Visual Abstract

Abstract

As curative therapy using allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as well as gene therapy and gene editing remains inaccessible to most patients with sickle cell disease, the availability of drug therapies that are safe, efficacious, and affordable is highly desirable. Increasing progress is being made in developing drug therapies based on our understanding of disease pathophysiology. Four drugs, hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, crizanlizumab, and voxelotor, are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, with multiple others at various stages of testing. With the limited efficacy of individual agents, combinations of agents will likely be required for optimal outcomes.

Learning Objectives

Appreciate the general approaches to the management of SCD based on disease pathophysiology

Describe the results of important drug trials in sickle cell disease, particularly those that resulted in drug approvals by regulatory agencies, while highlighting ongoing drug trials

Describe our approach to using approved drug therapies for the management of patients with sickle cell disease

CLINICAL CASE

A 28-year-old man with hemoglobin SS (HbSS) sickle cell disease (SCD) complicated by retinopathy, acute chest syndrome (ACS), nephropathy, and frequent pain episodes requiring healthcare utilization was seen in clinic for follow up. He was on hydroxyurea (∼20 mg/kg/d, his maximum tolerated dose) and losartan (25 mg/d) and was fairly adherent. Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count (WBC) of 6.2 × 109/L; an Hb level of 9.7 g/dL; a mean corpuscular volume of 110 fL; a platelet count of 292 × 109/L; an absolute neutrophil count of 3.5 × 109/L; an absolute reticulocyte count of 114.8 × 109/L; a creatinine level of 0.8 mg/dL; and a cystatin C level of 0.8 mg/L. Hb electrophoresis showed a sickle Hb (HbS) level of 81.2%; fetal Hb (HbF), 15.6%; and HbA2, 3.2%. Given his frequent pain episodes, options for optimizing his care were discussed.

Introduction

SCD affects millions of individuals worldwide.1 Although a rare disease in the United States, an estimated 230 000 children (representing the vast majority of worldwide births) were born with sickle cell anemia (referring to HbSS and HbSβ0) in sub-Saharan Africa in 2010.2 In addition to the presence of HbS, SCD is characterized by hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusive complications, and progressive end-organ dysfunction. The mortality rate for children with sickle cell anemia remains high in sub-Saharan Africa, with estimated rates of 36.4% for those younger than 5 years and 43.3% for those younger than 10 years,3 but most children in resource-rich countries live to adulthood.4 Despite increased survival to adulthood, individuals with SCD in resource-rich nations have a reduced life expectancy compared to the general population.5-8 SCD can be cured following allogeneic stem cell transplantation and possibly following gene therapy and gene editing. However, as most patients do not have access to these potentially curative treatments, the availability of safe, effective, and affordable drugs remains highly desirable.

This article reviews important historic and recent drug trials for SCD, highlighting regulatory agency–approved drug therapies and our approach to the use of these agents.

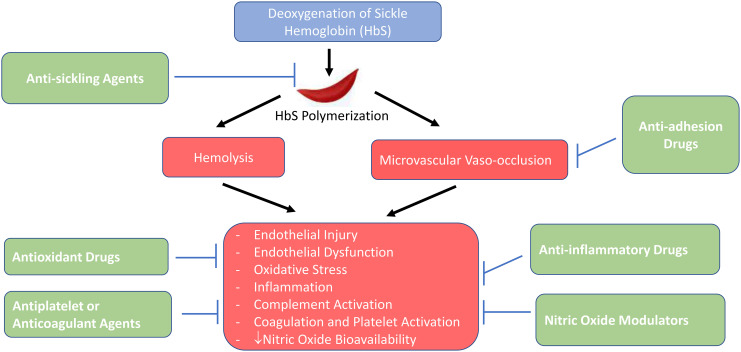

Pathophysiology

The development of effective drug therapies for SCD requires an adequate understanding of its pathophysiology. The primary event in the pathophysiology of SCD is the polymerization of HbS following deoxygenation.9 The polymerization of HbS depends on several factors, including the degree of HbS deoxygenation, the intracellular HbS concentration, and the amount of HbF.9 HbS polymerization as well as its multiple consequences, including endothelial cell injury, endothelial dysfunction, increased oxidant stress, inflammation, coagulation and platelet activation, and complement activation, is a therapeutic target in SCD. The clinical manifestations of SCD appear to be driven by 2 major pathophysiological processes: vaso-occlusion with ischemia-reperfusion injury and hemolytic anemia.1 SCD may also be divided into 2 overlapping subphenotypes: viscosity-vaso-occlusion (characterized by higher Hb levels, possibly increased blood viscosity, and clinical complications such as acute pain episodes, ACS, and avascular necrosis of bone) and hemolysis-endothelial dysfunction (characterized by lower Hb and higher levels of markers of hemolysis, including reticulocyte count, indirect bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase, and clinical complications such as leg ulcers, priapism, stroke, and pulmonary hypertension).10 This classification, while controversial, may facilitate an increased understanding of the pathobiology of SCD-related complications and the effects of therapeutic agents. The pathophysiology of SCD is beyond the scope of this article and is reviewed elsewhere.11

Drug trials for SCD

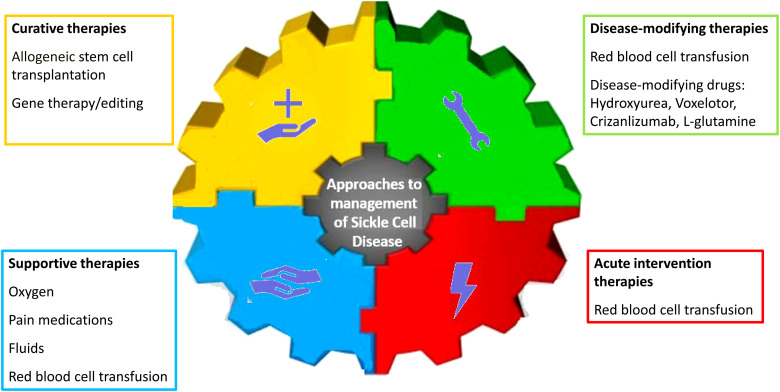

Although SCD affects multiple body organs, most trials of potentially disease-modifying drugs have focused on acute pain episodes (commonly referred to as vaso-occlusive crises, or VOCs) as their primary end point. The general approaches to the management of acute pain episodes are support, intervention, and prevention (Figure 1). No drugs have been approved for shortening the duration of acute vaso-occlusive complications (Table 1). As such, acute pain episodes are usually managed supportively. The majority of drug trials have focused on disease-modifying therapies to prevent acute pain episodes. For many years, hydroxyurea was the only drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for sickle cell anemia. More recently, however, 3 other drugs, L-glutamine, crizanlizumab, and voxelotor, have been approved for SCD. The following sections focus on phase 3 and select multicenter phase 2 studies of disease-modifying agents.

Figure 1.

Approaches to the management of SCD. Of the disease-modifying therapies, 4 drugs, hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, crizanlizumab, and voxelotor, are currently approved by the FDA. In the absence of long-term data, gene therapy and gene editing are referred to as “potentially curative therapies.”

Table 1.

Major historical acute intervention and prevention trials for VOCs in SCD

| Acute intervention trials for VOCs | Prevention trials for VOCs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Primary efficacy end point | Results | Reference | Drug | Primary efficacy end point | Results | Reference |

| Cetiedil | Effect on course of pain crisis | Cetiedil (0.4 mg/kg) significantly reduced the number of painful sites on all treatment days and shortened the total time in crisis. | Benjamin et al57 | Sodium cyanate | Effect on hemolytic rate and frequency of crisis | Decrease in the hemolytic rate (evidenced by increased Hb) and mean frequency crisis was seen in patients receiving cyanate. Increase in Hb was directly proportional to the amount of carbamylation achieved. Frequency of crisis was decreased in patients with higher carbamylation. |

Gillette et al58 |

| Methylprednisolone | Effect on duration and severity of pain crisis | Reduced duration of inpatient analgesic therapy, but majority of patients were readmitted for recurrent pain. | Griffin et al59 | Ticlopidine | Effect on pain crisis | Treatment with ticlopidine decreased the number of VOCs, mean duration of VOCs, and severity of VOCs. | Cabannes et al50 |

| Purified poloxamer-188 | Effect on duration of pain crisis | In an earlier study, poloxamer-188 significantly reduced the duration of VOC, especially in children (≤15 years) and patients receiving concurrent hydroxyurea. Subsequent study showed no significant difference in the mean time to the last dose of parenteral opioids between poloxamer-188 and placebo. |

Orringer et al34; Casella et al35 | Hydroxyureaa | Effect on frequency of painful crises in adults and children | Treatment with hydroxyurea significantly reduced VOCs, hospitalizations due to VOCs, ACS, and blood transfusion compared to placebo. | Charache eta al13; Wang et al14 |

| Inhaled NO | Effect on time to resolution of VOC | An earlier study showed significantly less morphine use over 6 hours but no difference between inhaled NO and placebo on duration of hospitalization. A subsequent larger study showed no significant difference in median time to resolution of VOC, length of hospitalization, or median opioid usage between inhaled NO and placebo. |

Gladwin et al41; Weiner et al60 | Senicapoc | Effect on frequency of painful acute sickle cell–related crises | Phase 2 study showed a dose-dependent increase in Hb with senicapoc vs placebo. Phase 3 study showed increase in Hb but no significant reduction in VOC compared to placebo. |

Ataga et al25 |

| Tinzaparin | Effect on painful crisis | Tinzaparin significantly reduced the severity and duration of VOC and duration of hospitalization. | Qari et al53 | Prasugrel | Rate of VOC (composite of painful crisis or ACS) | No significant difference in the rate of VOC between prasugrel and placebo. | Heeney et al51 |

| Arginine | Efficacy in children requiring hospitalization for severe pain necessitating parenteral narcotics | Arginine significantly reduced total analgesic usage, pain scores, time to crisis resolution, and total length of hospital stay. | Morris61 | L-glutaminea | Number of pain crises | Treatment with L-glutamine resulted in reduced VOC, hospitalizations, and ACS compared to placebo. | Niihara et al27 |

| Sevuparin | Effect on duration of VOC in hospitalized patients | No difference in time to VOC resolution or discontinuation of IV opioids between sevuparin and placebo. | Biemond33 | Crizanlizumaba | Annual rate of sickle cell–related pain crises | In the phase 2 SUSTAIN trial, crizanlizumab significantly decreased median rate of VOC and increased median times to first and second VOC. In the phase 3 STAND trial, no significant difference in the annualized rates of VOC was seen with crizanlizumab compared to placebo. |

Ataga et al29; Novartis AG30 |

| Rivipansel | Effect on time to resolution of VOC | In phase 2 trial, treatment with rivipansel significantly reduced cumulative IV opioid dose and resulted in clinically meaningful reduction in time to crisis resolution. In the phase 3 trial, no significant benefit was seen in shortening the time to readiness for discharge, time to discharge, or discontinuation of IV opioids. |

Telen et al31; Dampier et al32 | NAC | Effect on frequency of SCD pain days | No reduction in the rate of SCD-related pain days per patient-year, hospital admission days, number of admissions, or days with home analgesic use with NAC+ compared to placebo. | Sins et al28 |

| Regadenoson | Effect on reduction in invariant natural killer T-cell activation in patients admitted for acute pain crisis | Regadenoson infusion did not decrease the hospitalization duration, total opioid use, or pain scores compared with placebo. | Field et al37 | Canakinumab | Effect on change in average daily pain scores | No decrease in daily SCA-related pain, but canakinumab significantly reduced markers of inflammation compared with placebo. | Rees et al39 |

| Magnesium | Effect on length of stay in patients hospitalized for VOC | IV magnesium use did not shorten the length of hospitalization, reduce opioid use, or improve quality of life compared to placebo. | Brousseau et al26 | Ticagrelor | Effect on the rate of VOCs (composite of painful crises and/or ACS) | No reduction in VOC with ticagrelor compared to placebo. | Heeney et al52 |

ACS, acute chest syndrome; Hb, hemoglobin; IV, intravenous; NAC, N-acetyl cysteine; SCA, sickle cell anemia; VOC, vaso-occlusive crisis.

Clinical trials resulted in approval of these drugs by the FDA.

Drugs that inhibit HbS polymerization

Multiple mechanisms can prevent HbS polymerization: 1) inhibition of sickle fiber intermolecular contacts; 2) increase in HbF; 3) decrease of intracellular HbS concentration; 4) increase of oxygen affinity; and 5) decrease in 2,3-diphosphoglycerate concentration.12

Hydroxyurea, an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, is thought to exert its therapeutic effects largely by inducing HbF, although the mechanisms of HbF induction remain unclear. Hydroxyurea was approved for adults based on the results of the double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial of hydroxyurea in 299 patients with sickle cell anemia, which showed significant reductions of VOCs (median, 2.5 vs 4.5 crises per year; P < .0001), hospitalizations due to crises (median annual rates, 1.0 vs 2.4; P < .001), ACS (25 vs 51 patients; P < .0001), and blood transfusions (48 vs 73 patients; P = .001; and 336 vs 586 units of blood; P = .004) following treatment with hydroxyurea vs placebo.13 Similar findings were observed in the multicenter BABY HUG trial in which treatment with hydroxyurea significantly reduced disease-related acute complications in young children with sickle cell anemia.14 Based on this, a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) expert panel strongly recommended offering hydroxyurea to children as young as 9 months with sickle cell anemia.15 Hydroxyurea was approved in the United States for children aged 2 years or older in 2017 based on findings from an open- label, single-arm trial that showed significant decreases in acute vaso-occlusive events and transfusion requirements.16 Although no significant differences were observed in the intention-to-treat analysis, hydroxyurea reduced the risk of conversion from conditional to abnormal transcranial Doppler (TCD) velocity compared with observation (0 vs 50%; P = .02) in post–host analysis of a multicenter trial.17 In individuals with abnormal TCD on chronic blood transfusion and no severe vasculopathy, hydroxyurea was also noninferior to chronic red blood cell (RBC) transfusion in preventing stroke.18 In this trial the final model-based TCD velocities for standard transfusions vs hydroxyurea were 143 cm/s (95% CI, 140-146) vs 138 cm/s (95% CI, 135-142), with a difference of 4.54 (95% CI, 0.10-8.98; P = 8.82 × 10−16 for noninferiority, and P = .023 for superiority post hoc). In the REACH study, the treatment of 606 children from 4 sub-Saharan countries with hydroxyurea significantly increased total Hb (an increase of 1.0 g/dL; 95% CI, 0.8-1.0) and HbF levels (an increase of 12.5%; 95% CI, 11.8-13.1) and decreased the rates of vaso-occlusive pain (98.3 vs 44.6 events per 100 patient-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.45; 95% CI, 0.37-0.56), RBC transfusions (43.3 vs 14.2 events per 100 patient-years; IRR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.23-0.47), and mortality (3.6 vs 1.1 deaths per 100 patient-years; IRR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.10-0.88) when compared with the pretreatment period.19 In a double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 trial of 220 children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal TCD velocities conducted in Nigeria, no significant difference was seen in the stroke incidence rate with low-dose hydroxyurea (10 mg/kg) compared with moderate-dose hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg), although the incidence rate for all-cause hospitalization was lower with moderate-dose hydroxyurea.20 Furthermore, no significant difference in the incidence rates of the primary outcome measures (stroke, transient ischemic attack, and death) was seen with low-dose vs moderate-dose hydroxyurea for secondary prevention of stroke.21

Voxelotor is an HbS polymerization inhibitor that reversibly binds to Hb and stabilizes it in the oxygenated (relaxed) state.22 In the multicenter phase 3 HOPE study, 274 patients (12 years and older) with SCD were randomized to receive a daily dose of 1500 mg of voxelotor, 900 mg of voxelotor, or placebo for 72 weeks. In the intention-to-treat analysis, 51% (95% CI, 41-61) of participants who received 1500 mg/d achieved a Hb increase of greater than 1 g/dL from baseline after 24 weeks of therapy compared to 7% (95% CI, 1-12) in the placebo group. Treatment with voxelotor at 1500 mg/d also resulted in a significant increase in Hb (mean change, 1.14 g/dL vs −0.1 g/dL; P < .001) and significant decreases in indirect bilirubin (mean change, −29.1% vs −3.2%; P < .001) and percent reticulocyte count (mean change, −19.9% vs 4.5%; P < .001) compared to placebo.23 Similarly, a Hb increase of more than 1 g/dL from baseline after 24 weeks of voxelotor was observed in 47% of children with HbSS or HbSβ0 in the HOPE KIDS-1 trial.24

Senicapoc, a potent blocker of the Gardos channel, a calcium- activated potassium channel of intermediate conductance in RBCs, improves RBC hydration by reducing the loss of solute and water. However, an increase in Hb (mean change, 0.59 g/dL vs −0.1 g/dL; P < .001) and decreases in percent reticulocyte count (mean change, −2.46% vs −0.79%; P < .001) and indirect bilirubin (mean change −16.6 µmol/L vs −0.3 µmol/L; P < .001), both markers of hemolysis, following senicapoc administration were not accompanied by a significant reduction in acute pain episodes.25 Magnesium inhibits K+ efflux through the potassium chloride cotransport channel in RBCs and consequently prevents RBC dehydration. Treatment with intravenous (IV) magnesium when compared with placebo did not shorten the length of hospitalization (median, 56 hours; interquartile range [IQR], 27.0-109.0 vs 47 hours [IQR, 24.0-99.0]; P = .24), reduce opioid use (median, 1.46 mg/kg vs 1.28 mg/kg morphine equivalents; P = .12), or improve quality of life in children and young adults who were hospitalized for acute pain episodes.26 Table 2 lists actively recruiting studies of antisickling agents.

Table 2.

Actively recruiting clinical trials of antisickling agents in SCD

| Mechanism | Drug | Sponsor | NCT number (study acronym) | Clinical phase | Study design/Intervention | Number/age | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbF induction | Hydroxyurea | ADDMEDICA SASA |

NCT03806452 (SIKAMIC) |

Phase 2 | Oral 15 mg/kg/d for 6 mo vs placebo | 120/ ≥ 18 y | Proportion of patients with at least a 30% decrease in ACR, mean change in GFR, change in ACR, systolic blood pressure, adverse events. |

| Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati |

NCT03789591 (HOPS) |

Phase 3 | Starting hydroxyurea dose 20 mg/kg/d vs PK-guided initial hydroxyurea dose | 116/6 mo-21 y | Evaluate HbF, F cells, gene-expression patterns | ||

|

NCT02286154 (TREAT) |

N/A | Open-label, single-arm study Old cohort: includes participants already on hydroxyurea upon study entry New cohort: includes participants starting hydroxyurea with starting dose predicted using PK/PD data |

150/6 mo-21 y | Evaluate time to reach maximum tolerated dose, hydroxyurea adherence, neurological function (TCD), splenic (pit count), kidney (BUN/creatinine, urinalysis, cystatin-c) and cardiac function (echo/ECG) | |||

| Nicotinamide vs THU and decitabine | EpiDestiny Inc; National Institutes of Health; NHLBI | NCT04055818 | Phase 1 | Oral nicotinamide vs THU plus decitabine for 12 wk followed by combination for a further 12 wk | 20/ ≥ 18 y | Compare effect of oral nicotinamide vs THU-decitabine and in combination on Hb level at week 12 | |

| Allosteric modifier (to the R-state) | Voxelotor (formerly GBT440) | Global Blood Therapeutics |

NCT02850406 (HOPE Kids) |

Phase 2a | Oral, open-label, single- and multiple-doses study Part A: single dose Part B: 24 wk Part C: 48 wk |

125/4-17 y | Pharmacokinetics, change in Hb, effect on hemolysis, TCD velocity, safety |

| NCT04188509 | Phase 3 | Oral, open-label | 50/4-18 y | Evaluate safety and tolerability, SCD-related complications | |||

| NCT04335721 | Phase 1/2 | Open label, voxelotor vs standard of care (observation) | 12/ ≥ 18 y | Evaluate change in albuminuria and other kidney function measures (24-h urine protein, eGFR, serum creatinine, serum cystatin C) | |||

|

NCT05561140 (RESOLVE) |

Phase 3 | Oral daily voxelotor vs placebo for 12 wk | 80/ ≥ 12 y | Evaluate effect on healing of leg ulcers, time to resolution of target ulcer, change in total surface area of target ulcer, and incidence of new ulcers | |||

| NCT05228834 | Phase 3 | Oral daily voxelotor vs placebo for 12 wk | 80/8-17 y | Evaluate change in executive abilities composite score, processing speed, nonexecutive cognitive abilities, change in hematological parameters, HRQOL score | |||

| Robert Clark Brown | NCT05018728 | Phase 2 | Oral daily voxelotor × 12 wk | 50/4-17 y | Change in cerebral blood flow, oxygen extraction fraction, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen, Hb, voxelotor-modified Hb | ||

| Emory University |

NCT05018728 (VoxSCAN) |

Phase 2 | Open label, once daily for 12 wk | 12/4-17 y | Evaluate effect on cerebral hemodynamics including cerebral blood flow, oxygen extraction fraction. | ||

| GBT021601-012 | Global Blood Therapeutics |

NCT05431088 (GBT021601-021) |

Phase 2/3 | Initial 1:1 randomization to 100 mg and 150 mg, after review of safety data of 150 mg, then randomization 1:1:1 to 100 mg, 150 mg, and 200 mg | 480/6 mo-65 y | Safety, pharmacokinetics, proportion of participants with increase in Hb >1 gm/dL at week 48 | |

| Allosteric activator of RBC pyruvate kinase-R | Mitapivat sulfate (AG-348) | Agios Pharmaceuticals |

NCT05031780 (RISE UP) |

Phase 2/3 | Phase 2: oral, twice daily 50-mg dose vs 100-mg dose vs placebo × 12 wk followed by open-label extension period for 216 wk Phase 3: based on phase 2 results either 50 mg or 100 mg twice daily vs placebo for 52 wk followed by open label extension period for 216 wk |

267/ ≥ 16 y | Safety, adverse events, change in Hb, effect on hemolysis, effect on annualized rate of pain crisis, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, QOL measures |

| AG- 946 | Agios Pharmaceuticals | NCT04536792 | Phase 1 | Single and multiple ascending dose study Part 1: single dose Part 2: once daily for 14 d Part 3: once daily for 28 d |

64/18-70 y | Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics | |

| Etavopivat (FT 4202) | Forma Therapeutics | NCT04987489 | Phase 2 | Open label, 400 mg once daily in transfusion-dependent sickle cell participants and in transfusion and non–transfusion dependent thalassemia participants | 60/12-65 y | Safety, evaluate proportion of participants with reduction in blood transfusion requirement, change in Hb, ferritin, and liver iron concentration | |

|

NCT04624659 (HIBISCUS) |

Phase 2/3 | Phase 2: once daily, 200-mg dose vs 400-mg dose vs placebo for 24 wk Phase 3: based on phase 2 results either 200 mg or 400 mg once daily vs placebo for 28 wk, followed by 52-wk open-label extension period |

344/12-65 y | Safety, change in Hb, markers of hemolysis, effect on annualized pain crisis rate, patient reported outcome measures (PROMIS) |

ACR, albumin creatinine ratio; BUN, serum urea nitrogen; ECG, electrocardiogram; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate;

HRQOL, health-related quality of life; N/A, not available; PK/PD, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics; R-state, relaxed state; QOL, quality of life; THU, tetrahydrouridine.

Antioxidant, antiadhesive, and anti-inflammatory agents

Oxidative stress is a major contributor to the pathophysiology of SCD. L-glutamine, a conditionally essential amino acid, is a precursor for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), increases the NAD redox ratio within sickle RBCs, and may improve RBC health by reducing oxidative stress. In a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of 230 patients with HbSS or HbSβ0, L-glutamine, administrated twice daily, significantly reduced acute pain episodes (3.0 vs 4.0; P = .005) and hospitalizations (2.0 vs 3.0; P = .005) compared to placebo.27 Treatment with L-glutamine also resulted in a significantly lower cumulative number of hospital days and fewer occurrences of ACS compared with placebo. Treatment with another antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), at a dose of 600 mg twice a day for 6 months did not significantly decrease the rate of SCD-related pain days per patient-year, days of hospital admission, number of admissions, or days with home analgesic use compared with placebo.28

Antiadhesion agents may improve flow in the microvasculature by reducing abnormal cell-cell (RBC, leukocyte, platelet, endothelial cell) interactions. Crizanlizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–P-selectin antibody, blocks the interaction between P-selectin (expressed on activated endothelial cells and platelets) and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1. In the SUSTAIN trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial, crizanlizumab administered at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg via IV every 4 weeks (following an initial loading dose) in a 52-week period was compared with placebo in individuals with SCD.29 Treatment with high-dose crizanlizumab (5 mg/kg) resulted in a significantly lower median rate of painful crisis (1.63 vs 2.98; P = .01), a lower median rate of uncomplicated crisis (1.08 vs 2.91; P = .02), and longer median times to occurrence of the first (4.07 months vs 1.38 months; P = .001) and second pain crises (10.32 vs 5.09 months; P = .02). The benefit in reducing pain crisis was observed regardless of the ongoing use of hydroxyurea, pain crisis frequency in the previous 12 months, or SCD genotype. However, recently reported results from the phase 3 STAND trial showed no significant difference between either crizanlizumab at 5 mg/kg or 7.5 mg/kg and placebo on the annualized rates of VOC leading to a healthcare visit over the first year postrandomization, although there were no new safety concerns.30 Based on these results, the European Medicines Agency's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use concluded that the benefits of crizanlizumab do not outweigh its risks and recommended the revocation of its marketing authorization in the European Union.

Rivipansel (previously called GMI-1070) is a small-molecule pan- selectin inhibitor with highest affinity to E-selectin. In a multicenter phase 2 trial, rivipansel reduced the cumulative IV opioid dose during acute pain episodes by 83% compared to placebo.31 However, in a multicenter, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (RESET), no benefit was seen with rivipansel in shortening the times to readiness for discharge, hospital discharge, or discontinuation of IV opioids.32 In a post hoc analysis, the early initiation of rivipansel within 26.4 hours of crisis onset resulted in clinically meaningful reductions in median time to readiness for discharge by 56.3 hours (from 122.0 to 65.7 hours; hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; P = .033), median time to discharge by 41.5 hours (from 112.8 to 71.3 hours; HR, 0.54; P = .010), and time to discontinuation of IV opioids by 50.5 hours (from 104.0 to 53.5 hours; HR, 0.58; P = .026), compared with placebo.32 Sevuparin, a low-molecular- weight heparin-derived polysaccharide with antiadhesive properties but minimal anticoagulant activity, did not shorten the times to VOC resolution or discontinuation of IV opioids vs placebo when administered during acute pain episodes.33

Poloxamer-188, a nonionic block copolymer surfactant that improves microvascular blood flow and reduces hydrophobic cell-cell interactions, has been evaluated in patients hospitalized for acute pain episodes. In an earlier study, poloxamer-188 significantly shortened the duration of acute pain episodes when compared with placebo (mean, 133 hours [standard deviation, 41] vs 141 hours [standard deviation, 42]; P = .04).34 However, with an absence of documentation of the study's crisis resolution criteria in approximately 24% of participants (30% in the placebo arm vs 18% in the poloxamer-188 arm), another trial was conducted. This subsequent study showed no significant difference in the time to discontinuation of IV opioids when poloxamer-188 was compared to placebo (81.8 hours vs 77.8 hours; P = .09).35

Multiple agents have been evaluated to mitigate the effects of inflammation in SCD.36 Regadenoson, a partially selective adenosine A2A receptor agonist that decreases the activation of invariant natural killer T cells, did not decrease the duration of hospitalization (3.96 days vs 3.99 days; P = .80), total opioid use (median morphine equivalent dose, 0.03 mg/kg/h vs 0.04 mg/ kg/h; P = .34), or pain scores (−2.68 vs −2.80; P = .91) when compared with placebo.37 Treatment with SC411, a docosahexaenoic acid ethyl ester formulation, for 8 weeks significantly reduced levels of D-dimer (P = .025) and soluble E-selectin (P = .0219) and increased Hb (mean change, 0.97 g/dL vs 0.33 g/dL; P = .04) when compared with placebo.38 Canakinumab (ACZ885), a monoclonal anti–interleukin 1 beta antibody, was well tolerated in a 6-month study. Although the trial did not achieve its prespecified primary end point for diary-reported daily pain scores, treatment with canakinumab resulted in reductions in markers of inflammation (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, absolute counts of leukocytes, monocytes) and number/duration of hospitalizations as well as trends for improvement in pain intensity, fatigue, and absences from school or work when compared with patients in the placebo arm.39 Montelukast, a leukotriene inhibitor, did not significantly decrease levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and reported pain when compared to placebo following 8 weeks of treatment.40 Actively recruiting studies of antioxidants, antiadhesive and anti-inflammatory agents are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Actively recruiting clinical trials of antioxidants, antiadhesive, and anti-inflammatory agents in SCD

| Mechanism | Drug | Sponsor | NCT number (study acronym) | Clinical phase/status | Study design/intervention | Number/age | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-selectin antagonist | Crizanlizumab | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | NCT03938454 (SPARTAN) | Phase 2 | IV infusion every 2 wk for first month and then every 4 wk × 51 wk | 56/ ≥ 16 y |

Evaluate efficacy in priapism, uncomplicated VOC events |

| NCT04657822 | Phase 4 | Open-label extension study, IV infusion every 2 wk for first month and then every 4 wk | 130/all ages | Evaluate the frequency of treatment-related adverse events | |||

| NCT03474965 | Phase 2 | Open label extension study, IV infusion every 2 wk for first month and then every 4 wk | 119/6 mo-17 y | Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety, pain crisis rate | |||

| Inclacumab | Global Blood Therapeutics | NCT04927247 | Phase 3 | Single IV dose (30 mg/kg) of inclacumab vs placebo after VOC event (that required hospitalization and IV pain medication) | 280/ ≥ 12 y | Evaluate proportion of participants with readmission for VOC within 90 d, time to readmission, pharmacodynamics | |

| NCT04935879 | Phase 3 | Inclacumab (30 mg/kg) vs placebo administered IV every 12 wk for 48 wk | 240/ ≥ 12 y | Safety and effect on VOC including frequency of VOC during treatment period, time to first and second VOC, hospitalization duration | |||

| NCT05348915 | Phase 3 | Open-label extension study, inclacumab (30 mg/kg) IV every 12 wk | 520/ ≥ 12 y | Safety, evaluate annualized rate of VOC, hospitalizations, complicated VOCs, transfusions, pharmacokinetics | |||

| Blockade of fcγriii receptors | IVIG | Albert Einstein College of Medicine | NCT01757418 | Phase 1/2 | Single dose of IVIG vs placebo given within 24 h of hospitalization | 94/12-65 y | Length of VOC, total opioid use, time to end of VOC, in vitro adhesion studies |

| Antioxidant | Glutamine | Ain Shams University | NCT05371184 | Phase 4 | 0.3 gm/kg/dose twice daily orally (up to a maximum of 15 g/dose) for 24 wk | 30/2-18 y | Incidence of pain crisis, change in transcranial Doppler |

| Anti-inflammatory | Rifaximin (antibiotic, decrease aged neutrophils) | Bausch Health Americas Inc | NCT05098028 | Phase 2a | Oral, extended release (high and low dose) vs delayed extended release (high and low dose) vs placebo | 60/18-70 y | Evaluate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics |

| Crovalimab (anticomplement C5 monoclonal antibody) | Hoffmann-La Roche |

NCT04912869 (CROSSWALK-a) |

Phase 1 | Single IV infusion of crovalimab vs placebo for management of uncomplicated VOC | 30/12-55 y | Safety, adverse events, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, time to resolution of VOC, cumulative opioid dose, time to discontinuation of parenteral opioids, percentage of participants with VOC complication (ACS, ICU, blood transfusion) | |

|

NCT05075824 (CROSSWALK-c) |

Phase 2 | IV loading dose of crovalimab on day 1, followed by SQ dose day 2 and then weekly for 3 wk. Monthly maintenance SQ dosing starting week 5 for 48 wk vs placebo. | 90/12-55 y | Evaluated effect on frequency of VOC events, ACS events, duration of hospitalization, change in urine albumin-creatinine ratio, tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity, and PROMIS score | |||

| Tocilizumab (anti- interleukin 6) |

University of Chicago | NCT05640271 | Phase 2 | Single 80-mg IV dose at time of ACS diagnosis followed by placebo (50 mL normal saline) 48 h later. Control arm receives placebo first followed by tocilizumab 48 h later. | 200/ ≥ 18 y | Changes in peripheral oxygen saturation, changes in the route, rate, and FiO2 of supplemental oxygen delivery from day 0 to day 4. The time-weighted SaO2/FiO2 ratio will be calculated based on this. | |

| ALXN1820 (bispecific- antiproperdin antibody) |

Alexion |

NCT05565092 (PHOENIX) |

Phase 2a | Open-label study to evaluate multiple dosing regimens (i) 300 mg SQ weekly, (ii) 600 mg SQ every 4 wk, (iii) 300 mg SQ every 2 wk |

30/18-65 y | Safety, pharmacokinetics, changes from baseline in Hb, hemolysis markers, hemopexin, complement activity, and concentration of properdin and complement biomarkers |

FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU, intensive care unit; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; PROMIS, patient-reported outcome measures; SaO2, oxygen saturation; SQ, subcutaneous.

Nitric oxide and related agents, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants

Abnormalities of the nitric oxide (NO)-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent signaling pathway may play a role in the inflammation and vascular dysfunction seen in SCD. As a result of ongoing hemolysis, scavenging of NO, and subsequent endothelial dysfunction, NO and related agents may provide benefit to patients with SCD. In a phase 2 multicenter study of SCD patients experiencing acute vaso-occlusive episodes, inhaled NO did not significantly shorten the median time to resolution of vaso-occlusive episodes (73 hours [95% CI, 46.0-91.0] vs 65.5 hours [95% CI, 48.1-84.0]; P = .87) or the median length of hospitalization (4.1 days [IQR, 2-6] vs 3.1 days [IQR, 1.7-6.4]; P = .30) or reduce the median opioid usage (2.8 mg/kg [1.4-6.1] vs 2.9 mg/kg [1.1-9.9]; P = .73) or the rate of ACS when compared to placebo.41 In a separate study, inhaled NO did not reduce the rate of treatment failure in adult patients with mild to moderate ACS.42 L-arginine is an obligate substrate for NO production. In a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of children in Nigeria, oral L-arginine therapy administered within 6 hours of presentation for a pain crisis significantly reduced total analgesic usage, quantified using the mean analgesic medication quantification scale (73.4 [95% CI, 62.4-84.3] vs 120.0 [96.7-143.3]; P < .001), pain scores (1.50 [1.23-1.77] vs 1.09 [0.94-1.24]; P = .009), time to crisis resolution (75.8 ± 36 hours [95% CI, 63.4-88.2] vs 93.3 ± 32.7 hours [95% CI, 81.7-104.9]; P = .02), and the total length of hospital stay (105 hours [IQR, 72-144] vs 141 hours [IQR, 117-205]; P = .002).43 However, patients treated with sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor that increases NO-mediated effects by inhibiting cGMP degradation, experienced more serious adverse events, predominantly hospitalization for pain, but no clinical benefits when compared to placebo.44

Platelet activation occurs in SCD at steady state, with further activation during acute pain episodes.45-49 Although ticlopidine was previously shown to decrease the number, the mean duration, and the severity of acute pain episodes,50 more recent phase 3 trials of the newer-generation P2Y12 receptor blockers, prasugrel and ticagrelor, did not show a benefit in reducing the frequency of vaso-occlusive episodes compared to placebo.51,52 Tinzaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, significantly reduced the durations of acute pain episodes (mean difference in duration of painful crises, −1.78 days; 95% CI, −1.94 to −1.62; P < .0001) and hospitalization (mean difference in duration of hospitalization, −4.98 days; 95% CI, 5.48 to −4.48; P < .0001) when compared to placebo.53 However, it is uncertain whether the beneficial effects were a result of its anticoagulant or antiadhesive effects. Table 4 shows actively recruiting trials of NO and related agents, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants.

Table 4.

Actively recruiting clinical trials of NO and related agents, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants in SCD

| Mechanism | Drug | Sponsor | NCT number (study acronym) | Clinical phase/status | Study design/intervention | Number/age | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased NO production | Arginine | Emory University | NCT02447874 | Phase 1/2 | IV infusion 3 times a day for maximum of 7 d | 21/7-21 y | Pharmacokinetics, NO metabolites |

|

NCT04839354 (STArT trial) |

Phase 3 | One-time L-arginine loading dose (200 mg/kg IV) + standard dose (100 mg/kg IV 3 times a day) | 360/3-21 y | Evaluate change in time to crisis resolution, pain scores, total parenteral opioid use, PROMIS pain interference, pain-behavior and fatigue score | |||

| L-citrulline | Asklepion Pharmaceuticals | NCT04852172 | Phase 1/2 | IV infusion (bolus + continuous infusion for 7 h) during VOC Part 1: identify optimum dose regime Part 2: doses selected from part 1 vs placebo |

120/6-21 y | Pharmacokinetics, adverse events, effect on VOC including amount of overall opioid use, time to resolution of VOC |

Our approach to the use of approved drugs

As most patients have limited access to curative therapies, pharmacotherapy may offer the best hope for improved patient outcomes at this time. In the absence of clinical trials comparing available drugs, the choice of initial therapy may be guided by a patient's clinical presentation as well as the availability and cost of drugs (Table 5). Patients with frequent vaso-occlusive complications (such as acute pain episodes or ACS) may obtain benefit from the use of hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, and crizanlizumab, while hemolytic anemia may be improved with the use of hydroxyurea and voxelotor. Despite the negative results of the STAND trial, we continue to use crizanlizumab on a case-by-case basis as several studies other than the SUSTAIN trial suggest a benefit to decreasing the frequency of painful episodes leading to health center visits.54-56 As approved drug therapies have limited clinical efficacy, most complications related to SCD are unlikely to be ameliorated by a single drug. Consequently, patients are most likely to obtain maximum benefit using a combination of drugs with different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping side effects. While more data are necessary to evaluate the effects of drug combinations, previous studies of L-glutamine, crizanlizumab, and voxelotor showed that these agents in combination with hydroxyurea were beneficial, without increased toxicity.

Table 5.

Summary characteristics of FDA-approved drugs for SCD

| Hydroxyurea | L-glutamine | Crizanlizumab | Voxelotor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≥2 | ≥5 | ≥16 | ≥4 |

| Genotypes | HbSS, HbSβ0 thalassemia | All genotypes (only studied in HbSS, HbSβ0 thalassemia) | All genotypes | All genotypes (majority with HbSS, HbSβ0 thalassemia) |

| Mechanism of action | Multiple, but primarily by increasing HbF production | Uncertain, but thought to increase NAD redox potential; may decrease cell adhesion | Anti–P-selectin inhibitor (decreases adhesion of WBC, RBC to endothelium and possibly of platelets to WBC) | Decreases HbS polymerization by increasing Hb-oxygen affinity |

| Route of administration | Oral (capsules/tablets) | Oral (powder) | IV | Oral (tablets) |

| Clinical effects of therapy | Decreased frequency of VOC, decreased frequency of ACS, decreased hospitalization, decreased RBC transfusion requirement, decreased stroke risk | Decreased frequency of VOC, decreased frequency of ACS, decreased hospitalization | Decreased frequency of VOC in phase 2 SUSTAIN trial. Results of recent phase 3 STAND trial showed no benefit. | Increased Hb |

| Effect size for primary end point (NNT) | 44% decrease in VOC per year (median from 4.5 to 2.5); IRR, 0.56 | 25% decrease in VOC in 48 wk (median from 4 to 3); IRR, 0.75 | 45% decrease in crisis rate per year (median from 3 to 1.6); IRR, 0.55 | 7-fold increase in the Hb responders (7 to 51) at 24 wk, incidence proportion ratio = 7.3a |

| Common toxicities | Myelosuppression, skin hyperpigmentation, nail discoloration, teratogenicity, decreased sperm counts, nausea and vomiting | Constipation, nausea, headaches, abdominal pain | Nausea, arthralgia | Headache, diarrhea, nausea |

| Pharmacokinetics | Excreted via kidneys. Adjust dose for eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Use with caution with hepatic and renal impairment, but no recommended dose adjustment | No dosage adjustments in manufacturer labeling for renal and hepatic impairment (not tested in ESRD) | No dosage adjustment for renal impairment, but not yet studied in ESRD requiring dialysis. Dose reduction for severe liver disease (Child Pugh class C) |

| Cost | $ | $$$ | $$$$$ | $$$$$ |

ACS, acute chest syndrome; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HbF, fetal hemoglobin; HbS, sickle hemoglobin; IV, intravenous; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NNT, number needed to treat; VOC, vaso-occlusive crisis.

Patients treated with 1500 mg of voxelotor had 7.3 times the increased proportion of Hb responders (>1 g/dL increase from baseline at 24 weeks).

Data adapted from Rai and Ataga.62

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

In the absence of identifiable precipitating factors and following confirmation of adherence with hydroxyurea, other treatment options for acute pain episodes were extensively discussed. While continuing hydroxyurea, the patient began on L-glutamine because he wished to avoid monthly infusion clinic visits. He was, however, switched to crizanlizumab due to poor tolerance of L-glutamine. He experienced a substantial reduction in the frequency of acute pain episodes over the next year.

Conclusion

Although SCD is an orphan disease in the United States, it is common worldwide. With advances in the understanding of disease pathophysiology, multiple drugs have been approved by regulatory agencies, with more in various stages of clinical testing. The development of new drugs for SCD offers opportunities to test drug combinations in the hope of improved clinical outcomes. Although the majority of drug trials in SCD have evaluated acute pain episodes as the primary clinical end point, other SCD- related complications and surrogate end points are increasingly being assessed. Demonstrating the benefit of drug therapies on end-organ dysfunction in SCD will provide further evidence for their role in improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgment

Kenneth I. Ataga is supported by awards from the FDA (R01FD006030) and NHLBI (HL159376).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Parul Rai: consultancy: Global Blood Therapeutics.

Kenneth I. Ataga: research funding: Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Takeda Pharmaceuticals; advisory board member: Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Fulcrum Therapeutics, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer; consultancy: Roche, Biomarin; data monitoring committee: Vertex.

Off-label drug use

Parul Rai: nothing to disclose.

Kenneth I. Ataga: nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010; 376(9757):2018-2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, et al.. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):142-151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61229-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranque B, Kitenge R, Ndiaye DD, et al.. Estimating the risk of child mortality attributable to sickle cell anaemia in sub-Saharan Africa: a retrospective, multicentre, case-control study. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(3):e208-e216. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Telfer P, Coen P, Chakravorty S, et al.. Clinical outcomes in children with sickle cell disease living in England: a neonatal cohort in East London. Haematologica. 2007;92(7):905-912. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, et al.. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(23):1639-1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmariah H, Garrett ME, De Castro LM, et al.. Factors associated with survival in a contemporary adult sickle cell disease cohort. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(5):530-535. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maitra P, Caughey M, Robinson L, et al.. Risk factors for mortality in adult patients with sickle cell disease: a meta-analysis of studies in North America and Europe. Haematologica. 2017;102(4):626-636. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.153791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBaun MR, Ghafuri DL, Rodeghier M, et al.. Decreased median survival of adults with sickle cell disease after adjusting for left truncation bias: a pooled analysis. Blood. 2019;133(6):615-617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-880575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunn HF. Pathogenesis and treatment of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):762-769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Rev. 2007;21(1):37-47. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, et al.. Sickle cell disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;15(4):18010. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton WA, Bunn HF. Treating sickle cell disease by targeting HbS polymerization. Blood. 2017;129(20):2719-2726. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-765891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, et al; Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1317-1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang WC, Ware RE, Miller ST, et al; BABY HUG Investigators. Hydroxycarbamide in very young children with sickle-cell anaemia: a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (BABY HUG). Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1663-1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, et al.. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA. 2014;312(10):1033-1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Montalembert M, Voskaridou E, Oevermann L, et al; All ESCORT HU Investigators. Real-life experience with hydroxyurea in patients with sickle cell disease: results from the prospective ESCORT-HU cohort study. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(10):1223-1231. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hankins JS, McCarville MB, Rankine-Mullings A, et al.. Prevention of conversion to abnormal transcranial Doppler with hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia: a phase III international randomized clinical trial. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(12):1099-1105. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware RE, Davis BR, Schultz WH, et al.. Hydroxycarbamide versus chronic transfusion for maintenance of transcranial doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anaemia—TCD with transfusions changing to hydroxyurea (TWiTCH): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10019):661-670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tshilolo L, Tomlinson G, Williams TN, et al; REACH Investigators. Hydroxyurea for children with sickle cell anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(2):121-131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdullahi SU, Jibir BW, Bello-Manga H, et al.. Hydroxyurea for primary stroke prevention in children with sickle cell anaemia in Nigeria (SPRING): a double-blind, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(1):e26-e37. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00368-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeBaun MR, Jordan LC, King AA, et al.. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrovascular disease in children and adults. Blood Adv. 2020;4(8):1554-1588. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oksenberg D, Dufu K, Patel MP, et al.. GBT440 increases haemoglobin oxygen affinity, reduces sickling and prolongs RBC half-life in a murine model of sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2016;175(1):141-153. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vichinsky E, Hoppe CC, Ataga KI, et al; HOPE Trial Investigators. A phase 3 randomized trial of voxelotor in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(6):509-519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estepp JH, Kalpatthi R, Woods G, et al.. Safety and efficacy of voxelotor in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease aged 4 to 11 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(8):e29716. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ataga KI, Reid M, Ballas SK, et al; ICA-17043-10 Study Investigators. Improvements in haemolysis and indicators of erythrocyte survival do not correlate with acute vaso-occlusive crises in patients with sickle cell disease: a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the Gardos channel blocker senicapoc (ICA-17043). Br J Haematol. 2011;153(1):92-104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brousseau DC, Scott JP, Badaki-Makun O, et al; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). A multicenter randomized controlled trial of intravenous magnesium for sickle cell pain crisis in children. Blood. 2015;126(14):1651-1657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-05-647107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niihara Y, Miller ST, Kanter J, et al; Investigators of the phase 3 trial of l-glutamine in sickle cell disease. A phase 3 trial of l-glutamine in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):226-235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sins JWR, Fijnvandraat K, Rijneveld AW, et al.. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on pain in daily life in patients with sickle cell disease: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(3):444-448. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ataga KI, Kutlar A, Kanter J, et al.. Crizanlizumab for the prevention of pain crises in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):429-439. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novartis AG. Novartis provides update on Phase III STAND trial assessing crizanlizumab. https://www.novartis.com/news/novartis-provides-update-phase-iii-stand-trial-assessing-crizanlizumab. Accessed 9 October 2023.

- 31.Telen MJ, Wun T, McCavit TL, et al.. Randomized phase 2 study of GMI-1070 in SCD: reduction in time to resolution of vaso-occlusive events and decreased opioid use. Blood. 2015;125(17):2656-2664. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-583351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dampier CD, Telen MJ, Wun T, et al; RESET Investigators. A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of rivipansel for sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis. Blood. 2023;141(2):168-179. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biemond BJ, Tombak A, Kilinc Y, et al.. Efficacy and safety of sevuparin, a novel non-anti-coagulant heparinoid, in patients with acute painful vaso-occlusive crisis; a global, multicenter double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled phase-2 trial (TVOCO1). Blood. 2019;134(suppl 1):614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-124653.31270104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orringer EP, Casella JF, Ataga KI, et al.. Purified poloxamer 188 for treatment of acute vaso-occlusive crisis of sickle cell disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(17):2099-2106. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casella JF, Kronsberg SS, Gorney RT. Poloxamer 188 vs placebo for painful vaso-occlusive episodes in children and adults with sickle cell disease-reply. JAMA. 2021;326(10):975-976. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hebbel RP, Osarogiagbon R, Kaul D.. The endothelial biology of sickle cell disease: inflammation and a chronic vasculopathy. Microcirculation. 2004;11(2):129-151. doi: 10.1080/10739680490278402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Field JJ, Majerus E, Gordeuk VR, et al.. Randomized phase 2 trial of regadenoson for treatment of acute vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2017;1(20):1645-1649. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daak AA, Dampier CD, Fuh B, et al.. Double-blind, randomized, multicenter phase 2 study of SC411 in children with sickle cell disease (SCOT trial). Blood Adv. 2018;2(15):1969-1979. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018021444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rees DC, Kilinc Y, Unal S, et al.. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of canakinumab in children and young adults with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2022;139(17):2642-2652. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Field JJ, Kassim A, Brandow A, et al.. Phase 2 trial of montelukast for prevention of pain in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2020;4(6):1159-1165. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gladwin MT, Kato GJ, Weiner D, et al; DeNOVO Investigators. Nitric oxide for inhalation in the acute treatment of sickle cell pain crisis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(9):893-902. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maitre B, Djibre M, Katsahian S, et al.. Inhaled nitric oxide for acute chest syndrome in adult sickle cell patients: a randomized controlled study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(12):2121-2129. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onalo R, Cooper P, Cilliers A, et al.. Randomized control trial of oral arginine therapy for children with sickle cell anemia hospitalized for pain in Nigeria. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(1):89-97. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Machado RF, Barst RJ, Yovetich NA, et al; walk-PHaSST Investigators and Patients. Hospitalization for pain in patients with sickle cell disease treated with sildenafil for elevated TRV and low exercise capacity. Blood. 2011;118(4):855-864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-306167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beurling-Harbury C, Schade SG. Platelet activation during pain crisis in sickle cell anemia patients. Am J Hematol. 1989;31(4):237-241. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830310404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inwald DP, Kirkham FJ, Peters MJ, et al.. Platelet and leucocyte activation in childhood sickle cell disease: association with nocturnal hypoxaemia. Br J Haematol. 2000;111(2):474-481. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jakubowski JA, Zhou C, Jurcevic S, et al.. A phase 1 study of prasugrel in patients with sickle cell disease: effects on biomarkers of platelet activation and coagulation. Thromb Res. 2014;133(2):190-195. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SP, Ataga KI, Orringer EP, Phillips DR, Parise LV. Biologically active CD40 ligand is elevated in sickle cell anemia: potential role for platelet-mediated inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(7):1626-1631. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000220374.00602.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wun T, Paglieroni T, Rangaswami A, et al.. Platelet activation in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 1998;100(4):741-749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cabannes R, Lonsdorfer J, Castaigne JP, Ondo A, Plassard A, Zohoun I.. Clinical and biological double-blind-study of ticlopidine in preventive treatment of sickle-cell disease crises. Agents Actions Suppl. 1984;15:199-212. PMID: 6385647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heeney MM, Hoppe CC, Abboud MR, et al; DOVE Investigators. A multinational trial of prasugrel for sickle cell vaso-occlusive events. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):625-635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heeney MM, Abboud MR, Githanga J, et al.. Ticagrelor vs placebo for the reduction of vaso-occlusive crises in pediatric sickle cell disease: the HESTIA3 study. Blood. 2022;140(13):1470-1481. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qari MH, Aljaouni SK, Alardawi MS, et al.. Reduction of painful vaso- occlusive crisis of sickle cell anaemia by tinzaparin in a double-blind randomized trial. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98(08):392-396. doi: 10.1160/th06-12-0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson A, El Rassi F, DeBaun MR, et al.. Interim analysis of a phase 2 trial to assess the efficacy and safety of crizanlizumab in sickle cell disease patients with priapism (SPARTAN). Blood. 2022;140(suppl 1):1636-1638. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-157004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanter J, Brown RC, Norris C, et al.. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and efficacy of crizanlizumab in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2023;7(6):943-952. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matthew MH, Rees DC, De Montalembert M, et al.. Initial safety and efficacy results from the phase II, multicenter, open-label solace-kids trial of crizanlizumab in adolescents with sickle cell disease (SCD). Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-144730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benjamin LJ, Berkowitz LR, Orringer E, et al.. A collaborative, double-blind randomized study of cetiedil citrate in sickle cell crisis. Blood. 1986;67(5):1442-1447. doi: 10.1182/blood.v67.5.1442.bloodjournal6751442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gillette PN, Peterson CM, Lu YS, Cerami A.. Sodium cyanate as a potential treatment for sickle-cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1974;290(12):654-660. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197403212901204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griffin TC, McIntire D, Buchanan GR. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone therapy for pain in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(11):733-737. doi: 10.1056/nejm199403173301101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weiner DL, Hibberd PL, Betit P, Cooper AB, Botelho CA, Brugnara C.. Preliminary assessment of inhaled nitric oxide for acute vaso-occlusive crisis in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2003;289(9):1136. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morris CR, Kuypers FA, Lavrisha L, et al.. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of arginine therapy for the treatment of children with sickle cell disease hospitalized with vaso-occlusive pain episodes. Haematologica. 2013;98(9):1375-1382. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.086637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rai P, Ataga KI. Drug therapies for the management of sickle cell disease. F1000Res. 2020. Jun 11;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-592. eCollection 2020. PMID: 32765834. doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.22433.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]