Abstract

Background and Objectives

There are limited validated biomarkers in Parkinson disease (PD) which substantially hinders the ability to monitor disease progression and consequently measure the efficacy of disease-modifying treatments. Imaging biomarkers, such as vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) PET, enable enhanced diagnostic accuracy and detect early neurodegenerative changes associated with prodromal PD. This study sought to assess whether 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET is sensitive enough to monitor and quantify disease progression over a 2-year window.

Methods

18F-AV-133 PET scans were performed on participants with PD and REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) and neurologic controls (NC). All participants were scanned twice ∼26 months apart. Regional tracer retention was calculated with a primary visual cortex reference region and expressed as the standard uptake volume ratio. Regions of interest included caudate, anterior, and posterior putamen. At the time of scanning, participants underwent clinical evaluation including UPDRSMOTOR test, Sniffin’ Sticks, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score.

Results

Over the 26-month interval, a significant decline in PET signal was observed in all 3 regions in participants with PD (N = 26) compared with NC (N = 12), consistent with a decrease in VMAT2 level and ongoing neurodegeneration. Imaging trajectory calculations suggest that the neurodegeneration in PD occurs over ∼33 years [CI: 27.2–39.5], with ∼10.5 years [CI: 9.1–11.3] of degeneration in the posterior putamen before it becomes detectable on a VMAT2 PET scan, a further ∼6.5 years [CI: 1.6–12.7] until symptom onset, and a further ∼3 years [CI: 0.3–8.7] until clinical diagnosis.

Discussion

Over a 2-year period, 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET was able to detect progression of nigrostriatal degeneration in participants with PD, and it represents a sensitive tool to identify individuals at risk of progression to PD, which are currently lacking using clinical readouts. Trajectory models propose that there is nigrostriatal degeneration occurring for 20 years before clinical diagnosis. These data demonstrate that VMAT2 PET provides a sensitive measure to monitor neurodegenerative progression of PD which has implications for PD diagnostics and subsequently clinical trial patient stratification and monitoring.

Classification of Evidence

This study provides Class IV evidence that VMAT2 PET can detect patients with Parkinson disease and quantify progression over a 2-year window.

Introduction

Diagnosis of Parkinson disease (PD) remains challenging and relies on the presentation of overt motor impairment which occurs in the latter stages of the neurodegenerative cascade. Approximately 50%–70% of dopaminergic terminals in the putamen have perished before the presentation of unilateral motor symptoms and subsequent clinical diagnosis.1,2 This late identification of disease is further complicated by the reliance on subjective movement assessments for clinical diagnosis.3 In a primary care setting, only 58% of patients in the early stages of clinical disease (<5 years since onset of motor symptoms) are accurately diagnosed,4 highlighting the shortcomings of the current diagnostic approach. This is due, in part, to a lack of suitable biomarkers to support clinical evaluations. A valid diagnosis in the earliest stages of disease is crucial to disease management to advance our understanding of clinicopathologic relationships, specifically in the preclinical and prodromal phases, and to facilitate appropriate clinical trial recruitment.

Reliable neuroimaging biomarkers provide enhanced clinical diagnostic accuracy in PD.5 Previously, we have established that 18F-AV-133 vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) PET brain imaging is a useful tool in improving diagnostic accuracy in patients with clinically uncertain parkinsonian syndrome (CUPS), altering diagnosis in 23%, changing management in 53%, and improving overall diagnostic confidence in 75% of cases.6 Furthermore, the diagnostic accuracy remains robust even after 3 years, with follow-up diagnosis remaining concordant with the 18F-AV-133 PET scan result in 94% of cases.7

Without validated staging and prognostic biomarkers, the ability to monitor disease progression, and, therefore, determine the efficacy of disease-modifying therapies, is substantially impaired. The progression of nigrostriatal degeneration in PD has been previously evaluated using 123I-β-CIT single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and 18F-DOPA PET.8-10 The results have varied based on region of interest and the imaging modality and analysis. Extrapolated rates of decline have been used to estimate the preclinical period in PD, with results varying from 2.8 to 37.2 years depending on the individual study parameters.8-10 Importantly, these calculations assumed linear rates of degeneration; however, the speed of decline is significantly greater in patients with PD11,12 and is most prominent in early clinical disease.8,13,14 In addition, these studies lacked regional specificity in that they examined the entire striatum (putamen, caudate, and nucleus accumbens) or the whole putamen. It is now understood that there is a topographical loss of synapses in PD, starting in the posterior putamen, followed by the anterior putamen and the caudate.15

A robust estimate of the neurodegenerative course in PD is complex and requires the consideration of several factors. First, the rate of decline may be different between brain regions. Second, the progression of neurodegeneration is not linear, and modeling of data must account for shifting rates of decline. Third, assessing the integrity of the nigrostriatal pathway may be confounded by compensatory terminal sprouting aimed at maintaining intrasynaptic dopaminergic tone.16,17 Finally, given the extensive synaptic loss that has occurred by the time of clinical diagnosis, representation of the prodromal phase with a cohort of participants at greater risk of developing PD, such as those with REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), will provide insight into the early stages of neurodegeneration. We have previously demonstrated that 18F-AV-133 is capable of detecting the early degeneration in people with probable prodromal PD (concurrent RBD, anxiety, and hyposmia).18

Despite advances in PET tracers increasing diagnostic capabilities, it is unknown whether PET signal changes significantly in a short timeframe and can track the neurodegenerative cascade more accurately than existing biomarkers in PD. This study aims to evaluate the regional dopaminergic degeneration in PD and RBD over time and investigate whether 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET is sensitive enough to monitor and quantify disease progression in a 2-year window.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the private and public clinics of movement disorders and respiratory physicians from Melbourne, Australia. All patients previously recruited in our CUPS study were eligible for this study.6 The diagnosis of CUPS was made by the referring clinician and included features of atypical clinical features of parkinsonism, poor levodopa responsiveness, absence of disease progression, young age of onset, or presence of dystonia. The diagnosis of RBD was made by a clinician with the assistance of the MAYO sleep questionnaire (informant). For the purposes of this study, we are reporting the findings from participants with CUPS with a final diagnosis of PD, as well as RBD and neurologic controls (NC). Some of these data were previously reported.6,7

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All procedures were approved by the Austin Health Research Ethics Committee (H2010/03952), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Study Design

All participants had an 18F-AV-133 PET scan and clinical assessment at the time of recruitment, and a second scan and assessment were obtained 19–42 months later (26.3 ± 4.4 (SD)). The final diagnosis was made by the treating neurologist, who had access to the results of the first scan.

Clinical Assessment

Clinical assessment included the motor subscale (Section III) of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRSMOTOR) off medication (medication stopped 24 hours before the examination and resumed just before the PET scan), Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) score, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADSANX and HADSDEP), and olfactory analysis using the Sniffin’ Sticks (Medisense, the Netherlands).

PET Scan Protocol and Image Analysis

As outlined in our previous works, a 20-minute emission PET scan was obtained 2 hours after an intravenous injection of 250 MBq of 18F-AV-133 on a Philips Allegro System.7 PET scans were attenuation corrected using a transmission scan and reconstructed using 3D row action maximum likelihood algorithm. All scans were spatially normalized to a normal 18F-AV-133 template in the MNI space using an in-house MR-Less software based on SPM8.19 The primary visual cortex, a region largely devoid of monoaminergic terminals, was used as a reference region. The region tracer retention was extracted using a standard region of interest (ROI) template which was previously constructed manually over 13 slices for the caudate and 8 slices for the putamen (each slice 2 mm thick). The putamen ROI was bisected to yield anterior and posterior putamen binding. The regional tracer retention in the caudate, anterior, and posterior putamen was calculated by generating the ratio of the targets regions to the reference region and expressed as a standard uptake value ratio (SUVR).

Progression Calculations

The annual change in 18F-AV-133 uptake in each region was calculated by the SUVR change over time. The natural history of progressive nigrostriatal terminal degeneration in PD, as assessed by 18F-AV-133, was evaluated using the four-step procedure described previously20 using only the NC and the participants with PD. In each ROI separately, this procedure estimates the mean and slope of each pair (baseline and follow-up) of 18F-AV-133 SUVR for each hemisphere, fits a polynomial to the estimated means and slopes across all individuals, integrates a second-order polynomial fits over time, and inverts this relationship to get the single variable mean trajectory curves as a function of disease time. More generally this procedure is a description of the resolution of an ordinary differential equation, where F is the fitted second-order polynomial:

|

To compare the regional trajectory curves and consider difference in normal regional tracer uptake, all SUVR values were normalized for each ROI independently between 0 and 1, with 1 representing normal retention and 0 the worst measured retention. A bootstrapping protocol was used providing confidence limits on the curves and on disease time predictions.

Sample Size Calculations

Sample size estimates were performed to calculate expected sample sizes for prospective studies using the annual percentage rate of change data reported in this study assuming that a neuroprotective agent will slow the rate of decline by either 50% or 20%.

Statistical Analysis

Sex data were analyzed using the χ2 test. Normality was tested on all continuous data using the Shapiro-Wilk test (eTable 1, links.lww.com/WNL/D167). Nonnormal data were compared by a Kruskal-Wallis test with the Dunn multiple comparison test (test factors are reported in eTable 2). 18F-AV-133 SUVR was calculated for left and right hemisphere ROIs, thus for statistical analysis involving SUVR, a linear mixed model with participant ID as a random variable was used to account for the inclusion of quantification from both hemispheres. Data processing and statistical analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2016 software, Graphpad Prism 9.2.0 (2020), and R V.3.4.3.1923.

Data Availability

Deidentified data used for this study are available on request by qualified investigators.

Results

Participants

This study included 26 participants with PD, 11 participants with RBD, and 12 NC. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of participants. The PD group were significantly younger than NC (56.9 ± 11.8 vs 71.3 ± 4.8, p = 0.001) and RBD groups (56.9 ± 11.8 vs 68.0 ± 12.6, p = 0.03). There were significantly more male participants in the study (NC - N = 7 (58%), RBD - 11 (100%), PD - 12 (46%); χ2 (2, N = 49) = 9.5, p = 0.009). There were no significant differences in the scan interval between any of the groups.

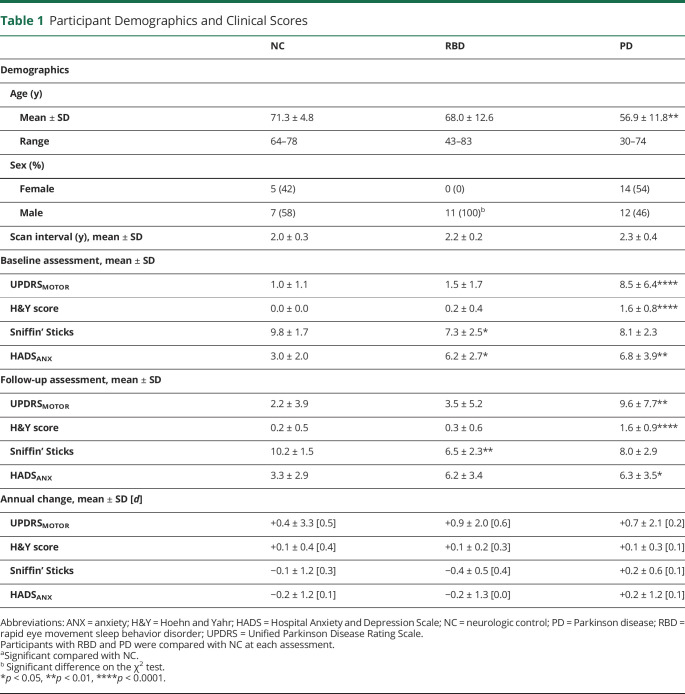

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Clinical Scores

| NC | RBD | PD | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (y) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 71.3 ± 4.8 | 68.0 ± 12.6 | 56.9 ± 11.8** |

| Range | 64–78 | 43–83 | 30–74 |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Female | 5 (42) | 0 (0) | 14 (54) |

| Male | 7 (58) | 11 (100)b | 12 (46) |

| Scan interval (y), mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.4 |

| Baseline assessment, mean ± SD | |||

| UPDRSMOTOR | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 8.5 ± 6.4**** |

| H&Y score | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.8**** |

| Sniffin’ Sticks | 9.8 ± 1.7 | 7.3 ± 2.5* | 8.1 ± 2.3 |

| HADSANX | 3.0 ± 2.0 | 6.2 ± 2.7* | 6.8 ± 3.9** |

| Follow-up assessment, mean ± SD | |||

| UPDRSMOTOR | 2.2 ± 3.9 | 3.5 ± 5.2 | 9.6 ± 7.7** |

| H&Y score | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.9**** |

| Sniffin’ Sticks | 10.2 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 2.3** | 8.0 ± 2.9 |

| HADSANX | 3.3 ± 2.9 | 6.2 ± 3.4 | 6.3 ± 3.5* |

| Annual change, mean ± SD [d] | |||

| UPDRSMOTOR | +0.4 ± 3.3 [0.5] | +0.9 ± 2.0 [0.6] | +0.7 ± 2.1 [0.2] |

| H&Y score | +0.1 ± 0.4 [0.4] | +0.1 ± 0.2 [0.3] | +0.1 ± 0.3 [0.1] |

| Sniffin’ Sticks | −0.1 ± 1.2 [0.3] | −0.4 ± 0.5 [0.4] | +0.2 ± 0.6 [0.1] |

| HADSANX | −0.2 ± 1.2 [0.1] | −0.2 ± 1.3 [0.0] | +0.2 ± 1.2 [0.1] |

Abbreviations: ANX = anxiety; H&Y = Hoehn and Yahr; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NC = neurologic control; PD = Parkinson disease; RBD = rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale.

Participants with RBD and PD were compared with NC at each assessment.

aSignificant compared with NC.

Significant difference on the χ2 test.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Clinical Assessment

Comparisons were made between each subpopulation of PD and RBD to normal controls at each time point (Table 1). Participants with PD had a significantly higher UPDRSMOTOR score at both assessments compared with NC (baseline: 8.5 ± 6.4 vs 1.01 ± 1.1, p < 0.0001; follow-up: 9.6 ± 7.7 vs 2.2 ± 3.9, p = 0.001) and RBD (baseline: 8.5 ± 6.4 vs 1.5 ± 1.7, p < 0.0001; follow-up 9.6 ± 7.7 vs 3.5 ± 5.2, p = 0.01). Similarly, participants with PD had a significantly higher H&Y score across both assessments compared with NC (baseline: 1.6 ± 0.8 vs 0.0 ± 0.0, p < 0.0001; follow-up: 1.6 ± 0.9 vs 0.2 ± 0.5, p < 0.0001) and RBD (baseline: 1.6 ± 0.8 vs 0.2 ± 0.4, p < 0.0001; follow-up: 1.6 ± 0.9 vs 0.3 ± 0.6, p = 0.0004). At both assessments, participants with RBD had a significantly lower olfactory score on the Sniffin’ Sticks compared with NC (baseline: 7.3 ± 2.5 vs 9.8 ± 1.7, p = 0.03; follow-up: 6.5 ± 2.3 vs 10.2 ± 1.5, p = 0.002). Participants with PD had nonstatistically significant lower olfactory scores both in baseline and follow-up compared with NC and RBD subpopulations (Table 1). At baseline, participants with RBD and PD had significantly higher anxiety scores (HADSANX) (RBD: 6.2 ± 2.7 vs 3.0 ± 2.0, p = 0.046; PD: 6.8 ± 3.9 vs 3.0 ± 2.0, p = 0.005). At the follow-up assessment, there was a significant difference in the anxiety score in the participants with PD (6.3 ± 3.5 vs 3.3 ± 2.9, p = 0.03) There were no differences in HADSDEP between any of the groups. There were no significant differences in clinical assessments between baseline and follow-up assessment within any group.

Regional SUVR Decline in REM Sleep Behavior Disorder and Parkinson Disease

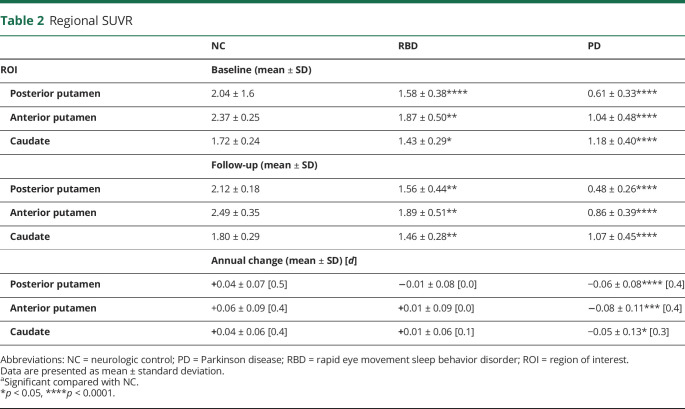

SUVR was calculated for the posterior putamen, anterior putamen, and caudate at baseline and at follow-up. Descriptive statistics of SUVR at baseline and follow-up and annual change are presented in Table 2, and data are presented in Figure 1. One RBD and 2 participants with PD were excluded because of technical issues associated with PET scans (one participant had unusually large ventricles which affected quantification in the reference region and 2 were unable to be normalized because of poor scan quality).

Table 2.

Regional SUVR

| NC | RBD | PD | |

| ROI | Baseline (mean ± SD) | ||

| Posterior putamen | 2.04 ± 1.6 | 1.58 ± 0.38**** | 0.61 ± 0.33**** |

| Anterior putamen | 2.37 ± 0.25 | 1.87 ± 0.50** | 1.04 ± 0.48**** |

| Caudate | 1.72 ± 0.24 | 1.43 ± 0.29* | 1.18 ± 0.40**** |

| Follow-up (mean ± SD) | |||

| Posterior putamen | 2.12 ± 0.18 | 1.56 ± 0.44** | 0.48 ± 0.26**** |

| Anterior putamen | 2.49 ± 0.35 | 1.89 ± 0.51** | 0.86 ± 0.39**** |

| Caudate | 1.80 ± 0.29 | 1.46 ± 0.28** | 1.07 ± 0.45**** |

| Annual change (mean ± SD) [d] | |||

| Posterior putamen | +0.04 ± 0.07 [0.5] | −0.01 ± 0.08 [0.0] | −0.06 ± 0.08**** [0.4] |

| Anterior putamen | +0.06 ± 0.09 [0.4] | +0.01 ± 0.09 [0.0] | −0.08 ± 0.11*** [0.4] |

| Caudate | +0.04 ± 0.06 [0.4] | +0.01 ± 0.06 [0.1] | −0.05 ± 0.13* [0.3] |

Abbreviations: NC = neurologic control; PD = Parkinson disease; RBD = rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder; ROI = region of interest.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

aSignificant compared with NC.

*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

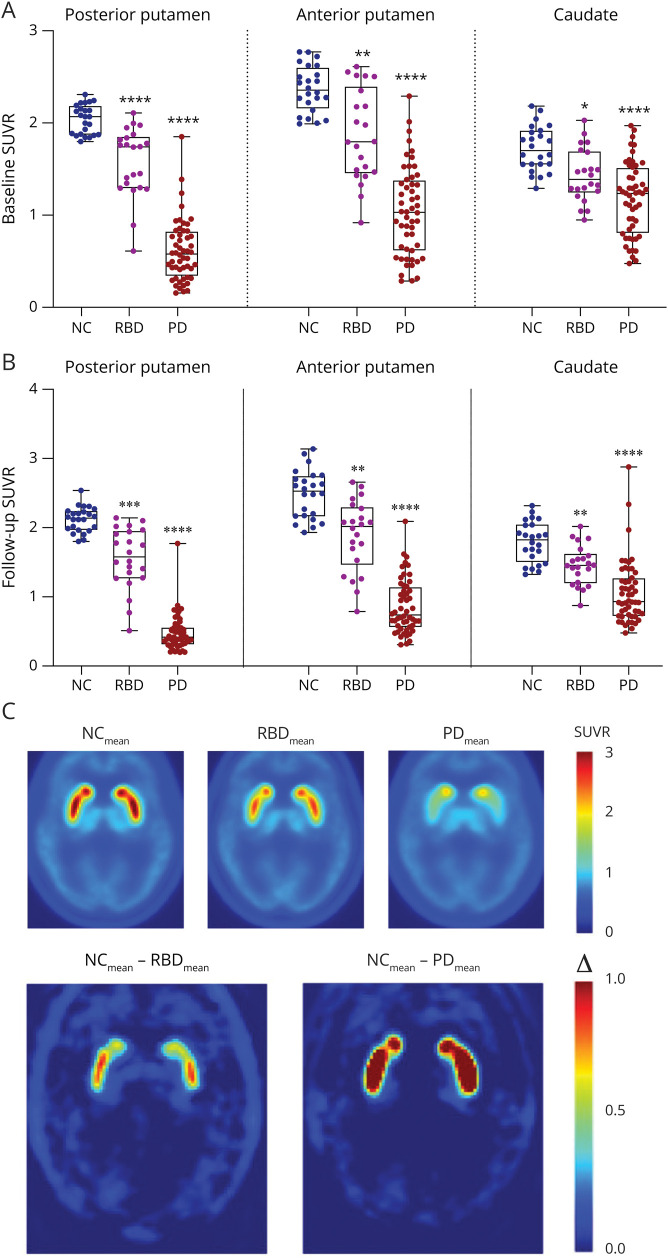

Figure 1. VMAT2 18F-AV-133 SUVR in the REM Sleep Behavior Disorder and Parkinson Disease Brain.

(A) Baseline posterior and anterior putamen and caudate SUVR levels and (B) follow-up posterior and anterior putamen and caudate SUVR levels. (C) Average VMAT2 scans for the neurologic control (NC), REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and Parkinson disease (PD) groups. The bottom row displays the difference in means of the NC and RBD and of NC and PD. Boxplot horizontal lines represent the median and whiskers reflect minimum and maximum values. Δ: difference in means, SUVR = standardized uptake value ratio. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 ****p < 0.0001.

At baseline, there was a significantly lower SUVR in the RBD group compared with NC in the posterior putamen (1.58 ± 0.38 vs 2.04 ± 0.16, p < 0.0001), anterior putamen (1.87 ± 0.50 vs 2.37 ± 0.25, p = 0.004), and caudate (1.43 ± 0.29 vs 1.72 ± 0.24, p = 0.01). At baseline, there was a significantly lower SUVR in the PD group compared with NC in the posterior putamen (0.61 ± 0.33 vs 2.04 ± 0.16, p < 0.0001), anterior putamen (1.04 ± 0.48 vs 2.37 ± 0.25, p < 0.0001), and caudate (1.18 ± 0.40 vs 1.72 ± 0.24, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1A). At follow-up, there was a significantly lower SUVR in the 3 investigated regions of the RBD group compared with NC (posterior putamen: 1.56 ± 0.44 vs 2.12 ± 0.18, p = 0.0001; anterior putamen: 1.89 ± 0.51 vs 2.49 ± 0.35, p = 0.002; caudate: 1.46 ± 0.28 vs 1.80 ± 0.29, p = 0.009). The PD group had significantly lower SUVR in all 3 regions compared with NC (posterior putamen: 0.48 ± 0.26 vs 2.12 ± 0.18, p < 0.0001; anterior putamen: 0.86 ± 0.39 vs 2.49 ± 0.35, p < 0.0001; caudate: 1.07 ± 0.45 vs 1.80 ± 0.29, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1B). Average VMAT2 scans for the NC, RBD, and PD and the difference between the means of the NC and RBD and of the NC and PD are presented in Figure 1C. Group comparisons indicated no significant hemispherical asymmetry in the RBD compared with NC (p ∼ 0.5), but a higher posterior putamen over caudate ratio was observed in individuals with RBD when compared with NC (p = 0.01).

Normality of RBD SUVR scores was calculated, and abnormality was defined by a Z score of ±2.5. At baseline, the Z score was abnormal in the posterior putamen (−3.0 ± 2.4) compared with NC and was low but not abnormal in the anterior putamen (−2.0 ± 2.0) and caudate (−1.2 ± 1.2). These changes were consistent at follow-up, with abnormality in the posterior putamen (Z = −3.1 ± 2.5) but not in the anterior putamen (Z = −1.7 ± 1.5) or caudate (Z = −1.1 ± 1.0). Five of the 11 participants with RBD had abnormal Z scores in the posterior putamen in both hemispheres at baseline and follow-up assessment (RBD_3, 4, 7, 8, and 9), and one participant had abnormal Z scores in both hemispheres only in follow-up (RBD_11). The same 5 participants had abnormal Z scores in the anterior putamen in both hemispheres at baseline; however, this remained abnormal in only 3 participants at follow-up (RBD_3, 7, and 8). Finally, participant RBD_3 had abnormal Z scores in the caudate in both hemispheres at baseline; however, this abnormality was reduced below −2.5 at follow-up, and participant RBD_8 had abnormal Z scores in the caudate at baseline and follow-up for only one hemisphere (eTable 3, links.lww.com/WNL/D167).

Correlation Between Clinical Scores and SUVR

Although lower SUVR is associated with a higher UPDRSMOTOR score generally, there was no correlation between the extent of nigrostriatal degeneration and UPDRSMOTOR score in PD (eTable 4, links.lww.com/WNL/D167). At baseline, the posterior putamen SUVR correlated with the UPDRSMOTOR score (r = −0.35, CI: [−0.65 to +0.03], p = 0.07); however, there were no other correlations between SUVR and UPDRSMOTOR in any other ROI at either assessment (eTable 5).

Annual SUVR Decline in REM Sleep Behavior Disorder and Parkinson Disease

In the PD group, there was a significant difference in SUVR annual change in the posterior putamen (p < 0.0001, d = 0.4, ↓21.3% from baseline), anterior putamen (p = 0.0003, d = 0.4, ↓17.3% from baseline), and caudate (p = 0.03, d = 0.3, ↓9.3% from baseline) compared with NC (Figure 2A). There were no significant differences in SUVR in any ROI in the NC and RBD groups between baseline and follow-up (Table 2). The 18F-AV-133 SUVR annual rate of change as a function of baseline SUVR of the NC and PD groups in the posterior putamen, anterior putamen, and caudate with the RBD data overlaid on the curves is presented in Figure 2B. All subplots displayed a similar inverted U-shape curve, with a decreasing curvature from the posterior putamen to the anterior putamen and the caudate. PD and NC were highly discriminated in the posterior putamen, less in the anterior part, and even less in the caudate.

Figure 2. VMAT2 18F-AV-133 SUVR Annual Change in the REM Sleep Behavior Disorder and Parkinson Disease Brain.

(A) Annual change in the posterior and anterior putamen and caudate of all groups. Boxplot horizontal lines represent the median and whiskers represent minimum and maximum values. (B) Annual SUVR change as a function of the baseline SUVR in the posterior putamen, anterior putamen, and caudate. Data are presented as scatter plots. A second-order polynomial was fitted to the data and displayed as a black curve with confidence intervals in gray. RBD data points are overlaid on curves. Dotted line represents neurologic control (NC) mean. PD = Parkinson disease; RBD = REM sleep behavior disorder; SUVR = standardized uptake value ratio. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Correlation Between Annual Change in SUVR and Clinical Motor Scores

A correlation analysis of the annual SUVR and UPDRSMOTOR changes were performed for the PD group. There were no significant correlations between annual SUVR change in any ROI and annual change in UPDRSMOTOR (eTable 6, links.lww.com/WNL/D167).

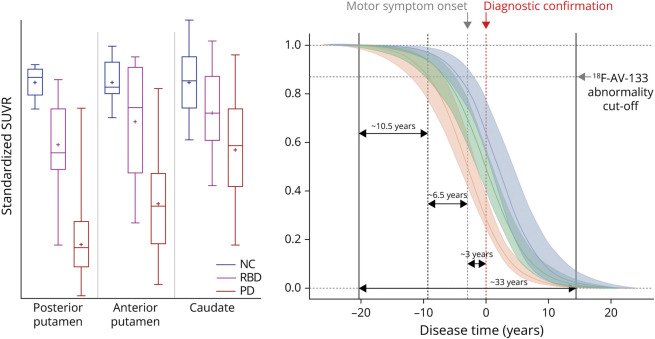

The Natural Progression of Parkinson Disease

Figure 3 presents the 18F-AV-133 SUVR trajectory curves along the PD continuum. The trajectory curves represent a standardized loss of SUVR at a given time point. This model indicates that it takes ∼10.5 years [CI: 9.1–11.3] from the beginning of decline for an individual to reach abnormality on a VMAT2 scan. It takes a further ∼6.5 years [CI: 1.6–12.7] to go from the abnormality threshold on one of the posterior putamen's to the onset of symptoms and a further ∼3 years [CI: 0.3–8.7] to the confirmation of a diagnosis of PD, with ∼33 years [CI: 27.2–39.5] for the full degenerative course. On average, the anterior putamen degenerative course is ∼2.5 years after the posterior putamen, and the caudate degenerative course is ∼1 year after the anterior putamen.

Figure 3. Standardized VMAT2 18F-AV-133 SUVR Plots and Trajectory Curves Along the Parkinson Disease Continuum.

Boxplot horizontal lines represent the median, whiskers reflect minimum and maximum values, and plus sign represents the mean. Perforated red line represents the average point of clinical diagnosis (time 0), perforated green line represents the average point of motor symptom onset, and shaded portion represents CI. Calculations for posterior putamen are based on individual hemispheres; posterior putamen: NC N = 13, RBD N = 18, and PD N = 52; anterior putamen: NC N = 8, RBD N = 16, and PD N = 44; and caudate: NC N = 14, RBD N = 16, and PD N = 42. NC = neurologic control; PD = Parkinson disease; RBD = REM sleep behavior disorder; SUVR = standardized uptake value ratio.

Sample Size Required for Neuroprotective Clinical Trials

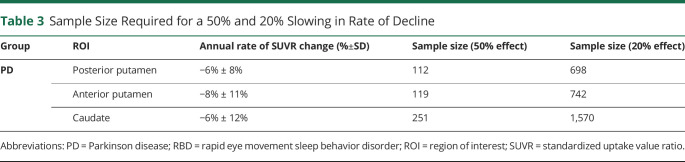

Based on the ligand binding data generated in this study, the average annual rate of SUVR change was used to estimate sample sizes required for a therapeutic trial to detect an effect size change of 50% or 20% in a PD group (Table 3). To detect a 50% reduction in rate of decline in the posterior putamen a trial would require 112 participants, 119 for the anterior putamen, and 251 for the caudate. To detect a 20% reduction in the rate of decline in the posterior putamen a trial would require 698 participants, 742 for the anterior putamen, and 1,570 for the caudate.

Table 3.

Sample Size Required for a 50% and 20% Slowing in Rate of Decline

| Group | ROI | Annual rate of SUVR change (%±SD) | Sample size (50% effect) | Sample size (20% effect) |

| PD | Posterior putamen | −6% ± 8% | 112 | 698 |

| Anterior putamen | −8% ± 11% | 119 | 742 | |

| Caudate | −6% ± 12% | 251 | 1,570 |

Abbreviations: PD = Parkinson disease; RBD = rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder; ROI = region of interest; SUVR = standardized uptake value ratio.

This study provides Class IV evidence that VMAT2 PET can detect patients with PD and quantify progression over a 2-year window.

Discussion

Sensitive measures of nigrostriatal degeneration in PD will improve our understanding of the natural history of disease and enhance our ability to monitor the efficacy of neuroprotective therapies. A substantial impairment in synaptic integrity at the point of clinical diagnosis has contributed to the absence of approved disease-modifying therapies in PD as it is estimated that dopamine transporter (DAT) density has decreased by as much as 60% at the time of clinical diagnosis as determined by postmortem analysis.21 In this study, we have replicated our previous findings that the VMAT2 tracer 18F-AV-133 was able to detect degeneration in the posterior putamen, anterior putamen, and caudate of participants with clinically diagnosed PD and RBD.6,18 Supporting our previous reports,15,18 the most severe degeneration was observed in the posterior putamen (>80% loss), followed by the anterior putamen (∼70% loss) and the caudate nucleus (∼60% loss) at the time of diagnosis.

Although the UPDRSMOTOR scores did not change between baseline and follow-up assessments in the PD group, there was a measurable decline in VMAT2 SUVR in all 3 brain regions. Sensitive markers that can faithfully reflect advancing neurodegeneration in PD are of the utmost priority for clinical trials because there is a lack of sensitivity in motor assessments to ongoing degeneration. Indeed, the reliability of the UPDRS to monitor progression of PD has been widely contested. A study of 362 patients with de novo PD were examined and demonstrated a linear increase in UPDRS score over 5 years with an average 4.7 points/year, with the UPDRSMOTOR score increasing by 2.4 points/year.22 These findings were not replicated in our study with an average UPDRSMOTOR score increase of 0.44, with 12 of 14 participants with PD scoring the same or lower on the UPDRSMOTOR examination at follow-up, albeit in a far smaller participant group in our study. Recently, Regnault et al. demonstrated the limited precision of the UPDRSMOTOR to detect the subtle changes in motor symptoms, especially in recently diagnosed PD,23 and Evers et al.24 calculated a high level of error variance from within-subject reliability. Although the UPDRSMOTOR is a useful tool in identifying overt parkinsonism, it is not sensitive enough to monitor advancing neurodegeneration nor to serve as a neuroprotective readout, especially in smaller scale phase II clinical trials.

Importantly, we have demonstrated the ability of 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET imaging to detect significant reduction in VMAT2 concentration across a span of only 2 years. The annual decline in the VMAT2 SUVR presented in the U-curves in Figure 3 display the annual change in VMAT2 SUVR as a function of baseline VMAT2 SUVR readings in all 3 regions. There is substantial separation of the NC and PD data in the posterior putamen. This separation is reflective of a skewed ‘floor effect’ in the posterior putamen of the PD group that is, the degeneration in this region of the brain in clinically overt PD is so advanced that there is little scope for further measurable synaptic loss in this region over time. The dichotomous nature of these data suggests that VMAT2 imaging of the posterior putamen is a good diagnostic tool, but the floor effect emphasizes that this region has limited ability to act as a prognostic and/or theragnostic marker.

Conversely, in the anterior putamen, there is a continuous distribution with many participants still in a ‘dynamic’ decline phase of the disease. In all groups, there is greater variance in the caudate, and even in advanced PD cases, there is not a large reduction in the SUVR despite annual decline plateauing to zero (48% in the caudate compared with 80% in the posterior putamen). These data suggest that the caudate may be generally less affected by degeneration in PD. While this makes it a more challenging region for diagnostic purposes because of the overlap between groups, regional monitoring may provide a better opportunity to measure the slowing of neurodegenerative processes because the anterior putamen and caudate are actively declining and yet to reach a “floor effect”. More importantly, this shows that including patients with clinically overt PD in a disease-modifying trial would likely show little or no benefit.

Nigrostriatal degeneration in PD has been previously assessed using 123I-β-CIT SPECT and 18F-FDOPA PET,8-10 and estimates as to the length of latency between onset of neurodegeneration and onset of motor impairment have been varied. Back projection of the decay slopes in the nigrostriatal region has been estimated as 3 years (range 2.8–6.5 years),8 5.6 ± 3.2 years,25 6.5 years (posterior putamen),11 and 5–7 years.26 In this study, using the ligand-binding observations across 2 time points from the NC and PD groups, we standardized the data and modeled the natural history of progressive nigrostriatal terminal degeneration in PD. Our model demonstrates a nonlinear sigmoidal decrease in dopaminergic terminals, which is in line with previous neuroimaging reports that neurodegeneration slows down during the course of disease.14,27 These trajectory models show for the first time that, on average, there is ∼10.5 years of degeneration in the posterior putamen before an abnormal VMAT2 scan would be observed. This finding highlights the critical need to identify readily available biomarkers that can be used in conjunction with the presentation of nonmotor symptoms of PD to identify people in the very early stages of neurodegeneration when neuroprotective agents will be their most effective.

The extensive time between onset of degeneration and clinical presentation poses as both a problem (to identify patients) and an opportunity (to intervene in the disease). The substantial loss before diagnosis suggests that undertaking trials of disease-modifying treatments beyond this are likely to prove problematic with a small likelihood of successful outcomes. It is not financially or practically feasible to scan people en masse. However, these models exhibit the utility of 18F-AV-133 to identify those at greater risk of developing PD, as is demonstrated by the relative position of the RBD cohort between an abnormal VMAT2 SUVR level and the average point of clinical diagnosis on the PD trajectory. In light of this, longitudinal clinical cohort studies in patients with RBD may allow for biomarker discovery that can be translated to patients with non-RBD prodromal PD and allow stratification of the population for sensitive VMAT2 PET scans.

These curves encapsulate the span of the degenerative process and demonstrate slow initial deterioration followed by accelerated decline through a dynamic phase of degeneration, before slowing and reaching a floor in the final stages. From the time of abnormal scan, it is ∼9 years until the onset of overt motor symptoms and ∼12 (±4) years until clinical diagnosis of PD. On the basis of this model, the overall degenerative course of PD is ∼33 years (to go from 100% to 0% SUVR).

Our calculated latency period of 22.5 years between onset of neurodegeneration and diagnosis is longer than previous predictions, and this may reflect the imaging modality because previous findings are based on 123I-β-CIT SPECT and 18F-FDOPA PET. 123I-β-CIT SPECT assesses the concentration of DAT, and VMAT2 is less susceptible than DAT to pharmacologic challenges and compensatory changes associated with the loss of dopaminergic neurons.28 F-DOPA is a tracer that is converted to 18F-fluorodopamine which provides a readout for dopamine synthesis capacity, which is more susceptible to upregulation as a compensatory mechanism for neuronal loss.29 In addition, the quantification of 18F-FDOPA PET is complex and requires dynamic imaging which prolongs scanning time and increases the likelihood of unavoidable patient movements confounding results.30

Our findings indicate the superior sensitivity of 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET as a marker of disease progression compared with clinical assessments in as short as 2 years. Based on the sensitivity of 18F-AV-133 PET, we calculated the sample size required for a clinical trial. Given the aforementioned limitations of relying on the posterior putamen in clinically overt PD, a 50% slowing of degeneration in the anterior putamen can be detected in a cohort of 119 patients with PD, and a 20% slowing can be detected in a cohort of 742 patients with PD.

The main limitations of this study are the relatively small number of participants with RBD and NC participants, as well as the lack of polysomnography to confirm the extent of RBD. Unexpectedly, we did see a small consistent increase in SUVR over time in the NC group. Despite careful re-examination of the data, we could not find an explanation for this, but it should be noted that many controls were taking multiple medications. A small population size, as well as an exclusively male RBD subpopulation, may reduce the generalizability of these findings to a broader, more diverse population. Because of the small sample size, especially our asymptomatic participants, we could not control our analysis for normal aging and sex. VMAT quantification has been reported to be lower in older individuals. In our analysis, symptomatic individuals are younger than the controls, so the age effect may have lowered the effect sizes reported here between control and patients with RBD and PD. It is also important to note that 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET may not be reflective of the true extent of nigrostriatal degeneration in the early stages of disease (i.e., the RBD group) because mechanisms such as sprouting of terminals may be compensating for the progressive neuronal/terminal loss.16,17 Of note, the participants with PD in this study were referred to the CUPS study because of their atypical presentation. Although they were later confirmed as PD by a neurologist and VMAT2 scans, this may limit the generalizability of our findings to more typical presentations of PD and have increased the time from symptom onset to diagnosis. This is supported by a recent study into the determinants of delayed diagnosis in PD which found a median time of 11 months between symptom onset and primary care physician presentation, although the range for these data was substantial (0–100 months).31 As neuroimaging remains costly and access to tracers such 18F-AV-133 is limited, reliance on imaging will be restricted to high-income regions. Moving forward, it would be of benefit to assess peripheral biomarkers to increase accessibility of PD diagnostics and monitoring globally, and VMAT2 PET imaging will aid in the validation of these markers.

To conclude, assessing nigrostriatal integrity with 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET shows promise as a tool to monitor therapeutic response in disease-modifying trials. Furthermore, 18F-AV-133 is a sensitive means to identify individuals at risk of progression to PD and could aid stratification in a cohort of patients with RBD in the degenerative phase of disease to study the natural history of PD and allow biomarker discovery within the optimal therapeutic window.

Glossary

- CUPS

clinically uncertain parkinsonian syndrome

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- NC

neurologic controls

- PD

Parkinson disease

- RBD

REM sleep behavior disorder

- ROI

region of interest

- SPECT

single-photon emission computed tomography

- SUVR

standard uptake value ratio

- VMAT2

vesicular monoamine transporter type 2

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Leah C. Beauchamp, PhD | The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Vincent Dore | Health & Biosecurity Flagship, The Australian eHealth Research Centre, The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Victor L. Villemagne | Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh. PA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| SanSan Xu, MD | Department of Neurology, Austin Health, Melbourne, Australia | Major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| David Finkelstein, PhD | The Florey institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health; The University of Melbourne, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Kevin J. Barnham | The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Christopher Rowe | Department of Molecular Imaging and Therapy, Austin Health, Melbourne, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Footnotes

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

Study Funding

NHMRC Program APP1132604.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Scherman D, Desnos C, Darchen F, Pollak P, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y. Striatal dopamine deficiency in Parkinson's disease: role of aging. Ann Neurol. 1989;26(4):551-557. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee CS, Samii A, Sossi V, et al. In vivo positron emission tomographic evidence for compensatory changes in presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(4):493-503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1591-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach TG, Adler CH. Importance of low diagnostic accuracy for early Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33(10):1551-1554. doi: 10.1002/mds.27485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeed U, Lang AE, Masellis M. Neuroimaging advances in Parkinson's disease and atypical parkinsonian syndromes. Front Neurol. 2020;11:572976. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.572976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander PK, Lie Y, Jones G, et al. Management impact of imaging brain vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 in clinically uncertain parkinsonian syndrome with (18)F-AV133 and PET. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(11):1815-1820. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.189019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu SS, Alexander PK, Lie Y, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of imaging brain vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) in clinically uncertain parkinsonian syndrome (CUPS): a 3-year follow-up study in community patients. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e025533. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrish PK, Rakshi JS, Bailey DL, Sawle GV, Brooks DJ. Measuring the rate of progression and estimating the preclinical period of Parkinson's disease with [18F]dopa PET. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64(3):314-319. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.3.314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrish PK, Sawle GV, Brooks DJ. An [18F]dopa-PET and clinical study of the rate of progression in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 2):585-591. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vingerhoets FJ, Snow BJ, Lee CS, Schulzer M, Mak E, Calne DB. Longitudinal fluorodopa positron emission tomographic studies of the evolution of idiopathic parkinsonism. Ann Neurol. 1994;36(5):759-764. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nurmi E, Ruottinen HM, Bergman J, et al. Rate of progression in Parkinson's disease: a 6-[18F]fluoro-L-dopa PET study. Mov Disord. 2001;16(4):608-615. doi: 10.1002/mds.1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marek K, Innis R, van Dyck C, et al. [123I]beta-CIT SPECT imaging assessment of the rate of Parkinson's disease progression. Neurology. 2001;57(11):2089-2094. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.11.2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staffen W, Mair A, Unterrainer J, Trinka E, Ladurner G. Measuring the progression of idiopathic Parkinson's disease with [123I] beta-CIT SPECT. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2000;107(5):543-552. doi: 10.1007/s007020070077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirker W, Djamshidian S, Asenbaum S, et al. Progression of dopaminergic degeneration in Parkinson's disease and atypical parkinsonism: a longitudinal beta-CIT SPECT study. Mov Disord. 2002;17(1):45-53. doi: 10.1002/mds.1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villemagne VL, Okamura N, Pejoska S, et al. In vivo assessment of vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 in dementia with lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(7):905-912. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto M, Masliah E. Cycles of aberrant synaptic sprouting and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurochem Res. 2003;28(11):1743-1756. doi: 10.1023/a:1026073324672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelstein DI, Stanic D, Parish CL, Tomas D, Dickson K, Horne MK. Axonal sprouting following lesions of the rat substantia nigra. Neuroscience. 2000;97(1):99-112. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00009-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beauchamp LC, Villemagne VL, Finkelstein DI, et al. Reduced striatal vesicular monoamine transporter 2 in REM sleep behavior disorder: imaging prodromal parkinsonism. Scientific Rep. 2020;10(1):17631. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74495-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones G, Villemagne V, Pejoska S, O'Keefe G, Rowe C. Automatic image analysis of AV133 PET images. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(supplement 1):2319. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, et al. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(4):357-367. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70044-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg D, Marek K, Ross GW, Poewe W. Defining at-risk populations for Parkinson's disease: lessons from ongoing studies. Mov Disord. 2012;27(5):656-665. doi: 10.1002/mds.24985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holden SK, Finseth T, Sillau SH, Berman BD. Progression of MDS-UPDRS scores over five years in de novo Parkinson disease from the Parkinson's progression markers initiative cohort. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2018;5(1):47-53. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regnault A, Boroojerdi B, Meunier J, Bani M, Morel T, Cano S. Does the MDS-UPDRS provide the precision to assess progression in early Parkinson's disease? Learnings from the Parkinson's progression marker initiative cohort. J Neurol. 2019;266(8):1927-1936. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09348-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evers LJW, Krijthe JH, Meinders MJ, Bloem BR, Heskes TM. Measuring Parkinson's disease over time: the real-world within-subject reliability of the MDS-UPDRS. Mov Disord. 2019;34(10):1480-1487. doi: 10.1002/mds.27790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilker R, Schweitzer K, Coburger S, et al. Nonlinear progression of Parkinson disease as determined by serial positron emission tomographic imaging of striatal fluorodopa F 18 activity. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(3):378-382. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chouker M, Tatsch K, Linke R, Pogarell O, Hahn K, Schwarz J. Striatal dopamine transporter binding in early to moderately advanced Parkinson's disease: monitoring of disease progression over 2 years. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22(6):721-725. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200106000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakakibara S, Hashimoto R, Katayama T, et al. Longitudinal change of DAT SPECT in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(1):123-130. doi: 10.3233/jpd-191710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eshuis SA, Jager PL, Maguire RP, Jonkman S, Dierckx RA, Leenders KL. Direct comparison of FP-CIT SPECT and F-DOPA PET in patients with Parkinson's disease and healthy controls. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(3):454-462. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0989-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrish PK, Sawle GV, Brooks DJ. Clinical and [18F] dopa PET findings in early Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59(6):597-600. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.59.6.597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan XB, Wright TG, Leong FJ, McLaughlin RA, Declerck JM, Silverman DH. Improving influx constant and ratio estimation in FDOPA brain PET analysis for Parkinson's disease. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(10):1737-1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breen DP, Evans JR, Farrell K, Brayne C, Barker RA. Determinants of delayed diagnosis in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2013;260(8):1978-1981. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6905-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data used for this study are available on request by qualified investigators.