Abstract

Adolescence is a critical period for establishing habits and engaging in health behaviors to prevent future cancers. Rural areas tend to have higher rates of cancer-related morbidity and mortality as well as higher rates of cancer-risk factors among adolescents. Rural primary care clinicians are well-positioned to address these risk factors. Our goal was to identify existing literature on adolescent cancer prevention in rural primary care and to classify key barriers and facilitators to implementing interventions in such settings.

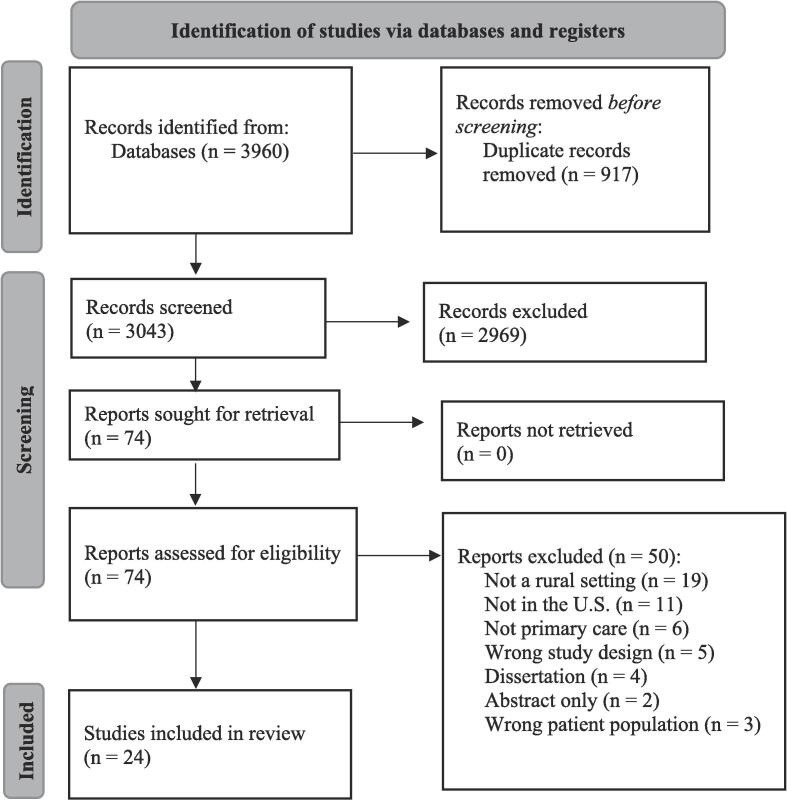

We searched the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE®; Ovid APA PsycInfo; Cochrane Library; CINAHL; and Scopus. Studies were included if they reported on provider and/or clinic-level interventions in rural primary care clinics addressing one of these four behaviors (obesity, tobacco, sun exposure, HPV vaccination) among adolescent populations. We identified 3,403 unique studies and 24 met inclusion criteria for this review.

16 addressed obesity, 6 addressed HPV vaccination, 1 addressed skin cancer, and 1 addressed multiple behaviors including obesity and tobacco use. 10 studies were either non-randomized experimental designs (n = 8) or randomized controlled trials (n = 2). The remaining were observational or descriptive research.

We found a dearth of studies addressing implementation of adolescent cancer prevention interventions in rural primary care settings. Priorities to address this should include further research and increased funding to support EBI adaptation and implementation in rural clinics to reduce urban–rural cancer inequities.

Keywords: Rural health, Adolescent health, Cancer prevention, Primary care, Scoping review

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a critical time to establish healthy habits and receive routine preventive care to prevent future cancer-related morbidity and mortality. There is substantial evidence that adolescence and early adulthood are a period of “cumulative risk” for later onset cancers (Biro and Wolff, 2011, National Cancer Institute (NCI), 2010, Fuemmeler et al., 2009, Linos et al., 2008), making it a particularly important time for intervention (Santelli et al., 2013). Early intervention and prevention are critically needed in rural areas, where populations are at a higher risk for all cancers combined, cancers associated with tobacco use, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (Zahnd et al., 2018). Moreover, rural areas, home to approximately 20 % of the United States population (Ratcliffe et al., 2016) have higher levels of cancer risk factors including obesity (Lundeen et al., 2016), tobacco use (Pesko and Robarts, 2017), harmful sun exposure behaviors (Nagelhout et al., 2019), and low HPV vaccination uptake (Pingali et al., 2020).

These high rates of cancer incidence coupled with low rates of cancer prevention behaviors indicate that early action to promote primary prevention (i.e., prevent the development of cancers later in life) is needed for rural adolescent populations to reverse the trend of urban–rural cancer inequities. Pediatric and family medicine providers, who provide care for patients ranging from young children to adolescents and young adults, are well positioned to advocate for primary prevention in adolescent populations and to implement existing evidence-based interventions (EBIs) to promote these prevention-focused behaviors. However, previous research has identified that rural clinics often have diminished capacity for implementing such EBIs compared to urban clinics (Cohen et al., 2018, Fagnan et al., 2021). Moreover, EBIs are often developed at large, well-resourced medical centers and may not directly translate to rural settings (Smith et al., 2016). Thus, while rural primary care settings are critical for addressing cancer prevention in adolescents in the form of primary prevention, these clinics may have difficulty effectively implementing EBIs; an issue which could be contributing to these persistent urban–rural cancer inequities.

In this review we focus on HPV vaccination, obesity, smoking, and sun exposure, all health topics that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (Meites et al., 2016) and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) have published specific guidance on (US Preventive Services Task Force et al., 2017, US Preventive Services Task Force et al., 2018, US Preventive Services Task Force et al., 2020) (Table 1). Importantly, these four areas are ideal to address or intervene on during adolescence to prevent negative health outcomes in adulthood, including cancer-related morbidity and mortality. While common, HPV infection, if left untreated, can result in future cervical, anal, vaginal, vulvar, penile, or oropharyngeal cancers (Watson et al., 2008). The HPV vaccine is highly effective in preventing infection and cancers when administered in adolescence (McClung et al., 2008) The association between obesity and multiple types of cancer is well-established (Calle et al., 2003), with growing evidence that obesity in childhood and adolescence specifically is contributing to adulthood cancer morbidity and mortality (Weihe et al., 2020). Tobacco use is related to 10 types of cancer, including lung cancers, and preventing and stopping tobacco use early is critical. In the United States, almost 90 % of adult smokers reported they began smoking before age 18 (USDHHS, 2012), meaning that adolescence is an ideal time for intervention. Finally, sun exposure in early childhood and adolescence is associated with development of melanoma later in life (Lin et al., 2011), indicating that developing good habits for sun protection early is key to prevention of future cancers. Intervening during adolescence could help to address urban–rural cancer inequities and reduce overall cancer burden, however more insight is needed to understand implementation issues specifically in rural, primary care settings.

Table 1.

ACIP and USPSTF Recommendations for cancer-prevention health topics for adolescents.

| Topic | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| HPV vaccination | ACIP: All adolescents should receive 2 doses of the vaccine at ages 11–12, may begin series at age 9. If series is begun after age 15, 3 doses are needed (Meites et al., 2016). |

| Obesity | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen for obesity in children and adolescents 6 years and older and offer or refer them to comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions to promote improvements in weight status (USPSTF et al., 2017). |

| Smoking | The USPSTF recommends that primary care clinicians provide interventions, including education or brief counseling, to prevent initiation of tobacco use among school-aged children and adolescents (USPSTF et al., 2020). |

| Sun exposure | The USPSTF recommends counseling young adults, adolescents, children, and parents of young children about minimizing exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation for persons aged 6 months to 24 years with fair skin types to reduce their risk of skin cancer (USPTF et al., 2018). |

We sought to gain a better understanding of the implementation of EBIs with adolescents related to these four topics in rural primary care settings. Our goal in this scoping review was to identify existing literature on adolescent cancer prevention in rural primary care and to classify key barriers and facilitators to implementing interventions in such settings.

2. Methods

The protocol for this study followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) template (Aromataris and Munn, 2020) for scoping reviews (registered with Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AW5M8)) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews checklist (Tricco et al., 2018). Scoping reviews are appropriate for topics, such as this one, where the goal is to explore what literature exists and what gaps may exist. A comprehensive literature search was conducted by a medical librarian on April 6th, 2022, using the following bibliographic databases from inception: Ovid MEDLINE® (ALL-1946 to Present); Ovid APA PsycInfo (1967 to present); Cochrane Library (Wiley); CINAHL with Full Text (EBSCO); and Scopus (Elsevier). No article type, date, or language restrictions were included in the search. The full Ovid MEDLINE search strategy is available in Supplemental Table 1.

2.1. Study selection

The 3,960 results produced from the database searches were imported into Covidence, a systematic review screening tool, and duplicates were removed. The remaining 3,043 unique citations were screened by title and abstract against predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria by the review team (GR, PW, MG). Each article was screened by two reviewers and once all screening was complete, the review team met to discuss any articles in which reviewers disagreed and establish consensus together. To be eligible for inclusion, articles had to meet the following criteria: (1) focus on patients between ages 9 and 17; (2) take place in a rural primary care setting; and (3) address a provider and/or clinic-level intervention to promote one of the following cancer prevention topics: HPV vaccination, tobacco use counseling or education, behavioral counseling for skin cancer prevention, or obesity screening and/or referral to behavioral interventions. While there are many definitions of how to categorize geographies as rural (e.g. Rural Urban Commuting Areas, Frontier and Remote, Rural Urban Continuum Codes, etc.), for this purpose we defined rural broadly and categorized articles as taking place in a rural population if the authors used any definition or referred to the location as “rural,” “remote,” “non-metropolitan.” Both experimental studies that included information on barriers and facilitators and non-experimental studies were considered eligible. Exclusion criteria included: (1) dissertations, conference abstracts, or trial registrations; (2) studies that took place outside of the United States; and (3) studies in a language other than English. There were 74 articles selected for full‐text review; 24 of which met inclusion criteria for this study. Reference lists and forward citations were gathered and deduplicated, producing an additional 862 citations for screening. These citations were screened in the same way as described above and resulted in no additional articles included in the review. See Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram outlining the study selection process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

2.2. Data abstraction

A data abstraction template was created, drawing from JBI protocol and our research questions for this project, and the data abstraction team (GR, PW, AB, MG) tested the abstraction form using four articles. Each team member completed the abstraction and then the team met to review and edit the form. Once finalized, the remaining articles were split among team members. Each article was abstracted by two team members and then abstractions were reviewed by the lead author to establish consensus.

2.3. Summarizing results

To organize the barriers and facilitators identified in these studies we used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) domains (Damschroder et al., 2009). The CFIR was designed to help researchers consider multi-level influential factors on implementation and has been used in numerous studies to identify barriers and facilitators to uptake of evidence-based practices in healthcare settings (Kadu and Stolee, 2015, Garbutt et al., 2018). Briefly, the five domains of the CFIR are: outer setting (factors external to the implementation setting), inner setting (characteristics of the implementing organization), individuals involved (key individuals with influence over implementation), implementation process, and intervention characteristics. We further divided some of these domains to provide clarity to the barriers and facilitators identified, for example, the outer setting was further divided into community- and patient-levels. Once barriers and facilitators in each study were identified, data abstractors coded them using the five CFIR domains.

3. Results

3.1. Summary

Of the 24 articles we identified in our review, 16 addressed obesity (Anti et al., 2016, Findholt et al., 2013, Gibson, 2016, Gortmaker et al., 2015, Hyde and McPeters, 2022, Okihiro et al., 2013, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Polacsek et al., 2009, Polacsek et al., 2014, San Giovanni et al., 2021, Shaikh et al., 2014, Shaikh et al., 2011, Shaikh et al., 2015, Silberberg et al., 2012, Thornberry et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2007), six addressed HPV vaccination (Askelson et al., 2019, Beck et al., 2021, Gunn et al., 2020, Huey et al., 2009, McLean et al., 2017, Szilagyi et al., 2015), one addressed skin cancer (Dietrich et al., 2000) one study addressed multiple behaviors including tobacco (Cifuentes et al., 2005). Ten studies were either non-randomized experimental designs (n = 8) or randomized controlled trials (n = 2) and the remaining studies were observational or descriptive research (interviews or surveys). The majority took place in multiple types of settings (e.g., pediatric clinic, family practice, academic medical center). Only four provided details on how they defined rurality (e.g., Rural-Urban Commuting Codes or Rural-Urban Commuting Areas), and the other 20 simply used the term “rural” to define the setting. Table 2 outlines summary information for all abstracted articles including study objectives and overview of results.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in review (n = 24).

| Title | Year | Setting | Topic covered | Aims or objectives of study | Study design | Outcomes assessed and key measures | Brief overview of key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Doctor Will “Friend” You Now: A Qualitative Study on Adolescents' Preferences for Weight Management App Features (San Giovanni et al., 2021) | 2021 | Pediatric clinic; Academic medical center | Obesity | Explore adolescent preferences about a technology-based weight management intervention | Qualitative research | Exploratory outcomes (qualitative) | The use of technology applications was promoted by familiarity, ease of use, and accessibility. Preferred features included nutrition education, recording of physical activity, self-monitoring, and social connection. Barriers included problems with app features, speed, excess information, layout/user design, and privacy concerns. |

| Provider Practice and Perceptions of Pediatric Obesity in Appalachian Kentucky (Thornberry et al., 2019) | 2019 | Other: non-specified primary care | Obesity | Explore current practices for managing pediatric obesity | Survey research | Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | Adherence to expert recommendations for managing pediatric obesity were mixed: 67 % of providers reported always or almost always using BMI percentiles; 61 % reported never using waist circumference to assess obesity; 53 % reported almost always discussing physical activity. |

| Translation of clinical practice guidelines for childhood obesity prevention in primary care mobilizes a rural Midwest community (Gibson, 2016) | 2014 | Rural health clinic | Obesity | To assess effectiveness of using the 5210 program to improve childhood obesity | Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes; Process outcomes | Documentation of BMI increased from 27 to 98 %; educational counseling increased from 9 to 87 %; accurate diagnosis of obesity increased from 0 to 32 %. Providers reported that intervention was appropriate at acute and well child visits and that they focused on messaging around eating more fruits and vegetables; watching less television; drinking more water/fewer sugar-based beverages |

| Promoting Weight Maintenance among Overweight and Obese Hispanic Children in a Rural Practice (Parra-Medina et al., 2015) | 2015 | Rural health clinic | Obesity | To evaluate an obesity management intervention for Hispanic children and their parents | Randomized controlled trial | Intervention outcomes | Greater proportion of children in standard care group in increased waist circumference and weight gain compared to intervention group. Controlling for demographic factors, odds of weight gain was reduced by 75 % for children in intervention group. |

| Organizing for Quality Improvement in Health Care: An Example From Childhood Obesity Prevention (Shaikh et al., 2015) | 2015 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice; Other: Indian Health Service Clinic | Obesity | To evaluate how a telehealth community of practice QI intervention addressed rural clinic's challenges related to translating evidence to practice for preventing and managing obesity | Qualitative research | Process outcomes; Exploratory outcomes (qualitative) | Barriers included staffing capacity and resources, lack of time, lack of patient follow-up, cultural concerns in addressing BMI, and concerns around social determinants of health. Facilitators reported were the use of clinic champions, efforts to align the intervention with established practices, clear and consistent communication, and alignment of intervention with local/community resources. |

| Collaborative practice improvement for childhood obesity in rural clinics: the Healthy Eating Active Living Telehealth Community of Practice (HEALTH COP) (Shaikh et al., 2014) | 2014 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | Obesity | Assess a virtual quality improvement project focused on adherence to clinical guidelines to treat childhood obesity | Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes | Significant increase in documentation of BMI percentile and weight category by clinicians. Clinicians covered an average of 0.8 more related educational topics per visit compared to pre-intervention. Parents’ report of use of family-centered care did not differ pre and post-intervention. |

| Evaluation of a primary care intervention on body mass index: the Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative (Gortmaker et al., 2015) | 2015 | Other: non-specified primary care clinics | Obesity | Assess impact of primary care intervention to change BMI z-score trajectories for overweight and obese pediatric patients | Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes | A decrease in growth of BMI z-score for subjects with obesity in intervention and control sites was observed as well as a significant decline in rate of increase of BMI z-score for patients with overweight and healthy weight. However here was no evidence of an overall intervention effect. |

| Implementing the obesity care model at a community health center in Hawaii to address childhood obesity (Okihiro et al., 2013) | 2013 | FQHC/CHC | Obesity | Assess a quality improvement project to improve obesity management in pediatric primary care | Mixed methods | Intervention outcomes; Exploratory outcomes (qualitative) | Integration of nutrition and behavioral health services within pediatric practices was achieved. During project period BMI was assessed at 100 % of well-child visits. Participants reported improved collaboration between staff and improved awareness of pediatric obesity. |

| Perceived barriers, resources, and training needs of rural primary care providers relevant to the management of childhood obesity (Findholt et al., 2013) | 2013 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice; Rural health clinic | Obesity | To explore perceived barriers, resources, and training needs of rural primary care providers to assess, treat, and prevent pediatric obesity | Qualitative research | Exploratory outcomes (qualitative) | Practice barriers included time constraints, lack of reimbursement, few opportunities to detect obesity Clinician barriers included limited knowledge. Family-patient barriers included family lifestyle and lack of parent motivation to change; low family income and lack of health insurance; sensitivity of the issue Community barriers included lack of pediatric sub-specialists, few community resources. Sociocultural barriers included sociocultural influences; high prevalence of childhood obesity Resources needed were hospital dietitians (underutilized) handouts/patient-facing materials; clinic and/or community-based programming; interest in learning about recommended best practices for assessment/monitoring, how to motivate parents. |

| Impact of a primary care intervention on physician practice and patient and family behavior: keep ME Healthy---the Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative (Polacsek et al., 2009) | 2009 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | Obesity | To evaluate a clinical decision support and family-centered intervention on pediatric overweight and obesity | Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes | In pre-post assessment: significantly higher rate of BMI assessment, BMI percentile, weight classification, and use of intervention screening tool; Parents reported discussion of all intervention behaviors; reports of counseling were higher in intervention group compared to control |

| Pediatric obesity management in rural clinics in California and the role of telehealth in distance education (Shaikh et al., 2011) | 2011 | FQHC/CHC; Rural health clinic | Obesity | Assess needs of health care providers to address pediatric obesity through telehealth |

Survey research | Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | On a five-point scale, most providers rated their self-efficacy in being able to address pediatric obesity as either a 2 or 3. Commonly reported barriers were lack of local weight management programs, low patient motivation, and little family involvement. The majority of participants already used telehealth services and were interested in participating in continuing education on pediatric obesity via telehealth. |

| Treating pediatric obesity in the primary care setting to prevent chronic disease: perceptions and knowledge of providers and staff (Silberberg et al., 2012) | 2012 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice; FQHC/CHC | Obesity | Assess primary care provider's and staff's perceptions and knowledge toward pediatric obesity treatment and dietitian services | Survey research | Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | Participating providers reported high levels of comfort addressing pediatric obesity, but reported very low levels of perceived effectiveness to impact pediatric obesity. For example almost 80 % felt comfortable or very comfortable raising the issue of a child being overweight but only 60 % felt that would be effective to impact weight. |

| Child overweight interventions in rural primary care practice: a survey of primary care providers in southern Appalachia (Wu et al., 2007) | 2007 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice; Academic medical center | Obesity | Explore primary care practitioners’ current practices to address childhood overweight and obesity in southern Appalachia | Survey research | Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | Participating primary care providers had positive attitudes towards overweight treatment; low self-assessment of skills in behavioral management strategies; low readiness to address overweight in children. |

| Motivational Interviewing Screening Tool to Address Pediatric Obesity (Hyde and McPeters, 2022) | 2022 | Pediatric clinic; Rural health clinic | Obesity | Assess impact of motivational interviewing survey tool to address obesity among patients ages 10 to 18 |

Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes; Process outcomes | 90 % of patients received motivational interviewing survey tool during well-child visit during project period. Over 50 % of patients classified as overweight/obese. |

| Sustainability of key Maine youth overweight collaborative improvements: A follow-up study (Polacsek et al., 2014) | 2014 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | Obesity | Evaluate intervention effects on provider knowledge, beliefs, practices, patient experience, and office systems | Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes | There was a significant increase in recording BMI percentile in charts from 2012 vs 2009, no change in recording of weight or blood pressure. Parent surveys indicate increase in counseling about sugar sweetened beverages and decrease in nutrition counseling. Clinician surveys report sustainment of knowledge, beliefs, practices. |

| The Health Care Provider’s Experience With Fathers of Overweight and Obese Children: A Qualitative Analysis (Anti et al., 2016) | 2016 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | Obesity | To examine the healthcare providers’ experiences working with fathers of overweight and obese children | Qualitative research | Exploratory outcomes (qualitative) | Providers reported fathers have less of a role or presence in child’s health compared to mother and are resistant to accepting child’s weight as an issue |

| Improving Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Use in an Integrated Health System: Impact of a Provider and Staff Intervention (McLean et al., 2017) | 2017 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | HPV vaccination | Test a multicomponent intervention to improve HPV vaccination in a regional healthcare system | Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes | HPV vaccination coverage increased from 41 to 59 % in intervention departments and only 32 to 45 % in control departments; however changes in series completion was not significantly different between intervention and control departments. |

| Human Papillomavirus Immunization in Rural Primary Care (Gunn et al., 2020) | 2020 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | HPV vaccination | Identify organizational and clinic factors that support HPV vaccine delivery | Mixed methods | Exploratory outcomes (qualitative); Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | Up-to-date vaccination rates ranged from 13 to 28 % for “low-performing clinics” and 50–70 % for “high-performing” clinics. Qualitative themes that emerged to distinguish higher performing clinics included: staffing and vaccine protocols, presence of a vaccine champion, utilizing all opportunities to vaccinate and patient communication and education. |

| HPV vaccine attitudes and practices among primary care providers in Appalachian Pennsylvania (Huey et al., 2009) | 2009 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice; Other: Gynecology practices | HPV vaccination | To understand primary care providers HPV vaccine-related practices and recommendations | Survey research | Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | In first survey; 80 % of clinicians were currently offering the vaccine; concerns about the vaccine included: cost and insurance, newness of the vaccine, worries that age was too young, not knowing who should administer vaccine. In second survey 94 % reported recommending to all patients and barriers to vaccination included cost of the vaccine (especially for women ages 18–26), belief that recommended age is too low and that vaccine may report sexual activity |

| Effect of provider prompts on adolescent immunization rates: a randomized trial (Szilagyi et al., 2015) | 2015 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | HPV vaccination | Assess impact of an electronic-health record based intervention on adolescent immunization rates | Randomized controlled trial | Intervention outcomes | No intervention effect was observed on increasing rates of HPV vaccination (any dose in the series). |

| Implementation Challenges and Opportunities Related to HPV Vaccination Quality Improvement in Primary Care Clinics in a Rural State (Askelson et al., 2019) | 2019 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | HPV vaccination | Understand selection and implementation of evidence-based interventions to support HPV vaccination | Survey research | Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | External actors (e.g., payors) are often involved in decision making about implementation of EBIs. Clinics use resources like the state health department, Vaccines for Children staff to support implementation efforts. |

| Evidence-Based Practice Model to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake: A Stepwise Approach (Beck et al., 2021) | 2021 | Other: Primary care/walk-in | HPV vaccination | Assess a stepwise evidence-based practice model to improve HPV vaccination uptake | Non-randomized experimental study | Intervention outcomes | 100 % of parents approached consented to vaccination. A total of 24 HPV vaccines were administered during the six-week intervention period, compared to 4 HPV vaccines in the six-week comparison period. |

| Sun protection counseling for children: primary care practice patterns and effect of an intervention on clinicians (Dietrich et al., 2000) | 2000 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice | Skin cancer | Describe implementation of SunSafe intervention in pediatric practices | Mixed methods | Intervention outcomes; Exploratory outcomes (qualitative); Exploratory outcomes (quantitative) | Intervention clinics increased their provision of educational materials in their waiting rooms and at summer well child visits and distributed more samples of sunscreen compared to control clinics. Pediatricians, compared to other types of providers, were more likely to address sun protection at visits and provide materials like educational pamphlets and sunscreen samples. |

| Prescription for health: changing primary care practice to foster healthy behaviors (Cifuentes et al., 2005) | 2005 | Pediatric clinic; Family practice; Other: Internal medicine | Multiple behaviors: Obesity; Smoking/vaping/ tobacco use | Describe lessons learned from a practice-based network project that addressed behavior change in the following areas: smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and risky alcohol use | Other: Observations; progress reports; meeting notes | Process outcomes | Four key lessons learned: health behavior counseling can be done by frontline staff in primary care practices; this counseling may require substantial practice redesign; refined of existing models and frameworks can guide these efforts; co-evolution, rather than traditional collaboration, can help create synergy across projects |

3.2. Barriers and facilitators to implementation

Across studies, we identified similarities in barriers and facilitators to implementing EBIs related to cancer prevention health topics in rural primary care settings. Below we outline these barriers and facilitators by CFIR domain (Table 3).

Table 3.

Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation, organized by CFIR domains.

| CFIR Domain | Levels | Barriers to implementation | Facilitators to implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outer setting | Community-level |

|

|

| Patient-level |

|

|

|

| Inner setting | Organization-level |

|

|

| Clinic-level |

|

|

|

| Characteristics of individuals | Clinician-level |

|

|

| Characteristics of the intervention | Intervention-level |

|

|

| Process | Implementation process | ---- |

|

3.3. Outer setting

3.3.1. Community-level

Several studies identified a lack of local, complimentary resources to support patients in the community as a barrier to implementation (Findholt et al., 2013, Shaikh et al., 2011); in some cases this was caused by cuts in funding to these services (Polacsek et al., 2014). As an example, in a qualitative study interviewing rural primary care physicians, participants reflected on the fact that there were no community resources (e.g., dietary counselors, child psychologists) available to support pediatric obesity interventions delivered in the primary care clinic (Findholt et al., 2013). On the other hand, several studies reported that availability of community-based resources were a facilitator (Shaikh et al., 2015, Thornberry et al., 2019). For example, in one study that explored current practices in obesity prevention, providers reported that they were able to make referrals to physical education in both schools and community center settings because of widespread community investment in these types of resources (Thornberry et al., 2019).

3.3.2. Patient-level

Many studies listed patient-level barriers to implementation, and in all cases, these were related to the family or parents/guardians, not the adolescent. Examples of these barriers were providers’ perception of lack of family engagement in child’s health or receptivity to change (Anti et al., 2016, Findholt et al., 2013, Shaikh et al., 2011, Wu et al., 2007) and low levels of willingness to participate in interventions (Anti et al., 2016, Hyde and McPeters, 2022). Beyond lack of engagement, other barriers included the possibility that parents may not trust clinicians and thus will not listen to their advice (Thornberry et al., 2019) or that the family’s lifestyle did not align with intervention goals. For example, in one study providers reported that the family’s eating habits were not aligned with the goals of an obesity-prevention intervention (Anti et al., 2016). In other studies, however, providers listed the high level of parents’ trust in clinicians as a facilitator to their efforts to implement an HPV vaccine promotion intervention (Beck et al., 2021).

3.4. Inner setting

3.4.1. Organization/system-level

Several studies reported on the undertaking of implementation efforts in networks of healthcare practices or the challenges of working within the confines of larger organizations. Several studies noted the lack of reimbursement for intervention activities as being a major barrier (e.g., no reimbursement for obesity screening) (Cifuentes et al., 2005, Gibson, 2016, Huey et al., 2009, Thornberry et al., 2019). While these higher-level organizational factors were often seen as barriers, some studies reported working within these systems could also facilitate implementation efforts. Two studies (one on HPV vaccination (Askelson et al., 2019) and one on obesity (Shaikh et al., 2015)) cited that their efforts were supported by strong internal alignment within organizations in terms of quality improvement priorities. Similarly, in two other studies on obesity prevention (Okihiro et al., 2013, Polacsek et al., 2014) a common facilitator was that higher level organizational actors recognized the importance of an intervention. In a study conducted in Maine, authors identified that implementation was helped by the fact that both major health systems in the state as well as local-level organizations aided in dissemination (Polacsek et al., 2014).

3.4.2. Clinic-level

Clinic-level factors were commonly reported across studies as both barriers and facilitators to implementation efforts. Common barriers were staffing shortages (Askelson et al., 2019, Findholt et al., 2013, Gunn et al., 2020) and not having enough time available to devote to implementation of interventions (Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Thornberry et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2007). For example, in one study detailing barriers to addressing childhood obesity, clinicians reported that competing priorities during both well-child and acute care visits meant that it was often difficult to fully address both the complex topic of obesity prevention and be able to provide counseling on diet and physical activity (Findholt et al., 2013). Other barriers included lack of infrastructure to support implementation (Beck et al., 2021, Cifuentes et al., 2005) and the fact that in some low-volume practices there were few opportunities to engage patients from target populations. However, these barriers were not universal, and in fact, in some studies infrastructure, specifically having strong electronic health record (EHR) systems, (Beck et al., 2021, Cifuentes et al., 2005, Gunn et al., 2020, Polacsek et al., 2014) were viewed as facilitating implementation efforts.

3.5. Characteristics of individuals

3.5.1. Clinician-level

In terms of individual-level or clinician factors affecting implementation, studies reported primarily on knowledge and personal beliefs. Over 20 % of studies reported that clinicians’ knowledge and/or a need for further training were barriers (Findholt et al., 2013, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Shaikh et al., 2011, Thornberry et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2007). As an example, in one study in rural Appalachia, almost 40 % of primary care providers self-reported low level of skill in using behavioral management strategies to address childhood obesity (Thornberry et al., 2019). Facilitators at this level included belief that the intervention, or specific components of the intervention, would be effective.

3.6. Characteristics of the intervention

3.6.1. Features of the intervention

Barriers identified included challenges of using intervention materials (Cifuentes et al., 2005, Dietrich et al., 2000) and technology related issues (San Giovanni et al., 2021). For example, in a study on a skin-cancer intervention, the educational materials required frequent restocking in the clinic so that they were available to patients (Dietrich et al., 2000). In a multi-site project aimed at addressing, among other issues, obesity and tobacco control, inconsistency in content and availability of patient-facing educational materials presented a barrier (Cifuentes et al., 2005). Other studies identified many facilitators related to characteristics of the intervention. Specifically, several cited that having materials that were easily accessible for patients support implementation efforts (San Giovanni et al., 2021, Shaikh et al., 2015, Shaikh et al., 2011, Dietrich et al., 2000).

3.7. Process

3.7.1. Implementation process

No barriers related to process were identified in these studies. In terms of facilitators, two studies, one on obesity (Shaikh et al., 2014) and one on HPV vaccination (Gunn et al., 2020), reported that having strong clinic champions was critical to the implementation process.

4. Discussion

We identified barriers and facilitators to implementation of EBIs to address adolescent cancer prevention in rural primary care settings in the United States in this scoping review. Across studies we found similarities in terms of these barriers and facilitators in each of the five CFIR domains: outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, characteristics of the intervention, and process. Barriers and facilitators were most commonly reported in the inner and outer setting, compared to the other three CFIR domains. While there is extensive research on these four adolescent health issues in general, there was a dearth of research related to rural primary care settings, especially on the topics of skin cancer and tobacco use. Given the higher rates in rural populations of cancer risk factors related to sun exposure (Nagelhout et al., 2019) and tobacco (Pesko and Robarts, 2017), our results identify a need to better understand how to implement EBIs to address these risk factors in rural primary care settings. At a basic level, this indicates a need for increased research, and likely increased funding, to address these topics in rural primary care. However, this lack of literature could also point to broader issues affecting rural settings. Interventions are often developed in large urban and well-resourced clinical settings and thus implementation requires adaptation and tailoring to be appropriate for rural clinics (Smith et al., 2016). Moreover, implementing new EBIs is time consuming and requires resources; rural clinics often struggle with staffing vacancies leaving little staff time for implementation (Wright et al., 2015). This was a barrier identified in several studies included in this review (Askelson et al., 2019, Gunn et al., 2020).

Beyond identifying areas for future research, we identified common implementation barriers that may be particularly relevant in rural primary care settings and could be addressed in the short-term. Priority should be given to what is actionable and potentially high-impact. For example, two commonly identified barriers were limited clinician knowledge (Findholt et al., 2013, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Shaikh et al., 2011, Thornberry et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2007) and lack of reimbursement for intervention-related care (Cifuentes et al., 2005, Gibson, 2016, Huey et al., 2009, Thornberry et al., 2019). While changing the process for reimbursement requires action at higher organizational or even policy-levels, addressing clinician knowledge may be a more immediately manageable task. Programs like Project ECHO, a virtual community of practices utilizing a “hub” and “spoke” model wherein rural clinics are connected with mentors at academic medical centers (Arora et al., 2018) could be used to focus specifically on implementing EBIs to address provider knowledge. Rural clinicians will also benefit from the digitization of continuing medical education that has accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sibley, 2022), allowing them easier access to continuing medical education credits and opportunities for learning.

Leveraging factors identified as facilitators in these efforts is equally important. Most of the facilitators identified were classified in the inner and outer setting domains. Assessing and leveraging facilitators is an implementation strategy (Powell et al., 2015); and can be a precursor to implementation projects. Going through this kind of process could help clinics with limited time or capacity to better select and implement interventions by taking advantage of their existing strengths. For example, in several studies the existence of workflows (Beck et al., 2021, Cifuentes et al., 2005, Shaikh et al., 2015) or technology systems like EHRs being in place (Beck et al., 2021, Cifuentes et al., 2005, Gunn et al., 2020, Polacsek et al., 2014) were identified as facilitators. Selecting interventions that rely on these kinds of systems, for example integrating EHR alerts about obesity, tobacco, or sun exposure counseling at well-child visits, may be more efficient than trying to implement something that does not already have the infrastructure in place.

Finally, when comparing across health topics, we identified several commonalities between barriers and facilitators for implementation, especially for HPV and obesity. Given limited resources in rural settings, it may be beneficial to identify strategies that could support implementation of EBIs to address multiple topics. For example, using motivational interviewing with parents has been suggested as a strategy to address both obesity counseling (Pakpour et al., 2015) and HPV vaccine hesitancy (Reno et al., 2018). Designing more general motivational interviewing trainings for health care providers that focus on overall skills and application to multiple health topics, rather than one specific topic, could help support future efforts to implementation efforts. Moreover, given that providers’ perceived a lack of parental engagement as a barrier in many studies (Anti et al., 2016, Hyde and McPeters, 2022), interventions to engage parents and build rapport and trust between families and clinicians may be warranted. This is particularly relevant given the increasing literature on the role of trust in parent-clinician relationships in relation to HPV vaccination (Glanz et al., 2013) and obesity (Lupi et al., 2014).

Another common facilitator was having clinic champions for implementation efforts (Gunn et al., 2020, Shaikh et al., 2014). Pinpointing who in rural primary care clinics is best positioned to be a clinic champion and integrating this as a strategy into future efforts can support implementation of EBIs in all areas. There is evidence that middle managers (e.g., nurse managers, clinic managers), or individuals who oversee day-to-day activity but also report to higher level organizational leadership, may be particularly well-positioned to serve in this role in rural primary care settings (Ryan et al., 2023). Integrating these kinds of strategies to improve overall implementation capacity or to address multiple health topics is especially important in rural primary care clinics that may have fewer resources or staffing capacity overall.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our scoping review had several strengths and limitations to note in interpreting our findings. In terms of strengths, our use of the JBI scoping review protocol provided a systematic way to assess and explore the literature. Moreover, at each step, at least two team members of our multidisciplinary team participated in the process from screening through abstraction, enhancing the validity and reproducibility of our results. The primary limitation to note is in relation to our inclusion and exclusion criteria. We only included peer-reviewed, full-length papers; therefore, it is possible that conference proceedings or grey literature may exist on this topic but was not included in this review. Additionally, we believe it is a limitation that only four of the included studies reported on how they defined rurality. Prior literature has determined that depending on the rural definition used, outcomes may be different (Long et al., 2021), thus without knowing which definitions were used in the studies in this review, our ability to compare across studies is limited.

5. Conclusions

Adolescence is a critical time for preventing future cancers, with pediatric clinicians serving rural adolescents being well-positioned to reduce cancer risk through HPV vaccination and interventions to address tobacco use, obesity, and sun exposure. In our scoping review we found relatively few studies, especially on tobacco and sun exposure, that explored implementation of evidence-based interventions related to these key topics in rural primary care settings in the United States. In the studies we reviewed we identified multi-level barriers and facilitators to implementation efforts using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to classify these factors. In the near term, prioritizing what is actionable at the clinic-level to address barriers and leverage facilitators is likely to be most impactful. Longer term priorities in this area should include further research and increased funding to support EBI adaptation and implementation in rural clinics to reduce urban–rural cancer inequities.

Funding

This study was supported by the following NCI Grant #T32 CA172009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Grant # U48DP006381. MG is supported by NHLBI Grant # F31HL164126. Funders had no role in the design, conduct of this study, or decision to submit for publication. This study does not represent the views of the funder.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Grace W. Ryan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Paula Whitmire: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Annabelle Batten: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Melissa Goulding: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Becky Baltich Nelson: Methodology, Software, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Stephenie C. Lemon: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Lori Pbert: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102449.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Anti E., Laurent J.S., Tompkins C. The Health Care Provider's Experience With Fathers of Overweight and Obese Children: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Pediatric Health Care. 2016;30(2):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris E, Munn Z. Chapter 1: JBI Systematic Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-02.

- Arora S, Kalishman SG, Thornton KA, et al. Project ECHO: A Telementoring Network Model for Continuing Professional Development [published correction appears in J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2018 Winter;38(1):78]. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(4):239-244. doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Askelson N.M., Ryan G., Seegmiller L., Pieper F., Kintigh B., Callaghan D. Implementation Challenges and Opportunities Related to HPV Vaccination Quality Improvement in Primary Care Clinics in a Rural State. J. Community Health. 2019;44(4):790–795. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00676-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A., Bianchi A., Showalter D. Evidence-Based Practice Model to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake: A Stepwise Approach. Nurs. Womens Health. 2021;25(6):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro, FM, Wolff MS. Puberty as a window of susceptibility. J. Russo (Ed.), Environment and Breast Cancer, Springer, New York (2011), pp. 29-41.

- Calle E.E., Rodriguez C., Walker-Thurmond K., Thun M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(17):1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes M., Fernald D.H., Green L.A., et al. Prescription for health: changing primary care practice to foster healthy behaviors. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005;3(Suppl 2):S4–S11. doi: 10.1370/afm.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D.J., Dorr D.A., Knierim K., et al. Primary Care Practices' Abilities And Challenges In Using Electronic Health Record Data For Quality Improvement. Health Aff. (millwood) 2018;37(4):635–643. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. Published 2009 Aug 7. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dietrich A.J., Olson A.L., Sox C.H., Winchell C.W., Grant-Petersson J., Collison D.W. Sun protection counseling for children: primary care practice patterns and effect of an intervention on clinicians. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000;9(2):155–159. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagnan L.J., Ramsey K., Dickinson C., Kline T., Parchman M.L. Place Matters: Closing the Gap on Rural Primary Care Quality Improvement Capacity-the Healthy Hearts Northwest Study. J. Am. Board Family Med. 2021;34(4):753–761. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.04.210011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findholt N.E., Davis M.M., Michael Y.L. Perceived barriers, resources, and training needs of rural primary care providers relevant to the management of childhood obesity. J. Rural Health. 2013;29(Suppl 1):s17–s24. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuemmeler B.F., Pendzich M.K., Tercyak K.P. Weight, dietary behavior, and physical activity in childhood and adolescence: implications for adult cancer risk. Obes. Facts. 2009;2(3):179–186. doi: 10.1159/000220605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt J.M., Dodd S., Walling E., Lee A.A., Kulka K., Lobb R. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination in primary care practices: a mixed methods study using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018;19(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0750-5. Published 2018 May 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson S.J. Translation of clinical practice guidelines for childhood obesity prevention in primary care mobilizes a rural Midwest community. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2016;28(3):130–137. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz J.M., Wagner N.M., Narwaney K.J., et al. A mixed methods study of parental vaccine decision making and parent-provider trust. Acad. Pediatrics. 2013;13(5):481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker S.L., Polacsek M., Letourneau L., et al. Evaluation of a primary care intervention on body mass index: the Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative. Child. Obes. 2015;11(2):187–193. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn R., Ferrara L.K., Dickinson C., et al. Human Papillomavirus Immunization in Rural Primary Care. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020;59(3):377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey N.L., Clark A.D., Kluhsman B.C., Lengerich E.J. ACTION Health Cancer Task Force. HPV vaccine attitudes and practices among primary care providers in Appalachian Pennsylvania. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2009;6(2):A49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde H., McPeters S.L. Motivational interviewing screening tool to address pediatric obesity. J. Nurse Pract. 2022;18(3):289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadu M.K., Stolee P. Facilitators and barriers of implementing the chronic care model in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015;16:12. doi: 10.1186/s12875-014-0219-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.S., Eder M., Weinmann S., et al. Rockville, MD; 2011. Behavioral Counseling to Prevent Skin Cancer: Systematic Evidence Review to Update the 2003 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linos E., Willett W.C., Cho E. Red meat consumption during adolescence among premenopausal women and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2146–2151. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J.C., Delamater P.L., Holmes G.M. Which Definition of Rurality Should I Use?: The Relative Performance of 8 Federal Rural Definitions in Identifying Rural-Urban Disparities. Med. Care. 2021;59(Suppl 5):S413–S419. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundeen EA, Park S, Pan L, O'Toole T, Matthews K, Blanck HM. Obesity Prevalence Among Adults Living in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Counties - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(23):653-658. Published 2018 Jun 15. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6723a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lupi J.L., Haddad M.B., Gazmararian J.A., Rask K.J. Parental perceptions of family and pediatrician roles in childhood weight management. J. Pediatrics. 2014;165(1):99–103.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung NM, Gargano JW, Park IU, et al. Estimated Number of Cases of High-Grade Cervical Lesions Diagnosed Among Women - United States, 2008 and 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(15):337-343. Published 2019 Apr 19. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McLean H.Q., VanWormer J.J., Chow B.D.W., et al. Improving Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Use in an Integrated Health System: Impact of a Provider and Staff Intervention. J. Adolesc. Health. 2017;61(2):252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-Dose Schedule for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination - Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(49):1405-1408. Published 2016 Dec 16. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nagelhout E.S., Parsons B.G., Haaland B., et al. Differences in reported sun protection practices, skin cancer knowledge, and perceived risk for skin cancer between rural and urban high school students. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(11):1251–1258. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI), President's Cancer Panel. Reducing environmental cancer risk: What we can do now: 2008-2009 Annual Report NCI, Washington, DC (2010).

- Okihiro M., Pillen M., Ancog C., Inda C., Sehgal V. Implementing the obesity care model at a community health center in Hawaii to address childhood obesity. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2 Suppl):1–11. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakpour A.H., Gellert P., Dombrowski S.U., Fridlund B. Motivational interviewing with parents for obesity: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e644–e652. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Medina D., Mojica C., Liang Y., Ouyang Y., Ramos A.I., Gomez I. Promoting Weight Maintenance among Overweight and Obese Hispanic Children in a Rural Practice. Child. Obes. 2015;11(4):355–363. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesko M.F., Robarts A.M.T. Adolescent Tobacco Use in Urban Versus Rural Areas of the United States: The Influence of Tobacco Control Policy Environments. J. Adolesc. Health. 2017;61(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13-17 Years - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(35):1183-1190. Published 2021 Sep 3. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7035a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Polacsek M., Orr J., Letourneau L., et al. Impact of a primary care intervention on physician practice and patient and family behavior: keep ME Healthy–-the Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative. Pediatrics. 2009;123(Suppl 5):S258–S266. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2780C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacsek M., Orr J., O'Brien L.M., Rogers V.W., Fanburg J., Gortmaker S.L. Sustainability of key Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative improvements: a follow-up study. Child. Obes. 2014;10(4):326–333. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B.J., Waltz T.J., Chinman M.J., et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. Published 2015 Feb 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, Fields A. “Defining rural at the U.S. Census Bureau.” ACSGEO-1, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2016.

- Reno J.E., O'Leary S., Garrett K., et al. Improving Provider Communication about HPV Vaccines for Vaccine-Hesitant Parents Through the Use of Motivational Interviewing. J. Health Commun. 2018;23(4):313–320. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1442530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Charlton ME, Scherer AM, et al. Understanding Implementation of Evidence-Based Interventions to Address Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Qualitative Perspectives of Middle Managers [published online ahead of print, 2023 Feb 10]. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2023;99228231154661. doi:10.1177/00099228231154661. [DOI] [PubMed]

- San Giovanni C.B., Dawley E., Pope C., Steffen M., Roberts J. The Doctor Will “Friend” You Now: A Qualitative Study on Adolescents' Preferences for Weight Management App Features. South. Med. J. 2021;114(7):373–379. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli J.S., Sivaramakrishnan K., Edelstein Z.R., Fried L.P. Adolescent risk-taking, cancer risk, and life course approaches to prevention. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013;52(5 Suppl):S41–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh U., Nettiksimmons J., Romano P. Pediatric obesity management in rural clinics in California and the role of telehealth in distance education. J. Rural Health. 2011;27(3):263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh U., Nettiksimmons J., Joseph J.G., Tancredi D., Romano P.S. Collaborative practice improvement for childhood obesity in rural clinics: the Healthy Eating Active Living Telehealth Community of Practice (HEALTH COP) Am. J. Med. Qual. 2014;29(6):467–475. doi: 10.1177/1062860613506252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh U., Romano P., Paterniti D.A. Organizing for Quality Improvement in Health Care: An Example From Childhood Obesity Prevention. Qual. Manag. Health Care. 2015;24(3):121–128. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley J.B. Meeting the Future: How CME Portfolios Must Change in the Post-COVID Era. J Eur CME. 2022;11(1):2058452. doi: 10.1080/21614083.2022.2058452. Published 2022 Apr 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg M., Carter-Edwards L., Murphy G., et al. Treating pediatric obesity in the primary care setting to prevent chronic disease: perceptions and knowledge of providers and staff. N. C. Med. J. 2012;73(1):9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.A., Adimu T.F., Martinez A.P., Minyard K. Selecting, Adapting, and Implementing Evidence-based Interventions in Rural Settings: An Analysis of 70 Community Examples. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4A):181–193. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi P.G., Serwint J.R., Humiston S.G., et al. Effect of provider prompts on adolescent immunization rates: a randomized trial. Acad. Pediatrics. 2015;15(2):149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry T.S., Jr, Bodziony V.R., Gross D.A. Provider Practice and Perceptions of Pediatric Obesity in Appalachian Kentucky. South. Med. J. 2019;112(11):553–559. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012 [accessed 2019 Feb 28].

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman D.C., Bibbins-Domingo K., et al. Screening for Obesity in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2017;317(23):2417–2426. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman D.C., Curry S.J., et al. Behavioral Counseling to Prevent Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018;319(11):1134–1142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Owens D.K., Davidson K.W., et al. Primary Care Interventions for Prevention and Cessation of Tobacco Use in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323(16):1590–1598. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson M., Saraiya M., Ahmed F., et al. Using population-based cancer registry data to assess the burden of human papillomavirus-associated cancers in the United States: overview of methods. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2841–2854. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weihe P., Spielmann J., Kielstein H., Henning-Klusmann J., Weihrauch-Blüher S. Childhood Obesity and Cancer Risk in Adulthood. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020;9(3):204–212. doi: 10.1007/s13679-020-00387-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright B., Damiano P.C., Bentler S.E. Implementation of the Affordable Care Act and rural health clinic capacity in Iowa. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 2015;6(1):61–65. doi: 10.1177/2150131914542613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Tudiver F., Wilson J.L., Velasco J. Child overweight interventions in rural primary care practice: a survey of primary care providers in southern Appalachia. South. Med. J. 2007;100(11):1099–1104. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181583949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahnd W.E., James A.S., Jenkins W.D., et al. Rural-Urban Differences in Cancer Incidence and Trends in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018;27(11):1265–1274. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.