Abstract

Background

Thoracic aortic dissection (TAD) is a severe and often lethal complication in people with hypertension. Current practice in the treatment of chronic type B aortic dissections is the use of beta‐blockers as first‐line therapy to decrease aortic wall stress. Other antihypertensive medications, such as calcium channel blockers (CCBs), angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), have been suggested for the medical therapy of type B TAD.

Objectives

To assess the effects of first‐line beta‐blockers compared with other first‐line antihypertensive drug classes for treating chronic type B TAD.

Search methods

We searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for related reviews. We searched the Hypertension Group Specialised Register (1946 to 26 January 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2014, Issue 1), MEDLINE (1946 to 24 January 2014), MEDLINE In‐Process, EMBASE (1974 to 24 January 2014) and ClinicalTrials.gov (to 26 January 2014).

Selection criteria

We considered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing different antihypertensive medications in the treatment of chronic type B TAD to be eligible for inclusion. Total mortality rate was the primary outcome of this review. Secondary outcomes included total non‐fatal adverse events relating to TADs and number of people not requiring surgical treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (KC, PL) independently reviewed titles and abstracts and decided on studies to include based on the inclusion criteria. We resolved discrepancies between the two review authors by discussion.

Main results

After a thorough review of the search results, we identified no studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Authors' conclusions

We did not find any RCTs that compared first‐line beta‐blockers with other first‐line antihypertensive medications for the treatment of chronic type B TAD. Therefore, there is no RCT evidence to support the current guidelines recommending the use of beta‐blockers. RCTs are required to assess the benefits and harms of beta‐blockers and other antihypertensive medications as first‐line treatment of chronic type B TAD.

Plain language summary

First‐line beta‐blockers versus other antihypertensive medications for chronic type B aortic dissection

Background

The aorta is the largest blood vessel in the body. It begins in the heart and provides oxygen to all parts of the body. Aortic dissection occurs when there is a tear in the inner wall of the aorta and bleeding occurs between the inner and outer walls of the blood vessel. It is a severe and often lethal complication. High blood pressure (hypertension) may be a key cause. Other risk factors may include connective tissue disorders, congenital vascular disease (abnormalities present at birth), aortitis (inflammation of the aortic wall), trauma or iatrogenic causes (problems resulting from medical treatment). Chronic type B aortic dissections are typically managed with medical therapy to reduce the stress on the aorta. Current practice guidelines suggest the use of beta‐blockers as a first‐line treatment.

Study characteristics

We searched scientific databases for randomized controlled trials (studies where people are randomly allocated to treated groups) comparing beta‐blockers versus other drugs used in the treatment of hypertension. The studies had to include people with thoracic aortic dissection of any cause that had not been treated with surgery. The evidence is current to January 2014.

Key results

We found no randomized controlled trials.

Quality of the evidence

As of January 2014, there is no evidence to show that beta‐blockers are superior to other antihypertensive medications as a first‐line treatment. Randomized control trials are needed to determine the best treatment of chronic type B aortic dissections.

Background

Thoracic aortic dissection (TAD) is a severe and often lethal complication in people with hypertension. While there are other aortic syndromes, such as aortic aneurysms or intramural hematomas, TADs are considered one of the most deadly aortic diseases with variable etiology and poor prognosis. In 1760, King George II of England was the first documented case of aortic dissection, diagnosed by autopsy (Nicholls 1761). Since then, advances in the diagnosis and treatment have significantly benefited people with this deadly condition.

Description of the condition

TADs result when there is hemorrhage into the medial layer of the aorta through a tear in the intima. The thoracic aorta is divided into multiple segments ‐ ascending aorta, transverse aortic arch and descending aorta. The ascending aorta begins distal to the aortic valves with the sinus of Valsalva and continues to the first branch of the aortic arch. The transverse aortic arch begins at the brachiocephalic artery and ends just distal to the left subclavian artery. Finally, the descending aorta starts beyond the left subclavian artery and continues to the point where it passes through the diaphragm.

Two classification systems have been commonly used in the literature to describe the location of the TAD. The DeBakey system classifies type I dissections as involvement of the entire thoracic aorta. Type II dissections involve only the ascending aorta. Type III dissections affect the descending aorta and may involve the abdominal aorta. The Stanford classification system simplifies the description to type A involving the ascending aorta and may involve the rest of the aorta; type B dissections involve the descending aorta and possibly the abdominal aorta, but strictly without involvement of the ascending aorta. In this systematic review, we have used the Stanford classification system.

Epidemiology of thoracic aortic dissection

It is believed that the number of TADs reported is an underestimate as many of these people die before ever reaching a medical facility. It is estimated that three to four cases of TAD occur in every 100,000 people per year and this is increasing, probably due to increased reported cases with improved recognition of symptoms and diagnostic imaging (LeMaire 2011). Studies have shown that the prevalence of type A dissections (52% to 67%) are more common than type B dissections (33% to 48%) (Chan 2014; LeMaire 2011). The mean age of onset is typically in the mid‐60s and TAD is twice as likely to occur in men than women, with women having an older mean age of onset of 67 years compared with 60 years in men (Chan 2014; Isselbacher 2007; LeMaire 2011).

TAD typically has a poor prognosis, dependent on the anatomical location, extent of the dissection, time between onset and diagnosis, and the treatment administered (LeMaire 2011). Type A dissections have the worst prognosis with an overall in‐hospital mortality of 30% (LeMaire 2011; Trimarchi 2010). It has been estimated that mortality rate increases by 1% for every hour after onset of symptoms if left untreated (Meszaros 2000). If only treated medically without surgical intervention, type A dissections have an in‐hospital mortality rate of 59% compared with 23% with surgical treatment (LeMaire 2011; Trimarchi 2010).

Type B dissections tend to have a better prognosis than type A dissections, having an overall in‐hospital mortality rate of 13% (Tsai 2006). With surgical intervention, the mortality rate of type B dissections is approximately 20%, given that complicated cases are treated surgically. Medical treatment has a mortality rate of approximately 10% (Tsai 2006).

Etiology and risk factors of thoracic aortic dissection

TADs may have many different underlying etiologies but there is one common theme to its pathogenesis. Weakening of the aortic walls is believed to be the key pathology leading to the actual dissection (Chan 2014; Chen 1997; Hiratzka 2010; Isselbacher 2007; LeMaire 2011; Nienaber 2003). Aortic dilation is believed to be one of the risk factors of TAD, with the risk of dissection significantly increasing when the ascending aorta dilates more than 6 cm and the descending aorta more than 7 cm (LeMaire 2011). However, dilation does not cause a TAD, but rather, it increases the risk of a TAD; a tear in the intimal wall is needed to initiate a TAD.

Hypertension has been analyzed extensively in TAD cases and has been well recognized to be one of the key causative factors of TAD (Chan 2014; Chen 1997; Hiratzka 2010; Isselbacher 2007; LeMaire 2011; Nienaber 2003). Chronic hypertension increases the force of systolic ejection jet against the aortic wall, which over time may weaken from continuous strain and eventually suffer from an intima tear. A sustained high blood pressure will propagate the false lumen within the walls of the aorta, hence forming the TAD.

Connective tissue disorders have been identified as a risk factor for TAD. These include genetic conditions such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys‐Dietz syndrome, Ehler‐Danlos syndrome and Turner syndrome. Congenital vascular diseases, such as bicuspid aortic valve and coarctation of the aorta, have also been identified as risk factors for TAD. Any form of aortitis can increase the risk of TAD, such as giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis, Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematous or syphilis. Other risk factors include trauma, iatrogenic causes from catheter interventions or valvular/aortic surgery, cocaine use and pregnancy (Chen 1997; Hiratzka 2010; Isselbacher 2007; LeMaire 2011; Nienaber 2003).

Description of the intervention

Surgical intervention is usually the recommended therapy for type A dissections due to the poor prognosis if left untreated (LeMaire 2011). Type B dissections have a significantly better prognosis and have different treatment options. Uncomplicated type B aortic dissections can be managed with medical therapy. Initial management of aortic dissection with antihypertensive medications decreases the aortic wall shear stress. Aortic wall stress is affected by the velocity of ventricular contraction, rate of ventricular contraction and blood pressure. Intravenous beta‐blockers have been recommended by guidelines as the mainstay first‐line therapy based on the theoretical ability to decrease aortic wall stress (Hiratzka 2010). Guidelines recommend controlling heart rate to a target of less than 60 beats per minute and a systolic blood pressure between 100 and 120 mmHg or as tolerated while maintaining adequate end‐organ perfusion (Hiratzka 2010). Calcium channel blockers (CCB), such as diltiazem and verapamil, are suggested as an alternative for chronotropic control for people with contraindications or intolerance to beta‐blockers, and can also be used to reduce blood pressure (Hiratzka 2010). If systolic blood pressure remains above target, intravenous vasodilators and angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors can also be used to reduce blood pressure (Hiratzka 2010). Once stabilized, people should be changed to oral medications and continued on medical therapy long‐term (Hiratzka 2010). Other antihypertensive medication classes include angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), diuretics, alpha‐blockers and centrally acting alpha‐agonists. Resistant hypertension occurs frequently and a median of four antihypertensive medications are used in chronic aortic dissections (Eggebrecht 2005). Guideline recommendations emphasize the use of beta‐blockers, ACE inhibitors and ARBs for antihypertensive therapy in people with thoracic aortic disease (Hiratzka 2010). However, the evidence in the approach to medical management and the selection of antihypertensive medications in chronic type B aortic dissections remains scarce. There is some evidence showing that beta‐blockers reduce aortic root dilation in children with Marfan syndrome (Shores 1994). In addition, long‐term use of beta‐blockers appears to be associated with a reduction of the need for dissection‐related surgery and the progression of aortic dilation compared with treatment with other antihypertensive medications (Genoni 2001). However, two Cochrane reviews emphasized that beta‐blockers were less effective in controlling hypertension as a first‐line therapy when compared with other antihypertensive medications (Wiysonge 2012; Wright 2009). ACE inhibitors, in particular perindopril, have also been shown to reduce aortic root diameter in people with Marfan syndrome (Ahimastos 2007). Takeshita et al. suggested that the use of ACE inhibitors could reduce the risk of long‐term aortic events in people with type B aortic dissections (Takeshita 2008). Valsartan, an ARB, demonstrated a reduction in composite cardiovascular outcomes and in aortic dissection incidences (Mochizuki 2007). In addition, one small study by Brooke et al. showed that ARBs slowed the rate of aortic root enlargement in children with Marfan syndrome (Brooke 2008). Analysis of data from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) showed CCBs to be associated with improved survival in type B aortic dissections (Suzuki 2012). Benefit with other antihypertensive medications and comparisons between different first‐line medication classes in aortic dissections remain unclear.

Why it is important to do this review

Due to the fatal nature of this cardiovascular disease, the treatments for TADs need to be well studied to maximize efficacy and improve patient prognosis. This systematic review focused on drug therapy for the treatment of type B TADs. Type B dissections tend to have a better prognosis with medical treatment compared with type A dissections. Although therapeutic guidelines have been developed, there has been limited literature on the direct comparison between the different medications used to treat TADs (Suzuki 2012).

This review will guide physicians in their clinical decision‐making on the optimal first‐line treatment for their patients. Although beta‐blockers are currently considered first‐line therapy based on guidelines, it is important to know whether this is based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compared with other drug classes. This systematic review is an attempt to answer the question whether first‐line beta‐blockers are better or worse than other first‐line drug classes for the initial drug therapy for chronic type B aortic dissection.

Objectives

To assess the effects of first‐line beta‐blockers compared with other first‐line antihypertensive drug classes for treating chronic type B TAD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs comparing different first‐line antihypertensive drug classes in the treatment of chronic type B aortic dissections. Because TAD is often a lethal complication of hypertension, studies must provide total mortality data to be included in this review.

Types of participants

People with chronic type B TADs of all etiologies (including Marfan syndrome, Ehler‐Danlos syndrome, Turner syndrome, iatrogenic or traumatic cause) that were not treated surgically as a first‐line treatment.

Types of interventions

First‐line beta‐blockers compared with other first‐line antihypertensive drug classes, such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs, CCBs, diuretics, vasodilators, renin inhibitors, alpha‐blockers and central alpha‐agonists.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Total mortality rate was the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

If medical treatment fails or if the dissection progresses, surgical intervention is usually the next therapeutic approach. The number of people not requiring surgery using these compared medical interventions was a secondary outcome. Total non‐fatal serious adverse events and aortic diameter were also secondary outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) for related reviews.

We searched the Hypertension Group Specialised Register (1946 to 26 January 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2014, Issue 1), MEDLINE (1946 to 24 January 2014), MEDLINE In‐Process, EMBASE (1974 to 24 January 2014) and ClinicalTrials.gov (to 26 January 2014). We intended to handsearch reference lists of all included studies and any relevant systematic reviews. We planned to contact the authors of appropriate studies for information about ongoing or unpublished studies.

The MEDLINE search strategy (Appendix 1) was translated into CENTRAL (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3), the Hypertension Group Specialised Register (Appendix 4) and ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 5) using the appropriate controlled vocabulary. We applied no language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

We performed an initial search of the listed databases to identify publications with potential relevance. Two review authors (KC, PL) independently screened the titles and abstracts. We excluded the studies that were clearly irrelevant.We planned to obtain the full‐text versions of the articles deemed potentially relevant and analyze them for inclusion in this review based on the specified criteria. We intended to handsearch the reference lists of any included articles to identify further studies. A third review author (JMW) would have resolved any discrepancies.

Selection of studies

We intended to use Review Manager 5 software to maintain references and abstracts after the appropriate search inclusion, based on the criteria listed above (RevMan 2012).

Data extraction and management

We had planned to have two independent review authors extract data by using a standard form, and then cross‐checked. All numeric calculations and graphic interpolations were to be confirmed by a second person.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We had planned to have two independent review authors assess the risk of bias of the selected trials according to Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using the following criteria (Higgins 2011):

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective reporting;

other sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We had planned to assess total mortality between different types of antihypertensive medications compared with first‐line beta‐blockers to treat TAD as dichotomous data to compare the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) between the different types of medications.

The total TAD‐related nonfatal serious adverse events and the number of people not requiring surgery would also be treated as dichotomous data to compare the RR with 95% CI of the respective outcomes.

If adequate data were provided, we would have assessed the effect of antihypertensive medications on the progression of aortic dimensions of the TAD as continuous data.

Dealing with missing data

In case of missing information in the included studies, we would have contacted study investigators (using email, letter, fax or a combination of these) for clarification. Longitudinal studies risk the possibility of participant drop‐out or withdrawal. Had this occurred, we would have performed assessments on a case‐by‐case basis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We would have assessed heterogeneity using the Chi2 test, with a P value < 0.05 to indicate significant heterogeneity. We would have used a fixed‐effect model when homogeneity was established and a random‐effects model if there was heterogeneity. We would have analyzed heterogeneity further using the I2 statistic to quantify the inconsistency between studies.

Data synthesis

We had planned to use the Review Manager 5 software for data synthesis and analysis (RevMan 2012). We would have presented results in tables and forest plots according to The Cochrane Collaboration guidelines. We would have presented full details of all trials in 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

People with underlying collagen diseases have a different etiology than the general population of people with TAD and we planned to consider them as a subgroup. Studies with combined populations of various etiologies may limit the availability of subgroup data and therefore, we intended to comment on these in an appendix.

Heterogeneity in the usage of different medications could be due to different medications within a medication class or the dosage used.

Results

Description of studies

We identified no RCTs comparing first‐line beta‐blockers with other first‐line antihypertensive drugs classes for the treatment of chronic type B TAD.

Results of the search

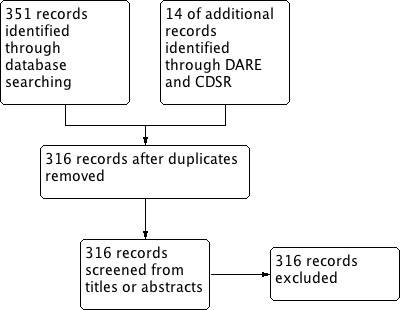

The search of seven electronic databases produced 365 records. After removing duplicates, 316 records remained. Two review authors (KC and PL) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of these records. All 316 records did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We identified no RCTs that met the inclusion criteria of this review.

Excluded studies

Two review authors (KC and PL) assessed all search results and all 316 records did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review. The majority of the search results were non‐randomized trials and were promptly excluded. Randomized studies were further assessed for their study populations and interventional procedures through evaluation of their abstracts. None of the randomized studies focused on people with an underlying aortic dissection and its medical treatment. Instead, many of the randomized studies focused on the reduction of aortic root dilation in people with Marfan syndrome or other connective tissue diseases using various therapeutic interventions. The Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group has conducted one review on endovascular versus medical therapy for uncomplicated chronic type B aortic dissections (Ulug 2012). However, the review only included one RCT, which only compared endovascular stent‐graft treatment versus 'optimal medical therapy' and did not name the drugs utilized to optimize medical therapy. After a comprehensive reading of all 316 search results, none met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

We identified no studies meeting the inclusion criteria for this review.

Effects of interventions

We identified no studies meeting the inclusion criteria for this review.

Discussion

At the time when this review was written, there was no reliable evidence to demonstrate that first‐line beta‐blockers were superior to other first‐line antihypertensive drug classes in the treatment of chronic type B TADs. Dissections involving the ascending aorta are considered life‐threatening emergencies and would demand an urgent surgical referral. Type B aortic dissections, which only involve the descending aorta, are generally managed medically unless complications such as malperfusion, progression of dissection, enlarging aneurysm or hemodynamic instability arise (Hiratzka 2010; Miller 2002). Current treatment practices have relied on retrospective or observational studies that have demonstrated variable efficacy using different treatment options (Hiratzka 2010). There is no strong source of evidence that one type of medication is superior to another.

A few non‐randomized controlled studies have attempted to look at the effects of different antihypertensive medications in people specifically with type B aortic dissections. In one study, the authors found that 18% of the people on beta‐blockers versus 55% of the people on other antihypertensive medications required dissection‐related surgery (Genoni 2001). Specific medications were not mentioned in the other antihypertensive group. Increased aortic diameter was the most important indication for surgery. The study authors concluded that although a substantial proportion of people will eventually need surgical intervention, the use of beta‐blockers reduced the progression of aortic dilation, incidence of hospital admission and late dissection‐related aortic procedures (Genoni 2001). In another study that looked at which antihypertensive medication (beta‐blockers, CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, alpha‐blockers or thiazide diuretics) prevented long‐term aortic events, the multivariate analysis showed that people taking ACE inhibitors were less likely to experience long‐term aortic events (odds ratio (OR) 0.18, P value = 0.03) and beta‐blockers did not show significant protection from long‐term aortic events (OR 0.26, P value = 0.06) (Takeshita 2008). Suzuki et al. analyzed data from IRAD to investigate the effects of medications on all‐cause mortality with a five‐year follow‐up in people with aortic dissections. Beta‐blockers were associated with improved long‐term survival in all participants and in people specifically with type A aortic dissections; however, it was the CCBs that were associated with improved survival in type B aortic dissections specifically (Suzuki 2012). The multivariate analysis found that in people with type B aortic dissections, the use of CCBs was associated with improved survival (OR 0.55, P value = 0.01), whereas, beta‐blockers were not (OR 0.72, P value = 0.38) (Suzuki 2012). Often, a combination of antihypertensive medications from different classes is needed to control blood pressure in people with chronic aortic dissections (Eggebrecht 2005). Although there are limited data on the comparison of various antihypertensive medication classes in the type B aortic dissection population, the decision of which antihypertensive medication to use will depend on patient‐specific characteristics such as intolerances, contraindications, co‐morbidities and risk of adverse effects.

There is a substantial proportion of chronic type B dissections that would require surgical treatment, typically in people with complications or who do not respond adequately to medical therapy (Hiratzka 2010). In one retrospective study using IRAD data, surgical patients tended to have a worse outcome in comparison with those receiving medical therapy (Suzuki 2003). This may be skewed since people with a type B dissection requiring surgery typically had a worse prognosis at the outset. Endovascular treatment has gained attention as a novel method in the treatment of chronic type B aortic dissections. One meta‐analysis published in 2006 demonstrated endovascular stent‐graft treatment as a feasible alternative to surgery with favorable neurologic complication and survival rates (Eggebrecht 2006). There is currently one RCT that compared endovascular treatment versus conventional optimized medical therapy, which showed no superiority of endovascular treatment over medical therapy (Nienaber 2009). This study was included in a Cochrane review by the Peripheral Vascular Diseases group (Ulug 2012).

With the current availability of clinical data on the various treatments of chronic type B aortic dissections, beta‐blockers continue to be recommended as the first‐line therapy (Hiratzka 2010). In the absence of any RCT evidence, it is presently unknown whether the benefits of this approach outweigh the harms as compared with other first‐line antihypertensive drug classes.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The key in management of chronic type B aortic dissections is to reduce mortality, morbidity and need for surgery. As of January 2014, there are no randomized controlled trials comparing first‐line beta‐blocker therapy versus other first‐line antihypertensive drug classes.

Implications for research.

Randomized controlled trials are needed to establish whether the current use of first‐line beta‐blockers is the optimal medical treatment of chronic type B aortic dissections.

Acknowledgements

The review authors would like to acknowledge the help provided by the Cochrane Hypertension Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to 24 January 2014 with daily update ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp adrenergic beta‐antagonists/ (76,037) 2 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw. (55,708) 3 (beta adj2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block$ or receptor?)).tw. (84,337) 4 or/1‐3 (136,992) 5 exp Aortic Aneurysm/ (40,464) 6 Aneurysm, Dissecting/ (12,251) 7 exp Aneurysm, Ruptured/ (13,054) 8 (aort$ adj5 (aneurys$ or dissect$ or ruptur$ or tear$ or trauma$ or split$)).tw. (37,226) 9 chronic dissect$.tw. (413) 10 or/5‐9 (55,401) 11 randomized controlled trial.pt. (359,330) 12 controlled clinical trial.pt. (86,890) 13 randomized.ab. (260,558) 14 placebo.ab. (141,189) 15 drug therapy.fs. (1,650,974) 16 randomly.ab. (186,195) 17 trial.ab. (268,087) 18 groups.ab. (1,202,660) 19 or/11‐18 (3,090,945) 20 animals/ not (humans/ and animals/) (3,775,998) 21 19 not 20 (2,628,014) 22 4 and 10 and 21 (228) 23 remove duplicates from 22 (227)

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on Wiley <Issue 1, 2014> Search date: 24 January 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ IDSearch #1 MeSH descriptor: [Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists] explode all trees #2 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol):ti,ab,kw in Trials #3 beta near/2 (adrenergic* or antagonist* or block* or receptor*):ti,ab,kw #4 (#1 or #2 or #3) #5 MeSH descriptor: [Aortic Aneurysm] explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor: [Aneurysm, Dissecting] this term only #7 MeSH descriptor: [Aneurysm, Ruptured] explode all trees #8 aort* near/5 (aneurys* or dissect* or ruptur* or tear* or trauma* or split*):ti,ab,kw #9 chronic next dissect*:ti,ab,kw #10 (#5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9) #11 (#4 and #10)

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

Database: Embase <1974 to 2014 Week 03> Search date: 24 January 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp beta adrenergic receptor blocking agent/ (241,389) 2 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw. (75,618) 3 (beta adj2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block$ or receptor?)).tw. (106,845) 4 or/1‐3 (293,693) 5 exp aorta aneurysm/ (44,056) 6 dissecting aneurysm/ (5691) 7 aneurysm rupture/ (10,430) 8 (aort$ adj5 (aneurys$ or dissect$ or ruptur$ or tear$ or trauma$ or split$)).tw. (49,614) 9 chronic dissect$.tw. (544) 10 or/5‐9 (70,381) 11 randomized controlled trial/ (367,072) 12 crossover procedure/ (39,502) 13 double‐blind procedure/ (122,206) 14 (randomi?ed or randomly).tw. (707,562) 15 (crossover$ or cross‐over$).tw. (71,851) 16 placebo.ab. (197,649) 17 (doubl$ adj blind$).tw. (149,985) 18 assign$.ab. (236,024) 19 allocat$.ab. (81,521) 20 or/11‐19 (1,101,218) 21 (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) (5,545,563) 22 20 not 21 (958,142) 23 4 and 10 and 22 (123) 24 remove duplicates from 23 (119)

Appendix 4. Hypertension Group Specialised Register search strategy

Database: Hypertension Group Specialised Register Search date: 26 January 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ #1 ((acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol)) #2 ((befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine)) #3 ((carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol)) #4 ((deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol)) #5 ((hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol)) #6 ((medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol)) #7 ((pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol)) #8 ((talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol)) #9 (beta NEAR2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block* or receptor?)) #10 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 #11 (aneurysm* NEAR2 dissect*) #12 (aneurysm* NEAR2 ruptur*) #13 (aort* NEAR (aneurys* or dissect* or ruptur* or tear* or trauma* or split*)) #14 (chronic NEAR dissect*) #15 #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 #16 #11 AND #16 #17 RCT:DE #18 #17 AND #18 (4)

Appendix 5. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

Database: ClinicalTrials.gov (via Cochrane Register of Studies) Search date: 26 January 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Search terms: "aortic dissection" OR "aortic dissections" OR "dissecting aorta" OR "dissecting aortas" Interventions: Adrenergic beta‐antagonists OR beta blocker* (3)

Differences between protocol and review

None.

Contributions of authors

Kenneth Chan and James M. Wright formulated the idea for the review and registered the review title.

Kenneth Chan and Peggy Lai developed the basis and wrote the protocol, identified and assessed the search results, and wrote the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Canada.

Lower Mainland Pharmacy Services, Canada.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

New

References

Additional references

Ahimastos 2007

- Ahimastos AA, Aggarwal A, D'Orsa KM, Formosa MF, White AJ, Savarirayan R, et al. Effect of perindopril on large artery stiffness and aortic root diameter in patients with Marfan syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 2007;298(13):1539‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brooke 2008

- Brooke BS, Habashi JP, Judge DP, Patel N, Loeys B, Dietz HC. Angiotensin II blockade and aortic‐root dilation in Marfan's syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 2008;358(26):2787‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chan 2014

- Chan KK, Rabkin SW. Increasing prevalence of hypertension among patients with thoracic aorta dissection: trends over eight decades ‐ a structured meta‐analysis. American Journal of Hypertension 2014 Feb 12;27:[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI: 10.1093/ajh/hpt293] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 1997

- Chen K, Varon J, Wenker OC, Judge DK, Fromm RE, Sternbach GL. Acute thoracic aortic dissection: the basics. Journal of Emergency Medicine 1997;15(6):859‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eggebrecht 2005

- Eggebrecht H, Schmermund A, Birgelen C, Naber CK, Bartel T, Wenzel RR, et al. Resistant hypertension in patients with chronic aortic dissection. Journal of Human Hypertension 2005;19:227‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eggebrecht 2006

- Eggebrecht H, Nienaber CA, Neuhauser M, Baumgart D, Kische S, Schmermund A, et al. Endovascular stent–graft placement in aortic dissection: a meta‐analysis. European Heart Journal 2006;27(4):489‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Genoni 2001

- Genoni M, Paul M, Jenni R, Graves K, Seifert B, Turina M. Chronic beta‐blocker therapy improves outcome and reduces treatment costs in chronic type B aortic dissection. European Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery 2001;19(5):606‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hiratzka 2010

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease: executive summary. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2010;55(14):e27‐129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Isselbacher 2007

- Isselbacher E. Epidemiology of thoracic aortic aneurysms, aortic dissection, intramural hematoma, and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers. In: Eagle K, Baliga R, Isselbacher E, Nienaber C editor(s). Aortic Dissection and Related Syndromes. Vol. 260, Springer US, 2007:3‐15. [Google Scholar]

LeMaire 2011

- LeMaire SA, Russell L. Epidemiology of thoracic aortic dissection. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2011;8(2):103‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meszaros 2000

- Meszaros I, Morocz J, Szlavi J, Schmidt J, Tornoci L, Nagy L, et al. Epidemiology and clinicopathology of aortic dissection. Chest 2000;117(5):1271‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Miller 2002

- Umana JP, Miller DC, Mitchell RS. What is the best treatment for patients with acute type B aortic dissections ‐ medical, surgical, or endovascular stent‐grafting?. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2002;74(5):S1840‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mochizuki 2007

- Mochizuki S, Dahlöf B, Shimizu M, Ikewaki K, Yoshikawa M, Taniguchi I, et al. Valsartan in a Japanese population with hypertension and other cardiovascular disease (Jikei Heart Study): a randomised, open‐label, blinded end point morbidity‐mortality study. Lancet 2007;369(9571):1431‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nicholls 1761

- Nicholls F. Observations concerning the body of His Late Majesty, October 26, 1760, by Frank Nicholls, MDFRS physician to His Late Majesty. Philosophical Transactions (1683‐1775) 1761;52:265‐75. [Google Scholar]

Nienaber 2003

- Nienaber CA, Eagle KA. Aortic dissection: new frontiers in diagnosis and management: part I: from etiology to diagnostic strategies. Circulation 2003;108(5):628‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nienaber 2009

- Nienaber CA, Rousseau H, Eggebrecht H, Kische S, Fattori R, Rehders TC, et al. Randomized comparison of strategies for type B aortic dissection: the INvestigation of STEnt Grafts in Aortic Dissection (INSTEAD) trial. Circulation 2009;120(25):2519‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2012 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

Shores 1994

- Shores J, Berger KR, Murphy EA, Pyeritz RE. Progression of aortic dilatation and the benefit of long‐term beta‐adrenergic blockade in Marfan's syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 1994;330(19):1335‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suzuki 2003

- Suzuki T, Mehta RH, Ince H, Nagai R, Sakomura Y, Weber F, et al. Clinical profiles and outcomes of acute type B aortic dissection in the current era: lessons from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation 2003;108(Suppl II):II‐312‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suzuki 2012

- Suzuki T, Isselbacher EM, Nienaber CA, Pyeritz RE, Eagle KA, Tsai TT, et al. Type‐selective benefits of medications in treatment of acute aortic dissection (from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection [IRAD]). American Journal of Cardiology 2012;109(1):122‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Takeshita 2008

- Takeshita S, Sakamoto S, Kitada S, Akutsu K, Hashimoto H. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors reduce long‐term aortic events in patients with acute type B aortic dissection. Circulation Journal 2008;72(11):1758‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Trimarchi 2010

- Trimarchi S, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, Rampoldi V, Jonker FHW, Vincentiis C, et al. Role of age in acute type A aortic dissection outcome: report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2010;140(4):784‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tsai 2006

- Tsai TT, Fattori R, Trimarchi S, Isselbacher E, Myrmel T, Evangelista A, et al. Long‐term survival in patients presenting with type B acute aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation 2006;114(21):2226‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ulug 2012

- Ulug P, McCaslin JE, Stansby G, Powell JT. Endovascular versus conventional medical treatment for uncomplicated chronic type B aortic dissection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006512.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wiysonge 2012

- Wiysonge SC, Bradley HA, Volmink J, Mayosi BM, Mbewu A, Opie LH. Beta‐blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wright 2009

- Wright JM, Musini VM. First‐line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]