Abstract

Background

Guideline‐based hypertension management is integral to the prevention of stroke. We examine trends in antihypertensive medications prescribed after stroke and assess how well a prescriber's blood pressure (BP) medication choice adheres to clinical practice guidelines (BP‐guideline adherence).

Methods and Results

The FSR (Florida Stroke Registry) uses statewide data prospectively collected for all acute stroke admissions. Based on established guidelines, we defined optimal BP‐guideline adherence using the following hierarchy of rules: (1) use of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker as first‐line antihypertensive among diabetics; (2) use of thiazide‐type diuretics or calcium channel blockers among Black patients; (3) use of beta blockers among patients with compelling cardiac indication; (4) use of thiazide, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker, or calcium channel blocker class as first line in all others; (5) beta blockers should be avoided as first line unless there is a compelling cardiac indication. A total of 372 254 cases from January 2010 to March 2020 are in the FSR with a diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack, or subarachnoid hemorrhage; 265 409 with complete data were included in the final analysis. Mean age was 70±14 years; 50% were women; and index stroke subtypes were 74% acute ischemic stroke, 11% intracerebral hemorrhage, 11% transient ischemic attack, and 4% subarachnoid hemorrhage. BP‐guideline adherence to each specific rule ranged from 48% to 74%, which is below quality standards of 80%, and was lower among Black patients (odds ratio, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.7–0.83]; P<0.001) and those with atrial fibrillation (odds ratio, 0.53 [95% CI, 0.50–0.56]; P<0.001) and diabetes (odds ratio, 0.65 [95% CI, 0.61–0.68]; P<0.001).

Conclusions

This large data set demonstrates consistently low rates of BP‐guideline adherence over 10 years. There is an opportunity for monitoring hypertensive management after stroke.

Keywords: blood pressure, disparities, ethnicity, Florida, hypertension, race, stroke

Subject Categories: Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, Intracranial Hemorrhage, Ischemic Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA), High Blood Pressure

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- FSR

Florida Stroke Registry

- GWTG‐S

Get With The Guidelines–Stroke

- JNC

Joint National Committee

- REGARDS

Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke

- SPRINT

Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

In this large, hospital‐based registry, we have demonstrated racial and ethnic disparities in blood pressure (BP)‐guideline adherence to antihypertensive guidelines‐based treatments on the basis of 5 poststroke BP‐guideline adherence rules.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Clinicians should carefully consider whether their patients' BP medications are consistent with clinical practice guidelines. In this study, BP‐guideline adherence remains low (48%–70%) with no significant improvement over the course of a decade; further, 50% of Black individuals do not receive BP‐guideline adherence first‐line medication options, and 20% of people may have received a beta blocker without a compelling cardiac indication.

The proposed BP‐guideline adherence rules are presented in a hierarchical algorithm, prioritizing the patient's medical comorbidities, making it easy for clinicians to follow, and potentially makes this clinical variability in the choice of medications easier to codify for quality measures and improve.

Hypertension is the single most important modifiable stroke risk factor, accounting for 36% of the population attributable stroke risk. 1 It is an independent and major driver of both primary and secondary stroke recurrence in the population, with known racial and ethnic differences in its rate of control and medication compliance. 2 , 3 , 4 Adequate control of blood pressure (BP) reduces the risk of stroke by 30%. 5 , 6 , 7 Several clinical trials 3 , 4 , 8 , 9 , 10 have revealed—and subsequent guidelines 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 have recommended—specific medications on the basis of compelling indications that not only optimizes BP control but also prioritizes death and morbidity benefits of specific agents. In the poststroke setting, the recommended first‐line antihypertensives are thiazide diuretics, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and with more targeted therapy made in consideration of a patient's medical comorbidities or the social constructs of race and ethnicity. 13 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Beta blockers are no longer considered first‐line therapy in the poststroke setting except in the case of a compelling cardiac indication. 13 , 16 , 20

The choice of antihypertensive medications based on the compelling indications for vascular comorbidities has been supported by clinical practice guidelines since the Sixth Joint National Commission on hypertension and affirmed by recent clinical practice guidelines. Currently, there are no poststroke quality measures that facilitate implementation of BP‐guideline adherence for secondary prevention of stroke. We examine the contemporary trends in choice of antihypertension medications following stroke and introduce a novel concept of BP‐guideline adherence to clinical practice guidelines. We hypothesized that if guideline recommendations are fully implemented, then BP‐guideline adherence would be >80% for each compelling indication. Further, we examined the impact of social determinants of health on BP‐guideline adherence rules and racial and ethnic variabilities.

Methods

Setting

The FSR (Florida Stroke Registry) is a statewide data repository that collects data from 168 voluntarily participating stroke hospitals that use the American Heart Association's Get With The Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG‐S) database. The FSR at its origins was a National Institutes of Health–funded grant 5U54NS081763 and received institutional approval from our local institutional review board (ID 20120987; CR00012124). It continues as a state‐funded quality improvement initiative supported by the Florida legislature, which prescribes that all stroke centers be stroke certified and submit deidentified data to the FSR. All consecutive patients with stroke are enrolled to avoid sampling bias, and informed consent is not obtained as only deidentified data are collected as part of the FSR. The FSR has previously demonstrated racial, ethnic, and sex disparities in acute stroke care, 21 , 22 and details of the FSR are previously described. 21 , 23 In brief, each FSR hospital has specialized abstractors who submit data on all stroke cases to the GWTG‐S form. Included in the standard GWTG‐S data collection system, the FSR also reports several questions regarding self‐reported race ethnicity such as Black Americans, White Americans (non‐Hispanic White, NHW), and Hispanic. The BP Medication Use Questionnaire allows collection of information regarding the number and class of antihypertensive medications prescribed. It includes specific fields to identify if no antihypertensives were prescribed or whether these medications were contraindicated.

Population

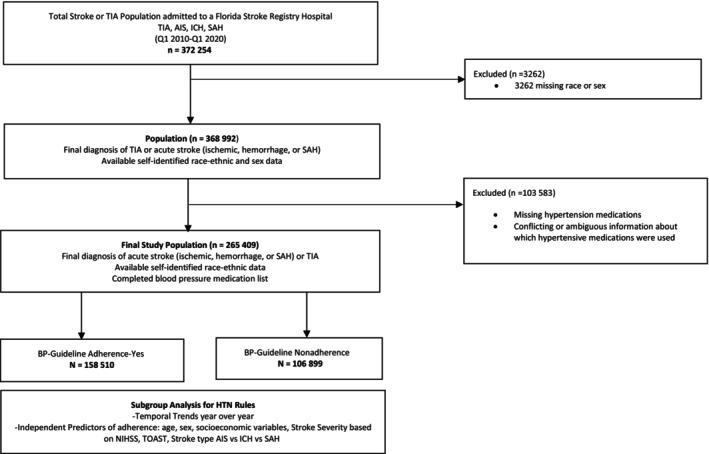

All patients admitted to a participating FSR hospital, with a discharge diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack, acute intracerebral hemorrhage, transient ischemic attack, or subarachnoid hemorrhage and with a completed BP Medication Use Questionnaire between January 2010 and April 2020 were included in this analysis. All stroke subtypes 24 are included: ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ischemic strokes are then further classified on the basis of the Trial of ORG in Acute Ischemic Stroke Classification. 25 For the decade analyzed, 121 hospitals from all the counties in Florida with 372 254 stroke admissions were voluntarily participating in the FSR. Inclusion criteria were as follows: final diagnosis of transient ischemic attack, acute stroke of either subtype, available race and ethnicity data, and a completed BP medications list. Diagnosis of hypertension for this study includes patients with an admission diagnosis of hypertension, antihypertensive medications included in the home medications list, BP >140/90, hypertension included in the final International Classification of Diseases (ICD) discharge diagnosis codes, or discharge on antihypertensive medications. Concurrent chronic medical illnesses were defined on the basis of an admission diagnosis of a preexisting medical condition (eg, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation), or there was a documented new diagnosis of either of these conditions at discharge that could specifically be selected in the forms. New‐onset diabetes, that is, hospital‐based diagnosis of diabetes, is based on glycated hemoglobin >7% or the patient started on antihyperglycemic agents and is coded in the discharge ICD diagnosis. New‐onset atrial fibrillation is based on hospital‐based telemetry monitoring or as included in the discharge diagnosis codes. Smoking habits and excessive alcohol use also have discrete forms for collection based on the admission or discharge documentation by the treating physician. Patients with incomplete records or records containing conflicting information regarding antihypertensive medications prescribed were excluded (n=103 583) from the final analysis. Examples of conflicting information included the simultaneous selection of both “none” OR “medications contraindicated” AND “a specific antihypertensive medication” for the same patient in the same form. Please see the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

AIS indicates acute ischemic stroke; BP, blood pressure; HTN, hypertension; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; TIA, transient ischemic attack; and TOAST, Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

Definition of BP‐Guideline Adherence

In 1997, the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee (JNC) on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure 15 established recommendations for first‐line therapy based on race and ethnicity and medical comorbidities. The term “compelling medical indication” was first introduced in the JNC Sixth Report on the basis of multiple randomized trials that demonstrated benefit of ≥1 classes of drugs on the basis of patients' medical comorbidities. While stroke was not specifically listed as a compelling indication, the included meta‐analysis demonstrated that high‐dose diuretics and ACEIs were preferred for stroke prevention, while beta blockers were potentially harmful. The recommendations for stroke as a compelling indication was included in the JNC's Seventh guideline and have been reaffirmed with subsequent iterations of the JNC Eighth Report 12 , 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 19 and the 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines 13 with the recommendation for BP medication choice (BP‐guideline adherence) after stroke specifically incorporated. Based on this body of knowledge, we designed 5 simple hierarchical rules that can be used to determine BP‐guideline adherence:

Use of an ACEI or ARB as first line in patients with diabetes irrespective of race. 15

Use of thiazide‐type diuretics or calcium channel blockers among Black patients, as they had a superior response to treatment 26 and morbidity and mortality benefits. 15

Use of beta blockers among patients with coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, or other compelling cardiac indication irrespective of race ethnic origins 15 as it conferred a mortality benefit.

Use of thiazide, ACEI/ARB, or calcium channel blocker class for all others not included in rules 1 through 3 above. 15

Beta blockers should be avoided as first line unless there is a compelling cardiac indication.

This study is consistent with the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Data Statement, which is extended from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting checklist (Table S1). We collected baseline demographic information, insurance status, past medical history, and other variables of interest, including final discharge diagnosis related to stroke including transient ischemic attack, acute ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, or nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage; pathogenesis of acute ischemic stroke based on the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment classification 25 ; medication list before stroke admission and at discharge; antihypertensive medications at discharge; discharge disposition; and modified Rankin scale score at discharge.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were provided for each variable. Chi‐squared and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to determine differences in demographic and stroke characteristics.

Univariate statistics were summarized using numbers and percentages for categorical variables; means and SDs were used for continuous variables. In this large data set, alpha was set at 0.001; and significance was declared if P values were <0.001 and there was a >2% difference between groups for statistical significance. Because the sample size is large, a very small and clinically insignificant difference can still reach statistical significance, even with a strict P value cutoff. For this reason, the 2% cutoff was included to identify variables to be included in the multivariable analysis to make the models parsimonious, improve efficiency, focus on the most clinically impactful predictors, and maintain the stability of the confidence bounds. As sensitivity analyses, we constructed additional models, one in which a more restrictive model of ≥5% difference is used, another with a more liberal 1% difference cutoff, and a final model with no such cutoff at all was used as an alternative criterion.

We conducted multivariable analysis with generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to account for clustering effects within each hospital addressing hospital‐level variations in outcomes and comparing BP‐guideline adherence and BP guideline nonadherence and determine whether independent associations were present. In this generalized estimating equation model, we controlled for race and ethnicity, insurance status, medical comorbidity, age, and sex as primary predictors of adherence on the basis of statistical significance as defined above with BP‐guideline adherence was designated the dependent variable. Odds ratios and 95% CIs were calculated to determine differences in BP‐guideline adherence versus nonadherence.

Most variables had <5% missing values. Those cases with missing data were not different from the overall cohort. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The statistical team and first author had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the data integrity and data analysis.

Data Availability

As FSR uses data from American Heart Association's GWTG‐S, data‐sharing agreements require an application process for other researchers to access data. Researchers can submit proposals at www.heart.org/qualityresearch to be considered by the GWTG‐S steering committees.

Analytic requests of the data are subject to approval by the FSR publication committee, and aggregate, blinded data may be shared by the corresponding author upon written request from any qualified investigator.

Results

There were 265 409 cases included in the final analysis: mean age, 70.6 +/−14.7 years; 50.3% women; non‐Hispanic White patients; 68.6%; Black patients, 17.6%; and Hispanic patients, 13.8%. The index admitting event consisted of 74% acute ischemic stroke, 11% transient ischemic attack, 11% intracerebral hemorrhage, and 4% subarachnoid hemorrhage. Antihypertensive medications at discharge were prescribed in 70% of cases; 19% had a contraindication, and 10% were prescribed lifestyle modifications. Table 1 summarizes the study population demographics and characteristics based on BP‐guideline adherence versus nonadherence.

Table 1.

Study Population Demographics With Characteristics: BP‐Guideline Nonadherent vs BP‐Guideline Adherent Cohorts

| Variables | Overall n=265 409 | BP‐guideline nonadherent n=106 899 | BP‐guideline adherent n=158 510 | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 70.6 (14.7) | 70.7 (15.3) | 70.6 (14.3) | 0.237 |

| Sex, female, % | 50.3 | 50.0 | 50.5 | 0.030 |

| Race or ethnicity, % | ||||

| White | 68.6 | 66.3 | 70.1 | <0.001 |

| Black | 17.6 | 20.7 | 15.5 | |

| Hispanic | 13.8 | 13.0 | 14.36 | |

| Index event type,* % | ||||

| Transient ischemic attack | 10.9 | 10.8 | 11 | 0.022 |

| Acute ischemic stroke | 73.7 | 73.6 | 73.8 | |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 11.3 | 11.6 | 11.1 | |

| Acute ischemic stroke pathogenesis (TOAST criteria), % | ||||

| Cardioembolism | 7.5 | 8.2 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Cryptogenic | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.8 | |

| Large‐vessel atherosclerosis | 5.7 | 5.9 | 6.9 | |

| Small‐vessel occlusion | 6.4 | 5.6 | 6.9 | |

| Stroke of other determined | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1 | |

| Unknown stroke pathogenesis subtype | 70.5 | 70.4 | 70.6 | |

| Insurance, % | ||||

| Private | 38.2 | 37.5 | 38.6 | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 44.2 | 45 | 43.5 | |

| Medicaid | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 | |

| Self‐pay | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.9 | |

| Diabetes, % | 31.8 | 37.6 | 27.8 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter, % | 18.3 | 23.5 | 14.9 | <0.001 |

| Stroke or TIA before index event, % | 29.4 | 30.1 | 28.9 | <0.001 |

| Discharged home | 48.4 | 44.2 | 51.3 | <0.001 |

| mRS score at discharge | ||||

| mRS 0–2 | 43.4 | 39.7 | 45.8 | <0.001 |

| mRS 3–5 | 51.3 | 50.9 | 51.5 | |

| mRS 6 | 5.4 | 9.3 | 2.7 |

Diagnosis of diabetes and atrial fibrillation based on discharge ICD diagnostic codes.

BP‐guideline adherent: percentage of patients who were prescribed guideline‐based therapy as determined by 5 simple guideline‐derived rules.

Acute ischemic stroke subtypes are based on the included discharge diagnosis codes. The stroke pathogenesis for acute ischemic stroke based on TOAST is a prespecified field in the data. The Unknown stroke pathogenesis subtype was specifically selected for the data set and does not represent missing data. BP indicates blood pressure; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; mRS, modified Rankin scale; TIA, transient ischemic attack; and TOAST, Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

Index event type refers to the hospitalization event that resulted in the case inclusion in the Florida Stroke Registry, which is based on the discharge ICD diagnosis codes.

Table 2 outlines contemporary antihypertensive medications prescribed in our cohort, with 42% of patients receiving combination therapy and 39% receiving 1 or another monotherapy. The most prescribed antihypertensive medication in the poststroke setting was a beta blocker (38%) either alone or in combination (also see Table 2). Guideline‐preferred adherence combination following stroke—ACEIs and diuretics—was used in only 3% of cases. Diuretic monotherapy was prescribed in 1% of cases.

Table 2.

Frequency of Antihypertensive Medications Prescribed After Stroke in the Florida Stroke Registry

| Medication | Frequency, % | Cumulative, % |

|---|---|---|

| ACEI only | 8.91 | 8.91 |

| ARB only | 2.49 | 11.4 |

| Beta blocker only | 9.24 | 20.64 |

| CCB only | 5.19 | 25.83 |

| Combination therapy | 41.73 | 67.56 |

| Contraindicated | 19.09 | 86.65 |

| Diuretics only | 1.25 | 87.9 |

| None prescribed | 10.89 | 98.79 |

| Other only | 1.21 | 100 |

Medications are listed in alphabetical order by their group classifications. ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta blockers; and CCB, calcium channel blockers. Other only: All other classes of antihypertensive medication such as vasodilators; combination therapy: >1 class of antihypertensive medications prescribed.

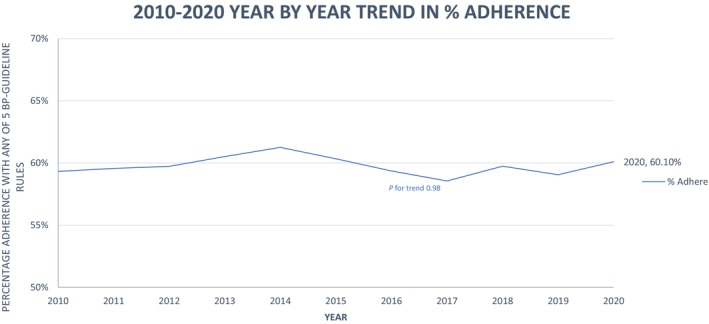

Overall adherence to each specific poststroke BP‐guideline adherence rule was low, ranging from 48% to 74%, with an overall adherence to any of the 5 BP‐guideline adherence rules being only 60%. Table 3 describes each BP‐guideline adherence rule, its supporting evidence, and the results of this cohort relative to the benchmark threshold of 80% adherence. We selected a threshold of 80% as a more lenient goal than the GWTG recommended 85% for quality indicators. 27 , 28 This trend did not vary by year from 2010 to 2020 (see Figure 2) and continued to be consistently low over the past decade.

Table 3.

Evidence for BP‐Guideline Adherence Rules and Percentage Adherence to Each Rule

| BP‐guideline adherence rules* | LOE | Hypertension guideline | 2006 Secondary Stroke Prevention Guideline | 2011 Secondary Stroke Prevention Guideline | 2014 Secondary Stroke Prevention Guideline | Threshold, % | BP‐guideline adherence, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use ACEI or ARB in diabetes | A |

JNC 6 – ISH 1997–2020 |

|

|

|

80 | 53.4 |

| Black patient use of diuretic or CCB | A |

JNC 7 – ISH 2003–2020 |

Silent Endorses JNC7 |

Silent Endorses 2011 Primary Stroke |

Silent Endorses 2011 Primary Stroke |

80 | 48.5 |

| Use of diuretic, ACEI/ARB or CCB | A |

JNC 7 – ISH 2003–2020 |

|

|

|

80 | 74.4 |

| BB in compelling cardiac indication | A |

JNC 6 – ISH 1997–2020 |

Silent Endorses JNC7 |

|

|

80 | 52 |

| Failed to avoid BB without compelling indication, % | A |

JNC 6 – ISH 1997–2020 |

Silent Endorses JNC7 |

Silent Endorses 2011 Primary Stroke |

Silent Endorses 2011 Primary Stroke |

<5 | 20 |

| Any 1 of 5 rules combined | A | ALL |

|

|

|

80 | 59.7 |

BP‐guideline adherence rules are derived from the 2020 ISH Global Hypertension Guidelines. We reviewed all prior guidelines to identify the first appearance of the rule to ensure it was in clinical practice for the years assessed. ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; ISH, International Society of Hypertension; and JNC, Joint National Commission on Hypertension.

This is different from compliance as it focused on the prescriber's choice of antihypertensive agents and how that matches with existing guidelines rather than the patient's ability to consistently take the medication.

Figure 2. Trends in adherence to any of the 5 BP‐guideline adherence rules over the course of 10 years.

BP indicates blood pressure.

BP‐guideline nonadherence was most prevalent among the following demographics: Black race (20.7% versus 15.5% non‐Hispanic White; P<0.001); patients with diabetes (37.5% versus 27.8% patients with diabetes; P<0.001); and atrial fibrillation (23.5% versus 14.9% no atrial fibrillation; P<0.001). Hispanic individuals in the FSR were more likely to be BP‐guideline adherent (14% versus 13% nonadherent; P<0.001), but this did not reach the predefined significance threshold. One in 5 patients were prescribed a beta blocker without a compelling cardiac indication and were considered BP‐guideline nonadherent. ACEIs/ARBs were not used as first line in 46.6% of patients with diabetes, and 47% of cases with a compelling cardiac indication were not prescribed a beta blocker. Among Black cases, 51.5% were not prescribed a diuretic or calcium channel blocker as first‐line therapy.

Ischemic stroke subtypes were not associated with an increased likelihood of BP‐guideline adherence. When statistically significant variables are further assessed in a general estimating equation model that accounted for hospital‐based clustering, the effect estimates remained essentially unchanged in the full model versus the 1% models. In the more restrictive 5% models, several clinically significant variables are removed and therefore this model was not used in the final analysis. Table 4 presents the results of the generalized estimating equation models with significant P value plus 2% model as the primary analytic model because efficiency is improved, and the CIs are narrow. For example, in a generalized estimating equation model that controlled for age, sex, race, insurance, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation, the effect estimates for Hispanic ethnicity (odds ratio, 1.05 [95% CI, 1.02–1.09]; P<0.002) became stronger and the statistical significance is better appreciated. Patients with lower odds of being BP‐guideline adherent included Black patients (odds ratio, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.7–0.83]; P<0.001), patients with atrial fibrillation (odds ratio, 0.53 [95% CI, 0.50–0.56]; P<0.001), and patients with diabetes (odds ratio, 0.65 [95% CI, 0.61–0.68]; P<0.001).

Table 4.

GEE Model Predication: Effect of Variables on BP‐Guideline Adherence

| Category | Model 1 primary analysis includes all variables with a positive P value and 2% threshold | Model 2 includes all variables with a positive P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | OR | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | P value | OR | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | |

| Age | 0.0002 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.0074 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 |

| Female | 0.43 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | <0.0001 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 |

| Black | <0.0001 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.74 | <0.0001 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.54 |

| Hispanic | 0.002 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 0.0853 | 1.14 | 0.98 | 1.33 |

| Medicare | 0.49 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.02 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.82 |

| Medicaid | 0.02 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 0.4338 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.04 |

| Self‐insurance | 0.04 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 0.0001 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.82 |

| Diabetes | <0.0001 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.68 | <0.0001 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.63 |

| Atrial fibrillation | <0.0001 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.56 | <0.0001 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.47 |

| Prestroke mRS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0.0002 | 1.23 | 1.10 | 1.36 |

| TIA or stroke before this index event | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | <0.0001 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.14 |

Interpretation examples: Black individuals are 31% less likely to receive BP‐guideline adherent therapy with a P<0.0001, and patients with Medicaid insurance are 5% more likely to receive BP‐guideline adherent therapies.

GEE indicates multivariable generalized estimating equations to account for clustered within hospitals; mRS, modified Rankin score; OR, odds ratio; and TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Discussion

A prescriber's ability to choose medications as recommended by antihypertensive guidelines is influenced by multiple factors. Our study highlights these real‐world challenges. With new data emerging 29 about the impact of drug class on hypertension control, our study is novel and timely, assessing current practice in an acute stroke cohort and creating a paradigm for monitoring and quality improvement of these data. Our data show that BP‐guideline adherence remained low (48%–70%) over the course of a decade despite level A evidence, strong recommendations from multiple clinical practice guidelines, and several years to facilitate adoption. These data suggest that current prescribing practices are unlikely to change unless specific antihypertensive prescribing quality measures for monitoring clinical practice are implemented or a formal way to track and trend BP‐guideline adherence is developed, as proposed by this study.

Principal Findings

This study goes beyond the question of whether antihypertensive medications are prescribed and specifically explores if the prescribed medications meet the evidence‐based guidelines. Guideline‐based recommendations are often crafted around benefits based on each patient's medical comorbidities and outcome data from morbidity and mortality data. By describing, testing, and standardizing these simple rules applied in a stepwise algorithm, other large data sets or quality indicators can follow this paradigm to evaluate on a more granular level this important question of BP‐guideline adherence. There has been debate about whether the choice of antihypertensive medications matters, but rather only that the BP goal is achieved. There are now new data from SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) 29 demonstrating that drug class influences outcomes following stroke, with protective effects seen with thiazide‐type diuretics and ARBs but a potential for harm with beta blockers in this setting.

We demonstrate that applying these BP‐guideline adherence rules is feasible and could be used as new quality measures to improve compliance with poststroke guideline recommendations, for secondary stroke prevention. Deciding when to start antihypertensive medications and tailoring the choice of antihypertensive medication during hospitalization is often difficult. In addition, there may be insufficient time during acute hospitalization to modify a regimen that may have been appropriate in the acute setting or during intensive care.

There is significant evidence for hypertension management in stroke. McGurgan et al 30 provides a critical review of the plethora of evidence and highlight the challenges of adherence to guidelines. Our study offers innovative guideline‐based rules as an easy tool for clinicians to consider when prescribing poststroke antihypertensive medications. The proposed BP‐guideline adherence rules are presented in a hierarchical algorithm, prioritizing the patient's medical comorbidities, making it easy for clinicians to follow, and potentially makes this clinical variability in the choice of medications easier to codify for quality measures.

Disparities

We found that Black individuals had lower odds of having the BP‐guideline adherence to guidelines‐based BP medications after stroke, with 1 in 2 patients not prescribed guideline‐based first‐choice agents. This is consistent with prior work 17 , 23 , 26 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 on racial and ethnic disparities in hypertension and stroke management such as the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. 31 This disparity persisted even after controlling for insurance type, age, and other medical comorbidities and not related to patient compliance to medication but rather a prescriber's choice of antihypertensive medication after a stroke. The reason for this is likely multifactorial and cannot be gleaned from this study. The data regarding optimal choice of antihypertensive medication among Black patients 13 , 31 , 34 , 35 and specifically diuretics as first‐line therapy in Black patients are not readily accepted. 36 Some clinicians cite the low rates (4%–13%) of Black patient enrollment in clinical trials. Additionally, there may be some distrust of the antihypertensive guidelines as they relate to recommendations of antihypertensive based soley on a patients race which is a social construct or distrust based on the debate surrounding the Eighth JNC guidelines. 16 , 19 Whether or not this contributes to this disparity in BP‐guideline adherence cannot be assessed in this observational study but highlights an area for future research. For example, should the social construct of race really influence the choice of antihypertensive medication? Should the antihypertensive guidelines be updated to address this area?

It is noteworthy that beta blockers were the most prescribed antihypertensive medications, despite evidence of potential for harm without the strong benefit of secondary stroke prevention. 18 , 37 , 38 The reason for this preference in using beta blockers following stroke cannot be gleaned from this observational analysis. Additionally, the guideline‐preferred combination of antihypertensive medications—ACEIs and diuretics—is used very infrequently. By using the BP‐guideline adherence rules as quality measures, tracking and assessing these measures prospectively, we may better delineate the cause of this variability with BP‐guideline adherence, and this presents an opportunity for future research or quality interventions.

Strengthens and Limitations

An important strength of this analysis is the large cohort sample size with <5% missingness. Those cases with incomplete data were not demographically different from the final cohort. The data could be generalizable outside of Florida due to the large sample size from many institutions and large geographic area with a diverse cohort of patients. Our study has a diverse cohort, with 17% Black patients and 19% Hispanic patients, which is powerful for assessing disparities in racial and ethnic associations. The longevity of the FSR provides an unparalleled view of poststroke antihypertensive prescribing practices over the course of 10 years.

One possible explanation for our findings is that prescribers may choose not to start BP medications during the acute admission because of risk of hypotension and worsening infarct in the acute setting primarily among patients with intracranial stenosis. However, this is unlikely to be a primary driver of prescribing practices as there is no difference in BP‐guideline adherence among patients with transient ischemic attack or based on acute ischemic stroke pathogenesis subtype. Another possible explanation is that hospitalizations after stroke may have a short length of stay, so home medications or medications from the emergency department or intensive care unit are continued until discharge.

A limitation of our deidentified and aggregated, hospital‐based data set is that we are unable to discern readmission rates, long‐term BP control, recent changes in baseline home medications, duration of treatment, recurrent stroke, or long‐term outcomes for these cases. Moreover, we could not assess whether medication use was influenced by in‐hospital events or medication adverse effects; for example, a myocardial infarct during hospitalization would lead to the use of a beta blocker, or renal injury with an ACEI would lead to discontinuation of that medication before discharge. In this large cohort of patients, the ischemic stroke subtype had larger‐than‐expected unclassified stroke types, which may reflect incomplete stroke mechanism evaluations in the real‐world setting. However, in this large cohort, these potential confounding cases are likely to be the exception rather than the norm.

Perspectives

In this large, hospital‐based Florida Stroke Registry, we have demonstrated racial and ethnic disparities in BP‐guideline adherence to antihypertensive guideline‐based treatments in real‐world acute stroke cases. There is suboptimal adherence to hypertension management guidelines, with at least 30% to 40% of cases not guideline adherent. This represents a quality improvement opportunity for future research into limitations of guideline implementation, future quality improvement projects, and educational interventions to address this public health disparity and can inform local policy implementation. Future studies will assess the impact of BP‐guideline adherence of stroke outcomes, such as 30‐day or 90‐day stroke readmission and stroke recurrence, and create interventions to improve evidence‐based antihypertensive management. Future studies should also assess the impact of the SARS‐COV‐2 pandemic on BP‐guideline adherence, with a focus on racial and ethnic disparities.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders through the Stroke Prevention and Intervention Research Program cooperative grant (Grant Number: U54NS081763) and the Florida Department of Health. This study is funded by the state of Florida Department of Health; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities: R01MD012467.

Disclosures

Dr Sacco was the recipient and the primary investigator of the Stroke Prevention/Intervention Research Program cooperative grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders (Grant Number: U54NS081763) and the recipient of the FSR Grant (COHAN‐ A1 R2). Dr Rundek is the recipient of the women's supplement from the National Institutes of Health, Office of Research on Women's Health, and receives salary support from the Stroke Prevention/Intervention Research Program cooperative grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders (Grant Number: U54NS081763‐01S1). Dr Romano receives research salary support from the FSR COHAN‐A1 R2 contract. Dr Asdaghi receives research salary support from the FSR COHAN‐A1 R2 contract. Dr Koch receives research salary support from the FSR COHAN‐A1 R2 contract. Dr Gordon Perue receives research salary support from the FSR COHAN‐A1 R2 contract. Dr Alkhachroum is supported by an institutional KL2 Career Development Award from the Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant Number: UL1TR002736). The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the leadership and support of the FSR (Florida Stroke Registry), particularly the FSR's executive and publication committees, as well as each of the participating FSR hospitals and their staff. Author contributions: Dr Perue: study concept, design, original manuscript draft, manuscript revision, and final approval; H. Ying: statistical analysis, manuscript revision, and final approval; A. Bustillo: statistical analysis, manuscript revision, and final approval; L. Zhou: statistical analysis, manuscript revision, and final approval; Dr Gutierrez: manuscript revision and final approval; K. Wang: statistical analysis; H.E. Gardener: statistical analysis, manuscript revision, and final approval; D. Foster: manuscript revision and final approval; Dr Rose: manuscript revision and final approval; Dr Dong: manuscript revision and final approval; Dr Rundek: manuscript revision and final approval; Dr Romano: manuscript revision and final approval; Dr Sacco: manuscript revision and final approval; Dr Asdaghi: study concept, design, manuscript revision, and final approval; Dr Koch: study concept, design, manuscript revision, and final approval. Additional information: Coauthor Ralph Sacco, MD died January 17, 2023.

N. Asdaghi and S. Koch contributed equally to this article as co‐senior authors.

Preprint posted on MedRxiv February 16, 2023. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.23286003.

This manuscript was sent to Luciano A. Sposato, MD, MBA, FRCPC, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.030272

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

References

- 1. O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao‐Melacini P, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Pais P, McQueen MJ, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case‐control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112–123. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60834-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katsanos AH, Filippatou A, Manios E, Deftereos S, Parissis J, Frogoudaki A, Vrettou AR, Ikonomidis I, Pikilidou M, Kargiotis O, et al. Blood pressure reduction and secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review and metaregression analysis of randomized clinical trials. Hypertension. 2017;69:171–179. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.116.08485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair‐Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990‐2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anti‐hypertensive VACSGo, Agents . Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA. 1967;202:1028–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.1967.03130240070013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlöf B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, Ménard J, Rahn KH, Wedel H, Westerling S. Effects of intensive blood‐pressure lowering and low‐dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7160.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, Chireau MV, Fedder WN, Furie KL, Howard VJ, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Piña IL, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:1545–1588. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000442009.06663.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, Khan NA, Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Ramirez A, Schlaich M, Stergiou GS, Tomaszewski M, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334–1357. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.15026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whitworth JA, Chalmers J. World health organisation‐international society of hypertension (WHO/ISH) hypertension guidelines. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2004;26:747–752. doi: 10.1081/ceh-200032152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The sixth report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440420033005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison‐Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, et al. 2014 evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Flack JM, Sica DA, Bakris G, Brown AL, Ferdinand KC, Grimm RH Jr, Hall WD, Jones WE, Kountz DS, Lea JP, et al. Management of high blood pressure in Blacks: an update of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks consensus statement. Hypertension. 2010;56:780–800. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.152892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–1324. doi: 10.1161/hyp.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wright JT Jr, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:499–503. doi: 10.7326/m13-2981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, Wedel H, Beevers DG, Caulfield M, Collins R, Kjeldsen SE, Kristinsson A, McInnes GT, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial‐Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT‐BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67185-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sacco RL, Gardener H, Wang K, Dong C, Ciliberti‐Vargas MA, Gutierrez CM, Asdaghi N, Burgin WS, Carrasquillo O, Garcia‐Rivera EJ, et al. Racial‐ethnic disparities in acute stroke Care in the Florida‐Puerto Rico Collaboration to reduce stroke disparities study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004073. doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.004073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Asdaghi N, Romano JG, Wang K, Ciliberti‐Vargas MA, Koch S, Gardener H, Dong C, Rose DZ, Waddy SP, Robichaux M, et al. Sex disparities in ischemic stroke care: FL‐PR CReSD study (Florida‐Puerto Rico collaboration to reduce stroke disparities). Stroke. 2016;47:2618–2626. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.116.013059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gardener H, Leifheit EC, Lichtman JH, Wang K, Wang Y, Gutierrez CM, Ciliberti‐Vargas MA, Dong C, Robichaux M, Romano JG, et al. Race‐ethnic disparities in 30‐day readmission after stroke among Medicare beneficiaries in the Florida stroke registry. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:104399. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, Donnan GA, Hennerici MG. Classification of stroke subtypes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:493–501. doi: 10.1159/000210432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE 3rd. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beckie TM. Ethnic and racial disparities in hypertension management among women. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:278–286. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song S, Fonarow GC, Olson DM, Liang L, Schulte PJ, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, Schwamm LH, et al. Association of get with the guidelines‐stroke program participation and clinical outcomes for medicare beneficiaries with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:1294–1302. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.115.011874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smaha LA. The American Heart Association get with the guidelines program. Am Heart J. 2004;148:S46–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DeCarolis DD, Gravely A, Olney CM, Ishani A. Impact of antihypertensive drug class on outcomes in the SPRINT. Hypertension. 2022;79:1112–1121. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.121.18369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McGurgan IJ, Kelly PJ, Turan TN, Rothwell PM. Long‐term secondary prevention: management of blood pressure after a transient ischemic attack or stroke. Stroke. 2022;53:1085–1103. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.121.035851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Akinyelure OP, Jaeger BC, Moore TL, Hubbard D, Oparil S, Howard VJ, Howard G, Buie JN, Magwood GS, Adams RJ, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control following stroke: the REGARDS study. Stroke. 2021;52:3944–3952. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.120.033108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aggarwal R, Chiu N, Wadhera RK, Moran AE, Raber I, Shen C, Yeh RW, Kazi DS. Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in the United States, 2013 to 2018. Hypertension. 2021;78:1719–1726. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.121.17570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carson AP, Howard G, Burke GL, Shea S, Levitan EB, Muntner P. Ethnic differences in hypertension incidence among middle‐aged and older adults: the multi‐ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2011;57:1101–1107. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.168005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ferdinand KC, Yadav K, Nasser SA, Clayton‐Jeter HD, Lewin J, Cryer DR, Senatore FF. Disparities in hypertension and cardiovascular disease in blacks: the critical role of medication adherence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:1015–1024. doi: 10.1111/jch.13089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koch S, Elkind MS, Testai FD, Brown WM, Martini S, Sheth KN, Chong JY, Osborne J, Moomaw CJ, Langefeld CD, et al. Racial‐ethnic disparities in acute blood pressure after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2016;87:786–791. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shepherd S. Commentary: First Do no Harm. Let's Eradicate the Inherent Racism in Medicine. Chicago: Chicago Tribune; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Program. NHBPE . The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan WV, Pearson TA, Bennett GC, Cushman WC, Gaziano TA, Gorman PN, Handler J, Krumholz HM, Kushner RF, MacKenzie TD, et al. ACC/AHA special report: clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: a summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI implementation science work group: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e122–e137. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

As FSR uses data from American Heart Association's GWTG‐S, data‐sharing agreements require an application process for other researchers to access data. Researchers can submit proposals at www.heart.org/qualityresearch to be considered by the GWTG‐S steering committees.

Analytic requests of the data are subject to approval by the FSR publication committee, and aggregate, blinded data may be shared by the corresponding author upon written request from any qualified investigator.