Abstract

Background:

Shigella has been associated with community-wide outbreaks in urban settings. We analyzed a sustained shigellosis outbreak in Seattle, Washington, USA, to understand its origins and mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), define ongoing transmission patterns, and optimize strategies for treatment and infection control.

Methods:

All Shigella isolates identified at the clinical laboratories at Harborview Medical Center and University of Washington Medical Center from 2017–2022 were characterized by species identification, phenotypic susceptibility testing, and whole genome sequencing. Demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes of the patients were retrospectively examined.

Findings:

One-hundred seventy-one cases of shigellosis were included. Seventy-eight (45.6%) patients were men who have sex with men (MSM), and 88 (51.5%) were persons experiencing homelessness (PEH). Although nearly half of isolates (84; 50.6%) were multidrug-resistant, 100 out of 143 (69.9%) patients with data on antimicrobial therapy received appropriate empiric therapy. Phylogenomic analysis identified sequential outbreaks of multiple distinct lineages of S. flexneri and S. sonnei. Discrete clonal lineages (10 in S. flexneri and 9 in S. sonnei) and resistance traits were responsible for infection in different at-risk populations, enabling development of effective guidelines for empiric treatment. The most prevalent lineage in Seattle was likely introduced to Washington State via international travel, with subsequent domestic transmission between at-risk groups.

Interpretation:

An outbreak in Seattle was driven by parallel emergence of multidrug-resistant strains involving international transmission networks and domestic transmission between at-risk populations. Genomic analysis elucidated not only outbreak origin, but directed optimal approaches to testing, treatment, and public health response.

Keywords: Shigella, shigellosis, antimicrobial resistance, rapid diagnostic testing, whole genome sequencing, gastroenteritis, diarrhea, men who have sex with men (MSM), persons experiencing homelessness (PEH)

INTRODUCTION

Shigella spp. are highly transmissible enteric pathogens that produce symptoms ranging from mild diarrhea to severe dysentery and fever.1 Shigella is spread by a fecal-oral route and may exhibit prolonged shedding after symptom resolution. In high-income countries, men who have sex with men (MSM), travelers to endemic countries, and children in daycare settings comprise high-risk groups, whereas individuals with inadequate access to hygiene and sanitation are at increased risk for acquisition from contaminated food or water in both high- and low-income countries.1 Sustained shigellosis outbreaks in urban settings pose a substantial public health challenge,2,3 and multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant Shigella strains are a growing concern worldwide.4,5

Shigellosis is frequently self-limited in immunocompetent patients, but antibiotics are routinely used to treat symptoms and to reduce bacterial shedding and community transmission.1 As some cases of infection are culture-negative,6 and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of culture-positive cases can take several days, most antibiotic treatment is empiric.

Since 2017, a sustained increase in shigellosis has been reported in Seattle and King County, Washington State, USA with a marked increase observed after 2020,7 particularly among persons experiencing homelessness (PEH). This study was undertaken to better understand the community transmission of Shigella and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in our population. All Shigella isolates from medical facilities serviced by the clinical laboratories at Harborview Medical Center (HMC) and University of Washington Medical Center (UWMC) were subjected to phenotypic characterization and whole genome sequencing (WGS). This information was correlated with demographic characteristics of patients and used to optimize strategies for treatment and infection control based on individual risk factors and local susceptibility patterns.

METHODS

Study design and setting

Shigella was detected from stool using the BioFire® FilmArray® Gastrointestinal (GI) multiplex PCR panel (bioMérieux, Salt Lake City, UT) in adult patients with diarrhea who visited HMC or UWMC-affiliated outpatient clinics, emergency departments, or hospitals between May 2017 and February 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of the University of Washington with a waiver for informed consent.

Microbiological testing

In accordance with routine laboratory procedures, stool specimens positive for Shigella/Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) by multiplex PCR were cultured. Isolates were obtained by reflexive subculture to HardyCHROM™ SS NoPRO agar (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Clara, CA) and cryopreserved. AST was performed by broth microdilution (Trek Sensititre, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), and ceftriaxone. Susceptibility to azithromycin was measured by ETEST (bioMérieux, March-l’Étoile, France). CLSI breakpoints were used for the interpretation of AST results (Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, M100, 30th Edition, January 2020). In parallel, in accordance with state law, stools positive for Shigella/EIEC by multiplex PCR were sent to the Public Health Laboratory (PHL) for species identification, serotyping, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Whole genome sequencing and molecular epidemiology

WGS and single-nucleotide variant calling for each isolate were conducted as described in Supplemental Methods (“Sequencing Methods”). Plasmid detection utilized PlasmidSeeker v1.38 employing a custom library incorporating additional plasmids relevant to Shigella spp. Separate core genome alignments for S. flexneri and S. sonnei were created using Roary v3.13.09 and used to calculate pairwise distance matrices. Time-measured phylogenies were inferred from these core genome alignments using BEAST v1.10.410 (Supplemental Methods, “Genomic Analysis”). Clonal groups were circumscribed as described in Supplemental Methods (“Classification of Related Isolates by Numbered Lineage”).

Focused analyses of specific lineages were performed in conjunction with publicly available genome sequences. Published sequences with available clinical or geographic metadata were prioritized for review based on genomic sequence similarity by ANIb, presence of similar plasmid complements, or inclusion in a common NCBI Pathogen Detection SNP cluster. Phylogenomic analysis of WGS data from potentially related references in conjunction with study isolates was performed using BEAST as above on a per-species basis. Sequence data from this project have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA791692, PRJNA862511).

Analysis of antimicrobial resistance determinants

Identification of antimicrobial resistance genes and mutations was performed using AMRFinderPlus v3.10.30.11 Loci associated with resistance to tested agents in Shigella spp. were cataloged across all isolates. A previous study showed that the correlation between antibiotic resistance phenotypes and genotypes is very high in S. sonnei, except for streptomycin.12 We therefore performed hierarchical clustering of AMRFinderPlus, PlasmidSeeker, AST, and clinical characteristics using h-clust and pheatmap13 to prioritize genotypes most closely correlated with clinical phenotypes of interest in an unbiased fashion.

Chart review and statistical analysis

Medical records were reviewed to record relevant clinical characteristics (Supplemental Table 1). Clinical characteristics and outcomes were summarized in Table 1. Multidrug resistance was defined as resistance to at least three antibiotic classes,14 and appropriateness of therapy was based on AST results. Univariable comparisons were performed to identify differences in characteristics among the compared groups. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical variables. For comparison of continuous variables, t-test or Mann-Whitney test (for normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively) were used. Dependent variables were hospitalization and inappropriate therapy, while independent variables were MSM or PEH status, infection with S. flexneri or S. sonnei, MDR infection, dysentery (bloody diarrhea), HIV infection, and age. P-value ≤0.05 indicated statistical significance. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated for hospitalization and appropriateness of therapy. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of patients with shigellosis, n (%)

| Number of patients | 171 |

| Sex, male | 148 (86.5) |

| Median age, IQR (y) | 41, 21 |

| MSM | 78 (45.6) |

| PEH | 88 (51.5) |

| Sex male | 74 (84.1) |

| Travel-related shigellosis | 10 (5.8) |

| Dysentery (bloody diarrhea) | 37 (21.6) |

| HIV | 59 (34.5%) |

| Hospital admission* | 56 (32.7) |

| ICU admission* | 8 (4.7) |

| Shigella spp. | |

| S. flexneri | 112 (65.5) |

| MSM | 55 |

| PEH | 58 |

| S. sonnei | 55 (32.2) |

| MSM | 20 |

| PEH | 30 |

| S. boydii | 1 (0.6) |

| Shigella spp. | 3 (1.8) |

| Resistance | |

| Azithromycin | 88 (51.5) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 61 (35.7) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 81 (47.4) |

| Ceftriaxone | 33 (19.3) |

| MDR** (resistant to at least 3 classes of antibiotics) |

84 (50.6) |

| Prior abx within 3 months | 26 (15.2) |

| Antibiotic therapy | 138 (80.7) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 50 (29.2) |

| Azithromycin | 32 (18.7) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 36 (21.1) |

| Other | 21 (12.3) |

| Appropriate therapy*** | 100 (69.9) |

| Inappropriate therapy | 28 (19.6) |

| Therapy of unknown efficacy | 15 (10.5) |

Abbreviations

IQR: interquartile range; y: years; MSM: men who have sex with men; PEH: people experiencing homelessness; ICU: intensive care unit; MDR: multidrug resistance

Hospital or ICU admission were not attributed to Shigella infection but to the patients’ comorbidities.

Five patients were excluded from this analysis because of unavailable data on all antibiotics tested.

There were 28 patients who were excluded from the analysis on appropriateness of therapy because they were not prescribed antibiotics (n=23) or information about therapy was not clear in the medical record (n=5). In addition, treatment with ciprofloxacin is generally avoided when MIC is 0.12 μg/mL or higher per CDC guidance, but for the purpose of this analysis, treatment with ciprofloxacin was considered appropriate if the MIC was within the susceptible range.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Two hundred and fifty-four patients were diagnosed with Shigella infection in our hospitals during the study period, 179 of which had positive reflexive stool cultures. Eight cases were excluded from analysis because of sample inadequacy, leaving 171 isolate/patient pairs ultimately included in the study (Table 1, Supplemental Table 1). Samples originated from three hospitals and 17 affiliated outpatient clinics.

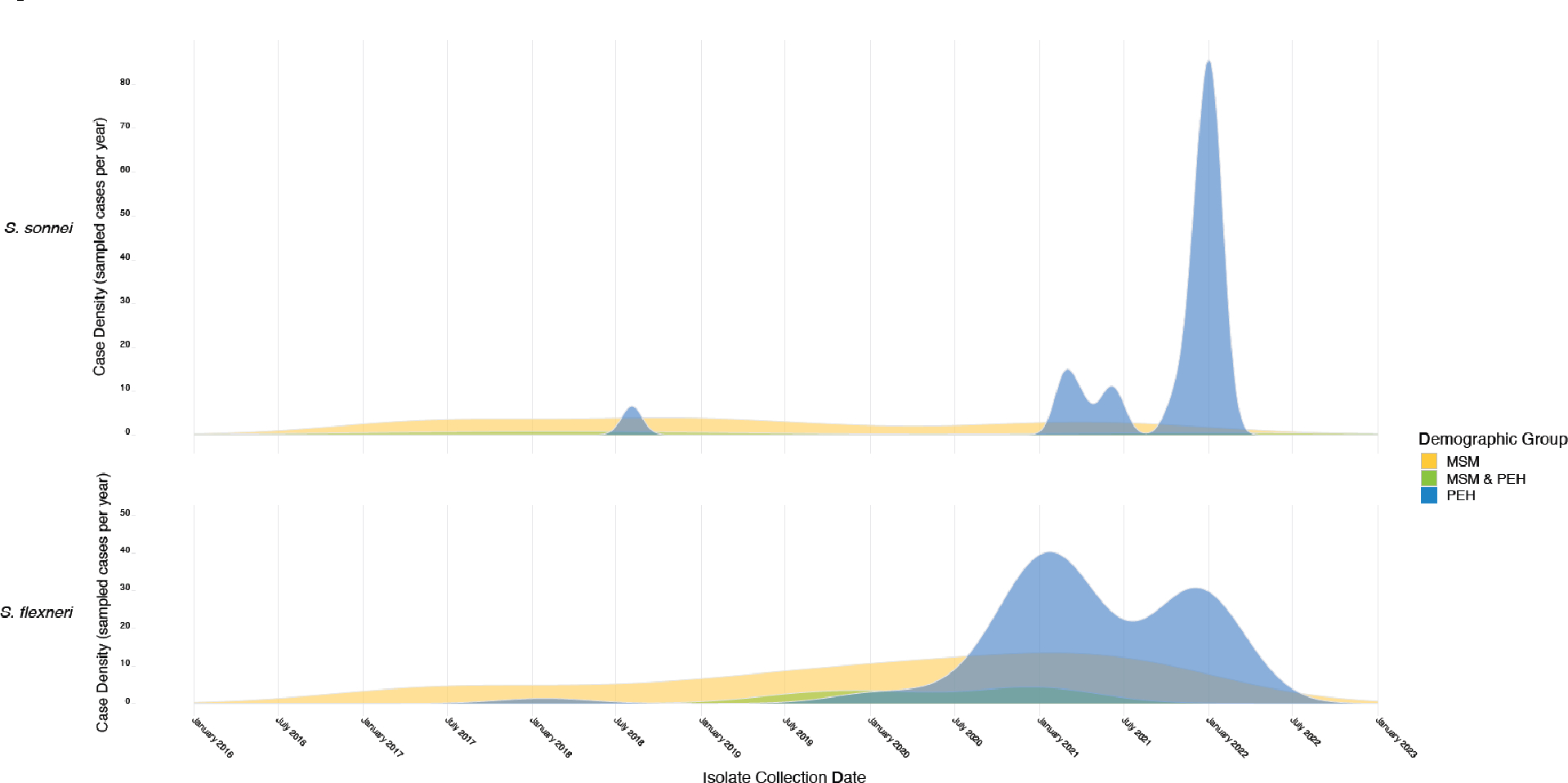

One-hundred forty-eight (86.5%) were males. Eighty-eight (51.5%) were PEH, while 78 (45.6%) identified as MSM. Eleven (6.4%) patients identified as both MSM and PEH. Ten (5.8%) cases of shigellosis were acquired during international travel to countries in Asia, Africa, or South America. S. flexneri (n=112) was the most common species isolated, followed by S. sonnei (n=55), with parallel outbreaks shifting between MSM and PEH populations over the study period (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 1). A single S. boydii isolate originated from a patient who traveled to Somalia. Three other isolates were not identified to species level (reported as Shigella spp.).

Figure 1. Timeline of Shigellosis cases in Seattle, Washington, USA, by demographic group and species.

Vertical axis indicates density of infections sampled in each specified demographic group over time. A parallel timeline showing relative case density normalized by group is presented in Supplemental Figure 1 to better display waves of transmission between at-risk populations, including relatively small but important groups such as such as patients identifying as both MSM and PEH. MSM: men who have sex with men, PEH: persons experiencing homelessness.

Diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and fever were the most common symptoms. Dysentery was documented in 37 patients (21.6%) with similar frequency among MSM (20.3%), PEH (20.5%), and international travelers (20%). The occurrence of dysentery was not statistically significantly different between patients with S. flexneri and those with S. sonnei infections (28/112, 25% vs. 9/55, 16.3%, p=0.27).

Antibiotics (Table 1) were empirically prescribed to 138 patients (80.7%). In hospitalized patients, treatment was transitioned to an oral regimen at the time of discharge. Results of AST are summarized by patient group in Table 2. In total, 84 of the 166 isolates (50.6%) with relevant available data were MDR. Twenty-eight patients were excluded from analysis on appropriateness of therapy because they were not prescribed antibiotics (n=23) or did not have information about therapy in the medical record (n=5). The initially prescribed agent was appropriate in 100 (69.9 %) cases, inappropriate in 28 (19.6%), and indeterminate in 15 (10.5%) (concordance could not be determined in these cases because the prescribed drug was not tested in vitro). Among patients who received inappropriate therapy, ten had symptoms for ≤1 week, six for >1 week, and 12 for an unknown period of time. Patient characteristics (i.e., PEH or MSM status, MDR profile) were also compared in terms of appropriateness of therapy (Supplemental Table 3). Inappropriate therapy was more common among patients with MDR Shigella spp. (20/63, 31.7%% vs. 6/57, 10.5%; OR 3.9, 95% CI: 1.3–13, p=0.007).

Table 2.

Resistance to antibiotics tested per patient group

| Ampicillin | Azithromycin | Ciprofloxacin | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Ceftriaxone | MDR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEH | 88/88 (100) | 39/88 (44.3) | 46/88 (52.3) | 16/88 (18.2) | 27/88 (30.7) | 38/88 (43.2) |

| MSM | 75/78 (96.2) | 55/78 (70.5) | 10/78 (12.8) | 61/78 (78.2) | 5/78 (6.4) | 50/78 (64.1) |

| All patients | 162/171 (94.7) | 88/171 (51.5) | 60/171 (35.1) | 81/171 (47.4) | 33/171 (19.3) | 84/171 (49.1) |

Fifty-six (32.7%) and eight (4.7%) patients were admitted to the hospital ward or ICU, respectively. A small number of patients had already been admitted for other reasons for less than 48 hours at the time Shigella was identified. Univariable analyses for associations between patient characteristics and hospital admission (Supplemental Table 2), revealed that older patients (median 46 years, interquartile range: 21.5 vs. 39 years, interquartile range: 22 years old, p=0.002) and PEH (40/88, 45.5% vs. 16/83, 19.3%; OR 3.46, 95% CI: 1.67–7.44, p<0.001) were more likely to require hospitalization, while MSM patients were less likely to require hospitalization (16/78, 20.5% vs. 40/92, 43.5%; OR 0.33, 95% CI: 0.15–0.69, p=0.002).

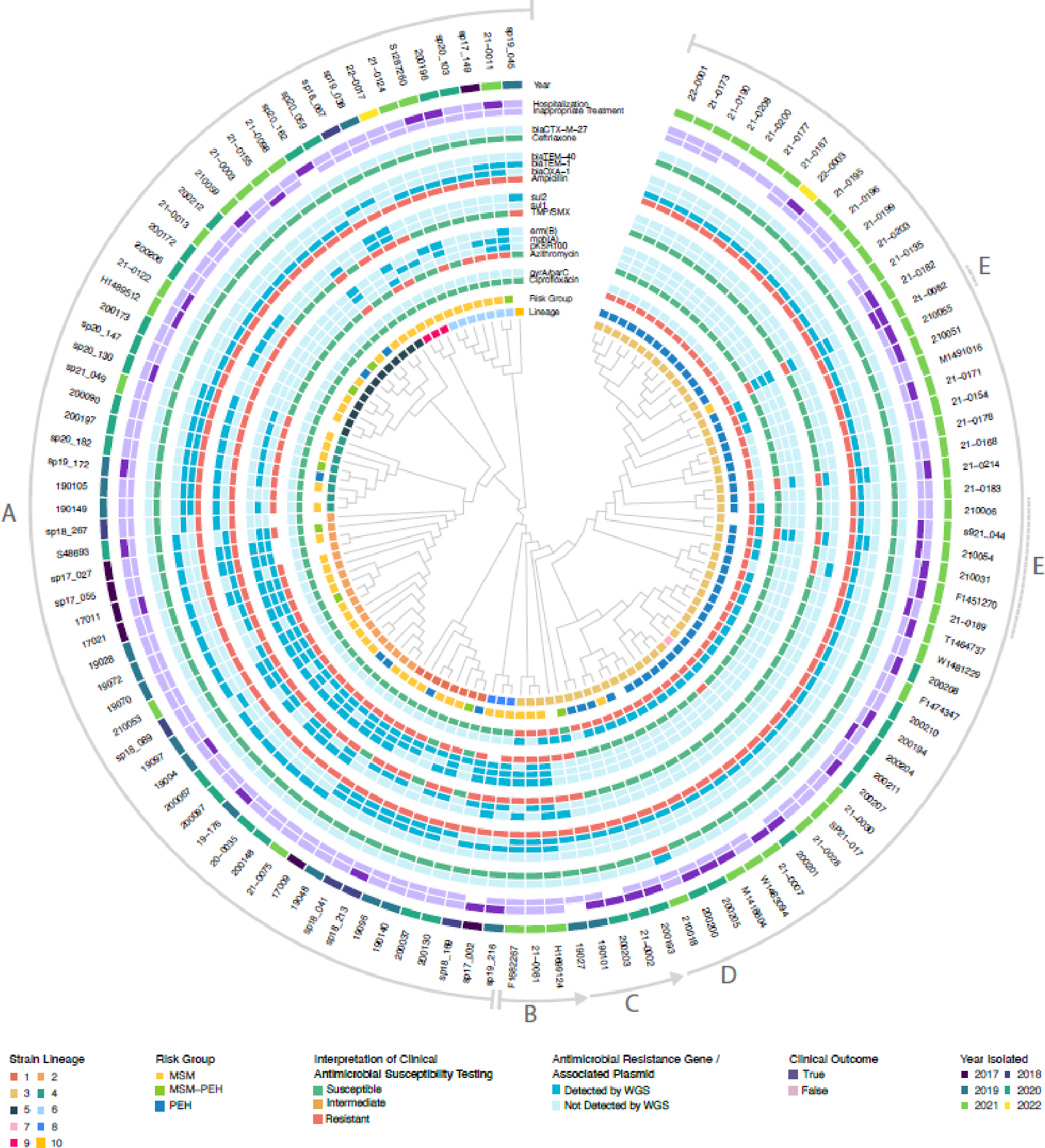

Genomic analysis (Figure 2) of S. flexneri circumscribed 10 phylogenomically related clusters (isolates defined by an empirically derived threshold of <150 genomic variants, see Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Figure 2). S. flexneri infections during the study period were characterized by small, temporally overlapping clusters of genetically distinct lineages preceding a sustained outbreak associated with introduction of a previously unencountered strain (lineage 3) in 2019. For each lineage, isolates with the earliest branch dates occurred in the MSM population and were later observed in PEH.

Figure 2. Cladogram showing molecular epidemiology, resistance, and clinical characteristics of S. flexneri isolates.

Relevant metadata are reported circumferentially, followed by isolate identification labels. Lettered arcs around the periphery indicate specific events during procession of the outbreak: A) Serial introduction of phylogenetically distinct S. flexneri strains into Seattle over several decades. In each clade, lineages most closely related to the ancestral node were isolated from MSM. Lineages vary in accessory AMR gene content but are uniformly ciprofloxacin-susceptible. Sharing of AMR genes among unrelated lineages is common, consistent with horizontal gene transfer. B) Detection of a new ciprofloxacin-resistant strain in MSM. C) A new strain is observed at the demographic interface of the MSM/PEH populations (e.g., 190101) and loses resistance to azithromycin and TMP-SMX at the same juncture. D) Strain spreads rapidly through PEH population. E) Emergence of MDR derivatives through combination of chromosomally mediated ciprofloxacin resistance with plasmid-mediated macrolide/TMP-SMX/ceftriaxone resistance. MDR is associated with inappropriate empiric therapy and hospitalization. MSM: men who have sex with men, PEH: persons experiencing homelessness, TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

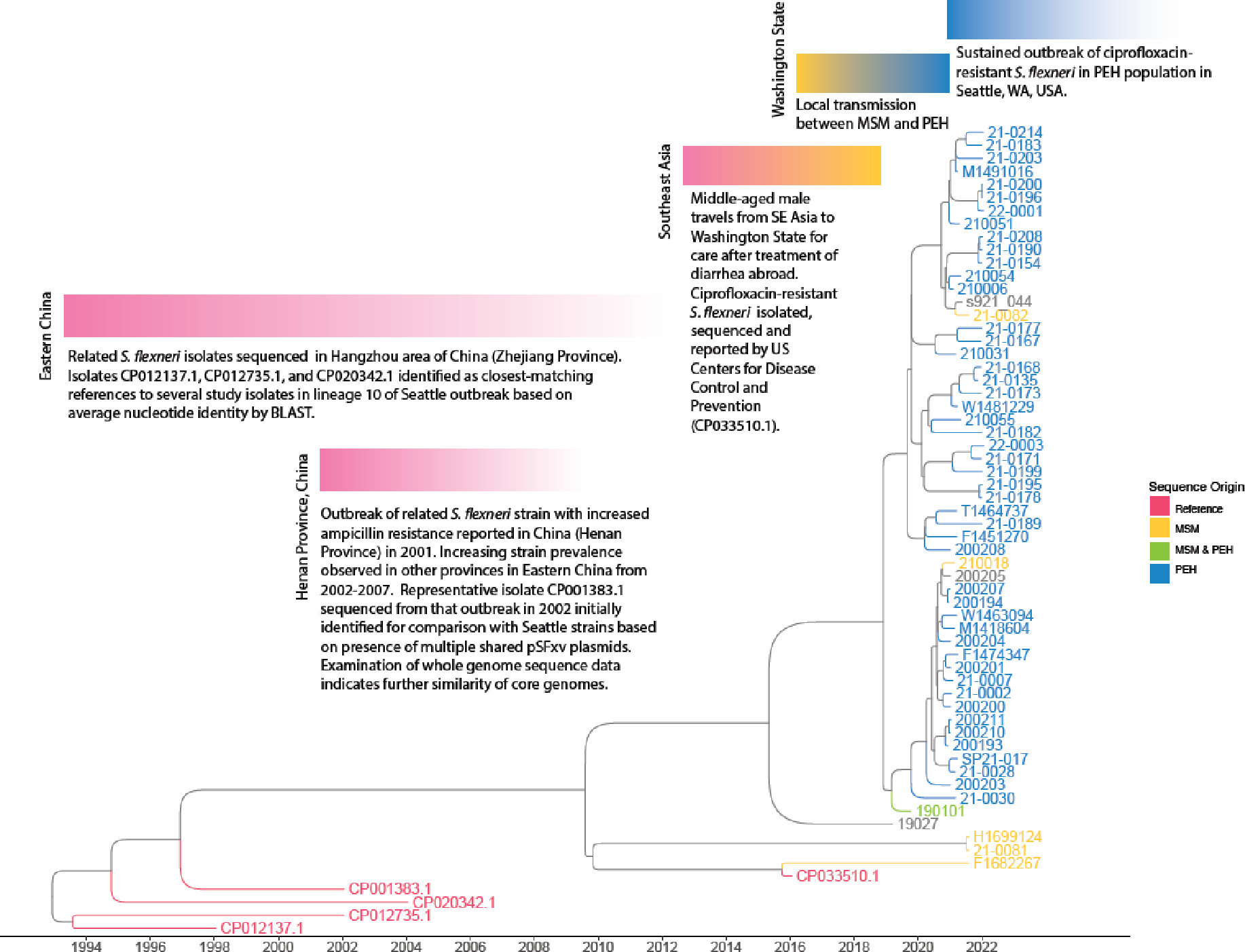

Focused analysis of lineage 3 identified five reference genomes from GenBank having the greatest genomic similarity to multiple isolates from that lineage (Figure 3). Eighty-one isolates in the same NCBI Pathogen Detection SNP Cluster were identified, all derived from recent US CDC PulseNet USA submissions (2021–2022), but none having sufficient geographic or clinical metadata to enable meaningful comparison. The earliest strains in the lineage 3 time-measured phylogeny were derived from clinical isolates from China in the early 2000s, including an MDR outbreak strain in which multiple plasmids found in Seattle were first described.15 The most recently derived reference sequence (CP033510.1) was isolated from a middle-aged male who acquired diarrhea while traveling in Southeast Asia in 2016 and was treated with ciprofloxaxin.16 The patient subsequently traveled to Washington State in the US two to three weeks later, where he was again prescribed ciprofloxacin. Ciprofloxacin-resistant S. flexneri was subsequently isolated, reported to the US CDC, and characterized by WGS.

Figure 3. Annotated timeline of S. flexneri lineage 3 isolates and related references sequences.

Estimated dates of divergence based on time-measured Bayesian analysis of molecular sequences. Phylogenomic and epidemiological links are consistent with international dissemination of this strain from China to Seattle in association with international travel but should not be interpreted to portray case-level transmission events. Tips labeled in grey represent study isolates without demographic risk group information. A simplified version of this tree annotated with 95% highest posterior density intervals is provided as Supplemental Figure 6.

The most important AMR genes detected across our isolates are collectively presented in Supplemental Table 4. Antimicrobial susceptibility phenotypes correlated closely with AMR gene profiles in both S. flexneri (Supplementary Figure 3) and S. sonnei (Supplemental Figure 4). Resistance profiles of individual isolates were generally similar within lineages, but patterns of common accessory AMR gene content across distinct clades is consistent with horizontal gene transfer of plasmid-mediated resistance in both species. All S. flexneri isolates were ampicillin-resistant and correspondingly harbored a range of beta-lactamases including blaOXA and blaTEM genes. Azithromycin resistance correlated with presence of mph(A) and erm(B), carried in most cases by plasmid pKSR100. In the background of numerous dfrA trimethoprim resistance genes, most variation in TMP-SMX susceptibility was explained by the presence of sul1 or sul2 sulfonamide resistance genes. Prior to the introduction of lineage 3, isolates were universally susceptible to ciprofloxacin (Figure 2). Lineage 3 isolates harbored parC (S80I) and gyrA (S83L and D87N) mutations, which may have facilitated its rapid initial spread in a region with previously low rates of ciprofloxacin resistance. The earliest lineage 3 isolate carried sul1/sul2 and mph(A)/erm(B), mediating TMP-SMX and azithromycin resistance, respectively. While these genes were lost during the transition between MSM and PEH groups, other TMP/SMX- and azithromycin-resistant lineages persisted among MSM in Seattle. Ceftriaxone resistance mediated by blaCTX–M–27 was observed in a single lineage 3 case (210018) at the end of the study period, isolated from an MSM patient with no recent international travel.

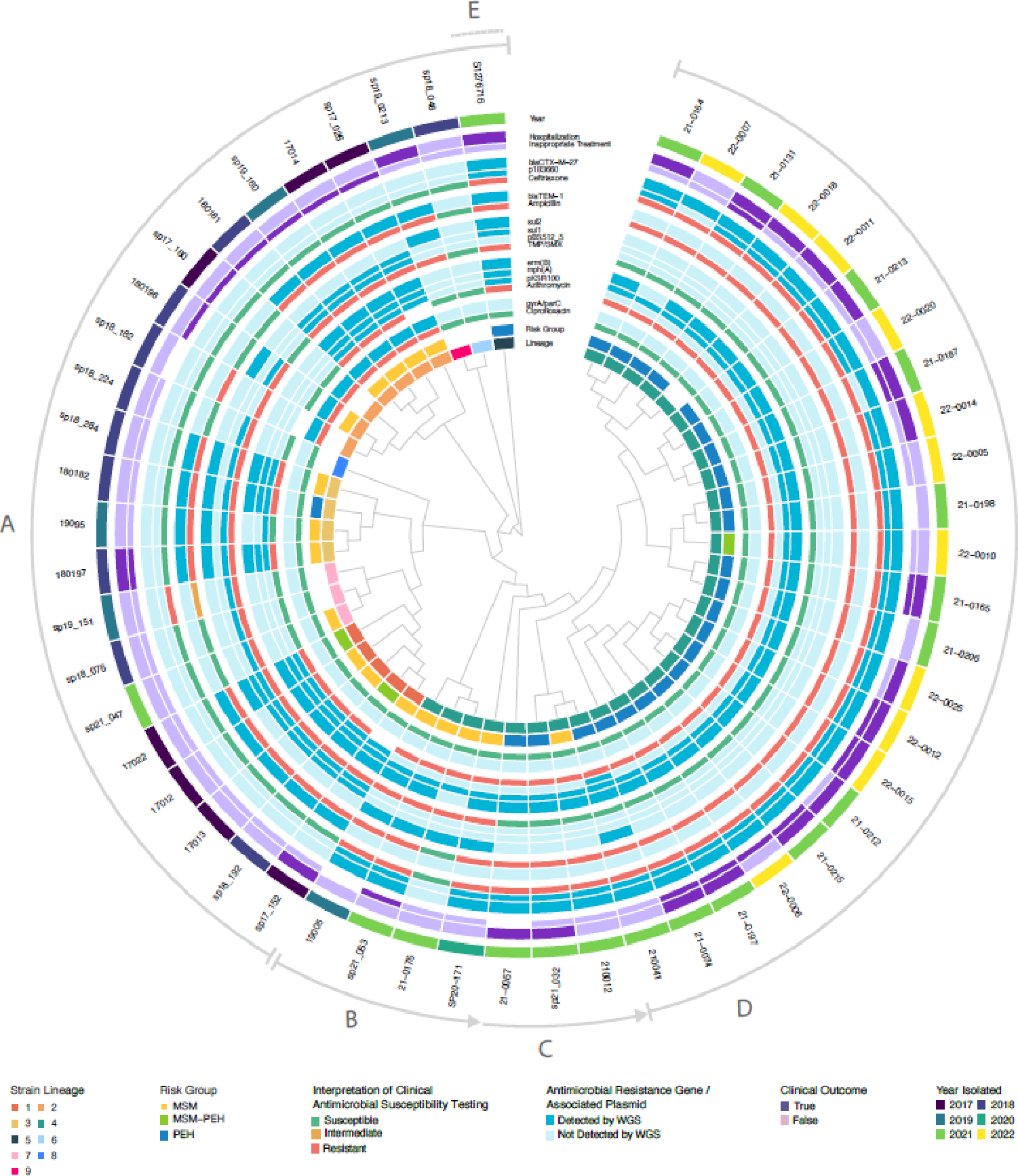

Genomic analysis (Figure 4) of S. sonnei identified nine clusters (isolates distinguished by a derived threshold of <125 single-nucleotide polymorphisms, see Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Figure 5). Global genotype assignments based on recently established nomenclature for S. sonnei are presented in Supplemental Table 5. Lineage 2, associated with the earliest S. sonnei outbreak among MSM in Seattle (2017 to 2019), showed close phylogenetic similarity to isolates from an ongoing, MDR outbreak recently reported among MSM in the UK,2 constituting a recently recognized and internationally emergent clade (global genotype 3.6.1.1).17 Seattle and UK representatives of these lineages were estimated to share a MRCA in early 2019 (95% CI: March 2018-November 2019), with one Seattle isolate (180181) falling within the 10-SNP distance threshold used to define clonality for the UK outbreak.2

Figure 4. Cladogram showing molecular epidemiology, resistance, and clinical characteristics of S. sonnei isolates.

Relevant metadata are reported circumferentially, followed by isolate identification labels. Lettered arcs around the periphery indicate specific events during procession of the outbreak: A) Serial introduction of phylogenetically distinct S. sonnei strains over several years. Sharing of resistance plasmids is common among unrelated strains. B) Detection of a new blaCTX-M-27 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-carrying strain in the MSM population, 2019. C) This new strain spreads between MSM and PEH populations and loses plasmid-mediated resistance to TMP-SMX at this same juncture. Cases have high rates of inappropriate empiric treatment and hospitalization. D) Strain spreads rapidly through PEH population. E) Recent emergence of multidrug-resistant phenotype in unrelated strain (clade 5) with both pKSR100 and p183660 resistance plasmids. MSM: men who have sex with men, PEH: persons experiencing homelessness, TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Lineage 4 (global genotype 3.7.29.1.4.1), responsible for the largest and most recent S. sonnei outbreak in Seattle, was first recovered from MSM in Seattle in 2019 and became dominant among the PEH population during the following two years. Examination of similar references and NCBI Pathogen Detection SNP cluster sequences suggest a general epidemiological link with European travel, evidenced by the observance of similar isolates in Austria, the UK, and Belgium since 2020. The closest matching reference (CP049167.1), also global genotype 3.7.29.1.4.1 and carrying blaCTX-M-27, is an isolate from a middle-aged male patient in Switzerland treated for diarrhea in 2019 (strain #09163633).18

The influence of antimicrobial resistance on the local epidemiology of S. sonnei infection in Seattle bears several similarities to outbreaks reported in the UK2 and Australia,19 in that after a period of decline in infections caused by overlapping lineages with varied resistance phenotypes, a resurgence of monophyletic infections among MSM was observed in 2020 following acquisition of plasmid-borne blaCTX-M-27.

Local treatment guidelines for shigellosis initially recommended empiric therapy with TMP-SMX (or azithromycin, if TMP-SMX was contraindicated) in outpatients and ceftriaxone in inpatients. However, layered patterns of resistance associated with concurrent S. flexneri and S. sonnei outbreaks in Seattle complicated selection of appropriate empiric therapy. Standard bacterial culture is not successful in some cases of PCR-positive shigellosis,20 and additionally, a typical three-day treatment course may be completed before AST results are available. Therefore, an alternative treatment approach was required. Based on the local epidemiology of resistance, patient-identified risk-group was found to correlate closely with antimicrobial susceptibility. Despite the rise of ciprofloxacin-resistant S. flexneri among PEH, shigellosis caused by both species in this demographic remained largely TMP-SMX-susceptible (S. flexneri: 48/58, 82.8% susceptible; S. sonnei: 24/30, 80% susceptible). Conversely, TMP-SMX and azithromycin resistance persisted among multiple S. flexneri and S. sonnei lineages in MSM, but these lineages remained largely ciprofloxacin-susceptible (S. flexneri: 50/55, 90.9% susceptible; S. sonnei: 15/20, 75% susceptible). As a result, guidelines for empiric outpatient therapy were updated to prioritize initial treatment of MSM in Seattle with ciprofloxacin. Treatment with ciprofloxacin is generally avoided when MIC is 0.12 μg/mL or higher, per CDC guidance,21 although some observations suggest that ciprofloxacin may still be clinically effective for strains with MICs of 0.12–1.0 μg/ml.22

The appropriateness of empiric treatment improved over time (p=0.033), following the introduction of risk-directed management guidelines. Despite high rates of MDR infection, we found that empiric therapy was appropriate for nearly 70% patients with available data. We attribute this to the use of rapid diagnostics for patients presenting with diarrhea, which allowed identification of most patients with shigellosis at the time of presentation. Rapid diagnosis has been shown to improve the appropriateness of antibiotic usage in patients with infectious diarrhea.23 Moreover, recognition of dominant clonal lineages infecting PEH and MSM populations, each exhibiting distinctive AMR phenotypes, allowed the development of risk-directed treatment guidelines that were broadly communicated to regional healthcare systems. The importance of appropriate empirical therapy is of particular importance in PEH, who are frequently lost to follow up, preventing the adjustment of antimicrobial therapy based on susceptibility testing.

The new outbreak with resistant S. flexneri and S. sonnei strains in PEH prompted several public health measures implemented by Public Health – Seattle & King County (PSHKC) to mitigate ongoing transmission. Locally-acquired isolates were prioritized for WGS at the Washington State PHL and advisories sent to healthcare providers with recommendations for optimal AST. A survey was conducted by PHSKC to identify fountains and other possible sources of acquisition within the most impacted downtown corridor of Seattle. Signage to discourage drinking from decorative water features and direct PEH to potable water sources was posted in these areas. Limited water and environmental sampling were conducted from non-potable water sources but were negative for Shigella spp. and fecal coliforms by bacterial culture. Infection prevention resources and guidance were disseminated to local homeless service providers and businesses. Outreach teams were organized to visit encampments and affected overnight shelters to provide health education and access to toilets, hygiene, and sanitation. Lastly, PHSKC urged early reopening of public restrooms, drinking fountains, and handwashing stations previously closed during the COVID-19 pandemic response, placement of clean water and handwashing/toilet stations near poorly-resourced encampments, and increased environmental cleaning in alleyways with evidence of public defecation in downtown Seattle.

DISCUSSION

This study involved genomic characterization of Shigella spp. isolated from Seattle adults with diarrhea over a period of five years. Demographics and clinical outcomes were analyzed to understand origins and patterns of transmission, and to develop treatment guidelines predicting AMR based on epidemiological risk factors. This work represents the collaborative efforts of local healthcare facilities, clinical and academic laboratories, antimicrobial stewardship, infection control, and public health teams. The outbreak was found to be driven by the concurrent emergence of new S. sonnei and S. flexneri strains among MSM in Seattle followed by rapid transmission within the local PEH population. Both outbreaks showed epidemiologic and phylogenomic similarity to strains previously reported in other countries, consistent with international dissemination of MDR Shigella clones as a cause of resurgent infection. Rapid diagnostics23 combined with risk-directed empiric therapy guidelines informed by detailed knowledge of local epidemiology enabled high rates of appropriate empiric therapy despite widespread MDR infection.

Prior studies have characterized regional outbreaks of shigellosis in increasing detail through WGS analysis.2,19 Our findings complement and build on prior reports in several important ways, as based on WGS findings, it was possible not only to characterize the origins and ongoing patterns of local Shigella transmission, but also to intervene using informed treatment guidelines and public heath interventions in real-time. These efforts maintained the efficacy of empiric therapy while mitigating the risk of convergence between chromosomally- and plasmid-mediated resistance traits circulating in the region (i.e., potential combination of chromosomally-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance in PEH with plasmid-borne resistance with other agents circulating among MSM in the same community, as seen in isolate 21–0082, Figure 2).

MSM are at risk for sexual transmission of enteric pathogens, including Shigella.22 Previous characterizations of Shigella outbreaks in developed nations have focused largely on MSM.2,24,25 The largest and most recent such characterization of an outbreak among MSM in the UK suggested the wider public health risk of potential spillover events in which resistant strains are transmitted beyond sexual networks to other at-risk groups.2 Whilst only observed in two sporadic cases among immunocompromised hosts in that series, here we describe multiple independent instances of S. sonnei and S. flexneri shared between MSM and PEH populations, with profound public health consequences. Shigellosis outbreaks among PEH in high-income countries have been recently reported, particularly on the West Coast of the US and Canada.3,7,24 Over half of Shigella isolates in our study originated from two discrete outbreaks first observed among MSM. Both outbreaks in PEH occurred in winter, consistent with the seasonality of shigellosis3,26 and possibly reflecting PEH gathering in shelters or other crowded environments during colder months. Although more frequently encountered in shigellosis in low- and middle-income countries, the sustained local transmission of S. flexneri described in this report highlights the opportunistic ability of this pathogen to afflict regions of high-income countries in which suitable living conditions and risk behaviors coexist.

While seeking to characterize the origins, transmission, and landscape of AMR among shigellosis cases in the Seattle region, we systematically reviewed sequence data and published reports from other regions. Our work benefited greatly from published case series paired with original sequence data and supports the perspective that networks of Shigella transmission are international and require a coordinated global response.27 Prior historic patterns with stable geographic distributions of Shigella sub-lineages28 are being rapidly transformed by the intercontinental spread of MDR strains. Our study adds to several recent descriptions of resurgent S. sonnei outbreaks following appearance of blaCTX–M–27 among MSM in the UK,2 Australia,19 Spain,29 and Canada.30 The identification of blaCTX–M–27 in a newly established S. flexneri lineage from Seattle in 2022 is consistent with an important role of this gene in driving emergent AMR.

Limitations of our study include the inability to demonstrate individual transmission events due to limited sampling density and reliance on clinical specimens. While some of these efforts would have been possible utilizing traditional epidemiologic and susceptibility information alone, the benefit of WGS substantially resolved areas of uncertainty regarding patterns of transmission and AMR, lending the confidence needed to solidify and refine these efforts.

Shigella outbreaks present an ongoing public health challenge in urban settings, disproportionally affecting MSM and marginalized populations with poor access to sanitation. This detailed analysis of a sustained shigellosis outbreak in Seattle has revealed multiple, parallel, and sequential outbreaks caused by discrete clonal lineages of Shigella in MSM and PEH. Despite a rising prevalence of globally disseminated MDR Shigella strains, our experience indicates that rapid diagnosis coupled with reflexive culture and treatment guidelines based on risk factors and local epidemiology can achieve high rates of appropriate empiric treatment.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Shigella spp. have been a growing global concern with many outbreaks, mainly affecting men who have sex with men (MSM), reported in the published literature. Over the last years, shigellosis outbreaks have been also reported among persons experiencing homelessness (PEH) on the West Coast of the United States and Canada. We searched the PubMed up to September 2022 using the terms “Shigella” and “antibiotic resistance.”

Added value of this study

In this study, we describe the sustained increase in shigellosis that has been reported in Seattle and King County, Washington State, USA since 2017, with a marked increase observed after 2020, particularly among PEH. The aim of the study is to better understand the community transmission of Shigella and spread of antimicrobial resistance in our population and to treat these multidrug-resistant infections more effectively. With the aid of whole-genome sequencing, we found that the sustained outbreak of shigellosis in our area was driven by the concurrent emergence of new S. sonnei and S. flexneri strains among MSM in Seattle followed by rapid transmission within the local PEH population. Both outbreaks showed epidemiologic and phylogenomic similarity to strains previously reported in other countries. Despite the high rates of antimicrobial resistance (50.6%), the rates of appropriate empiric therapy remained high (69.9%).

Implications of all the available evidence

Rapid diagnostics coupled with reflexive culture and treatment guidelines based on risk factors and local epidemiology can achieve high rates of appropriate empiric treatment. This study illustrates the value of WGS in resolving the origins and molecular determinants of ongoing disease outbreaks.

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

We declare no competing interests.

Dr. Giannoula S. Tansarli received research funding from GenMark Dx, Inc. for work not pertaining to this project.

Dr. Dustin R. Long received a K23 Mentored Research Training Award from the NIH/NIAMS for work not pertaining to this project.

Dr. Stephen J. Salipante received research grants from Vertex, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the NIH, for work not pertaining to this project. They also received consulting fees from Yale University.

Dr. Chloe Bryson-Cahn received honoraria for conference presentations on infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship and received support for attending the meetings for which she received honoraria in the past year: IDWeek, What’s New in Medicine, SHEA Spring Conference, and the Providence Annual ID Conference, for work not pertaining to this project.

Dr. Ferric C. Fang has been a paid consultant to bioMérieux, for work not pertaining to this project. They also received honoraria from Medscape for participation in educational web-basedpresentations on the diagnosis of enteric infections.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data sharing

Sequence data from this project has been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA791692, PRJNA862511). De-identified clinical metadata are also publicly available as Supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kotloff KL, Riddle MS, Platts-Mills JA, Pavlinac P, Zaidi AKM. Shigellosis. Lancet 2018;391:801–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charles H, Prochazka M, Thorley K, et al. Outbreak of sexually transmitted, extensively drug-resistant Shigella sonnei in the UK, 2021–22: a descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hines JZ, Jagger MA, Jeanne TL, et al. Heavy precipitation as a risk factor for shigellosis among homeless persons during an outbreak - Oregon, 2015–2016. J Infect 2018;76:280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranjbar R, Farahani A. Shigella: Antibiotic-Resistance Mechanisms And New Horizons For Treatment. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:3137–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivett H Increase in extensively drug resistant Shigella sonnei in Europe. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(7):e481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vu DT, Sethabutr O, Von Seidlein L, Tran VT, Do GC, Bui TC, et al. Detection of Shigella by a PCR assay targeting the ipaH gene suggests increased prevalence of shigellosis in Nha Trang, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(5):2031–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health Seattle-King County. Update on shigellosis outbreak among people experiencing homelessness in King County. In: Insider PH, ed.May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roosaare M, Puustusmaa M, Mols M, Vaher M, Remm M. PlasmidSeeker: identification of known plasmids from bacterial whole genome sequencing reads. PeerJ 2018;6:e4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015;31:3691–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suchard MA, Lemey P, Baele G, Ayres DL, Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol 2018;4:vey016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldgarden M, Brover V, Gonzalez-Escalona N, et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog facilitate examination of the genomic links among antimicrobial resistance, stress response, and virulence. Sci Rep 2021;11:12728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadouki Z, Day MR, Doumith M, Chattaway MA, Dallman TJ, Hopkins KL, et al. Comparison of phenotypic and WGS-derived antimicrobial resistance profiles of Shigella sonnei isolated from cases of diarrhoeal disease in England and Wales, 2015. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(9):2496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolde R (2019). _pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps_. R package version 1.0.12. at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap.)

- 14.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye C, Lan R, Xia S, et al. Emergence of a new multidrug-resistant serotype X variant in an epidemic clone of Shigella flexneri. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:419–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb HE, Tagg KA, Chen JC, et al. Novel quinolone resistance determinant, qepA8, in Shigella flexneri isolated in the United States, 2016. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkey J, Paranagama K, Baker KS, Bengtsson RJ, Weill FX, Thomson NR, et al. Global population structure and genotyping framework for genomic surveillance of the major dysentery pathogen, Shigella sonnei. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos-Madueno EI, Bernasconi OJ, Moser AI, et al. Rapid increase of CTX-M-producing Shigella sonnei Isolates in Switzerland due to spread of common plasmids and international clones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020;64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingle DJ, Andersson P, Valcanis M, et al. Prolonged outbreak of multidrug-resistant Shigella sonnei harboring bla CTX-M-27 in Victoria, Australia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020;64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prakash VP, LeBlanc L, Alexander-Scott NE, et al. Use of a culture-independent gastrointestinal multiplex PCR panel during a Shigellosis outbreak: considerations for clinical laboratories and public health. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:1048–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Update - CDC recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections with possible reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. June 7, 2018. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00411.asp. Last accessed on November 7, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman KL, Newman GS, Cybulski RJ, Fang FC. Gastroenteritis in men who have sex with men in Seattle, Washington, 2017–2018. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:109–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cybulski RJ Jr, Bateman AC, Bourassa L, Bryan A, Beail B, Matsumoto J, Cookson BT, Fang FC. Clinical impact of a multiplex gastrointestinal polymerase chain reaction panel in patients with acute gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilmer A, Romney MG, Gustafson R, et al. Shigella flexneri serotype 1 infections in men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada. HIV Med 2015;16:168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker KS, Dallman TJ, Field N, et al. Genomic epidemiology of Shigella in the United Kingdom shows transmission of pathogen sublineages and determinants of antimicrobial resistance. Sci Rep 2018;8:7389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gradus MS, Nichamin HD. Shigellosis winter trends in Milwaukee. Wis Med J 1989;88:17–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worley JN, Javkar K, Hoffmann M, et al. Genomic drivers of multidrug-resistant Shigella affecting vulnerable patient populations in the United States and abroad. mBio 2021;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connor TR, Barker CR, Baker KS, et al. Species-wide whole genome sequencing reveals historical global spread and recent local persistence in Shigella flexneri. Elife 2015;4:e07335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Cerero L, Stolz E, Pulido MR, Pascual A. Characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Shigella sonnei in Spain: expanding the geographic distribution of sequence cype 152/CTX-M-27 Clone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022;66:e0033422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaudreau C, Bernaquez I, Pilon PA, Goyette A, Yared N, Bekal S. Clinical and genomic investigation of an international ceftriaxone- and azithromycin-resistant Shigella sonnei cluster among men who have sex with men, Montreal, Canada 2017–2019. Microbiol Spectr 2022;10:e0233721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data from this project has been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA791692, PRJNA862511). De-identified clinical metadata are also publicly available as Supplemental material.