Abstract

This work describes the synthesis and pharmacological and toxicological evaluation of melanostatin (MIF-1) bioconjugates with amantadine (Am) via a peptide linkage. The data from the functional assays at human dopamine D2 receptors (hD2R) showed that bioconjugates 1 (EC50 = 26.39 ± 3.37 nM) and 2 (EC50 = 17.82 ± 4.24 nM) promote a 3.3- and 4.9-fold increase of dopamine potency, respectively, at 0.01 nM, with no effect on the efficacy (Emax = 100%). In this assay, MIF-1 was only active at the highest concentration tested (EC50 = 23.64 ± 6.73 nM, at 1 nM). Cytotoxicity assays in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells showed that both MIF-1 (94.09 ± 5.75%, p < 0.05) and carbamate derivative 2 (89.73 ± 4.95%, p < 0.0001) exhibited mild but statistical significant toxicity (assessed through the MTT reduction assay) at 200 μM, while conjugate 1 was found nontoxic at this concentration.

Keywords: Amantadine, Melanostatin, Parkinson’s Disease, Peptide Bioconjugates, Positive Allosteric Modulators

Melanocyte-stimulating hormone release-inhibiting factor-1 (MIF-1, Figure 1), also known as melanostatin, is a short hypothalamic neuropeptide with the primary structure of l-prolyl-l-leucylglycinamide and is responsible for regulating the release of the melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) in the hypophysis.1,2 Besides the MSH-related activity, MIF-1 is known to increase the binding of agonists to dopamine receptor subtypes D2L, D2S, and D4, of which it exhibits higher affinity toward the D2L receptor subtype (present in postsynaptic membranes) with no effect on the binding to D1 and D3 subtypes.3 This represents one of the few examples where a known endogenous molecule has demonstrated allosteric receptor-modulating activity.4 In fact, MIF-1 behaves as a positive allosteric modulator (PAM), promoting the binding of agonists in the presence of the D2L receptor/G protein complex.3 Upon binding, MIF-1 stabilizes the high-affinity state of the D2 receptors (D2R), thereby reducing the concentration of agonists required for their functional activation.3,5−7

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of MIF-1, Am, and MIF-1-based bioconjugates 1 and 2.

Because of its pharmacological repertoire, MIF-1 has a therapeutical potential in neurological disorders associated with the D2R, such as depression,8 tardive dyskinesia, restless legs syndrome,9 and Parkinson’s disease (PD).10 In fact, MIF-1 is one of the few peptides with a partially saturable influx system at the blood–brain barrier (BBB) allowing it to accumulate in the central nervous system (CNS).11 Using [3H]-MIF-1, it was found that the influx rate into the CNS was almost 100 times greater than that of [3H]-morphine.11

Clinical assays demonstrated that MIF-1, alone, has the potential to alleviate the motor symptoms of PD,12,13 to potentiate the effect of levodopa when used in a cotherapy regimen,14 and to reduce the levodopa-induced dyskinesia.15 Despite its great potential, pharmacokinetic issues associated with this neuropeptide (e.g., low gastrointestinal absorption and lability toward CNS proteases) hinder the progression of clinical assays and its use in PD.16−18 Over the years, several strategies have been employed to improve the stability and activity of MIF-1, including the development of peptidomimetics,19−31 and chemical conjugation with a sinapic acid at the N-terminal and biogenic amines as spacers at the C-terminal position.32

Adamantane, formally tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane, is a rigid hydrocarbon scaffold that has gained momentum in medicinal chemistry as a strategy to enhance the lipophilicity and stability of drugs, thereby improving their pharmacokinetic properties, including the permeability of modified compounds through the BBB.33,34 This “lipophilic bullet” is being used as an add-on to modify known pharmacophores.35 Incorporation of the adamantane moiety into neuropeptides and related signaling molecules frequently provides increased selectivity for receptor subtypes with improved stability in vivo.36,37 Additionally, the rigid hydrocarbon is known to protect functional groups present in its proximity from metabolic cleavage, thereby further improving the time of action of peptide-derived drugs.35 Furthermore, it is “biocompatible”, as metabolism can take place in the liver so that toxic effects associated with its accumulation upon chronic treatment are not to be expected.35

Among adamantane-based drugs, adamantane-1-amine, also known as amantadine (Am, Figure 1), has found application in the context of diseases affecting the CNS after it has been serendipitously discovered to control motor symptoms (rigidity, tremor, and akinesia) in a 58-year-old woman with moderately severe bilateral PD, as reported by Schwab and co-workers in 1969.38 These findings were subsequently consubstantiated in clinical trials,39−42 thereby demonstrating that the administration of Am is considered safe since the adverse effects described were weak and reversible.35,42 Importantly, considering that the first-line PD treatment, levodopa/carbidopa, is known to induce motor fluctuations, Am is able to delay the onset of the levodopa-induced dyskinesia when used in cotherapy.43

In doses of 100–200 mg/day, Am decreases the severity of end-of-dose deterioration (wearing-off) in chronically treated PD patients44 and is effective regardless of the duration of the disease and the duration of previous treatments.45 Currently, Am hydrochloride (brand names: Gocovri, Osmolex ER, Symadine, and Symmetrel) is used for the treatment of dyskinesia associated with parkinsonism.46

Considering the pharmacokinetic advantages of adamantane-based scaffolds into peptide motifs and the relevance of Am in PD therapy, this scaffold was selected as an appropriate “lipophilic bullet” for exploring bioconjugation with MIF-1 neuropeptide. After the design and organic synthesis of novel bioconjugates, their allosteric modulatory activity was characterized by functional assays at the hD2R, and their cytotoxic profile was evaluated in human-derived differentiated neuronal SH-SY5Y cells.

Design

Previous conjugation strategies explored for MIF-1 at the N-terminal position resulted in analogs with decreased biological activity.32 In this sense, grafting of Am was envisioned at the C-terminal position instead for the assembly of the MIF-1-Am bioconjugate (1, Figure 1) by peptide coupling. Interestingly, the literature describes tert-butyl carbamate (Boc) derivatives of MIF-1 as potent PAM molecules of the D2R.47 Regarding the importance of organic carbamate groups as key structural motifs in many approved drugs and prodrugs with improved resistance toward proteolysis and enhanced lipophilicity,48 Boc-MIF-1-Am (2, Figure 1) was also considered and included in the pharmacological and toxicologic screenings.

Organic Chemistry

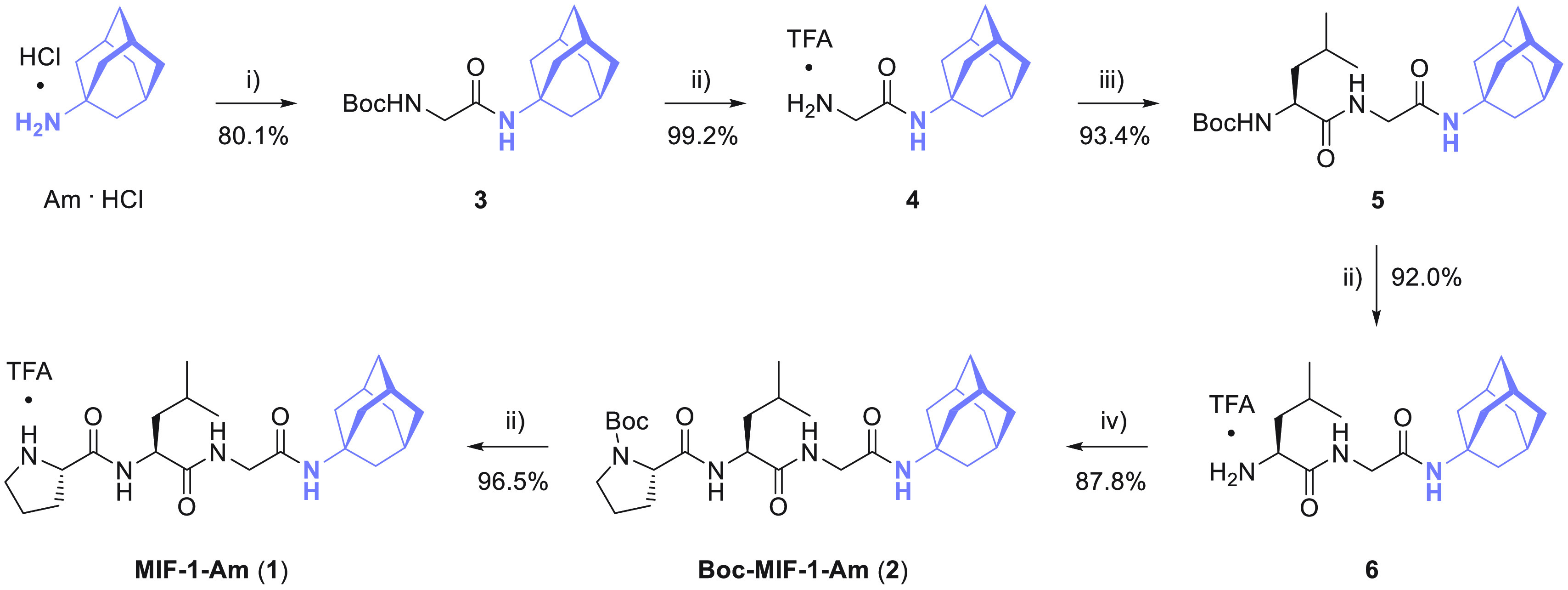

The chemical strategy followed to synthesize the MIF-1-Am (1) conjugate is depicted in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Chemical Strategy for the Assembly of MIF-1-Am (1) and Boc-MIF-1-Am (2) Bioconjugates.

Reagents and conditions: (i) Boc-Gly-OSu, Et3N, anhydrous CH2Cl2; (ii) TFA, anhydrous CH2Cl2; (iii) Boc-l-Leu-OSu, Et3N, anhydrous CH2Cl2; (iv) Boc-l-Pro-OH, TBTU, Et3N, anhydrous CH2Cl2.

First, following a C-to-N synthesis strategy in solution phase, Am hydrochloride was coupled with Boc-protected glycine preactivated as succinimidyl ester (Boc-Gly-OSu) in the presence of triethylamine (Et3N) to afford carbamate 3 with 80.1% yield. Subsequently, removal of the N-Boc protecting group was performed by acidolysis using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to deliver 4 as a trifluoroacetate salt with a 99.2% yield. Upon reaction of 4 with a preactivated Boc-protected l-leucine derivative in the form of succinimidyl ester (Boc-l-Leu-OSu), functionalized dipeptide 5 was obtained with a 93.4% yield. Acidolysis of 5 with TFA afforded dipeptide 6 in 92.0% yield. Then, Boc-l-proline (Boc-l-Pro-OH) was activated with 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate (TBTU) as the peptide coupling reagent in the presence of Et3N to perform the amidation reaction with 6, affording tripeptide 2 in 87.8% yield. Finally, bioconjugate 1 was obtained by removal of the N-Boc group using TFA in 96.5% yield. Following this protocol, peptide conjugate 1 was synthesized in 58% global yield.

Structural elucidation of 1 and 2 was performed by 1D (1H, 13C{1H}, and DEPT-135) and 2D NMR (COSY, HSQC) to corroborate the success of the bioconjugation strategy (Figures S9–S16), which was further confirmed by high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-HRMS, Figures S17 and S18).

Determination of the log Po/w

To study the impact of bioconjugation of MIF-1 with Am on lipophilicity, the partition coefficient between octan-1-ol and water (log Po/w) of MIF-1 and bioconjugates 1 and 2 was performed through the classical shake-flask method, as previously described.49 While MIF-1 and 2 gave clear phases after vigorous shaking, in the case of bioconjugate 1, it was found that the aqueous phase was turbid even after resting for 1 week. As such, the experimental log Po/w was not possible to determine for this compound. The results obtained corroborate that the bioconjugation strategy greatly improved the lipophilicity of MIF-1, with bioconjugate 2 displaying higher affinity to the organic phase than MIF-1, which mainly rests at the aqueous phase (log Po/w MIF = −0.56 ± 0.04 vs log Po/w2 = 2.62 ± 0.12). These results are in agreement with the in silico log Po/w predictions using Cheminformatics software available at SwissADME (Table S1).50,51

Dopamine D2 Receptor Functional Assays

After in silico evaluation of these compounds as potential aggregators and/or pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS),52 functional assays were conducted for conjugates 1 and 2 in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing the human D2R to characterize their PAM activity by determination of the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) and maximal effect (Emax). The assay is performed in the presence of dopamine (DA) to measure the inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) accumulation in response to D2R activation by homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF).21,23

Conjugates 1 and 2 were initially screened between 0.01 nM and 10 μM. The results for DA potentiation (0.1 μM) exerted by conjugates 1 and 2 are shown in Figure 2 and are expressed as the percentage of increase in the activity of 0.1 μM DA.

Figure 2.

Increase in the 0.1 μM DA effect triggered by conjugates 1 and 2 at different concentrations (concentration–response curve of MIF-1 included for comparative purposes). Data points represent the mean, and vertical bars represent the standard deviation of three independent measurements. Student’s t-test was performed for the statistical analyses: level of significance *p < 0.05.

In this assay, MIF-1 exhibits the typical biphasic or bell-shaped concentration–response curve (Figure 2).21,23 This particular feature is widely described in the literature,3,19,22,26,53−59 including in vivo animal experiments,60−62 and human clinical studies using MIF-1.12,63,64 Delightfully, conjugates 1 and 2 statistically increased the DA effect by 10.3 ± 5.2% and 15.3 ± 6.3% at 0.01 nM (*p < 0.05), respectively, while MIF-1 exhibited a maximum DA effect at higher concentrations (31.9 ± 17.6% at 10 nM, *p < 0.05).

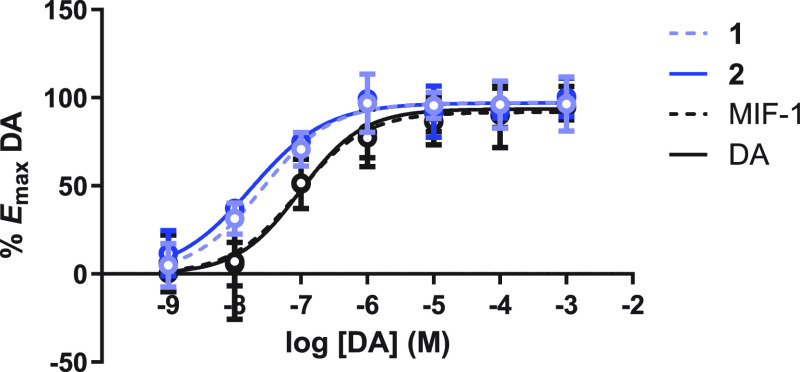

Concentration–response curves of DA were obtained in the presence and absence of MIF-1 and conjugates 1 and 2, and the data generated was normalized to Emax of DA following a protocol previously described in our research group.21,23 The results are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Concentration–response curves of DA + 0.01 nM MIF-1 and conjugates 1 and 2 (concentration–response curve of DA included). Data points represent the mean, and vertical bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments done in duplicate measurements.

In this assay, the EC50 obtained for DA alone was 87.08 ± 24.87 nM. In the presence of MIF-1 conjugates 1 and 2 at 0.01 nM (Figure 3), the DA concentration–response curves show a 3.3- and 4.9-fold increase of DA potency, respectively (EC50 = 26.39 ± 3.37 nM for 1 and EC50 = 17.82 ± 4.24 nM for 2), with no effect on the efficacy (Emax = 100% for 1 and 2). In this assay, MIF-1 did not affect DA potency at 0.01 nM (EC50 was similar to that of DA alone).

Interestingly, in these experiments, the parent neuropeptide demonstrated PAM activity at the highest concentration tested (1 nM, Figure S19), which promoted a 3.7-fold increase of DA potency (EC50 = 23.64 ± 6.73 nM, 1 nM) with no effect on the efficacy (Emax = 100%). At this concentration (1 nM), conjugates 1 and 2 were devoid of PAM activity. Altogether, these findings indicate that conjugates 1 and 2 increase the potency of DA at lower concentrations than MIF-1, thus being considered potent PAM molecules.

To validate the PAM mechanism, conjugates 1 and 2 were tested for agonist activity in the absence of DA at the human D2R between 1 nM to 1 μM (Figure 4) by using DA as a positive control.

Figure 4.

Concentration–response curves of conjugates 1 and 2 at human D2R (concentration–response curve of DA included for comparison). Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three independent measurements.

The results obtained in Figure 4 show that both conjugates 1 and 2 display no intrinsic agonistic effect, thereby corroborating the PAM mechanism of these compounds and ruling out the possibility that they behave as agonists, promiscuous allosteric agonists, or ago-allosteric modulators.

The data from the functional assays suggest that the mechanism behind the activity of conjugates 1 and 2 and MIF-1 is the same. The acceptance of a bulky adamantane scaffold at the C-terminal position of MIF-1 neuropeptide adds insightful information to the discussion about MIF-1 pharmacology since the C-terminal primary amide of MIF-1 is considered a key pharmacophore.65 However, earlier studies of our research group have demonstrated that this is not a requisite for PAM activity.20,21,23,47

Interestingly, the replacement of the primary amide by a secondary lipophilic amide in conjugates 1 and 2 resulted in enhanced PAM activity (at 0.01 nM) in comparison with the parent neuropeptide, which exhibited PAM activity only at higher concentrations (1 nM). However, considering conjugates 1 and 2, the presence of the tert-butyl carbamate at the N-terminal position of conjugate 2 did not produce a statistical difference in the PAM potency (p > 0.05, t-test). The potent PAM activity of these conjugates suggests that the introduction of the Am scaffold might interact with a hydrophobic pocket at the allosteric binding site. However, it is important to note that functional assays do not provide information about the binding site(s), so the possibility of these conjugates exploring different allosteric binding sites at the D2R cannot be ruled out.

Cytotoxicity Assays in Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells

The cytotoxicity evaluation of conjugates 1 and 2 was performed in the human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line. This cell line is widely acknowledged as a suitable in vitro model in PD research since it preserves essential features of human dopaminergic neurons.66 As previously demonstrated in our research group,67 the differentiation process of these cells with retinoic acid (RA) and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) for 6 days improves their dopaminergic phenotype and resistance toward dopaminergic neurotoxins.67 Herein, the neurotoxicity of conjugates 1 and 2 and the parent peptide MIF-1, as well as the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), was determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay, in which dehydrogenases, mainly mitochondrial, reduce MTT into the corresponding formazan.67 All of the tested compounds were solubilized in sterile DMSO, except for 6-OHDA, which was prepared in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) immediately before incubation. The results obtained are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Neurotoxicity of the synthesized compounds was evaluated through the MTT reduction assay in human differentiated SH-SY5Y neuronal cells. Cells were incubated for 48 h with 1, 2, MIF-1 (200 μM), DMSO (0.5% final well concentration), and 6-OHDA at 125 μM. Data are expressed as a percentage of the control and are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The results were obtained from 14 to 16 wells and 4 independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by the Tukey’s post hoc test (ns, not significant, *p < 0.05, and ****p < 0.0001 vs control).

In this assay, using 6-OHDA as a positive control for cytotoxicity (125 μM), a pronounced neurotoxicity was observed in the MTT reduction assay (58.27 ± 11.53%, p < 0.0001) after a 48 h period of incubation. In contrast, MIF-1 (94.09 ± 5.75%, p < 0.05) and conjugate 2 (89.73 ± 4.95%, p < 0.0001) exhibited low but meaningful toxicity at 200 μM, while compound 1 did not cause a significant cytotoxic effect at this concentration. Considering the potent PAM activity at subnanomolar concentration, these results indicate that both conjugates 1 and 2 display favorable cytotoxic profiles on differentiated SH-S5Y5 cells.

In conclusion, two bioconjugates of MIF-1 with Am were designed and synthesized by stapling Am at the C-terminal of the neuropeptide through a peptide bond using a C-to-N synthesis strategy. In this study, we demonstrate that Am is an adequate adamantane-based add-on for bioconjugation with MIF-1 with enhanced overall lipophilicity and PAM activity at subnanomolar concentration. None of the bioconjugates exhibited agonistic activity at the D2R, thereby suggesting a PAM mechanism similar to that of MIF-1.

Moreover, the functionalization of the MIF-1 neuropeptide with Am shows that the C-terminal primary amide, deemed as the pharmacophore of MIF-1, is not essential for the PAM activity. Interestingly, its replacement with a hydrophobic secondary amide resulted in a 3.3–4.9-fold increase in DA potency at 0.01 nM, while the parent neuropeptide was found inactive under these conditions. The results might suggest that bulky hydrophobic moieties can be well tolerated at the binding allosteric site at the D2R.

Altogether, the potent PAM potency of 1 and 2 and their favorable neurotoxicity profiles indicate a safe therapeutical window and support the progression of this project by exploring the bioconjugation of MIF-1 with adamantane-based scaffolds as a chemical strategy to leverage the PAM activity and lipophilicity toward a potential viable application in PD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mariana Andrade and Sílvia Maia from Centro de Materiais da Universidade do Porto for their technical assistance with the NMR and HRMS experiments, respectively.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- Am

amantadine

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- CNS

central nervous system

- COSY

correlated spectroscopy

- D2R

dopamine D2 receptors

- DA

dopamine

- DEPT-135

distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer 135

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EC50

half-maximal effective concentration

- Emax

maximal effect

- ESI-HRMS

electrospray ionization-high-resolution mass spectrometry

- Et3N

triethylamine

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- HTRF

homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence

- MIF-1

melanocyte-stimulating hormone release-inhibiting factor-1

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- MSH

melanocyte-stimulating hormone

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PAINS

pan-assay interference compounds

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- RA

retinoic acid

- SH-SY5Y

thrice-subcloned cell line derived from the SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell line

- TBTU

2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00264.

Full experimental details, copies of 1D (1H, 13C{1H}, DEPT-135) and 2D (COSY and HSQC) NMR and HRMS spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

I.E.S.-D. conceived and designed the experiments; I.E.S.-D., S.C.S.-R., X.C.C., H.F.C.-A., B.L.P.-L., and D.M. performed the organic chemistry experiments; I.E.S.-D., S.C.S.-R., and L.C. performed the physicochemical characterization; J.B. and M.I.L. performed the pharmacological assays; S.C.S.-R. and V.M.C. performed the toxicological assays; I.E.S.-D., X.G.-M., and J.E.R.-B. analyzed the data; I.E.S.-D. wrote the paper. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work received financial support from PT national funds (FCT/MCTES, Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia and Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior) through project 2022.01175.PTDC. I.E.S.-D. thanks FCT for funding through the Individual Call to Scientific Employment Stimulus (ref: 2020.02311.CEECIND/CP1596/CT0004) and for funding through the research grant 2022.01175.PTDC. V.M.C. acknowledges FCT for her grant (SFRH/BPD/110001/2015) under the Norma Transitória – DL57/2016/CP1334/CT0006. L.C. thanks the FCT for the research contract DL57/2016/CP1334/CT0008. S.C.S.-R., B.L.P.-L., and D.M. thank the Ph.D. grants SFRH/BD/147463/2019, 2022.14060.BD, and UI/BD/153613/2022, respectively. X.C.C. and H.F.C.-A. thank FCT for the research grants through the project 2022.01175.PTDC. FCT is also acknowledged for supporting LAQV-REQUIMTE (UIDB/50006/2020), UCIBIO-REQUIMTE (UIDB/04378/2020), and i4HB (LA/P/0140/2020) research units. X.G.-M. thanks Xunta de Galicia for financial funding with reference GPC2020/GI1597.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was originally published ASAP on November 14, 2023, with an error in the TOC/Abstract graphic. The revised version was reposted on November 15, 2023.

Supplementary Material

References

- Celis M. E.; Taleisnik S.; Walter R. Regulation of formation and proposed structure of the factor inhibiting the release of melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1971, 68 (7), 1428–1433. 10.1073/pnas.68.7.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scimonelli T.; Celis M. E. Inhibition by l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide (PLG) of alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone release from hypothalamic slices. Peptides 1982, 3 (6), 885–889. 10.1016/0196-9781(82)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma V.; Mann A.; Costain W.; Pontoriero G.; Castellano J. M.; Skoblenick K.; Gupta S. K.; Pristupa Z.; Niznik H. B.; Johnson R. L.; Nair V. D.; Mishra R. K. Modulation of agonist binding to human dopamine receptor subtypes by l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide and a peptidomimetic analog. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 315 (3), 1228–1236. 10.1124/jpet.105.091256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwanth S.; Mishra R. K.; Johnson R. L. Development of peptidomimetic ligands of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 as allosteric modulators of the dopamine D2 receptor. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 204–214. 10.3762/bjoc.9.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava L. K.; Bajwa S. B.; Johnson R. L.; Mishra R. K. Interaction of l-prolyl-l-leucyl glycinamide with dopamine D2 receptor: Evidence for modulation of agonist affinity states in bovine striatal membranes. J. Neurochem. 1988, 50 (3), 960–968. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann A.; Verma V.; Basu D.; Skoblenick K. J.; Beyaert M. G. R.; Fisher A.; Thomas N.; Johnson R. L.; Mishra R. K. Specific binding of photoaffinity-labeling peptidomimetics of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 to the dopamine D2L receptor: Evidence for the allosteric modulation of the dopamine receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 641 (2), 96–101. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R. K.; Makman M. H.; Costain W. J.; Nair V. D.; Johnson R. L. Modulation of agonist stimulated adenylyl cyclase and GTPase activity by l-Pro-l-Leu-glycinamide and its peptidomimetic analogue in rat striatal membranes. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 269 (1), 21–24. 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.; Cheng Z.; Piao J.; Cui R.; Li B. Dopamine receptors: is it possible to become a therapeutic target for depression?. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 947785. 10.3389/fphar.2022.947785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeraully T.; Tan E.-K. Linking restless legs syndrome with Parkinson’s disease: clinical, imaging and genetic evidence. Transl. Neurodegener. 2012, 1 (1), 6. 10.1186/2047-9158-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong M. J.; Okun M. S. Diagnosis and treatment of parkinson disease: A review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323 (6), 548–560. 10.1001/jama.2019.22360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks W. A.; Kastin A. J. Opposite direction of transport across the blood-brain barrier for Tyr-MIF-1 and MIF-1: Comparison with morphine. Peptides 1994, 15 (1), 23–29. 10.1016/0196-9781(94)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau A.; Roy M.; Kastin A. J. Double-blind evaluation of oral l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycine amide in Parkinson’s disease. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1976, 114 (2), 120–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P.-A.; Schneider E.; Jacobi P.; Maxion H. Effect of Melanocyte-stimulating hormone-release inhibiting factor (MIF) in Parkinson’s syndrome. Eur. Neurol. 1974, 12 (5–6), 360–368. 10.1159/000114633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau A. Potentiation of levodopa effect by intravenous l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycine amide in man. Lancet 1975, 306 (7937), 683–684. 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastin A. J.; Barbeau A. Preliminary clinical studies with l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycine amide in Parkinson’s disease. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1972, 107 (11), 1079–1081. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W.; Kastin A. J. From MIF-1 to endomorphin: The Tyr-MIF-1 family of peptides. Peptides 2007, 28 (12), 2411–2434. 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding T. W.; Kastin A. J.; Gonzalez-Barcena D.; Coy D. H.; Hirotsu Y.; Ruelas J.; Schally A. V. The disappearance, excretion, and metabolism of tritiated prolyl-leucyl-glycinamide in man. Neuroendocrinology 1974, 16 (2), 119–126. 10.1159/000122558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensing R. H.; Kastin A. J.; Larsons P. F.; Bishop G. A. Melanocyte-stimulating-hormone release-inhibiting factor-I and tardive dyskinesia. Dis. Nerv. Syst. 1977, 38 (4), 303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira da Costa J.; Caamaño O.; Fernández F.; García-Mera X.; Sampaio-Dias I. E.; Brea J. M.; Cadavid M. I. Synthesis and allosteric modulation of the dopamine receptor by peptide analogs of l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide (PLG) modified in the l-proline or l-proline and l-leucine scaffolds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 69, 146–158. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio-Dias I. E.; Sousa C. A. D.; García-Mera X.; Ferreira da Costa J.; Caamaño O.; Rodríguez-Borges J. E. Novel l-prolyl-l-leucylglycinamide (PLG) tripeptidomimetics based on a 2-azanorbornane scaffold as positive allosteric modulators of the D2R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14 (47), 11065–11069. 10.1039/C6OB02248K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio-Dias I. E.; Silva-Reis S. C.; García-Mera X.; Brea J.; Loza M. I.; Alves C. S.; Algarra M.; Rodríguez-Borges J. E. Synthesis, pharmacological, and biological evaluation of MIF-1 picolinoyl peptidomimetics as positive allosteric modulators of D2R. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10 (8), 3690–3702. 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio-Dias I. E.; Rodríguez-Borges J. E.; Yáñez-Pérez V.; Arrasate S.; Llorente J.; Brea J. M.; Bediaga H.; Viña D.; Loza M. I.; Caamaño O.; García-Mera X.; González-Díaz H. Synthesis, pharmacological, and biological evaluation of 2-furoyl-based MIF-1 peptidomimetics and the development of a general-purpose model for allosteric modulators (ALLOPTML). ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12 (1), 203–215. 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio-Dias I. E.; Reis-Mendes A.; Costa V. M.; García-Mera X.; Brea J.; Loza M. I.; Pires-Lima B. L.; Alcoholado C.; Algarra M.; Rodríguez-Borges J. E. Discovery of new potent positive allosteric modulators of dopamine D2 receptors: Insights into the bioisosteric replacement of proline to 3-furoic acid in the Melanostatin neuropeptide. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64 (9), 6209–6220. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio-Dias I. E.; Silva-Reis S. C.; Pires-Lima B. L.; Correia X. C.; Costa-Almeida H. F. A convenient on-site oxidation strategy for the N-hydroxylation of Melanostatin neuropeptide using Cope elimination. Synthesis 2022, 54 (8), 2031–2036. 10.1055/a-1695-1095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Elst P.; Elseviers M.; De Cock E.; Van Marsenille M.; Tourwé D.; Van Binst G. Synthesis and conformational study of two l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide analogues with a reduced peptide bond. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1986, 27 (6), 633–642. 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1986.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. L.; Rajakumar G.; Yu K. L.; Mishra R. K. Synthesis of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 analogues modified at the prolyl residue and evaluation of their effects on the receptor binding activity of the central dopamine receptor agonist, ADTN. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29 (10), 2104–2107. 10.1021/jm00160a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar G.; Naas F.; Johnson R. L.; Chiu S.; Yu K. L.; Mishra R. K. Down-regulation of haloperidol-induced striatal dopamine receptor supersensitivity by active analogues of l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide (PLG). Peptides 1987, 8 (5), 855–861. 10.1016/0196-9781(87)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baures P. W.; Pradhan A.; Ojala W. H.; Gleason W. B.; Mishra R. K.; Johnson R. L. Synthesis and dopamine receptor modulating activity of unsubstituted and substituted triproline analogues of l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide (PLG). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9 (16), 2349–2352. 10.1016/S0960-894X(99)00386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. C.; Pradhan A.; Venkatraman S.; Ojala W. H.; Gleason W. B.; Mishra R. K.; Johnson R. L. Synthesis and dopamine receptor modulating activity of novel peptidomimetics of l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide featuring α,α-disubstituted amino acids. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42 (8), 1441–1447. 10.1021/jm980656r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C.; Ohnmacht U.; Niger M.; Gmeiner P. Beta-analogs of PLG (l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide): ex-chiral pool syntheses and dopamine D2 receptor modulating effects. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8 (20), 2885–2890. 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomo C.; Aizpurua J. M.; Benito A.; Miranda J. I.; Fratila R. M.; Matute C.; Domercq M.; Gago F.; Martin-Santamaria S.; Linden A. Development of a new family of conformationally restricted peptides as potent nucleators of β-turns. Design, synthesis, structure, and biological evaluation of a β-lactam peptide analogue of Melanostatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (52), 16243–16260. 10.1021/ja038180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalauzka R.; Dzimbova T.; Bocheva A.; Pajpanova T. MIF-1 and Tyr-MIF-1 analogues containing unnatural amino acids: synthesis, biological activity and docking studies. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24 (6), 2393–2405. 10.1007/s00044-014-1302-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzon K.; Tobias D. J.; Holmes R. E.; Rathbun R. E.; Kattau R. W. The adamantyl group in medicinal agents. IV. Sedative action of 3,5,7-trimethyladamantane-1-carboxamide and related agents. J. Med. Chem. 1967, 10 (4), 603–606. 10.1021/jm00316a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift P. A.; Stagnito M. L.; Mullen G. B.; Palmer G. C.; Georgiev V. S. 2-(Substituted amino)-2-[2′-hydroxy-2′-alkyl(or aryl)]ethyltricyclo-[3.3.1.13,7]decane derivatives: a novel class of anti-hypoxia agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 23 (5), 465–471. 10.1016/0223-5234(88)90144-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanka L.; Iqbal K.; Schreiner P. R. The lipophilic bullet hits the targets: Medicinal chemistry of adamantane derivatives. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113 (5), 3516–3604. 10.1021/cr100264t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommaert A. G. S.; Weng J. H.; Dorville A.; McCort I.; Ducos B.; Durieux C.; Roques B. P. Cholecystokinin peptidomimetics as selective CCK-B antagonists: Design, synthesis, and in vitro and in vivo biochemical properties. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36 (20), 2868–2877. 10.1021/jm00072a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellier B.; McCort-Tranchepain I.; Ducos B.; Danascimento S.; Meudal H.; Noble F.; Garbay C.; Roques B. P. Synthesis and biological properties of new constrained CCK-B antagonists: Discrimination of two affinity states of the CCK-B receptor on transfected CHO cells. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40 (24), 3947–3956. 10.1021/jm970439a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R. S.; England A. C. Jr; Poskanzer D. C.; Young R. R. Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1969, 208 (7), 1168–1170. 10.1001/jama.1969.03160070046011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes J. D.; Calver D. M.; Zilkha K. J.; Knill-Jonbs R. P. Controlled trial of amantadine hydrochloride in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 1970, 295 (7641), 259–262. 10.1016/S0140-6736(70)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos V.; Heathfield K.; Stone P.; Allen F. A. D. Use of amantadine in Parkinson’s disease. Results of a double-blind trial. Br. Med. J. 1970, 4 (5726), 24–26. 10.1136/bmj.4.5726.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieschi C.; Nardini M.; Casacchia M.; Tedone M. E.; Robotti E. Amantadine for Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 1970, 295 (7653), 945–946. 10.1016/S0140-6736(70)91065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R. S.; Poskanzer D. C.; England A. C. Jr; Young R. R. Amantadine in Parkinson’s disease: Review of more than two years’ experience. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1972, 222 (7), 792–795. 10.1001/jama.222.7.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.-C.; Wu T.-L.; Lin F.-J.; Tai C.-H.; Lin C.-H.; Wu R.-M. Amantadine treatment and delayed onset of levodopa-induced dyskinesia in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29 (4), 1044–1055. 10.1111/ene.15234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K. M.; Goetz C. G.; Carroll V. S.; Tanner C. M.; Klawans H. L. Amantadine and motor fluctuations in chronic Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1987, 10 (6), 522–526. 10.1097/00002826-198712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörg J.; Pröfrock A. Wirksamkeit und verträglichkeit der Parkinson-behandlung mit amantadinsulfat. Nervenheilkunde 1995, 14 (2), 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rascol O.; Fabbri M.; Poewe W. Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20 (12), 1048–1056. 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira da Costa J.; Silva D.; Caamaño O.; Brea J. M.; Loza M. I.; Munteanu C. R.; Pazos A.; García-Mera X.; González-Díaz H. Perturbation theory/machine learning model of ChEMBL data for dopamine targets: Docking, synthesis, and assay of new l-prolyl-l-leucyl-glycinamide peptidomimetics. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9 (11), 2572–2587. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Brindisi M. Organic carbamates in drug design and medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58 (7), 2895–2940. 10.1021/jm501371s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro M.; Sampaio-Dias I. E.; Mateus N.; de Freitas V.; Cruz L. Preparation of 10-(hexylcarbamoyl)pyranomalvidin-3-glucoside from 10-carboxypyranomalvidin-3-glucoside using carbodiimide chemistry. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133429. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnott J. A.; Planey S. L. The influence of lipophilicity in drug discovery and design. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2012, 7 (10), 863–875. 10.1517/17460441.2012.714363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A.; Michielin O.; Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 42717. 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Open-source cheminformatics. http://zinc15.docking.org/patterns/home (accessed 2023-06-12).

- Chiu S.; Paulose C. S.; Mishra R. K. Effect of L-prolyl-L-leucyl-glycinamide (PLG) on neuroleptic-induced catalepsy and dopamine/neuroleptic receptor bindings. Peptides 1981, 2 (1), 105–111. 10.1016/S0196-9781(81)80019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. L.; Rajakumar G.; Mishra R. K. Dopamine receptor modulation by Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 analogs possessing cyclic amino acid residues at the C-terminal position. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29 (10), 2100–2104. 10.1021/jm00160a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan U.; Mishra R. K.; Johnson R. L. Synthesis and dopamine receptor modulating activity of lactam conformationally constrained analogs of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36 (2), 256–263. 10.1021/jm00054a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K. L.; Rajakumar G.; Srivastava L. K.; Mishra R. K.; Johnson R. L. Dopamine receptor modulation by conformationally constrained analogs of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31 (7), 1430–1436. 10.1021/jm00402a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitton S.; Del Tredici A. L.; Mohell N.; Vollinga R. C.; Boström D.; Kihlberg J.; Luthman K. Design, synthesis and evaluation of a PLG tripeptidomimetic based on a pyridine scaffold. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47 (26), 6595–6602. 10.1021/jm049484q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitton S.; Del Tredici A. L.; Saxin M.; Stenström T.; Kihlberg J.; Luthman K. Synthesis and evaluation of novel pyridine based PLG tripeptidomimetics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6 (9), 1647–1654. 10.1039/b718058f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastin A. J.; Pan W. Concepts for biologically active peptides. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16 (30), 3390–3400. 10.2174/138161210793563491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R. K.; Marcotte E. R.; Chugh A.; Barlas C.; Whan D.; Johnson R. L. Modulation of dopamine receptor agonist-induced rotational behavior in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats by a peptidomimetic analogue of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 (PLG). Peptides 1997, 18 (8), 1209–1215. 10.1016/S0196-9781(97)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costain W. J.; Buckley A. T.; Evans M. C.; Mishra R. K.; Johnson R. L. Modulatory effects of PLG and its peptidomimetics on haloperidol-induced catalepsy in rats. Peptides 1999, 20 (6), 761–767. 10.1016/S0196-9781(99)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkman S.; Sievertsson H. On the optimal dosage of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 (MIF) in neuropharmacological tests and clinical use. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1977, 298 (2), 79–81. 10.1007/BF00508614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensing R. H.; Kastin A. J.; Wurzlow G. F.; Michell G. F.; Mebane A. H. Improvement in major depression after low subcutaneous doses of MIF-1. J. Affective Disord. 1994, 31 (4), 227–233. 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensing R. H.; Kastin A. J. Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone-Release Inhibiting Hormone as an Antidepressant: A Pilot Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1974, 30 (1), 63–65. 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760070047007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mycroft F. J.; Bhargava H. N.; Wei E. T. Pharmacological activities of the MIF-1 analogues Pro-Leu-Gly, Tyr-Pro-Leu-Gly and pareptide. Peptides 1987, 8 (6), 1051–1055. 10.1016/0196-9781(87)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xicoy H.; Wieringa B.; Martens G. J. M. The SH-SY5Y cell line in Parkinson’s disease research: A systematic review. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12 (1), 10. 10.1186/s13024-017-0149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira P. S.; Nogueira T. B.; Costa V. M.; Branco P. S.; Ferreira L. M.; Fernandes E.; Bastos M. L.; Meisel A.; Carvalho F.; Capela J. P. Neurotoxicity of ″ecstasy″ and its metabolites in human dopaminergic differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 216 (2–3), 159–170. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.