Abstract

Virginiae butanolides (VBs), which are among the butyrolactone autoregulators of Streptomyces species, act as a primary signal in Streptomyces virginiae to trigger virginiamycin biosynthesis and possess a specific binding protein, BarA. To clarify the in vivo function of BarA in the VB-mediated signal pathway that leads to virginiamycin biosynthesis, two barA mutant strains (strains NH1 and NH2) were created by homologous recombination. In strain NH1, an internal 99-bp EcoT14I fragment of barA was deleted, resulting in an in-frame deletion of 33 amino acid residues, including the second helix of the probable helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif. With the same growth rate as wild-type S. virginiae on both solid and liquid media, strain NH1 showed no apparent changes in its morphological behavior, indicating that the VB-BarA pathway does not participate in morphological control in S. virginiae. In contrast, virginiamycin production started 6 h earlier in strain NH1 than in the wild-type strain, demonstrating for the first time that BarA is actively engaged in the control of virginiamycin production and implying that BarA acts as a repressor in virginiamycin biosynthesis. In strain NH2, an internal EcoNI-SmaI fragment of barA was replaced with a divergently oriented neomycin resistance gene cassette, resulting in the C-terminally truncated BarA retaining the intact helix-turn-helix motif. In strain NH2 and in a plasmid-integrated strain containing both intact and mutated barA genes, virginiamycin production was abolished irrespective of the presence of VB, suggesting that the mutated BarA retaining the intact DNA-binding motif was dominant over the wild-type BarA. These results further support the hypothesis that BarA works as a repressor in virginiamycin production and suggests that the helix-turn-helix motif is essential to its function. In strain NH1, VB production was also abolished, thus indicating that BarA is a pleiotropic regulatory protein controlling not only virginiamycin production but also autoregulator biosynthesis.

Streptomycetes are gram-positive bacteria characterized by their versatile ability to produce secondary metabolites and by their morphological complexity (1, 6). Both or either of these phenotypes are controlled in some Streptomyces species by low-molecular-weight compounds called butyrolactone autoregulators (24), and the 10 butyrolactone autoregulators isolated to date have been classified into three types according to structural differences in their C-2 side chains: (i) the virginiae butanolide (VB) type possesses a 6-α-hydroxy group, as exemplified by VB-A∼E of Streptomyces virginiae (3, 14, 22, 27, 28), which controls virginiamycin production; (ii) the IM-2 type possesses a 6-β-hydroxy group, as exemplified by IM-2 of Streptomyces sp. strain FRI-5 (17, 24, 30), which controls the production of a blue pigment and nucleoside antibiotics; and (iii) the A-factor type possesses a 6-keto group, as exemplified by A-factor of Streptomyces griseus (8, 13, 18). Although the structural differences among these autoregulators are small, producer strains show a high degree of ligand specificity toward the corresponding autoregulator type, indicating the presence of receptor proteins of strict ligand specificity (5, 16, 20).

The VB-specific binding protein (BarA) of S. virginiae was purified, and the gene encoding it (barA) was cloned and characterized in our laboratory (21). The N-terminal region of BarA has been predicted to form a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif, and in vitro analyses using recombinant BarA have revealed that BarA binds to specific DNA sequences in the absence of VB and dissociates from the DNA by binding with VB (12), suggesting that BarA should function as a transcriptional regulator, the DNA-binding activity of which is controlled by VB. Although BarA was the only logical candidate as the mediator of VB signal because we detected no other VB binding protein during the purification of BarA, it was less clear whether the VB-BarA pathway was actually involved in the control of virginiamycin production.

In this study, to assess the in vivo function of BarA, two kinds of barA mutants were constructed by homologous recombination between the wild-type barA gene on the chromosome and the mutated barA gene on a plasmid. Phenotypic and biochemical analyses of the mutants provided the first in vivo evidence that the VB-BarA pathway participates not only in virginiamycin production but also in autoregulator biosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

S. virginiae (strain MAFF 10-06014; National Food Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Tukuba, Japan) was grown at 28°C as described previously (10, 28). For genetic manipulation in Escherichia coli and Streptomyces, E. coli DH5α (4) and Streptomyces lividans TK21 (7) were used. Streptomyces strains were grown at 28°C in yeast extract-malt extract (YEME) liquid medium for preparation of protoplasts (7), in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) for preparation of total DNA, and on ISP no. 2 (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) for spore formation. S. lividans TK21 was obtained from D. A. Hopwood (John Innes Centre, Norwich, United Kingdom).

pUC19 was used for genetic manipulation in E. coli. pFDNEO-S (2), containing a modified neomycin resistance gene (neo) from transposon Tn5, was used as a source of resistance marker for constructing a barA mutant strain, NH2. pGM12 is a derivative of E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector pGM160 (19). By propagating pGM160 in S. lividans TK21, spontaneous deletion of the plasmid portion that encodes replication in E. coli occurred, resulting in pGM12 that can replicate in Streptomyces but not in E. coli.

Chemicals.

All chemicals were of reagent or high-performance liquid chromatography grade and were purchased from either Nacalai Tesque (Osaka, Japan), Takara Shuzo (Shiga, Japan) or Wako Pure Chemical Industrial (Osaka, Japan). Virginiamycin M1 and S were purified as described previously (15). Authentic VB was synthesized as described previously (20).

Construction of vectors for gene replacement.

A 6.2-kbp PstI fragment (12) ranging from 3.4 kbp upstream to 2.1 kbp downstream of barA was subcloned into pUC18 to generate pBA1 (see Fig. 1A). To delete an internal 99-bp EcoT14I fragment encoding from Lys51 to Ser83 of BarA, pBA1 was digested with XbaI and EcoT14I and then a 2.8-kbp EcoT14I fragment containing the upstream fragment and the 5′ 154-bp fragment of the barA coding sequence was inserted. The construct was confirmed to have the desired deletion by DNA sequencing. From the resulting plasmid, the EcoRI-HindIII fragment was subcloned into the EcoRI-HindIII-digested pIJ486 (26) to generate pBAD22. The plasmid pBAD22 was used to generate a barA mutant strain, NH1.

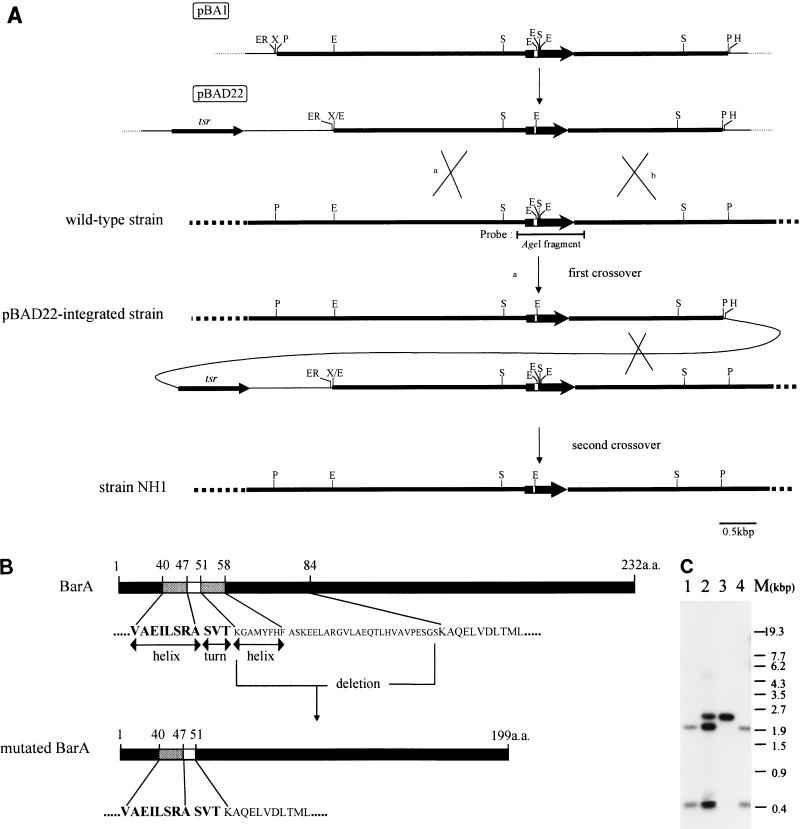

FIG. 1.

Gene replacement of S. virginiae barA gene with mutated barA by homologous recombination. (A) Restriction maps of pBAD22 and the chromosomal barA region of wild-type S. virginiae and of the pBAD22-integrated strain and barA mutant strain NH1. A single crossover between pBAD22 and a homologous DNA in the chromosome (such as via route a) gave the pBAD22-integrated strain. A loss of the plasmid sequence by the second crossover generated strain NH1. Filled bars represent regions from S. virginiae DNA. Thick arrows indicate the location and orientation of barA, and open bars represent the estimated helix-turn-helix motif inside barA. tsr is the thiostrepton resistance gene. Abbreviations: ER, EcoRI; E, EcoT14I; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SacII; X, XbaI. (B) Schematic representation of wild-type BarA and the mutated BarA of strain NH1. Filled bars indicate the barA coding region. Amino acid residues for the estimated helix-turn-helix motif and those encoded by the 99-bp EcoT14I fragment (small capitals) are shown below the filled bars. The numbers above the filled bars indicate the total number of amino acid residues (a.a.) for the wild-type BarA and mutated BarA. (C) Hybridization pattern of DNA. SacII-digested total DNAs from the S. virginiae wild-type strain (lane 1), pBAD22-integrated strain (lane 2), barA mutant strain NH1 (lane 3), and wild-type segregant (lane 4) were used. A 0.9-kbp AgeI fragment containing the barA gene was used as a probe. A single 2.4-kbp SacII band, rather than two SacII bands (0.5 and 2.0 kbp), was detected in strain NH1, because of the deletion of the EcoT14I fragment containing a SacII site. M, marker DNAs.

A 2.8-kbp BamHI fragment containing the barA gene (21) was subcloned into the BamHI site of modified pUC19, the SmaI site of which was deleted previously (pBA2 [see Fig. 4A]). An internal 98-bp EcoNI-SmaI fragment of barA was replaced with a blunt-ended SalI fragment (1.0 kbp) containing a modified neo gene from pFDNEO-S. The resulting BamHI fragment containing the mutated barA was subcloned into the BamHI site of pGM12 to generate pGM122. The plasmid pGM122 was used to construct a barA mutant strain, NH2.

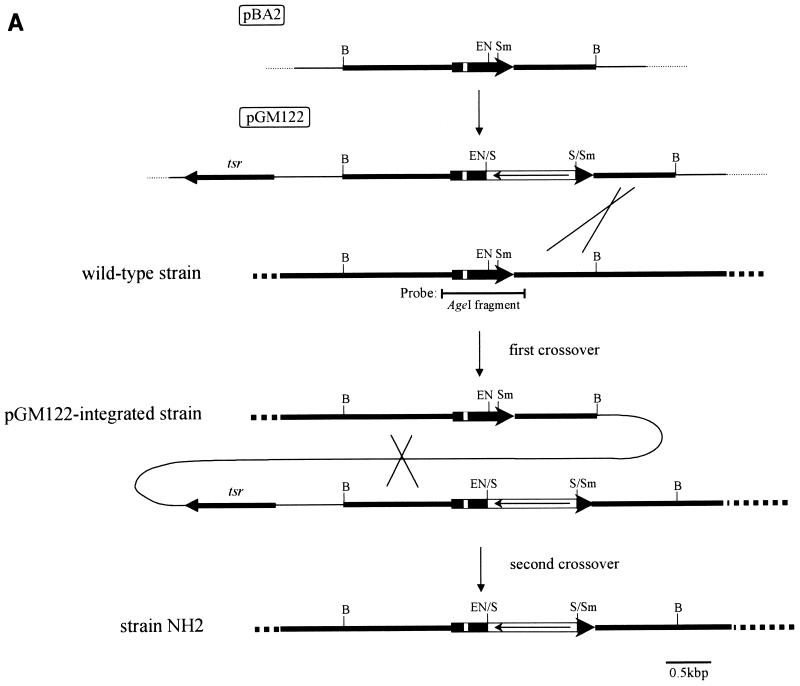

FIG. 4.

Gene replacement of S. virginiae barA gene with mutated barA by homologous recombination. (A) Restriction maps of pGM122 and the chromosomal barA region of wild-type S. virginiae and of the pGM122-integrated strain and barA mutant strain NH2. A single crossover between pGM122 and a homologous DNA in the chromosome gave the pGM122-integrated strain. A loss of the plasmid sequence by the second crossover generated strain NH2. Filled bars represent regions from S. virginiae DNA. Thick arrows indicate the location and orientation of barA, and open bars represent the estimated helix-turn-helix motif inside barA. Open bars containing an arrow indicate the location and orientation of the neomycin resistance gene. tsr is the thiostrepton resistance gene. Abbreviations: B, BamHI; EN, EcoNI; S, SalI; Sm, SmaI. (B) Hybridization pattern of DNA. BamHI-digested total DNAs from the S. virginiae wild-type strain (lane 1), pGM122-integrated strain (lane 2), barA mutant strain NH2 (lane 3), and wild-type segregant (lane 4) were used. The AgeI fragment containing the barA gene was used as a probe. M, marker DNAs.

DNA manipulation.

DNA manipulations in E. coli and Streptomyces were performed by the methods of Sambrook et al. (23) and Hopwood et al. (7), respectively. Protoplast formation and transformation of S. virginiae were performed by the methods of Kawachi et al. (9).

Southern blot analysis.

Three micrograms of digested DNA were loaded on each lane, electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, and transferred to Hybond-N+ (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Membranes were prehybridized for 1 h at 65°C and hybridized for 18 h. The probe used was a 0.9-kbp AgeI fragment containing the barA gene and labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a Random Primer DNA Labeling Kit, version 2 (Takara Shuzo). Membranes were then washed thoroughly in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC consists of 0.015 M sodium citrate and 0.15 M NaCl [pH 7.7]) containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 65°C. Autoradiography was performed by using Kodak X-Omat films at −80°C, with intensifying screens, for 1 to 5 h.

Western blot analysis.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed on 10 to 20% polyacrylamide precast gradient gels (Daiichi Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan). Crude extracts containing 50 μg of protein were loaded. After transfer to an Immobilon-PSQ transfer membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), the proteins were immunodetected with rabbit antiserum raised against the recombinant BarA protein expressed in E. coli (21), using an enhanced chemiluminescense (ECL) kit from Amersham according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Marker proteins for SDS-PAGE were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). Densitometric analysis was performed with a Shimadzu densitometer (model CS-9300PC).

Determination of VB and virginiamycin.

The amounts of virginiamycins produced were determined by a bioassay using Bacillus subtilis PCI219 as an indicator strain (29). Virginiamycin is a mixture of two chemically different compounds, virginiamycins M1 and S, showing synergistic antibiotic activity. Because the ratio between them will affect apparent antibiotic activity, we also analyzed the ratio between virginiamycins M1 and S by C18 reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously (25) and confirmed that the ratio was unchanged for strain NH1 and the wild-type strain.

The amount of VB in liquid cultures of S. virginiae was determined by measuring the VB-dependent production of virginiamycin (20). One unit of VB activity is the minimum amount required for induction of virginiamycin production and corresponded to 0.6 ng (2.6 nM) of VB-A per ml (28).

VB binding assay.

VB binding activity was routinely assayed by the ammonium sulfate precipitation method (11) with [3H]VB-C7 (54.6 Ci/mmol) in the presence and absence of 2,000-fold cold VB-C6.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of barA mutant strain NH1.

To determine the in vivo function of BarA in S. virginiae, wild-type barA in the chromosome was replaced with a mutated barA by using pBAD22 (Fig. 1A). The modified barA gene on pBAD22 (for details, see Materials and Methods) lost a 99-bp EcoT14I fragment, which resulted in the in-frame deletion of 33 amino acid residues containing the second helix region of the estimated helix-turn-helix motif (Fig. 1B). After S. virginiae MAFF 10-06014 was transformed using pBAD22, pBAD22-integrated strains from the first crossover, as by route a in Fig. 1A, were selected among thiostrepton-resistant transformants. After single colony isolation in the presence of thiostrepton (5 μg/ml), Southern blot hybridization was performed to confirm the integration of pBAD22 (Fig. 1C, lane 2), and no plasmid form of pBAD22 was detected (data not shown). To facilitate the second crossover, the plasmid-integrated strain was put through two rounds of cultivation on liquid TSB medium lacking thiostrepton. As expected, two types of thiostrepton-sensitive colonies were obtained: namely, barA mutants (in which the wild-type barA gene was replaced with the altered sequence) and regenerated wild-type strains (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 and 4). One of these mutants, designated strain NH1, was used for further investigation.

The growth characteristics of strain NH1 on several agar plates were indistinguishable from those of the wild-type strain, suggesting that BarA does not participate in the control of morphological differentiation in S. virginiae. This agrees well with the fact that the addition of VB does not influence the morphology of S. virginiae on agar plates (unpublished data).

Polypeptides encoded by mutated barA in strain NH1.

To confirm that the mutated barA gene was expressed in strain NH1, we performed a Western blot analysis with an antibody raised against recombinant BarA (Fig. 2). A protein band of 25 kDa was detected in strain NH1 (Fig. 2, lanes 3 to 6). Although the detected band had a lower electrophoretic mobility than the molecular mass (21.5 kDa) predicted from the DNA sequence, it was concluded to be the mutated BarA protein, because BarA protein tends to migrate more slowly on SDS-PAGE than its actual molecular mass (21), as evident from the behavior of wild-type BarA (lanes 1 and 2, apparent molecular mass, 28 kDa; actual molecular mass, 25.0 kDa).

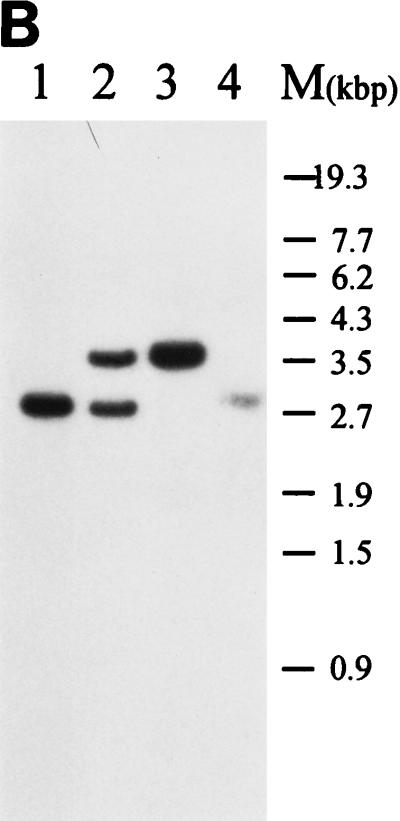

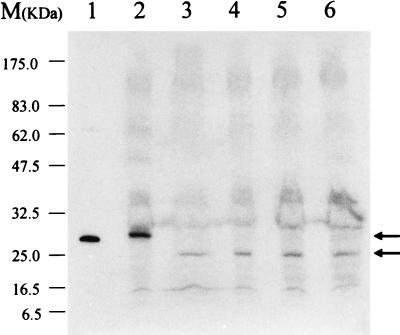

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of the mutated BarA protein from strain NH1. Crude cell extracts containing 50 μg of protein were loaded and analyzed by anti-BarA antibody. Lane 1, purified recombinant BarA from E. coli; lane 2, wild-type strain harvested after 12 h of cultivation; lanes 3 to 6, strain NH1 harvested at 6, 8, 10, and 12 h of cultivation. The top arrow to the right of the gel indicates the position of wild-type BarA, and the bottom arrow indicates the position of mutated BarA.

The mutated BarA appeared from the early growth phase, which was identical to the case of native BarA in wild-type S. virginiae (12). However, as judged from the band intensities, the cellular level (about 16 to 20%) of the mutated BarA was very low compared to the level of wild-type BarA. Although the lower signal may reflect the low reactivity of the antibody used, it is unlikely because our polyclonal antibody preferentially recognizes the C-terminal half of BarA (unpublished data). The actual reason for the low expression of mutated BarA is not clear at present but would seem to reflect the instability of the transcript or the low efficiency of translation rather than the degradation of the mutated BarA protein, since only few degradation products were detected by anti-BarA antibody.

Several phenotypes of the strain NH1.

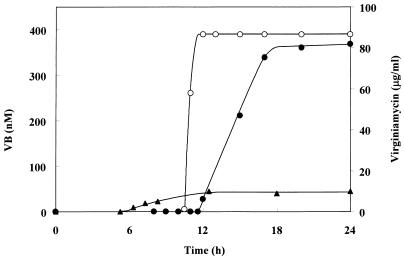

Virginiamycin production by strain NH1 was examined by bioassay using B. subtilis (Fig. 3). While a wild-type segregant as well as the wild-type parental strain began to produce virginiamycin after 12 h of cultivation, virginiamycin production by strain NH1 began much earlier (6 h of cultivation), suggesting that the BarA protein acts as repressor in virginiamycin production. No difference in growth was observed between the NH1 strain and the wild-type strain (data not shown). In the wild-type strain, it has been shown that artificial addition of VB at various times prior to the natural production of VB (after 4 to 10 h of cultivation) induces earlier production of virginiamycin (31). Therefore, it is conceivable that repression by native BarA is released by VB binding, which would lead to virginiamycin production in the wild-type strain, while the mutated BarA could not exert repression either due to the lack of helix-turn-helix motif or the small amount of protein. Virginiamycin is a mixture of two chemically distinct compounds, virginiamycins M1 and S, showing strong synergistic antibiotic activity. Because the two components were produced by strain NH1 with the same ratio to that by the wild-type strain (data not shown), BarA can be concluded to coordinately control the two biosynthesis pathways. However, the amount of virginiamycin produced by strain NH1 was about 10% of that produced by the wild-type strain, which agreed well with our previous observation that VB addition at the beginning of cultivation reduced virginiamycin production to the same extent in the wild-type strain (31). Therefore, it seems that derepression or lack of repression by BarA from the beginning of cultivation caused a lower production of virginiamycin, although the underlying mechanism requires further study.

FIG. 3.

Time course of virginiamycin production in two strains of S. virginiae. Wild-type S. virginiae (•) and barA mutant strain NH1 (▴) were studied. The amount of VB produced by the wild-type strain is also shown (○). Strain NH1 did not produce any VB.

VB production was examined to determine whether the barA mutation affects VB biosynthesis (Table 1). Surprisingly, strain NH1 did not produce any VB during cultivation for up to 24 h, while the wild-type segregant and the wild-type strain produced similar amounts of VB, implying that no mutation relating to VB biosynthesis other than barA was generated during the recombination event. These results indicate that BarA should also participate in VB biosynthesis. This result will be discussed later.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes of strains NH1 and NH2

| Strain | Amt (μg/ml) of virginiamycin produceda | VB binding activ- ityb (pmol/mg of protein) | Amt (nM) of VB producedc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 86 | 0.44 | 390 |

| NH1 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| pGM122-integrated | 0 | 0.14 | NT |

| NH2 | 0 | 0 | 364 |

Virginiamycin production was determined after 24 h of cultivation.

VB binding activity was determined after 12 h of cultivation.

VB production was tested after 24 h of cultivation. NT, not tested.

Construction of barA mutant strain NH2.

We constructed another type of barA mutant by using pGM122 (for details, see Materials and Methods) in which a 1.0-kbp neomycin resistance gene was inserted 239 bp downstream of the helix-turn-helix motif of barA (Fig. 4A). As in the case of strain NH1, a pGM122-integrated strain derived from the first crossover was selected from the colonies resistant to both neomycin (200 μg/ml) and thiostrepton (5 μg/ml). After cultivating the plasmid-integrated strain for two rounds on liquid TSB medium plus only neomycin (200 μg/ml), we selected colonies that were both neomycin resistant and thiostrepton sensitive to obtain barA mutants derived from the second crossover. Wild-type segregants were obtained by cultivating the plasmid-integrated strain in the absence of antibiotics and selecting the neomycin-thiostrepton-sensitive strains. The genomic structure of the representative strains from each crossover step was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization (Fig. 4B), and one of the neomycin-resistant, thiostrepton-sensitive strains, NH2, was found to have the expected increase in length of the BamHI fragment from 2.8 to 3.7 kbp (Fig. 4B, lane 3). With respect to the morphological phenotypes on solid media, strain NH2 was identical to the wild-type strain, further confirming that the VB-BarA pathway does not participate in morphological control in S. virginiae.

Several phenotypes of strain NH2.

While the wild-type segregant and the wild-type parental strain produced virginiamycin in similar amounts, neither strain NH2 nor the plasmid-integrated strain produced virginiamycin (Table 1), indicating that this version of mutated barA was dominant over the wild-type barA and that the presence of the mutated barA caused the inhibition of virginiamycin production. Although the mutated BarA protein was scarcely visible in crude extracts of strain NH2 by anti-BarA antibody, probably due to the deletion of a major epitope in the mutated BarA (unpublished data), the dominant negative phenotype of strain NH2 suggested that sufficient mutated BarA should be present in the cell to allow complete repression of virginiamycin production, even in the presence of VB. The results of the VB binding assay revealed that strain NH2 was deficient in VB binding activity (Table 1), which may suggest that the C-terminal deletion of BarA severely impaired VB binding activity. In marked contrast to the virginiamycin production and VB binding activity, strain NH2 retained its ability to produce VB, while strain NH1 completely lost this ability (Table 1). Because the main difference between the two constructs in the two strains is that the intact helix-turn-helix motif is present in the former and absent in the latter, this motif of BarA can be considered important in the control of VB biosynthesis. Assuming that the major function of BarA is exerted by binding to specific DNA sequences in order to repress target genes in the absence of VB, as indicated from our previous in vitro study (12), VB biosynthesis seems to require an unidentified ene (gene X), the repression of which by intact BarA may be essential for VB biosynthesis. Alternatively, if BarA is assumed as a dual-function regulator acting both as a repressor and an activator, BarA may act as an activator for VB biosynthesis.

In this work, we presented the first in vivo evidence that BarA is an active regulatory component of the VB signal cascade that leads to virginiamycin production. In addition to its repressive function in virginiamycin production, BarA can be concluded to engage in the control of VB biosynthesis. Further investigation is under way in our laboratory to clarify the underlying mechanisms for the pleiotropic role of BarA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the Proposal-Based Advanced Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of Japan, by the Research for the Future Program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), and by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (BMP-97-V-4-1-b).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chater K F. Sporulation in Streptomyces. In: Smith I, Slepecky R A, Setlow P, editors. Regulation of prokaryotic development: structural and functional analysis of bacterial sporulation and germination. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 277–299. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denis F, Brzezinski R. An improved aminoglycoside resistance gene cassette for use in Gram-negative bacteria and Streptomyces. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;81:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gräfe U, Schade W, Eritt I, Fleck W F, Radics L. A new inducer of anthracycline biosynthesis from Streptomyces viridochromogenes. J Antibiot. 1982;35:1722–1723. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto K, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Distribution of virginiae butanolides and IM-2 in the genus Streptomyces. J Ferment Bioeng. 1992;73:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopwood D A. Towards an understanding of gene switching in Streptomyces, the basis of sporulation and antibiotic production. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1988;235:121–138. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Autoregulatory factors and communication in actinomycetes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:377–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawachi R, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Development of a transformation system in Streptomyces virginiae. Actinomycetologica. 1997;11:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H S, Nihira T, Tada H, Yanagimoto M, Yamada Y. Identification of binding protein of virginiae butanolide C, an autoregulator in virginiamycin production, from Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1989;42:769–778. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H S, Tada H, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Purification and characterization of virginiae butanolide C-binding protein, a possible pleiotropic signal-transducer in Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1990;43:692–706. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinoshita H, Ipposhi H, Okamoto S, Nakano H, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Butyrolactone autoregulator receptor protein (BarA) as a transcriptional regulator in Streptomyces virginiae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6986–6993. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.6986-6993.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleiner E M, Pliner S A, Soifer V S, Onoprienko V V, Blashova T A, Rosynov B V, Khokhlov A S. The structure of A-factor, a bioregulator from Streptomyces griseus. Bioorg Khim. 1976;2:1142–1147. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo K, Higuchi Y, Sakuda S, Nihira T, Yamada Y. New virginiae butanolides from Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1989;42:1873–1876. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C K, Minami M, Sakuda S, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Stereospecific reduction of virginiamycin M1 as the virginiamycin resistance pathway in Streptomyces virginiae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:595–601. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyake K, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M, Chiba N, Mori K, Nogawa N, Morikawa N, Beppu T. Detection and properties of A-factor-binding protein from Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4298–4302. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4298-4302.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizuno K, Sakuda S, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Enzymatic resolution of 2-acyl-3-hydroxymethyl-4-butanolide and preparation of optically active IM-2, the autoregulator from Streptomyces sp. FRI-5. Tetrahedron. 1996;50:10849–10858. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori K. Revision of the absolute configuration of A-factor. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:3107–3109. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muth G, Nußbaumer B, Wohlleben W, Pühler A. A vector system with temperature-sensitive replication for gene disruption and mutational cloning in streptomycetes. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:341–348. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nihira T, Shimizu Y, Kim H S, Yamada Y. Structure-activity relationships of virginiae butanolide C, an inducer of virginiamycin production in Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1988;41:1828–1837. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto S, Nakajima K, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Virginiae butanolide binding protein from Streptomyces virginiae. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12319–12326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakuda S, Yamada Y. Stereochemistry of butyrolactone autoregulators from Streptomyces. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:1817–1820. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato K, Nihira T, Sakuda S, Yanagimoto M, Yamada Y. Isolation and structure of a new butyrolactone autoregulator from Streptomyces sp. FRI-5. J Ferment Bioeng. 1989;68:170–173. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Nihira T, Sakuda S, Nishida T, Yamada Y. New inducing factors for virginiamycin production from Streptomyces antibioticus. J Ferment Bioeng. 1992;74:214–217. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward J M, Janssen G R, Kieser T, Bibb M J, Buttner M J, Bibb M J. Construction and characterisation of a series of multi-copy promoter-probe plasmid vectors for Streptomyces using the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene from Tn5 as indicator. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:468–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00422072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada Y, Nihira T, Sakuda S. Biosynthesis and receptor protein of butyrolactone autoregulator of Streptomyces virginiae. Actinomycetologica. 1992;6:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada Y, Sugamura K, Kondo K, Yanagimoto M, Okada H. The structure of inducing factors for virginiamycin production in Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1987;40:496–504. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanagimoto M. Novel actions of inducer in staphylomycin production by Streptomyces virginiae. J Ferment Technol. 1983;61:443–448. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanagimoto M, Enatsu T. Regulation of a blue pigment production by γ-nonalactone in Streptomyces sp. J Ferment Technol. 1983;61:545–550. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y K, Shimizu H, Shioya S, Suga K, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Optimum autoregulator addition strategy for maximum virginiamycin production in batch culture of Streptomyces virginiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;46:437–442. doi: 10.1002/bit.260460507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]