Abstract

Public health discipline and practice have prioritized work on poverty and populations at high risk for material deprivation, with less consideration for the full spectrum of financial circumstances relative to well-being. Public health can make a much-needed contribution to this area, which is currently dominated by the financial industry, focused on individual behaviors, and lacking the definitional consensus needed for research and evaluation. A population-level lens can reveal the social determinants and health consequences of real or perceived poor financial circumstances.

This article aims to improve conceptual understanding of financial circumstances among public health scholars and professionals. We identified concepts through a critical literature review of peer-reviewed and practice-based resources on financial well-being and financial strain. We developed a glossary of concepts related to financial circumstances and categorized concepts according to their level of influence using an approach informed by socioecological models. We provide a concept map that illustrates the relationships between concepts in the context of their levels of influence.

This article will help to advance an agenda on financial well-being promotion in public health research and practice. (Am J Public Health. 2024;114(1):79–89. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307449)

The health effects of financial circumstances (the state of one’s financial affairs) have not fully garnered the attention of public health researchers and practitioners. Financial circumstances, beyond poverty, dictate individuals’ and populations’ relative access to the necessities of life and intersect with other factors in shaping experiences of power and privilege that affect health. Yet, the limited public health research on financial circumstances starkly contrasts with the abundance of research on poverty and material deprivation with respect to health outcomes. Missing dialogue between experts in financial circumstance–related fields (e.g., financial inclusion, security) and public health may explain this knowledge gap.1 In addition, conceptual limitations1–3 and divergent concept operationalization for data analysis1,3–5 may have discouraged public health professionals from venturing into this arena, instead retaining a focus on poverty as the chronic financial circumstance in most urgent need of attention.

Contemporary public health policies and programs have mostly targeted populations experiencing or at high risk of poverty and severe material deprivation, which are typically determined through predefined cutoff points for individual or household income. Reducing the burden of poor financial circumstances among the most disadvantaged populations is an unquestionable priority. However, poverty and material deprivation must be understood—and intervened with—relative to impacts on population health over the life course rather than particular cut points for individuals at any moment in time to shift the population distribution of risk.6 Analysis of different aspects of financial circumstances over time may reveal that nuances matter to health and overall well-being.7 Thus, in addition to high-risk approaches, population-wide approaches are necessary to address the root causes of poor financial circumstances and shift population risk levels.

Despite the limited focus to date, financial circumstance–related concepts have recently started to be incorporated into public health scholarship and practice. Much of the scarce public health literature has explored the relationship between perceived or objective financial circumstances and perceived stress manifested through physiological or emotional arousal.8–10 Few studies have focused on how and to what extent concepts related to poor financial circumstances weaken physical,8,11–13 mental,8,14,15 and social health.8,16,17 Recently, Weida et al.1 innovatively presented financial health as a social determinant of health. This promising work signals the need for clarity on existing financial circumstance–related concepts, especially those relative to public health action on social determinants of health.

When researchers and professionals share a common understanding of terminology to inform research and intervention design, delivery, and evaluation, it can improve coordination of efforts and collective effects on population health. Dismantling the cacophony of current concepts to lay out a solid foundation based on a common language will facilitate communication and intelligibility among multiple public health actors and agencies in research, government, and community settings. Consequently, it will create a fertile space for coproduction of knowledge and advancement of the diverse fields working to improve people’s financial circumstances.

This study mobilizes our efforts toward advancing an agenda for promoting financial well-being in public health research and practice. It was a secondary study of a larger project that culminated in an international public health framework18 and guidebook of strategies and indicators19 to inform population-level initiatives for financial well-being promotion and financial strain reduction. That larger project employed multiple methods through which we systematically collected concepts and definitions related to financial circumstances.

First, we undertook a critical narrative literature review of theoretical articles and practice-based resources on concepts related to financial strain and financial well-being used in social sciences, economics, consumer research, and public health literatures. The practice-based search targeted institutions such as the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The purpose of that review was to clarify definitions of financial strain and financial well-being as foundations to the larger project. We created a preliminary list of concepts and definitions that informed the search strategies used in the other 2 methods.

Second was a systematic rapid review of peer-reviewed literature and practice-based resources on financial well-being and financial strain initiatives in high-income countries published between 2015 and 2020. This was combined with a critical realist analysis to determine the underlying generative mechanisms of financial strain and financial well-being initiatives.20,21 It included 39 peer-reviewed resources and 36 practice-based reports. Simultaneously, our third method was a targeted review of frameworks related to financial strain and financial well-being published in the academic and practice-based literature. Fourteen frameworks from areas such as social policy and marketing were fully assessed. A careful analysis of the included resources from the rapid review and the review of frameworks led to revision and expansion of the original list of concepts and definitions.

Building on that foundational work, this article aims to provide conceptual clarity on the current financial circumstance–related literature by specifically introducing the various concepts with definitions. We provide a map that depicts the conceptual relationships between terms and according to different levels of influence. Conceptual clarity will help to advance the public health debate on this area. Although a comprehensive discussion of the health effects and social determinants of financial circumstances is beyond this article’s scope, a brief overview is necessary to contextualize the glossary and concept map that follow.

LIFE EVENTS THAT MATTER TO HEALTH AND EQUITY

People’s perceived or objective financial circumstances vary across the life course22 because of expected or unexpected changes in life circumstances. Attending college or university, experiencing the death of the family’s primary income earner, having or adopting a child, and obtaining a loan for a home purchase are a few examples of life events that may negatively impact people’s financial circumstances.23 These negative impacts can be temporary or permanent and affect people’s lives and health, whether to a lesser or greater extent. Such events may directly or indirectly influence health-related behaviors, health status, morbidity, mortality, and quality of life over the short and the long term.8,11,12,24

Although feeling or being under financial pressure and having limited access to financial support are unavoidable life events for many, some populations are at higher risk for such experiences and have lower chances of a quick financial recovery. For example, low-income households, single-parent families, undocumented immigrants, and Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable to these adverse experiences.9,22 Population groups with intersecting disadvantaged identities (e.g., older African American women25 or socially isolated rural residents15) are also more vulnerable to negative health consequences of poor financial circumstances. The nefarious relationship between financial circumstances and health may intensify inequalities, entrapping some people in poverty and increasing health gaps. These relationships call for public health attention, particularly from a population-level perspective.

APPLYING A POPULATION-LEVEL LENS

Current work from consumer research, economics, and the financial industry provides a narrow view of individual and household financial circumstances that eclipses analyses of external factors such as housing crises, discriminatory hiring practices, and rising tuition costs.3,5,26 The use of such a narrow focus to inform policy, program, and service development and delivery is worrisome because it may unintentionally perpetuate systemic discrimination and stigma and entrench poverty and social and health inequities, especially among the most vulnerable.5 A population-level lens can instead unveil the external, negative forces that may drastically reduce the chances of people enjoying better financial circumstances in the present and future. It helps end the shaming of those who have financial struggles or are unable to build wealth as a result of their so-called lack of financial knowledge and skills or inadequate, unsustainable consumerism. A contextual perspective widens the domain of financial circumstances from the sphere of individual responsibility to collective responsibility.

The need for a population health approach that considers the full spectrum of financial circumstances relative to health and well-being confirms the much-needed contributions that public health can make in this arena. It can position the discussion of financial circumstances within neoliberal systems to uncover fundamental environmental (or population-level) and structural drivers such as economic recessions, financial speculation, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, socialization of economic losses vis-à-vis profit privatization, and debt crises.

A population health lens can thus support theoretical and causal analyses of pathways linking these drivers with financial circumstances and limited or no access to formal or semiformal financial products and services, which may exacerbate financial circumstance–related inequalities and health inequities. Application of a population health approach that considers socioecological and life course frameworks can widen practice-based and scholarly understanding, fostering analysis and inclusion of the myriad belief systems and modus operandi of different population groups relative to their financial resources. Such an understanding is critical for designing effective policies, programs, and services that address unmet basic needs and chronic socioeconomic disadvantage and, over the longer term, shifting risk factors for financial strain and financial well-being at population levels.

CONCEPTUALIZATION OF FINANCIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

Box 1 provides a glossary of single-level and multilevel concepts related to financial circumstances with definitions and by level of influence.4,10,22,24,26–45 We used a socioecological-informed approach to organize concepts according to their level of influence: individual (personal factors); psychosocial (perceptions and feelings relative to others); family, household, and community (social relationships); and environment (contextual factors). Here individual level concerns money management; psychosocial level refers to control and freedom of choice; family, household, and community level describes concepts of social dynamics and networks; and environment level comprises related infrastructure (e.g., financial services and products). As all multilevel concepts fall under the individual level, the terms are aligned with that concept heading. However, the definitions of the multilevel concepts cross multiple levels. A discussion of the definitions by level follows.

BOX 1—

Glossary of Single-Level and Multilevel Concepts Related to Financial Circumstances

| Concept | Definitions |

| Single-level concepts | |

| Individual level | |

| Financial empowerment | Acquisition of financial knowledge and skills to make responsible financial decisions,27,28 become financially stable, and be included in the financial system29 |

| Financial fragility | Individuals’ or households’ abilities to access emergency funds (e.g., savings, alternative credit system) to deal with an unexpected financial shock30,31 |

| Financial/economic/ material hardship | Disadvantageous financial circumstances experienced at the individual or household level10 according to objective measures32 |

| Financial literacy | Knowledge and skill development for sound financial decisions33,34 |

| Financial knowledge | Understanding of key financial terms and facts35,36,38 to support choice of financial services and products and financial planning37 |

| Financial situation | Objective facts of one’s financial circumstances (e.g., income, savings, debt management)22,38 |

| Financial skills | Ability to navigate financial systems and identify, process, and act on financial information (e.g., seeking and using financial advice)34–36,38 |

| Psychosocial level | |

| Financial attitudes | Positive or negative assessment of the value of proactive money management33 |

| Financial behaviors | Day-to-day money management actions36–38 |

| Financial happiness | Short-term feelings about one’s financial situation22 |

| Financial satisfaction | Long-term feelings about one’s financial situation22 |

| Financial (in)security | Positive feeling of being able to adapt and cope with adverse financial events (situated at the upper end of the financial resilience spectrum)39,40 |

| Financial self-efficacy | Confidence in one’s ability to reach financial goals, track money, and choose financial services and products33,34,41 |

| Financial strain | Feeling anxious or worried about inabilities to cope with financial hardships and make ends meet24 |

| Financial stress/vulnerability (often presented as synonymous with financial strain) | Feeling stressed or vulnerable about not being able to adapt to and cope with adverse financial events (situated at the lower end of the financial resilience spectrum)24,39,40 |

| Perceived financial well-being | Perception of current money management combined with sense of future financial security42 |

| Family, household, and community level | |

| Financial abuse | Control over of another person’s financial resources to the point that the victim loses access to financial information, disposable income, assets, and power to make financial decisions; becomes financially dependent on the perpetrator22,34; or becomes involved in financial fraud43 |

| Financial role | Position, responsibilities, and level of agency one may have in making financial decisions44 (e.g., decision-maker, dependent, contributor) |

| Financial social capital | One’s ability to rely on financial or in-kind support from relatives, neighbors, friends, and governments in times of financial adversity38,44 |

| Environment level | |

| Financial inclusion | Access to appropriate, accessible, and affordable formal, semiformal, or even informal financial services and products22,26 |

| Multilevel concepts: definitions | |

| Individual | Psychosocial |

| Financial well-being | State of being in which a person can meet current expenses and short- and long-term financial goals, has money left over to absorb financial shocks, has financial freedom (affording “wants”), and feels financially secure for present and future situations22,36,37,45 |

| Individual | Psychosocial/environment |

| Financial capability | Knowledge, skills, behaviors, attitudes, self-efficacy, and financial inclusion (access to appropriate financial services and products) for effective management of financial resources4,33,36 |

| Individual | Psychosocial/family, household, and community/environment |

| Financial health | Knowledge, skills, behaviors, financial situation, financial inclusion, and financial support from community allowing one to build resilience from financial setbacks and reach financial goals (e.g., paying off a student loan)44 |

| Financial resilience | Financial capability, financial inclusion, financial situation, and financial social capital shaping one’s ability to draw on internal capabilities and appropriate, acceptable, and accessible external resources to meet individual needs and preferences39 |

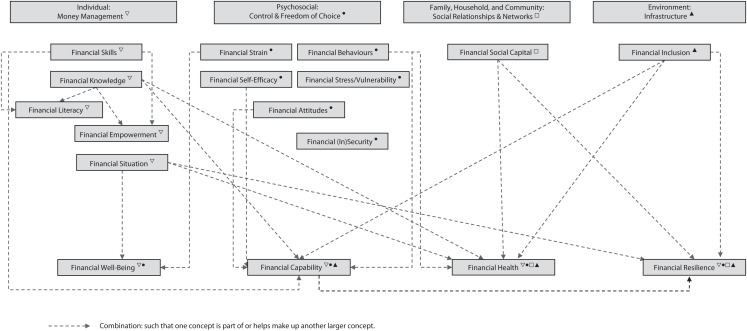

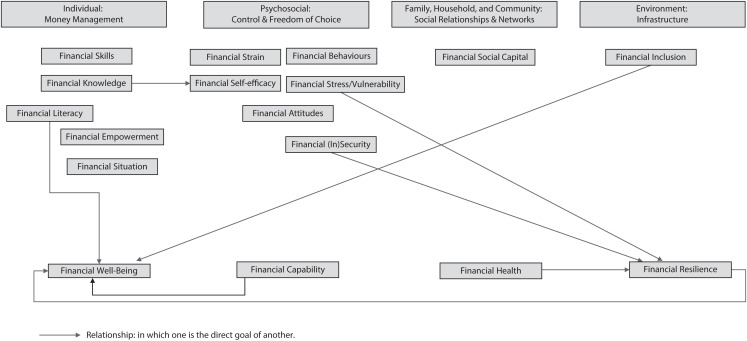

Figures 1 and 2 and Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) present and unpack a concept map depicting the conceptual relationships between the various financial circumstance–related terms that appear in the literature across several disciplines (e.g., consumer research, economics, social sciences). The dashed-line arrows in Figure 1 show what concepts are amalgamated by others. The concepts of financial knowledge and financial skills, for instance, are part of financial literacy.

FIGURE 1—

Concept Map Showing Combination of Concepts Into Overarching Constructs

Note. ▽ = individual: money management level; ● = psychosocial level; □ = family, household, and community level; ▲ = environment level.

FIGURE 2—

Concept Map Showing Concepts That Are Goals of Other Concepts

Some of the concepts presented in Figure 1 embrace more than 1 level (indicated by dashed-line arrows). Thus, different symbols represent the corresponding levels. For example, financial well-being comprises concepts from individual and psychosocial levels. The full-line arrows in Figure 2 indicate that 1 concept may be the goal of another. For example, financial well-being is envisioned as the goal of financial literacy, financial capability, financial resilience, and financial inclusion.22,41,46 Therefore, full-line arrows connect those latter concepts to the former. Figure A juxtaposes Figures 1 and 2 to illustrate the area’s conceptual complexity.

Individual Level: Money Management

Spending, saving, borrowing, and planning are cornerstone behaviors targeted by most financial circumstance–related work led by economists, financial education professionals, the financial services industry, consumer researchers, and government agencies. Their main concern is the (im)balance of income and assets and discretionary and nondiscretionary expenditures. Financial education emerges as a solution to improve one’s financial situation, alleviate poverty, and create “good financial citizens.”29 In response, public, private, and not-for-profit organizations offer financial education programs33,41 (e.g., financial coaching and counseling) predominantly to individuals.29

Extant criticisms on the concepts at this level decry their focus on people’s knowledge and skills as a mechanism for them to exert greater control over their own financial situation. This emphasis on optimal financial decision-making disregards both the contexts in which people live (including forces beyond their control, irrespective of their knowledge and skills) and their immediate needs (e.g., prioritizing rising daily costs over contributions to longer-term saving). Such concepts may be less meaningful in application and, worse, result in unintended harmful consequences for the poorest populations who are struggling with day-to-day survival.4 For instance, despite including the role of agency and adopting a less paternalistic approach, the concept of financial empowerment still places the onus of good financial circumstances primarily on the individual29 rather than targeting the intersectional structural and societal forces shaping the individual’s circumstances.

Psychosocial Level: Control and Freedom of Choice

At the psychosocial level are control and freedom of choice, which implicate the feelings of financial security. These concepts refer to perceptions of one’s financial situation and latitude in decision-making, indirectly implicating the role of agency, which is an individual’s feeling of control over taking actions that lead to particular effects. Research shows that perceived control and freedom to make financial decisions influence health independently of one’s objective financial circumstances.2 That is, feeling secure, happy, satisfied, confident, and less financially vulnerable or strained alongside financial attitudes and beliefs are distinct dimensions linked to financial circumstances. Exploring these subjective constructs may provide a unique interpretation of their effects on individual and population health and well-being, revealing varied patterns that are independent of objective measures of income and assets.

However, an overemphasis on perceptions of control and freedom of choice may result in oversight of the varied sociocultural, economic, and political factors that limit people’s abilities to control and make financial decisions.4,5 Thus, it is important to contextualize an individual’s perceptions and experiences of lack of control or limited freedom of choice relative to these system factors to illuminate potential causes of inequities when using subjective indicators of financial circumstances.

The debate on the importance of an individual’s freedom of choice clashes with the ideal of responsible financial choices. Although freedom of choice is important to financial circumstances at the individual level, that freedom seems to be allowed only for those who are not in debt or struggling to make ends meet. Freedom of choice seems to become attainable only when one has accumulated sufficient disposable resources through “optimal” behaviors and skills: only they could meritoriously enjoy latitude in decision-making without putting themselves at financial risk. This is problematic because it relates to a paternalistic view that does not give the opportunity for all people to choose to live the life they value.4

Family, Household, and Community Level: Social Relationships and Networks

At this level, concepts refer to the place people hold within a family, household, or community and their horizontal and vertical relationships with peers and institutions. For instance, people’s responses to financial well-being are dependent on the financial role they hold within a family (nuclear or extended) or household.44 The same responses may also shape individuals’ reliance on their social or cultural networks or on nonprofit or charitable organizations in their social or community networks that provide (formal or informal) support.

Shaped by power, cultural context, and identity, these social interactions are relevant to financial practices. The reason is that financial resources acquire intrinsic and symbolical values at the family, household, and community levels. Therefore, analysis of the social relationships and networks around financial circumstances can reveal the local cultures and values attributed to financial practices. This may shed light on psychosocial-level concepts by broadening understanding of why people believe, feel, and intend to act in certain ways.

Power dynamics, participation in social networks, and the strength of social connections may buffer the effects of financial hardships at this level; however, they may also restrict people’s abilities and freedom to access their own financial resources or make financial decisions. Negative relationships with family members, friends, acquaintances, or strangers may increase restrictions on individual financial freedom and expose disadvantaged individuals and populations to financial abuse through, for example, interception of their financial resources or coercion to be part of financial fraud. A further criticism of concepts at this level is the potential for problematic downloading of responsibility (by the government) for providing support onto nonprofit or charitable community organizations without also providing the resources for those agencies to adequately support people experiencing poor financial well-being.

Environment Level: Infrastructure

This level refers to the availability and quality of the environment to support people’s financial actions as currently described in related literature. The concept of financial inclusion refers directly to accessibility of financial services and products (mainly bank accounts, credit cards, and insurance) and indirectly to regulation of the financial industry.5 Financial inclusion has slowly evolved to include concepts related to inclusiveness, affordability, convenience, flexibility, acceptability, and safety.4 Although the financial industry often alludes to financial inclusion as a solution to individuals’ financial instability,29 this concept has been criticized for ignoring people’s needs, wants, and ways of being and doing.47 Instead of a user-centric focus, financial inclusion seems to be guided by a top-down approach with the ideal of a universal set of financial products and services that automatically would result in optimal financial behaviors and practices.4,5 Also missing from the financial inclusion concept is the context of financial industry deregulation, which expands profit-oriented banking strategies.48 This further excludes people from the formal financial system and aggravates inequalities in financial circumstances.

Multilevel Concepts

Some concepts used in the literature span different levels. For example, the definition of financial well-being encompasses both individual and psychosocial levels because it includes real and perceived aspects of financial circumstances: having the ability to meet regular expenses, having sufficient financial resources to buy “wants,” exerting control over finances, and feeling financially secure. These multilevel concepts are built on previous financial circumstance–related concepts and sometimes corresponding measures and indicators.44 They translate the progress of theoretical and empirical evidence in the field.

Notwithstanding the intrinsic strengths of the multifaced nature of these concepts, some limitations are present. For instance, the strength of the financial resilience concept is the recognition of contextual factors and inequities beyond one’s control.22 However, some criticisms refer to its emphasis on an individual’s adaptation even in scenarios of uncertainty and insecurity.5 As a concept, financial resiliency encompasses the expectation for individuals to learn new ways of consumption (e.g., reducing grocery costs by buying discount products or buying less or in bulk to combat rising grocery prices) rather than a socioeconomic systems approach to addressing costs in the supply chain.

DISCUSSION

We have introduced financial circumstance–related concepts from various disciplines and explained their interrelationships to increase understanding for public health action and research. Many concepts are intimately related and some multidimensional (Figures 1 and 2 and Figure A). The categorization of concepts by their level of influence builds public health’s capacity to broadly conceptualize and act on financial circumstances at a population level. Our categorization process maps the concepts to socioecological models (either explanatory or action oriented),49 which are popularly used for targeting health promotion actions.

Our concept map clearly shows the imbalance of financial circumstance–related concepts across levels, with most belonging to the individual and psychosocial levels. For instance, apart from financial inclusion, there are no other environment-level (or system) concepts accounting for the role of the financial sector or the influence of societal structures. In addition, as this area has begun to evolve, some concepts have been combined to create new terms, blending different definitions. Conceptual clarity is needed for effective measurement of and intervention on financial circumstances: without it, the relative impact of actions will be difficult to ascertain.

Public health can address theoretical gaps concerning environment-level influences to better conceptualize and measure financial circumstances. This will lead to a clearer analysis of intervention gaps and more effective population health interventions within and across the different “levels” implicated in financial well-being. Furthermore, public health scholarship and practice can expand their current horizons by ensuring that intersectional (e.g., power imbalances) and external structural (e.g., racial discrimination) factors are incorporated into emerging concepts and definitions.

Understanding the theoretical and applied relationships between concepts is critical to advancing public health action. This concept map and glossary can help public health professionals and scholars choose the most appropriate concepts for their practice or research questions. Our work offers a stepping stone for the analysis of underlying external drivers of financial circumstance–related constructs and the selection or development of measures and indicators accordingly. It also provides a foundation for a common, interdisciplinary understanding of financial circumstance–related concepts to advance intersectoral collaboration with professionals from other sectors. Interdisciplinary work could better reveal the big-picture system factors (e.g., inflation, income inequality, rising tuition, discriminatory and oppressive practices in banking institutions) that shape financial well-being. This would support the design of evidence-based, equitable interventions to address the drivers of poor financial circumstances.

Building such an evidence base may reveal the need for coordinative, system-level healthy public policies that strategically target proximal and distal determinants of poor financial circumstances. Multilevel concepts, although relatively underarticulated, may offer a more solid foundation for public health intervention and evaluation to explore nuanced associations with health outcomes and health inequities, which together drive decision-making. Recognizing its ethos and praxis, public health can make a substantive and innovative contribution to this field through deeper investigation of these complex, multidimensional concepts.

This article’s theoretical and practical contributions should be contextualized within its limitations. Our overview of concepts from various disciplines provides a glossary and relational concept map for those working with these terms; granular nuances of each concept were not captured. Despite the systematic process of gathering concepts and definitions through methods designed to develop public health resources on financial well-being and financial strain, the list of concepts included was not exhaustive. Our glossary may need to be expanded to include missed or emergent terms as the field evolves.

Furthermore, there are no generally acceptable definitions for many financial concepts.26,50 For example, Storchi and Johnson’s4 definition of financial capability involves wider social and cultural contexts beyond financial contexts. Another example is financial health, which has been used in the financial industry as a proxy equation for savings and spending.51 The lack of definitional and conceptual consensus may be partly due to efforts of researchers and practitioners to develop culturally grounded and context-specific definitions52 for particular uses, populations, or settings. Although important for addressing local needs, this can contribute to disagreement on standardized measures. Finally, some measures (e.g., those for financial well-being) are at an earlier stage of development than measures of financial knowledge or financial literacy.5,50

MOVING FORWARD

This article has addressed the current fragmented understanding of financial circumstance–related concepts by untangling a myriad of terms in use across several disciplines. We have presented them as separate constructs and illustrated their interrelationships. This is a much-needed first step toward improving conceptual clarity for using public and population health approaches to address entrenched poverty and other poor financial circumstances. Our article offers a more sophisticated understanding of financial circumstance–related terms, reveals critical conceptual gaps problematic for intervention and measurement, and presents a solid starting point for conceptual debate. It also contributes to an interdisciplinary discussion on the benefits of advancing a population-wide approach over (or alongside) a high-risk population-focused approach, shifting the focus from individuals to populations.

A population-level approach is urgently needed to address the root causes of poor financial circumstances and shift risk levels for the entire population. Grounded in systems thinking, a population-level approach would facilitate the analysis of higher-order structural and environmental factors to better reveal the societal forces and inequities that shape agency, power, and privilege: factors that pose significant barriers for disadvantaged individuals or groups to enjoy better financial circumstances.

As we have discussed elsewhere,7 individual- and household-level concepts related to financial circumstances require further advancement in public health scholarship and practice. Indeed, public health professionals are well positioned to offer a fresh perspective on the deleterious effects of financial circumstances on people’s lives, health, and well-being. Thanks to their training and experience in social determinants of health, health equity, life course approaches, socioecological models, and population health, public health professionals can support the transition from a limited interpretation of people’s financial circumstances to a broader contextualization in which people’s knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and decision-making are understood relative to distal social determinants, relative power, and structural inequities.

Future endeavors could integrate these concepts into public health and build a consensus on how to best measure financial circumstance–related concepts at individual, household, or population levels or combined levels. A consolidated list of indicators may further clarify the direction and dimension of the impact of financial circumstance–related concepts on health and support the development of more extensive analyses (see our related work on indicators as a starting point19). Moreover, use of a common set of indicators may result in a stronger evidence base indicating where interventions can achieve larger impacts on population health. Well-originated indicators beyond household income will facilitate exploration of causal links and associations between financial circumstances and health outcomes to drive action. Public health research and practice can play a critical role in advancing a global agenda on financial well-being promotion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the research staff members and scientists at the Centre for Healthy Communities (Canada) and Centre for Health Equity Training, Research and Evaluation (Australia) and the team at Alberta Health Services (Canada) who were involved in related projects on financial strain and financial well-being over the past five years, all of which inspired this work. More information about those projects can be found at healthiertogether.ca and https://www.ualberta.ca/public-health/research/centres/centre-for-healthy-communities/what-we-do/financial_wellbeing.html. The subproject described in this article used findings from a literature review that was conducted as part of an overarching project on financial well-being and financial strain funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weida EB, Phojanakong P, Patel F, Chilton M. Financial health as a measurable social determinant of health. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sehrawat K, Vij M, Talan G. Understanding the path toward financial well-being: evidence from India. Front Psychol. 2021;12:638408. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.638408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brüggen EC, Hogreve J, Holmlund M, Kabadayi S, Löfgren M. Financial well-being: a conceptualization and research agenda. J Bus Res. 2017;79: 228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storchi S, Johnson S.Financial capability for wellbeing: an alternative perspective from the capability approach. 2023. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/179371

- 5.Bowman D, Banks M, Fela G, Russell R, de Silva A.Understanding financial well-being in times of insecurity. 2023. http://library.bsl.org.au/jspui/bitstream/1/9423/1/Bowman_etal_Understanding_financial_wellbeing_2017.pdf

- 6.Rose G. Strategy of Preventive Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glenn NM, Nykiforuk CIJ. The time is now for public health to lead the way on addressing financial strain in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(6):984–987. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00430-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turunen E, Hiilamo H. Health effects of indebtedness: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):489. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okechukwu CA, El Ayadi AM, Tamers SL, Sabbath EL, Berkman L. Household food insufficiency, financial strain, work-family spillover, and depressive symptoms in the working class: the Work, Family, and Health Network study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):126–133. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park N, Heo W, Ruiz-Menjivar J, Grable JE. Financial hardship, social support, and perceived stress. Financ Couns Plan. 2017;28(2):322–332. doi: 10.1891/1052-3073.28.2.322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Costello TJ, et al. Financial strain and smoking cessation among racially/ethnically diverse smokers. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):702–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis CG, Mantler J. The Consequences of Financial Stress for Individuals, Families, and Society. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Centre for Research on Stress, Coping and Well-being, Carleton University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.White ND, Packard K, Kalkowski J. Financial education and coaching: a lifestyle medicine approach to addressing financial stress. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13(6):540–543. doi: 10.1177/1559827619865439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Whitfield K. Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank C, Davis CG, Elgar FJ. Financial strain, social capital, and perceived health during economic recession: a longitudinal survey in rural Canada. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2014;27(4):422–438. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.864389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afifi TD, Davis S, Merrill AF, Coveleski S, Denes A, Shahnazi AF. Couples’ communication about financial uncertainty following the great recession and its association with stress, mental health and divorce proneness. J Fam Econ Iss. 2018;39(2):205–219. doi: 10.1007/s10834-017-9560-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto AD, Da Ponte M, Bondy M, et al. Addressing financial strain through a peer-to-peer intervention in primary care. Fam Pract. 2020;37(6): 815–820. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmaa046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centre for Healthy Communities. Action-oriented public health framework on financial well-being and financial strain: executive summary. 2023. https://www.ualberta.ca/public-health/research/centres/centre-for-healthy-communities/ what-we-do/framework_eng_2022.pdf

- 19.Centre for Healthy Communities. Guidebook of strategies and indicators for action on financial well-being and financial strain: executive summary. 2023. https://www.ualberta.ca/public-health/research/centres/centre-for-healthy-communities/what-we-do/guidebook_eng_2022.pdf

- 20.Glenn NM, Yashadhana A, Jaques K, et al. The generative mechanisms of financial strain and financial well-being: a critical realist analysis of ideology and difference. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2023;12:6930. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yashadhana A, Glenn NM, Jaques K, et al. A rapid review of initiatives to address financial strain and wellbeing in high-income contexts. Public Health Res Pract. 2023;33(2):e3322315. doi: 10.17061/phrp3322315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muir K, Hamilton M, Noone JH, Marjolin A, Salignac F, Saunders P.Exploring financial well-being in the Australian context. 2023. https://assets.csi.edu.au/assets/research/Exploring-Financial-Wellbeing-in-the-Australian-Context-Report.pdf

- 23.Noone J, Muir K, Salignac F, et al. An Australian Framework for Financial Wellbeing. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.French D, Vigne S. The causes and consequences of household financial strain: a systematic review. Int Rev Financ Anal. 2019;62:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2018.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szanton SL, Allen JK, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Seeman T, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Effect of financial strain on mortality in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008; 63(6):S369–S374. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.S369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu J. Ability or opportunity to act: what shapes financial well-being? World Dev. 2020;128(104843) doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franz C. Financial empowerment and health related quality of life in Family Scholar House participants. J Financ Therapy. 2016;7(1) doi: 10.4148/1944-9771.1099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray JM, Mulholland E, Slade R.Financial counselling for people living on low incomes: international scan of best practices. 2023. https://prospercanada.org/getattachment/ea318ed1-9eb7-4ec5-85c8-adcc89e9cfda/Financial-Counselling-for-people-Living-on-Low-Inc.aspx

- 29.Loomis JM. Rescaling and reframing poverty: financial coaching and the pedagogical spaces of financial inclusion in Boston, Massachusetts. Geoforum. 2018;95:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. Canadians and their money: key findings from the 2019 Canadian Financial Capability Survey. 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/financial-consumer-agency/programs/research/canadian-financial-capability-survey-2019.html

- 31.Lusardi A, Schneider DJ, Tufano P.Financially fragile households: Evidence and implications. 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/financially-fragile-households-evidence-and-implications

- 32.Friedline T, Chen Z, Morrow S. Families’ Financial stress & well-being: the importance of the economy and economic environments. J Fam Econ Issues. 2021;42(suppl 1):34–51. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stuart G.What is financial capability? 2023. https://www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/what-is-financial-capability

- 34.Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. Financial literacy and retirement well-being in Canada: an analysis of the. Canadian Financial Capability Survey. 2014. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/fcac-acfc/documents/programs/research-surveys-studies-reports/financial-literacy-retirement-well-being.pdf

- 35.Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection. Measuring financial skills. 2023. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_financial-well-being_measuring-financial-skill_guide.pdf

- 36.Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Financial well-being: the goal of financial education. 2023. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_report_financial-well-being.pdf

- 37.Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. Financial well-being in Canada: survey results. 2023. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/fcac-acfc/documents/programs/research-surveys-studies-reports/financial-well-being-survey-results.pdf

- 38.Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection. Pathways to financial well-being: the role of financial capability. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_financial-well-being_pathways-role-financial-capability_research-brief.pdf

- 39.Muir K, Reeve R, Connolly C, Marjolin A, Salignac F, Ho K.Financial resilience in Australia 2015. 2023. https://www.nab.com.au/content/dam/nabrwd/documents/reports/financial/2015-financial-resilience.pdf

- 40.Weier M, Dolan K, Powell A, Muir K, Young A.Money stories: financial resilience among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. 2023. https://assets.csi.edu.au/assets/research/Indigenous-Financial-Resilience-Report.PDF

- 41.Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Effective financial education: five principles and how to use them. 2023. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/effective-financial-education-five-principles-and-how-use-them/c

- 42.Netemeyer RG, Warmath D, Fernandes D, Lynch JG., Jr How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. J Consum Res. 2018;45(1): 68–89. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucx109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Criminal Justice, Government of Canada. Elder abuse: financial fraud by strangers. 2022. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/fv-vf/eldfr-ainfr/eldfr-ainfr.html

- 44.Ladha T, Asrow K, Parker S, Rhyne E, Kelly S.Beyond financial inclusion: financial health as a global framework. 2023. https://www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/beyond-financial-inclusion-financial-health-as-a-global-framework

- 45.Salignac F, Hamilton M, Noone J, Marjolin A, Muir K. Conceptualizing financial wellbeing: an ecological life-course approach. J Happiness Stud. 2020;21(5):1581–1602. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00145-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. Review of financial literacy research in Canada: an environmental scan & gap analysis. 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/financial-consumer-agency/programs/research/review-financial-literacy-research.html

- 47.Harper A, Baker M, Edwards D, Herring Y, Staeheli M. Disabled, poor, and poorly served: access to and use of financial services by people with serious mental illness. Soc Serv Rev. 2018;92(2): 202–240. doi: 10.1086/697904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caplan MA, Birkenmaier J, Bae J. Financial exclusion in OECD countries: a scoping review. Int J Soc Welfare. 2021;30(1):58–71. doi: 10.1111/ijsw.12430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health. A review of frameworks on the determinants of health. 2023. https://nccdh.ca/images/uploads/comments/CCSDH_A-review-of-frameworks-on-the-determinants-of-health_EN.pdf

- 50.Kempson E, Poppe C.Understanding financial well-being and capability—a revised model and comprehensive analysis. 2023. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12199/5357

- 51.Innovations for Poverty Action. Nudges for financial health: global evidence for improved product design. 2023. https://www.poverty-action.org/publication/nudges-financial-health-global-evidence-improved-product-design

- 52.Abrantes-Braga FDM, Veludo-de-Oliveira T. Development and validation of financial well-being related scales. Int J Bank Marketing. 2019;37(4):1025–1040. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-03-2018-0074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]