Abstract

Background

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is the most prevalent monogenic cerebral small‐vessel disease. Phenotype variability in CADASIL suggests the possible role of genetic modifiers. We aimed to investigate the contributions of the APOE genotype and Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 3 (NOTCH3) variant position to cognitive impairment associated with CADASIL.

Methods and Results

Patients with the cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variant were enrolled in a cross‐sectional study, including the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE), brain magnetic resonance imaging, and APOE genotyping. Cognitive impairment was defined as an MMSE score <24. The associations between the MMSE score and genetic factors were assessed using linear regression models. Bayesian adjustment for confounding was used to identify clinical confounders. A total of 246 individuals were enrolled, among whom 210 (85%) harbored the p.R544C variant, 96 (39%) had cognitive impairment, and 150 (61%) had a history of stroke. The APOE ɛ2 allele was associated with a lower MMSE score (adjusted B, −4.090 [95% CI, −6.708 to −1.473]; P=0.023), whereas the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant was associated with a higher MMSE score (adjusted B, 2.854 [95% CI, 0.603–5.105]; P=0.0132) after adjustment for age, education, and history of ischemic stroke. Mediation analysis suggests that the associations between the APOE ɛ2 allele and MMSE score and between the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant and MMSE score are mediated by mesial temporal atrophy and white matter hyperintensity, respectively.

Conclusions

APOE genotype may modify cognitive impairment in CADASIL, whereby individuals carrying the APOE ɛ2 allele may present a more severe cognitive impairment.

Keywords: APOE, CADASIL, cerebral small‐vessel disease, NOTCH3, vascular cognitive impairment

Subject Categories: CADASIL, Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, Cognitive Impairment

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BAC

Bayesian adjustment for confounding

- CADASIL

cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

- DWM

deep white matter

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor–like repeat

- MTA

mesial temporal atrophy

- SVD

small‐vessel disease

- WMH

white matter hyperintensity

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

In this cross‐sectional analysis of patients with the cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variant, the study provides evidence that the APOE ɛ2 genotype may contribute to a more severe cognitive impairment associated with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL); this association may be mediated by mesial temporal atrophy.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

APOE genotype may modify the cognitive manifestation among patients with CADASIL.

The mechanism underlying this clinical association needs to be explored in further studies and may shed light on future drug development.

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is the most prevalent monogenic cerebral small‐vessel disease (SVD). It is caused by pathogenic variants in the Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 3 (NOTCH3) gene mapped to the short arm of chromosome 19 (19p13.2‐p13.1) (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man number 600276). Pathogenic NOTCH3 variants are almost always stereotyped missense variants leading to loss or gain of a cysteine residue within 1 of the epidermal growth factor–like repeats (EGFRs) in the extracellular domains of the NOTCH3 protein. 1 The clinical manifestations of CADASIL, including migraine, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, cognitive impairment, gait disturbance, and psychiatric disorders, partially overlap with sporadic cerebral SVD but often have a younger age of onset and tend to be more multifaceted. Although CADASIL is a monogenic disease, substantial phenotypic heterogeneity exists on the age of symptom onset, predominant clinical presentation, and imaging severity among patients with CADASIL. The phenotypic heterogeneity is present even among individuals sharing the same pathogenic variant and within families. 2 , 3 Previous studies suggested that both NOTCH3 pathogenic variant positions 4 , 5 and concurrent vascular risk factors 6 , 7 , 8 may contribute to the risk of stroke and disability among patients with CADASIL. Conversely, factors that influence the clinical manifestations other than cerebrovascular events remain largely unknown. Some studies suggest that hypertension and smoking are associated with dementia among patients with CADASIL. 6 , 9

Cognitive impairment is 1 of the core manifestations and the major cause of disability among patients with CADASIL. It has been presumed that cognitive impairment in CADASIL is a consequence of cerebral vasculopathy. However, cerebral SVD burden, measured by structural brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), only has a weak correlation with cognitive performance in patients with CADASIL. 10 Furthermore, cerebral cortical atrophy was associated with cognitive impairment in patients with CADASIL independent of their cerebral SVD burden. 11 , 12 These observations suggest that pathomechanisms in addition to vasculopathy may also contribute to neurodegeneration in CADASIL. Investigation of the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to the variable severity of cognitive dysfunction among patients with CADASIL may reveal the mechanism underlying neurodegeneration in CADASIL. Polymorphism in the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is the most important genetic risk factor associated with sporadic Alzheimer disease, with the presence of 1 ɛ4 allele associated with 3.7 times increased risk and 1 ε2 allele associated with 40% reduced risk of developing Alzheimer disease, compared with the most common ε3ε3 genotype. 13 In addition to its association with Alzheimer pathology, more and more evidence suggests that APOE may play a role in cerebrovascular function and blood‐brain barrier integrity. 14 , 15 Meta‐analysis showed a robust, dose‐dependent association between APOE ɛ4 allele and risk of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, 16 1 of the common pathologic features of age‐related cerebral small‐vessel disease. Besides, both of the APOE ɛ4 and ɛ2 alleles are associated with increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. 17 Whether the polymorphism of APOE contributes to the clinical heterogeneity of cognitive impairment related to CADASIL remained controversial. 2 , 18

In the present study, we aimed to explore (1) the contributions of the APOE genotype and NOTCH3 pathogenic variant position to the severity of cognitive impairment among patients harboring cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants; and (2) the possible mediation effect of imaging characteristics on the relationship between genetic factors and cognitive impairment.

METHODS

Anonymized data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Participants and Cognitive Assessment

The study participants include genetically confirmed patients harboring cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants enrolled from 2 medical centers in Taiwan, the Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the National Taiwan University Hospital, between April 2015 and April 2021. The criteria for NOTCH3 genetic analysis included the following: (1) SVD evident on brain MRI and having at least 1 of the associated clinical manifestations (ie, cerebrovascular event, cognitive impairment, psychotic symptoms, gait disturbance, and migraine with aura); or (2) the presence of a family history of cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants. SVD evident on brain MRI was defined as a moderate‐to‐severe white matter hyperintensity (WMH) (Fazekas score 2 or 3 on the deep white matter [DWM] regions), 24 or at least mild WMH (Fazekas score ≥1 on the DWM regions) for subjects aged <50 years. Individuals who were asymptomatic (ie, received genetic study because of family history alone) and not having evident SVD on brain MRI were excluded from this study (Figure S1). Enrolled subjects received a standardized questionnaire to document their demographic data, the presence of specific symptoms related to CADASIL, concurrent vascular risk factors, family history for at least 3 generations, and current medication list. In addition, a fasting blood sample was collected for total cholesterol, triglycerides, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting plasma glucose, and hemoglobin A1c. Stroke was defined on the basis of the subject's reported history and verified by his/her medical record when available. Only symptomatic stroke presenting as acute‐onset focal neurologic deficit with symptoms lasting for ≥24 hours was included. The types of strokes (ie, ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke) were documented and verified by their medical record when available.

The cognitive performance of the enrolled subjects was assessed by the Taiwanese version of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) score. 19 , 20 Cognitive impairment was defined as an MMSE score <24 for patients harboring cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants. The educational level of participants was stratified into 3 groups, <6 years, 6 to 12 years, and >12 years. Less than 6 years of education indicates that the individual did not complete elementary school education. A total of 6 to 12 years of education indicates that the individual had completed the elementary, junior high, or senior high school education. More than 12 years of education indicates that the individual has received college or university education. The educational policy in Taiwan started to cover 6 years of mandatary education since 1947. According to the publicly available statistical data from the Taiwan Ministry of the Interior, updated in 2022, the proportions of individuals aged 50 to 64 years who received <6 years, 6 to 12 years, and >12 years of education were 0.2%, 64%, and 35%, respectively. The proportions of individuals aged ≥65 years who received <6 years, 6 to 12 years, and >12 years of education were 5%, 77%, and 18%, respectively. 21

This study was approved by the local ethics committees of the participating hospitals (National Taiwan University Hospital: No. 201807044RIND; Taipei Veterans General Hospital: No. 2015‐04‐005A). All investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the participants or their proxies provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples. Genetic analysis of NOTCH3 was performed using Sanger sequencing. NOTCH3 exon 11 was analyzed first because the p.R544C variant in exon 11 is the most common pathogenic variant in Taiwanese patients with CADASIL. 22 Then, for patients without pathogenic variants in exon 11, NOTCH3 exons 2 to 10 and 12 to 24 were also investigated. Only patients with cysteine‐altering pathogenic NOTCH3 variants were included in this study. Genotyping for APOE was performed by Sanger sequencing to determine the ɛ2, ɛ3, and ɛ4 variants.

Brain MRI Acquisition and Visual Rating for Imaging Characteristics

Brain MRI was performed on a 1.5‐ or 3.0‐T scanner. The scanning protocols included axial T2‐weighted fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery and coronal T1‐weighted imaging or 3‐dimensional T1‐weighted imaging. For each brain MRI, the severity of mesial temporal atrophy (MTA) and WMH was rated semiquantitatively. MTA was rated using the visual scoring system proposed by Scheltens et al. 23 Each side of the medial temporal lobe and hippocampus was scored from 0 to 4 on the coronal views of T1‐weighted imaging. A higher MTA score indicated more severe medial temporal lobe atrophy. The extent of WMH was rated using the visual scoring system developed by Fazekas et al. 24 The severity of WMH was rated from 0 to 3 on the T2‐weighted fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery images for periventricular white matter and DWM regions, separately. A higher WMH score indicated a more extensive white matter lesion. The MTA and WMH scores were rated for each hemisphere separately, and the average score from both hemispheres was calculated for each participant.

The above‐mentioned visual rating for MTA and WMH was performed by an experienced neurologist (Y.‐W.C.). To evaluate the interrater reliability of the visual rating, a subset of 30 MRI scans from this cohort was independently reviewed by another experienced neurologist (C.‐H.C.). The interrater agreements were calculated using the quadratic weighted κ values. The weighted κ values were 0.90 (95% CI, 0.82–0.98) for MTA, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.74–0.99) for DWM hyperintensity, and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.66–0.94) for periventricular white matter hyperintensity, indicating strong interrater agreements for the above ratings.

Statistical Analysis

We used independent t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables to compare the between‐group differences in demographic variables. First, we tested the effects of genetic factors and clinical variables on the MMSE score using univariate linear regression analysis. Bayesian adjustment for confounding (BAC) 25 , 26 was used to identify clinical confounders before running the multiple regression models. The 10 clinical confounders that were used for BAC included age, sex, educational level, history of ischemic stroke, history of hemorrhagic stroke, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and enrollment hospital. The algorithm was implemented in the bac function in the R package bacr. 26 The number of Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations was set to 100 000, with a burn‐in of 100 000 and a thinning parameter of 1000. Confounders selected by the BAC method were used as covariates in the multiple regression model to estimate the adjusted effects of genetic factors on the MMSE score. To compare the imaging characteristics between different APOE genotypes or NOTCH3 variants at different positions, ANCOVA was performed using a univariate general linear model with adjustment for age and sex. To explore the possible mediation effect of imaging characteristics on the relationship between genetic factors and cognitive impairment, we performed mediation analysis with linear regression models and included age, sex, and educational level as covariates, following the A Guideline for Reporting Mediation Analyses statement 27 (see Supplemental Material). The PROCESS macro, version 3.5, for SPSS was used to perform the mediation analysis. 28 The significance of the mediation effect was tested by calculating the 95% CIs using nonparametric bootstrapping of 10 000 resamples. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 246 patients harboring cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants were enrolled, among whom 150 patients had normal cognitive performance and 96 had cognitive impairment. The demographic data of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Patients who had cognitive impairment were older (67.4±9.8 versus 59.7±10.1 years; P<0.0001), had a lower educational level (9.4±4.8 versus 12.2±3.7 years; P<0.0001), and more frequently had a history of ischemic stroke (65% versus 44%; P=0.001) or concurrent gait disturbance (52% versus 26%; P<0.0001). Migraine was less frequent in patients who had cognitive impairment than in those with normal cognitive function (1% versus 10%; P=0.015). The frequencies of APOE ɛ3ɛ3, ɛ2 carriers (ɛ2ɛ3), and ɛ4 carriers (including ɛ3ɛ4 and ɛ4ɛ4) were 66%, 13%, and 22%, respectively, in patients with cognitive impairment, and 80%, 6%, and 14%, respectively, in patients with normal cognitive performance. One patient in the normal cognition group harbored the APOE ɛ2ɛ4 genotype and was excluded from further analysis considering the possible differential effect of the ɛ2 and ɛ4 alleles on cognitive and vascular outcomes. The distributions of the APOE genotypes differed significantly between patients with and without cognitive impairment (P=0.029). For imaging characteristics, patients with cognitive impairment had more advanced WMH in both the DWM and periventricular white matter and more advanced MTA than patients without cognitive impairment. The frequency of anterior temporal WMH involvement did not differ between patients with and without cognitive impairment (47% versus 40%; P=0.341).

Table 1.

Demographics of Enrolled Patients Harboring Cysteine‐Altering NOTCH3 Variants

| Variable | Total patients (N=246) | Patients without cognitive impairment (N=150)* | Patients with cognitive impairment (N=96)* | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 62.7 (10.6) | 59.7 (10.1) | 67.4 (9.8) | <0.0001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 132 (54) | 85 (49) | 47 (51) | 0.561 |

| Education, y | 11.2 (4.3) | 12.2 (3.7) | 9.4 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| NOTCH3 variant position, n (%) | 0.990 | |||

| EGFR 1–6 | 18 (7) | 11 (7) | 7 (7) | |

| EGFR 7–34 | 228 (93) | 139 (93) | 89 (93) | |

| NOTCH3 p.R544C, n (%) | 209 (85) | 130 (87) | 79 (82) | 0.349 |

| APOE genotype, n (%) | 0.029† | |||

| ɛ3ɛ3 | 183 (74) | 120 (80) | 63 (66) | |

| ɛ2ɛ3 | 21 (9) | 9 (6) | 12 (13) | |

| ɛ3ɛ4 | 40 (16) | 19 (13) | 21 (22) | |

| ɛ4ɛ4 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| ɛ2ɛ4 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| MMSE score | 23.2 (7.1) | 28.0 (1.8) | 15.7 (5.5) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical presentations, n (%) | ||||

| Stroke | 150 (61) | 81 (54) | 69 (72) | 0.005 |

| Stroke type | ||||

| Ischemic stroke | 123 (52) | 64 (44) | 59 (65) | 0.001 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 38 (16) | 21 (14) | 17 (19) | 0.368 |

| Gait disturbance | 89 (36) | 39 (26) | 50 (52) | <0.0001 |

| Psychiatric symptoms | 49 (20) | 25 (17) | 24 (25) | 0.110 |

| Migraine | 13 (6) | 12 (10) | 1 (1) | 0.015 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 132 (54) | 78 (53) | 54 (56) | 0.587 |

| Diabetes | 48 (20) | 25 (17) | 23 (24) | 0.175 |

| Dyslipidemia | 87 (35) | 58 (39) | 29 (31) | 0.169 |

| Smoking | 56 (24) | 37 (26) | 19 (21) | 0.415 |

| Alcohol | 37 (16) | 27 (19) | 10 (11) | 0.127 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 176.5 (38.9) | 179.2 (37.4) | 171.7 (41.1) | 0.209 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 103.8 (34.5) | 104.9 (33.8) | 102.0 (35.9) | 0.579 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 47.9 (12.3) | 49.1 (11.5) | 46.4 (13.2) | 0.303 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 121.1 (69.3) | 120.9 (74.6) | 121.4 (60.8) | 0.962 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 106.6 (30.4) | 107.6 (34.6) | 105.1 (22.7) | 0.605 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.89 (0.90) | 5.88 (0.91) | 5.90 (0.88) | 0.889 |

| Imaging characteristics‡ | ||||

| DWM hyperintensity score | <0.0001 | |||

| 1–1.5 | 21 (9) | 21 (14) | 0 (0) | |

| 2–2.5 | 82 (33) | 64 (43) | 18 (19) | |

| 3 | 143 (58) | 65 (43) | 78 (81) | |

| PVWM hyperintensity score | <0.0001 | |||

| 1–1.5 | 7 (3) | 7 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| 2–2.5 | 50 (20) | 44 (29) | 6 (6) | |

| 3 | 189 (77) | 99 (66) | 90 (94) | |

| MTA score | <0.0001 | |||

| 0–0.5 | 55 (22) | 52 (37) | 3 (4) | |

| 1–1.5 | 87 (35) | 59 (42) | 28 (33) | |

| 2–2.5 | 66 (27) | 26 (19) | 40 (48) | |

| 3–4 | 15 (6) | 2 (1) | 13 (16) | |

| Anterior temporal WMH, n (%) | 95 (43) | 52 (40) | 43 (47) | 0.341 |

Data are shown as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. DWM indicates deep white matter; EGFR, epidermal growth factor–like repeat; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; MTA, mesial temporal atrophy; PVWM, periventricular white matter; and WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

Cognitive impairment was defined by an MMSE score <24.

Comparison among APOE subgroups of the following: ɛ3ɛ3, ɛ2 carrier (ɛ2ɛ3), and ɛ4 carrier (ɛ3ɛ4 and ɛ4ɛ4).

DWM and PVWM hyperintensities were rated by the score of Fazekas et al,24 and MTA was rated by the score of Scheltens et al.23 Each semiquantitative score was presented as the average score from both hemispheres.

The demographics among patients with APOE ɛ3ɛ3, ɛ2 carriers, and ɛ4 carriers are shown in Table 2. The distributions of age, sex, and educational level did not differ among the 3 groups. Clinical presentations and concurrent vascular risk factor profile did not differ among the 3 groups, except for an increased frequency of hemorrhagic stroke observed in APOE ɛ3ɛ3 carriers (19%, 5%, and 8% for ɛ3ɛ3, ɛ2 carriers, and ɛ4 carriers, respectively; P=0.049). The mean MMSE score was lower in ɛ2 carriers compared with the other 2 groups (23.9±6.4, 18.7±10.4, and 22.4±7.3 for ɛ3ɛ3, ɛ2 carriers, and ɛ4 carriers, respectively; P=0.005). For imaging characteristics, the severity of WMH did not differ among the 3 APOE groups. APOE ɛ2 and ɛ4 carriers had a more advanced MTA than patients carrying the APOE ɛ3ɛ3 genotype (MTA score, 1.19±0.90, 1.58±0.71, and 1.51±0.82 for ɛ3ɛ3, ɛ2 carriers, and ɛ4 carriers, respectively; P=0.037).

Table 2.

Comparison of Clinical Information in Each APOE Genotype

| Variable | ɛ3ɛ3 (N=183) | ɛ2 Carrier (N=21) | ɛ4 Carrier (N=41) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age y | 62.7 (10.8) | 62.5 (11.7) | 62.3 (9.5) | 0.977 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 91 (50) | 11 (52) | 20 (49) | 0.964 |

| Education, y | 11.2 (4.2) | 9.7 (5.2) | 11.7 (4.4) | 0.235 |

| NOTCH3 variant position, n (%) | 0.731 | |||

| EGFR 1–6 | 12 (7) | 2 (10) | 4 (10) | |

| EGFR 7–34 | 171 (93) | 19 (90) | 37 (90) | |

| MMSE score | 23.9 (6.4) | 18.7 (10.4) | 22.4 (7.3) | 0.005 |

| MMSE‐recall score | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.3) | 0.198 |

| Clinical presentations, n (%) | ||||

| Ischemic stroke | 88 (49) | 13 (62) | 22 (58) | 0.402 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 34 (19) | 1 (5) | 3 (8) | 0.049 |

| Gait disturbance | 66 (36) | 10 (48) | 13 (32) | 0.463 |

| Psychiatric symptoms | 41 (22) | 5 (24) | 3 (7) | 0.083 |

| Migraine | 9 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 0.599 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 103 (57) | 11 (55) | 17 (42) | 0.213 |

| Diabetes | 37 (20) | 3 (15) | 8 (20) | 0.850 |

| Dyslipidemia | 67 (37) | 4 (20) | 16 (40) | 0.279 |

| Smoking | 43 (24) | 5 (25) | 8 (21) | 0.906 |

| Alcohol | 26 (15) | 4 (20) | 7 (18) | 0.760 |

| Imaging characteristics* | ||||

| DWM hyperintensity score | 2.52 (0.63) | 2.57 (0.60) | 2.34 (0.76) | 0.230 |

| PVWM hyperintensity score | 2.75 (0.48) | 2.76 (0.44) | 2.66 (0.62) | 0.533 |

| MTA score | 1.19 (0.90) | 1.58 (0.71) | 1.51 (0.82) | 0.037 |

| Anterior temporal involvement, n (%) | 68 (41) | 9 (45) | 18 (50) | 0.616 |

Data are shown as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. DWM indicates deep white matter; EGFR, epidermal growth factor–like repeat; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; MTA, mesial temporal atrophy; and PVWM, periventricular white matter.

DWM and PVWM hyperintensities were rated by the score of Fazekas et al,24 and MTA was rated by the score of Scheltens et al.23 Each semiquantitative score was presented as the average score from both hemispheres.

The pathogenic NOTCH3 variants of the enrolled subjects are shown in Table S1. Most (228/246 [93%]) of the enrolled subjects harbored pathogenic variants located in EGFR 7 to 34, and 210 (85%) of the enrolled subjects harbored the p.R544C variant. Patients carrying pathogenic variants located in EGFR 7 to 34 were older than those carrying pathogenic variants in EGFR 1 to 6 (63.6±10.3 versus 51.2±8.0 years; P<0.0001). Therefore, age was considered as a possible confounding factor when inferring the relationships between the NOTCH3 variant position and cognitive performance in the following analysis.

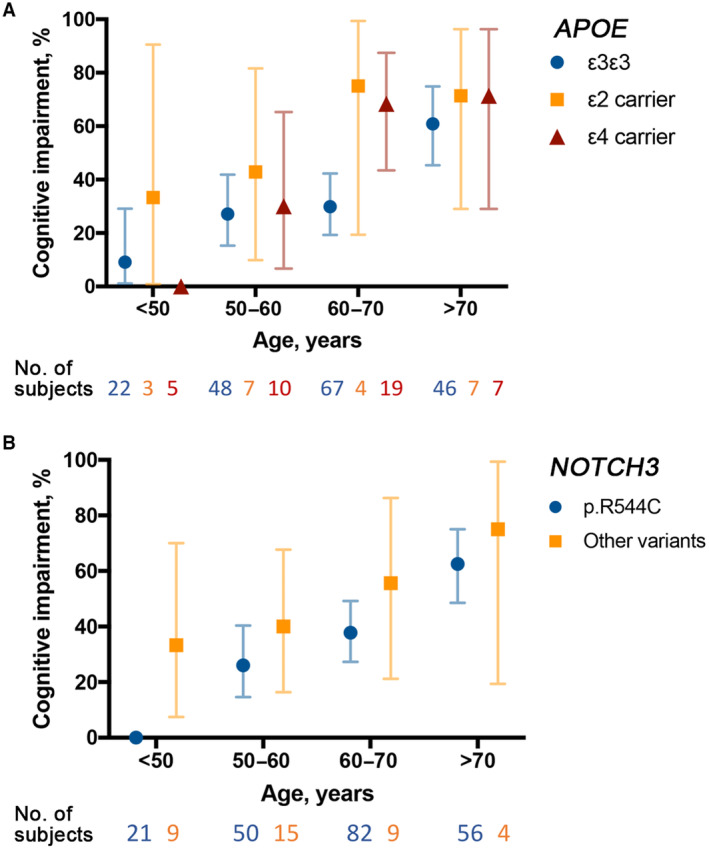

The frequencies of patients having cognitive impairment in different age strata and across different APOE and NOTCH3 genotypes are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The frequency of cognitive impairment among patients with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), stratified by age.

A, Patients were stratified according to their APOE genotype and age group. B, Patients were stratified according to their pathogenic NOTCH3 variant and age group. The 95% CI for the proportion of cognitive impairment in each subgroup was calculated using the binomial distribution method. Cognitive impairment was defined as a Mini‐Mental State Examination score <24 for patients with CADASIL.

APOE ɛ2 Allele and the NOTCH3 p.R544C Variant Are Associated With Cognitive Performance in Patients Harboring Cysteine‐Altering NOTCH3 Variants

In the univariate analysis, an older age, APOE ɛ2 allele carrier status, and a history of ischemic stroke were significantly associated with a lower MMSE score (Table S2). A higher educational level was associated with a higher MMSE score. After adjusting for age, the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant was associated with a higher MMSE score than the other pathogenic variants (adjusted B, 2.979 [95% CI, 0.610–5.347]; P=0.014; Table S3).

To estimate the effect of the APOE ɛ2 allele carrier status on the MMSE score, clinical confounders selected by the BAC method were adjusted in the multiple regression model. The result of the multiple regression model was shown in Table 3. The association between the APOE ɛ2 allele and a lower MMSE score remained statistically significant (adjusted B, 4.090 [95% CI, −6.708 to −1.473]; P=0.023) after controlling for age, educational level, and history of ischemic stroke. When assessing the effect of the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant on the MMSE score, the BAC model selected the same set of clinical confounders (namely, age, educational level, and history of ischemic stroke). The result of the multiple regression model that estimates the effect of NOTCH3 p.R544C variant on the MMSE score was shown in Table 4. The NOTCH3 p.R544C variant was significantly associated with a higher MMSE score (adjusted B, 2.854 [95% CI, 0.603–5.105]; P=0.0132) compared with other cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants, after controlling for age, educational level, and history of ischemic stroke.

Table 3.

Effect Estimates of the APOE ɛ2 Allele and Confounding Factors on Global Cognitive Performance Measured by MMSE Score, in Patients Harboring Cysteine‐Altering NOTCH3 Variants

| Clinical variables | B * | (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| APOE ɛ2 carrier vs ɛ3ɛ3 | −4.090 | (−6.708 to −1.473) | 0.0023 |

| Age, every 10 y | −2.006 | (−2.746 to −1.265) | <0.0001 |

| Education >12 vs ≤12 y | 2.481 | (0.812 to 4.151) | 0.0038 |

| Ischemic stroke | −2.617 | (−4.193 to −1.042) | 0.0012 |

MMSE indicates Mini‐Mental State Examination.

The B estimates were derived from the multiple linear regression model with confounders selected using the Bayesian adjustment for confounding method. A negative B estimate for a clinical variable indicates that the variate is associated with a lower MMSE score (ie, a poorer global cognitive performance).

Table 4.

Effect Estimates of the NOTCH3 p.R544C Variant and Confounding Factors on Global Cognitive Performance Measured by MMSE Score, in Patients Harboring Cysteine‐Altering NOTCH3 Variants

| Clinical variables | B * | (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOTCH3 p.R544C variant | 2.854 | (0.603 to 5.105) | 0.0132 |

| Age, every 10 y | −2.246 | (−3.011 to −1.480) | <0.0001 |

| Education >12 vs ≤12 y | 2.822 | (1.122 to 4.522) | 0.0012 |

| Ischemic stroke | −2.381 | (−3.985 to −0.777) | 0.0038 |

MMSE indicates Mini‐Mental State Examination.

The B estimates were derived from the multiple linear regression model with confounders selected using the Bayesian adjustment for confounding method. A negative B estimate for a clinical variable indicates that the variate is associated with a lower MMSE score (ie, a poorer global cognitive performance).

Effects of the APOE ε2 Allele and the NOTCH3 p.R544C Variant on Cognitive Performance Were Mediated by MTA and WMH

The imaging characteristics were compared among APOE ε2 carriers, ε4 carriers, and ε3ε3 carriers using ANCOVA, between patients with NOTCH3 variants residing in EGFR 1 to 6 and those with variants residing in EGFR 7 to 34, and between the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant and other pathogenic variants (Table S4). After adjusting for age and sex, patients harboring either the ɛ2 or ɛ4 allele had a more advanced MTA than APOE ɛ3ɛ3 carriers (B, 0.401 [95% CI, 0.052–0.749]; P=0.025 for APOE ɛ2 carriers, and B, 0.320 [95% CI, 0.066–0.574]; P=0.014 for APOE ɛ4 carriers). There was no statistically significant difference in the MTA score neither between NOTCH3 pathogenic variant located in EGFR 1 to 6 and variants located in EGFR 7–34 (P=0.437), nor between the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant and other pathogenic variants (P=0.460). Conversely, NOTCH3 pathogenic variants located in EGFR 1 to 6 were associated with a more advanced DWM hyperintensity than pathogenic variants located in EGFR 7 to 22 (B, 0.540 [95% CI, 0.242–0.838]; P=0.0004). The NOTCH3 p.R544C variant was associated with a less advanced DWM score (B, −0.376 [95% CI, −0.162 to −0.590]; P=0.001). The DWM hyperintensity score did not differ among patients harboring different APOE genotypes (P=0.216).

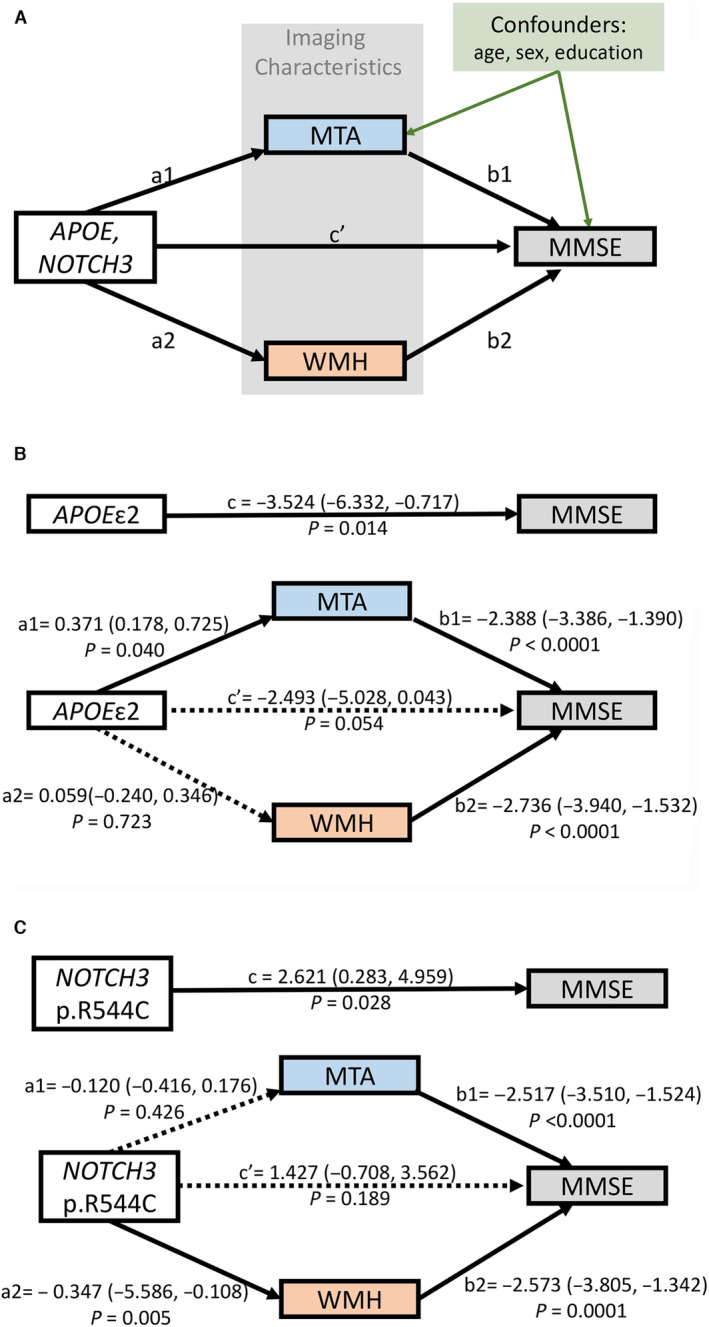

To explore how imaging characteristics influenced the relationship between genetic factors and cognitive performance, mediation analysis was performed, and the model of the hypothetical causal pathway was shown in Figure 2A. The mediation analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of MTA on the association between the APOE ɛ2 allele and the MMSE score (linear regression B estimate of indirect effect, −1.0314 [bootstrap 95% CI for the indirect effect, −2.4213 to −0.1199]). The indirect effect of WMH on the association between the APOE ɛ2 allele and the MMSE score was not statistically significant (B estimate of indirect effect, −0.1146 [bootstrap 95% CI for the indirect effect, −0.8600 to 0.6528]; Figure 2B). In contrast, there was a significant indirect effect of WMH on the association between the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant and a milder cognitive impairment (B estimate of indirect effect, 0.8928 [bootstrap 95% CI for the indirect effect, 0.2377–1.6772]), whereas the indirect effect of MTA on the association between the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant and MMSE score was not statistically significant (B estimate of indirect effect, 0.3014 [bootstrap 95% CI for the indirect effect, −0.4620 to 1.1257]; Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Relationship between genetic factors, imaging markers, and cognitive performance, revealed by mediation analysis.

A, Model of the hypothetical causal pathway in cognitive impairment of patients with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. The total effect of genetic factors on the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was designated as c. The direct effects of genetic factors on imaging markers were designated as a1 (for mesial temporal atrophy [MTA]) and a2 (for white matter hyperintensity [WMH]), and the direct effects of these imaging markers on the MMSE score were designated as b1 (for MTA) and b2 (for WMH). The remaining effect of genetic factors on the MMSE score after adjusting for imaging markers was designated c′. Total effect (c)=direct effect (c′)+indirect effects (a1b1+a2b2). The effect estimates of the model were derived from the B estimate of linear regression analysis. Age, sex, and educational level were adjusted for all of the linear regression models. B, APOE ɛ2 carrier status was associated with a lower MMSE score than the other APOE genotypes. The relationship between the APOE ɛ2 allele and a lower MMSE score was mediated by MTA but not WMH. C, The NOTCH3 p.R544C variant was associated with a higher MMSE score than the other pathogenic variants. The relationship between the p.R544C variant and a higher MMSE score was mediated by WMH but not MTA.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated 3 major findings among patients harboring cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants. First, the APOE ɛ2 allele was associated with worse cognitive performance, and the association was mediated by MTA but was independent of the stroke history and WMH burden. Second, patients harboring the NOTCH3 p.R544C showed a milder cognitive impairment, and this relationship was mediated by the severity of WMH. Third, MTA and WMH were independently associated with cognitive impairment in patients harboring cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants.

The role of APOE genotypes in the disease severity of CADASIL has been explored in a few studies with inconsistent results. A CADASIL cohort from the United Kingdom including 123 patients found no significant association between APOE genotypes and dementia risks. 2 However, in a Korean cohort that enrolled 87 patients with CADASIL mostly harboring the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant, the APOE ɛ4 allele was associated with an increased risk of incident dementia during an average follow‐up of 67 months. 18 In the present study, we enrolled 246 patients harboring cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants and found a significant association between the APOE ɛ2 allele and a lower MMSE sore. Although the APOE ɛ4 allele was not a significant contributor to cognitive impairment in our cohort, it was associated with more advanced MTA. Whether the APOE ɛ4 allele is associated with accelerated conversion to dementia cannot be assessed in this cross‐sectional study and should be investigated in additional longitudinal follow‐up studies.

Interestingly, the relationship between the APOE ɛ2 allele and cognitive impairment was mediated by MTA rather than WMH. In a few studies investigating subjects with sporadic SVD 29 and Alzheimer disease, 30 the APOE ɛ2 allele was associated with a more advanced white matter disease burden. In a large European CADASIL cohort of 488 patients with a median age of ≈50 years, Gesierich et al showed that the APOE ɛ2 allele was associated with an increased WMH volume compared with the ɛ3ɛ3 genotype. 31 Compared with the European cohort, participants in the present study were older (mean age, 63 years) and predominantly harbored the p.R544C variant on EGFR13/14. In addition, the severity of WMH was measured by the semiquantitative score of Fazekas et al in the present study, whereas WMH volume was quantitatively measured by Gesierich et al. We cannot exclude the possibility that the insignificant association between the APOE ɛ2 allele and WMH severity was related to the ceiling effect of the score of Fazekas et al used in the present study. 32 Alternatively, we found that the association between the APOE ɛ2 allele and cognitive impairment was mediated by MTA in the present study, suggesting the possibility of other neurodegenerative processes in addition to arteriopathy. The APOE ɛ4 allele is known to be associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer disease, whereas the ɛ2 allele is protective against developing Alzheimer disease. 18 Alternatively, a few studies have suggested a role of the APOE ɛ2 allele in primary τ pathology. The APOE ɛ2 allele was associated with increased τ pathology in progressive supranuclear gaze palsy, a neurodegenerative disease caused by primary tauopathy. 33 The APOE ɛ2 allele was more frequent in primary age‐related tauopathy 34 and in mild cognitive impairment related to suspected non–Alzheimer disease pathophysiology. 35 Whether τ pathology plays a role in the neurodegeneration of CADASIL is worth exploring in future studies. The contribution of other neurodegenerative processes in addition to NOTCH3‐related arteriopathy may be more influential for aged patients with CADASIL than for younger subjects.

The influence of the NOTCH3 variant position on disease severity has been reported in several recent studies. Patients harboring NOTCH3 variants located in EGFR 1 to 6 had a higher vascular NOTCH3 protein aggregation load than those harboring NOTCH3 variants in EGFR 7 to 34. 36 Clinically, NOTCH3 variants located in EGFR 1 to 6 are associated with an earlier age of stroke onset, 4 a higher white matter disease and lacune burden, 4 , 5 and worse survival. 4 Consistent with previous studies, we found a greater WMH burden for patients harboring NOTCH3 variants located in EGFR 1 to 6. Meanwhile, the severity of cognitive impairment was comparable between patients with NOTCH3 variants located in EGFR 7 to 34 and those with variants in EGFR 1 to 6. Consistent with our findings, in a recent investigation that enrolled 176 patients with CADASIL, among whom 73% harbored NOTCH3 variants located in EGFR 1 to 6, the association between NOTCH3 variant position (located in EGFR 1–6 versus EGFR 7–34) and vascular cognitive impairment was nonsignificant. 37 Interestingly, we found a better cognitive performance in patients harboring the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant than other pathogenic variants in the present study. Previous epidemiologic studies showed that the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant was associated with a later age of onset and less frequent anterior temporal pole involvement. 22 , 38 , 39 Cognitive impairment was reported to be more frequent in patients harboring the p.R544C variant, although patients harboring the p.R544C variant were older than those with other NOTCH3 pathogenic variants in these patient cohorts. 22 , 38 In the present study, the p.R544C variant was associated with milder cognitive impairment after adjusting for age. Unlike other cysteine‐altering pathogenic variants that located within the 34 EGFR domains, the p.R544C variant is located at the boundary of EGFR 13 and EGFR 14 of the NOTCH3 protein (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q9UM47). The unique position of the p.R544C variant may contribute to specific conformational changes in the mutant protein, therefore causing specific clinical features associated with the p.R544C variant.

There are some limitations of the present study. First of all, the association between genetic factors and cognitive performance was assessed cross‐sectionally in the present study. Further longitudinal follow‐up studies are crucial to investigate the role of APOE and NOTCH3 genotypes on cognitive dysfunction among patients with CADASIL. Second, most of the enrolled subjects harbored pathogenic variants located in EGFR 7 to 34. Therefore, this study may be underpowered to investigate the role of NOTCH3 variant position on cognitive performance.

CONCLUSIONS

The APOE ɛ2 allele was associated with worse cognitive function and more advanced MTA, whereas the NOTCH3 p.R544C variant is associated with a milder cognitive impairment and less severe WMH. The APOE genotype and NOTCH3 pathogenic variant position may contribute to different aspects of neurodegeneration in CADASIL.

Sources of Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (grant 109‐2628‐B075‐025); Taipei Veterans General Hospital–National Taiwan University Hospital Joint Research Program (grant VN108‐08); National Taiwan University Hospital, Hsin‐Chu Branch, Taiwan (grant 110‐HCH030), and the Academia Sinica, Taiwan (grant AS‐GC‐111‐L04).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1–S4

Figure S1

Acknowledgments

We express our deepest gratitude to all the participants in the study. We also would like to express our thanks to the staff of the National Taiwan University Hospital–Statistical Consulting Unit for statistical consultation. Author contributions: conceptualization: Drs Lee and Tang; data curation: Drs Cheng, Liao, Chen, Chung, Lee, and Tang; formal analysis: Drs Cheng, Chang, and Fann; investigation: Drs Cheng, Liao, Chen, and Chung; resources: Drs Liao, Lee, and Tang; writing (original draft): Drs Cheng and Chang; writing (review and editing): Drs Liao, Lee, Tang, and Fann.

This article was sent to Kori S. Zachrison, MD, MSc, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.032689

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

Contributor Information

Yi‐Chung Lee, Email: ycli@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Sung‐Chun Tang, Email: sctang@ntuh.gov.tw.

References

- 1. Joutel A, Vahedi K, Corpechot C, Troesch A, Chabriat H, Vayssière C, Cruaud C, Maciazek J, Weissenbach J, Bousser M‐G, et al. Strong clustering and stereotyped nature of Notch3 mutations in CADASIL patients. Lancet. 1997;350:1511–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)08083-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singhal S, Bevan S, Barrick T, Rich P, Markus HS. The influence of genetic and cardiovascular risk factors on the CADASIL phenotype. Brain. 2004;127:2031–2038. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dziewulska D, Sulejczak D, Wezyk M. What factors determine phenotype of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL)? Considerations in the context of a novel pathogenic R110C mutation in the NOTCH3 gene. Folia Neuropathol. 2017;55:295–300. doi: 10.5114/fn.2017.72387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rutten JW, Van Eijsden BJ, Duering M, Jouvent E, Opherk C, Pantoni L, Federico A, Dichgans M, Markus HS, Chabriat H, et al. The effect of NOTCH3 pathogenic variant position on CADASIL disease severity: NOTCH3 EGFr 1‐6 pathogenic variant are associated with a more severe phenotype and lower survival compared with EGFr 7‐34 pathogenic variant. Genet Med. 2019;21:676–682. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0088-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rutten JW, Dauwerse HG, Gravesteijn G, van Belzen MJ, van der Grond J, Polke JM, Bernal‐Quiros M, Lesnik Oberstein SA. Archetypal NOTCH3 mutations frequent in public exome: implications for CADASIL. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3:844–853. doi: 10.1002/acn3.344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ciolli L, Pescini F, Salvadori E, Del Bene A, Pracucci G, Poggesi A, Nannucci S, Valenti R, Basile AM, Squarzanti F, et al. Influence of vascular risk factors and neuropsychological profile on functional performances in CADASIL: results from the MIcrovascular LEukoencephalopathy Study (MILES). Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:65–71. doi: 10.1111/ene.12241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adib‐Samii P, Brice G, Martin RJ, Markus HS. Clinical spectrum of CADASIL and the effect of cardiovascular risk factors on phenotype: study in 200 consecutively recruited individuals. Stroke. 2010;41:630–634. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Viswanathan A, Guichard JP, Gschwendtner A, Buffon F, Cumurcuic R, Boutron C, Vicaut E, Holtmannspotter M, Pachai C, Bousser MG, et al. Blood pressure and haemoglobin A1c are associated with microhaemorrhage in CADASIL: a two‐centre cohort study. Brain. 2006;129:2375–2383. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chabriat H, Herve D, Duering M, Godin O, Jouvent E, Opherk C, Alili N, Reyes S, Jabouley A, Zieren N, et al. Predictors of clinical worsening in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2016;47:4–11. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.115.010696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jouvent E, Duering M, Chabriat H. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: lessons from neuroimaging. Stroke. 2020;51:21–28. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.024152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shi Y, Li S, Li W, Zhang C, Guo L, Pan Y, Zhou X, Wang X, Niu S, Yu X, et al. MRI lesion load of cerebral small vessel disease and cognitive impairment in patients with CADASIL. Front Neurol. 2018;9:862. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viswanathan A, Godin O, Jouvent E, O'Sullivan M, Gschwendtner A, Peters N, Duering M, Guichard JP, Holtmannspötter M, Dufouil C, et al. Impact of MRI markers in subcortical vascular dementia: a multi‐modal analysis in CADASIL. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1629–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Serrano‐Pozo A, Das S, Hyman BT. APOE and Alzheimer's disease: advances in genetics, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:68–80. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(20)30412-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Montagne A, Nation DA, Sagare AP, Barisano G, Sweeney MD, Chakhoyan A, Pachicano M, Joe E, Nelson AR, D'Orazio LM, et al. APOE4 leads to blood‐brain barrier dysfunction predicting cognitive decline. Nature. 2020;581:71–76. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2247-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tai LM, Thomas R, Marottoli FM, Koster KP, Kanekiyo T, Morris AW, Bu G. The role of APOE in cerebrovascular dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:709–723. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1547-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rannikmae K, Samarasekera N, Martinez‐Gonzalez NA, Al‐Shahi Salman R, Sudlow CL. Genetics of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:901–908. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carpenter AM, Singh IP, Gandhi CD, Prestigiacomo CJ. Genetic risk factors for spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:40–49. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee JS, Ko KH, Oh JH, Kim JG, Kang CH, Song SK, Kang SY, Kang JH, Park JH, Koh MJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 is associated with the development of incident dementia in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy patients with p.Arg544Cys mutation. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:591879. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.591879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yip P‐K, Shyu Y‐I, Liu S‐I, Lee J‐Y, Chou C‐F, Chen R‐C. An epidemiological survey of dementia among elderly in an urban district of Taipei. Acta Neurol Sin. 1992;1:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shyu YI, Yip PK. Factor structure and explanatory variables of the mini‐mental state examination (MMSE) for elderly persons in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100:676–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Department of Household Registration . Interior Statistics Bulletin_Educational Attainment. Taiwan Ministry of the Interior. 2023. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.moi.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=9&s=279021

- 22. Liao YC, Hsiao CT, Fuh JL, Chern CM, Lee WJ, Guo YC, Wang SJ, Lee IH, Liu YT, Wang YF, et al. Characterization of CADASIL among the Han Chinese in Taiwan: distinct genotypic and phenotypic profiles. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Leys D, Pruvo JP, Nauta JJ, Vermersch P, Steinling M, Valk J. A semiquantative rating scale for the assessment of signal hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Sci. 1993;114:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90041-v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–356. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang C, Parmigiani G, Dominici F. Bayesian effect estimation accounting for adjustment uncertainty. Biometrics. 2012;68:661–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang C, Dominici F, Parmigiani G, Zigler CM. Accounting for uncertainty in confounder and effect modifier selection when estimating average causal effects in generalized linear models. Biometrics. 2015;71:654–665. doi: 10.1111/biom.12315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee H, Cashin AG, Lamb SE, Hopewell S, Vansteelandt S, VanderWeele TJ, MacKinnon DP, Mansell G, Collins GS, Golub RM, et al. A guideline for reporting mediation analyses of randomized trials and observational studies: the AGReMA statement. JAMA. 2021;326:1045–1056. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression‐Based Approach. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schilling S, DeStefano AL, Sachdev PS, Choi SH, Mather KA, DeCarli CD, Wen W, Hogh P, Raz N, Au R, et al. APOE genotype and MRI markers of cerebrovascular disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neurology. 2013;81:292–300. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfda4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Groot C, Sudre CH, Barkhof F, Teunissen CE, van Berckel BNM, Seo SW, Ourselin S, Scheltens P, Cardoso MJ, van der Flier WM, et al. Clinical phenotype, atrophy, and small vessel disease in APOEε2 carriers with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018;91:e1851–e1859. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gesierich B, Opherk C, Rosand J, Gonik M, Malik R, Jouvent E, Herve D, Adib‐Samii P, Bevan S, Pianese L, et al. APOE varepsilon2 is associated with white matter hyperintensity volume in CADASIL. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:199–203. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Straaten EC, Fazekas F, Rostrup E, Scheltens P, Schmidt R, Pantoni L, Inzitari D, Waldemar G, Erkinjuntti T, Mantyla R, et al. Impact of white matter hyperintensities scoring method on correlations with clinical data: the LADIS study. Stroke. 2006;37:836–840. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000202585.26325.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhao N, Liu CC, Van Ingelgom AJ, Linares C, Kurti A, Knight JA, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, Shinohara M, Martens YA, et al. APOE epsilon2 is associated with increased tau pathology in primary tauopathy. Nature Commun. 2018;9:4388. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06783-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Robinson AC, Davidson YS, Roncaroli F, Minshull J, Tinkler P, Horan MA, Payton A, Pendleton N, Mann DMA. Influence of APOE genotype in primary age‐related tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8:215. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-01095-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schreiber S, Schreiber F, Lockhart SN, Horng A, Bejanin A, Landau SM, Jagust WJ. Alzheimer disease signature neurodegeneration and APOE genotype in mild cognitive impairment with suspected non‐Alzheimer disease pathophysiology. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:650–659. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gravesteijn G, Hack RJ, Mulder AA, Cerfontaine MN, van Doorn R, Hegeman IM, Jost CR, Rutten JW, Lesnik Oberstein SAJ. NOTCH3 variant position is associated with NOTCH3 aggregation load in CADASIL vasculature. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2022;48:e12751. doi: 10.1111/nan.12751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jolly AA, Nannoni S, Edwards H, Morris RG, Markus HS. Prevalence and predictors of vascular cognitive impairment in patients with CADASIL. Neurology. 2022;99:e453–e461. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000200607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen S, Ni W, Yin XZ, Liu HQ, Lu C, Zheng QJ, Zhao GX, Xu YF, Wu L, Zhang L, et al. Clinical features and mutation spectrum in Chinese patients with CADASIL: a multicenter retrospective study. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23:707–716. doi: 10.1111/cns.12719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim YE, Yoon CW, Seo SW, Ki CS, Kim YB, Kim JW, Bang OY, Lee KH, Kim GM, Chung CS, et al. Spectrum of NOTCH3 mutations in Korean patients with clinically suspicious cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:e721–e726. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1–S4

Figure S1