Abstract

Purpose

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in India. However, less than half receive treatment with a curative intent and very few undergo surgery amongst them. We present our surgical experience with non-small cell lung cancer.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of a cohort of 92 non-small cell lung cancer patients operated with curative intent.

Results

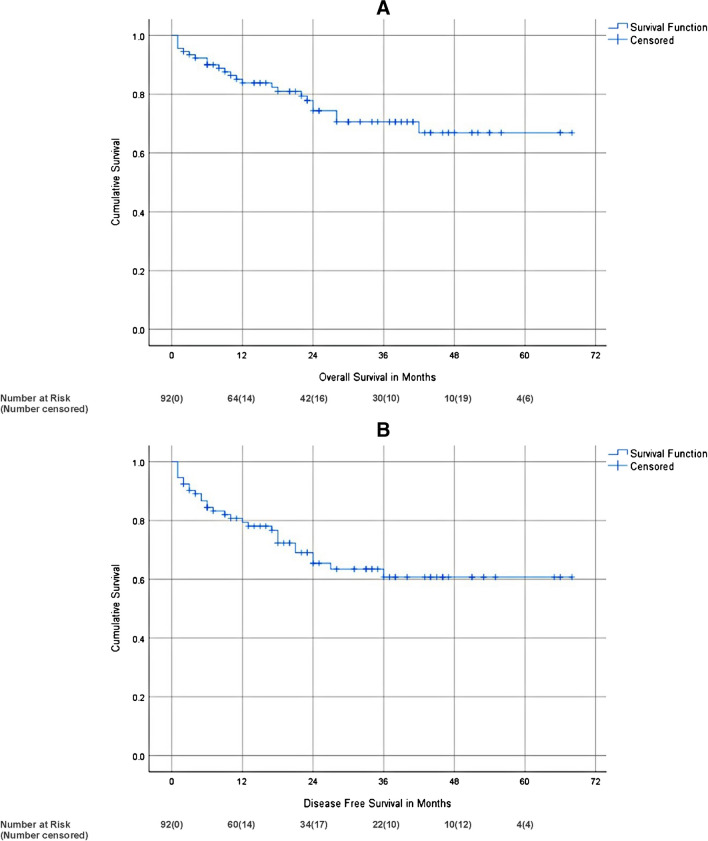

Less than 2% patients of lung cancer were operated on at our centre. Adenocarcinoma was the most common histological subtype. Right upper lobectomy was the most common surgery performed. Two- and 3-year overall survival was 74.3% and 70.6% respectively. Two- and 3- year disease-free survival was 65.4% and 60.8% respectively.

Conclusion

The fraction of patients who are operated for lung cancer is very less. There is a definite missed window of opportunity. We have comparable survival to international data.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Thoracic surgery

Introduction

Globally, lung cancer is the second most common cancer after breast cancer and is the most common cause of death due to cancer [1]. Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in Indian males along with oral cancer. It is diagnosed in a metastatic state in around 45% of patients in India [2]. However, only 31.7% receive curative treatment in India even in tertiary centres [3]. Of these, only 1.5 to 10% undergo surgery [3, 4]. In addition, the literature on the surgical treatment of lung cancer in India is sparse. We present our experience with lung cancer surgery.

Material and methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted in a tertiary, state cancer centre in Western India. After approval from the scientific review committee, patient data and follow-up were collected from the hospital database and telephonic communication.

Ninety-two patients who underwent surgery for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were included in this study. Patients were diagnosed by either computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy or bronchoscopic biopsy. All patients underwent staging with a positron emission tomography CT scan. Invasive mediastinal staging was not done for any patient. Post-neoadjuvant therapy re-evaluation was done with a CT scan of the thorax and upper abdomen.

Inclusion criteria included patients with non-small cell carcinoma of the lung who underwent curative surgery at our centre between January 2017 and June 2021. Patients were followed up until August 2022 (Fig. 1). Patients who were inoperable, had a histology other than NSCLC on final histopathology, or had a dual malignancy were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Patient selection flow chart

All patients were advised to stop smoking on their first visit to the outpatient department. We routinely waited for at least 4 weeks post-cessation of smoking before surgery, but each case was tackled individually. Surgical procedures were performed either by an open or a minimally invasive surgical approach. Curative surgery was considered for T1, T2, peripheral and central T3, and peripheral T4 lesions, where a margin could be obtained. Patients with N1 and discrete N2 nodal status were also considered for surgery. Patients were given neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy as per discussion in the institutional tumour board. Follow-up was 3 monthly for the first 2 years and 6 monthly for the next 3 years. A complete history and physical examination were done on each follow-up. A contrast-enhanced CT scan was done 6 monthly for the first 2 years on follow-up and then annually.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the use of IBM SPSS software, version 25.0 (SPSS). Average and frequency distribution were analysed by descriptive statistics. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyse survival. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of histological diagnosis to the date of death and censored at last follow-up. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of relapse or death and censored at the last follow-up. Log-rank test was used for univariate analysis and multivariate analysis was done by Cox proportional hazards regression. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and demographic data

The median age of the patients was 60 years (range 21 to 72) and 78 (84.78%) were male. The most common presenting symptoms were chest pain and cough which occurred in more than half of the patients (60 (65.2%) and 52 (56.5%) respectively). Twenty-three (25%) patients had dyspnea and 12 (13%) had haemoptysis. Generalised weakness, weight loss and anorexia were complained of by 15 (16.3%) patients. Four patients had fever and one had Cushingoid features. Fifty-two (56.5%) patients complained of more than one symptom and 36 (39.1%) had only one symptom. Four patients were diagnosed incidentally by imaging done for routine health check-up done elsewhere.

On enquiring about addictions, 68 (74%) patients had a history of smoking tobacco. Of those, 46 (50%) patients consumed bidi (type of smoked tobacco) and 22 (24%) were cigarette smokers. Seven (7.6%) chewed tobacco and 17 (18.4%) had no addictions. Of those who smoked, 22 (24%) patients had a history of consumption of more than 30 pack-years.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) was given to 14 (16.4%) patients (excluding neuroendocrine tumours (NETs)) as they were all typical carcinoids. Platinum doublet-based therapy, which included pemetrexed, paclitaxel or gemcitabine, and cisplatin, was given as per histology and performance status. All patients who were given NACT were either down-staged or remained stable on imaging after NACT.

Surgical data

A right lung tumour was the most common (n = 54; 58.6% of patients). The most common surgery was a right upper lobectomy (n = 27; 29.3%) (Table 1). Three patients underwent sub-lobar resections. Of them, 2 patients underwent wedge resection. The first was for a patient with poor performance status having a peripheral NET with Cushingoid features. The second wedge resection was for a patient with a peripheral stage 1 lesion who was not maintaining saturation intraoperatively. Segmentectomy was done for a patient with a peripheral lesion and severe restrictive lung disease. All 3 had R0 resection.

Table 1.

Type of surgery

| Surgery | Number |

|---|---|

| Right upper lobectomy | 27 (29.3%) |

| Right middle lobectomy | 3 (3.26%) |

| Right lower lobectomy | 6 (6.52%) |

| Right upper + middle lobectomy | 7 (7.6%) |

| Right middle + lower lobectomy | 7 (7.6%) |

| Right pneumonectomy | 4 (4.3%) |

| Left upper lobectomy | 12 (13%) |

| Left lower lobectomy | 19 (20.6%) |

| Left pneumonectomy | 4 (4.3%) |

| Left apico-posterior segmentectomy | 1 (1%) |

| Wedge resection | 2 (2.1%) |

A majority (n = 56; 60.8%) of patients underwent open surgery. Twenty-six (28.2%) patients were started with a thoracoscopic approach but were converted to open surgery and the remaining 10 (10.8%) underwent complete thoracoscopic surgery. Rib excision was required in 20 (21.7%) patients, of which 60% required the removal of more than 2 ribs. Of those requiring excision of more than 2 ribs, there were 4 cases each of stages 2, 3A and 3B.

Ribs were resected for involvement, or for an adequate margin. Involvement was either gross involvement or also for cases where the tumour was densely adherent to the periosteum of the rib or the pleura and the rib was resected to obtain an R0 margin. The defect was reconstructed with a polypropylene mesh in cases where more than 2 ribs were excised.

Postoperative morbidity and mortality

Postoperative morbidity was seen in 22 (23.9%), out of which 4 (4.35%) expired (Table 2). Alveolar air leak was the commonest complication which was managed by prolonged negative suction intercostal drainage. Collapse-consolidation occurred in 6 patients. It was managed with deep breathing, chest physiotherapy and bronchoscopic lavage as needed. One patient with collapse-consolidation, who developed severe sepsis, expired. Four patients developed a bronchopleural fistula. Three were following an upper lobectomy and one followed a bi-lobectomy (middle and lower). Three followed upfront surgery and one followed neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Margins were free in all 4 cases. All 4 patients were re-explored. One was managed with the placement of a serratus flap while the other three underwent a pneumonectomy. All 4 are alive and on follow-up.

Table 2.

Postoperative complications

| Clavien-Dindo classification degree (n) [5] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication (n) | 1 (2) | 2 (10) | 3A (1) | 3B (4) | 4A (1) | 4B (0) | 5 (4) |

| Alveolar air leak (7) | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lung collapse-consolidation (6) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bronchopleural fistula (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bleeding (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Phrenic nerve palsy (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrent nerve palsy (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ARDS (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Two patients developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) following prolonged postoperative ventilation along with multiorgan failure. Both succumbed. One patient expired following a sudden massive haemorrhage before the patient could be re-explored.

Pathological data

R0 resection was achieved in 88 (95.65%) of the patients.

There was a preponderance of 55 (59.8%) patients with adenocarcinoma and 22 (23.9%) were squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Lymphadenectomy was done in 91 patients. The median yield of lymph nodes was 10 (inter-quartile range was 5 to 17). A comparison of clinical and pathological staging is given in Tables 3 and 4. Out of the 78 patients operated upfront, only 52 had a pathological stage corresponding to the clinical stage. Eighteen were up-staged, and eight were down-staged by one stage.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical versus pathological staging for patients operated upfront

| pT1 (14) | pT2 (25) | pT3 (30) | pT4 (9) | Nx | pN0 (53) | pN1 (16) | pN2 (8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cT1 (16) | 10 | 5 | 1 | 0 | cN0 (49) | 1 | 43 | 4 | 1 |

| cT2 (19) | 4 | 11 | 4 | 0 | cN1 (13) | 0 | 5 | 8 | 0 |

| cT3 (38) | 0 | 9 | 23 | 6 | cN2 (16) | 0 | 5 | 4 | 7 |

| cT4 (5) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |||||

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical versus pathological staging for patients operated post-NACT

| ypT0 (2) | ypT1 (0) | ypT2 (5) | ypT3 (7) | ypN0 (8) | ypN1 (3) | ypN2 (3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cT1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | cN0 (4) | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| cT2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | cN1 (5) | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| cT3 (9) | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 | cN2 (5) | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| cT4 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | ||||

A total of 14 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. On final pathology, 9 of them were down-staged, including 1 with a pathological complete response. Four patients had no change in final pathology compared to their initial clinical stage and one progressed.

Forty-two patients received adjuvant therapy. Adjuvant chemoradiation was given to 14 (15.2%) and 28 (30.4%) received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Survival data

The median follow-up time of alive patients was 30 months (range 2 to 68 months; inter-quartile range 16 to 43). Two- and 3-year OS was 74.3% and 70.6% respectively. Two- and 3-year DFS was 65.4% and 60.8% respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve of overall (A) and disease-free (B) survival

Of the various factors analysed affecting survival on univariate analysis, smoking, histology and stage were the factors affecting overall survival. Stage, lympho-vascular invasion and peri-neural invasion were the factors affecting DFS (Table 5). However, on multivariate analysis, no factors significantly affected DFS or OS (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of factors affecting overall survival and disease-free survival

| Characteristic | Variable | Frequency | 2-year DFS (%) | p value | 2-year OS (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 60 | 44 (47.82%) | 68.7 | 0.31 | 81.5 | 0.10 |

| > 60 | 48 (52.18%) | 62.0 | 67.2 | |||

| Gender | Male | 78 (84.78%) | 63.8 | 0.21 | 90.9 | 0.07 |

| Female | 14 (15.21%) | 75.7 | 71.7 | |||

| Smoking | > 30 pack-years | 22 (24%) | 83.6 | 0.98 | 51.3 | 0.01 |

| < 30 pack-years | 46 (50%) | 84 | 75.3 | |||

| Non-smokers | 24 (26%) | 81 | 91.5 | |||

| Pre-operative albumin (g/dl) | < 3.5 | 22 (23.91%) | 60 | 0.87 | 73.1 | 0.97 |

| > 3.5 | 70 (76.08%) | 67.5 | 74.8 | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapya | No | 71 (83.52%) | 65.1 | 0.57 | 73.7 | 0.49 |

| Yes | 14 (16.48%) | 69.3 | 84.4 | |||

| Histological differentiation | Adenocarcinoma | 55 (59.78%) | 68.9 | 0.11 | 76.6 | 0.02 |

| Squamous cell cancer | 22 (23.91%) | 44.4 | 58.3 | |||

| Large cell | 4 (4.34%) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Neuroendocrine tumours (NET) | 7 (7.60%) | 100 | 100 | |||

| Others | 4 (4.34%) | 75 | 100 | |||

| Lympho-vascular invasion | Yes | 39 (42.39%) | 51.7 | 0.02 | 66.5 | 0.15 |

| No | 53 (57.60%) | 75.2 | 82.8 | |||

| Peri-neural invasion | Yes | 7 (7.60%) | 17.1 | 0.005 | 66.7 | 0.61 |

| No | 85 (92.39%) | 73.2 | 75.2 | |||

| Margin | R0 | 88 (95.65%) | 67.8 | 0.10 | 76.1 | 0.21 |

| R1 | 4 (4.35%) | 25 | 37.5 | |||

| Stageb | 1 | 18 (19.56%) | 71.8 | 0.02 | 88.5 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 42 (45.65%) | 74.5 | 83.5 | |||

| 3A | 23 (25%) | 57.5 | 65.1 | |||

| 3B | 9 (9.78%) | 29.6 | 35.6 |

Bold signifies that the value is significant (p less than 0.5)

aSeven patients with NET histology were excluded from evaluation on NACT as they were all typical carcinoids in which there is no role for NACT

bUpfront operated patients were staged as per final histopathology and patients who underwent neoadjuvant treatment were staged as per initial clinical staging

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis of significant factors affecting OS

| Characteristic | Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | 1 | |||

| 2 | 1.24 | 0.31 to 4.99 | 0.75 | |

| 3A | 1.35 | 0.27 to 6.56 | 0.70 | |

| 3B | 3.69 | 0.67 to 20.16 | 0.13 | |

| Smoking | No | |||

| < 30 pack-years | 1.01 | 0.26 to 3.92 | 0.98 | |

| > 30 pack-years | 3.43 | 0.89 to 13.20 | 0.07 | |

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma | |||

| Large cell | 4.70 | 0.78 to 28.35 | 0.09 | |

| NETa | 0.00 | 0 to infinity | 0.98 | |

| Othera | 0.00 | 0 to infinity | 0.98 | |

| Squamous cell cancer | 1.96 | 0.68 to 5.64 | 0.20 | |

aHazard ratio is zero as survival is 100%

Table 7.

Multivariate analysis of significant factors affecting DFS

| Characteristic | Variable | Hazard ratio | Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | 1 | |||

| 2 | 1.21 | 0.31 to 4.61 | 0.77 | |

| 3A | 0.62 | 0.11 to 3.49 | 0.59 | |

| 3B | 2.17 | 0.35 to 13.49 | 0.40 | |

| LVI | Negative | |||

| Positive | 1.04 | 0.27 to 4.05 | 0.9 | |

| PNI | Negative | |||

| Positive | 4.65 | 0.52 to 2.83 | 0.12 | |

Discussion

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database estimated the incidence of lung cancer in 2022 and found that lung cancer accounts for 12.3% of all new cases [6].

The median age at diagnosis in our study was 60 years, which is 10 years earlier than that published by the American Cancer Society [7]. This leads to greater years of life lost in the Indian population due to lung cancer.

Lung cancer is more common in males with a rate of 589/1 million persons in males and 468/1 million persons in females. In the present study, 84.78% of the total patients recruited were males. Similarly, a study from Northern India on lung cancers also had 82.9% male patients [8].

Seventy-four percent of the patients in our study were smokers, with around one-third of those having a pack history of more than 30 years. This corresponds to the study in Northern India by Kumar et al. but is much higher than the 53% reported in the study by Murali et al. from Southern India [9, 10].

Chest pain and cough were the presenting symptoms in more than half of the cases in our study with dyspnea occurring in one-fourth and haemoptysis in twelve. Murali and colleagues reported cough to be the most common symptom in their study; however, they have reported on lung cancers in general and not on those undergoing surgery in particular [10]. Cough followed by loss of appetite and dyspnea were the most common symptoms in the study in Northern India [9].

The most common type of NSCLC is adenocarcinoma, which accounts for 40% of lung cancer cases [11]. In the present study, the most common histological type was adenocarcinoma, which accounts for 59.8% of the patients. This is consistent with the shift from earlier predominance of SCC. Adenocarcinoma also has a better OS than SCC in our study.

NACT is considered in T3 or T4 patients to improve operability, when close to vital structures, or in N2 disease. Sixteen percent of our patients underwent NACT prior to surgery in comparison with around one-third in a study from Northern India [9].

American Lung Association published that 20.6% of total lung cancer patients underwent curative surgery [12]. In the present study, less than 2% of the total patients presenting to our hospital underwent curative surgery. A study from All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, also had only 3% of their patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer [9]. Another study by Murali et al. from Chennai had 5.19% of patients undergoing surgery [10]. This shows that we have lost the window of opportunity for many patients. Yue et al. published survival data of NSCLC patients and found that the surgery improves OS significantly [13].

Given that surgery is part of the treatment for lung cancer up to stage 3A/B, it shows a gross underutilisation of surgery and hence the chance for cure in a large portion of patients.

The majority of surgeries were done via the open method at our institution or converted to open from a thoracoscopic approach. However, the percentage of conversion decreased as more cases were operated. Insertion of a scope helps to detect metastatic disease prior to a thoracotomy, helps in planning the incision especially when rib excision is required and also helps in lysis of adhesions.

Deslauriers reported postoperative morbidity of 27% and mortality of 3.7%, whereas Duque et al. had 32.4% morbidity and 6.6% mortality [14, 15]. We had a 19.5% postoperative morbidity and 4.35% postoperative mortality. The most common postoperative complications of lung cancer surgeries are pneumonia in 2–20% of cases, bronchopleural fistula in 2–13% of cases and persistent air leak in 3–8% of cases [16]. In the present study, alveolar air leak was the most frequent complication. Respiratory complications were observed only in patients with a smoking history.

Bronchopleural fistula is a dreaded complication. We do not reinforce the bronchial stump with a flap at our centre. A best evidence review suggested that there is a benefit to buttressing the stump post pneumonectomy in diabetic patients. Flap coverage in other high-risk situations has been reported in case series. A pedicled intercostal flap appears to be the best method for the same [17]. A recent retrospective review of 558 patients did not show a benefit of flap coverage following either lobectomy or pneumonectomy [18]. A meta-analysis on coverage post pneumonectomy of the bronchial stump suggested that there is no benefit for coverage but that a proper randomised trial is necessary to confirm the same [19].

The present study showed 2-year and 3-year OS of 74.3% and 70.6% respectively. The 2-year and 3-year DFS was 65.4% and 60.8% respectively. Stages 1 and 2, no smoking and NET or adenocarcinoma histology were associated with better overall survival. Earlier stage, no lympho-vascular or peri-neural invasion was associated with better DFS. However, on multivariate analysis, none of the factors affected either DFS or OS. In past papers, stage at the time of surgery is an accurate predictor of long-term survival [20]. In a recent study from Turkey, a low postoperative percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s (ppFEV1) value was associated with lower postoperative survival [21]. SEER database published a survival analysis of 2011–2017 data and the 5-year relative survival rate of NSCLC with localised, regional, and distant disease and the overall survival was 64%, 37%, 6%, and 26% respectively [22]. The present study showed that 3-year survival of stages I, II, IIIA and IIIB was 82.2%, 75.9%, 65.1% and 35.6% respectively. A recent study from Taiwan showed 3-year overall survival of all types of lung cancer for stages I, II and III as 89.9%, 59.92% and 37.01% respectively [23]. We have comparable OS.

There are not many studies available in India regarding only survival analysis of patients who had undergone curative resections. The merits of the present study were the long follow-up duration, prognostic factor analysis, and the tertiary centre study.

Limitations

The limitations of the study were a single institutional study, small sample size and it is a retrospective study.

Conclusion

The fraction of patients who were operated for lung cancer was very small indicating a missed window of opportunity. Better screening protocols may help address the same. The most common histological subtype was adenocarcinoma. Complications such as bronchopleural fistula and collapse-consolidation require timely intervention for a better outcome. Survival in our study was comparable to published Western literature. Advanced stage at diagnosis, a history of smoking and squamous and large cell histology were associated with poorer OS. Presence of lympho-vascular invasion, peri-neural invasion and advanced stage at diagnosis were associated with poorer DFS.

Funding

None.

Data Availability

Data is available internally to all staff of the parent institute. For external researchers, ethical approval may be obtained to view the data. Interested parties are advised to contact the corresponding author to discuss the application for the same.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Approval was taken from the Institutional Review Committee prior to accessing the data.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients regarding publishing data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Statement of animal and human rights

There was no infringement of human or animal rights in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries - Sung - 2021 - CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mathur P, Sathishkumar K, Chaturvedi M, Das P, Sudarshan KL, Santhappan S, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2020: report from National Cancer Registry Programme, India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1063–1075. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh N, Agrawal S, Jiwnani S, Khosla D, Malik PS, Mohan A, et al. Lung cancer in India. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:1250–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apurva A, Tandon S, Shetmahajan M, Jiwnani S, Karimundackal G, Pramesh C. Surgery for lung cancer—the Indian scenario. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;34:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12055-017-0634-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancer of the lung and bronchus - cancer stat facts [Internet]. SEER. [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html.

- 7.Lung Cancer Statistics | How common is lung cancer? [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- 8.Mohan A, Garg A, Gupta A, Sahu S, Choudhari C, Vashistha V, et al. Clinical profile of lung cancer in North India: a 10-year analysis of 1862 patients from a tertiary care center. Lung India. 2020;37:190–197. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_333_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S, Saikia J, Kumar V, Malik PS, Madan K, Jain D, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery in lung cancer: Indian scenario. Curr Probl Cancer. 2020;44:100563. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2020.100563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murali AN, Radhakrishnan V, Ganesan TS, Rajendranath R, Ganesan P, Selvaluxmy G, et al. Outcomes in lung cancer: 9-year experience from a tertiary cancer center in India. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3:459–468. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers DJ, Wallen JM. Lung Adenocarcinoma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519578.

- 12.1. [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 9]. Available from: https://www.lung.org/getmedia/381ca407-a4e9-4069-b24b-195811f29a00/solc-2020-report-final.pdf.

- 13.Yue D, Gong L, You J, Su Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, et al. Survival analysis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer who underwent surgical resection following 4 lung cancer resection guidelines. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:422. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deslauriers J, Ginsberg RJ, Piantadosi S, Fournier B. Prospective assessment of 30-day operative morbidity for surgical resections in lung cancer. Chest. 1994;106:329S–330S. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6_Supplement.329S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duque JL, Ramos G, Castrodeza J, Cerezal J, Castanedo M, Yuste MG, et al. Early complications in surgical treatment of lung cancer: a prospective, multicenter study. Grupo Cooperativo de Carcinoma Broncogénico de la Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:944–50. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burel J, El Ayoubi M, Baste JM, Garnier M, Montagne F, Dacher JN, et al. Surgery for lung cancer: postoperative changes and complications—what the radiologist needs to know. Insights Imaging. 2021;12:116. doi: 10.1186/s13244-021-01047-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llewellyn-Bennett R, Wotton R, West D. Prophylactic flap coverage and the incidence of bronchopleural fistulae after pneumonectomy [Internet]. U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2013 [cited 2023 May 9]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3630421/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Caushi F, Qirjako G, Skenduli I, Xhemalaj D, Hafizi H, Bala S, et al. Is the flap reinforcement of the bronchial stump really necessary to prevent bronchial fistula? - journal of cardiothoracic surgery [Internet]. BioMed Central; 2020 [cited 2023 May 9]. 10.1186/s13019-020-01290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Di Maio M;Perrone F;Deschamps C;Rocco G; A meta-analysis of the impact of bronchial stump coverage on the risk of bronchopleural fistula after pneumonectomy [Internet]. U.S. National Library of Medicine; [cited 2023 May 9]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25342849/#:~:text=The%20occurrence%20of%20bronchopleural%20fistula,cancer%20surgery%20or%20benign%20disease. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.al-Kattan K, Sepsas E, Townsend ER, Fountain SW. Factors affecting long term survival following resection for lung cancer. Thorax. 1996;51:1266–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.12.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sezen CB, Gokce A, Kalafat CE, Aker C, Tastepe AI. Risk factors for postoperative complications and long-term survival in elderly lung cancer patients: a single institutional experience in Turkey. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;67:442–449. doi: 10.1007/s11748-018-1031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lung Cancer Survival Rates | 5-year survival rates for lung cancer [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html.

- 23.Tsai HC, Huang JY, Hsieh MY, Wang BY. Survival of lung cancer patients by histopathology in Taiwan from 2010 to 2016: a nationwide study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:5503. doi: 10.3390/jcm11195503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available internally to all staff of the parent institute. For external researchers, ethical approval may be obtained to view the data. Interested parties are advised to contact the corresponding author to discuss the application for the same.