Abstract

Avoidance stress coping, defined as persistent internal and/or external avoidance of stress-related stimuli, is a key feature of anxiety- and stress-related disorders, and contributes to increases in alcohol misuse after stress exposure. Previous work using a rat model of predator odor stress avoidance identified corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) signaling via CRF Type 1 receptors (CRF1) in the CeA, as well as CeA projections to the lateral hypothalamus (LH) as key mediators of conditioned avoidance of stress-paired contexts and/or increased alcohol drinking after stress. Here, we report that CRF1-expressing CeA cells that project to the LH are preferentially activated in male and female rats that show persistent avoidance of predator odor stress-paired contexts (termed Avoider rats), and that chemogenetic inhibition of these cells rescues stress-induced increases in anxiety-like behavior and alcohol self-administration in male and female Avoider rats. Using slice electrophysiology, we found that prior predator odor stress exposure blunts inhibitory synaptic transmission and increases synaptic drive in CRF1 CeA-LH cells. In addition, we found that CRF bath application reduces synaptic drive in CRF1 CeA-LH cells in Non-Avoiders only. Collectively, these data show that CRF1 CeA-LH cells contribute to stress-induced increases in anxiety-like behavior and alcohol self-administration in male and female Avoider rats.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Stress may lead to a variety of behavioral and physiological negative consequences, and better understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms that contribute to negative stress effects may lead to improved prevention and treatment strategies. This study, performed in laboratory rats, shows that animals that exhibit avoidance stress coping go on to develop heightened anxiety-like behavior and alcohol self-administration, and that these behaviors can be rescued by inhibiting the activity of a specific population of neurons in the central amygdala. This study also describes stress-induced physiological changes in these neurons that may contribute to their role in promoting increased anxiety and alcohol self-administration.

Keywords: alcohol, stress, anxiety, central amygdala, corticotropin-releasing factor

Introduction

Exposure to stressful events may lead to long-lasting negative consequences depending on the type of coping mechanism engaged during stress (Holahan et al., 2005). Avoidance stress coping, defined as a form of persistent external (physical) and/or internal (mental) avoidance of stress-related stimuli, is a key feature of anxiety disorder (Arnaudova et al., 2017) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Bryant and Harvey, 1995), and is linked to negative consequences, such as alcohol misuse (Hruska et al., 2023). There is a critical need for better understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of avoidance coping after stress, as well as other behaviors that are exhibited by individuals that exhibit avoidance stress coping phenotypes.

The use of animal models to investigate the neurobiological underpinnings of the negative consequences of stress is critical for the development of better prevention, diagnostic, and treatment strategies. Our laboratory uses a rat model in which a subset of animals exposed to predator odor stress (bobcat urine) show persistent and stable avoidance of predator odor-paired contexts, reminiscent of avoidance behavior in subpopulations of humans who have experienced stressful events. Avoidance of stress-paired contexts in this model is not attributable to nonspecific factors, such as learning or detection of the predator odor (for review, see Albrechet-Souza and Gilpin, 2019). Similar to reports in humans, Avoider rats exhibit increases in alcohol drinking relative to Non-Avoiders and unstressed controls (Edwards et al., 2013; Weera et al., 2020). Using this animal model, we have identified various neurobiological processes that may contribute to avoidance stress coping and/or related behavioral phenomena. For example, we reported predator odor stress effects in the paraventricular hypothalamus (Whitaker and Gilpin, 2015), ventromedial PFC (Schreiber et al., 2017), dorsal hippocampus (Kelley et al., 2023), and CeA (Itoga et al., 2016; Weera et al., 2020, 2021), and some of these effects are observed only in Avoider or Non-Avoider rats.

The CeA is a GABAergic nucleus that consists of interneurons and projection neurons that express a variety of neuropeptides and neuropeptide receptors (Swanson and Petrovich, 1998). The CeA is a major output nucleus of the amygdala and is an important modulator of behavioral and physiological stress responses (Ventura-Silva et al., 2013). We previously reported that predator odor stress induces greater c-Fos expression in the CeA (Weera et al., 2020, 2021), and increases corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) peptide content (Itoga et al., 2016) and immunoreactivity (Weera et al., 2020) in the CeA of Avoider rats. We also reported that antagonism of CRF Type 1 receptors (CRF1) in the CeA attenuates post-stress increases in alcohol drinking and avoidance behavior in Avoider rats (Weera et al., 2020). Among the many brain regions that receive CeA outputs is the lateral hypothalamus (LH) (Krettek and Price, 1978). We recently reported that CeA projections to LH are critical mediators of avoidance behavior after stress (Weera et al., 2021), and that many of these LH-projecting CeA cells express Crhr1 mRNA, which encodes CRF1 (Weera et al., 2021). Given that (1) intra-CeA CRF1 blockade attenuates avoidance and normalizes alcohol drinking in Avoider rats, (2) CeA-LH cell inhibition attenuates avoidance in Avoider rats, and (3) a subset of CeA-LH cells express CRF1, we hypothesized that stress-induced increases in alcohol drinking and avoidance-related behaviors in Avoider rats are mediated by LH-projecting CeA cells that express CRF1 (CRF1 CeA-LH cells).

The main goal of this study was to test the hypotheses that predator odor stress activates CRF1 CeA-LH cells in Avoider rats, and that CRF1 CeA-LH cell inhibition rescues stress-induced increases in alcohol drinking and avoidance-related behaviors in Avoider rats, using male and female CRF1-Cre rats (Weera et al., 2022). We also sought to characterize the electrophysiological properties of these cells in stressed and unstressed rats.

Materials and Methods

General materials and methods

Subjects

All experiments were conducted in adult male and female transgenic CRF1-Cre-tdTomato rats on a Wistar background that were generated in our laboratory (Weera et al., 2022). These rats are bred and maintained by our laboratory at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center–New Orleans (LSUHSC-NO). Experiments 1, 2, and 5 were conducted at the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System, and Experiments 3 and 4 were conducted at LSUHSC-NO. All rats were pair-housed in humidity- and temperature-controlled (22°C) vivaria on a reverse 12 h light/dark cycle, and had ad libitum access to food and water. All behavioral procedures occurred in the dark phase under red or dim light illumination. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of LSUHSC-NO and Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System, and were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Drugs

We used the designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drug (DREADD) actuator, JHU37160 (Bonaventura et al., 2019) (Hello Bio, catalog #HB6261), which was prepared in sterile saline to a working concentration of 1 mm. CRF (Tocris, catalog #1151) was dissolved in the circulating aCSF during electrophysiological recordings to a working concentration of 50 nm.

Stereotaxic surgeries

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and mounted into a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments) for all stereotaxic surgeries. The following coordinates (from bregma) were used for bilateral intra-LH or CeA microinjections: −2.1 mm posterior, ±2.0 mm lateral, and −8.8 mm ventral (LH) or −2.5 mm posterior, ±4.0 mm lateral, and −8.4 mm ventral (CeA). Retrobeads (Lumafluor), Cholera Toxin B (Fisher Scientific), or viral constructs (see below) were injected into each side of the LH or CeA at a volume of 0.5 µl over 5 min, and injectors were left in place for an additional 2 min. Viral titers were between 1.0 and 1.5 × 1013 GC/ml. For bilateral cannula implants targeting the LH, custom-made 26 gauge bilateral cannulae (Plastics One) were targeted to 1 mm above the LH (−2.1 mm posterior, ±2.0 mm lateral, and −7.8 mm ventral) and were secured in place using dental cement anchored to the skull with metal screws. At the end of the surgery, internal cannulae and screw caps were used to prevent clogging of the implanted cannulae. All rats were monitored at the end of surgeries to ensure recovery from anesthesia and were given at least 7 d to recover before the start of behavioral procedures. Rats were treated with the analgesic flunixin (2.5 mg/kg, s.c.) and the antibiotic cefazolin (20 mg/kg, i.m.) before the start of surgeries and once the following day.

Predator odor place conditioning

Predator odor place conditioning was performed as previously described (Edwards et al., 2013). The apparatus consists of two conditioning chambers with distinct tactile (hole or mesh floors) and visual stimuli (circles or white walls) separated by a small center chamber. On day 1, rats were allowed to freely explore the apparatus for 5 min, and time spent in each chamber was recorded as Pretest Time. Rats were assigned to Stress or Unstressed Control groups, counterbalanced for the magnitude of Pretest Time. On day 2, rats were confined to one chamber for 15 min in the absence of odor (Neutral Conditioning). On day 3, rats were confined to the other chamber for 15 min in the presence of predator odor (a paper towel soaked with bobcat urine placed under the floor; Maine Outdoor Solutions). Chamber assignments were done in a counterbalanced fashion (i.e., unbiased design). On day 4, rats were again allowed to freely explore the two conditioning chambers for 5 min, and time spent in each chamber was recorded as Post-test Time. Time spent in the odor-paired chamber during Post-test minus Pretest was used to index for avoidance. Rats that showed a >10 s decrease in time spent on the odor-paired chamber were classified as Avoiders, and all other stressed rats were classified as Non-Avoiders (Fig. 1A, inset). Unstressed Controls were subjected to the 4 d procedure but never exposed to predator odor.

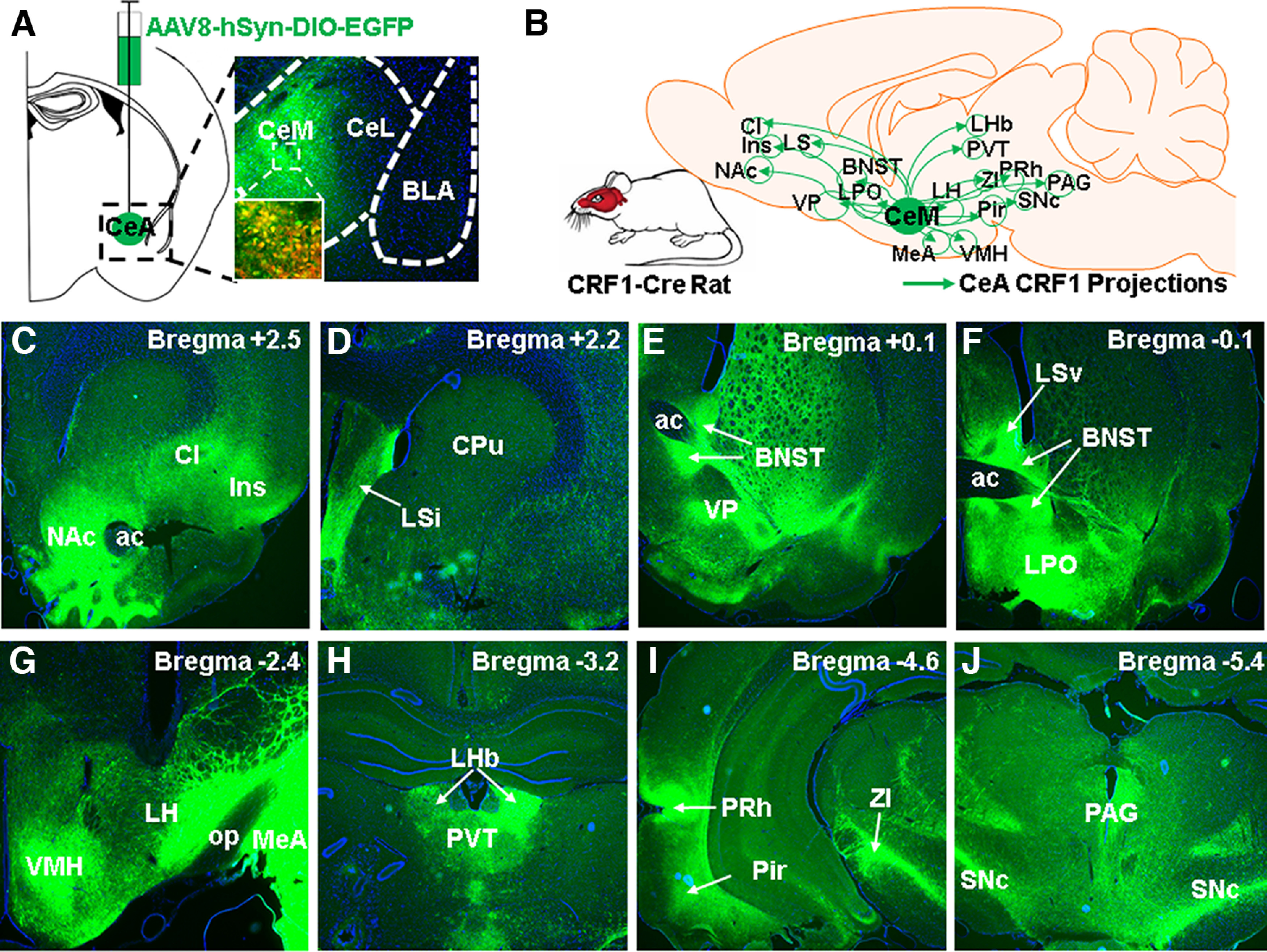

Figure 1.

CeA CRF1 cells project to various brain areas throughout the brain. A, Image of virally targeted EGFP expression in CeA CRF1 cells. Inset, Zoomed in image showing colocalization between EGFP+ and tdTomato+ (CRF1+) cell bodies in CeA. B, Summary schematic of brain areas that receive CeA CRF1 projections (EGFP fibers). C–J, Images of EGFP fibers in various brain areas throughout the brain. Cl: claustrum; Ins: Insula; NAc: nucleus accumbens; LS: lateral septum; VP: ventral pallidum; BNST: bed nucleus of stria terminalis; LPO: lateral preoptic area; MeA: medial amygdala; VMH: ventromedial hypothalamus; Pir: piriform cortex; ZI: zona incerta; PRh: perirhinal cortex; PVT: paraventricular thalamus; SNc: substantia nigra pars compacta; PAG: periaqueductal gray.

Immunohistochemistry

Rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and were transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS followed by 4% PFA. Brains were extracted and postfixed in 4% PFA for 24 h (at 4°C), cryoprotected in 20% sucrose for 48-72 h (at 4°C), and snap-frozen in 2-methylbutane on dry ice. Coronal sections (40 µm) were collected using a cryostat and stored in PBS with 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C. Four sections from each brain, separated by ∼200 µm, were processed for c-Fos immunohistochemistry. Sections were washed 3 × 10 min in PBS and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. Sections were then washed 3 × 10 min in PBS and incubated in a blocking buffer containing 1% (w/v) BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Then, sections were incubated in a rabbit anti-c-Fos antibody (Abcam, catalog #ab190289; 1:3000 in blocking buffer) for 48 h at 4°C. Sections were then washed for 10 min in TNT buffer (0.1 m Tris base in saline with 0.3% Triton X-100), incubated for 30 min in 0.5% (w/v) Tyramide Signal Amplification blocking reagent (see below) in 0.1 m Tris base, and incubated for 30 min in ImmPRESS HRP anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories, catalog #MP-7401) at room temperature. Following 4 × 5 min washes in TNT buffer, sections were incubated in Cyanine 5 (1:50 in Tyramide Signal Amplification diluent; Akoya Biosciences, catalog #NEL745001KT) for 10 min at room temperature. Sections were washed 3 × 10 min in TNT buffer and mounted on microscope slides with Fluoro-Gel II with DAPI (Electron Microscopy Sciences, catalog #17985-51). All imaging was done using a Keyence BZ-X800 fluorescence microscope.

Slice electrophysiology

On the day of slice electrophysiology experiments, rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused with 80 ml room temperature (∼25°C) N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG) aCSF containing the following (in mm): 92 NMDG, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 25 glucose, 2 thiourea, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 MgSO4·7 H2O, 5 Na-ascorbate, and 3 Na-pyruvate; 300-μm-thick coronal sections containing the CeA were collected using a vibratome (VT1200S, Leica Microsystems). Sections were incubated in NMDG aCSF at 36°C for 12 min, then transferred to a room temperature holding aCSF solution containing the following (in mm): 92 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 25 glucose, 2 thiourea, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgSO47·H2O, 5 Na-ascorbate, and 3 Na-pyruvate. Brain sections were allowed to rest ∼45 min before commencement of the recording session. At the time of recording, sections were transferred to a recording aCSF solution containing the following (in mm): 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.5 MgSO4·7 H2O, 24 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose (Avegno et al., 2018). Recording aCSF was maintained at 31°C-33°C using an inline heater (Warner Instruments). Recordings were performed with an internal recording solution containing the following (in mm): 120 K-gluconate, 4 KCl, 2 K-EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na2-GTP, and 10 Na2-phosphocreatine, pH 7.2-7.3 (285-295 mOsm) (Mayeux et al., 2017; Weera et al., 2021).

Experimental procedures

Experiment 1

Using a combination of cholera toxin B retrograde tracing and RNAscope labeling, we previously showed that a subset of LH-projecting CeA cells were positive for Crhr1 mRNA (Weera et al., 2021). The purpose of this experiment was to confirm that CeA CRF1 neurons project to the LH using a genetic approach (CRF1-Cre rats). CRF1-Cre rats (n = 2 males and 2 females) were given intra-CeA injections of a Cre-dependent anterograde EGFP virus (AAV8-hSyn-DIO-EGFP) and were perfused for histologic analysis. We collected 40 µm coronal sections throughout the brain (∼ bregma 5.5 to −5.5) and mounted them onto microscope slides with Fluoro-Gel II containing DAPI (Electron Microscopy Sciences, catalog #17985-51). We then looked for EGFP-labeled fibers in the LH, as well as throughout the brain using a Keyence BZ-X800 fluorescence microscope and constructed a map that summarizes the brain regions in which EGFP-labeled fibers were found (see Fig. 1).

Experiment 2

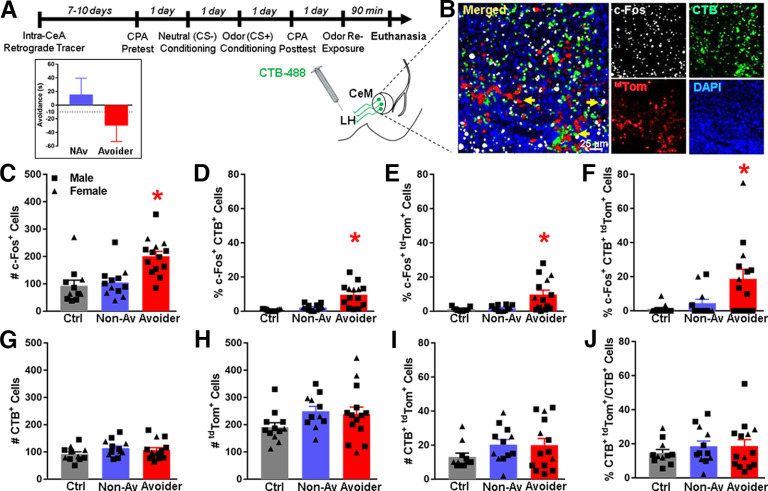

The purpose of this experiment was to test the hypothesis that Avoider rats have more c-Fos+ CRF1 CeA-LH cells than Non-Avoiders following predator odor stress. CRF1-Cre-tdTomato rats were given intra-LH injections of a retrograde tracer (cholera toxin B, CTB-488) and were allowed to recover for 7-10 d. Subsequently, rats were subjected to the predator odor place conditioning procedure described above. One day after Post-test (i.e., avoidance test), rats were re-exposed to predator odor and killed 90 min later for c-Fos immunohistochemistry as described above (for timeline schematic, see Fig. 2A). The total numbers of c-Fos+, CTB+, and CRF1+ (tdTomato+) cells in the CeA were quantified by a research assistant who was blinded to experimental conditions. The number of c-Fos/CTB and c-Fos/tdTomato double-labeled cells, as well as c-Fos/CTB/tdTomato triple-labeled cells were also quantified. These colabeled cells were analyzed as % c-Fos+ CTB+ cells (calculated as number of c-Fos+/CTB+ double-labeled cells over total number of CTB+ cells), % c-Fos+ tdTomato+ (calculated as number of c-Fos+/tdTomato+ double-labeled cells over total number of tdTomato+ cells), and % c-Fos+ CTB+ tdTomato+ cells (calculated as number of triple-labeled cells over total number of tdTomato+/CTB+ double-labeled cells).

Figure 2.

Stress-exposed Avoider rats have more c-Fos+ CRF1 CeA-LH cells than Non-Avoiders and unstressed Controls. A, Timeline schematic of Experiment 1. Inset, Predator odor CPA scores (time in odor-paired chamber during post-test minus pretest) for Avoiders and Non-Avoiders. B, Representative images of c-Fos+ (pseudo white), CRF1+ (tdTomato+, red), and LH-projecting (CTB+, green) cells within the CeA. Yellow arrows indicate triple-labeled (c-Fos+, tdTomato+, CTB+) cells. C, Total number of CeA c-Fos+ cells in Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and unstressed Controls. D, Percent CeA c-Fos and CTB double-positive cells, (E) percent CeA c-Fos and tdTomato double-positive cells, and (F) percent c-Fos, CTB, and tdTomato triple-positive cells in Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and unstressed Controls. *Significant difference versus Non-Avoider and Control groups following one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc tests (exact p values reported in the text). G, Total number of CTB+ and (H) tdTomato+ cells in CeA of Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls. I, Total number and (J) percentage of CTB and tdTomato double-positive (LH-projecting CRF1) cells in CeA of Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls. Data are shown collapsed by sex; male data points are represented by square symbols (Controls, n = 7; Non-Avoiders, n = 7; Avoiders, n = 11), and female data points are represented by triangle symbols (Controls, n = 4; Non-Avoiders, n = 5, Avoiders, n = 3).

Experiment 3

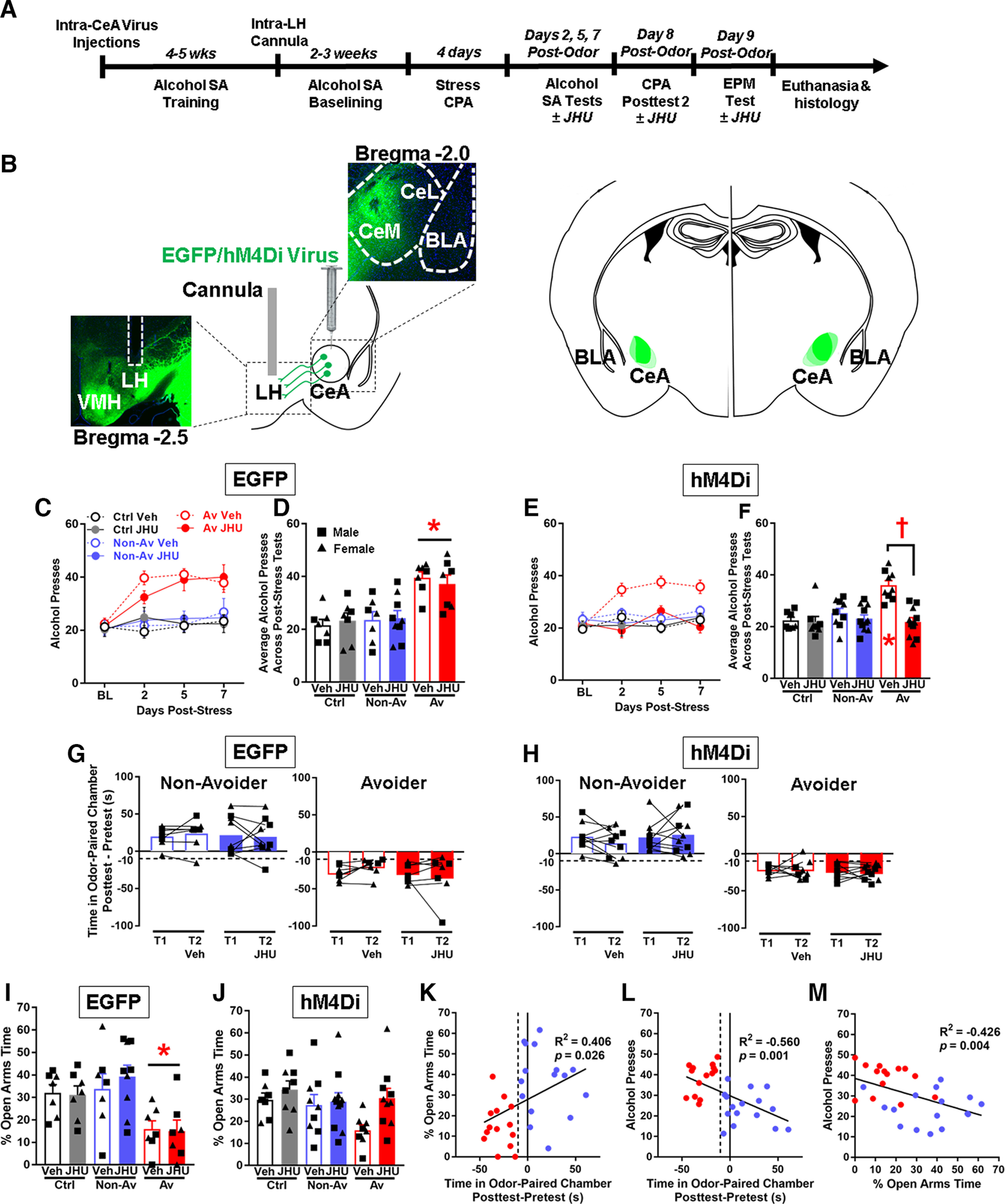

The purpose of this experiment was to test the hypothesis that inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells rescues stress-enhanced alcohol self-administration in Avoider rats (for timeline of this experiment, see Fig. 3A). CRF1-Cre-tdTomato rats were given intra-CeA injections of AAV8-hSyn-DIO-HA-hM4Di-IRES-mCitrine (Addgene, catalog #50455-AAV8) or AAV8-hSyn-DIO-EGFP (Addgene, catalog #50457-AAV8) to target an inhibitory DREADD receptor or control fluorophore to CeA CRF1 cells in a Cre-dependent manner (see Fig. 3B) and were given at least 7 d to recover. Virus group assignment was done in an alternating and counterbalanced fashion. Subsequently, rats were trained to self-administer 10% alcohol as previously described (Schreiber et al., 2017). Upon stabilization of operant responding for alcohol in 30 min sessions on a Monday-Wednesday-Friday schedule (4-5 weeks from onset of operant training), rats were implanted with bilateral cannulae targeting the LH (see Stereotaxic surgeries) and were given at least 7 d to recover. Rats were re-exposed to 30 min alcohol self-administration sessions for 3 weeks. In week 3, rats were given sham intra-LH injections on Monday and Wednesday 30 min before alcohol self-administration sessions to habituate them to the procedure. On Friday, rats were given intra-LH injections of Vehicle 30 min before the operant session and operant responding during this session was recorded as the Pre-Stress Baseline. Subsequently, rats were exposed to predator odor place conditioning and indexed for avoidance as described above. On days 2, 5, and 7 following predator odor exposure, rats were given 30 min alcohol self-administration testing sessions that were preceded by intra-LH infusions of a DREADD receptor agonist, JHU37160 (1 mm, 300 nl/side at a rate of 150 nl/min; JHU) (Bonaventura et al., 2019) or Vehicle (Veh) 30 min before the start of operant sessions. Drug treatment groups were counterbalanced based on pre-stress baseline operant responding. On the day after the last alcohol self-administration session (day 8 after odor exposure), rats were re-indexed for avoidance following a 30 min intra-LH pretreatment of JHU or Veh. On the following day (day 9 after odor exposure), rats were tested for anxiety-like behavior using the elevated plus maze (EPM) 30 min following intra-LH pretreatment of JHU or Veh. At the end of the experiment, rats were perfused with 4% PFA, brains were postfixed and sectioned at 40 µm, and cannula placements were confirmed histologically using a Keyence BZ-X800 fluorescence microscope (see Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Chemogenetic inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells normalizes post-stress alcohol self-administration and anxiety-like behavior in Avoider rats. A, Timeline schematic of Experiment 3. B, Left, Schematic of intra-CeA virus injection and representative images of CeA virus expression and LH cannula placement. Right, Schematic of virus expression for all subjects. C, Number of alcohol lever presses during pre-stress baseline and on days 2, 5, and 7 post-stress (30 min self-administration sessions) by Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and unstressed Controls that were given intra-CeA EGFP virus. D, Average number of alcohol lever presses across days 2, 5, and 7 post-stress by Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls (EGFP group). *Significant difference versus Non-Avoider and Control groups, respectively, following two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc tests. E, Number of alcohol lever presses during pre-stress baseline and on days 2, 5, and 7 post-stress by Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and unstressed Controls that were given intra-CeA hM4Di virus. F, Average number of alcohol lever presses across days 2, 5, and 7 post-stress by Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls (hM4Di group). *Significant difference between the Avoider Veh group versus Non-Avoider and Controls Veh groups following two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc tests. †Significant difference between the Avoider Veh versus JHU groups. G, Predator odor CPA scores (time spent in the odor-paired chamber Post-test minus Pretest) across Post-tests 1 and 2 in Avoiders and Non-Avoiders in the EGFP and (H) hM4Di groups following Veh or JHU treatment. I, Percent time spent in the open arms of the EPM in the EGFP and (J) hM4Di groups following Veh or JHU treatment. In the EGFP group (I): *Significant difference between Avoiders versus Non-Avoiders and Controls following two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc tests (no effect of Veh/JHU treatment). K, Correlation between % open arms times during EPM testing and predator odor CPA scores. L, Correlation between alcohol presses and predator odor CPA scores. M, Correlation between alcohol presses and % open arms times during EPM testing. Data are shown collapsed by sex; male data points are represented by square symbols (EGFP: Controls, n = 6; Non-Avoiders, n = 8; Avoiders, n = 7; hM4Di: Controls, n = 9; Non-Avoiders, n = 10; Avoiders, n = 9), and female data points are represented by triangle symbols (EGFP: Controls, n = 8; Non-Avoiders, n = 8; Avoiders, n = 7; hM4Di: Controls, n = 6; Non-Avoiders, n = 10; Avoiders, n = 10).

Experiment 4

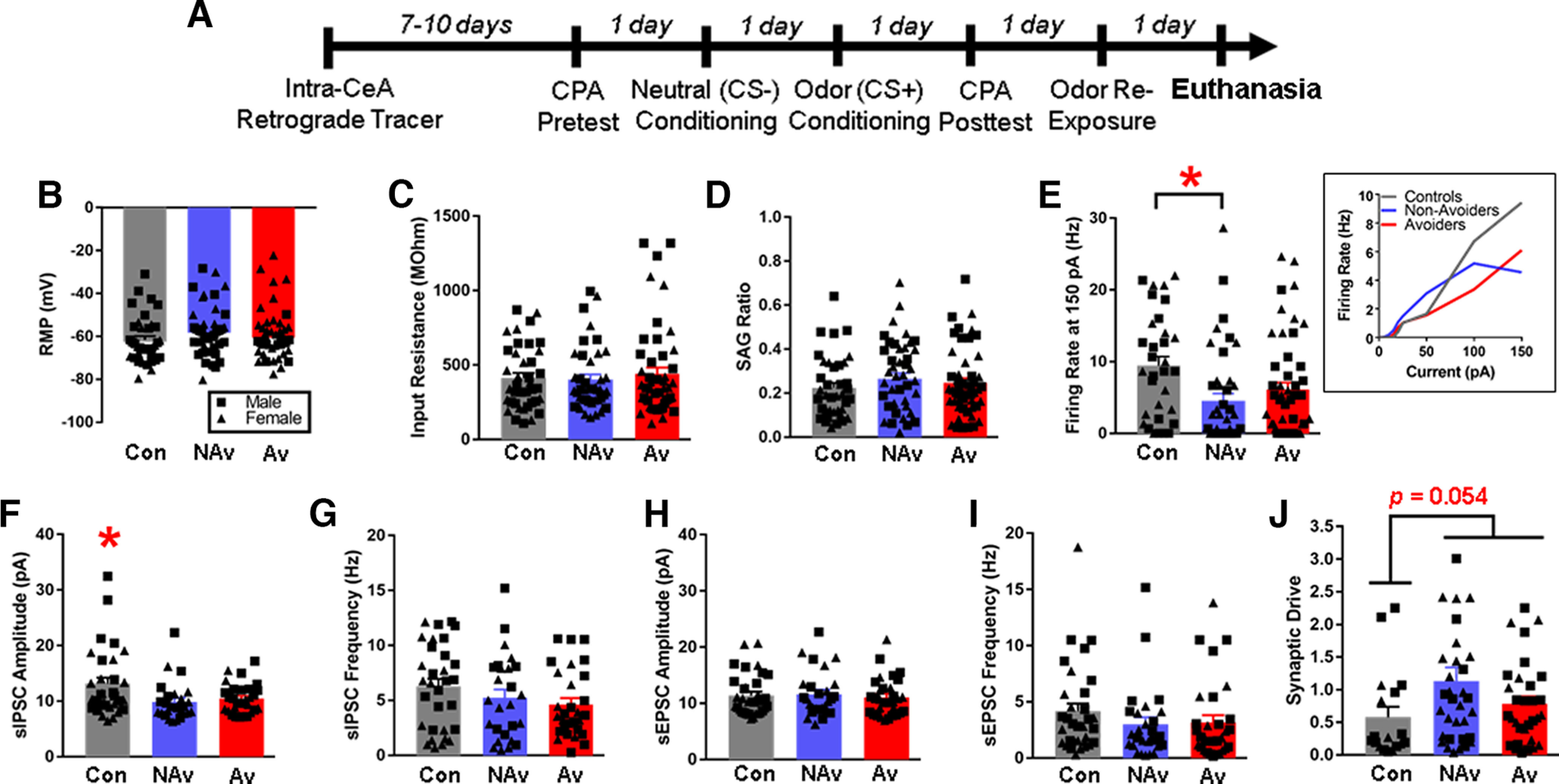

The purpose of this experiment was to measure the intrinsic properties and spontaneous synaptic transmission in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls using ex vivo slice electrophysiology. Rats were given intra-LH injections of a retrograde tracer (green Retrobeads, Lumafluor) and were allowed to recover for 7-10 d. The timeline of this experiment is identical to Experiment 1, except that rats were killed for slice electrophysiology on the next day after stress re-exposure (for timeline schematic, see Fig. 4A). We measured the following intrinsic neuronal excitability properties: resting membrane potential, input resistance, voltage SAG, and firing rate to input current response (Dembrow et al., 2010; Joshi et al., 2015; Weera et al., 2021). We also recorded sIPSC events while clamping the membrane voltage at −50 mV and sEPSCs while clamping the membrane voltage at −70 mV.

Figure 4.

CRF1 CeA-LH cells in stressed and unstressed rats show differences in intrinsic excitability and synaptic transmission. A, Timeline schematic of Experiment 3. B, Resting membrane potential. C, Input resistance. D, SAG ratio. E, Firing rate at 150 pA (inset, F-I curves). F, sIPSC amplitude. G, sIPSC frequency. H, sEPSC amplitude. I, sEPSC frequency. J, Synaptic drive. *Significant difference between Controls versus Non-Avoiders in E, between Controls versus Non-Avoiders and Avoiders, respectively, in F, and between Controls versus both Avoiders and Non-Avoiders combined in J. Data are shown collapsed by sex; male data points are represented by square symbols (Controls, n = 22 cells; Non-Avoider, n = 15 cells; Avoider, n = 22 cells), and female data points are represented by triangle symbols (Controls, n = 15 cells; Non-Avoider, n = 25 cells; Avoider, n = 24 cells).

Experiment 5

The purpose of this experiment was to test the effect of CRF on spontaneous inhibitory and excitatory synaptic transmission in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls. All procedures through death were identical to Experiment 3. Here, we used aCSF bath-applied CRF and compared pre- and post-sEPSC and -sIPSC amplitudes and rates. After baseline measurements were taken, CRF was allowed to circulate for 15 min before spontaneous currents were measured again while clamping the voltage, at −70 and −50 mV, separately.

Statistical analysis

All statistics were analyzed using multifactorial ANOVAs in IBM SPSS version 25. Between-subjects' factors include sex (male, female), stress group (Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, Controls), and JHU treatment (Veh, JHU), where appropriate. Repeated within-subjects' factors include testing time point and CRF treatment (aCSF, CRF), where appropriate. Sex was included as a fixed factor in all analyses. When there were no significant main or interactive effects of sex, analyses were collapsed across both sexes. Specific statistical tests and values are reported in Results. All graphs were made using GraphPad Prism 7.

Results

Experiment 1: CeA CRF1 cells project to the LH and various areas throughout the brain

The purpose of this experiment was to confirm that CeA CRF1 neurons project to the LH using a genetic approach, and to identify additional brain regions that receive projections from CeA CRF1 cells. Anterograde AAV8-hSyn-DIO-EGFP was targeted to CeA CRF1 cells in a Cre-dependent manner (using CRF1-Cre rats; Fig. 1A) and the brain regions that received EGFP-labeled fibers were identified. Figure 1B summarizes the brain regions in which EGFP-labeled fibers from CeA CRF1 cells were found: nucleus accumbens (NAc), insula, claustrum (Fig. 1C), intermediate lateral septal nucleus (Fig. 1D), bed nucleus of stria terminalis, ventral pallidum, ventral lateral septal nucleus, lateral preoptic area (Fig. 1E,F), medial amygdala, LH, ventromedial hypothalamus (Fig. 1G), lateral habenula, paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (Fig. 1H), piriform cortex, perirhinal cortex, zona incerta (Fig. 1I), substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), and periaqueductal gray (Fig. 1J). We did not observe differences in projection targets of CeA CRF1 cells between male and female rats.

Experiment 2: stress-exposed Avoider rats have more c-Fos+ CRF1 CeA-LH cells than Non-Avoiders and unstressed controls

CRF1-Cre-tdTomato rats were given intra-LH injections of a retrograde tracer (CTB-488) and were allowed to recover for 7-10 d. Rats were then exposed to predator odor stress, indexed for avoidance of the stress-paired context, re-exposed to predator odor, and perfused 90 min later (see timeline in Fig. 2A). Predator odor CPA scores for classifying rats as Avoiders versus Non-Avoiders are shown in Figure 2A (inset). Tissue sections containing the CeA were processed for c-Fos immunohistochemistry, and Figure 2B shows representative images of c-Fos+ (white), CRF1+ (tdTomato+, red), and LH-projecting (CTB+, green) cells within the CeA (yellow arrows indicate triple-labeled cells). Because there was no effect of sex on the following outcome measures, all data are analyzed and shown collapsed by sex. Quantification of all c-Fos+ cells within the CeA showed that Avoider rats have more c-Fos+ cells after stress than Non-Avoiders and Controls [Fig. 2C; one-way ANOVA, main effect of stress group (F(2,34) = 11.1, p < 0.001); Tukey's post hoc tests: Avoiders > Controls (p = 0.001), Avoiders > Non-Avoiders (p = 0.002)], a phenomenon that we have previously reported (Weera et al., 2020, 2021). Within the LH-projecting cell population, we found that there were more c-Fos+ LH-projecting (i.e., greater % c-Fos+ CTB+) CeA cells in Avoiders than in Non-Avoiders and Controls [Fig. 2D; one-way ANOVA, main effect of stress group (F(2,34) = 34.5, p < 0.001); Tukey's post hoc tests: Avoiders > Controls (p < 0.001), Avoiders > Non-Avoiders (p = 0.001)], replicating our previously published finding (Weera et al., 2021). Avoider rats also had more c-Fos+ CRF1 (i.e., greater % c-Fos+ tdTomato+) cells in the CeA than Non-Avoiders and Controls [Fig. 2E; one-way ANOVA, main effect of stress group (F(2,34) = 18.6, p = 0.001); Tukey's post hoc tests: Avoiders > Controls (p = 0.003), Avoiders > Non-Avoiders (p = 0.005)]. Finally, in support of our hypothesis, we found that Avoider rats have more c-Fos+ CRF1 CeA-LH (i.e., greater % c-Fos+ CTB+ tdTomato+) cells than Non-Avoiders and Controls [Fig. 2F; one-way ANOVA, main effect of stress group (F(2,34) = 12.4, p = 0.001); Tukey's post hoc tests: Avoiders > Controls (p = 0.009), Avoiders > Non-Avoiders (p = 0.034)]. The numbers of CTB+, tdTomato+, and CTB+ tdTomato+ cells, as well as the percentage of CTB+ tdTomato+/CTB+ cells in the CeA were similar between Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls (Fig. 2G–J).

Experiment 3: chemogenetic inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells normalizes post-stress alcohol self-administration and anxiety-like behavior in avoider rats

The purpose of this experiment was to test the hypothesis that inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells rescues stress-enhanced alcohol self-administration in Avoider rats (see experimental timeline in Fig. 3A and viral approach in Fig. 3B). Inhibitory hM4Di DREADD receptor or EGFP control was targeted to CeA CRF1 cells, and rats were given intra-LH pretreatment of the DREADD agonist JHU37160 or Vehicle before alcohol self-administration testing. In the EGFP control group, Avoiders showed escalated alcohol self-administration across post-stress testing sessions, regardless of JHU or Veh pretreatment [Fig. 3C,D; two-way ANOVA, main effect of stress group (F(2,44) = 18.3, p < 0.001), no stress group × treatment interaction; Tukey's post hoc for stress group: Avoider > Control (p < 0.001), Avoider > Non-Avoider (p < 0.001)]. In the hM4Di group, Avoiders pretreated with Veh showed escalated alcohol self-administration, but not Avoiders treated with JHU [Fig. 3E,F; two-way ANOVA, stress group × treatment interaction (F(2,54) = 8.7, p = 0.001); Tukey's post hoc within Veh treatment group: Avoider > Control (p < 0.001), Avoider > Non-Avoider (p < 0.001); Tukey's post hoc within JHU treatment group: not significant], showing that chemogenetic inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells normalizes escalated alcohol self-administration in Avoider rats. Similarly, a comparison of alcohol self-administration between Veh- and JHU-treated Avoiders shows that JHU-treated Avoiders self-administered less alcohol than Veh-treated Avoiders [Fig. 3F; two-way ANOVA, stress group × treatment interaction (F(2,54) = 8.7, p = 0.001); main effect of treatment within the Avoider stress group (F(1,19) = 28.6, p < 0.001)].

Next, we tested whether inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells alters avoidance of the predator odor-paired chamber (see timeline in Fig. 3A). In the EGFP control group, we found that neither Veh nor JHU treatment altered time spent in the odor-paired chamber (compared with the first avoidance test, Post-test 1) in Avoiders and Non-Avoiders (Fig. 3G). Similarly, in the hM4Di group, neither Veh nor JHU treatment altered time spent in the odor-paired chamber in Avoiders and Non-Avoiders (Fig. 3H).

We subsequently tested whether inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells alters anxiety-like behavior using the EPM test (see timeline in Fig. 3A). In the EGFP control group, Avoiders showed greater anxiety-like behavior (lower % open arms time on the EPM) compared with Non-Avoiders and Controls regardless of Veh or JHU treatment [Fig. 3I; two-way ANOVA, main effect of stress group (F(2,44) = 10.0, p < 0.001), no stress group × treatment interaction; Tukey's post hoc for stress group: Avoider < Control (p = 0.007), Avoider < Non-Avoider (p < 0.001)]. In the hM4Di group, JHU treatment (i.e., chemogenetic inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells) decreased anxiety-like behavior (increased % open arms time) across all stress groups, mainly by normalizing anxiety-like behavior in Avoider rats [Fig. 3J; two-way ANOVA, main effect of treatment (F(1,54) = 4.8, p = 0.034), no stress group × treatment interaction].

We analyzed the relationship between conditioned avoidance of the predator odor-paired chamber and anxiety-like behavior on the EPM, and alcohol drinking in Avoider and Non-Avoider rats using Pearson's correlations. Using data from rats in the EGFP group, we found a significant correlation between predator odor avoidance scores and percent open arms times on the EPM (R2 = 0.406, p = 0.026), such that greater avoidance of the predator odor-paired chamber predicted less time spent in the open arms of the EPM (i.e., greater anxiety-like behavior) after stress (Fig. 3K). In addition, we found a significant inverse correlation between predator odor avoidance scores and the average number of alcohol lever presses across the three post-stress alcohol self-administration sessions (R2 = −0.560, p = 0.001), such that greater avoidance of the predator odor-paired chamber predicted greater alcohol responding (Fig. 3L). Alcohol lever pressing during post-stress alcohol self-administration also correlated inversely with percent open arms times on the EPM (R2 = −0.426, p = 0.004), such that greater alcohol responding after stress predicted less time spent in the open arms of the EPM (i.e., greater anxiety-like behavior) after stress (Fig. 3M).

Experiment 4: CRF1 CeA-LH cells in stressed and unstressed rats show differences in intrinsic excitability and synaptic transmission

To further explore the mechanistic underpinnings of differential recruitment of Non-Avoider versus Avoider CRF1 CeA-LH cells by stress, we performed ex vivo whole-cell slice electrophysiology recordings of CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and unstressed Controls. Figure 4A shows the timeline of this experiment. Under current clamp, we recorded several intrinsic parameters of CRF1 CeA-LH cells. We found no differences in resting membrane potential (Fig. 4B), input resistance (Fig. 4C), or SAG ratio (Fig. 4D) in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls. Recordings of action potential firing in response to step current injection (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 50, 100, 150 pA) revealed that CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Non-Avoiders fired at lower frequencies compared with cells from unstressed Controls at 150 pA [Fig. 4E; one-way ANOVA, F(2124) = 4.7, p = 0.011; Tukey's post hoc: Controls > Non-Avoider (p = 0.008), Controls vs Avoider (not significant)]. There were no differences in action potential firing between Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls at current injections below 150 pA (Fig. 4E, inset).

Recordings of spontaneous IPSCs and EPSCs in voltage clamp mode showed that CRF1 CeA-LH cells from stressed rats (both Avoiders and Non-Avoiders) have lower sIPSC amplitudes compared with Controls [Fig. 4F; one-way ANOVA, F(2,85) = 4.4, p = 0.015; Tukey's post hoc: Controls > Non-Avoiders (p = 0.021), Controls > Avoiders (p = 0.060)]. There were no differences in sIPSC frequencies (Fig. 4G), sEPSC amplitudes (Fig. 4H), and sEPSC frequencies (Fig. 4I) between the groups. We then calculated an overall synaptic drive index for each cell using sEPSC and sIPSC values [synaptic drive = (sEPSC amplitude × frequency)/(sIPSC amplitude × frequency)] and found that CRF1 CeA-LH cells from stressed rats (both Avoiders and Non-Avoiders) have greater synaptic drive compared with unstressed Controls [Fig. 4J; one-way ANOVA, F(2,83) = 3.0, p = 0.054; Tukey's post hoc: not significant; t test between stressed (Avoiders, Non-Avoiders) and unstressed groups: stressed > unstressed (p = 0.054)].

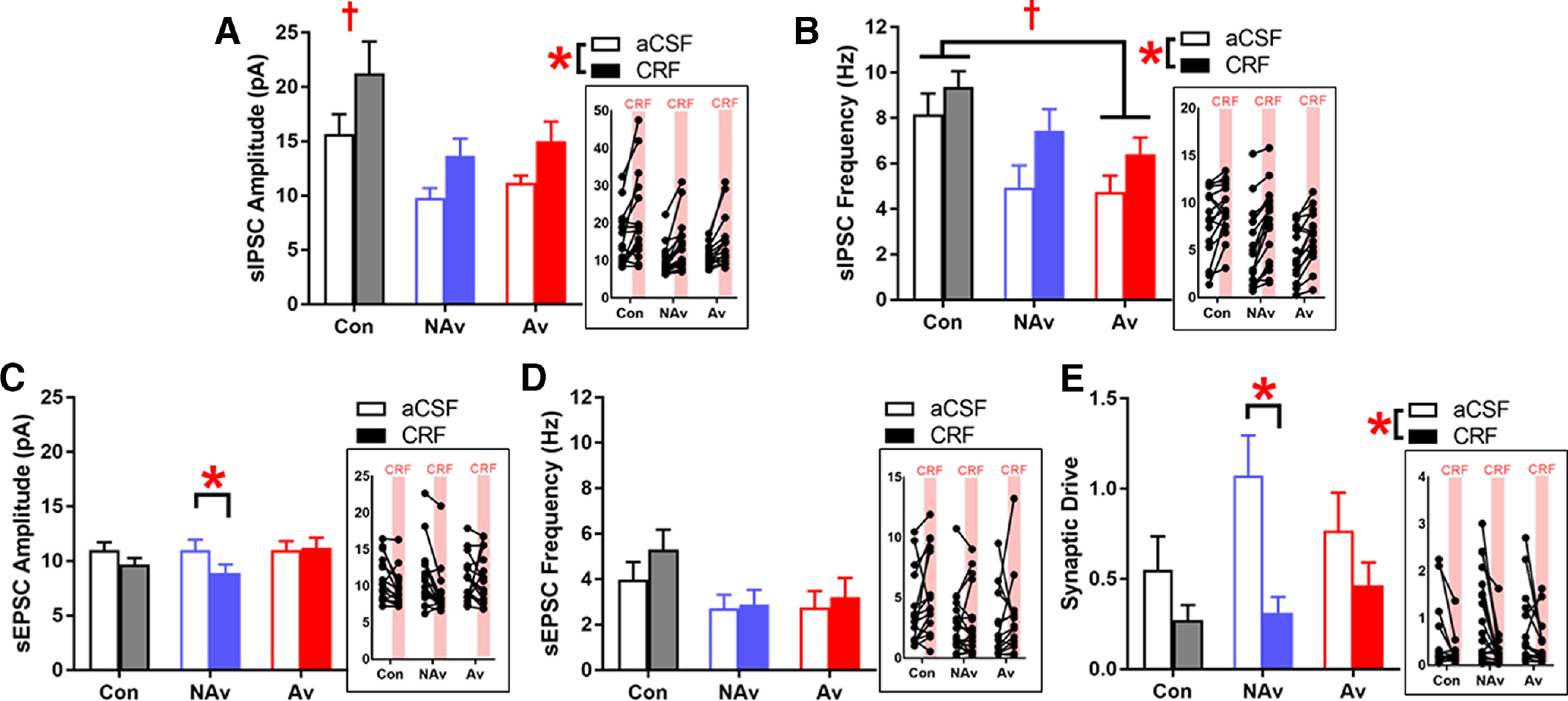

Experiment 5: CRF increases synaptic inhibition in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from stressed and unstressed rats, but attenuates synaptic drive in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Non-Avoiders only

Immediately following Experiment 3, we tested the effects of bath application of the stress neuropeptide, CRF, on spontaneous synaptic transmission in a subset of CRF1 CeA-LH cells. We found that CRF increased sIPSC amplitudes in CRF1 CeA-LH cells in Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls [Fig. 5A; repeated-measures ANOVA (CRF × stress group), main effect of CRF (F(1,46) = 33.5, p < 0.001)]. As reported in Experiment 3, regardless of CRF treatment, CRF1 CeA-LH cells from both Avoiders and Non-Avoiders have lower sIPSC amplitudes compared with unstressed Controls [Fig. 5A; main effect of stress group (F(2,46) = 4.8, p = 0.012); Tukey's post hoc: Controls > Avoiders (p = 0.059), Controls > Non-Avoiders (p = 0.012)]. CRF also increased sIPSC frequencies in CRF1 CeA-LH across all stress groups [Fig. 5B; repeated-measures ANOVA (CRF × stress group), main effect of CRF (F(1,46) = 51.4, p < 0.001)]. In addition, we saw that CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoiders had lower sIPSC frequencies compared with Controls, regardless of CRF treatment [Fig. 5B; repeated-measures ANOVA, main effect of stress group (F(2,46) = 4.1, p = 0.024); Tukey's post hoc: Controls > Avoiders (p = 0.029), Controls vs Non-Avoiders not significant].

Figure 5.

CRF attenuates synaptic drive in CRF1 CeA-LH cells in Non-Avoiders only. A, sIPSC amplitude. B, sIPSC frequency. C, sEPSC amplitude. D, sEPSC frequency. E, Synaptic drive. *Significant difference between aCSF and CRF conditions. †Significant difference between stress groups. Insets, Data points from individual cells. Data are shown collapsed by sex (males: Controls, n = 11 cells; Non-Avoiders, n = 7 cells; Avoiders, n = 9 cells; females: Controls, n = 5 cells; Non-Avoiders, n = 11 cells; Avoiders, n = 6 cells).

With regards to excitatory synaptic transmission, CRF produced a small decrease in sEPSC amplitudes in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Non-Avoiders only [Fig. 5C; repeated-measures ANOVA, CRF × stress group interaction (p = 0.068), main effect of CRF in Non-Avoiders only (F(1,17) = 12.1, p = 0.003)]. CRF had no effect on sEPSC frequencies (Fig. 5D). We then calculated a synaptic drive index [(sEPSC amplitude × frequency)/(sIPSC amplitude × frequency)] for all recorded CRF1 CeA-LH cells and found that CRF attenuated synaptic drives across all groups [Fig. 5E; main effect of CRF (F(1,46) = 18.1, p < 0.001)], and that this effect was largest in Non-Avoiders [CRF × stress group interaction (p = 0.102), main effect of CRF in Non-Avoiders only following within-group analyses (F(1,17) = 13.9, p = 0.002)].

Discussion

Collectively, our results show that LH-projecting CeA cells that express CRF1 receptors are important for supporting increases in anxiety-like behavior and alcohol self-administration in male and female rats after exposure to bobcat urine odor. We found that predator odor exposure induced expression of the immediate early gene, c-Fos, in CRF1 CeA-LH cells in Avoider but not Non-Avoider rats. Given that Avoider rats show persistent avoidance of stress-paired contexts and long-lasting increases in alcohol drinking after stress, we predicted that CRF1 CeA-LH cell activity following stress exposure is important for supporting these post-stress behavioral phenomena. Importantly, there were no differences in the total number of CeA CRF1-expressing cells, LH-projecting CeA cells, or CRF1-expressing LH-projecting CeA cells, as measured by tdTomato labeling, cholera toxin B labeling, or tdTomato and cholera toxin B colabeling, respectively, between Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and unstressed Controls. This suggests that Avoider versus Non-Avoider behavioral differences are not attributable to differences in the density of these CeA cell populations.

Using DREADDs, we tested the effect of CRF1 CeA-LH cell inhibition on post-stress escalation of alcohol self-administration and avoidance behavior. We found that chemogenetic inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells via hM4D(Gi) receptors during post-stress alcohol self-administration test sessions normalized the escalated alcohol responding in Avoider rats, suggesting that increased activity of these cells is important for promoting operant responding for alcohol after stress. However, we found that chemogenetic inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells had no effect on avoidance of stress-paired contexts. Finally, we report that Avoider rats (injected with EGFP control virus) showed higher anxiety-like behavior than Non-Avoiders and unstressed Controls 9 d after predator odor exposure. Our laboratory previously re ported that predator odor stress increases anxiety-like behavior in stressed rats (vs unstressed Controls) when tested at 2 d (using the EPM test) and 5 d (using the open field test) post-stress, with no differences between Avoiders and Non-Avoiders (Whitaker and Gilpin, 2015). Our current finding that Avoiders exhibit greater anxiety-like behavior compared with Non-Avoiders and unstressed Controls 9 d after stress exposure suggests that stress-induced anxiogenesis has resolved by this time point in Non-Avoiders but persists in Avoider rats. That said, it is important to note that the rats tested by Whitaker and Gilpin (2015) were never exposed to alcohol, and were all male Wistars, whereas the rats tested here had a history of alcohol drinking, and were a combination of male and female CRF1-Cre rats (on a Wistar background). Other work from our group reported that post-stress increases in anxiety-like behavior in male and female Avoider rats resolve by post-stress day 17 (Albrechet-Souza and Gilpin, 2019).

In rats expressing the hM4D(Gi) receptor in CRF1 CeA-LH cells, chemogenetic inhibition of these cells normalized anxiety-like behavior in Avoider rats, suggesting that increased activity in CRF1 CeA-LH cells not only supports more alcohol drinking but also heightened anxiety-like behavior after stress. Given that anxiety and alcohol drinking are closely linked in humans, we performed a correlational analysis between time in open arms of the EPM and operant alcohol responding in stressed rats. We found that higher anxiety-like behavior is associated with higher operant alcohol responding in stressed rats. We also report that higher avoidance scores predict higher anxiety-like behavior in the EPM and higher levels of operant alcohol responding, suggesting a tripartite relationship between avoidance, anxiety-like behavior, and alcohol responding. Here, inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells did not alter avoidance of stress-paired contexts, whereas our prior work showed that inhibition of all LH-projecting CeA cells attenuates avoidance of stress-paired contexts (Weera et al., 2021), suggesting that avoidance behavior is mediated/encoded by LH-projecting CeA cells that do not necessarily express CRF1.

We previously demonstrated that avoidance of predator odor-paired contexts and escalated alcohol self-administration in Avoiders persist for weeks after bobcat urine exposure (e.g., Edwards et al., 2013; Weera et al., 2020). Here, our DREADD experiments show that chemogenetic inhibition of CRF1 CeA-LH cells immediately before behavioral testing acutely reduces alcohol self-administration and anxiety-like behavior in Avoider rats. Prior work from our group showed that male Avoider rats exhibit increases in CRF peptide content in the CeA (as measured by radioimmunoassay) 12 d after bobcat urine exposure (Itoga et al., 2016), and that acute pretest CRF1 receptor antagonism in CeA reduces alcohol self-administration and avoidance behavior in male Avoider rats at protracted time points following bobcat urine exposure (Weera et al., 2020). It is currently unclear how long-lasting bobcat urine exposure effects are on CRF peptide content/signaling and the activity of CRF-positive and CRF1 receptor-positive cells in CeA, and it is likewise unclear whether there are any long-lasting effects of CRF1 receptor antagonism or CRF1-positive cell inhibition on post-stress avoidance and alcohol drinking. Future studies should explore these questions.

To identify potential mechanisms whereby stress alters the activity of CRF1 CeA-LH cells, we performed ex vivo slice electrophysiology to record synaptic transmission and intrinsic properties in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from stressed (Avoiders and Non-Avoiders) and unstressed rats. We found that stress exposure reduces the amplitude of spontaneous inhibitory currents in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from both Avoiders and Non-Avoiders, suggesting that stress produces neuroadaptations at the postsynaptic terminal that renders these cells less sensitive to synaptic inhibition (e.g., decreased expression of GABAA receptors and/or changes in expression pattern of GABAA receptor subtypes). We also calculated a synaptic drive ratio based on sIPSC and sEPSC frequency and amplitude values for each cell (see Materials and Methods) (e.g., Levine et al., 2021), and found that CRF1 CeA-LH cells from stressed rats have elevated synaptic drive compared with cells from unstressed rats. Given that sIPSC frequencies, sEPSC amplitudes, and sEPSC frequencies were not different between these groups of rats, we surmise that the elevated synaptic drive in stressed rats is driven by smaller sIPSC amplitudes in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from these rats. Overall, these findings suggest that CRF1 CeA-LH cells in stressed rats are more excited than cells in unstressed Controls, an effect that is reminiscent of prior results in mice showing that chronic alcohol exposure reduces tonic inhibition of CeA CRF1 cells (Herman et al., 2016).

Given that CRF-CRF1 signaling in the CeA promotes an Avoider-like phenotype, we tested the effects of in vitro CRF application on synaptic transmission in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoider, Non-Avoider, and unstressed Control rats. In general, CRF facilitates inhibitory synaptic transmission in CeA cells via activation of presynaptic CRF1 on GABAergic terminals (Nie et al., 2004; Roberto et al., 2010). At the same time, CRF may either promote or inhibit excitatory transmission in CeA cells via CRF1-dependent mechanisms, depending on the activity state of synaptic inputs (Varodayan et al., 2017). Therefore, CRF may produce either a net decrease or increase in synaptic drive. As discussed above, in vivo studies show that increases in CRF signaling via CRF1 receptors and also activation of CRF1 CeA-LH cells are important for supporting an Avoider phenotype. Therefore, in ex vivo CeA slices, we hypothesized that CRF would increase the synaptic drive in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoider rats (mimicking the effect of stress), thereby facilitating activation of these cells in vivo during stressful events. In contrast to this prediction, we found that CRF decreases synaptic drive in CRF1 CeA-LH cells from Avoiders, Non-Avoiders, and Controls, via facilitation of inhibitory transmission in these cells. Considering that stress reduces inhibitory transmission and increases synaptic drive in CRF1 CeA-LH cells, CRF-induced facilitation of inhibitory transmission essentially counters the effects of stress. An important consideration that may help reconcile in vivo and ex vivo results is the time points at which testing occurs. In vivo studies typically occur days after stress, whereas slice electrophysiology experiments occur hours after stress. It is possible that the synaptic inhibition produced by CRF during or shortly after stress exposure is important for preventing an upregulation of synaptic excitability at protracted time points. In support of this idea, CRF-induced blunting of synaptic drive is more robust in Non-Avoiders than in Avoiders. We speculate that this is a mechanism that protects against hyperexcitation of CRF1 CeA-LH cells, thereby conferring resilience against increased anxiety-like behavior and alcohol drinking at protracted time points, and we will test this hypothesis in future work. Collectively, these results show that recruitment of LH-projecting CeA cells that express CRF1 receptors are important for supporting post-stress increases in anxiety-like behavior and alcohol self-administration in male and female rats.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AA029726 and AA027145 to M.M.W., and Grants AA023305, AA026531, AA025792, and AA028727 to N.W.G.; and in part by Department of Veterans Affairs, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service Merit Review Award BX003451 to N.W.G.

N.W.G. owns shares in Glauser Life Sciences, Inc., a company with interest in developing therapeutics for mental health disorders. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Albrechet-Souza L, Gilpin NW (2019) The predator odor avoidance model of post-traumatic stress disorder in rats. Behav Pharmacol 30:105–114. 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaudova I, Kindt M, Fanselow M, Beckers T (2017) Pathways towards the proliferation of avoidance in anxiety and implications for treatment. Behav Res Ther 96:3–13. 10.1016/j.brat.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avegno EM, Lobell TD, Itoga CA, Baynes BB, Whitaker AM, Weera MM, Edwards S, Middleton JW, Gilpin NW (2018) Central amygdala circuits mediate hyperalgesia in alcohol-dependent rats. J Neurosci 38:7761–7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura J, et al. (2019) High-potency ligands for DREADD imaging and activation in rodents and monkeys. Nat Commun 10:4627. 10.1038/s41467-019-12236-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Harvey AG (1995) Processing threatening information in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 104:537–541. 10.1037//0021-843x.104.3.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembrow NC, Chitwood RA, Johnston D (2010) Projection-specific neuromodulation of medial prefrontal cortex neurons. J Neurosci 30:16922–16937. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3644-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Baynes BB, Carmichael CY, Zamora-Martinez ER, Barrus M, Koob GF, Gilpin NW (2013) Traumatic stress reactivity promotes excessive alcohol drinking and alters the balance of prefrontal cortex-amygdala activity. Transl Psychiatry 3:e296. 10.1038/tp.2013.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman MA, Contet C, Roberto M (2016) A functional switch in tonic GABA currents alters the output of central amygdala corticotropin releasing factor receptor-1 neurons following chronic ethanol exposure. J Neurosci 36:10729–10741. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1267-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Brennan PL, Schutte KK (2005) Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. J Consult Clin Psychol 73:658–666. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska B, Pacella-LaBarbara M, George RL, Delahanty DL (2023) Avoidance coping as a vulnerability factor for negative drinking consequences among injury survivors experiencing PTSD symptoms: an ecological momentary assessment study. J Psychoactive Drugs. Advance online publication. Retrieved Apr 9, 2023. 10.1080/02791072.2023.2200780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoga CA, Roltsch-Hellard EA, Whitaker AM, Lu YL, Schreiber AL, Baynes BB, Baiamonte BA, Richardson HN, Gilpin NW (2016) Traumatic stress promotes hyperalgesia via corticotropin-releasing factor-1 receptor (CRFR1) signaling in central amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:2463–2472. 10.1038/npp.2016.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Middleton JW, Anderson CT, Borges K, Suter BA, Shepherd GM, Tzounopoulos T (2015) Cell-specific activity-dependent fractionation of layer 2/3→5B excitatory signaling in mouse auditory cortex. J Neurosci 35:3112–3123. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0836-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DP, Albrechet-Souza L, Cruise S, Maiya R, Destouni A, Sakamuri SV, Duplooy A, Hibicke M, Nichols C, Katakam PV, Gilpin NW, Francis J (2023) Conditioned place avoidance is associated with a distinct hippocampal phenotype, partly preserved pattern separation, and reduced reactive oxygen species production after stress. Genes Brain Behav 22:e12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettek JE, Price JL (1978) Amygdaloid projections to subcortical structures within the basal forebrain and brainstem in the rat and cat. J Comp Neurol 178:225–254. 10.1002/cne.901780204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine OB, Skelly MJ, Miller JD, Rivera-Irizarry JK, Rowson SA, DiBerto JF, Rinker JA, Thiele TE, Kash TL, Pleil KE (2021) The paraventricular thalamus provides a polysynaptic brake on limbic CRF neurons to sex-dependently blunt binge alcohol drinking and avoidance behavior in mice. Nat Commun 12:5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux J, Katz P, Edwards S, Middleton JW, Molina PE (2017) Inhibition of endocannabinoid degradation improves outcomes from mild traumatic brain injury: a mechanistic role for synaptic hyperexcitability. J Neurotrauma 34:436–443. 10.1089/neu.2016.4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z, Schweitzer P, Roberts AJ, Madamba SG, Moore SD, Siggins GR (2004) Ethanol augments GABAergic transmission in the central amygdala via CRF1 receptors. Science 303:1512–1514. 10.1126/science.1092550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto M, et al. (2010) Corticotropin releasing factor-induced amygdala GABA release plays a key role in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry 67:831–839. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber AL, Lu YL, Baynes BB, Richardson HN, Gilpin NW (2017) Corticotropin-releasing factor in ventromedial prefrontal cortex mediates avoidance of a traumatic stress-paired context. Neuropharmacology 113:323–330. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Petrovich GD (1998) What is the amygdala? Trends Neurosci 21:323–331. 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01265-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varodayan FP, Correia D, Kirson D, Khom S, Oleata CS, Luu G, Schweitzer P, Roberto M (2017) CRF modulates glutamate transmission in the central amygdala of naïve and ethanol-dependent rats. Neuropharmacology 125:418–428. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura-Silva AP, Melo A, Ferreira AC, Carvalho MM, Campos FL, Sousa N, Pêgo JM (2013) Excitotoxic lesions in the central nucleus of the amygdala attenuate stress-induced anxiety behavior. Front Behav Neurosci 7:32. 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weera MM, Schreiber AL, Avegno EM, Gilpin NW (2020) The role of central amygdala corticotropin-releasing factor in predator odor stress-induced avoidance behavior and escalated alcohol drinking in rats. Neuropharmacology 166:107979. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.107979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weera MM, Shackett RS, Kramer HM, Middleton JW, Gilpin NW (2021) Central amygdala projections to lateral hypothalamus mediate avoidance behavior in rats. J Neurosci 41:61–72. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0236-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weera MM, Agoglia AE, Douglass E, Jiang Z, Rajamanickam S, Shackett RS, Herman MA, Justice NJ, Gilpin NW (2022) Generation of a CRF1-Cre transgenic rats and the role of central amygdala CRF1 cells in nociception and anxiety-like behavior. Elife 11:e67822. 10.7554/eLife.67822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker AM, Gilpin NW (2015) Blunted hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis response to predator odor predicts high stress reactivity. Physiol Behav 147:16–22. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]