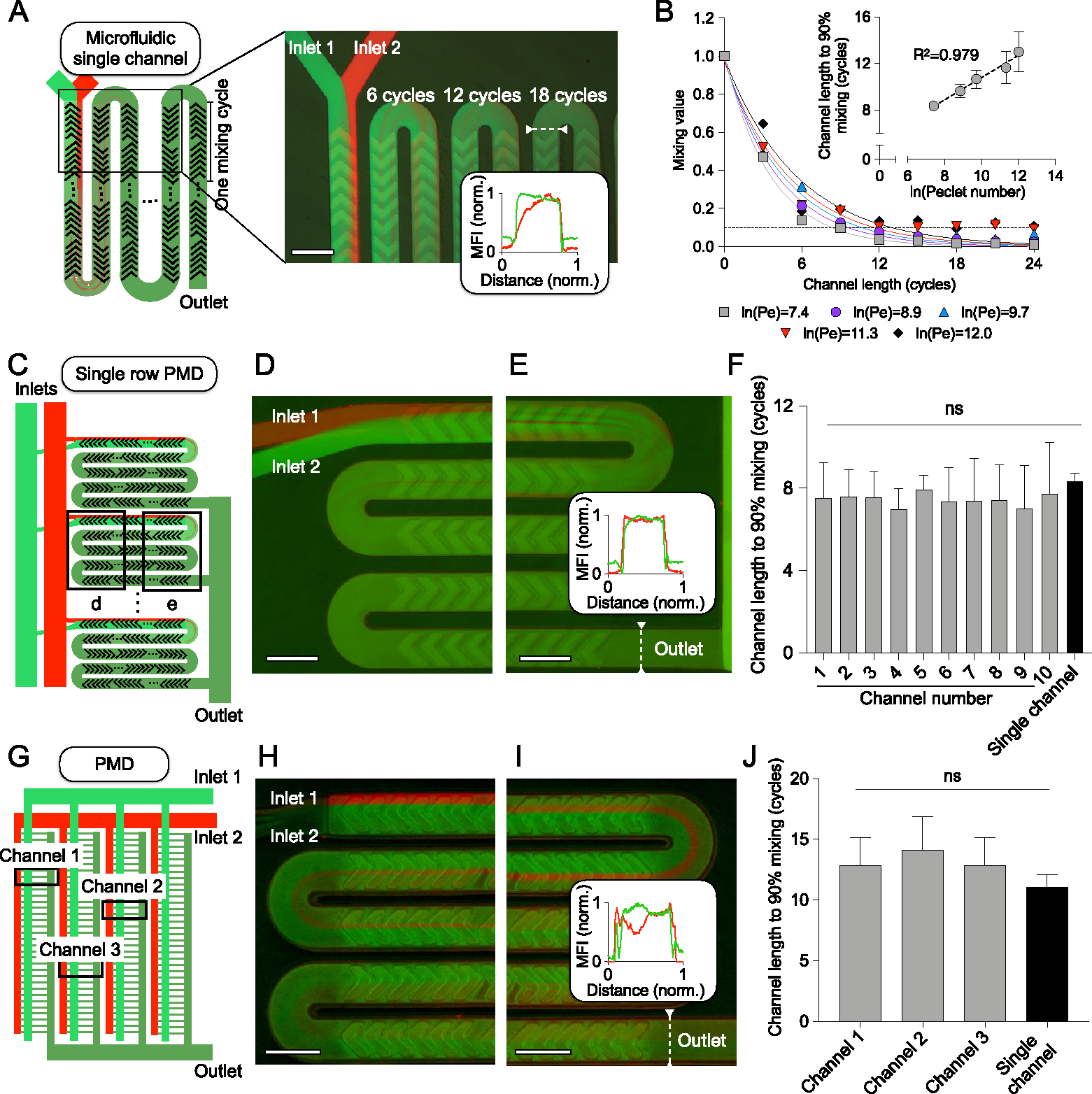

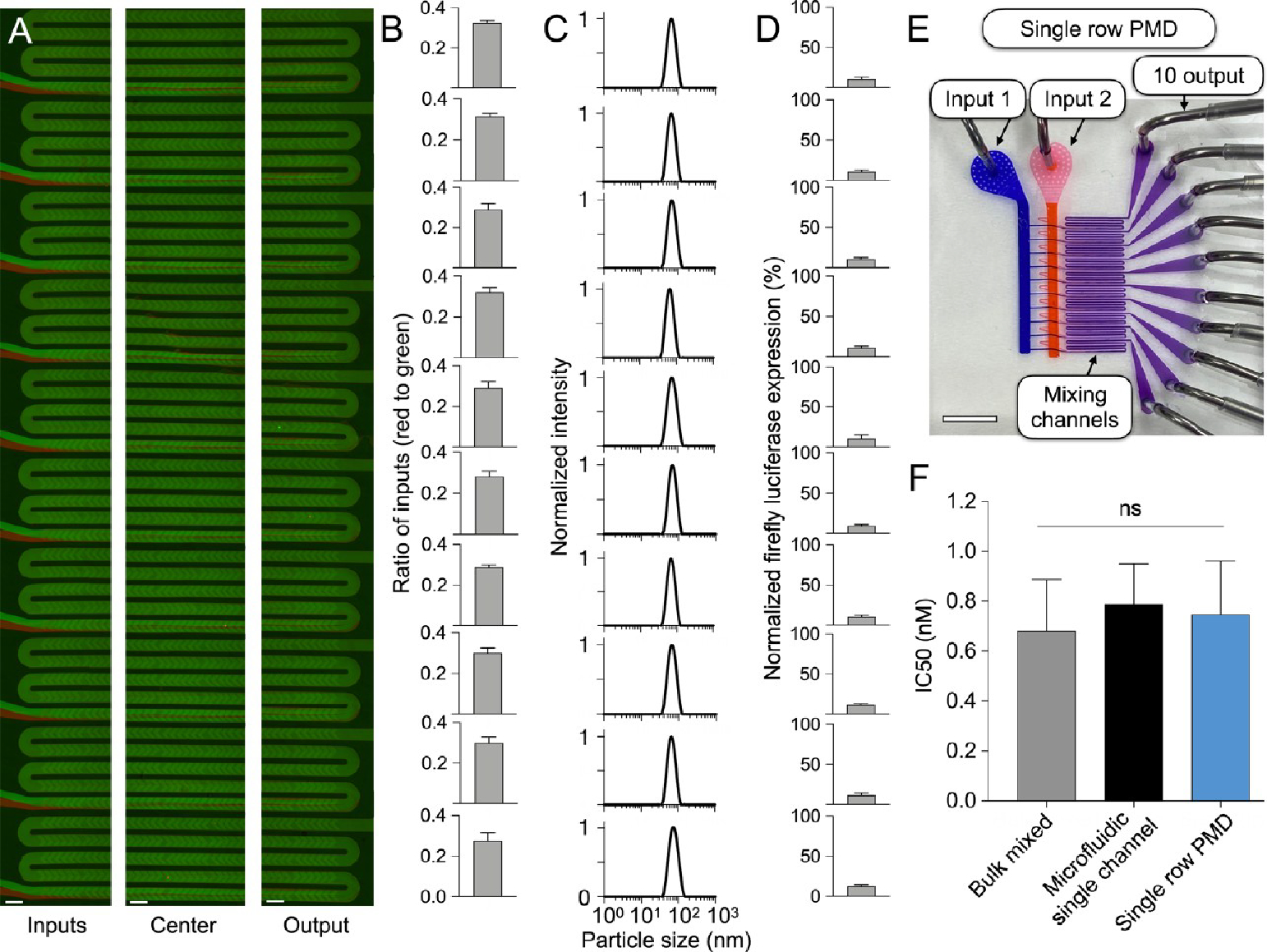

To characterize the uniformity of the geometry of our SHMs, we quantified channel heights and the flow rate ratio for each channel. By evaluating the cross sections of each channel, we determined there were no significant differences in channel heights across the device (Figure S1). To quantify the flow rate ratios for each of the channels of the single row PMD, we flowed two fluorescent dyes through the device and quantified the ratio of rhodamine to FITC for each of the 10 channels, where we found no significant differences in flow rate ratio between channels (Figure 4A,B). Here, we show that each channel has a flow rate ratio of ~0.3, which is the ratio of lipids to nucleic acids used for LNP formulations.26 Collectively, we validated the uniform fabrication and performance of the PMD to ensure it was suitable for formulating LNPs.

Figure 4.

Validation of mixing, uniform LNP physical properties, and potent RNA delivery in vitro for the single row PMD. (A) Ten mixing channels are organized in a single row, with the two inlets connected by a ladder geometry to each channel, showing the beginning (left), center (middle), and end (right) of each channel. Scale bars: 200 μm. (B) Quantification of the ratio of red to green inlets (±standard deviation) for each channel. (C) DLS curves for firefly luciferase siRNA LNPs produced from each channel. (D) Luciferase expression (±standard deviation) in HeLa cells after treatment with 5 nM of luciferase siRNA LNPs produced from each channel. Data is normalized to cells without treatment with background subtracted. n = 10. (E) Photograph of the single row PMD with two inputs (blue, orange dye) and 10 outputs, one for each mixing channel, used to collect LNPs from each channel. Scale bar: 5 mm. (F) Calculated IC50 (±standard deviation) indicates the luciferase siRNA dose needed to silence 50% of the firefly luciferase gene for each formulation method. Samples were compared by one-way ANOVA. ns: p > 0.05.

FORMULATION OF LNPs ENCAPSULATING RNAs WITH PARALLELIZED DEVICE

To validate that our PMD could formulate LNPs at a large scale without compromising the desirable physical parameters of LNPs produced by microfluidic single SHMs, we produced LNPs and evaluated their physical properties—such as size, size distribution, and encapsulation efficiency. Further, to verify that our PMD does not compromise LNP efficacy, we formulated LNPs encapsulating siRNA for in vitro screening in cell lines, as well as LNPs encapsulating either siRNA or mRNA for in vivo gene silencing or gene expression, respectively, in mice. Throughout these in vitro and in vivo studies, we demonstrate that potency is comparable between LNPs formulated by a microfluidic single channel device and PMD.

To confirm that LNP formulations were reproducible across all channels of the single row PMD, we fabricated a device with individual outputs for each of the 10 SHMs for individual analysis of LNP formulations (Figure 4E). To evaluate gene knockdown efficiency in vitro for LNPs formulated by each mixing channel, we formulated LNPs with the ionizable lipid C1–200, a gold standard lipid that is well validated for siRNA and mRNA delivery, to aid in cellular uptake as well as endosomal escape to ultimately enable potent intracellular delivery.18,54–57 To induce LNP self-assembly in the device, luciferase siRNA was rapidly mixed with a solution of lipids: C12–200, phospholipid 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), cholesterol, and lipid-PEG.18,57,58 Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis of the siRNA LNPs from each of the 10 output channels demonstrated no significant differences in size or size distribution (Figures 4C and S3). Gene silencing in vitro was evaluated using a validated screening assay19,20,59,60 where HeLa cells, modified to stably express firefly (Photinus pyralis) luciferase, were transfected with these siRNA LNPs, and the resultant reduction in luciferase expression (>80%) was comparable between LNPs formulated across the 10 SHMs (Figure 4D). Additionally, luciferase siRNA LNPs were formulated by the single row PMD, a single channel microfluidic device, and bulk mixing, where both microfluidic methods produced small (70 nm) LNPs and bulk mixing produced large (130 nm) LNPs (Figure S3). HeLa cells were transfected with LNPs generated by each of the formulation methods, and luciferase expression was quantified for different siRNA doses to determine an IC50 value (Figures 4F and S3). For these in vitro experiments, luciferase knockdown was equivalent for all formulation methods tested.

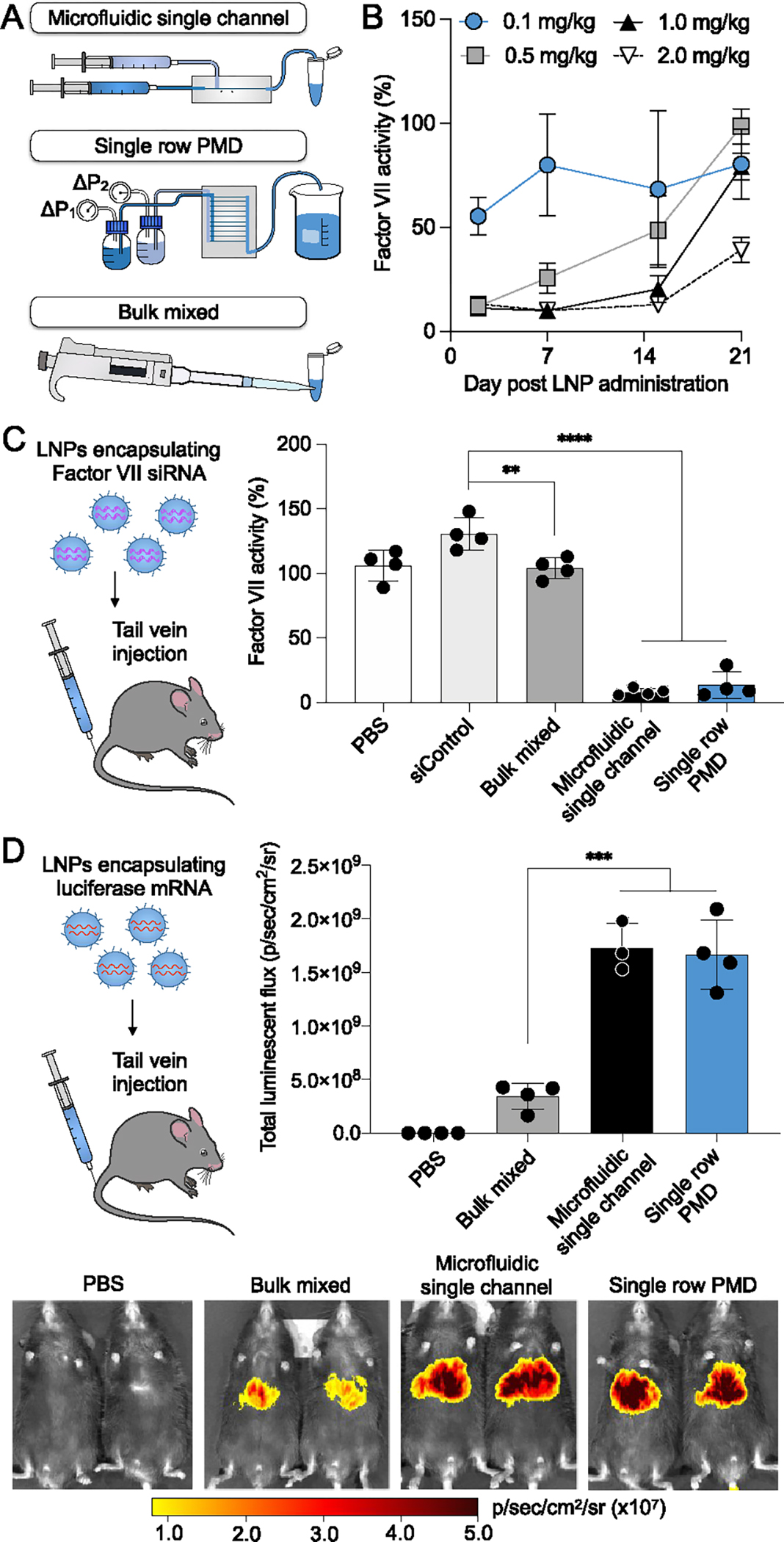

To demonstrate potent in vivo siRNA and mRNA delivery via PMD-formulated LNPs, siRNA LNPs to knockdown Factor VII and luciferase-encoding mRNA LNPs were compared to LNPs produced by a microfluidic single channel device and bulk mixing (Figure 5A). siRNA LNPs were formulated by mixing Factor VII siRNA with a solution of lipids: C12–200, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), cholesterol, and lipid-PEG (selected based on their use in previous in vivo Factor VII studies).18,19 Similarly, mRNA LNPs were formulated by mixing luciferase mRNA with a solution of lipids: C12–200, DOPE, cholesterol, and lipid-PEG, where excipients and excipient ratios were selected based on previous studies for mRNA LNP optimization.18 An initial study with siRNA LNPs formulated using a microfluidic single channel device investigated a range of doses (0.1–2.0 mg/kg) for Factor VII knockdown, where a dose of 0.1 mg/kg would achieve ~50% knockdown of Factor VII activity in plasma at 2 days post injection (Figure 5B); thus, we chose a dose of 0.2 mg/kg for our subsequent studies to ensure >50% knockdown for microfluidic-formulated LNPs. Both microfluidic methods produced Factor VII siRNA LNPs with a small size (<85 nm), whereas bulk mixing produced LNPs with a large size (>120 nm) (Figure S4). Factor VII siRNA LNPs were administered to C57BL/6 mice via tail vein injection, and Factor VII activity was quantified in plasma 2 days post injection5,19 (Figure 5C). PMD and single channel microfluidics produced LNPs that were more potent than bulk mixed LNPs, where microfluidic LNPs reduced Factor VII activity by >90% while bulk mixed LNPs minimally (20%) reduced Factor VII activity. There were no significant differences in toxicity between formulation groups as indicated by histological analysis performed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver samples (Figure S5). To show that our technology could also be used for mRNA delivery, we formulated luciferase mRNA LNPs with the three formulation methods, where both microfluidic methods produced LNPs with a small size (<85 nm) and bulk mixing produced LNPs with a large size (>140 nm) (Figure S4). These mRNA LNPs were administered to C57BL/6 mice via tail vein injection, where LNP efficacy was determined by a luminescent signal18 at 4 h post LNP administration (Figure 5D). LNPs produced by both microfluidic methods were more potent than bulk mixed LNPs, where microfluidic-formulated LNPs demonstrated a 5-fold increase of luciferase expression compared to bulk mixed LNPs. We predict that the poor performance of the bulk mixed LNPs in vivo could be attributed to its large size (>120 nm) that led to rapid blood clearance by the reticuloendothelial system and limited passage through liver fenestrations.61,62 Additionally, we observed no significant differences in toxicity as indicated by no clinically significant changes of aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) between formulation groups (Figure S6). Overall, these results demonstrate that our PMD produces LNPs at a large scale that achieve potent in vivo siRNA and mRNA delivery that are comparable to LNPs formulated using single channel microfluidics.

Figure 5.

Scalable PMD formulates LNPs with uniform physical properties for potent in vivo therapeutic RNA delivery compared to bulk mixing methods. (A) Schematic for comparison between microfluidic single channel device, single row PMD, and bulk mixing. (B) Microfluidic-formulated siRNA LNPs targeting Factor VII were delivered to C57BL/6 mice to determine the optimal dose and collection time point. LNPs were formulated with Factor VII siRNA by a microfluidic single channel device, and Factor VII activity is reported as a percentage of activity 1 day prior to LNP administration. n = 3. (C) Mice were dosed with 0.2 mg/kg of Factor VII siRNA LNPs, and Factor VII activity was quantified 48 h later. Factor VII activity is reported as a percentage of activity 1 day prior to LNP administration. *p < 0.05 (p = 0.0116); ****p < 0.0001 in unpaired t test to siControl LNP. n = 4. (D) LNPs were formulated with mRNA encoding firefly luciferase and administered to mice via tail vein injection at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg. Luminescent flux of a region of interest was quantified 4 h after LNP administration. ***p < 0.001 in unpaired t test to bulk mixed LNPs. n = 3–4.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have developed a simple and scalable PMD fabricated using PDMS to produce highly monodisperse LNPs on a scale (1×, 10× and 128×) relevant for clinical applications, which is >100× the throughput of a single microfluidic device.26 By using double-sided imprinting and incorporating upstream flow resistors to decouple the design of the mixing channels and the overall resistance of the device, we fabricated devices that are inexpensive and can be tailored to the applications of potentially any user. This technology has the potential to address the challenge of scalability for microfluidic formulation of LNPs, where the total throughput scales directly with the number of incorporated mixing channels (Figure 1C). While alternative methods like T-junction mixing can produce LNPs at clinically relevant rates (2.4–3.6 L/h), this method is not fully scalable since it cannot produce small volumes (μL) needed for discovery experiments.46–48 Additionally, Precision NanoSystem’s NanoAssemblr platform can also achieve clinically relevant rates (>10 L/h) with desirable LNP properties49 but requires multiple devices operating independently, which is not easily scalable to >100x since each device requires macroscopic manifolds to deliver fluids to each device separately. Overall, our proof-of-concept scalable PMD technology may potentially address key unmet needs of scalable microfluidic processes for LNP formulation, by generating precisely engineered nanomaterials that can potentially be economically scaled across all aspects of the development of LNP formulations, including RNA therapeutics and vaccines.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.J.M. acknowledges support from a US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s New Innovator Award (DP2 TR002776), a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award at the Scientific Interface (CASI), a grant from the American Cancer Society (129784-IRG-16–188-38-IRG), and the National Institutes of Health (NCI R01 CA241661, NCI R37 CA244911, and NIDDK R01 DK123049). D.I. Acknowledges support from the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation (Reconstructing Concussion), the National Institutes of Health (R33 CA206907, R21-EB023989, RM1 HG010023, R21 MH118170, R61 AI147406), the Department of Defense (W81XWH1920002), and the Pennsylvania Department of Health (4100077083). S.J.S. is supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (Award 1845298). C.C.W., L.W., and J.M.W. acknowledge support from a private funding source. This work was carried out in part at the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, which is supported by the NSF National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Program under grant NNCI-1542153.

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c01353

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): J.M.W. is a paid advisor to and holds equity in Scout Bio and Passage Bio; he holds equity in Surmount Bio; he also has sponsored research agreements with Amicus Therapeutics, Biogen, Elaaj Bio, Janssen, Moderna, Passage Bio, Scout Bio, Surmount Bio, and Ultragenyx, which are licensees of Penn technology. J.M.W. and L.W. are inventors on patents that have been licensed to various biopharmaceutical companies and for which they may receive payments. S.J.S., S.Y., D.I., and M.J.M. are inventors on a patent related to this work filed by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania (63/131,008). D.W. is an inventor on several patents related to this work filed by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania (11/990,646; 13/585,517; 13/839,023; 13/839,155; 14/456,302; 15/339,363; and 16/299,202). The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c01353.

Materials and methods for device design, device fabrication, experimental setup, mixing characterization, lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulation and characterization, siRNA delivery to HeLa cells in vitro, in vivo LNP studies, statistical analysis; PMD design and validation of uniform fabrication; characterization of single stranded DNA LNPs formulated by the single row PMD; characterization of luciferase siRNA LNPs and transfection in vitro; characterization of Factor VII siRNA LNPs and luciferase mRNA LNPs; mouse liver histopathology; liver toxicity assays (PDF)

Contributor Information

Sarah J. Shepherd, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States

Claude C. Warzecha, Gene Therapy Program, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States

Sagar Yadavali, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

Rakan El-Mayta, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

Mohamad-Gabriel Alameh, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

Lili Wang, Gene Therapy Program, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

Drew Weissman, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

James M. Wilson, Gene Therapy Program, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States

David Issadore, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States; Department of Electrical and Systems Engineering and Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

Michael J. Mitchell, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States; Abramson Cancer Center, Perelman School of Medicine, Institute for Immunology, Perelman School of Medicine, Cardiovascular Institute, Perelman School of Medicine, and Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Burnett JC; Rossi JJ RNA-Based Therapeutics: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19 (1), 60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Setten RL; Rossi JJ; Han S. p. The Current State and Future Directions of RNAi-Based Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2019, 18, 421–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Patel S; Ryals RC; Weller KK; Pennesi ME; Sahay G Lipid Nanoparticles for Delivery of Messenger RNA to the Back of the Eye. J. Controlled Release 2019, 303 (March), 91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Yin H; Kanasty RL; Eltoukhy AA; Vegas AJ; Dorkin JR; Anderson DG Non-Viral Vectors for Gene-Based Therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Semple SC; Akinc A; Chen J; Sandhu AP; Mui BL; Cho CK; Sah DWY; Stebbing D; Crosley EJ; Yaworski E; Hafez IM; Dorkin JR; Qin J; Lam K; Rajeev KG; Wong KF; Jeffs LB; Nechev L; Eisenhardt ML; Jayaraman M; Kazem M; Maier MA; Srinivasulu M; Weinstein MJ; Chen Q; Alvarez R; Barros SA; De S; Klimuk SK; Borland T; Kosovrasti V; Cantley WL; Tam YK; Manoharan M; Ciufolini MA; Tracy MA; De Fougerolles A; MacLachlan I; Cullis PR; Madden TD; Hope MJ Rational Design of Cationic Lipids for SiRNA Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28 (2), 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chen G; Abdeen AA; Wang Y; Shahi PK; Robertson S; Xie R; Suzuki M; Pattnaik BR; Saha K; Gong S A Biodegradable Nanocapsule Delivers a Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein Complex for in Vivo Genome Editing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14 (10), 974–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zimmermann TS; Lee ACH; Akinc A; Bramlage B; Bumcrot D; Fedoruk MN; Harborth J; Heyes JA; Jeffs LB; John M; Judge AD; Lam K; McClintock K; Nechev LV; Palmer LR; Racie T; Röhl I; Seiffert S; Shanmugam S; Sood V; Soutschek J; Toudjarska I; Wheat AJ; Yaworski E; Zedalis W; Koteliansky V; Manoharan M; Vornlocher HP; MacLachlan I RNAi-Mediated Gene Silencing in Non-Human Primates. Nature 2006, 441 (1), 111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Debacker AJ; Voutila J; Catley M; Blakey D; Habib N Delivery of Oligonucleotides to the Liver with GalNAc: From Research to Registered Therapeutic Drug. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28 (8), 1759–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Barba AA; Bochicchio S; Dalmoro A; Lamberti G Lipid Delivery Systems for Nucleic-Acid-Based-Drugs: From Production to Clinical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11 (8), 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Baden LR; El Sahly HM; Essink B; Kotloff K; Frey S; Novak R; Diemert D; Spector SA; Rouphael N; Creech CB; McGettigan J; Khetan S; Segall N; Solis J; Brosz A; Fierro C; Schwartz H; Neuzil K; Corey L; Gilbert P; Janes H; Follmann D; Marovich M; Mascola J; Polakowski L; Ledgerwood J; Graham BS; Bennett H; Pajon R; Knightly C; Leav B; Deng W; Zhou H; Han S; Ivarsson M; Miller J; Zaks T Efficacy and Safety of the MRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Polack FP; Thomas SJ; Kitchin N; Absalon J; Gurtman A; Lockhart S; Pérez JL; Pérez Marc G; Moreira ED; Zerbini C; Bailey R; Swanson KA; Roychoudhury S; Koury K; Li P; Kalina WV; Cooper D; Frenck RW; Hammitt LL; Tuüreci Ö; Nell H; Schaefer A; Ünal S; Tresnan DB; Mather S; Dormitzer PR; Şahin U; Jansen KU; Gruber WC. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2MRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383 (27), 2603–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Milane L; Amiji M Clinical Approval of Nanotechnology-Based SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccines: Impact on Translational Nanomedicine. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2021, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Guan S; Rosenecker J Nanotechnologies in Delivery of MRNA Therapeutics Using Nonviral Vector-Based Delivery Systems. Gene Ther. 2017, 24 (3), 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Davidson BL; McCray PB Current Prospects for RNA Interference-Based Therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12 (5), 329–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Puri A; Loomis K; Smith B; Lee J-H; Yavlovich A; Heldman E; Blumenthal R Lipid-Based Nanoparticles as Pharmaceutical Drug Carriers: From Concepts to Clinic. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2009, 26 (6), 523–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kulkarni JA; Cullis PR; Van Der Meel R Lipid Nanoparticles Enabling Gene Therapies: From Concepts to Clinical Utility. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2018, 28 (3), 146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Akinc A; Maier MA; Manoharan M; Fitzgerald K; Jayaraman M; Barros S; Ansell S; Du X; Hope MJ; Madden TD; Mui BL; Semple SC; Tam YK; Ciufolini M; Witzigmann D; Kulkarni JA; van der Meel R; Cullis PR The Onpattro Story and the Clinical Translation of Nanomedicines Containing Nucleic Acid-Based Drugs. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14 (12), 1084–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kauffman KJ; Dorkin JR; Yang JH; Heartlein MW; Derosa F; Mir FF; Fenton OS; Anderson DG Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for MRNA Delivery in Vivo with Fractional Factorial and Definitive Screening Designs. Nano Lett. 2015, 15 (11), 7300–7306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ball RL; Hajj KA; Vizelman J; Bajaj P; Whitehead KA Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for Enhanced Co-Delivery of SiRNA and MRNA. Nano Lett. 2018, 18 (6), 3814–3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Love KT; Mahon KP; Levins CG; Whitehead KA; Querbes W; Dorkin JR; Qin J; Cantley W; Qin LL; Racie T; Frank-Kamenetsky M; Yip KN; Alvarez R; Sah DWY; de Fougerolles A; Fitzgerald K; Koteliansky V; Akinc A; Langer R; Anderson DG Lipid-like Materials for Low-Dose, in Vivo Gene Silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107 (5), 1864–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Evers MJW; Kulkarni JA; van der Meel R; Cullis PR; Vader P; Schiffelers RM State-of-the-Art Design and Rapid-Mixing Production Techniques of Lipid Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery. Small Methods 2018, 2 (9), 1700375. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Shepherd SJ; Issadore D; Mitchell MJ Microfluidic Formulation of Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials 2021, 274 (March), 120826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Swingle KL; Hamilton AG; Mitchell MJ Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of MRNA Therapeutics and Vaccines. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Garg S; Heuck G; Ip S; Ramsay E Microfluidics: A Transformational Tool for Nanomedicine Development and Production. J. Drug Target. 2016, 24 (9), 821–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Maurer N; Wong KF; Stark H; Louie L; McIntosh D; Wong T; Scherrer P; Semple SC; Cullis PR Spontaneous Entrapment of Polynucleotides upon Electrostatic Interaction with Ethanol-Destabilized Cationic Liposomes. Biophys. J. 2001, 80 (5), 2310–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chen D; Love KT; Chen Y; Eltoukhy AA; Kastrup C; Sahay G; Jeon A; Dong Y; Whitehead KA; Anderson DG Rapid Discovery of Potent SiRNA-Containing Lipid Nanoparticles Enabled by Controlled Microfluidic Formulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (16), 6948–6951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Roces CB; Lou G; Jain N; Abraham S; Thomas A; Halbert GW; Perrie Y Manufacturing Considerations for the Development of Lipid Nanoparticles Using Microfluidics. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12 (11), 1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Valencia P; Farokhzad O; Karnik R; Langer R Microfluidic Technologies for Accelerating the Clinical Translation of Nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 623–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Belliveau NM; Huft J; Lin PJ; Chen S; Leung AK; Leaver TJ; Wild AW; Lee JB; Taylor RJ; Tam YK; Hansen CL; Cullis PR Microfluidic Synthesis of Highly Potent Limit-Size Lipid Nanoparticles for in Vivo Delivery of SiRNA. Mol. Ther.–Nucleic Acids 2012, 1 (8), No. e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Jahn A; Vreeland WN; Gaitan M; Locascio LE Controlled Vesicle Self-Assembly in Microfluidic Channels with Hydrodynamic Focusing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (9), 2674–2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Jahn A; Stavis SM; Hong JS; Vreeland WN; Devoe DL; Gaitan M Microfluidic Mixing and the Formation of Nanoscale Lipid Vesicles. ACS Nano 2010, 4 (4), 2077–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Krzysztoń R; Salem B; Lee DJ; Schwake G; Wagner E; Rädler JO Microfluidic Self-Assembly of Folate-Targeted Monomolecular SiRNA-Lipid Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2017, 9 (22), 7442–7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hood RR; Devoe DL; Atencia J; Vreeland WN; Omiatek DM A Facile Route to the Synthesis of Monodisperse Nanoscale Liposomes Using 3D Microfluidic Hydrodynamic Focusing in a Concentric Capillary Array. Lab Chip 2014, 14 (14), 2403–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Crawford R; Dogdas B; Keough E; Haas RM; Wepukhulu W; Krotzer S; Burke PA; Sepp-Lorenzino L; Bagchi A; Howell BJ Analysis of Lipid Nanoparticles by Cryo-EM for Characterizing SiRNA Delivery Vehicles. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 403 (1–2), 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Gindy ME; Feuston B; Glass A; Arrington L; Haas RM; Schariter J; Stirdivant SM Stabilization of Ostwald Ripening in Low Molecular Weight Amino Lipid Nanoparticles for Systemic Delivery of SiRNA Therapeutics. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2014, 11 (11), 4143–4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Stroock AD; Dertinger SKW; Ajdari A; Mezic I; Stone HA; Whitesides GM Chaotic Mixer for Microchannels. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2002, 295, 647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kis Z; Kontoravdi C; Shattock R; Shah N Resources, Production Scales and Time Required for Producing RNA Vaccines for the Global Pandemic Demand. Vaccines 2021, 9 (1), 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Romanowsky MB; Abate AR; Rotem A; Holtze C; Weitz DA High Throughput Production of Single Core Double Emulsions in a Parallelized Microfluidic Device. Lab Chip 2012, 12 (4), 802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Muluneh M; Issadore D Hybrid Soft-Lithography/Laser Machined Microchips for the Parallel Generation of Droplets. Lab Chip 2013, 13 (24), 4750–4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Toth MJ; Kim T; Kim YT Robust Manufacturing of Lipid-Polymer Nanoparticles through Feedback Control of Parallelized Swirling Microvortices. Lab Chip 2017, 17 (16), 2805–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lim JM; Bertrand N; Valencia PM; Rhee M; Langer R; Jon S; Farokhzad OC; Karnik R Parallel Microfluidic Synthesis of Size-Tunable Polymeric Nanoparticles Using 3D Flow Focusing towards in Vivo Study. Nanomedicine 2014, 10 (2), 401–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Jeong HH; Yelleswarapu VR; Yadavali S; Issadore D; Lee D Kilo-Scale Droplet Generation in Three-Dimensional Monolithic Elastomer Device (3D MED). Lab Chip 2015, 15 (23), 4387–4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Tsao CW Polymer Microfluidics: Simple, Low-Cost Fabrication Process Bridging Academic Lab Research to Commercialized Production. Micromachines 2016, 7 (12), 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lee JN; Park C; Whitesides GM Solvent Compatibility of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane)-Based Microfluidic Devices. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75 (23), 6544–6554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Leung AKK; Hafez IM; Baoukina S; Belliveau NM; Zhigaltsev IV; Afshinmanesh E; Tieleman DP; Hansen CL; Hope MJ; Cullis PR Lipid Nanoparticles Containing SiRNA Synthesized by Microfluidic Mixing Exhibit an Electron-Dense Nanostructured Core. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116 (34), 18440–18450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Abrams MT; Koser ML; Seitzer J; Williams SC; Dipietro MA; Wang W; Shaw AW; Mao X; Jadhav V; Davide JP; Burke PA; Sachs AB; Stirdivant SM; Sepp-Lorenzino L Evaluation of Efficacy, Biodistribution, and Inflammation for a Potent SiRNA Nanoparticle: Effect of Dexamethasone Co-Treatment. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18 (1), 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Jeffs LB; Palmer LR; Ambegia EG; Giesbrecht C; Ewanick S; MacLachlan I A Scalable, Extrusion-Free Method for Efficient Liposomal Encapsulation of Plasmid DNA. Pharm. Res. 2005, 22 (3), 362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Heyes J; Palmer L; Bremner K; MacLachlan I Cationic Lipid Saturation Influences Intracellular Delivery of Encapsulated Nucleic Acids. J. Controlled Release 2005, 107 (2), 276–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Webb C; Forbes N; Roces CB; Anderluzzi G; Lou G; Abraham S; Ingalls L; Marshall K; Leaver TJ; Watts JA; Aylott JW; Perrie Y Using Microfluidics for Scalable Manufacturing of Nanomedicines from Bench to GMP: A Case Study Using Protein-Loaded Liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 582 (April), 119266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Yadavali S; Lee D; Issadore D Robust Microfabrication of Highly Parallelized Three-Dimensional Microfluidics on Silicon. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9 (1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Yadavali S; Jeong HH; Lee D; Issadore D Silicon and Glass Very Large Scale Microfluidic Droplet Integration for Terascale Generation of Polymer Microparticles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Dressaire E; Sauret A Clogging of Microfluidic Systems. Soft Matter 2017, 13 (1), 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Schroeder A; Levins CG; Cortez C; Langer R; Anderson DG Lipid-Based Nanotherapeutics for SiRNA Delivery. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 267 (1), 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Yin H; Song CQ; Dorkin JR; Zhu LJ; Li Y; Wu Q; Park A; Yang J; Suresh S; Bizhanova A; Gupta A; Bolukbasi MF; Walsh S; Bogorad RL; Gao G; Weng Z; Dong Y; Koteliansky V; Wolfe SA; Langer R; Xue W; Anderson DG Therapeutic Genome Editing by Combined Viral and Non-Viral Delivery of CRISPR System Components in Vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34 (3), 328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Whitehead KA; Dorkin JR; Vegas AJ; Chang PH; Veiseh O; Matthews J; Fenton OS; Zhang Y; Olejnik KT; Yesilyurt V; Chen D; Barros S; Klebanov B; Novobrantseva T; Langer R; Anderson DG Degradable Lipid Nanoparticles with Predictable in Vivo SiRNA Delivery Activity. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Oberli MA; Reichmuth AM; Dorkin JR; Mitchell MJ; Fenton OS; Jaklenec A; Anderson DG; Langer R; Blankschtein D Lipid Nanoparticle Assisted MRNA Delivery for Potent Cancer Immunotherapy. Nano Lett. 2017, 17 (3), 1326–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Billingsley MM; Singh N; Ravikumar P; Zhang R; June CH; Mitchell MJ Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated MRNA Delivery for Human CAR T Cell Engineering. Nano Lett. 2020, 20 (3), 1578–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Guimaraes PPG; Zhang R; Spektor R; Tan M; Chung A; Billingsley MM; El-Mayta R; Riley RS; Wang L; Wilson JM; Mitchell MJ Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticles Encapsulating Barcoded MRNA for Accelerated in Vivo Delivery Screening. J. Controlled Release 2019, 316, 404–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Akinc A; Zumbuehl A; Goldberg M; Leshchiner ES; Busini V; Hossain N; Bacallado SA; Nguyen DN; Fuller J; Alvarez R; Borodovsky A; Borland T; Constien R; De Fougerolles A; Dorkin JR; Narayanannair Jayaprakash K; Jayaraman M; John M; Koteliansky V; Manoharan M; Nechev L; Qin J; Racie T; Raitcheva D; Rajeev KG; Sah DWY; Soutschek J; Toudjarska I; Vornlocher HP; Zimmermann TS; Langer R; Anderson DG A Combinatorial Library of Lipid-like Materials for Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26 (5), 561–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Ball R; Bajaj P; Whitehead KA Achieving Long-Term Stability of Lipid Nanoparticles: Examining the Effect of PH, Temperature, and Lyophilization. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Witzigmann D; Uhl P; Sieber S; Kaufman C; Einfalt T; Schöneweis K; Grossen P; Buck J; Ni Y; Schenk SH; Hussner J; Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE; Québatte G; Mier W; Urban S; Huwyler J Optimization-by-Design of Hepatotropic Lipid Nanoparticles Targeting the Sodium-Taurocholate Cotransporting Polypeptide. eLife 2019, 8, 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Witzigmann D; Kulkarni JA; Leung J; Chen S; Cullis PR; van der Meel R Lipid Nanoparticle Technology for Therapeutic Gene Regulation in the Liver. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2020, 159, 344–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.