Abstract

Policy Points.

Little attention to date has been directed at examining how the long‐term services and supports (LTSS) environmental context affects the health and well‐being of older adults with disabilities.

We develop a conceptual framework identifying environmental domains that contribute to LTSS use, care quality, and care experiences.

We find the LTSS environment is highly associated with person‐reported care experiences, but the direction of the relationship varies by domain; increased neighborhood social and economic deprivation are highly associated with experiencing adverse consequences due to unmet need, whereas availability and generosity of the health care and social services delivery environment are inversely associated with participation restrictions in valued activities.

Policies targeting local and state‐level LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics stand to improve the health and well‐being of older adults with disabilities, particularly as it relates to adverse consequences due to unmet need and participation restrictions.

Context

Long‐term services and supports (LTSS) in the United States are characterized by their patchwork and unequal nature. The lack of generalizable person‐reported information on LTSS care experiences connected to place of community residence has obscured our understanding of inequities and factors that may attenuate them.

Methods

We advance a conceptual framework of LTSS‐relevant environmental domains, drawing on newly available data linkages from the 2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study to connect person‐reported care experiences with public use spatial data. We assess relationships between LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristic domains and person‐reported care adverse consequences due to unmet need, participation restrictions, and subjective well‐being for 2,411 older adults with disabilities and for key population subgroups by race, dementia, and Medicaid enrollment status.

Findings

We find the LTSS environment is highly associated with person‐reported care experiences, but the direction of the relationship varies by domain. Measures of neighborhood social and economic deprivation (e.g., poverty, public assistance, social cohesion) are highly associated with experiencing adverse consequences due to unmet care needs. Measures of the health care and social services delivery environment (e.g., Medicaid Home and Community‐Based Service Generosity, managed LTSS [MLTSS] presence, average direct care worker wage, availability of paid family leave) are inversely associated with experiencing participation restrictions in valued activities. Select measures of the built and natural environment (e.g., housing affordability) are associated with participation restrictions and lower subjective well‐being. Observed relationships between measures of LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics and care experiences were generally held in directionality but were attenuated for key subpopulations.

Conclusions

We present a framework and analyses describing the variable relationships between LTSS‐relevant environmental factors and person‐reported care experiences. LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics are differentially relevant to the care experiences of older adults with disabilities. Greater attention should be devoted to strengthening state‐ and community‐based policies and practices that support aging in place.

Keywords: social determinants of health, long‐term services and supports, disparities, caregiving, aging policy, aging

The magnitude and structure of resources to support quality of life and care in the context of population aging is a pressing topic of global consequence. 1 More than ten million older adults living in the United States report receiving help with daily activities to accommodate physical or cognitive disabilities. 2 These older adults rely on long‐term services and supports (LTSS) to undertake daily self‐care and household tasks through such resources as using assistive devices, receiving personal assistance and/or supportive services, or modifying features of their home.

The complexity and heterogeneity of LTSS delivery and financing pose unique challenges to our understanding and the design of policy and delivery reform efforts. LTSS may be delivered in individuals’ homes, in community settings, may be interwoven within supported housing or residential care facilities, or may drive transitions to long‐stay nursing homes. As persons with disabilities typically have co‐occurring chronic medical conditions, the availability, quality, and coordination with medical care is also critically important. 3 , 4

In the United States, LTSS spending is dominated by the publicly funded Medicaid program and out‐of‐pocket spending 5 , 6 while family and other unpaid caregivers provide most hands‐on assistance. 7 Approximately 10% of older adults carry private long‐term care insurance. 8 Medicare does not cover LTSS and limits the type of short‐term home care beneficiaries they may receive. 9 Importantly, the availability, quality, and accessibility of LTSS is highly variable across local geographies; services are typically arranged by individuals and families and subject to state and local health policies and resources within a fractured United States welfare and health care system. 10 , 11

There is growing appreciation that health outcomes are not only affected by services that are reimbursed and/or regulated by federal and state programs and private insurers but also by aspects of the environments in which individuals live, learn, work, play, worship, and age, including social and economic resources and attributes of the physical and natural environment such as housing and transportation. 12 , 13 , 14 Older adults’ social and economic resources, services use, and the built and natural environments they live in are recognized as important indicators of LTSS access and quality, 15 including—and perhaps especially among—older adults with disability who are socially disadvantaged. 16 Little attention to date has been directed at holistically conceptualizing or examining how the LTSS environmental context affects the health and well‐being of older adults with disabilities, as in this study. 17 , 18 , 19

Prior studies establish that characteristics of the environment such as racial segregation of nursing home residents, level of neighborhood disadvantage, and the structure of state Medicaid programs (e.g., state home and community‐based service expenditures) affect access and care quality in nursing homes and community‐based settings 20 , 21 , 22 and impact meaningful LTSS outcomes, such as the ability of older adults to participate in valued activities. 23 These inequities were recently brought into sharp focus by strikingly high rates of COVID‐19 infections and mortality experienced by older adults from racial and ethnic minoritized groups and those living in poverty. 24 , 25 , 26 Variability in LTSS access, quality, and outcomes has been observed by physical geography (e.g., counties, states, metropolitan vs. nonmetropolitan areas), by individuals’ economic status, such as insurance type (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, private pay), and by individual health needs, such as Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 However, this literature is diffuse and has yet to be systematically compiled within a broader conceptualization of the LTSS environment. Additionally, because of data constraints, our knowledge of how place‐based factors affect LTSS care quality has primarily relied on administrative data rather than self‐reported measures that reflect care experiences, 32 leaving researchers, policymakers, and providers with an incomplete picture of the LTSS landscape.

Conceptual Orientation

A key contribution of our work is the development of a conceptual framework identifying environmental domains that contribute to LTSS access, care quality, and care experiences. This work is informed by dynamic frameworks that conceptualize quality of life and care in the context of disability as resulting from the interplay of individual health, behaviors, and characteristics of the physical, social, and technological environments in which activities are carried out 33 , 34 , 35 as well as consensus frameworks relating LTSS availability, comprehensiveness, and accessibility to care delivery processes and outcomes. 36 , 37 We recognize that within this context, individual views and preferences represent true north in assessments of choice and control, community participation, and experiences of care. 32

Table 1 depicts multiple levels and domains of the environment. Following the National Institute on Aging Health Disparities Framework 38 and other heuristics that elucidate drivers of population health and equity, 39 , 40 we identify priority key populations that often experience disparately poorer LTSS care experiences, including: racial/ethnic minority groups, 41 socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, 41 , 42 rural populations, 27 persons living with disability, 43 and sexual/gender minority groups. 44 The Y‐axis differentiates three LTSS‐relevant environmental domains that are known to affect care experiences. 45 , 46 Social and economic factors are those that influence the distribution of goods and services and social networks, such as measures of social services spending generosity, the types and rates of employment, wage adequacy—and sociocultural factors such as civic engagement, perceptions of social cohesion, and crime. 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 Health care and social service delivery encompasses the structure and generosity of programs and policies such as Medicaid generosity; the presence of managed long‐term services and supports (MLTSS); health care payer mix (i.e., state Medicare Advantage penetration) 31 ; and factors affecting workforce capacity (both direct care workers and family caregivers) such as wage level, training requirements, paid leave policies, supply, and supports. The built and natural physical environment includes transportation and land use, physical communication infrastructure, and physical housing. 51 , 52 , 53 , 54

Table 1.

Long‐Term Services and Support Environment Framework

| Key populations: racial/ethnic minority groups, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, rural populations, disability populations, sexual/gender minority groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Levels | |||

|

Societal (e.g., State) |

Community (e.g., MSA, HRR) |

Household | |

| Environmental Domains |

Quality (e.g., Quality of Services, Adequacy of Policy Implementation) |

||

| Social and Economic | |||

| Economic factors | SNAP generosity and eligibility a | Employment, wages, education, poverty a | Income and assets, education, receipt of public assistance |

| Sociocultural factors | Community participation b | Crime, c social cohesion, racial residential segregation a , d | Religiosity, language, cultural beliefs |

| Health Care and Social Services Delivery | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Financing | Medicaid HCBS generosity, e minimum wage, MLTSS presence, f Medicare Advantage enrollees, g State Medicaid Enrollment a Title III/Older Americans Act Spending h | Medicaid enrollment, a health insurance mix, a Medicare spending i | Medicaid enrolled, source of paid help (e.g., state Medicaid program, private pay), long‐term care insurance |

| Direct care workforce | Training requirements | Supply, wages, j commute times | Presence and types of paid help |

| Family caregiving | Availability of state paid family leave, k paid sick leave, k unemployment policies l | Service delivery environment availability and quality (e.g., senior centers, adult day care centers) n | Caregiver(s) relationship, type of help, hours of care |

| Social services | LTSS scorecard characteristics m | Types of services received | |

| Built and Natural Physical Environment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation and land use | Presence of State Coordination Council, o state emergency preparedness regulations | Complete street policies, zoning practices, population density | Car ownership, driving status, modes of transportation |

| Communication infrastructure | State web accessibility regulations p | Proportion of population with subscriptions to broadband internet a | Internet use, disability severity, type of accommodations |

| Housing infrastructure | – | Household value to income ratio, a median housing stock age, a proportion of housing with physical deficiencies f | Residence type (community, residential care, nursing home), adequacy, housing quality issues, accessibility features, rent vs. own, residential services |

Abbreviations: HCBS, home‐ and community‐based services; HRR, hospital referral region; LTSS, long‐term services and supports; MLTSS, managed long‐term services and supports; MSA, metropolitan statistical area; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

The table is not exhaustive and includes example measures. Key populations reflect persons from groups who disproportionately experience poorer LTSS‐related care quality and quality outcomes.

American Community Survey

Community Population Survey Civic Engagement Supplement

Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics

National Equity Atlas

Truven Health Analytics

Mathematica

Kaiser Family Foundation

Administration for Community Living

Dartmouth Atlas

Bureau of Labor Statistics: Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics

National Conference of State Legislatures

National Partnership for Women and Families

American Association of Retired Persons LTSS Scorecard

National Neighborhood Data Archive (NaNDA), North American Industry Classification System code 624120: services for the elderly and people with disabilities, such as senior centers, adult day care centers, and disability support groups

State Human Service Transportation Coordinating Councils: An Overview and State Profiles

The Americans with Disabilities Act, Sections 504 and 508 of the Rehabilitation Act, and state laws

The X‐axis of the matrix shows that LTSS is interwoven across multiple social and political levels. We differentiate three levels: societal, community, and household. The societal level refers to macrolevel federal and state social and public policies and programs that directly or indirectly affect LTSS access or care quality; this level also situates political ideologies and values that influence social and public policies. Community refers to the conditions and context of local geographies, such as county, city, census tract, metropolitan statistical area, or hospital referral region that result from macrolevel policies; is another level of social and political policy generation; and reflects practical dependencies of living in proximity to others and in a defined geographical area. 55 Household refers to the conditions and context (e.g., income and assets, use of paid help, disability severity) affecting care arrangements and service use within the immediate living environment. Finally, because the effects of accessing services and being exposed to LTSS‐relevant policies likely impact older adult and family caregiver care experiences, we acknowledge considerations for quality, ranging from quality of care to adequacy of policy implementation.

This study quantitatively examines how LTSS‐relevant environmental domains relate to person‐reported care experiences that reflect foundational elements of care quality. We additionally explore the extent to which observed relationships hold across vulnerable subgroups of older adults. Our goal in undertaking this work is to shed light on the role of LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics to outcomes that matter as a step toward informing related research, policy, and delivery reform.

Methods

Data and Measurement

The present study draws on the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), a nationally representative study of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 years old and older, linked to public use spatial data sets of contextual factors. The NHATS is an annual survey that was originally fielded in 2011, with a 2015 sample replenishment. Older age groups and Black older adults are oversampled. In‐person interviews are conducted with study participants or proxy respondents if the participant is unable to respond. 56 This study includes 2,411 (weighted N = 10,350,985) community‐living older adults who responded to the 2015 wave and reported receiving help with self‐care, mobility, or household activities (for a health reason).

Select LTSS‐relevant measures are drawn from the American Community Survey (ACS), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and other publicly available data sources that characterize LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics at the state and community level from our framework (Table 1). The ACS is conducted by the US Census Bureau to provide annual information about states, communities, and people, including sociodemographic, employment, and disability characteristics. 57 The BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics Survey collects information on labor market activity and working conditions in the United States, including the direct care workforce. 58 The Dartmouth Atlas draws on Medicare and Medicaid data to compute measures reflecting regional and local markets. 59 Finally, we compiled selected state‐level measures of LTSS‐relevant policies and programs.

Our approach to selecting contextual measures draws on the logic put forward by Remington and colleagues 19 in prioritizing measures that can be improved or modified through community action; are valid, reliable, recognized, and used by others; draw on data that are available for all geographic areas of the United States at low or no cost; are temporally aligned with data over the observation period; and reflect parsimony to exclude redundancy, with fewer measures in principle being better than more. When feasible and appropriate, we selected contextual measures at the more granular level (e.g., census tract rather than county, state rather than federal). In the present analysis, measures at the societal level focus on state‐level policies and regulations in the context of the United States.

Measures

Key Population Characteristics

These characteristics include age, gender, race/ethnicity, Medicaid enrollment, severity of disability, and probable dementia. We include categorical measures of age (65‐74 years old, 75–84 years old, and 85 years old and older), and race/ethnicity, including non‐Hispanic White and racial/ethnic minoritized groups (i.e., non‐Hispanic Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and other). Medicaid enrollment is self‐reported. Severity of disability refers to the number of self‐care and mobility daily activities for which older adults were receiving help. Probable dementia refers to a composite measure from self‐reported dementia or dementia diagnoses, a score indicating dementia on the AD8 Dementia Screening Interview, or performance on cognitive tests of memory, orientation, and executive function. 60

LTSS‐Relevant Environmental Characteristics

The characteristics are described for each domain. For each measure, we specify the level of geography (societal, community, or household). We categorized continuous measures without established cut points by tertile for our analytic sample and replaced missing data with state‐level means.

1. Social and Economic Domain. We include census‐tract–level measures from the ACS for the proportion of residents living in poverty, are unemployed, and receiving public assistance (i.e., Social Security Income, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or General Assistance), 61 categorized by tertile. Neighborhood social cohesion refers to a composite measure from three NHATS items, including how well people in the neighborhood know each other, are willing to help each other, and can be trusted, with each question answered on a three‐point scale (do not agree, agree a little, agree a lot). The composite measures averages responses to the three items, with higher scores reflecting greater cohesion. Following prior work, scores are dichotomized; scores below the tenth percentile represent low cohesion. 62

2. Health Care and Social Services Delivery Domain. Medicaid generosity refers to the proportion of state‐specific Medicaid LTSS expenditures devoted to home‐ and community‐based services (HCBS; versus nursing homes) in 2015 from publicly available data, 63 categorized by tertile for the analytic sample. A dichotomous measure indicates state presence of MLTSS programs delivered through capitated Medicaid‐managed care programs that have been shown to be associated with care and quality of life outcomes. 64 Minimum wage refers to whether the state was at or below, or exceeded, the federal level in 2015. 65 , 66 We include the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage by state (Medicare Advantage penetration), which has had variable impacts on older adult care experiences. 31 , 67 as well as the percentage of state residents enrolled in Medicaid. 57 Paid family and sick leave refers to states having active policies in 2015. 68 States that have enacted the Unemployment Modernization Act to support caregivers returning to work are identified and included as well. 69 We also include a measure reflecting Aging and Disability Resource Center/No Wrong Door functions that help families access LTSS. We include a measure from the American Association of Retired Persons that rates state progress toward developing a single statewide No Wrong Door System with a composite indicator (0%‐100%) from 41 criteria across five areas that include the following: (1) state governance and administration, (2) target population, (3) public outreach and coordination and key referral sources, (4) person‐centered counseling, and (5) streamlined eligibility for public programs. 70 We also include information about home health aides and personal care aides. 71 From the BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics Survey, we assess direct care workforce wages for home health aides and personal care aides at the level of the metropolitan statistical area, categorized by tertile of mean hourly wages. 58 Medicare reimbursement per beneficiary is calculated from Medicare fee‐for‐service administrative claims data and assessed at the hospital referral region, which represents the health care market for medical care, and is categorized by tertile. 59

3. Built and Natural Physical Environment Domain. We include state‐level dichotomous measures of transportation and communication infrastructure, which refer to the presence of a state human service transportation coordination council 72 and state web accessibility regulations, respectively. 73 Several measures representative of the built and natural physical environment draw on the ACS at the census‐tract level. Neighborhood broadband subscription rates are categorized by tertile. 74 The ACS provides data that describe mortgage and rent value to household income. 57 A categorical measure was created (based on tertiles) that reflected the percentage of households in a census tract in which the household value was greater than three times that of the household income. Mean neighborhood housing age is also categorized by tertile. 57 Deficits in housing quality refer to NHATS interviewer observations of paint peeling inside the home, pests, broken furniture, flooring problems, broken windows, crumbling foundation, siding issues, roof problems, and/or broken stairs, as previously described. 75 Residence type refers to traditional community setting or residential care setting based on NHATS interviewer observation. 56

Care Experiences

From NHATS, we derive three self‐ or proxy‐reported measures of care experiences that reflect outcomes that matter to persons living with disability. Adverse consequences due to unmet care needs refers to experiencing one or more activity‐specific negative consequences because of no one being available to provide help (if help was reported as being needed) or the activity being too difficult to perform on their own (if difficulty was reported), as in prior work. 76 Adverse consequences related to self‐care include the following: going without eating; being unable to shower, take a bath, or wash up; wetting or soiling yourself; or going without getting dressed. Adverse consequences related to mobility include the following: having to stay in the house, being unable to get around inside the home, and having to stay in bed. 76 Participation restrictions refer to being unable to visit friends and family, attend religious services, attend club meetings or group activities, or go out for enjoyment because of health and functioning reasons for the subset of participants who reported each activity as “very important” or “somewhat important,” as in prior work. 77 Subjective well‐being is a composite measure of six items reflecting how often in the last month participants reported positive and negative emotions of being cheerful, bored, full of life, or upset (each scored from 0 for “never” to 4 for “every day”) and self‐realization that “my life has meaning and purpose” and “I feel confident and good about myself” (each scored 2 for “agree a lot” to 0 for “not at all”). Responses to items are summed, and the composite measure ranges from 0 and 20, as previously described. 2 , 78 We dichotomize this measure to contrast the highest quartile of well‐being (18 and above) with lower scores (≤17). Measures of adverse consequences due to unmet care needs and participation restrictions include participants who responded themselves or relied on a proxy respondent, whereas measures of subjective well‐being are limited to participants who self‐reported survey responses.

Analysis

We first examine how participant key population characteristics relate to the three care experiences of interest: adverse consequences due to unmet care needs, participation restrictions, and subjective well‐being. We then descriptively examine selected measures within LTSS‐relevant environmental domains in relation to the three care experiences of interest. To assess statistical significance of comparisons, we use Pearson's chi‐square and t‐tests. Participants missing a subjective well‐being score because of item nonresponse (6%) were excluded from final analyses. Additionally, analyses of subjective well‐being are limited to NHATS participants who self‐reported survey responses; those who relied on a proxy respondent (n = 409) were excluded. Finally, we examined consistency in observed relationships for several key subpopulations—racial and ethnic minoritized groups, Medicaid‐enrolled older adults, and those living with dementia—by charting the directionality and statistical significance of relationships for LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics and our three outcomes of interest for our overall sample and each of key population subgroup. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 15, 79 using weighted data and variables that account for the NHATS's complex survey design. 80

Results

Of an estimated 10.3 million older adults living with disabilities in community settings in 2015, 36.9% experienced adverse consequences due to unmet care needs, 40.8% experienced participation restrictions in valued activities, and 84.1% were categorized as having lower subjective well‐being (Table 2). Older adults who were members of racial or ethnic minoritized groups, were Medicaid enrolled, received help with greater numbers of daily activities, and were living with dementia were more likely to experience adverse consequences due to unmet care needs. Older adults who were female and received help with greater numbers of daily activities were more likely to report participation restrictions. Older adults who were White and received help with greater numbers of daily activities were more likely to report lower subjective well‐being.

Table 2.

Care Experiences by Characteristics of Community‐Living Older Adults with Disabilities

| Adverse Consequence Because of Unmet Need | Participation Restrictions in Valued Activities | Subjective Well‐Being a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | No | Yes | p | High | Lower | p | |

| Weighted estimate | 6,529,741 | 3,821,243 | 6,126,476 | 4,224,508 | 1,319,162 | 6,960,196 | |||

| Weighted (row, %) | 63.1 | 36.9 | 59.2 | 40.8 | 15.9 | 84.1 | |||

| Unweighted n | 1,520 | 891 | 1,427 | 984 | 319 | 1,565 | |||

| Key Population Characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 65‐74 | 63.3 (327) | 36.7 (190) | 0.75 | 56.6 (298) | 43.4 (219) | 0.27 | 14.7 (65) | 85.3 (388) | 0.14 |

| 75‐84 | 62.0 (574) | 38.0 (346) | 60.3 (540) | 39.7 (380) | 14.7 (118) | 85.3 (640) | |||

| 85+ | 64.2 (619) | 35.8 (355) | 61.2 (589) | 38.8 (385) | 20.0 (139) | 80.0 (537) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 66.2 (534) | 33.8 (267) | 0.08 | 67.5 (540) | 32.5 (261) | <0.001 | 16.9 (116) | 83.1 (500) | 0.56 |

| Female | 61.3 (986) | 38.7 (624) | 54.6 (887) | 45.4 (723) | 15.4 (203) | 84.6 (1,065) | |||

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 64.7 (952) | 35.3 (512) | 0.05 | 58.4 (876) | 41.6 (588) | 0.29 | 13.9 (181) | 86.1 (1,018) | <0.01 |

| Racial/ethnic minoritized groups | 59.2 (568) | 40.8 (379) | 61.1 (551) | 38.9 (396) | 21.7 (138) | 78.3 (547) | |||

| Medicaid enrolled | |||||||||

| Yes | 54.8 (316) | 45.2 (263) | <0.001 | 60.4 (60.4) | 39.6 (253) | 0.58 | 14.0 (67) | 86.0 (377) | 0.31 |

| No | 65.4 (1,204) | 34.6 (628) | 58.8 (1,101) | 41.2 (731) | 16.5 (252) | 83.5 (1,188) | |||

| Number of daily activities receiving help with (mean, 95% CI) | 1.18 (1.08, 1.28) | 2.99 (2.81, 3.17) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.42, 1.76) | 2.28 (2.08, 2.48) | <0.001 | 1.2 (0.93, 1.43) | 1.5 (1.41, 1.58) | 0.01 |

| Probable dementia b | |||||||||

| Yes | 56.6 (375) | 43.4 (283) | <0.01 | 60.8 (401) | 39.2 (257) | 0.40 | – | – | – |

| No | 65.1 (1,145) | 35.0 (608) | 58.7 (1,026) | 41.3 (727) | – | – | – | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NHATS, National Health and Aging Trends Study.

These data feature a sample of 2,411 NHATS participants 65 years old or older who received assistance with routine household, self‐care, or mobility activities and live in traditional community settings or residential care settings in 2015.

The sample excludes 409 NHATS participants who relied on a proxy respondent.

Low subjective well‐being was not reported for dementia comparison because of insufficient sample of older adults with probable dementia. .

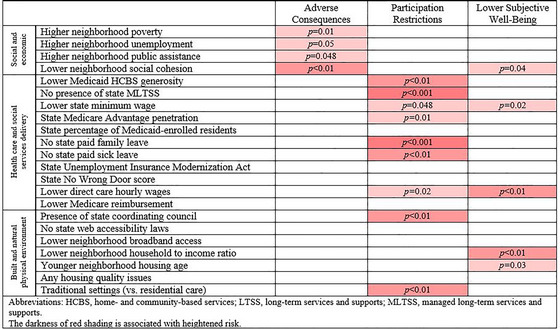

LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics were highly associated with older adults’ care experiences, but the direction and strength of relationships varied by domain (Table 3 and Figure 1). The experience of adverse consequences due to unmet care needs was most strongly related to measures from within the social and economic domain. Adverse consequences were more common for older adults living in neighborhoods with the highest (versus lowest) proportion of residents living in poverty (42.9% vs. 34.1%, p = 0.01), unemployed (41.1% vs. 34.0%, p = 0.05), receiving public assistance (41.5% vs. 36.6%, p = 0.048), and in neighborhoods with lower (versus higher) social cohesion (43.2% vs. 35.2%, p < 0.01). None of the measures within the domains of health care and social services delivery environment or built and natural environment were statistically significant in relation to adverse consequences due to unmet care needs.

Table 3.

LTSS Environmental Characteristics and Care Experiences of Community‐Living Older Adults with Disabilities

| Adverse Consequences | Participation Restrictions | Subjective Well‐Being a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | No | Yes | p | High | Lower | p | |

| Weighted estimate | 6,529,741 | 3,821,243 | 6,126,476 | 4,224,508 | 1,894,264 | 6,960,196 | |||

| Percentage (unweighted n) | 63.1 (1,520) | 36.9 (891) | 59.2 (1,427) | 40.8 (984) | (319) | 78.6 (1,565) | |||

| Social and Economic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood poverty | |||||||||

| T1 (<9.5%) | 65.9 (521) | 34.1 (283) | 0.01 | 60.9 (497) | 39.1 (307) | 0.32 | 16.5 (103) | 83.5 (519) | 0.90 |

| T2 (9.5%‐18.9%) | 64.6 (519) | 35.4 (289) | 56.8 (464) | 43.2 (344) | 15.4 (106) | 84.6 (524) | |||

| T3 (≥19.0%) | 57.1 (480) | 42.9 (319) | 59.8 (466) | 40.2 (333) | 15.8 (110) | 84.2 (522) | |||

| Neighborhood unemployment | |||||||||

| T1 (<6.3%) | 66.0 (532) | 34.0 (272) | 0.05 | 57.0 (477) | 43.0 (327) | 0.38 | 14.5 (101) | 85.5 (541) | 0.45 |

| T2 (6.3%‐10.7%) | 63.3 (507) | 36.7 (297) | 61.5 (477) | 38.5 (327) | 17.9 (108) | 82.1(531) | |||

| T3 (≥10.8) | 58.9 (481) | 41.1 (322) | 59.4 (473) | 40.6 (330) | 15.5 (110) | 84.5 (493) | |||

| Neighborhood receipt of public assistance | |||||||||

| T1 (<19.0%) | 63.4 (510) | 36.6 (292) | 0.048 | 60.9 (498) | 39.1 (304) | 0.28 | 16.1 (100) | 83.9 (513) | 0.62 |

| T2 (19.0%‐41.6%) | 66.2 (525) | 33.8 (277) | 56.6 (455) | 43.4 (347) | 16.9 (110) | 83.1 (511) | |||

| T3 (≥41.7%) | 58.5 (481) | 41.5 (320) | 60.4 (471) | 39.6 (330) | 14.3 (107) | 85.7 (537) | |||

| Neighborhood social cohesion | |||||||||

| Low | 56.8 (281) | 43.2 (202) | <0.01 | 55.4 (272) | 44.6 (211) | 0.15 | 12.4 (53) | 87.6 (321) | 0.04 |

| High | 64.8 (1,239) | 35.2(689) | 60.2 (1,155) | 39.8 (773) | 16.9 (266) | 83.1 (1,244) | |||

| Health Care and Social Service Delivery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid HCBS generosity | |||||||||

| T1 (<29.6%) | 63.2 (546) | 36.8 (318) | 0.16 | 54.5 (474) | 45.5 (390) | <0.01 | 13.1 (97) | 86.9 (588) | 0.25 |

| T2 (29.6%‐42.3%) | 65.6 (507) | 34.4 (285) | 58.9 (472) | 41.1 (320) | 17.8 (121) | 82.2 (517) | |||

| T3 (>42.3%) | 60.6 (467) | 39.4 (288) | 63.9 (481) | 36.1 (274) | 17.0 (101) | 83.0 (460) | |||

| State MLTSS | |||||||||

| Yes | 62.8 (884) | 37.2 (526) | 0.76 | 62.7 (865) | 37.3 (545) | <0.001 | 16.6 (196) | 83.4 (887) | 0.52 |

| No | 63.5 (636) | 36.5 (365) | 53.8 (562) | 46.2 (439) | 14.9 (123) | 85.1 (678) | |||

| State minimum wage | |||||||||

| At or below federal minimum | 62.4 (583) | 37.6 (355) | 0.67 | 55.8 (520) | 44.2 (418) | 0.048 | 13.1 (119) | 86.9 (641) | 0.02 |

| Above federal minimum | 63.5 (937) | 36.5 (536) | 61.1 (907) | 38.9 (566) | 17.6 (200) | 82.4 (924) | |||

| State Medicare Advantage penetration | |||||||||

| T1 (<29%) | 64.1 (495) | 35.9 (303) | 0.31 | 54.4 (452) | 45.6 (346) | 0.01 | 17.5 (116) | 82.6 (514) | 0.30 |

| T2 (29%‐38%) | 61.5 (742) | 38.5 (444) | 60.1 (701) | 39.9 (485) | 14.4 (148) | 85.6 (768) | |||

| T3 (≥38%) | 65.9 (283) | 34.1 (144) | 64.5 (274) | 35.5 (153) | 17.8 (55) | 82.3 (283) | |||

| State percentage of residents who are Medicaid enrolled | |||||||||

| T1 (<18.4%) | 64.5 (501) | 35.5 (282) | 0.38 | 55.6 (442) | 44.4(341) | 0.14 | 85.0 (525) | 15.0 (103) | 0.87 |

| T2 (18.4%‐20.8%) | 64.0 (532) | 36.0 (308) | 59.9 (503) | 40.1 (337) | 83.7 (557) | 16.3 (120) | |||

| T3 (≥20.8%) | 60.9 (487) | 39.1 (301) | 64.7 (482) | 38.3 (306) | 83.6 (483) | 16.4 (96) | |||

| State paid family leave | |||||||||

| Yes | 60.4 (214) | 39.6 (135) | 0.40 | 68.2 (224) | 31.8 (125) | <0.001 | 18.3 (45) | 81.7 (195) | 0.52 |

| No | 63.6 (1,306) | 36.4 (756) | 57.4 (1,203) | 42.6 (859) | 15.5 (274) | 84.5 (1,370) | |||

| State paid sick leave | |||||||||

| Yes | 60.8 (276) | 39.2 (169) | 0.40 | 66.2 (288) | 33.8 (157) | <0.01 | 17.8 (55) | 82.2 (259) | 0.49 |

| No | 63.7 (1,244) | 36.3 (722) | 57.4 (1,139) | 42.6 (827) | 15.5 (264) | 84.5 (1,306) | |||

| State Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act | |||||||||

| Yes | 60.9 (653) | 39.1 (403) | 0.08 | 61.6 (653) | 44.2 (403) | 0.13 | 16.5 (139) | 83.5 (683) | 0.65 |

| No | 65.1 (867) | 34.9 (488) | 57.1 (774) | 55.8 (581) | 15.4 (180) | 84.6 (882) | |||

| State No Wrong Door score | |||||||||

| T1 (<50%) | 60.3 (514) | 39.7 (321) | 0.23 | 60.3 (500) | 39.7 (335) | 0.67 | 17.5 (117) | 82.5 (528) | 0.38 |

| T2 (50%‐79%) | 63.8 (535) | 36.2 (309) | 57.6 (483) | 42.4 (361) | 13.9 (105) | 86.1 (564) | |||

| T3 (≥79%) | 65.3 (471) | 34.7 (261) | 59.7 (444) | 40.3 (288) | 16.5 (97) | 83.5 (473) | |||

| Mean hourly wages of direct care workers | |||||||||

| T1 (<$10.29) | 61.9 (521) | 38.1 (329) | 0.16 | 54.3 (455) | 45.7 (395) | 0.02 | 11.6 (101) | 88.4 (576) | <0.01 |

| T2 ($10.29‐$11.26) | 66.1 (534) | 33.9 (275) | 61.5 (502) | 38.5 (307) | 18.2 (119) | 81.8 (512) | |||

| T3 ($11.26‐$14.69) | 61.2 (465) | 38.8 (287) | 61.7 (470) | 38.3 (282) | 18.2 (99) | 81.8 (477) | |||

| Mean Medicare reimbursement per beneficiary | |||||||||

| T1 (<$9,139.80) | 62.7 (459) | 37.3 (263) | 0.94 | 55.4 (423) | 44.6 (299) | 0.20 | 15.0 (102) | 85.0 (496) | 0.27 |

| T2 ($9,139.80‐$9,998.37) | 62.8 (513) | 37.2 (313) | 60.9 (489) | 39.1 (337) | 14.5 (98) | 85.5 (546) | |||

| T3 (>$9,998.37) | 63.7 (548) | 36.3 (315) | 60.6 (515) | 39.4 (348) | 18.2 (119) | 81.8 (523) | |||

| Built and Natural Physical Environment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of state coordination council | |||||||||

| Yes | 63.9 (512) | 36.1 (290) | 0.58 | 54.6 (451) | 45.4 (351) | <0.01 | 13.8 (92) | 86.2 (545) | 0.28 |

| No | 62.7 (1,008) | 37.3 (601) | 61.4 (976) | 38.6 (633) | 17.0 (227) | 83.0 (1,020) | |||

| Presence of state web accessibility laws | |||||||||

| Yes | 63.2 (1,332) | 36.8 (782) | 0.70 | 59.8 (1,258) | 40.2 (856) | 0.17 | 16.0 (275) | 84.0 (1,365) | 0.80 |

| No | 61.9 (188) | 38.1 (109) | 54.6 (169) | 45.4 (128) | 15.2 (44) | 84.8 (200) | |||

| Neighborhood broadband access | |||||||||

| T1 (<74.2%) | 60.1 (487) | 39.9 (317) | 0.13 | 58.8 (459) | 41.2 (345) | 0.95 | 16.2 (109) | 83.8 (541) | 0.98 |

| T2 (74.2%‐85.7%) | 65.9 (527) | 34.1 (278) | 59.7 (482) | 40.3 (323) | 15.8 (106) | 84.2 (518) | |||

| T3 (≥85.8%) | 62.6 (506) | 37.4 (296) | 59.0 (486) | 41.0 (316) | 15.9 (104) | 84.1 (506) | |||

| Mean household value to income ratio | |||||||||

| T1 (<0.03) | 62.1 (495) | 37.9 (306) | 0.72 | 56.8 (456) | 43.2 (345) | 0.13 | 11.8 (98) | 88.2 (538) | <0.01 |

| T2 (0.30‐0.42) | 64.2 (507) | 35.8 (290) | 57.5 (463) | 42.5 (334) | 14.4 (103) | 85.6 (537) | |||

| T3 (≥0.43) | 63.1 (510) | 36.9 (289) | 62.8 (499) | 37.2 (300) | 21.0 (116) | 79.0 (481) | |||

| Mean neighborhood housing age | |||||||||

| T1 (<1966) | 64.5 (519) | 35.5 (298) | 0.45 | 62.3 (502) | 37.7 (315) | 0.37 | 19.6 (117) | 80.4 (504) | 0.03 |

| T2 (1966‐1980) | 61.2 (500) | 38.8 (306) | 58.0 (468) | 42.0 (338) | 17.0 (115) | 83.0 (523) | |||

| T3 (≥1981) | 63.9 (493) | 36.1 (281) | 57.8 (448) | 42.2 (326) | 12.2 (87) | 87.8 (526) | |||

| Any housing quality issues | |||||||||

| Yes | 60.3 (273) | 39.7 (171) | 0.27 | 61.6 (274) | 38.4 (170) | 0.46 | 13.6 (60) | 86.4 (311) | 0.25 |

| No | 63.7 (1,247) | 36.3 (720) | 58.7 (1,153) | 41.3 (814) | 16.5 (259) | 83.5 (1,254) | |||

| Residence type | |||||||||

| Traditional community | 63.2 (1,341) | 36.8 (784) | 0.72 | 57.8 (1,229) | 42.2 (896) | <0.01 | 15.5 (283) | 84.5 (1,411) | 0.14 |

| Residential care setting | 62.0 (179) | 38.0 (107) | 69.3 (198) | 30.7 (88) | 20.1 (36) | 79.9 (154) | |||

Abbreviations: HCBS, home‐ and community‐based services; LTSS, long‐term services and supports; MLTSS, managed long‐term services and supports; NHATS, National Health and Aging Trends Study; T1, tier 1.

These data feature NHATS 2015 adults 65 years old or older who receive assistance with routine household, self‐care, or mobility activities and live in traditional community settings or residential care settings.

The sample excludes 409 NHATS respondents when a proxy person provided the responses. Cases with missing data are excluded for subjective well‐being (n = 118).

Figure 1.

LTSS Environment Characteristics and Older Adults' Care Experiences [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Participation restrictions in valued activities were most consistent in relationship to environmental measures within the health care and social service delivery domain. Participation restrictions were more commonly experienced among older adults living in states with the lowest (versus highest) tertile of Medicaid HCBS generosity (45.5% vs. 36.1%, p < 0.01), without (versus with) MLTSS (46.2% vs. 37.3%, p < 0.001), with a state minimum wage set at or below the federal minimum (vs. exceeding) (44.2% vs. 38.9%, p = 0.048), in the lowest (versus highest) tertile of Medicare Advantage penetration (45.6% vs. 35.5%, p = 0.01), and those living in states without paid family leave (42.6% vs. 31.8%, p < 0.001) or paid sick leave (42.6% vs. 33.8%, p < 0.01) and in metropolitan statistical areas in which direct care workers earn the lowest (versus highest) tertile of mean hourly wages (45.7% vs. 38.3%, p = 0.02). Within the built and natural environment domain, participation restrictions were more common among those living in states with (versus without) transportation coordination councils (45.4% vs. 38.6%, p < 0.01) and in traditional community versus residential care settings (42.2% vs. 30.7%, p < 0.01). None of the measures within the social and economic domain were associated with experiencing participation restrictions.

Lower subjective well‐being was not consistently associated with environmental measures in any one domain. Within the social and economic domain, lower subjective well‐being was more often reported among older adults living in neighborhoods with low social cohesion (versus high) (87.6% vs. 83.1%, p = 0.04). Within the health care and social services domain, lower subjective well‐being was more common among older adults living in states at or below (versus exceeding) the federal minimum wage (86.9% vs. 82.4%, p = 0.02) and in regions with the lowest (versus highest) tertile of direct care worker mean hourly wages (88.4% versus 81.8%, p < 0.01). Within the built and natural environment domain, lower subjective well‐being was more common among those living in neighborhoods with the lowest (versus highest) household value to income ratio (88.2% vs. 79.0%, p < 0.01) and younger (versus older) mean neighborhood housing age (87.8% vs. 80.4%, p = 0.03).

We also conducted subsequent analyses to examine relationships between measures of LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics and care experiences among several key subpopulations; the findings were generally held in directionality but were attenuated (Appendices 1, 2, 3). For example, among racial and ethnic minoritized groups, three of the five measures within the health care and social service delivery domain retained statistical significance in relation to participation restrictions: state MLTSS, paid family leave, paid sick leave, and Medicare reimbursement rates. For Medicaid‐enrolled older adults, lower Medicare Advantage penetration and lower No Wrong Door Composite scores were associated with experiencing participation restrictions. Additionally, lower direct care worker wages were associated with lower subjective well‐being among Medicaid‐enrolled older adults. Among persons living with dementia, those living in states with no state paid sick leave policy more often experienced participation restrictions. Higher wages for direct care workers were inversely associated with participation restrictions among older adults living with dementia.

Discussion

This study advances a conceptual framework and provides quantitative evidence linking LTSS‐relevant environmental domains to meaningful, person‐centered outcomes for persons with disability. Drawing on this framework, we find systematic variability across domains of LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics in the strength and directionality of relationships to person‐reported care experiences. Measures of environmental social and economic deprivation were strongly associated with adverse consequences due to unmet care needs. Measures of generosity in the health care and social services delivery environment were inversely associated with participation restrictions and, to a lesser degree, subjective well‐being. Measures of the built and natural environment were more erratic in relation to the three care experiences of interest in this analysis. Study results, which extend to key subpopulations, provide evidence that interventional strategies and their evaluation should extend beyond the individual person to the environments in which individuals carry out their lives.

Our study is the first to broadly conceptualize and systematically evaluate measures across domains of LTSS‐relevant environmental features and person‐reported care experiences. Our framework may be applied to different target populations, including adults younger than 65 years old living with disabilities, who also often benefit from community‐based LTSS. The substantial proportion of older adults reporting suboptimal care experiences is remarkable yet aligns with prior work, 81 , 82 , 83 and speaks to the notable accessibility gaps in LTSS. 84 It is notable that we observed striking variability in the geographic distribution of medical resources and practice patterns. Their effects on care quality and outcomes have been well established, 59 but the role of place in LTSS is more complex and less understood. Prior studies have primarily focused on place‐based differences in institutional care 85 or the state‐level service delivery and policy context. 45 , 70 Our findings reinforce the important but nuanced role of state and community‐level LTSS policies such as availability of paid family leave, Medicaid program structure, and efforts to better support direct care workers’ economic well‐being.

The strong and consistent association between neighborhood markers of social and economic deprivation and adverse consequences due to unmet care needs found in this study reinforces the importance of social and public policies in late life. 86 The unequal and more pronounced prevalence of disability among low‐income and minoritized older adults 87 may compound financial accessibility and gaps in care quality. 20 , 88 Prior work demonstrates that family and unpaid caregivers to racially and ethnically minoritized older adults provide higher levels of care with more limited financial resources. 77 Addressing family and neighborhood social and economic well‐being is not without challenges and requires extended financial commitments and time for neighborhood effects on health to emerge. 89 Still, our findings point to potential target populations that might benefit from interventions. For example, interventions might follow the example set by Community Aging in Place—Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE), a behavioral intervention that specifically targets lower‐income older adults living with disability with a goal of independence at home, with demonstrated benefits for quality of life and function. 90

Our framework provides a starting place for understanding how place‐based policies, practices, and investments contribute to dimensions of LTSS care experiences. Although our study does not speak to causal pathways, findings reinforce the relevance of state and local strategies that invest in HCBS such as MLTSS, paid family leave, and paying direct care workers a living wage. We examine measures that may provide greater context to what is currently understood about older LTSS users’ care experiences through current instruments, such as the National Core Indicators – Aging and Disability (NCI‐AD). Although the NCI‐AD collects data on outcomes such as community participation, well‐being, and routine daily activities, findings are limited to a select number of participating states and do not account for geographic characteristics. 91 In addition to the NCI‐AD, states have used a variety of measures to evaluate LTSS quality, but most data collection efforts by states are administered to a small sample of beneficiaries and are not poised to facilitate a broader understanding across geographies. The utility of the framework that we put forth is in its ability to fill the gap in examining LTSS‐related quality nationally as well as being able to link self‐reported experiences to policy‐relevant measures. The framework also contributes evidence to arguments for improving LTSS through strategies such as state availability of paid family leave, paid sick leave, or MLTSS, which have yet to be established nationwide. 92 , 93 , 94 Our findings also underscore the growing interest in supporting the direct care workforce that delivers care to older adults in the community—lower state minimum wage and direct care worker wages were associated with an increased risk of experiencing participation restrictions. This further emphasizes the need for policymakers and providers to focus on increasing compensation for direct care work, as has been done in demonstrations that improve career trajectories for workers through training, certification, and increased mentorship and pay. 95 , 96

More research is needed to understand the implications of relationships between LTSS‐relevant characteristics and care experiences among members of key populations. Much of what is currently known and understood about the disparate experiences of racial and ethnic minoritized groups, dual enrollees, and those living with dementia is limited to smaller samples in specific geographic areas. Existent evidence demonstrates relationships between neighborhood characteristics, race, and health outcomes and health care access and quality, with racial and ethnic minoritized populations and dual enrollees fairing worse than their counterparts. 20 , 97 Additionally, greater neighborhood disadvantage has been shown to be associated with dementia neuropathology, 98 although findings related to the experiences of older adults living with dementia across different geographies are scant. Some states offer dementia‐specific services as part of their HCBS waivers (e.g., dementia coaching) that might impact care experiences of persons living with dementia, 99 These policies are worth examining as part of the LTSS environment in the future. Our framework also provides motivation to examine the impact of broader community and state‐level factors as they relate to key population members. Future studies should also consider the implications for rural populations as well as sexual and gender minoritized groups, for which there is a growing body of literature as it relates to experiences across long‐term care settings. 27 , 100 , 101 Further, future interventions should include considerations for the diverse needs that exist among older adults, with a lens toward improving equity in access to LTSS and subsequent care quality and quality of life outcomes.

We acknowledge several limitations. This is a cross‐sectional study, and we are unable to assess causality in observed relationships. We focus on selected measures within each of the LTSS‐relevant environmental domains, and those measures that are included may fail to capture key aspects of the state and local service delivery environment, such as local funding for in‐home services. Developing an LTSS environment framework also revealed areas for improvement in data collection. In addition to recommending more concerted efforts to obtain data about key populations, more information is needed about the built and natural environment, for which data are not as easily accessible as social and economic and health care services measures. Future research should also consider the scope of practice as it relates to the direct care workforce. Our framework provides opportunities for potential partnerships among researchers, advocacy organizations, providers, LTSS stakeholders, and policymakers to build data infrastructures, conduct program and policy evaluations related to LTSS, and disseminate actionable recommendations to improve care delivery and care quality for older adults living with disability. More work is needed to better understand the nuances of specific policies, which extend beyond the scope of the present study. Additionally, our analysis was not structured to comparatively assess the importance of specific levels of the societal, community, or household environment, and measures of social and economic factors encompassed the community level, whereas health care and social service delivery measures were predominately focused on the state level. However, our study is the first to link LTSS‐relevant environment characteristics and older adult care experiences using national data and has important implications for LTSS policy and practice in expanding our limited understanding of how contextual factors affect long‐term care delivery end points beyond those derived from administrative claims. Study findings present opportunities for next steps that move toward more comprehensive analyses that would draw on multiple levels. Additionally, although our study provides a framework useful for examining LTSS access and quality, data preceded the COVID‐19 pandemic, which exacerbated disparities for the most vulnerable populations. 102 The COVID‐19 pandemic intensified existing problems, such as the ongoing direct care workforce shortage that threatens care quality and continuity. 103 Future work examining the role of the LTSS environment in pandemic‐related challenges may identify modifiable factors or target areas for intervention to improve care delivery.

In conclusion, the present study introduces a novel framework to conceptualize LTSS‐relevant environmental characteristics and demonstrates its utility by quantitatively examining relationships between environmental context and person‐reported care experiences among community‐living older adults with disability. Our hope is that the framework may serve as a platform for further refinement and investigations to advance our knowledge of the pathways by which the LTSS environmental context shapes the care experiences of individuals living with disabilities. With recent efforts devoted to better understand social determinants of health, and the push for family‐friendly policies, findings provide direction for future research as well as policy and practice that will strengthen LTSS and improve quality of life for older adults with disabilities.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funds to support this work were provided by the National Institute on Aging IMbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and AD‐Related Dementias Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory (U54AG063546), the Johns Hopkins University Alzheimer's Disease Resource Center for Minority Aging Research (P30AG059298; to C.D.F.), the Hopkins Economics of Alzheimer's Disease and Services Center under award number P30AG066587 (to C.D.F., S.M.O., and J.L.W.), award number R35AG072310 (to C.D.F., J.G.B., and J.L.W.), award number T32AG066576 (to S.M.O.), and the National Institute of Minority Health Disparities through the Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions under award number U54MD000214 (to C.D.F.).

Appendix Table 1.

LTSS Environmental Characteristics and Care Experiences of Community‐Living Racially and Ethnically Minoritized Groups a with Disabilities b

| Adverse Consequences | Participation Restrictions | Subjective Well‐Being c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | No | Yes | p | High | Low | p | |

| Weighted estimate | 1,792,473 | 1,237,623 | 1,851,322 | 1,178,774 | 462,127 | 1,669,227 | |||

| % (unweighted n) | 59.2 (568) | 40.8 (397) | 61.1 (551) | 38.9 (396) | 21.7 (138) | 78.3 (547) | |||

| Social and Economic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood poverty | |||||||||

| T1 (<9.5%) | 62.0 (97) | 38.0 (62) | 0.10 | 63.4 (100) | 36.6 (59) | 0.63 | 14.3 (15) | 85.7 (82) | 0.02 |

| T2 (9.5% ‐ 18.9%) | 66.1 (163) | 33.9 (87) | 58.2 (141) | 41.8 (109) | 31.5 (50) | 68.5 (130) | |||

| T3 (> = 19.0%) | 54.1 (308) | 45.9 (230) | 61.8 (310) | 38.2 (228) | 19.1 (73) | 80.9 (335) | |||

| Neighborhood unemployment | |||||||||

| T1 (<6.3%) | 60.3 (96) | 39.7 (51) | 0.67 | 56.8 (87) | 43.2 (60) | 0.42 | 15.0 (19) | 85.0 (78) | 0.12 |

| T2 (6.3% ‐ 10.7%) | 62.1 (174) | 37.9 (110) | 64.5 (164) | 35.5 (120) | 27.5 (44) | 75.5 (172) | |||

| T3 (> = 10.8) | 56.6 (298) | 43.4 (218) | 60.5 (300) | 39.5 (216) | 19.9 (75) | 80.1 (297) | |||

| Neighborhood receipt of public assistance | |||||||||

| T1 (<19.0%) | 61.8 (102) | 38.2 (59) | 0.43 | 64.9 (105) | 35.1 (56) | 0.53 | 10.3 (14) | 89.7 (82) | <0.01 |

| T2 (19.0% ‐ 41.6%) | 62.2 (172) | 37.8 (104) | 58.2 (154) | 41.8 (122) | 31.8 (50) | 68.2 (141) | |||

| T3 (> = 41.7%) | 55.7 (294) | 44.3 (216) | 61.4 (292) | 38.6 (218) | 18.7 (74) | 81.3 (324) | |||

| Neighborhood social cohesion | |||||||||

| Low | 47.1 (114) | 52.9 (106) | <0.001 | 53.4 (116) | 46.6 (104) | 0.05 | 16.9 (29) | 83.1 (132) | 0.09 |

| High | 63.6 (454) | 36.4 (273) | 63.9 (435) | 36.1 (292) | 23.6 (109) | 76.4 (415) | |||

| Health Care and Social Service Delivery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid HCBS Generosity | |||||||||

| T1 (< 29.6%) | 60.3 (240) | 39.7 (153) | 0.85 | 55.1 (207) | 44.9 (186) | 0.11 | 16.7 (49) | 83.3 (243) | 0.11 |

| T2 (29.6% ‐ 42.3 %) | 57.2 (172) | 42.8 (122) | 60.7 (182) | 39.3 (112) | 29.5 (55) | 70.5 (169) | |||

| T3 (>42.3%) | 59.5 (156) | 40.5 (104) | 66.5 (162) | 33.5 (98) | 20.8 (34) | 79.2 (135) | |||

| State MLTSS | |||||||||

| Yes | 58.5 (363) | 41.5 (251) | 0.62 | 66.2 (374) | 33.8 (240) | <0.001 | 22.4 (95) | 77.6 (348) | 0.62 |

| No | 61.0 (205) | 39.0 (128) | 47.5 (177) | 52.5 (156) | 19.6 (43) | 80.4 (199) | |||

| State Minimum Wage | |||||||||

| At Federal Minimum | 54.7 (228) | 45.3 (155) | 0.24 | 57.5 (209) | 42.5 (174) | 0.18 | 15.6 (53) | 84.4 (231) | 0.02 |

| Above Federal Minimum | 61.2 (340) | 38.8 (224) | 62.8 (342) | 37.2 (222) | 24.8 (85) | 75.2 (316) | |||

| State percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who are Medicare Advantage enrollees | |||||||||

| T1 (<29%) | 57.3 (171) | 42.7 (135) | 0.53 | 51.5 (170) | 48.5 (136) | 0.01 | 77.0 (177) | 23.0 (48) | 0.52 |

| T2 (29% ‐ 38%) | 58.8 (313) | 41.2 (196) | 64.1 (299) | 35.9 (210) | 77.4 (284) | 22.6 (76) | |||

| T3 (> = 38%) | 63.7 (84) | 36.3 (48) | 64.6 (82) | 35.4 (50) | 83.9 (86) | 16.1 (14) | |||

| State percentage of residents who are Medicaid enrolled | |||||||||

| T1 (<18.4%) | 57.2 (166) | 42.8 (120) | 0.83 | 57.0 (156) | 43.0 (130) | 0.24 | 80.6 (172) | 19.4 (40) | 0.84 |

| T2 (18.4% ‐ 20.8%) | 58.7 (189) | 41.3 (126) | 59.5 (188) | 40.5 (127) | 77.4 (186) | 22.6 (54) | |||

| T3 (> = 20.8%) | 60.7 (213) | 39.3 (133) | 64.9 (207) | 35.1 (139) | 77.5 (189) | 22.5 (44) | |||

| State paid family leave | |||||||||

| Yes | 61.8 (105) | 38.2 (67) | 0.60 | 70.4 (107) | 29.6 (65) | 0.01 | 21.3 (23) | 78.7 (88) | 0.94 |

| No | 58.2 (463) | 41.8 (312) | 57.8 (444) | 42.2 (331) | 21.8 (115) | 78.2 (459) | |||

| State paid sick leave | |||||||||

| Yes | 61.6 (99) | 38.4 (64) | 0.65 | 72.2 (106) | 27.8 (57) | <0.01 | 21.9 (20) | 78.1 (81) | 0.97 |

| No | 58.4 (469) | 41.6 (315) | 57.5 (445) | 42.5 (339) | 21.6 (118) | 78.4 (466) | |||

| State Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act | |||||||||

| Yes | 58.5 (250) | 41.5 (172) | 0.73 | 63.6 (260) | 36.4 (162) | 0.23 | 76.1 (234) | 23.1 (65) | 0.29 |

| No | 60.1 (318) | 39.9 (207) | 57.8 (291) | 42.2 (234) | 81.3 (313) | 18.7 (73) | |||

| State No Wrong Door Score | |||||||||

| T1 (<50%) | 59.4 (158) | 40.6 (109) | 0.76 | 66.5 (240) | 33.5 (154) | 0.04 | 74.6 (221) | 25.4 (64) | 0.13 |

| T2 (50% ‐ 79%) | 60.7 (173) | 39.3 (108) | 57.4 (169) | 42.6 (139) | 85.0 (184) | 15.0 (38) | |||

| T3 (> = 79%) | 58.2 (237) | 41.8 (162) | 55.8 (142) | 44.2 (103) | 77.7 (142) | 22.3 (36) | |||

| Direct care worker mean hourly wages | |||||||||

| T1 (<$10.29) | 54.0 (218) | 46.0 (159) | 0.30 | 54.1 (196) | 45.9 (181) | 0.13 | 15.0 (52) | 85.0 (229) | 0.08 |

| T2 ($10.29‐ $11.26) | 60.1 (198) | 39.9 (128) | 63.7 (203) | 36.3 (123) | 27.2 (54) | 72.8 (185) | |||

| T3 ($11.26‐ $14.69) | 63.1 (152) | 36.9 (92) | 64.9 (152) | 35.1 (92) | 22.4 (32) | 77.6 (133) | |||

| Medicare reimbursement per beneficiary | |||||||||

| T1 (<$9,139.80) | 54.5 (108) | 45.5 (79) | 0.34 | 43.6 (98) | 56.4 (89) | <0.001 | 20.0 (31) | 80.0 (114) | 0.70 |

| T2 ($9,139.80‐ $9,998.37) | 56.3 (175) | 43.7 (130) | 64.9 (178) | 35.1 (127) | 19.4 (39) | 80.6 (178) | |||

| T3 (>$9,998.37) | 62.3 (285) | 37.7 (170) | 64.8 (275) | 35.2 (180) | 23.5 (68) | 76.5 (255) | |||

| Built and Natural Physical Environment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of state coordination council | |||||||||

| Yes | 62.0 (197) | 38.0 (121) | 0.29 | 49.4 (164) | 50.6 (154) | <0.001 | 16.9 (38) | 83.1 (199) | 0.17 |

| No | 57.8 (371) | 42.2 (258) | 66.7 (387) | 33.3 (242) | 23.9 (100) | 76.1 (348) | |||

| Presence of state web accessibility laws | |||||||||

| Yes | 58.8 (500) | 41.2 (346) | 0.53 | 63.2 (501) | 36.8 (345) | <0.01 | 21.4 (117) | 78.6 (487) | 0.57 |

| No | 63.0 (68) | 37.0 (33) | 38.7 (50) | 61.3 (51) | 25.3 (21) | 74.7 (60) | |||

| Neighborhood broadband access | |||||||||

| T1 (<74.2%) | 55.3 (281) | 44.7 (207) | 0.17 | 61.3 (280) | 38.7 (208) | 0.95 | 22.8 (74) | 77.2 (306) | 0.70 |

| T2 (74.2% ‐ 85.7%) | 64.6 (161) | 35.4 (96) | 61.5 (147) | 38.5 (110) | 22.3 (38) | 77.7 (136) | |||

| T3 (> = 85.8%) | 58.7 (126) | 41.3 (76) | 60.1 (124) | 39.9 (78) | 18.3 (26) | 81.7 (105) | |||

| Mean household to income ratio | |||||||||

| T1 (<0.03) | 54.8 (189) | 45.2 (148) | 0.41 | 56.1 (188) | 43.9 (149) | 0.20 | 16.9 (49) | 83.1 (208) | 0.171 |

| T2 (0.30 – 0.42) | 62,5 (191) | 37.5 (113) | 61.6 (177) | 38.4 (127) | 19.6 (46) | 80.4 (176) | |||

| T3 (> = 0.43) | 60.5 (180) | 39,5 (112) | 64.9 (177) | 35.1 (115) | 27.3 (41) | 72.7 (154) | |||

| Mean neighborhood housing age | |||||||||

| T1 (<1966) | 60.2 (256) | 39.8 (170) | 0.71 | 64.8 (260) | 35.2 (166) | 0.39 | 27.2 (66) | 72.8 (238) | 0.11 |

| T2 (1966‐1980) | 56.5 (162) | 43.5 (111) | 57.8 (147) | 42.2 (126) | 19.4 (39) | 80.6 (163) | |||

| T3 (> = 1981) | 59.6 (146) | 40.4 (97) | 58.4 (139) | 41.6 (104) | 16.4 (33) | 83.6 (143) | |||

| Any housing quality issues | |||||||||

| Yes | 57.7 (132) | 42.3 (92) | 0.72 | 63.8 (137) | 36.2 (87) | 0.49 | 18.6 (34) | 81.4 (146) | 0.38 |

| No | 59.5 (436) | 40.5 (287) | 60.4 (414) | 39.6 (309) | 22.7 (104) | 77.3 (401) | |||

Note . 947 NHATS 2015 adults aged 65 or older who receive assistance with routine household, self‐care, or mobility activities and live‐in traditional community settings or residential care settings.

Racially and ethnically minoritized groups include Non‐Hispanic Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or other.

To protect against disclosure, statistics must be based on a minimum number of cases. Estimates are not reported when too few cases are in the sample. Disclosure protection protocols do not allow the reporting of the minimum cell threshold nor specific table cells that contain too few cases.

Sample excludes 187 NHATS respondents where proxy person provided responses.

Appendix Table 2.

LTSS Environmental Characteristics and Care Experiences of Community‐Living Medicaid‐Enrolled Older Adults a

| Adverse Consequences | Participation Restrictions | Subjective Well‐Being b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | No | Yes | p | High | Low | p | |

| Weighted estimate | 1,250,552 | 1,032,984 | 1,379,263 | 904,273 | 252.039 | 1,554,640 | |||

| % (unweighted n) | 54.8 (316) | 45.2 (263) | 60.4 (326) | 39.6 (253) | 14.0 (67) | 86.0 (377) | |||

| Social and Economic | |||||||||

| Neighborhood poverty | |||||||||

| <19.0% | 59.4 (140) | 40.6 (107) | 0.08 | 58.0 (135) | 42.0 (112) | 0.40 | 15.0 (32) | 85.0 (145) | 0.69 |

| > = 19.0% | 50.3 (176) | 49.7 (156) | 62.7 (191) | 37.3 (141) | 13.0 (35) | 87.0 (232) | |||

| Neighborhood unemployment | |||||||||

| <10.8% | 57.2 (166) | 42.8 (127) | 0.33 | 59.5 (164) | 40.5 (129) | 0.68 | 14.4 (34) | 85.6 (193) | 0.74 |

| > = 10.8% | 51.5 (150) | 48.5 (136) | 61.6 (162) | 38.4 (124) | 13.3 (33) | 86.7 (184) | |||

| Neighborhood receipt of public assistance | |||||||||

| Below the 50th percentile (<30.5%) | 59.8 (98) | 40.2 (69) | 0.14 | 58.7 (98) | 41.3 (69) | 0.65 | 11.9 (18) | 88.1 (103) | 0.50 |

| At or above the 50th percentile (> = 30.5%) | 52.0 (218) | 48.0 (194) | 61.3 (228) | 38.7 (184) | 15.0 (49) | 85.0 (274) | |||

| Health Care and Social Service Delivery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid HCBS Generosity | |||||||||

| T1 (< 29.6%) | 57.9 (135) | 42.1 (94) | 0.69 | 57.7 (123) | 42.3 (106) | 0.61 | 14.1 (25) | 85.9 (151) | 0.99 |

| T2 (29.6% ‐ 42.3 %) | 52.5 (89) | 47.5 (92) | 60.3 (103) | 39.7 (78) | 14.1 (21) | 85.9 (129) | |||

| T3 (>42.3%) | 53.6 (92) | 46.4 (77) | 63.0 (100) | 37.0 (69) | 13.7 (21) | 86.3 (97) | |||

| State MLTSS | |||||||||

| Yes | 55.7 (199) | 44.3 (163) | 0.54 | 62.8 (212) | 37.2 (150) | 0.10 | 16.2 (45) | 83.8 (223) | 0.11 |

| No | 52.8 (117) | 47.2 (100) | 55.3 (114) | 44.7 (103) | 9.7 (22) | 90.3 (154) | |||

| State Minimum Wage | |||||||||

| At Federal Minimum | 52.5 (132) | 47.5 (105) | 0.53 | 60.7 (136) | 39.3 (101) | 0.92 | 9.9 (27) | 90.1 (156) | 0.12 |

| Above Federal Minimum | 56.0 (184) | 44.0 (158) | 60.2 (190) | 39.8 (152) | 16.2 (40) | 83.8 (221) | |||

| State percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who are Medicare Advantage enrollees | |||||||||

| T1 (<29%) | 50.6 (81) | 49.4 (91) | 0.03 | 52.6 (90) | 47.4 (82) | 0.05 | 12.2 (21) | 87.8 (122) | 0.15 |

| T2 (29% ‐ 38%) | 51.8 (175) | 48.2 (139) | 61.6 (178) | 38.4 (136) | 12.0 (32) | 88.0 (198) | |||

| T3 (> = 38%) | 69.5 (60) | 30.5 (33) | 67.4 (58) | 32.6 (35) | 22.4 (14) | 77.6 (57) | |||

| State percentage of residents who are Medicaid enrolled | |||||||||

| T1 (<18.4%) | 49.4 (94) | 50.6 (89) | 0.07 | 54.6 (99) | 45.4 (84) | 0.11 | 88.5 (126) | 11.5 (21) | 0.64 |

| T2 (18.4% ‐ 20.8%) | 64.9 (108) | 35.1 (73) | 65.0 (106) | 35.0 (75) | 83.9 (120) | 16.1 (25) | |||

| T3 (> = 20.8%) | 51.7 (114) | 48.3 (101) | 61.9 (121) | 38.1 (94) | 85.6 (131) | 14.4 (21) | |||

| State paid sick leave | |||||||||

| Yes | 53.5 (56) | 46.5 (50) | 0.83 | 65.4 (60) | 34.6 (46) | 0.22 | 11.5 (12) | 88.5 (64) | 0.53 |

| No | 55.1 (260) | 44.9 (213) | 59.0 (266) | 41.0 (207) | 14.6 (55) | 85.4 (313) | |||

| State Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act | |||||||||

| Yes | 50.3 (132) | 49.7 (127) | 0.12 | 62.2 (151) | 37.8 (108) | 0.42 | 14.1 (29) | 85.9 (166) | 0.96 |

| No | 59.4 (184) | 40.6 (136) | 58.5 (175) | 41.5 (145) | 13.8 (38) | 86.2 (211) | |||

| State No Wrong Door Score | |||||||||

| T1 (<50%) | 49.8 (118) | 50.2 (112) | 0.01 | 62.7 (130) | 37.3 (100) | 0.68 | 15.9 (29) | 84.0 (146) | 0.31 |

| T2 (50% ‐ 79%) | 50.0 (106) | 50.0 (91) | 58.5 (112) | 41.5 (85) | 9.1 (18) | 91.0 (131) | |||

| T3 (> = 79%) | 66.8 (92) | 33.2 (60) | 59.1 (84) | 40.9 (68) | 16.2 (20) | 83.8 (100) | |||

| Mean hourly wages | |||||||||

| T1 (<$10.29) | 49.6 (126) | 50.4 (114) | 0.36 | 57.1 (129) | 42.9 (111) | 0.40 | 7.8 (23) | 92.2 (163) | 0.02 |

| T2 ($10.29‐ $11.26) | 56.2 (102) | 43.8 (87) | 60.5 (108) | 39.5 (81) | 20.8 (27) | 79.2 (119) | |||

| T3 ($11.26‐ $14.69) | 59.3 (88) | 40.7 (62) | 64.4 (89) | 35.6 (61) | 14.0 (17) | 86.0 (95) | |||

| Medicare reimbursement per beneficiary | |||||||||

| T1 (<$9,139.80) | 55.5 (71) | 44.5 (65) | 0.99 | 51.2 (73) | 48.8 (63) | 0.14 | 15.5 (19) | 84.5 (86) | 0.45 |

| T2 ($9,139.80‐ $9,998.37) | 54.8 (99) | 45.2 (87) | 64.2 (109) | 35.8 (77) | 10.3 (18) | 89.7 (127) | |||

| T3 (>$9,998.37) | 54.4 (146) | 45.6 (111) | 62.4 (144) | 37.6 (113) | 15.8 (30) | 84.2 (164) | |||

| Built and Natural Physical Environment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of state coordination council | |||||||||

| Yes | 63.1 (125) | 36.9 (78) | 0.04 | 57.4 (113) | 42.6 (90) | 0.37 | 16.1 (24) | 83.9 (131) | 0.49 |

| No | 50.8 (191) | 49.2 (185) | 61.8 (213) | 38.2 (163) | 13.0 (43) | 87.0 (246) | |||

| Neighborhood broadband access | |||||||||

| Below the 50th percentile (<80.5%) | 55.1 (222 | 44.9 (175) | 0.88 | 63.2 (231) | 36.8 (166) | 0.23 | 15.9 (51) | 84.1 (266) | 0.20 |

| At or above the 50th percentile (> = 80.5%) | 54.2 (94) | 45.8 (88) | 55.7 (95) | 44.3 (87) | 10.3 (16) | 89.7 (111) | |||

| Mean household value to income ratio | |||||||||

| T1 (<0.03) | 52.5 (98) | 47.5 (94) | 0.62 | 55.0 (103) | 45.0 (89) | 0.15 | 8.9 (19) | 91.1 (131) | 0.27 |

| T2 (0.30 – 0.42) | 58.4 (119) | 41.6 (85) | 60.7 (115) | 39.3 (89) | 15.0 (25) | 85.0 (136) | |||

| T3 (> = 0.43) | 53.8 (92) | 46.2 (79) | 65.9 (101) | 34.1 (70) | 17.7 (21) | 82.3 (102) | |||

| Mean neighborhood housing age | |||||||||

| T1 (<1966) | 57.4 (132) | 42.6 (110) | 0.57 | 64.3 (142) | 35.7 (100) | 0.38 | 17.8 (31) | 82.2 (156) | 0.26 |

| T2 (1966‐1980) | 51.5 (100) | 48.5 (88) | 56.2 (100) | 43.8 (88) | 11.7 (24) | 88.3 (121) | |||

| T3 (> = 1981) | 55.2 (84) | 44.8 (65) | 60.3 (84) | 39.7 (65) | 11.3 (12) | 88.7 (100) | |||

| Any housing quality issues | |||||||||

| Yes | 46.9 (70) | 53.1 (72) | 0.12 | 62.6 (79) | 37.4 (63) | 0.68 | 11.1 (11) | 88.9 (103) | 0.46 |

| No | 56.9 (246) | 43.1 (191) | 59.8 (247) | 40.2 (190) | 14.8 (56) | 85.2 (274) | |||

Note . 579 NHATS 2015 adults aged 65 or older who receive assistance with routine household, self‐care, or mobility activities and live‐in traditional community settings or residential care settings.

To protect against disclosure, statistics must be based on a minimum number of cases. Estimates are not reported when too few cases are in the sample. Disclosure protection protocols do not allow the reporting of the minimum cell threshold nor specific table cells that contain too few cases. Categories are combined when at all possible

Sample excludes 120 NHATS respondents where proxy person provided responses.

Appendix Table 3.

LTSS Environmental Characteristics and Care Experiences of Community‐Living Older Adults with Dementiaa

| Adverse Consequences | Participation Restrictions | Subjective Well‐Being | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | No | Yes | p | ||||

| Weighted estimate | 1,381,747 | 1,057,598 | 1,482,081 | 957,261 | |||||

| % (unweighted n) | 56.6 (375) | 43.4 (283) | 60.8 (401) | 39.2 (257) | |||||

| Social and Economic | |||||||||

| Neighborhood poverty | |||||||||

| T1 (<9.5%) | 60.4 (124) | 39.6 (83) | 0.33 | 59.2 (126) | 40.8 (81) | 0.78 | |||

| T2 (9.5% ‐ 18.9%) | 56.1 (129) | 43.9 (93) | 60.4 (131) | 39.6 (91) | |||||

| T3 (> = 19.0%) | 52.1 (122) | 47.9 (107) | 63.4 (144) | 36.6 (85) | |||||

| Neighborhood unemployment | |||||||||

| T1 (<6.3%) | 62.4 (130) | 37.6 (77) | 0.17 | 54.7 (123) | 45.3 (84) | 0.14 | |||

| T2 (6.3% ‐ 10.7%) | 54.1 (112) | 45.9 (91) | 61.6 (118) | 38.4 (85) | |||||

| T3 (> = 10.8) | 52.7 (133) | 47.3 (115) | 66.7 (160) | 33.3 (88) | |||||

| Neighborhood receipt of public assistance | |||||||||

| T1 (<19.0%) | 60.5 (137) | 39.5 (90) | 0.21 | 62.2 (143) | 37.8 (84) | 0.58 | |||

| T2 (19.0% ‐ 41.6%) | 57.0 (124) | 43.0 (85) | 57.4 (121) | 42.6 (88) | |||||

| T3 (> = 41.7%) | 49.9 (113) | 50.1 (108) | 62.9 (137) | 37.1 (84) | |||||

| Neighborhood social cohesion | |||||||||

| Low | 53.9 (73) | 46.1 (61) | 0.52 | 58.1 (75) | 41.9 (59) | 0.54 | |||

| High | 57.4 (302) | 42.6 (222) | 61.5 (326) | 38.5 (198) | |||||

| Health Care and Social Service Delivery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid HCBS Generosity | |||||||||

| T1 (< 29.6%) | 56.2 (135) | 43.8 (100) | 0.33 | 55.4 (130) | 44.6 (105) | 0.16 | |||

| T2 (29.6% ‐ 42.3 %) | 61.6 (111) | 38.4 (85) | 60.3 (122) | 39.7 (74) | |||||

| T3 (>42.3%) | 53.2 (129) | 46.8 (98) | 65.6 (149) | 34.4 (78) | |||||

| State MLTSS | |||||||||

| Yes | 54.9 (230) | 45.1 (185) | 0.31 | 62.4 (259) | 37.6 (156) | 0.36 | |||

| No | 59.9 (145) | 40.1 (98) | 57.7 (142) | 42.3 (101) | |||||

| State Minimum Wage | |||||||||

| At Federal Minimum | 54.3 (144) | 45.7 (115) | 0.48 | 55.6 (142) | 44.4 (117) | 0.10 | |||

| Above Federal Minimum | 57.8 (231) | 42.2 (168) | 63.4 (259) | 36.6 (140) | |||||

| State percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who are Medicare Advantage enrollees | |||||||||

| T1 (<29%) | 57.9 (103) | 42.1 (86) | 0.87 | 51.6 (104) | 48.4 (85) | <0.05 | |||

| T2 (29% ‐ 38%) | 55.5 (199) | 44.5 (148) | 61.7 (212) | 38.3 (135) | |||||

| T3 (> = 38%) | 58.1 (73) | 41.9 (49) | 69.1 (85) | 30.9 (37) | |||||

| State percentage of residents who are Medicaid enrolled | |||||||||

| T1 (<18.4%) | 57.9 (115) | 42.1 (79) | 0.30 | 51.7 (109) | 48.3 (85) | 0.04 | |||

| T2 (18.4% ‐ 20.8%) | 60.7 (128) | 39.3 (93) | 62.7 (135) | 37.3 (86) | |||||

| T3 (> = 20.8%) | 52.5 (132) | 47.5 (111) | 65.8 (157) | 34.2 (86) | |||||

| State paid family leave | |||||||||

| Yes | 51.2 (65) | 48.6 (55) | 0.29 | 66.7 (79) | 33.3 (41) | 0.21 | |||

| No | 58.1 (310) | 41.9 (228) | 59.1 (322) | 40.9 (216) | |||||

| State paid sick leave | |||||||||

| Yes | 53.4 (76) | 46.6 (62) | 0.51 | 71.2 (95) | 28.8 (43) | <0.01 | |||

| No | 57.7 (299) | 42.3 (221) | 57.4 (306) | 42.6 (214) | |||||

| State Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act | |||||||||

| Yes | 53.7 (164) | 46.3 (131) | 0.23 | 63.0 (190) | 37.0 (105) | 0.33 | |||

| No | 59.4 (211) | 40.6 (152) | 58.7 (211) | 41.3 (152) | |||||

| State No Wrong Door Score | |||||||||

| T1 (<50%) | 52.6 (134) | 47.4 (116) | 0.19 | 62.6 (156) | 37.4 (94) | 0.58 | |||

| T2 (50% ‐ 79%) | 55.7 (132) | 44.3 (99) | 57.2 (131) | 42.8 (100) | |||||

| T3 (> = 79%) | 62.9 (109) | 37.1 (68) | 62.4 (114) | 37.6 (63) | |||||

| Mean hourly wages | |||||||||

| T1 (<$10.29) | 51.8 (131) | 48.2 (112) | 0.37 | 53.0 (127) | 47.0 (116) | 0.03 | |||

| T2 ($10.29‐ $11.26) | 59.0 (131) | 41.0 (94) | 60.4 (143) | 39.6 (82) | |||||

| T3 ($11.26‐ $14.69) | 58.5 (113) | 41.5 (77) | 68.7 (131) | 31.3 (59) | |||||

| Medicare reimbursement per beneficiary | |||||||||

| T1 (<$9,139.80) | 59.7 (108) | 40.3 (69) | 0.35 | 60.3 (108) | 39.7 (69) | 0.94 | |||

| T2 ($9,139.80‐$9,998.37) | 59.0 (127) | 41.0 (97) | 60.2 (134) | 39.8 (90) | |||||

| T3 (>$9,998.37) | 52.9 (140) | 47.1 (117) | 61.5 (159) | 38.5 (98) | |||||

| Built and Natural Physical Environment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of state coordination council | |||||||||

| Yes | 58.7 (126) | 41.3 (86) | 0.52 | 58.3 (124) | 41.7 (88) | 0.43 | |||

| No | 55.6 (249) | 44.4 (197) | 61.9 (277) | 38.1 (169) | |||||

| Presence of state web accessibility laws | |||||||||

| Yes | 57.4 (332) | 42.6 (249) | 0.31 | 59.9 (349) | 40.1 (232) | 0.17 | |||

| No | 50.1 (43) | 49.9 (34) | 67.8 (52) | 32.2 (25) | |||||

| Neighborhood broadband access | |||||||||

| T1 (<74.2%) | 46.7 (110) | 53.3 (111) | 0.06 | 55.9 (128) | 44.1 (93) | 0.50 | |||

| T2 (74.2% ‐ 85.7%) | 61.2 (123) | 38.8 (81) | 62.8 (126) | 37.2 (78) | |||||

| T3 (> = 85.8%) | 58.8 (142) | 41.2 (91) | 62.0 (147) | 38.0 (86) | |||||

| Mean household value to income ratio | |||||||||

| T1 (<0.03) | 53.1 (115) | 46.9 (100) | 0.54 | 55.7 (119) | 44.3 (96) | 0.19 | |||

| T2 (0.30 – 0.42) | 60.2 (119) | 39.8 (85) | 58.6 (123) | 41.4 (81) | |||||

| T3 (> = 0.43) | 57.2 (139) | 42.8 (94) | 66.4 (156) | 33.6 (77) | |||||

| Mean neighborhood housing age | |||||||||

| T1 (<1966) | 57.8 (129) | 42.2 (97) | 0.81 | 64.2 (147) | 35.8 (79) | 0.46 | |||

| T2 (1966‐1980) | 54.2 (116) | 45.8 (89) | 60.9 (123) | 39.1 (82) | |||||

| T3 (> = 1981) | 57.1 (128) | 42.9 (97) | 57.1 (129) | 42.9 (96) | |||||

| Any housing quality issues | |||||||||

| Yes | 59.6 (54) | 40.4 (43) | 0.59 | 60.0 (60) | 40.0 (37) | 0.91 | |||

| No | 56.2 (321) | 43.8 (240) | 60.9 (341) | 39.1 (220) | |||||

| Residence type | |||||||||

| Traditional community | 55.8 (306) | 44.2 (236) | 0.49 | 60.0 (329) | 40.0 (213) | 0.57 | |||

| Residential care setting | 59.7 (69) | 40.3 (47) | 63.5 (72) | 36.5 (44) | |||||

Note. NHATS 2015 adults aged 65 or older who receive assistance with routine household, self‐care, or mobility activities and live‐in traditional community settings or residential care settings. To protect against disclosure, statistics must be based on a minimum number of cases. Estimates are not reported when too few cases arein the sample. Disclosure protection protocols do not allow the reporting of the minimum cell threshold nor specific table cells that contain too few cases.

References

- 1. Baltes PB, Smith J. New frontiers in the future of aging: from successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology. 2003;49(2):123‐135. 10.1159/000067946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Q. 2014;92(3):509‐541. 10.1111/1468-0009.12076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]