Abstract

Background

Scarce data exist on sex differences in patients with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events undergoing patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure. This study aimed to determine the sex differences in clinical profile, procedural characteristics, and long‐term outcomes of patients with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events undergoing PFO closure.

Methods and Results

A retrospective cohort was used, including 1076 consecutive patients undergoing PFO closure because of a cryptogenic cerebrovascular event. Patients were divided into 2 groups: 469 (43.6%) women and 607 (56.4%) men. The median follow‐up was 3 years (interquartile range, 2–8 years). Women were younger (46±13 versus 50±12 years; P<0.01) and had a higher risk of paradoxical embolism score (6.9±1.7 versus 6.6±1.6; P<0.01). Procedural characteristics and postprocedural antithrombotic therapy were similar. At follow‐up, there were no differences in atrial fibrillation (women versus men: 0.47 versus 0.97 per 100 patient‐years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.55 [95% CI, 0.27–1.11]; P=0.095; adjusted P=0.901), stroke (0.17 versus 0.07 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 2.58 [95% CI, 0.47–14.1]; P=0.274; adjusted P=0.201), or transient ischemic attack (0.43 versus 0.18 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 2.58 [95% CI, 0.88–7.54]; P=0.084; adjusted P=0.121); nevertheless, women exhibited a higher incidence of combined ischemic cerebrovascular events (0.61 versus 0.26 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 2.58 [95% CI, 1.04–6.39]; P=0.041; adjusted P=0.028) and bleeding events (1.04 versus 0.45 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 2.82 [95% CI, 1.41–5.65]; P=0.003; adjusted P=0.004).

Conclusions

Compared with men, women with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events undergoing PFO closure were younger and had a higher risk of paradoxical embolism score. After a median follow‐up of 3 years, there were no differences in stroke events, but women exhibited a higher rate of combined (stroke and transient ischemic attack) cerebrovascular events and bleeding complications. Additional studies are warranted to clarify sex‐related outcomes after PFO closure further.

Keywords: cryptogenic stroke, patent foramen ovale, sex differences

Subject Categories: Ischemic Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA), Treatment, Women, Congenital Heart Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

- PFO

patent foramen ovale

- RoPE

risk of paradoxical embolism

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Women with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events undergoing patent foramen ovale closure, compared with men, are younger, have a higher paradoxical embolism risk score, and have more migraines.

Despite similar procedural results, women seem to present higher incidences of bleeding events at follow‐up, with no difference in the rate of recurrent stroke or transient ischemic attack; however, the rate of combined cerebrovascular events (stroke+transient ischemic attack) seems to be higher among women than men.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Sex differences in patients with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events undergoing patent foramen ovale closure urge for sex‐related risk factor consideration on potential additional mechanisms of cerebral ischemia among young female patients with a patent foramen ovale.

The selection of long‐term antithrombotic therapy after patent foramen ovale closure should be made considering sex‐specific ischemic and bleeding risk factors and contemplating a potential increased risk of bleeding among female patients.

Male and female patients have substantial differences in stroke‐related risk factors, including genetic differences in immunity, coagulation, hormonal factors, reproductive factors, such as pregnancy, childbirth, and social factors, all of which can influence the risk for stroke and impact clinical outcomes. 1 , 2 Some of these baseline differences have also been previously reported in patients with cryptogenic stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) and patent foramen ovale (PFO). 3

Although a large amount of data exist on sex differences in outcomes of several congenital heart diseases, 4 , 5 , 6 information on sex differences in patients undergoing transcatheter PFO closure is limited, given the presence of a PFO is considered normal or an anatomic variant 7 ; thus, it was not addressed in ancient studies nor is it addressed in current clinical guidelines on the management of adults with congenital heart disease. 7 , 8 For patients with cryptogenic stroke, only Canadian guidelines 9 on stroke management and 1 specific PFO management position article 10 partially addressed sex‐difference considerations in patients with PFO‐related stroke.

The only retrospective study evaluating sex differences in outcomes following PFO closure showed no differences according to sex, but the follow‐up was limited to 3 months. 11 However, recent studies reported additional sex differences among patients undergoing PFO closure, such as potential differences in device size, 12 delayed PFO closure in female patients, 13 and a higher rate of postprocedural atrial fibrillation (AF) among male patients. 14

Most important, several metanalyses 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 have shown, although from subgroup analyses, that a causal role of PFO in cryptogenic stroke is more probable in male patients because male patients presented a larger benefit in clinical outcomes after transcatheter PFO closure compared with female patients.

Thus, the objective of our study was to determine the sex differences in clinical profile, procedural characteristics, and long‐term outcomes of patients with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events undergoing PFO closure.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study that included consecutive patients diagnosed with a cryptogenic cerebrovascular event who underwent transcatheter PFO closure between January 23, 2000 and December 23, 2020 in 2 tertiary university centers. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The diagnosis of PFO was established on the basis of a right‐to‐left shunt during the transesophageal echocardiographic examination by performing the agitated saline test with and without the Valsalva maneuver. A neurologist made the diagnosis of cerebrovascular PFO‐related events (ischemic stroke or TIA) in all cases. The relationship of the primary neurologic event with the PFO was established after excluding all other potential causes for the neurologic event via a thorough screening, including brain computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or both, 24‐hour (or more) Holter monitoring, transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography, and transcarotid Doppler. Patients with preexistent AF were excluded from this study. Transcatheter PFO closure was performed under fluoroscopic and echocardiographic guidance, and the choice of closure device was left to the implanters' physician criteria. Medical treatment at discharge was left to the treating physicians' criteria.

Data were gathered in a dedicated database at each participating center. Data were collected from in‐hospital medical records and national and regional public health registries to ensure accurate follow‐up. Patients had a clinical follow‐up (clinical visits or telephonic medical appointment at 1‐ and 12‐month follow‐up, and yearly thereafter), and a complete revision of each patient's medical file was performed for anonymized data collection. The information gathered was directed toward clinically significant events related to PFO closure, including overall mortality, cardiovascular mortality, new or recurrent thromboembolic events, such as ischemic stroke, TIA, and peripheral embolism, bleeding events, symptomatic AF, and cardiovascular events. In cases where a clinical event was identified, the complete medical record in the main follow‐up center was reviewed as needed. The primary care physician, cardiologist, or neurologist was consulted if additional information was required.

The stroke diagnosis was confirmed with either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. A TIA was diagnosed following the tissue‐based definition in the presence of a transient episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia without acute infarction. 20 All neurologic events were diagnosed by a neurologist. All bleeding events were collected and classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria 21 as major (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium 3–5) or minor (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium 1–2). Procedural AF was defined as AF occurring during the PFO closure procedure, whereas follow‐up AF was considered when symptomatic and documented episodes of AF occurred after hospital discharge. All patients provided signed informed consent for the procedures. The study was performed following the Ethics Committee's approval of each participating center, and the informed consent for data collection was waived because of the retrospective and anonymous nature of data collection for the structural heart disease database. We have used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) cohort reporting guidelines when writing our report. 22

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were reported as number (percentage), and continuous variables were reported as mean±SD. Comparisons were made with χ2, Fisher, or Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. A Poisson regression analysis was performed to compare the effect of sex on clinical outcomes. To account for baseline differences between men and women, a propensity score adjustment was performed. The final model included age, hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, device size, antiplatelets, and oral anticoagulants at discharge as retained variables. The goodness‐of‐fit test using the Hosmer‐Lemeshow test indicated that the final model was well fitted (χ 2=4.52; df=8; P=0.81). The propensity score was included as an independent variable in the regression models to address confounding effects. Adjusted P values were obtained using the propensity score adjustment to account for confounding effects. Survival curves for time‐to‐event variables were performed using Kaplan‐Meier estimates, and the log‐rank test was used for group comparisons. Results were considered significant at P<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

From 1136 consecutive patients who underwent PFO closure, 60 (5.3%) were excluded as their primary indication for PFO closure was other than a PFO‐related cerebrovascular event. Of the remaining 1076 patients, 607 (56.4%) men and 469 (43.6%) women (sex ratio, 1.29 men/women) underwent transcatheter PFO closure attributable to a cryptogenic stroke or TIA. The baseline characteristics of both groups are summarized in Table 1. Female patients were younger (46±13 years versus 50±12 years for men; P<0.01), had a higher rate of prior migraine (25.4% versus 11.5% for men; P<0.01), and had a higher risk of paradoxical embolism (RoPE) score (6.91 versus 6.59 for men; P<0.01). On the contrary, male patients exhibited a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia (24.1% versus 13.9%; P<0.01) and coronary artery disease (3.5% versus 0.4%; P<0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population, According to Sex

| Characteristic | Male patients (n=607) | Female patients (n=469) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 49.5±11.8 | 46.4±13.3 | <0.01 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.97±0.17 | 1.74±0.18 | <0.01 |

| Smoking, current | 66 (10.9) | 46 (9.8) | 0.57 |

| Hypertension | 123 (20.3) | 89 (18.9) | 0.60 |

| Diabetes | 30 (4.9) | 15 (3.2) | 0.16 |

| Dyslipidemia | 146 (24.1) | 65 (13.9) | <0.01 |

| Previous coronary artery disease | 21 (3.5) | 2 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| Prior migraine | 70 (11.5) | 119 (25.4) | <0.01 |

| History of pulmonary embolism | 20 (3.3) | 17 (3.6) | 0.77 |

| History of deep vein thrombosis | 39 (6.4) | 32 (6.8) | 0.79 |

| History of thrombophilia | 41 (6.8) | 28 (6.0) | 0.61 |

| Shunt preprocedure | |||

| Mild | 58 (9.6) | 54 (11.5) | 0.28 |

| Moderate/severe | 527 (86.8) | 395 (84.2) | 0.28 |

| Atrial septal aneurysm* | 256 (52.9) | 219 (55.7) | 0.40 |

| RoPE score | 6.59±1.61 | 6.91±1.69 | <0.01 |

| PFO closure indication | |||

| Stroke | 514 (84.7) | 384 (81.9) | 0.22 |

| TIA | 105 (17.3) | 93 (19.8) | 0.29 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or absolute number (percentage). PFO indicates patent foramen ovale; RoPE, risk of paradoxical embolism; and TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Data on atrial septal aneurysm are available in 877 patients.

Procedural characteristics of transcatheter PFO closure between groups are shown in Table 2. All procedures were successful, and the most frequently implanted device in the study population was the Amplatzer PFO occluder (Abbott, Chicago, IL). There were no differences between groups in procedural complications, discharge medications, or residual shunt rate.

Table 2.

Procedural Characteristics and In‐Hospital Outcomes, According to Sex

| Variable | Male patients (n=607) | Female patients (n=469) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful implantation | 607 (100) | 469 (100) | … |

| Device type | |||

| Amplatzer PFO | 483 (79.6) | 363 (77.4) | 0.389 |

| Amplatzer ASD | 23 (3.8) | 28 (5.9) | 0.095 |

| Amplatzer cribriform | 17 (2.8) | 15 (3.2) | 0.703 |

| Premere | 11 (1.8) | 8 (1.7) | 0.895 |

| Occlutech | 62 (10.2) | 46 (9.8) | 0.826 |

| Device size ≥25 mm | 583 (96.1) | 444 (94.7) | 0.282 |

| Procedural complications | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (0.9) | 3 (0.6) | 0.739 |

| Embolization | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.999 |

| Intracardiac thrombus | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.999 |

| Access site bleeding | 4 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | 0.734 |

| Medical treatment at discharge | |||

| Aspirin | 514 (84.7) | 398 (84.9) | 0.732 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 277 (45.6) | 200 (42.6) | 0.245 |

| Oral anticoagulation | 61 (10.0) | 44 (9.4) | 0.611 |

| Follow‐up residual shunt | 39 (6.4) | 31 (6.6) | 0.903 |

Data are expressed as absolute number (percentage). ASD indicates atrial septal defect; and PFO, patent foramen ovale.

The median follow‐up of the entire study population was 3 (interquartile range, 2–8) years, and it was complete in 99.5% and 99.8% of male and female patients, respectively. The main clinical outcomes according to sex are shown in Table 3. There were no differences in mortality between groups (women, 0.46 per 100 patient‐years; men, 0.44 per 100 patient‐years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.18 [95% CI, 0.52–2.68]; P=0.69; adjusted P=0.41); none of the outcomes were of cardiovascular origin. There were 11 deaths (2.4%) in the female group and 12 (1.9%) in the male group. The most common cause of death was cancer, with 5 cases in each group.

Table 3.

Incidence and IRRs for Events Over the Follow‐Up Period, According to Sex

| Event | Incidence (per 100 patient‐years) | IRR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female patients | Male patients | ||||

| Death | 0.46 | 0.44 | 1.18 (0.52–2.68) | 0.690 | 0.411 |

| Cerebrovascular events | 0.61 | 0.26 | 2.58 (1.04–6.39) | 0.041 | 0.028 |

| Stroke | 0.17 | 0.07 | 2.58 (0.47–14.1) | 0.274 | 0.201 |

| TIA | 0.43 | 0.18 | 2.58 (0.88–7.54) | 0.084 | 0.121 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.47 | 0.97 | 0.55 (0.27–1.11) | 0.095 | 0.901 |

| Bleeding | 1.04 | 0.45 | 2.82 (1.41–5.65) | 0.003 | 0.004 |

IRR indicates incidence rate ratio; and TIA, transient ischemic attack.

P values were obtained using the propensity score adjustment.

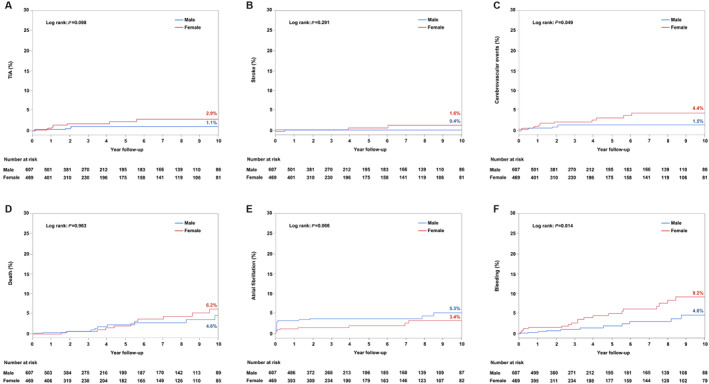

There were no differences in the rates of recurrent stroke (0.17 versus 0.07 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 2.58 [95% CI, 0.47–14.1]; P=0.274; adjusted P=0.201) or TIA (0.43 versus 0.18 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 2.58 [95% CI, 0.88–7.54]; P=0.084; adjusted P=0.121) between groups; however, after a secondary analysis of combined neurologic outcomes (stroke and TIA), there was a higher incidence of combined cerebrovascular events among women (0.61 versus 0.26 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 2.58 [95% CI, 1.04–6.39]; P=0.041), which persisted after adjustment (P=0.028). All stroke events were ischemic strokes. There were no significant differences between groups in the occurrence of symptomatic AF episodes at follow‐up (women, 0.47 per 100 patient‐years; men, 0.97 per 100 patient‐years; IRR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.27–1.11]; P=0.095; adjusted P=0.901). The incidence of bleeding events was higher among women, with 1.04 versus 0.45 per 100 patient‐years among men (IRR, 2.82 [95% CI, 1.41–5.65]; P=0.003), which remained significant after adjustment (P=0.004; Figure 1). There was no difference in the severity of bleeding between groups; women presented 8 (33.3%) major and 16 (66.7%) minor bleeding events, whereas men presented 6 (50%) and 6 (50%), respectively (P=0.472). At the last follow‐up, 62.3% of women were taking aspirin, versus 72.6% of men (P=0.003); P2Y12 inhibitors were taken by 9.7% of women versus 9.5% of men (P=0.901), and oral anticoagulation were taken by 10.8% versus 10.1%, respectively (P=0.810).

Figure 1. Kaplan‐Meier curves for clinical events at 10‐year follow‐up.

Long‐term 10‐year clinical outcome comparison between women and men after transcatheter patent foramen ovale closure: transient ischemic attack (TIA) (A); stroke (B); cerebrovascular events (C); death (D); atrial fibrillation (E); and bleeding (F).

The Kaplan‐Meier curves for clinical events at 10‐year follow‐up are shown in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

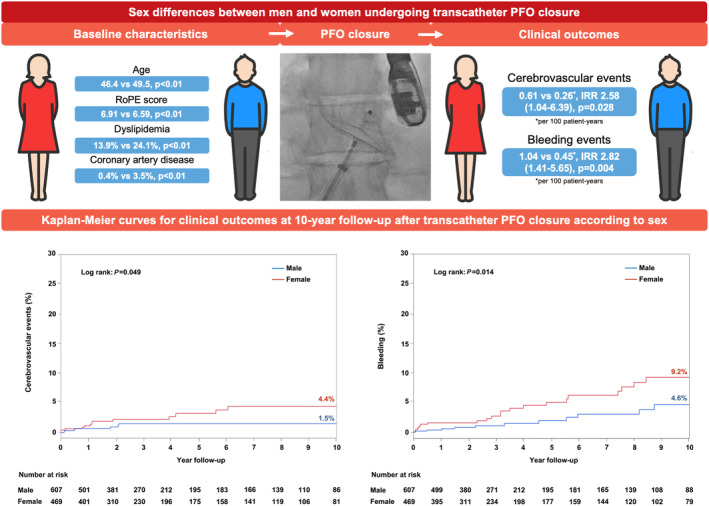

The findings of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) male and female patients undergoing transcatheter PFO closure for cryptogenic stroke or TIA exhibited similar baseline characteristics, except for a younger age (and consequently, a higher RoPE score) and a higher rate of prior migraine attacks among female patients; (2) there were no differences between groups in procedural success (100%) and complications (<1%), antithrombotic treatment, and rate of residual shunting after the procedure; (3) after a median follow‐up of 3 years, women exhibited a higher rate (>2 times) of bleeding events, with no differences in mortality, stroke, or TIA between groups; however, the rate of combined ischemic cerebrovascular events was higher among women (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sex differences between men and women undergoing transcatheter patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure.

Women with a PFO‐related cryptogenic ischemic cerebrovascular event undergoing transcatheter PFO closure, compared with men, exhibit different baseline characteristics, such as younger age, higher risk of paradoxical embolism (RoPE) score, and higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease. They exhibit no differences in procedural characteristics. Nevertheless, at a median follow‐up of 3 years, women show higher incidences of ischemic cerebrovascular events (ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack combined) and bleeding events. IRR indicates incidence rate ratio.

Baseline Characteristics

In accordance with our results, previous studies showed a similar proportion of men and women undergoing PFO closure because of a cryptogenic thromboembolic event. 23 Some baseline differences, like the smaller surface area in women, reflect the biological differences between male and female individuals. 24 However, there is no clear explanation for age differences between groups. This difference has also been seen in a recent analysis of 19 studies focused on sex differences in stroke among young people. 25 Sex‐specific risk factors, such as changes in hormonal status in women according to age, gestational status, higher incidence of autoimmune diseases, and the potential use of hormonal therapies, 26 , 27 may have played a role in the younger age of women in our study. Nevertheless, the younger age of women in our study determined a higher RoPE score, which indicates a higher likelihood for the causal association between the PFO and the cerebrovascular event. 28 Notably, the mean RoPE score of the overall study population was 6.75, slightly lower than 7, which has been recently described as the ideal cutoff because this value indicates a higher causal association between the PFO and any given cerebrovascular event. 29 However, this scoring system has some limitations, and this cutoff point was defined after the completion of our study. Also, a RoPE score of 6 points has a PFO‐attributable fraction of 62 and an estimated stroke/TIA recurrence at 2 years of 8%. 28 The higher prevalence of migraine among women is well known; among healthy young women, the prevalence varies between 18% and 33%, whereas it is <10% in young men. 30 , 31 Also, migraine prevalence has been consistently higher among patients with PFO, 32 and several studies have shown that migraine may have a close relationship with PFO. 33

Procedural Characteristics

Similar to the results from this study, PFO closure success has been reported as high as 100% in recent studies, with a low rate of periprocedural complications. 15 Interestingly, Venturini et al described a predictive model for PFO device size selection considering 3 factors, atrial septum aneurism, PFO tunnel >10 mm, and male sex, all of them being predictors of a larger disk size for closure. 12 However, in our study, the proportion of patients with right disks >25 mm was similar between male and female patients. Also, the final optimal result determined by the absence of residual shunting by echocardiography was not influenced by sex.

Long‐Term Follow‐Up

After a median follow‐up of 3 years, although there were no differences in the rates of stroke or TIA as isolated outcomes, female patients undergoing transcatheter PFO closure had a higher rate of combined cerebrovascular events, and these differences remained significant after adjustment.

The only study that aimed to describe outcomes according to sex after transcatheter PFO closure had a mean follow‐up time of 89 days and showed no differences in cerebrovascular events between sexes. 11 The observed differences between men and women in our study on cerebrovascular outcomes were previously demonstrated as well in several meta‐analyses of transcatheter PFO closure versus medical therapy trials, 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 and these differences were interpreted as PFO closure having a larger benefit in male patients than in female patients. Male patients from these trials showed a lower incidence of cerebrovascular events after transcatheter PFO closure, as seen in our study, thus suggesting a more prominent causal role of PFO among male patients with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events.

The 100% success rate of PFO closure, the low rate of residual shunting, and the absence of differences in antithrombotic treatment between sexes in our study make it unlikely that cerebrovascular events after PFO closure are PFO‐related events. Sex differences in ischemic stroke are increasingly acknowledged. Women more often experience ischemic stroke compared with men at younger ages 25 and especially after menopause 1 ; furthermore, they have an increased risk of adverse outcomes. 34 The association between migraine and stroke is thought to be more prominent in patients without a traditional cardiovascular risk profile, 35 similar to the clinical profile observed in our overall study population. Alternative mechanisms not associated with atherosclerosis, like microembolisms, vasospasms in the microvasculature, and endothelial dysfunction, 36 may be involved in the pathophysiological characteristics of cerebrovascular events in these patients. Because other unidentified risk factors might exist, particularly among young patients with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events, the ongoing SECRETO (Searching for Explanations for Cryptogenic Stroke in the Young: Revealing the Etiology, Triggers, and Outcome) (NCT01934725) 37 study will provide important insights into this population.

Before adjustment, there was a tendency for a higher incidence of symptomatic AF among male patients; nevertheless, this difference was no longer significant after adjustment. A recent study by Guedeney et al showed a higher incidence of AF among male patients. However, the authors aimed to identify the actual incidence of the postprocedural rate of AF, half of which being asymptomatic, using a 4‐week loop recorder, 14 which could explain the difference with our results.

Female patients exhibited a higher incidence of bleeding events during follow‐up. This was seen even after the adjustment between groups. This is important because, per clinical management guidelines on PFO closure, patients undergoing PFO closure should also be treated with dual‐antiplatelet therapy for 1 to 6 months after the PFO closure, and it is recommended to continue with single‐antiplatelet therapy, typically aspirin, for at least 5 years after the procedure. On the contrary, in patients without PFO closure, typically, single‐antiplatelet therapy is recommended, except in special circumstances where dual‐antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation may be recommended. 10 Thus, at least in the first months after PFO closure, patients are exposed to an increased risk of bleeding attributable to the PFO‐closure postprocedural antithrombotic therapy. It has been shown that patients undergoing PFO closure plus medical therapy versus patients left under medical therapy alone have the same bleeding risk. 18 , 19 Nevertheless, among patients with PFO left under medical treatment, an increased risk of bleeding has been documented with oral anticoagulation compared with antiplatelet therapy 38 and confirmed in a meta‐analysis, which included 14 studies and 1426 patients. 10 However, the only study addressing sex differences following PFO closure failed to show any difference in bleeding events, but the mean follow‐up time was short. 11 Interestingly, premenopausal women can have a higher risk of bleeding than men when taking anticoagulation therapy. 39 Also, sexual dimorphism and age differences in human platelet aggregation dynamics are well known. 40 Women have a higher platelet reactivity at baseline, and the coagulation cascade is considerably influenced by fluctuations in hormone status under several different circumstances. 41 Because of our study design, we were unable to determine in this study if the increased rate of bleeding in women was related to the PFO closure status or if it reflects the underlying differences in bleeding rates between women and men. However, and most important, the concurrence of a higher incidence of cerebrovascular events and a higher incidence of bleeding events among female patients should encourage a better sex‐tailored treatment selection for patients with a PFO‐associated cerebrovascular event.

Study Limitations

Our study has several restraints; it represents a retrospective, nonprespecified analysis of prospectively collected data. In our study, whether periprocedural AF was transient or persistent was not defined, and no postprocedural long‐duration loop recorder was specifically used to identify the short‐term rate of AF. The proportion of patients undergoing specific arterial imaging during their computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or both workup was not collected. Although most patients completed the follow‐up, we recognize that some events (particularly minor) could have been missed; however, this would have likely had a similar impact in both (men and women) groups. TIA is known to be an important ischemic event and portends an increased risk of further stroke; however, because of its nature, diagnostic criteria, and similarity with different pathologic conditions, including migraine, which was more prevalent among female patients, its use as an outcome event remains limited by its own characteristics. Although all neurologic events were confirmed by a neurologist, including the TIA outcome, there was no event adjudication committee for this study. In addition, it is possible that some TIA events might have been complex migraines rather than true TIA events, especially when some types of migraine have been causally associated with PFO, cryptogenic stroke, and TIA. 35 For the bleeding events, although there was no difference in their severity, no information on the bleeding site was collected.

CONCLUSIONS

Female and male patients undergoing transcatheter PFO closure for cryptogenic stroke or TIA exhibited similar baseline characteristics, except for the younger age, higher RoPE score, and higher prevalence of prior migraine attacks among women. Despite the similar procedural success and residual shunting rates following PFO closure, women exhibited a higher incidence of bleeding events after a median follow‐up of 3 years. In addition, although there were no differences in the rates of stroke or TIA as isolated events, female patients had a higher rate of combined ischemic cerebrovascular events, a difference that remained significant after adjustment. These differences emphasize the urge for sex‐factor consideration on potential additional mechanisms of cerebral ischemia among young female patients with a PFO and the appropriate selection of long‐term antithrombotic therapy considering sex‐specific ischemic and bleeding risk factors. Also, the design of future trials on cryptogenic cerebrovascular events and PFO closure should include an appropriate sex‐tailored approach.

Sources of Funding

Dr. Rodés‐Cabau holds the Research Chair “Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière” for the Development of Structural Heart Disease Interventions.

Disclosures

Dr Rodés‐Cabau has received institutional research grants from Abbott Vascular Canada. Dr Montalescot reports research funds for the institution or fees from Abbott. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

This article was sent to Neel S. Singhal, MD, PhD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

See Editorial by Poisson et al.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see pages 8.

References

- 1. Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, Chireau MV, Fedder WN, Furie KL, Howard VJ, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Piña IL, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:1545–1588. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000442009.06663.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rexrode KM, Madsen TE, Yu AYX, Carcel C, Lichtman JH, Miller EC. The impact of sex and gender on stroke. Circ Res. 2022;130:512–528. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.121.319915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nedeltchev K, Wiedmer S, Schwerzmann M, Windecker S, Haefeli T, Meier B, Mattle HP, Arnold M. Sex differences in cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. Am Heart J. 2008;156:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engelfriet P, Mulder BJ. Gender differences in adult congenital heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2009;17:414–417. doi: 10.1007/bf03086294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verheugt CL, Uiterwaal CS, van der Velde ET, Meijboom FJ, Pieper PG, Vliegen HW, van Dijk AP, Bouma BJ, Grobbee DE, Mulder BJ. Gender and outcome in adult congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2008;118:26–32. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.758086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zomer AC, Ionescu‐Ittu R, Vaartjes I, Pilote L, Mackie AS, Therrien J, Langemeijer MM, Grobbee DE, Mulder BJ, Marelli AJ. Sex differences in hospital mortality in adults with congenital heart disease: the impact of reproductive health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, Bozkurt B, Broberg CS, Colman JM, Crumb SR, Dearani JA, Fuller S, Gurvitz M, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e637–e697. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu‐Narayan SV, Budts W, Chessa M, Diller GP, Lung B, Kluin J, Lang IM, Meijboom F, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:563–645. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gladstone DJ, Lindsay MP, Douketis J, Smith EE, Dowlatshahi D, Wein T, Bourgoin A, Cox J, Falconer JB, Graham BR, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: secondary prevention of stroke update 2020. Can J Neurol Sci. 2022;49:315–337. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2021.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pristipino C, Sievert H, D'Ascenzo F, Louis Mas J, Meier B, Scacciatella P, Hildick‐Smith D, Gaita F, Toni D, Kyrle P, et al. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3182–3195. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asghar A, Stefanescu‐Schmidt AD, Sahakyan Y, Horlick EM, Abrahamyan L. Sex differences in baseline profiles and short‐term outcomes in patients undergoing closure of patent foramen ovale. Am Heart J Plus. 2022;21:21. doi: 10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Venturini JM, Retzer EM, Estrada JR, Mediratta A, Friant J, Nathan S, Paul JD, Blair J, Lang RM, Shah AP. A practical scoring system to select optimally sized devices for percutaneous patent foramen ovale closure. J Struct Heart Dis. 2016;2:217–223. doi: 10.12945/j.jshd.2016.009.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guedeney P, Mesnier J, Zeitouni M, Hauguel‐Moreau M, Silvain J, Houde C, Alperi A, Panagides V, Collet JP, Wallet T, et al. Outcomes following patent foramen ovale percutaneous closure according to the delay from last ischemic event. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38:1228–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guedeney P, Laredo M, Zeitouni M, Hauguel‐Moreau M, Wallet T, Elegamandji B, Alamowitch S, Crozier S, Sabben C, Deltour S, et al. Supraventricular arrhythmia following patent foramen ovale percutaneous closure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:2315–2322. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2022.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hakeem A, Cilingiroglu M, Katramados A, Boudoulas KD, Iliescu C, Gundogdu B, Marmagkiolis K. Transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke: quantitative synthesis of pooled randomized trial data. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:1153–1160. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abo‐Salem E, Chaitman B, Helmy T, Boakye EA, Alkhawam H, Lim M. Patent foramen ovale closure versus medical therapy in cases with cryptogenic stroke, meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol. 2018;265:578–585. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-8750-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vidale S, Russo F, Campana C, Agostoni E. Patent foramen ovale closure versus medical therapy in cryptogenic strokes and transient ischemic attacks: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Angiology. 2019;70:325–331. doi: 10.1177/0003319718802635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agasthi P, Kolla KR, Yerasi C, Tullah S, Pulivarthi VS, Louka B, Arsanjani R, Yang EH, Mookadam F, Fortuin FD. Are we there yet with patent foramen ovale closure for secondary prevention in cryptogenic stroke? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized trials. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119828261. doi: 10.1177/2050312119828261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kheiri B, Abdalla A, Osman M, Ahmed S, Hassan M, Bachuwa G. Patent foramen ovale closure versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke: an updated meta‐analysis of all randomized clinical trials. Cardiol J. 2019;26:47–55. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, Alberts MJ, Chaturvedi S, Feldmann E, Hatsukami TS, Higashida RT, Johnston SC, Kidwell CS, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40:2276–2293. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.108.192218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.110.009449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61602-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta V, Yesilbursa D, Huang WY, Aggarwal K, Gupta V, Gomez C, Patel V, Miller AP, Nanda NC. Patent foramen ovale in a large population of ischemic stroke patients: diagnosis, age distribution, gender, and race. Echocardiography. 2008;25:217–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verbraecken J, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W, Van Gaal L. Body surface area in normal‐weight, overweight, and obese adults. A comparison study. Metabolism. 2006;55:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leppert MH, Burke JF, Lisabeth LD, Madsen TE, Kleindorfer DO, Sillau S, Schwamm LH, Daugherty SL, Bradley CJ, Ho PM, et al. Systematic review of sex differences in ischemic strokes among young adults: are young women disproportionately at risk? Stroke. 2022;53:319–327. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.121.037117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jeong SM, Jeon KH, Jung W, Yoo JE, Yoo J, Han K, Kim JY, Lee DY, Lee YB, Shin DW. Association of reproductive factors with cardiovascular disease risk in premenopausal women: nationwide population‐based cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30:264–273. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwac265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohya Y, Matsuo R, Sato N, Irie F, Nakamura K, Wakisaka Y, Ago T, Kamouchi M, Kitazono T. Causes of ischemic stroke in young adults versus non‐young adults: a multicenter hospital‐based observational study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0268481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kent DM, Ruthazer R, Weimar C, Mas JL, Serena J, Homma S, Di Angelantonio E, Di Tullio MR, Lutz JS, Elkind MS, et al. An index to identify stroke‐related vs incidental patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic stroke. Neurology. 2013;81:619–625. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a08d59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kent DM, Saver JL, Kasner SE, Nelson J, Carroll JD, Chatellier G, Derumeaux G, Furlan AJ, Herrmann HC, Juni P, et al. Heterogeneity of treatment effects in an analysis of pooled individual patient data from randomized trials of device closure of patent foramen ovale after stroke. JAMA. 2021;326:2277–2286. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.20956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lebedeva ER. Sex and age differences in migraine treatment and management strategies. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2022;164:309–347. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2022.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rossi MF, Tumminello A, Marconi M, Gualano MR, Santoro PE, Malorni W, Moscato U. Sex and gender differences in migraines: a narrative review. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:5729–5734. doi: 10.1007/s10072-022-06178-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang B, Li D, Song A, Ren Q, Cai S, Wang P, Tan W, Zhang G, Guo J. Characteristics of patent foramen ovale: analysis from a single center. Cardiol Res Pract. 2022;2022:5430598. doi: 10.1155/2022/5430598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kheiri B, Abdalla A, Osman M, Ahmed S, Hassan M, Bachuwa G, Bhatt DL. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen Ovale in migraine: a meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:816–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.01.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu M, Amarilla Vallejo A, Cantalapiedra Calvete C, Rudd A, Wolfe C, O'Connell MDL, Douiri A. Stroke outcomes in women: a population‐based cohort study. Stroke. 2022;53:3072–3081. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.121.037829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li L, Schulz UG, Kuker W, Rothwell PM. Age‐specific association of migraine with cryptogenic TIA and stroke: population‐based study. Neurology. 2015;85:1444–1451. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tietjen GE. Migraine as a systemic vasculopathy. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:987–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01937.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Putaala J, Martinez‐Majander N, Saeed S, Yesilot N, Jäkälä P, Nerg O, Tsivgoulis G, Numminen H, Gordin D, von Sarnowski B, et al. Searching for Explanations for Cryptogenic Stroke in the Young: Revealing the Triggers, Causes, and Outcome (SECRETO): rationale and design. Eur Stroke J. 2017;2:116–125. doi: 10.1177/2396987317703210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patti G, Pelliccia F, Gaudio C, Greco C. Meta‐analysis of net long‐term benefit of different therapeutic strategies in patients with cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:837–843. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.12.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kalmanti L, Lindhoff‐Last E. Bleeding issues in women under oral anticoagulation. Hamostaseologie. 2022;42:337–347. doi: 10.1055/a-1891-8187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Becker DM, Segal J, Vaidya D, Yanek LR, Herrera‐Galeano JE, Bray PF, Moy TF, Becker LC, Faraday N. Sex differences in platelet reactivity and response to low‐dose aspirin therapy. JAMA. 2006;295:1420–1427. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maas A, Rosano G, Cifkova R, Chieffo A, van Dijken D, Hamoda H, Kunadian V, Laan E, Lambrinoudaki I, Maclaran K, et al. Cardiovascular health after menopause transition, pregnancy disorders, and other gynaecologic conditions: a consensus document from European cardiologists, gynaecologists, and endocrinologists. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:967–984. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]